Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) and fibromyalgia (FM) are both debilitating syndromes with complex polysymptomatology. Early research infers that a relationship may exist even though the diagnosis provided may influence the management trajectory. In the absence of a diagnostic test and treatment, this study aims to confirm the symptoms and their severity, which may infer a relationship and influence future research.

Method:

A quasi-experimental design was utilised, using Internet-based self-assessment questionnaires focusing on nine symptom areas: criteria, pain, sleep, fatigue, anxiety and depression, health-related quality of life, self-esteem and locus of control. The questionnaires used for data collection are as follows: the American Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Symptom Inventory for CFS/ME (American CDC Symptom Inventory); the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria for FM; Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ); McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ); Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI); Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); Health-Related Quality of Life SF-36 V2 (HRQoL SF-36 V2); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLOC) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES).

Setting and participants:

Participants were recruited from two distinct community groups, namely CFS/ME (n = 101) and FM (n = 107). Participants were male and female aged 17 (CFS/ME mean age 45.5 years; FM mean age 47.2 years).

Results:

All participants in the CFS/ME and FM groups satisfied the requirements of their individual criteria. Results confirmed that both groups experienced the debilitating symptoms measured, with the exception of anxiety and depression, impacting on their quality of life. Results suggest a relationship between CFS/ME and FM, indicating the requirement for future research.

Keywords: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, chronic pain, fatigue, Fibromyalgia, health-related quality of life, musculoskeletal pain, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, pain, sleep

Introduction

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS)/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) and Fibromyalgia (FM) are disabling syndromes, without an established aetiology, a diagnostic test, or curative treatment.1–3 Currently, these complex syndromes are governed by their own individual diagnostic criteria and management direction, but display overwhelming evidence of similar symptoms. The prevalence of CFS/ME is estimated that in general practice, 10 patients in 10,000 (0.4%) are likely to have CFS/ME.4,5 The prevalence of FM has been recorded as 2%–3% of the population.5

Early research addressing the similarities of CFS/ME and FM dates back to the 1990s, most of which were preformed prior to the development and publishing of the accepted American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria6 for the diagnosis of CFS/ME (Table 1) and when the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)7 diagnostic criterion for FM was in its infancy. These may be obsolescent but are relevant in the context of the current research. Much of the literature available may discuss CFS/ME and FM together; however, little research actually investigates whether the symptom experience is the same.1,4,8–14 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)8 published guidelines in 2007 for the management of CFS/ME, which are currently under review. CFS/ME comprises a broad range of complex symptoms which include headaches, muscle aches and pains and/or joint pains.8 FM is characterised by a chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain which persists for ⩾3 months, with pain in 11 of the 18 identified pain points (Figures 1 and 2 illustrated by the dots on the body diagrams).2,7 Symptoms include flu-like and gastrointestinal symptoms; pain; fatigue; sleep disturbance; anxiety and/or depression; impact on self-esteem and reduced quality of life.8,14 Evidence suggests that pain is one of the prominent symptoms associated with both syndromes, although historically this has been one of the dividing factors during diagnosis, when the similarities between these syndromes outweigh the differences.7,8,11,15,16 Confirming a diagnosis of CFS/ME or FM is a long and complex processes due to the subtle differences in the initial presenting symptoms.8,11,14 Evaluating the evidence presented in context with medical advances and increasing investment in research, suggested a need to revisit this area of study. Considering these issues and to provide the most appropriate evidence-based care, it is important to investigate these syndromes, as similar management strategies may be beneficial for both groups.

Table 1.

US case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome.6

| 1a. Medically unexplained chronic fatigue, of new onset ⩾6 months, which is b. Not substantially alleviated by rest, not the result of ongoing exertion, c. Substantial reduction in occupational, educational, social and personal activities. d. Anxiety and depression are not always excluded The following conditions, if present, exclude diagnosis of CFS: past or current major depression with melancholic or psychotic features, delusional disorders, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, or alcoholic or substance abuse within 2 years before the onset of CFS or any time afterward. |

| 2. ⩾ 4 or more symptoms, occur for ⩾6 months. These are Self-reported persistent or recurrent impairment in short-term memory or concentration severe enough to cause substantial reductions in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities (a) Sore throat (b) Tender cervical lymph or axillary lymph nodes (c) Muscle pain (d) Multiple joint pain without joint redness or swelling (e) Headaches of a new type, pattern or severity (f) Unrefreshing sleep (g) Post exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours |

CFS: chronic fatigue syndrome.

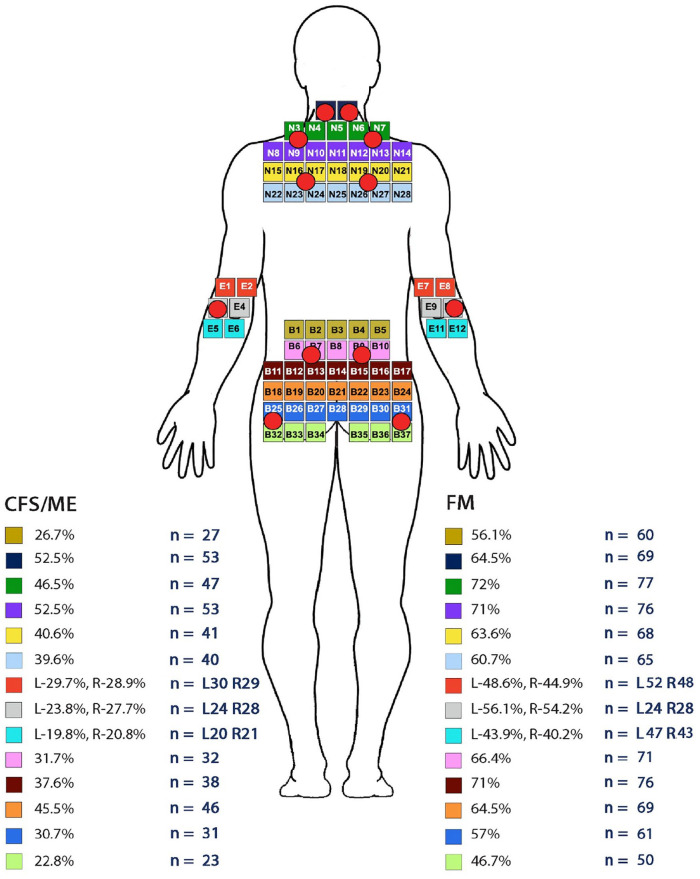

Figure 1.

Results for CFS/ME and FM painpoints from the posterior view of the adapted MPQ body diagram incorporating the ACR pain Points. © NHS Scotland.

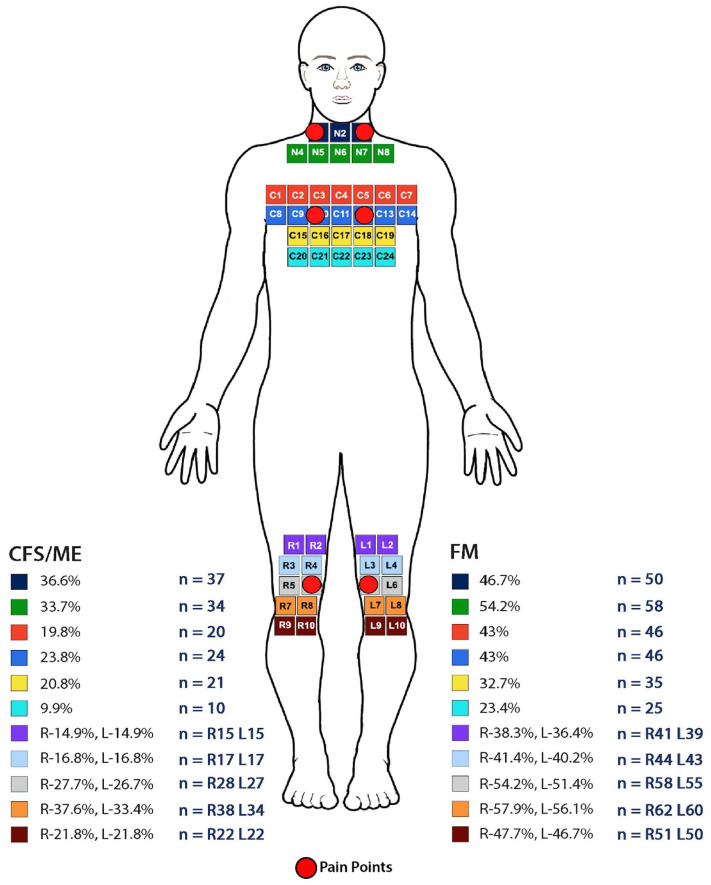

Figure 2.

Results for CFS/ME and FM pain points from the Anterior view of the adapted MPQ body diagram incorporating the ACR pain points © NHS Scotland.

The purpose of this, the first phase, was primarily to confirm the symptoms and their severity in CFS/ME and FM and to identify any occurring themes. At present, in the absence of evidence confirming that CFS/ME and FM share the same underlying pathology, it may be reasonable to suggest they have strong overlapping symptoms, which should be afforded all the same management options. The evidence presented will create the foundation for the second phase to establish whether a relationship exists between the symptoms of CFS/ME and FM.

Methods

Participants

People self-selected to participate and were recruited through advertisements on the Internet and through CFS/ME and FM self-help groups. Participants aged ⩾16 with a confirmed diagnosis of CFS/ME or FM by a general practitioner (GP) or a specialist were included. Participants with CFS/ME were required to satisfy the requirements of the American CDC criteria for CFS/ME6 and participants with FM were required to satisfy the ACR criteria.7 Suitability for inclusion was based on screening answers to the questions. Exclusions were as a result of any additional chronic conditions or anxiety and/or depression, self-diagnosis or incomplete data sets.

Consent

A Web-based template was designed to capture data using a number of questionnaires. Informed consent was confirmed electronically and may have been retracted up to the point of data analysis. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the appropriate university.

Data collection

Nine questionnaires had formerly been subject to validity and reliability checks and reflect the main symptoms and issues which impact people with CFS/ME and FM (Table 2). These sections comprise the disease-specific questionnaire for CFS/ME, the American CDC Symptom Inventory and the diagnostic criterion for CFS/ME6,17 and FM, the ACR diagnostic criterion for FM7 and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ).20,21,43

Table 2.

Description of questionnaires used for data collection.

| Symptom | Questionnaire | Purpose | Scoring | Reliability | Validity | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific questionnaire/criteria | ||||||

| Diagnostic criteria for CFS/ME | American Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) diagnostic criteria for CFS/ME Symptom Inventory | Diagnostic criteria. See Table 1. In addition measures, frequency, intensity and duration of eight symptoms | No cut-off scores ⩾6 months of symptoms more than 4 | Good Cronbachs alpha (α) ranging from 0.82–0.91 r ⩾ 0.7717–19 |

Good Significant correlations r = 0.64–0.94(p < 0.001)17,18 |

Fukuda et al.6

Wagner et al.17 |

| Diagnostic criteria for FM | American College of Rheumatology Diagnostic Criteria for FM | Diagnostic criteria for FM. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate pain points |

No cut-off score ⩾11 out of 18 tender points | N/A | N/A | Wolfe et al.7 |

| Symptom experience of FM | The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) | Comprises 20 items to assess the impact of symptoms of FM on patients’ daily lives and their response to any management/treatment offered. Questions address patient’s function, pain level, fatigue, sleep disturbance and psychological distress | Scores ⩾50 confirmed FM ⩾70 Severe FM | Good α = 0.72–0.93 r = 0.58–0.8320,21 |

Good Significant correlations with the arthritis impact scale (p < 0.0001)22 |

Burckhardt et al.21 |

| Generic questionnaire | ||||||

| Pain | McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) | Measures frequency and intensity of pain, namely: affective, evaluative, sensory and miscellaneous. There is a body diagram to indicate areas of pain, 72 descriptor words to assess pain and a pain rating intensity scale. Each section is scored based on the guidelines | No cut-off score. Higher scores are indicative of an increased level of pain | Good α > 0.9 r ⩾ 0.89 (p ⩽ 0.001)23,24 |

Good Coefficients ranging between 0.3 and 0.423 |

Melzack23 |

| Fatigue | Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) | Measures 20 items on 5 dimensions: general, physical, mental, reduced motivation and reduced activity. Each dimension contains four items, two items relating to fatigue and two items which are contra-indicative of fatigue | Scores range from 4 to 20. Domains should not be summed together. High scores indicative of high levels of fatigue. A score of ⩾10 on the reduced activity subscale on the reduced activity subscale is indicative of fatigue, and severe fatigue is highlighted by a score of ⩾13 on the general fatigue scale | Good α > 0.80 with average of 0.84 Stability r ⩾ 0.7225,26 |

Good p < 0.001 High scores 0.77 general fatigue, 0.7 physical fatigue, 0.61 reduced activity, 0.56 reduced motivation mental fatigue 0.23 (p < 0.01)25,26 |

Smets et al.25 |

| Sleep quality | The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | Measures sleep over the period of 1 month. Comprising 19 items generating seven component scores measuring; subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, the use of sleeping medication, and day-time dysfunction | Each scale scores 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), which yields a score from 0 to 21. High scores indicate poor sleep quality and a global score of ⩾5 indicates sleep disturbance` | Good α > 0.83 Mean component scores r = 0.58 Individual items α > 0.83 r ⩾ 0.85 (p < 0.0001)27–29 |

Good r = 0.33 (p < 0.001)27,28 |

Buysse et al.27 |

| Quality of Life | The SF-36 V2 Questionnaire (SF-36 V2) | Comprises 36 questions within 8 domains of health namely: pain general health, vitality, physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations through physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health including anxiety, depression, loss of behavioural/emotional control and physiological well being Results in two summary components of health physical and mental well-being of the patient. Aims to identify the positive and negative aspects of health which are most important to patients |

Score on scale from 0 to 100, which represent the highest level of functioning. Poor HRQoL scores ⩽35, ⩾than 60 best HRQoL | Good α > 0.7 in all aspects except emotional role α > 0.630–32 |

Good Construct validity measuring >0.731 |

Ware and Sherbourne33 |

| Anxiety and depression | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Measure anxiety and depression in non-psychiatric populations Comprises 14 questions. Seven questions for anxiety (HADS-A) and seven questions for depression (HADS-D) | Each question scores 0 to 3. Total scores 0 to 42. No anxiety or depression ⩽ 7, mild 8 to 10, moderate 11 to 15 and severe ⩾ 16 | Good α = 0.93–0.98, t = 0.93–0.9734–36 |

Good Range = 0.6–0.834,35 |

Zigmond and Snaith34 |

| Ability to approach Illness | Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Form C (MHLOC Form C) | Measures self-related beliefs, comprised four scales namely: internal, chance, doctors and other people. Internal and chance scales comprise six questions; doctors and other people comprise three questions. A total of 18 questions | Measured on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from: 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 6 ‘strongly agree’. Scores on the internal and chance subscales range from 6 to 36, with the doctors and other people subscales, scores ranging from 3 to 18, higher scores suggest stronger beliefs in that area. The minimum score is 3 and the maximum is 108 | Good α = 0.60–0.75 Internal consistency measures = 0.71–0.87 t > 0.8037,38 |

Good r = 0.38–0.65 (p < 0.001)37,38 |

Wallston et al.37

Michielsen et al.38 |

| Self-esteem | The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) | Measures 10 items related to self-esteem. Includes feelings of self-worth and self-acceptance with 5 positive-worded questions and 5 negatively worded questions. The negative items have their scores reversed prior to the analysis | Each question measured on a 4-point scale. One total score. Results range from 0 to 30. Scores ⩽15 suggests low self-esteem | Good α = 0.78–0.89 t = 0.63–0.92 Internal consistence 0.7739,40 |

Good r = 0.57–0.79 (p < 0.01)41,40 |

Rosenberg42 |

CFS/ME: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis; CDC: Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; FM: Fibromyalgia; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; MFI: Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SF: short-form; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MHLOC: Multidimensional Health Locus of Control; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

The remaining questionnaires measured symptoms identified, as follows: the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ);23 the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI);27 the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI);25 the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS);34 the health-related quality of life short-form 36 V2(HRQoL SF-36 V2) questionnaire;33 the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLOC Form C)44 and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES).42 Each questionnaire had its own discrete set of instructions, with a consent section at the beginning, detailed in Table 2.

In addition, questions were posed to collect demographic and comprehensive information on the sample. Details of the research were presented to facilitate the participants submitting their consent. Data were manually screened to confirm whether all questionnaires were fully completed and submitted, prior to analysis.

Results

Descriptive statistics were used to report demographic details. Individual scoring methods for each of the questionnaires confirmed participant’s symptom experience, whether they satisfied the requirements of the American CDC Criteria for CFS/ME6 and the ACR criteria for FM.7

Descriptive analysis

The final sample comprised CFS/ME (n = 101) and FM (n = 107) participants. All were aged ⩾16, with the age ranging between 17–75 years, and all were eligible for inclusion. Incomplete data sets were omitted. The mean (M) age of the CFS/ME (n = 101) group was M = 45.52 years, and the standard deviation (SD) was 12.52, and for FM (n = 107), M = 47.20, SD = 10.77. The CFS/ME sample comprised 85.2 % (n = 86) females and 14.8 % (n = 15) males. The FM group comprised 88.9% (n = 95) females and 11.2% (n = 12) males.

CFS/ME (45.5%; n = 46) participants were more readily diagnosed by a GP. In the case of FM, a greater portion were diagnosed by a rheumatologist (57.9%; n = 62).

All participants with CFS/ME confirmed that they had experienced their symptoms for the required ⩾6 months, and ⩾3 months for an FM diagnosis.7,15 The CFS/ME group experienced their symptoms for a M = 10.69 years and SD = 8.91 years, ranging from 1 to 37 years. Participants with FM experienced symptoms for, ranging from 1 to 28 (M = 12.62; SD = 9.85) years.

All participants experienced more than the minimum requirement of ⩾5 symptoms listed by the American CDC criteria, 7.9% CFS/ME (n = 8) and FM 1.8% (n = 2) groups. With both groups experiencing ⩾4 symptoms confirming the requirements of the CFS/ME criteria.6,17 The maximum number of eight additional symptoms was experienced by the CFS/ME 49.0% (n = 51) and FM 59.8% (n = 61) groups.

The CFS/ME group (n = 101) had a median score of 8 and mode of 6 pain points, below the minimum requirement of 11. The FM (n = 107) group presented with a median of 14 and mode of 18 pain points, based on the ACR diagnostic criteria for FM,7 exceeding the minimum required number of 11 pain points. The most frequent number of pain points reported by the CFS/ME group were 6 (n = 14), followed by 10 and then 8 pain points (n = 12). In the FM group, the most frequently reported number of pain points were 18 (n = 31 participants) followed by 16 and 14 (n = 14 participants). The total number of participants with ⩾11 pain points for CFS/ME was 29.7% (n = 30) and FM was 76.6% (n = 82). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the areas of the body based on the MPQ, which incorporates the ACR criteria for FM pain points, where participants indicated they experienced their pain.

The total numbers of pain points were calculated by assessing the areas where participants indicated their pain was located. The main areas identified by both groups were the cervical areas 52.5% (n = 53), CFS/ME and for FM 64.5% (n = 69) and the upper shoulders 52.5% (n = 53), for CFS/ME and 72% (n = 77), for FM (Figure 1). In addition, 66.4% (n = 71) of FM participants experienced pain in their lower backs. This was also the second most problematic area of pain recorded for the CFS/ME group 31.7% (n = 32) to 45.5% (n = 46); all these areas included the ACR pain points (Figure 1). A higher portion of the FM group reported pain in these areas when compared to the CFS/ME group.

The main areas of pain identified for the anterior view of the body (Figure 2) were the neck for 36.6% (n = 37) for the CFS/ME group, and 54.2% (n = 58) of the FM group, but in this instance, no pain points were included. The chest area, which includes the pain points, was found to be problematic for both groups, with 43.0% (n = 46) of the FM participants and 23.8% of the CFS/ME participants selecting this area. In addition, participants were able to indicate areas of the body they experienced pain which did not incorporate the ACR pain points, concluding that pain was experienced in multiple areas of the body including the face and head, which are not indicative of the ACR pain points for diagnosis.

Table 3 presents the results for the participants mean scores for the individual questionnaires for both groups.

Table 3.

Description of the valid and reliable questionnaires to measure the symptoms in the CFS/ME and FM groups.

| Variable | Mean score CFS/ME | Mean score FM | Cut-off scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| American CDC symptoms inventory | |||

| Sore throat | 3.79 | 3.59 | |

| Tender lymph nodes and or swollen glands | 4.60 | 4.25 | |

| Fatigue after exertion | 12.43 | 12.99 | |

| Muscle aches and pains | 9.51 | 13.79 | |

| Joint pain | 7.78 | 11.48 | |

| Unrefreshing sleep | 10.97 | 13.19 | |

| Headaches | 6.27 | 6.96 | |

| Memory and or concentration problems | 9.37 | 9.62 | |

| Total degree of distress | 64.72 | 75.87 | N/A |

| FIQ | |||

| Total physical impairment | 57.55 | 64.89 | |

| No of days felt well | 8.28 | 8.49 | |

| No of days missed work | 5.48 | 5.80 | |

| Impact of symptoms on work | 7.04 | 7.50 | |

| How bad pain has been* Mdn | 7.0 | 8.0 | |

| How tired have you been* Mdn | 9.0 | 9.0 | |

| Feeling in the morning | 6.65 | 7.97 | |

| Morning stiffness* Mdn | 7.0 | 8.0 | |

| How tense/nervous | 4.50 | 5.64 | |

| How depressed or blue | 4.21 | 5.48 | |

| Overall score FIQ | 62.97 | 70.60 | ⩾50 confirmed FM ⩾70 severe FM |

| MPQ | |||

| Number of pain points | 8.49 | 13.59 | |

| Total sensory score | 15.10 | 19.36 | |

| Total affective score | 7.53 | 10.57 | |

| Total evaluative score | 2.89 | 3.76 | |

| Total score miscellaneous | 5.71 | 7.97 | |

| Sum of all dimensions of MPQ | 31.23 | 41.65 | Scores between 24% and 50% of total score confirm severe pain |

| MFI | |||

| Total score general fatigue | 16.60 | 16.83 | |

| Total score physical fatigue | 16.49 | 16.46 | |

| Total score reduced activity | 15.09 | 14.91 | |

| Total score reduced motivation | 12.90 | 13.20 | |

| Total score mental fatigue | 15.13 | 15.20 | |

| PSQI | |||

| Sleep duration | 1.08 | 1.10 | |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.82 | 1.85 | |

| Sleep latency | 1.96 | 1.99 | |

| Day dysfunction due to sleepiness | 2.05 | 2.11 | |

| Sleep efficiency | 1.61 | 1.74 | |

| Overall sleep quality | 2.02 | 1.93 | |

| Medication to sleep | 1.39 | 1.45 | |

| Total score PSQI | 11.94 | 12.18 | ⩾5 poor sleep quality |

| SF-36 V2 | |||

| Physical functioning | 38.81 | 27.10 | |

| Social functioning | 31.44 | 31.78 | |

| Role physical functioning | 23.39 | 22.61 | |

| Role mental functioning | 64.27 | 51.79 | |

| Mental health | 59.65 | 51.82 | |

| Vitality | 14.48 | 13.84 | |

| Pain | 38.29 | 22.42 | |

| General health | 26.07 | 25.85 | |

| Change in health | 41.58 | 30.14 | Scores of 0 best health scores close to 100 poor health |

| HADS | |||

| Total anxiety | 8.52 | 10.60 | |

| Total depression | 8.30 | 10.10 | |

| Total score HADS | 16.82 | 20.70 | ⩽7 no anxiety or depression, 8–9 borderline case, ⩾11 anxiety and depression |

| MHLOC | |||

| Internal sum | 17.66 | 19.03 | |

| Chance | 17.76 | 16.97 | |

| Doctors | 7.46 | 8.10 | |

| Other people | 8.29 | 8.0 | High scores in particular area confirm beliefs in that area |

| RSES | |||

| Total RSES | 14.35 | 15.02 | ⩽15 poor self-esteem |

CFS/ME: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis; CDC: Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; FM: Fibromyalgia; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; MFI: Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SF: short-form; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MHLOC: Multidimensional Health Locus of Control; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

FIQ

Results for the FIQ confirm that 61.3% (n = 61) of the CFS/ME group scored ⩾50, indicative of FM symptoms present, and 13.8% (n = 14) of participants scoring ⩾70, indicative of severe symptoms of FM.30 In the FM group, 80.3% (n = 86) of participants scored ⩾50 and 28.0% (n = 30) of participants scored ⩾70. The FIQ total scores for the CFS/ME group ranged between 8.86 and 90.4 and for the FM group were between 12.00 and 96.76.

MPQ

Results for the MPQ, which poses a range of questions relating to different aspects of pain, including sensory, affective, evaluative and miscellaneous, confirmed that a significant amount of pain was experienced by both groups. Although there are no cut-off scores for the MPQ, people with painful conditions will normally have scores ranging from 24% to 50% of the total score with an average of 30%.45,46

MFI

Fatigue was confirmed by both groups on the five individual domains of the MFI (general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation and mental fatigue).25 Scores ranged between 4 and 20, with total scores not recommended. The minimum score identified for the CFS/ME group was 4 for physical fatigue and reduced motivation, and the maximum score was 20; for the remaining items of the MFI, the minimum scores were identified as ⩾5, with the maximum score of 20. In the CFS/ME sample, 99.0% of (n = 100) participants experienced fatigue on each domain of the MFI. In the FM group, the minimum score for general fatigue and physical fatigue was 4, with the minimum score on the remaining domains ⩾5, and the maximum score on all the domains were 20. In the FM sample, 98.1% of (n = 105) participants experienced fatigue on all the domains of the MFI. These results confirmed that both the CFS/ME and FM groups experienced a high level of fatigue, a symptom which is indicative of a diagnosis of CFS/ME and associated with FM.

PSQI

The PSQI45 confirmed poor sleep quality in 43.6% (n = 44) of CFS/ME and 47.7% (n = 51) of FM participants. The number of participants who had taken medication ⩾3 times per month to assist with sleep were 39.6% (n = 40) of the CFS/ME group and 41.1% (n = 44) of the FM group. The minimum total score recorded for poor sleep quality on the PSQI for the CFS/ME group was 5 and the maximum was 20. The minimum total score on the PSQI for the FM group was 3, and the maximum score was 21. These findings confirm that both the CFS/ME and FM groups experienced poor sleep quality.

SF-36 V2

The SF-36 V233 confirmed reduced HRQoL in both groups. Scores closer to 0 suggest impaired HRQoL, and scores closer to 100 suggest the best HRQoL.47 The results presented in Table 3 confirm that participants with CFS/ME and FM have a reduced HRQoL with the mean scores on most of the components below 50. The exceptions were for the mental health and role mental functioning components, where scores were ⩾50, which suggests that participants HRQoL was not affected by their mental health. Role physical function was found to have the greatest impact on both the CFS/ME and FM groups. Role mental function did not have as big an impact on participants’ HRQoL.

HADS

The results for the total score for anxiety on the HADS34 ranged from 0 to 20 and confirmed that out of the total sample of CFS/ME (n = 101) 49.5% (n = 50), and FM (n = 107) 27.1% (n = 29) participants, did not display symptoms of anxiety.48 There was a borderline case of anxiety for 14.9% (n = 15) of CFS/ME and 20.5% (n = 22) of FM participants, with the remaining 35.6% (n = 36) of CFS/ME and 52.3% (n = 56) of FM participants confirmed as displaying symptoms of anxiety.

The total score for depression identified that 37.6% (n = 38) of CFS/ME and 28.0% (n = 30) of FM participants did not display symptoms of depression. There was a borderline case for depression for 32.6% (n = 33) of CFS/ME and 30.8% (n = 33) of FM participants. The remaining 29.7% (n = 30) of CFS/ME and 41.1% (n = 44) of FM participants in this sample expressed symptoms of depression.

The total score on the HADS confirmed that 9.9% (n = 10) of CFS/ME and 2.8% (n = 3) of FM participants did not display symptoms of anxiety and depression. There was a possible caseness for 15.8% (n = 16) of the CFS/ME and 4.8% (n = 5) of FM participants for anxiety and depression. The remaining 74.0% (n = 75) of CFS/ME and 92.5% (n = 99) of FM participants confirmed that they were affected by symptoms of anxiety and depression. These results confirmed that both groups experienced some degree of anxiety and depression, with the FM group displaying higher scores on the HADS than the CFS/ME group.

MHLOC

A total score is not recommended for the MHLOC;44 the scores for the internal and chance scales range between 6 and 36.37 The scores for the doctors and powerful other scales range between 3 and 18. Higher scores on a particular scale suggest stronger beliefs in that area, either internal or external locus of control. The mean score for the internal and chance scale for CFS/ME are just on the median (n = 18), and below the median score (n = 9) for the external scale (doctors and other people). Results for the FM group identify slightly higher scores than the median score for the internal sum and below the median scores for chance, doctors and other people. The minimum score for both groups on the internal and chance scales were 6, where the maximum score was 33, for the CFS/ME group and 35 for the FM group on the internal scale. The maximum result on the chance scale for the CFS/ME group were 33 and for the FM group 32. The minimum score calculated for the doctors and other people scales were 3 for both groups. The maximum score recorded for the CFS/ME group on the doctors domain was 17 and for the FM group was recorded as 18. The maximum score recorded for other people for both groups was 18. The results presented suggest on average the CFS/ME and FM groups present with similar scores.

RSES

The RSES49 scores range from 0 to 30. Results did not confirm that either the CFS/ME or FM groups presented with scores ⩾25. In the CFS/ME group and in the FM group, 36.6% (n = 37) and 53.3% (n = 57) of participants confirmed scores ⩽15, respectively. These results suggest that the FM group experienced a lower degree of self-esteem than the CFS/ME group.

Discussion

Unlike historical research into CFS/ME and FM, this research measured the symptoms of CFS/ME and FM using self-assessment questionnaires to confirm and reaffirm the nature of symptoms associated with CFS/ME and FM. The characteristics, such as age and gender, of the CFS/ME and FM groups are supported by historical findings of CFS/ME and FM. 5,50 Both groups confirmed their diagnosis by satisfying the requirements of the CFS/ME criteria6 and the FM criteria.7

The specialty of clinicians who diagnosed the participants in this sample of CFS/ME and FM is also a characteristic of earlier findings. Diagnosis of CFS/ME by a GP is not unexpected; however, in contrast, people with FM are more readily assessed and receive their diagnosis from a rheumatologist or a GP.51 In contrast, people with CFS/ME are not readily assessed or referred onto specialist services, as supported by the current findings.3 This suggests that people with FM more readily have access to specialist services than patients with CFS/ME.

The results from the CFS/ME group confirmed that not all participants satisfied the minimum of 11 pain points to comply with the requirements of the FM criteria. However, the MPQ presents clear evidence that the CFS/ME group experienced pain in different areas of the body, confirming pain is as debilitating a symptom as in FM. This is revealing as the reviewed FM criteria2 has removed the highly prescriptive pain points and focuses on areas of pain, to assess the patient holistically. Furthermore, there is evidence which highlights that the complex nature of this pain assessment has led to it being performed incorrectly or omitted by clinicians as a diagnostic tool for FM.52 Taking all these factors into consideration, it may be reasonable to conclude in this instance that this sample of participants satisfied the requirements of the FM criteria.8 In contrast, the FM group confirmed that they met the requirements of the CFS/ME criteria.

Pain is widely documented as a defining feature for a diagnosis of FM,2,7 and fatigue has been the primary symptom associated with a diagnosis of CFS/ME.20,53 Taking this into consideration with the results presented from the MPQ, PSQI and MFI confirmed that both groups experienced pain and fatigue which impacted on their HRQoL. The high levels of pain identified reflect the findings from studies comparing CFS/ME and FM with other painful conditions such as chronic pain and arthritis, which identified that their pain was equivocal.54,55 The findings presented from the MFI confirms that the debilitating fatigue that plagues people in CFS/ME is also an issue for people with FM. This suggests that the symptom of fatigue in FM is as much a management priority as pain, as it is a distressing symptom identified as negatively impacting on a patient’s quality of life.25 In view of these findings and current research, this suggests that the individual diagnostic criteria for CFS/ME and FM are sensitive towards the diagnosis they are designed for. Therefore, consideration should be given to reviewing current published guidelines for CFS/ME in view of the arguments provided for not creating guidelines for FM.17

In addition to pain and fatigue, our findings confirmed that both groups experienced poor sleep quality and reduced HRQoL with the list of symptoms being extensive. Furthermore, participants in both groups experienced these symptoms to a debilitating degree, which caused impairment and had an impact on their daily lives. These groups did not confirm high levels of anxiety, depression or low self-esteem, which are in contrast to historical reports, suggesting this is not the main pressing issues in CFS/ME and FM.3,2,49,50 With the current lack of successful management plans and taking these findings into consideration, improvement to HRQoL should be given priority in patients with CFS/ME and FM. This is pertinent, as it has been identified that CFS/ME and FM negatively impact on occupational, social, personal and economical aspects, which are frustrating and devastating for a person who previously enjoyed good health.56,57 These results raise questions regarding compartmentalising the symptoms into either a diagnosis of CFS/ME or FM. Fatigue, the main symptom used to make a diagnosis of CFS/ME and pain, the primary diagnostic symptom of FM, have both been confirmed as problematic for both groups. These findings suggest that there is a grey area between the two diagnoses. The data presented suggest that the similarities between the symptoms measured outweigh any differences. The evidence presented provides compelling debate to recommend that further research in this area is undertaken. This would further investigate the significance of the current findings, to identify whether there maybe ramifications for the classification of CFS/ME and FM and its future management.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the symptom experience of CFS/ME and FM using the methods described. This study brings attention to an area with CFS/ME and FM which has not been researched in a number of years.

Conclusion

This preliminary data provided evidence of a high level of symptoms which impact daily life. Furthermore, the results suggest that both groups experience a high level of pain, which is not always localised to the prescriptive pain areas outlined by the ACR criteria for FM. In addition, both groups experience debilitating fatigue. The strong evidence presented in this first part of the study alludes to the fact that both CFS/ME and FM may have a similar symptoms experience, and this should be afforded more investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tim Duffy for his assistance and guidance in this research and Susan Mitchell, NHS Highland for the illustrations. They thank the Florence Nightingale Foundation and the Band Trust for their scholarship.

Footnotes

Authors’ note: The guarantor is the person willing to take full responsibility for the article, including for the accuracy and appropriateness of the reference list. This will often be the most senior member of the research group and is commonly also the author for correspondence.

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship: P.M. and C.M. conceived the study and were involved in data analysis. P.M. was involved in, gaining ethical approval, recruitment and data analysis. P.M., M.F. and H.W. were involved in the editing process of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript

Disclaimers: We confirm that the work submitted and our views are our own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the works of others.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of the West of Scotland Ethics Committee.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Florence Nightingale Foundation and The Band Trust.

Guarantor: P.M. acts as the guarantor for this study.

Informed consent: Electronic/written informed consent was obtained from the patients for their anonymised information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Pamela G Mckay  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1544-4662

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1544-4662

References

- 1. Romano GF, Tomassi S, Russell A, et al. Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: the underlying biology and related theoretical issues. Adv Psychosom Med 2015; 34: 61–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62(5): 600–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Action for ME. Ignorance, injustice and neglect: an investigation into NHS specialist services provision for people with ME/CFS, 2012

- 4. Johnston S, Brenu EW, Staines DR, et al. The adoption of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis case definitions to assess prevalence: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol 2013; 23(6): 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martinez-Lavin M, Infante O, Lerma C. Hypothesis: the chaos and complexity theory may help our understanding of fibromyalgia and similar maladies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 37(4): 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121(12): 953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheumatol 1990; 33: 160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 53. Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in adults and children. London: NICE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldenburg DL, Simms RW, Geigen A, et al. High frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with chronic fatigue seen in primary care practice. Arthritis Rheumatol 1990; 33: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norregaard J, Bulow PM, Prescott E, et al. A four-year follow-up study in fibromyalgia relationship to chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol 1993; 22(1): 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sullivan PF, Smith W, Buchwald D. Latent class analysis of symptoms associated with chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Psychol Med 2002; 32(5): 881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mehendale A, Goldman MP. Fibromyalgia syndrome, idiopathic widespread persistent pain or syndrome of myalgic encephalomyelopathy (SME): what is its nature? Pain Pract 2002; 2(1): 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geisser ME, Gracely RH, Giesecke T, et al. The association between experimental and clinical pain measures among persons with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur J Pain 2007; 11(2): 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kop WJ, Lyden A, Berlin AA, et al. Ambulatory monitoring of physical activity and symptoms in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 269–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weir PT, Harlan GA, Nkoy FL, et al. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population based retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol 2006; 12: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, et al. The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. Am J Public Health 1997; 87: 1449–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner D, Nisenbaum R, Heim C, et al. Psychometric properties of the CDC Symptom Inventory for assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Popul Health Metr 2005; 3: 8, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16042777 (accessed 12 October 2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vermeulen RCW. Translation and validation of the Dutch language version of the CDC Symptom Inventory for assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Popul Health Metr 2006; 4: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawk C, Jason LA, Torres-Harding S. Reliability of a chronic fatigue syndrome questionnaire. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2006; 13: 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bennett R. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ): a review of its development current version operating characteristics and uses clinical and experimental. Rheumatol 2005; 23: 154–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol 1991; 18: 728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason J. Measuring health status in arthritis. The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis Rheum 1980; 23(2): 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975; 1(3): 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ngamkham S, Vincent C, Finnegan L, et al. The McGill Pain Questionnaire as a multidimensional measure in people with cancer: an integrative review. Pain Manag Nurs 2012; 13(1): 27–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 1995; 39(3): 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin JS, Brimmer D, Maloney EM, et al. Further validation of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory in a US adult population. Popul Health Metr 2009; 7: 18, www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/7/1/18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28(2): 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith M, Wegner T. Measures of sleep. The Insomnia Severity Index, Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (PSD) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Arthritis and Rheum 2003; 49: 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Veiga DM, Cunali R, Bonotto D, et al. Sleep quality in patients with temporomandibular disorder: a systematic review. Sleep Sci 2013; 6: 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. Fibromyalgia and quality of life: a comparative analysis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20(3): 475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B, et al. The factor structure of the SF-36 health survey in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(11): 1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Perrot S, Vicaut E, Servant D, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in France: a multi-step study research combining national screening and clinical confirmation: the DEFI Study (determination of epidemiology of fibromyalgia). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011; 12: 224, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21981821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30(6): 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 52(2): 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCue P, Martin CR, Buchanan T, et al. An investigation into the psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol Health Med 2003; 8(4): 425–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wallston KA, Stein MJ, Smith CA. Form C of the MHLC scales a condition-specific measure of locus of control. J Pers Assess 1994; 63(3): 534–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Michielsen HJ, Van Houdenhove B, Leirs I, et al. Depression, attribution style and self-esteem in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia patients: is there a link? Clin Rheumatol 2006; 25(2): 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. White C, Schweitzer R. The role of personality in the development and perpetuation of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2010; 48: 515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sinclair SJ, Blais MA, Gansler DA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: overall and across demographic groups living within the United States. Eval Health Prof 2010; 33(1): 56–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin CR, Thompson DR, Chan DS. An examination of the psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES) in Chinese acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS). Psychol Health Med 2006; 11(4): 507–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bennett RM, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, et al. Minimal important difference in the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 1304–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr 1978; 6(2): 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilkie DJ, Huang HY, Reilly N, et al. Norrciceptive and neuropathic pain in patients with lung cancer: a comparison of pain quality descriptors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001; 22: 899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marshall R, Paul L, McFadyen AK, et al. Pain characteristics of people with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Musculoskelet Pain 2010; 18: 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr. The MOS short Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 1988; 26(7): 724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 29, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12914662 (accessed 25 May 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Friedberg F, Jason LA. Chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia: clinical assessment and treatment. J Clin Psychol 2001; 57(4): 433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vincent A, Lahrm BD, Wolfe F, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a population-based study in Olmstead County, Minnesota, utilising the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care Res 2013; 65: 286–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Craggs-Hinton C. Living with fibromyalgia (Overcoming Common Problems). New ed London: Sheldon Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hauser W, Wolfe F. Diagnosis and diagnostic tests for fibromyalgia (syndrome). Reumatismo 2012; 64(4): 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mease PJ, Palmer RH, Wang Y. Effects of Malcipran on the multidimensional aspects of fatigue to pain and function pooled analysis of 3 fibromyalgia trials. J Clin Rheumatol 2014; 20: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilkie DJ, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, et al. Use of the McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure pain: a meta-analysis. Nurs Res 1990; 39(1): 36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pirins JB, Van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 2006; 367: 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lowry TJ, Pakenham KI. Health related quality of life in chronic fatigue syndrome: predictors of physical functioning and psychological distress. Psychol Health Med 2008; 13(2): 222–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nunez M, Fernandez-Sola J, Nunez E, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: group cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise versus usual treatment. A randomised controlled trial with 1 year follow up. Clin Rheumatol 2011; 30: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]