Abstract

Achieving fisheries compliance is challenging in contexts where enforcement capacity is limited and the incentives for rule-breaking are strong. This challenge is exemplified in Myanmar, where an active shark fishery exists despite a nationwide ban on targeted shark fishing. We used the Kipling method (5W1H) to gather a complete story of non-compliance in five small-scale fishing communities in the Myeik Archipelago. Among 144 fishers surveyed, 49% were aware of the nationwide ban. Shark fishers (24%) tended to be younger individuals who did not own a boat and perceived shark fishing to be prevalent. Compliant fishers were motivated by a fear of sharks and lack of capacity (equipment, knowledge), whereas food and income were cited as key motivations for non-compliance. The results of our study emphasize that in resource-dependent communities, improving compliance for effective shark conservation may require addressing broader issues of poverty, food security and the lack of alternatives.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-020-01400-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Compliance, Livelihoods, Shark conservation, Shark fishing, Small-scale fisheries

Introduction

Compliance with rules and regulations is critical for effective natural resource management and conservation (Arias 2015), yet non-compliance is widespread, and regularly undermines the achievement of positive ecological outcomes in terrestrial and marine ecosystems (Mora et al. 2006). In marine contexts, even short bursts of illegal fishing can rapidly negate the effect of decades of protection (e.g. Russ and Alcala 2010). This is particularly the case where protection is focused on species such as sharks—here, defined as the elasmobranch superorder Selachii—many of which are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation due to their slow growth, late maturity, and low fecundity (Cortes 2002).

Overfishing has driven widespread population declines of many shark species (Dulvy et al. 2014). In an effort to combat these declines, a number of global initiatives have attempted to improve the conservation and sustainable management of sharks. For example, in 1999 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization recommended that shark fishing nations adopt and implement National Plans of Action for Sharks as a commitment to the goal of “ensuring the conservation and management of sharks and their long-term sustainable use” (UN FAO 2013). Other global initiatives have included the application of trade regulations through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) (Vincent et al. 2014; Friedman et al. 2018), and the establishment of the Convention of Migratory Species Memorandum of Understanding for Sharks (Fowler 2012). The wide variety of measures have been implemented with varying levels of success (Davidson et al. 2016; Dulvy et al. 2017).

An increasingly popular approach to improving shark population outcomes is to reduce shark mortality through the establishment of marine protected areas and ‘Shark Sanctuaries’. To date, 17 countries have implemented Shark Sanctuaries which ban targeted fishing for sharks in national waters (Ward-Paige 2017; Ward-Paige and Worm 2017; Pew Charitable Trusts 2018); others have created marine protected areas where shark conservation is an explicit goal (Dulvy 2013). While specific approaches restrict fishing in different ways, they are similar in that their success is largely dependent on compliance with regulations.

Understanding the motivations and characteristics of rule-breakers can facilitate the development of targeted strategies to increase compliance (Keane et al. 2008; St. John et al. 2010; Travers et al. 2019). In contexts where the capacity for enforcement is limited and the incentive for rule-breaking is strong, approaches to improve voluntary compliance may be particularly useful (Battista et al. 2018). To date, however, research on the behavioural drivers of illegal fishing has focused largely on recreational fishers in higher-income country contexts (e.g. Bova et al. 2017; Bergseth and Roscher 2018). Meanwhile, approximately 97% of the world’s fishers live in lower-income countries, of which 90% are engaged in the small-scale fisheries sector (World Bank et al. 2012). The few studies that have explored fisheries non-compliance in lower-income countries (e.g. Carr et al. 2013; Cepić and Nunan 2017) have not investigated the relationship between various behavioural drivers (e.g. norms, legitimacy) and individual non-compliance. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the first in-depth study to explore both the levels and potential behavioural drivers of illegal shark fishing in a lower-income country context.

This paper aims to explore illegal shark fishing by small-scale fishers, using Myanmar’s Myeik Archipelago as a case study. Despite a nationwide ban on targeted shark fishing (hereafter ‘shark fishing’), sharks are actively caught and sold by small-scale fishers throughout the archipelago (Howard et al. 2015). Enforcement of the shark fishing ban is severely constrained by a lack of capacity—the Department of Fisheries lacks patrol vessels, and the Navy’s on-water patrols are focused on illegal fishing by foreign vessels (BOBLME 2015a). This lack of enforcement capacity, combined with high fishing pressure, destructive fishing practices and high market demand for shark products, have contributed to severe declines in shark populations throughout the archipelago (Krakstad et al. 2014; Howard et al. 2015).

Here, we investigate fishers’ awareness of, compliance with, and perceptions towards shark fishing regulations, with the aim of informing strategies to increase compliance. Using the Kipling method (5W1H) to gather a complete picture of compliance, we describe the behaviour by asking: who complies (or not)? What species are caught (and how)? Where and when are sharks targeted, and where is the catch sold? We then attempt to explain the behaviour by asking: why do fishers comply (or not)? To address this last question, we apply models of human behaviour using a theoretical framework outlined in the following section.

Theoretical Framework

Our study draws on theoretical and empirical literature on human behaviour to examine the potential behavioural drivers of non-compliance. Specifically, we draw on the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991) and research in social psychology and law to examine the factors related to self-reported shark fishing.

The theory of planned behaviour is widely applied in social psychology to predict a range of behaviours by examining cognitive decision-making processes (St John et al. 2010). The theory suggests that an individual’s intention and motivation towards a given behaviour is shaped by their attitudes, subjective norms (i.e. perceived social acceptability), and perceived behavioural control—that is, how easy or difficult the behaviour is to perform (Ajzen 1991). However, reviews of the theory have suggested that it be expanded to include additional cognitive and context-specific drivers of the behaviour in question (e.g. Armitage and Conner 2001). As such, we include additional indicators reflecting norms and attitudes that can influence behaviour—specifically, individual perceptions regarding (i) what is personally acceptable (personal norms); (ii) what other people do (descriptive norms, or perceived level of non-compliance); (iii) whether the rule is superfluous (i.e. if shark fishing has no effect on shark populations); and (iv) the legitimacy of the rule and rule-makers (Kuperan and Sutinen 1998; Cialdini 2007; Levi et al. 2009; White et al. 2009; Cepić and Nunan 2017).

Research in social psychology and law has explored the link between compliance and the perceived legitimacy of regulations and governing authorities (e.g. Kuperan and Sutinen 1998, Levi et al. 2009). Perceptions of legitimacy can in turn be shaped by whether people (i) consider others to be well informed about the rule; (ii) support the rule (Turner et al. 2016); (iii) feel involved in decision-making (Pollnac et al. 2010; Arias et al. 2015); (iv) view enforcement activities to be effective; and (v) consider the rule itself to be effective in achieving the desired outcome (e.g. stock replenishment; Sutinen and Kuperan 1999). We thus used these five indicators to construct a single metric of legitimacy and examine its relationship with individual (self-reported) behaviour.

Materials and methods

Study context

Myanmar’s shark legislation

Myanmar’s shark fishing regulations are outlined in two pieces of legislation. The first, enacted in 2001, prohibits the capture and sale of whale sharks (BOBLME et al. 2015b). The second, enacted in 2004, outlines two shark reserves within the Myeik Archipelago (BOBLME et al. 2015b), a collection of approximately 800 islands distributed along 600 km of the Tanintharyi coast in the southernmost region of Myanmar. While the reserves prohibit the targeted capture of sharks (i.e. shark fishing) within their boundaries, few fishers are aware of their existence and the lack of enforcement capacity within the Department of Fisheries means that the reserves are essentially paper parks (Howard et al. 2015). The shark reserves were made redundant in 2009 when the Department of Fisheries declared a nationwide ban on shark fishing. The ban states that it is “illegal to catch, kill, disturb, transport, sell or keep any shark species” (BOBLME et al. 2015b, p. 19), however it remains a declaration as it was never formalised into legislation (BOBLME et al. 2015a). There is also some ambiguity regarding the details of the ban—for example, the declaration makes no specific mention regarding the capture and subsequent sale of sharks caught as bycatch (BOBLME et al. 2015b). Despite the lack of formal legislation, fishers, buyers and traders who are aware of the ban consider shark fishing to be against the law (Howard et al. 2015). However, the retention and subsequent sale of sharks caught as bycatch—or reported as such—appears to be legal (or is tolerated by authorities), as evidenced by the large quantities of shark meat and fins reported and sold as bycatch at markets along the coast (BOBLME et al. 2015b).

The Myeik Archipelago

The Myeik Archipelago is considered a Key Biodiversity Area of global importance (WCS 2013), and has been nominated as a “Natural” UNESCO site for its unique biodiversity and habitats (WHC 2014). To address threats of overfishing, a marine protected area network has been proposed for the area (Dearden 2016). Further, with the recent opening of Myanmar’s borders following decades of strict military rule and geopolitical isolation, the archipelago has become an increasingly popular tourism destination (MOHT 2013).

Of the estimated 58 shark species recorded in Myanmar’s waters, 24 have been recorded as target or incidental catch in the archipelago, including the threatened scalloped (Sphyrna lewini) and great (S. mokarran) hammerhead (Howard et al. 2015). In the Myeik Archipelago, trends in shark sightings and catches are declining, as reported by fishers during recent socio-economic surveys (Schneider et al. 2014). This perception is consistent with the low numbers of shark sightings in reports from scientific dive surveys (Howard et al. 2014, 2015) and dive tourism staff (Holmes et al. 2013).

While baseline socio-economic data is lacking for most of the archipelago, surveys conducted to date suggest that communities have low levels of livelihood diversification and are highly dependent on marine resources, with fishing recognized as the main livelihood activity (Instituto Oikos and BANCA 2011; Saw Han Shein et al. 2013; Schneider et al. 2014; MOECAF and Oikos 2015). Both mainland and island communities operate in a context of poverty, with inadequate access to clean water, sanitation, electricity, education, health facilities, and infrastructure (Nang Mya Han 2010; Instituto Oikos and BANCA 2011). Ongoing in-migration from the mainland has placed additional pressure on marine resources, with many migrating to islands to escape conflict, search for land and resources, and pursue better economic prospects (BOBLME 2015c).

Sampling

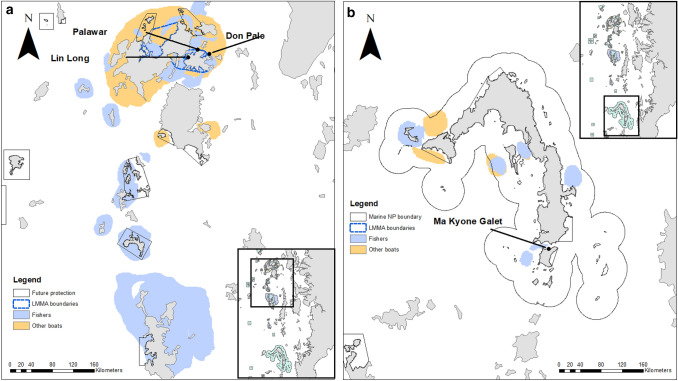

We studied five coastal communities across three locations in the Myeik Archipelago (Fig. 1) in November and December 2017. Communities were selected primarily because they have well-established relationships with local partners (Fauna and Flora International, Instituto Oikos, Myeik University), and because shark fishing is known to occur in the region (Howard et al. 2015). The mainland community of Myeik—located on the Tanintharyi coast—was added to our study following reports of large quantities of shark products being sold at wet and dry markets (Howard et al. 2015).

Fig. 1.

Map of the Myeik Archipelago, Myanmar, showing a Myanmar in a regional context; b location of study sites on Thayawthadangyi Island (Palawar, n = 11; Don Pale, n =39; Lin Long, n = 43); as well as study sites on Lampi Island (Makyone Galet, n = 31) and the mainland (Myeik, n = 20). Dashed blue lines indicate location of Shark Reserves

We used an opportunistic sampling methodology to maximize the number of respondents per community, with the sample size in a given community dependent on available time and population size. Our response rate was very high (approximately 95%), so we did not systematically record the response rate because refusals were so rare. All respondents gave informed consent to participate in the research. Our sampling protocol was reviewed and approved by James Cook University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (H7150). Permission to conduct research in Myanmar was provided by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation.

Survey methodology and data collection

We used household surveys to gather information on fishers’ awareness of, compliance with, and perceptions towards shark fishing regulations. We defined fishers as individuals who engaged in fishing activities, and non-compliant fishers as those who reported targeting sharks (hereafter, ‘shark fishers’). The semi-structured survey was designed to capture as much information as possible that was useful for understanding fishers’ reasons for engaging in shark fishing (Appendix S1). Given Myanmar’s history of strict military rule and the inherent challenges of asking questions about an illegal activity, we took extra care in designing the survey to reduce overall sensitivity and bias using forgiving wording and by placing more sensitive questions towards the end of the survey (Tourangeau and Yan 2007).

To understand who complies or not and construct a ‘profile of a shark fisher’, we collected information on fisher characteristics including age, education level, material style of life (Table S1), boat ownership, occupational multiplicity, migrant status, and awareness of shark fishing regulations (Table 1). We used participatory mapping to gather information regarding what shark families are caught, how (i.e. with what gears), when, and where. Fishers were given the opportunity to voluntarily identify whether, where, and when they (1) had personally caught sharks (either as target or incidental catch); and (2) had witnessed other boats catching sharks. Where sites identified by fishers did not fall within the map’s boundaries, the local name of the area was noted and later situated on a map.

Table 1.

Descriptions of dependent variable (shark fishing) and independent variables (fisher characteristics and perceptions) used in our model to construct profile of a shark fisher

| Variable | Description | Data type |

|---|---|---|

| Shark fishing | Whether the respondent reported targeting sharks (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

| Age | Age in number of years | Continuous |

| Education | Number of years of formal education | Continuous |

| Material style of life | Principal component score based on the type of wall, floor, and roof, and whether the home had electricity (Table S1) | Continuous |

| Boat owner | Whether the respondent owned a boat (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

| Occupational multiplicity | Total number of occupations in the household | Continuous |

| Migrant | Whether the respondent was born in the community (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

| Awareness | Whether the respondent was aware of any shark fishing laws (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

Given the limited awareness of the shark reserves and ambiguity surrounding the nationwide ban, we expected that some fishers in our study communities might not be aware of any shark fishing regulations. To avoid influencing fishers’ responses, shark reserve boundaries were not demarcated on the map, and we assessed fishers’ awareness of shark fishing regulations after the mapping exercise. We assessed awareness of shark fishing regulations by asking fishers whether they were aware of any rules or laws regarding shark fishing after and, if so, which laws they were aware of.

We used two approaches to explore why fishers comply (or not). First, to understand both individual and perceived motivations for (non)compliance, we asked fishers to provide two reasons why they target sharks (shark fishers) or not (compliant fishers)—referred to as ‘individual motivations’—and two reasons why they think others would target sharks or not (‘perceived motivations’). Second, we focused on fishers who were aware of the shark fishing legislation to examine whether fishers’ behaviour was related to: (i) having witnessed shark fishing; (ii) the perceived level of shark fishing in the community (‘perceived non-compliance’); (iii) the perceived effects of shark fishing on shark populations (to assess perceived superfluousness of the ban); (iv) legitimacy of shark fishing regulations and governing authorities; and (v) personal and subjective norms around shark fishing (Table 2). To capture the multidimensional nature of legitimacy, we developed a composite index using five indicators represented by 10-point Likert scale statements (Table 2). Similarly, we developed a composite index of ‘social norms’ using two questions designed to capture fishers’ personal and subjective norms related to shark fishing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptions of dependent variable (shark fishing) and independent variables used in our model to explore the relationship between non-compliance and potential drivers of individual behaviour

| Variable | Description | Data type |

|---|---|---|

| Shark fishing | Whether the respondent reported targeting sharks (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

| Witnessed shark fishing | Whether the respondent had previously witnessed shark fishing (No = 0, Yes = 1) | Dichotomous |

| Perceived non-compliance | Perceived level of shark fishing in Myeik Archipelago (6-point scale) | Ordinal |

| Effects of shark fishing | Perceived effect of shark fishing on shark populations (10-point scale) | Ordinal |

| Legitimacy | Principal component score based on five indicators of legitimacy (Table S2) | Continuous |

| Social norms | Principal component score capturing subjective and personal norms regarding shark fishing (Table S3) | Continuous |

We worked with bilingual, experienced research staff from Myeik University to translate, pilot and implement the surveys in the local language. Surveys were administered face-to-face with fishers, who we identified using convenience and snowball sampling with the help of local assistants in each community. Responses were recorded in English and were regularly checked for consistency.

Data coding and analysis

We inductively coded responses regarding individual and perceived motivations for (non)compliance into broadly defined categories via thematic analysis—an iterative, bottom-up approach in which coding categories are created from the responses as opposed to an existing theoretical framework (Joffe and Yardley 2004). We then explored whether motivations were related to fishers’ awareness of shark fishing regulations by qualitatively assessing whether the occurrence (i.e. relative frequency) of motivations differed between aware and unaware fishers.

To examine how shark fishing was related to individual fisher characteristics and, separately, potential drivers of individual behaviour, we used two Bayesian hierarchical models implemented as linear mixed effects models. To account for the clustered structure of our data (i.e. fishers nested within communities) we a priori set community as a random effect in both models. This ensured more accurate estimation by imposing a correlation structure on data collected from the same community. We assessed collinearity among independent variables (Appendix S2), and standardized continuous independent variables by subtracting their mean and dividing by 2 of their standard deviations to gauge their relative importance as the relative magnitude of their effect sizes. We used weakly-informative prior distributions (Appendix S2), the default recommended for hierarchical linear models with a binary-dependent variable (Gelman et al. 2008). Analyses were undertaken using the statistical computing software R (version 3.5.2, R Core Development Team 2019).

Results

Levels of shark fishing and awareness of regulations

Collectively, 40% of respondents (n = 58) had accidentally or intentionally caught an estimated 4821 sharks in the 12 months prior to participating in the survey. Overall, 24% of respondents (n = 35) self-reported as shark fishers (range 14–45% per community), and 36% reported having witnessed shark fishing. Despite this, 93% of respondents reported that shark fishing does not occur in their community, yet 40% perceived the level of shark fishing to be ‘high’ or ‘very high’ in the Myeik Archipelago.

Overall, 49% of respondents (n = 71) were aware of rules regarding shark fishing, but levels of awareness varied among communities (Table 3). Fishers that reported being aware of regulations surrounding shark fishing (herein, ‘aware fishers’) only cited the nationwide ban—none appeared to be aware of the shark reserves. Approximately, half of aware fishers (52%) had learned about the ban from the Department of Fisheries (via a noticeboard, fishing licence, pamphlet or representative), and 84% considered that the government should be responsible for sharing information about the ban.

Table 3.

Characteristics of respondents (n = 144) across our five study communities located on Thayawthadangyi Island (Don Pale, Lin Long, Palawar), Lampi Island (Makyone Galet) and the Tanintharyi coast (Myeik)

| Don Pale | Lin Long | Palawar | Makyone Galet | Myeik | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households surveyed | 39 | 43 | 11 | 31 | 20 |

| Percent of households surveyeda | 12.7 | 35.0 | 18.0 | 16.2b | n/ac |

| Percent aware of regulations | 61.5 | 53.5 | 64.0 | 25.8 | 45.0 |

| Percent self-reported shark fishers | 35.9 | 14.0 | 45.5 | 19.4 | 20.0 |

| Age (mean) | 41 | 37 | 26 | 39 | 43 |

| Years of formal education (mean) | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Occupations per household (mean) | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Percent boat owners | 69 | 67 | 36 | 90 | 85 |

| Percent migrants | 49 | 40 | 18 | 100 | 25 |

Who is targeting sharks?

In constructing a ‘profile of a shark fisher’, we found strong evidence (i.e. where a parameter’s 95% uncertainty interval did not intersect zero) that shark fishers tended to be younger, as indicated by a negative relationship between reported shark fishing and age (Fig. 2). We also found suggestive evidence that shark fishers tended not to own their own boat (i.e. they worked on a boat owned by someone else), as indicated by a negative relationship between shark fishing and boat ownership (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of a Bayesian hierarchical linear model examining the relationship between shark fishing and fisher characteristics (n = 108). Parameter estimates are highest posterior density medians (points) and associated 80% (thick line) and 95% (thin line) uncertainty intervals (UI). Estimates to the right of the dashed line indicate that the variable was positively related to shark fishing, and statistical significance is inferred where UIs do not intersect zero. Reference categories: Migrant, ‘No’; Aware of regulations, ‘No’; Boat owner, ‘No’

What shark families are being caught and how?

Among fishers who reported catching sharks accidentally or intentionally, nearly all (97%, n = 56) provided information on the species caught at each fishing site. The majority of species listed by fishers were from three families: (1) bamboo and epaulette sharks (Hemiscylliidae: 46.9% overall); (2) requiem sharks (Carcharhinidae: 36%); and (3) hammerhead sharks (Sphyrnidae: 7.6%), however catch composition was variable across sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of catch from each shark family in each study community

| Family | Don Pale | Lin Long | Palawar | Makyone Galet | Myeik |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiscylliidae | 51.7 | 48.8 | 52.2 | 75.0 | 35.6 |

| Carcharhinidae | 28.3 | 39.5 | 47.8 | 25.0 | 38.4 |

| Sphyrnidae | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 15.1 |

| Total | 85.0 | 93.0 | 100 | 100 | 89.0 |

Overall, sharks were most commonly caught using spears (n = 25 fishers, 37% of total catch), trammel, seine and drift nets of various mesh sizes (23 fishers, 35% of catch), long lines (4 fishers, 25% of catch) and trawlers (2 fishers, 2% of catch). Myeik fishers who reported sharks as target or incidental catch (15 fishers, 1188 sharks) primarily used nets (10 fishers, 56% of catch), followed by longlines (3 fishers, 34% of catch), trawlers (n = 2 fishers, 10% of catch) and spears (n = 1 fisher, 0.3% of catch). In contrast, fishers living in the island communities who reported sharks as target or incidental catch (27 fishers, 3633 sharks) primarily used spears (22 fishers, 49% of catch) and, less frequently, nets (13 fishers, 28% of catch) and long lines (3 fishers, 23% of catch).

Where and when are sharks being caught and sold?

Participatory mapping revealed a number of locations where sharks were targeted or observed to be targeted by others (Fig. 3). Fishers travelled an average of five hours to reach sites where they reported catching sharks, and nearly half (45%) of fishing sites were over four hours away. Based on self-reported seasonal fishing activity, shark fishers were most active during the dry season from December through April (peak in March–April). This peak in self-reported shark fishing activity overlapped partially with the period during which shark fishing was witnessed most frequently (March–May). Among fishers who had witnessed other boats targeting sharks (n = 32), 78% reported that these fishers come from Myeik. Fishers from Myeik reported selling their catch at buying centres in Ranong (Thailand), Myeik, and Yangon, whereas fishers from the four island communities reported selling their catch locally (within the community) and to buyers throughout the archipelago (e.g. Myeik, Don Pale, Wae Kyun, Kyun Pon, and Nyaung Mein, Mee Sein, and Kyein Ni Taung, Myo Min Tun).

Fig. 3.

Map of a Thayawthadangyi Island and b Lampi Island, showing locations where fishers reported to have caught sharks (blue) and/or seen other boats catching sharks (orange)

Why is (non)compliance occurring?

Individual motivations for (non)compliance

When self-reported shark fishers (n = 35) were asked why they target sharks, earning money was the most common response (43%, n = 15 fishers), cited by 55% of aware shark fishers (n = 11) and 27% of unaware shark fishers (n = 4). The second most common response was that sharks were caught as a source of food (20%, n = 7), a motivation cited by 10% of aware shark fishers and 33% of unaware shark fishers. Compliant fishers (n = 109) were primarily motivated by a fear of sharks (44%, n = 48) and a lack of capacity (37%, n = 40).

Perceived motivations for (non)compliance

When fishers (n = 144) were asked to provide two reasons why other fishers would target sharks, earning money was the most common response overall (83%, n = 119 fishers), cited by 93% of aware fishers (n = 66) and 73% of unaware fishers (n = 53; Fig. 4a). When asked why other fishers wouldn’t target sharks, a lack of capacity (equipment, resources, and/or knowledge) was the most common response among unaware fishers (44%, n = 32) and overall (40%, n = 57). Among aware fishers, however, the majority (41%, n = 29) felt that others wouldn’t target sharks because it is against the law (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Perceptions of respondents regarding why fishers in the Myeik Archipelago a would target sharks (n = 117 respondents, 129 responses), and b wouldn’t target sharks (n = 111 respondents, 138 responses)

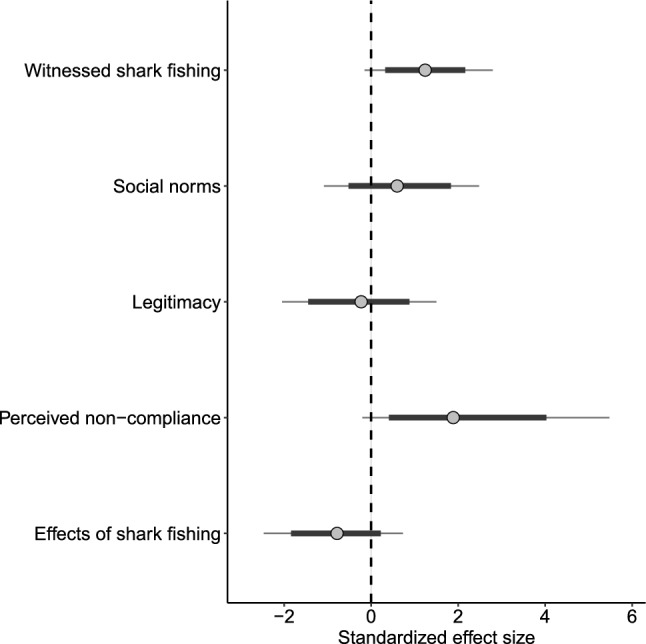

In exploring the potential drivers of individual behaviour of aware fishers, we found suggestive evidence (i.e. where a parameter’s 80% uncertainty interval did not intersect zero) that individual non-compliance was positively related to having witnessed non-compliance, and ‘perceived non-compliance’—the perceived level of shark fishing by fishers in the community (Fig. 5). We found no evidence that self-reported non-compliance was related to social norms or perceived legitimacy (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Results of a Bayesian hierarchical linear model examining the relationship between shark fishing and potential drivers of individual behaviour (n = 47). Parameter estimates are highest posterior density medians (points) and associated 80% (thick line) and 95% (thin line) uncertainty intervals (UI). Estimates to the right of the dashed line indicate that the variable was positively related to shark fishing, and statistical ‘significance’ is inferred where 95% UIs do not intersect zero. Reference categories: Witnessed shark fishing, ‘No’

Discussion

Understanding the levels and potential behavioural drivers of illegal fishing can help contextualize the problem and inform the development of strategies to improve compliance. We found that overall, nearly half of fishers were aware of the nationwide ban on shark fishing, and around one quarter self-reported that they targeted sharks. Shark fishers tended to be younger individuals who did not own their own boat, and perceived shark fishing to be prevalent. Compliant fishers were motivated by a fear of sharks and lack of capacity (equipment, knowledge), whereas food and income were cited as key motivations for non-compliance.

Our study highlights the contextual nature of compliance. In contexts such as the Myeik Archipelago where poverty rates are high and fishers lack alternative sources of income, the incentive to fish illegally is likely to be strong. Indeed, a case study of a small-scale fishing community in Arniston, South Africa found that following implementation of a marine protected area adjacent to the community, illegal harvest of abalone occurred due to fishers’ lack of alternatives (Isaacs and Witbooi 2019). Further, communities with limited interaction with fisheries officers—due to their remote location or the government’s lack of resources, for example—may be less likely to be aware of fishing regulations. This lack of awareness can contribute to non-compliance (Lancaster et al. 2015), and might be exacerbated in areas such as the Myeik Archipelago where low literacy rates and multiple language backgrounds preclude some fishers from accessing information provided exclusively via written material (on fishing licences, pamphlets and noticeboards) in a single language. These factors, combined with a lack of capacity to enforce the rules, could produce conditions that lead to non-compliance (e.g. Gill et al. 2017).

The results of our study demonstrate that, within the context described above, some fishers may be more likely than others to break the rules. In our study communities, shark fishing was more common among younger fishers who work as crew on a boat owned by older, wealthier fishers. Younger fishers might be more likely to target sharks simply because they are better able to cope with the physical demands of hookah diving with spears—the fishing method most frequently used by shark fishers in our study. Further, young people might be more willing to fish illegally as a means to earn the income necessary to pursue alternative livelihood opportunities (Fabinyi 2007). Indeed, approximately half of shark fishers in our study reported that hookah diving is dangerous and tiring, and that they would rather be doing something else but they continue fishing due to a lack of alternatives (MacKeracher, unpubl.). These findings suggest that while these fishers currently target sharks, compliance could be increased if fishers were provided safer alternatives that provide similar levels of income.

Shark fishing in the Myeik Archipelago: What, where, when and how

Community level differences in catch composition likely reflects the different gears and/or fishing sites used by fishers in different communities. Shark fishers in island communities reported using spears while hookah diving at night, a finding which likely explains the relatively higher catch of hemiscyliids—a slower moving, nocturnally active group. In contrast, Myeik fishers primarily used gears that can be used at a range of depths (i.e. nets, longlines, trawlers), increasing the potential range of fishing grounds that can be accessed. The use of these gears by Myeik fishers also explains the greater relative catch of sphyrnids.

Our findings regarding the spatial and temporal distribution of shark fishing activity provide some insight into where and when non-compliance is occurring in the Myeik Archipelago. The patterns observed may reflect seasonal movements and habitat use of sharks in the area, however, data to support this explanation are currently lacking. This information could be collected through tracking studies or baited remote underwater video, both of which have been extensively used to assess habitat use and movement of sharks (White et al. 2013; Heupel et al. 2018). The temporal pattern in shark fishing activity may also reflect seasonal differences in fishing conditions, as peak shark fishing activity occurred during the same months offering the most favourable weather conditions for fishing (December to April). Regardless of the explanation, these results suggest that spatially and temporally targeted on-water patrols may be useful. However, given that the Department of Fisheries currently lacks patrol vessels for enforcement, a more feasible option would be for fisheries officers to conduct targeted land-based patrols of landing sites and markets. Communities could potentially play a role in monitoring their local fishing grounds (Pomeroy et al. 2015), however the spatial extent of shark fishing may be beyond what can be feasibly monitored by local communities.

Our direct estimates of individual non-compliance conflict with the perceived level of non-compliance—nearly all reported that shark fishing does not occur in their community, despite the fact that 24% were targeting sharks. This inconsistency may reflect a social bias among rule-breakers, who are often reluctant to admit to engaging in illegal behaviour (Tourangeau and Yan 2007). Alternatively, when asked about the prevalence of shark fishing in their community, fishers may have interpreted ‘shark fishing’ to be larger scale commercial fishing activity undertaken by dedicated shark fishing vessels based on the mainland. Indeed, in a 2015 survey of fishers in Thayawthadangyi, most reported that shark fishing is conducted by fishers from Myeik (Howard et al. 2015). In this case, fishers may not consider members of their community to be shark fishers even if they are aware that sharks are targeted by fishers in their community.

Our findings regarding how sharks are caught and where they are sold can contribute to Myanmar’s broader shark conservation efforts. Myanmar is currently redrafting its National Plan of Action for sharks, and our study can guide the practical implementation of the new plan through targeted measures to reduce shark bycatch and improve collection of species-level landings and trade data at key ports and markets. Our study confirms that sharks caught in the Myeik Archipelago are being sold to neighbouring Thailand (Howard et al. 2015), currently the world’s top exporter of shark fins despite having limited domestic shark stocks (Dent and Clarke 2015). Regional cooperation is needed to improve monitoring and species-level data collection at landing sites and markets so that both countries can meet their CITES obligations (BOBLME et al. 2015b; Bräutigam et al. 2016).

Drivers of non-compliance in small-scale fisheries

To date, research on fisheries compliance has focused on commercial or recreational fisheries in higher-income countries, with explanations for behaviour emphasising the role of norms and perceptions of management and relevant authorities (Kuperan and Sutinen 1998; Arias et al. 2015). However, the results of our study support the notion that in contexts where the incentive for rule-breaking is strong, such normative influences may play a weaker role in fishers’ decision-making processes. We found that food and income were the most common motivations for shark fishing, suggesting that the desire to meet basic needs can be a strong driver of illegal behaviour in communities dealing with poverty—particularly if there are few, legal marine-based alternatives that provide similar financial profit (Gezelius 2004; Whitcraft et al. 2014; Jaiteh et al. 2016; Booth et al. 2019; Isaacs and Witbooi 2019).

This drive to meet basic needs may also explain why shark fishing did not depend on fishers’ awareness of the shark fishing ban. In contexts such as the Myeik Archipelago, the immediate drive to meet short term survival needs may limit fishers’ capacity to consider the long-term effects of their actions (Mullainathan and Shafir 2013). Indeed, a study exploring the moral justifications for non-compliance demonstrated that non-compliant fishers may justify their behaviour if they perceive survival needs to be of utmost importance (Cepić and Nunan 2017). Further, the fact that the fear of sharks and lack of capacity were the most commonly cited motivations to comply suggests that fishers who currently comply with the regulation might willingly engage in shark fishing if they had the equipment, knowledge and resources to do so safely. This has important implications for shark conservation efforts—in the absence of enforcement, the drive to meet basic survival needs can take precedence over other drivers of behaviour, including any intrinsic motivation or obligation to follow the rules (Cepić and Nunan 2017). Given the strong financial incentive to catch sharks, strategies to improve compliance must address the pressing issues of food security and poverty in these communities, potentially through livelihood diversification strategies.

Rule-breakers are often reluctant to identify themselves for fear of retribution (Tourangeau and Yan 2007), making non-compliance inherently challenging to assess. These challenges are exacerbated in contexts such as Myanmar, where the lack of resources and persistent fear of government makes accurately estimating non-compliance even more difficult. In such contexts, indirect measures such as perceived non-compliance may be a reliable alternative to direct estimates by allowing respondents to mask their own behaviour through impersonality (Fisher 1993). We found that fishers who perceived the level of non-compliance to be high were more likely to be rule-breakers themselves, a finding that is consistent with previous research on compliance in marine protected areas (Hatcher et al. 2000; Arias and Sutton 2013). This pattern may reflect the ‘false consensus effect’, whereby a person tends to overestimate the extent to which their own behaviour is normal (Ross et al. 1977). Alternatively, fishers may decide to engage in shark fishing because they observe the behaviour to be widespread (e.g. Cialdini 2007). While we cannot determine the causal direction of this relationship, the link between individual and perceived non-compliance suggests that the latter is a reasonable proxy for actual non-compliance that could be useful for identifying potential shark fishers.

Improving compliance to achieve positive outcomes for sharks and people

In resource-dependent communities where fishers have few alternative sources of income, shark conservation efforts can benefit from strategies to reduce fishing pressure on sharks through incentives for sustainable alternative livelihoods. In the context of the Myeik Archipelago, tourism is one livelihood opportunity with considerable potential for development (Dearden 2016). However, while there are plans for resort development on some islands (Dearden 2016), most communities in the archipelago currently lack the infrastructure to support tourism (MOECAF 2015). Further, tourism developments have previously failed to deliver their intended benefits (Bennett et al. 2014), in some cases because there is a lack of interest in or capacity to engage with alternative livelihood opportunities (Sofield 1996; Pauly 1997).

Given that local perceptions toward tourism development are largely unknown for the Myeik Archipelago, research is needed to understand (1) communities’ willingness and ability to engage with tourism-related activities; and (2) whether and how tourism aligns with local values, needs, and visions of the future. A number of other factors should also be considered, including the potential socio-cultural and ecological impacts of increased tourism visitation and in-migration of opportunity seekers from the mainland (MOECAF 2015). Finally, community social dynamics—including issues of equity—need to be considered, and capacity building may be necessary to ensure that everyone, including marginalised households, feel empowered to engage in tourism and other new livelihood opportunities (Diedrich et al. 2019). Embedding livelihood development in the local context and supporting communities during the process of transition will help ensure that tourism and other livelihood opportunities optimise conservation and community benefits (Dearden 2016; Wright et al. 2016; Jaiteh et al. 2017).

Education campaigns can contribute to achieving and maintaining fisheries compliance by ensuring that fishers are aware of regulations, why and how they were created, and the negative social and ecological consequences (both immediate and long-term) of non-compliance (Pollnac et al. 2010). In developing these campaigns, however, care is needed to ensure that information is disseminated through the most appropriate channels (e.g. print material, community presentations). Consideration should also be given to context-specific factors that can affect fishers’ access to information, including literacy rates, access to mobile phones, and available time to attend awareness-raising activities. While it is well established that simply providing information is rarely sufficient to change behaviour (Butler et al. 2013; Sutton and Rao 2014), education campaigns will be an important component of strategies to improve fisheries compliance in the Myeik Archipelago, and can complement efforts to support the diversification of fishers’ livelihoods.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the literature on compliance in small-scale fisheries in lower-income country contexts. In exploring fishers’ awareness of, compliance with and perceptions towards shark fishing regulations, we show that shark fishing is common in Myanmar’s Myeik Archipelago, and that the level and geographic extent of shark fishing activity is likely beyond what can be feasibly monitored by local communities. While educational campaigns can contribute to improving awareness and compliance, ensuring compliance over the long term will likely require addressing broader issues of poverty and food security in this area. Future research should focus on exploring the willingness and ability of communities to engage with alternative livelihood opportunities that align with local values and needs. Ultimately, the insights gained from this study can provide guidance to inform the development of strategies to benefit sharks and coastal communities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all community members who participated in this research. We also sincerely thank staff at Fauna and Flora International (Robert Howard, Soe Thiha, Sanay Ko, Soe Tint Aung, Kyaw Zay Ya, Salai Mon Nyi Nyi Lin) and Instituto Oikos (Elisa Facchini, Aung Myo Lwin) for support with logistics and data collection. We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript. This research was supported by the Shark Conservation Fund.

Biographies

Tracy MacKeracher

is a doctoral candidate at Dalhousie University. Her research focuses on understanding and quantifying the social, economic and ecological processes underpinning the sustainability of Nova Scotia’s lobster fisheries.

Me’ira Mizrahi

is a doctoral candidate at James Cook University and Marine Technical Advisor for Wildlife Conservation Society, Myanmar. Her research interests include the socioeconomic dimensions of MPA planning.

Brock Bergseth

is currently a Post-doctoral Researcher at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. His research focuses on understanding the nature an implications of human interactions with ecosystems, and on shaping human behaviour to lead to beneficial social-ecological outcomes.

Khin May Chit Maung

is an Assistant Lecturer at Myeik University. Her research interests include marine plankton, elasmobranch fisheries and socio-economic assessments of fishing communities.

Zin Lin Khine

is a Lecturer at Myeik University. Her research interests include marine plankton and socio-economic assessments of fishing communities.

Ei Thal Phyu

is a Demonstrator at Myeik University. Her research interests include bivalve fisheries and socio-economic assessments of fishing communities.

Colin A. Simpfendorfer

is a Professor at James Cook University. His research interests include the ecology, conservation and management of elasmobranchs globally.

Amy Diedrich

is a Senior Lecturer at James Cook University. Her research interests include exploring how small-scale fishing communities in the tropics respond to social and environmental change, and how this affects their ability to maintain sustainable livelihoods.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Arias A. Understanding and managing compliance in the nature conservation context. Journal of Environmental Management. 2015;153:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias A, Sutton SG. Understanding recreational fishers’ compliance with no-take zones in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Ecology and Society. 2013;18:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Arias A, Cinner JE, Jones RE, Pressey RL. Levels and drivers of fishers’ compliance with marine protected areas. Ecology and Society. 2015;20:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista W, Romero-Canyas R, Smith SL, Fraire J, Effron M, Larson-Konar D, Fujita R. Behavior change interventions to reduce illegal fishing. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2018;5:403. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G., P. Cohen, A.M. Schwarz, J. Albert, S. Lawless, C. Paul, and Z. Hilly. 2014. Solomon Islands: Western Province situation analysis. Project report: AAS-2014-15. Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems.

- Bergseth BJ, Roscher M. Discerning the culture of compliance through recreational fisher’s perceptions of poaching. Marine Policy. 2018;89:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- BOBLME . Assessment of the efficacy of Myanmar’s Shark Reserves. Phuket, Thailand: Department of Fisheries (DoF) Myanmar, Fauna & Flora International (FFI) and the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem project (BOBLME); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- BOBLME, Department of Fisheries, Myanmar, Fauna and Flora International . Guide to the development of Myanmar’s National Plan of Action for the conservation and management of sharks. Phuket, Thailand: Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Project (BOBLME); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- BOBLME . Situation analysis of the Myeik Archipelago. Phuket, Thailand: Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Booth H, Squires D, Milner-Gulland EJ. The neglected complexities of shark fisheries, and priorities for holistic risk-based management. Ocean and Coastal Management. 2019;182:104994. [Google Scholar]

- Bova CS, Halse SJ, Aswani S, Potts WM. Assessing a social norms approach for improving recreational fisheries compliance. Fisheries Management and Ecology. 2017;24:117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam A, Callow M, Campbell IR, Camhi MD, Cornish AS, Dulvy NK, Fordham SV, Fowler SL, et al. Global priorities for conserving sharks and rays: A 2015–2025 strategy. Cambridge: Global Sharks and Rays Initiative; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Butler P, Green K, Galvin D. The principles of pride: The science behind the mascots. Arlington, VA: Rare; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carr LA, Stier AC, Fietz K, Montero I, Gallagher AJ, Bruno JF. Illegal shark fishing in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy. 2013;39:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Cepić D, Nunan F. Justifying non-compliance: The morality of illegalities in small scale fisheries of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Marine Policy. 2017;86:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB. Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control. Psychometrika. 2007;72:263. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes E. Incorporating uncertainty into demographic modeling: Application to shark populations and their conservation. Conservation Biology. 2002;16:1048–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LN, Krawchuk MA, Dulvy NK. Why have global shark and ray landings declined: Improved management or overfishing? Fish and Fisheries. 2016;17:438–458. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, P. 2016. Blueprint for a Network of Marine Protected Areas in the Myeik Archipelago, Myanmar Fauna and Flora International, Myanmar. Tanintharyi conservation report 39, Yangon.

- Diedrich A, Benham C, Pandihau L, Sheaves M. Social capital plays a central role in transitions to sportfishing tourism in small-scale fishing communities in Papua New Guinea. Ambio. 2019;48:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-1081-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulvy NK. Super-sized MPAs and the marginalization of species conservation. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 2013;23:357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Dulvy NK, Fowler SL, Musick JA, Cavanagh RD, Kyne PM, Harrison LR, Carlson JK, Davidson LN, et al. Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. eLife. 2014;3:e00590. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulvy NK, Simpfendorfer CA, Davidson LNK, Fordham SV, Bräutigam A, Sant G, Welch DJ. Challenges and priorities in shark and ray conservation. Current Biology. 2017;27:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabinyi M. Illegal fishing and masculinity in the Philippines: A look at the calamianes islands in Palawan. Philippine Studies. 2007;55:509–529. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, F., and S. Clarke. 2015. State of the global market for shark products. Technical paper 590: I. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture.

- Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research. 1993;20:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman K, Gabriel S, Abe O, Adnan-Nuruddin A, Ali A, Bidin Raja Hassan R, Cadrin SX, Cornish A, et al. Examining the impact of CITES listing of sharks and rays in Southeast Asian fisheries. Fish and Fisheries. 2018;19:662–676. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, S.L. 2012. First meeting of the signatories to the Memorandum of Understanding on the conservation of migratory sharks, 26. Background Paper on the Conservation Status of Migratory Sharks.

- Gelman A, Jakulin A, Pittau MG, Su YS. A weakly informative default prior distribution for logistic and other regression models. The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2008;2:1360–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Gezelius SS. Food, money, and morals: Compliance among natural resource harvesters. Human Ecology. 2004;32:615–634. [Google Scholar]

- Gill DA, Mascia MB, Ahmadia GN, Glew L, Lester SE, Barnes M, Craigie I, Darling ES, et al. Capacity shortfalls hinder the performance of marine protected areas globally. Nature. 2017;543:665–669. doi: 10.1038/nature21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han NM. Overview on the needs of public awareness for sustainable development in Tanintharyi coastal urban areas. Myeik: Myeik University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher A, Jaffry S, Thébaud O, Bennett E. Normative and social influences affecting compliance with fishery regulations. Land Economics. 2000;76:448–461. [Google Scholar]

- Heupel MR, Kessel ST, Matley JK, Simpfendorfer CA. Acoustic telemetry. In: Carrier JC, Heithaus MR, Simpfendorfer CA, editors. Shark Research: Emerging technologies and applications for the field and laboratory. Marine biology series. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2018. pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K, Tun UT, Latt UKT. Marine conservation in Myanmar—The current knowledge of marine systems and recommendations for research and conservation. Yangon: WCS and MSAM; 2013. p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, R., A. Ahmad, and U.S.H. Shein. 2015. Shark and ray fisheries of Myanmar—Status and socio-economic importance. Report no. 12 of the Tanintharyi Conservation Programme, a joint initiative of Fauna and Flora International (FFI) and the Myanmar Forest Department, FFI, Yangon, and the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem Project (BOBLME).

- Howard, R., Z. Lunn, A. Maung, S.M.N.N. Len, S. Thiha, and S.T. Aung. 2014. Assessment of the Myeik Archipelago Coral Reef Ecosystem, Reef Check Surveys, January 2013 to May 2014. Report no. 5 of the Tanintharyi Conservation Programme, a joint initiative of Fauna & Flora International (FFI) and the Myanmar Forest Department. Yangon: FFI.

- Instituto Oikos and BANCA . Myanmar protected areas: Context, current status and challenges. Milano, Italy: Ancora Libri; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs M, Witbooi E. Fisheries crime, human rights and small-scale fisheries in South Africa: A case of bigger fish to fry. Marine Policy. 2019;105:158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiteh VF, Lindfield SJ, Mangubhai S, Warren C, Fitzpatrick B, Loneragan NR. Higher abundance of marine predators and changes in fishers’ behavior following spatial protection within the world’s biggest shark fishery. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2016;3:43. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiteh VF, Loneragan NR, Warren C. The end of shark finning? Impacts of declining catches and fin demand on coastal community livelihoods. Marine Policy. 2017;82:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks DF, Yardley L, editors. Research methods for clinical health psychology. London: Sage; 2004. pp. 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Keane A, Jones JP, Edwards-Jones G, Milner-Gulland EJ. The sleeping policeman: Understanding issues of enforcement and compliance in conservation. Animal Conservation. 2008;11:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Krakstad J, Michalsen K, Krafft B, Bagøien E, Alvheim O, Strømme T, Tun MT, Tun AST. Cruise report Dr. Fridtjof Nansen Myanmar ecosystem survey, 13 November–17 December 2013. Bergen: Institute of Marine Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperan K, Sutinen JG. Blue water crime: Deterrence, legitimacy, and compliance in fisheries. Law and Society Review. 1998;32:309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster D, Dearden P, Ban NC. Drivers of recreational fisher compliance in temperate marine conservation areas: A study of rockfish conservation areas in British Columbia, Canada. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2015;4:645–657. [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, Sacks A, Tyler T. Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs. American Behavioural Scientist. 2009;53:354–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF). 2015. Status report on Myanmar’s designated ecotourism sites. http://www.gms-eoc.org/resources/status-report-on-myanmar-s-designated-ecotourism-sites. Accessed 20 April 2019.

- Ministry of Hotels and Tourism (MOHT) Myanmar. 2013. Myanmar Tourism Master Plan 2013–2020. Nay Pyi Taw.

- MOECAF and Oikos . Lampi Marine National Park: General management plan 2014–2018. Yangon and Milano, Italy: Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF) and Myanmar and Instituto Oikos; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mora C, Andréfouët S, Costello MJ, Kranenburg C, Rollo A, Veron J, Gaston KJ, Myers RA. Coral reefs and the global network of marine protected areas. Science. 2006;312:1750–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1125295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullainathan S, Shafir E. Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. London: Macmillan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D. 1997. Small-scale fisheries in the tropics: Marginality, marginalisation, and some implications for fisheries management. In Global trends: Fisheries management: American Fisheries Society symposium 20, ed. E.K. Pikitch, D.D. Huppert, D.D., and Sissenwine, M.P. Bethesda, Maryland: American Fisheries Society.

- Pew Charitable Trusts. 2018. Shark Sanctuaries around the world. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/02/shark_sanctuaries_2018_issuebrief.pdf. Accessed 20 April 2019.

- Pollnac R, Christie P, Cinner JE, Dalton T, Daw TM, Forrester GE, Graham NA, McClanahan TR. Marine reserves as linked social–ecological systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:18262–18265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908266107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy R, Parks J, Reaugh-Flower K, Guidote M, Govan H, Atkinson S. Status and priority capacity needs for local compliance and community-supported enforcement of marine resource rules and regulations in the coral triangle region. Coastal Management. 2015;43:301–328. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Greene D, House P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Russ GR, Alcala AC. Decadal-scale rebuilding of predator biomass in Philippine marine reserves. Oecologia. 2010;163:1103–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00442-010-1692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, H., S. Thiha, M. Pontillas, and E.M. Ponce de Leon. 2014. Socio-economic baseline assessment: Thayawthatangyi and Langann Islands, Myeik Archipelago, Myanmar. Report no. 10 of the Tanintharyi Conservation Programme, a joint initiative of Fauna & Flora International (FFI) and the Myanmar Forest Department, FFI, Yangon, and the Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem project (BOBLME).

- Shein, S.H. A. Maung, S.M.N.N. Lin, and U.Z. Lunn. 2013. Socio-economic survey in the villages along Thayawthadangyi Kyun group, Kyunsu Township, Tanintharyi region, Myanmar. Development of a Marine Protected Area Network in Myanmar, Myanmar Marine Programme Report No. 1/2013 Fauna & Flora International.

- Sofield T. Anuha Island Resort, Solomon Islands: A case study of failure. In: Butler R, Hinch T, editors. Tourism and indigenous peoples. Boston: International Thomson Business Press; 1996. pp. 176–202. [Google Scholar]

- St John FA, Edwards-Jones G, Gibbons JM, Jones JP. Testing novel methods for assessing rule breaking in conservation. Biological Conservation. 2010;143:1025–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Sutinen JG, Kuperan K. A socio-economic theory of regulatory compliance. International Journal of Social Economics. 1999;26:174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RI, Rao H. Scaling up excellence: Getting to more without settling for less. New York: Crown Publishing Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:859. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers H, Archer LJ, Mwedde G, Roe D, Baker J, Plumptre AJ, Rwetsiba A, Milner-Gulland EJ. Understanding complex drivers of wildlife crime to design effective conservation interventions. Conservation Biology. 2019;33:1296–1306. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RA, Addison J, Arias A, Bergseth BJ, Marshall NA, Morrison TH, Tobin RC. Trust, confidence, and equity affect the legitimacy of natural resource governance. Ecology and Society. 2016;21:18. [Google Scholar]

- UN FAO. 2013. About the IPOA-Sharks. www.fao.org/fishery/ipoa-sharks/about/en. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- Vincent AC, Sadovy de Mitcheson YJ, Fowler SL, Lieberman S. The role of CITES in the conservation of marine fishes subject to international trade. Fish and Fisheries. 2014;15:563–592. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Paige CA. A global overview of shark sanctuary regulations and their impact on shark fisheries. Marine Policy. 2017;82:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Paige CA, Worm B. Global evaluation of shark sanctuaries. Global Environmental Change. 2017;47:174–189. [Google Scholar]

- WCS . Myanmar biodiversity conservation investment vision. Yangon: Wildlife Conservation Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitcraft S, Hofford A, Hilton P, O’Malley M, Jaiteh V, Knights P. Evidence of declines in Shark Fin demand, China. San Francisco, CA: WildAid; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White J, Simpfendorfer CA, Tobin AJ, Heupel MR. Application of baited remote underwater video surveys to quantify spatial distribution of elasmobranchs at an ecosystem scale. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2013;448:281–288. [Google Scholar]

- White KM, Smith JR, Terry DJ, Greenslade JH, McKimmie BM. Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48:135–158. doi: 10.1348/014466608X295207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHC. 2014. Myeik Archipelago—Tentative lists. http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5874/. Accessed 9 May 2019.

- World Bank, Food Agriculture Organization, and WorldFish. 2012. Hidden harvests: The global contribution of capture fisheries, economic and sector work. Report No. 66469-GLB. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Wright JH, Hill NA, Roe D, Rowcliffe JM, Kümpel NF, Day M, Booker F, Milner-Gulland EJ. Reframing the concept of alternative livelihoods. Conservation Biology. 2016;30:7–13. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.