The prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) is rising worldwide, creating a significant health issue and an unmet need. The diagnosis and decision to treat NTM-PD are often a challenge, with complex criteria for diagnosis and multiple factors weighing in the decision to treat [1]. The treatment is lengthy and the drugs used often associated with adverse effects. Adherence to NTM-PD management guidelines were found to be suboptimal, impacting treatment success [2], with substantial differences in physicians’ decision to treat and in their adherence to treatment guidelines [2–4].

Short abstract

Patients’ experiences of NTM pulmonary disease highlight important and unmet needs for better pharmacological treatment and education of medical staff https://bit.ly/3mjrlwh

To the Editor:

The prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) is rising worldwide, creating a significant health issue and an unmet need. The diagnosis and decision to treat NTM-PD are often a challenge, with complex criteria for diagnosis and multiple factors weighing in the decision to treat [1]. The treatment is lengthy and the drugs used often associated with adverse effects. Adherence to NTM-PD management guidelines were found to be suboptimal, impacting treatment success [2], with substantial differences in physicians’ decision to treat and in their adherence to treatment guidelines [2–4].

Both the disease and treatment may have severe impacts on multiple aspects of patients’ lives [5–7] with contrasting findings regarding improvement in quality of life (QoL) with treatment [5, 7]. Furthermore, substantial emotional distress may also accompany the process of diagnosis and evaluation, which may take months until a decision to treat is being made [8].

EMBARC, the European Multicenter Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration, is a European Respiratory Society (ERS) clinical research collaboration dedicated to promoting research and care of bronchiectasis [9]. One of the aspects of this collaboration involves working with patient volunteers, coordinated by the European Lung Foundation (ELF) to involve people with bronchiectasis in research and promotion of care [10]. Some aspects of this collaboration resulted in documents focused on various aspects of care [11, 12].

We aimed to find out patients’ experiences and challenges regarding NTM-PD diagnosis and treatment. We conducted a survey among people who self-identified as having bronchiectasis and/or NTM-PD. The survey was developed in collaboration between EMBARC and the ELF and their bronchiectasis patient advisory group, and translated into nine languages (Arabic, French, German, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Russian). The survey consisted of 25 questions regarding various aspects of NTM-PD clinical features, diagnostic efforts, decision to treat, and treatment modality, duration and outcomes. The full questionnaire and report may be found on the ELF website: www.europeanlunginfo.org/bronchiectasis/news/ntm-report. As this was an anonymous survey, Helsinki approval was not required.

The survey was available for responses between May 2019 and January 2020 on the ELF website and was advertised through bronchiectasis clinics and EMBARC websites and newsletters. In total, 361 people responded to the survey from Europe (n=231), North America (n=85), South America (n=7), Asia (n=6), The Middle East (n=8) and Australia/New Zealand (n=12). Of the 361 survey responses, there were 14 exclusions due to respondents not having bronchiectasis or NTM-PD. Of the 347 respondents who were eligible for data analysis, 152 (44%) had isolated NTM in their sputum. Overall, 152 (44%) were identified as having bronchiectasis and NTM-PD, 173 (50%) as having bronchiectasis without NTM-PD, and 19 (5.5%) had NTM-PD without bronchiectasis; 85% were female and 51% were between 51 and 70 years of age, and the most common species (60%) was Mycobacterium avium/intracellulare (MAC).

Most of the respondents (118 of 146, 81%) had been offered treatment; however, only a minority of them (35%) successfully completed treatment, 37% were still taking treatment and in 28% treatment was stopped without success. Treatment duration was reported to be 2 years or longer in 19%, between 1 and 2 years in 24%, and 12 months or less in 20%. Of the respondents who were not offered treatment (27 respondents, 19%), several reasons were given: the species was not causing harm (36%), there were expected adverse effects of medications (36%) or resistance to available drugs (4%). In 32%, however, no explanation was offered, or the respondent did not know the reason. Sex, age, country of origin and NTM species were not different between the whole group and those who were offered treatment.

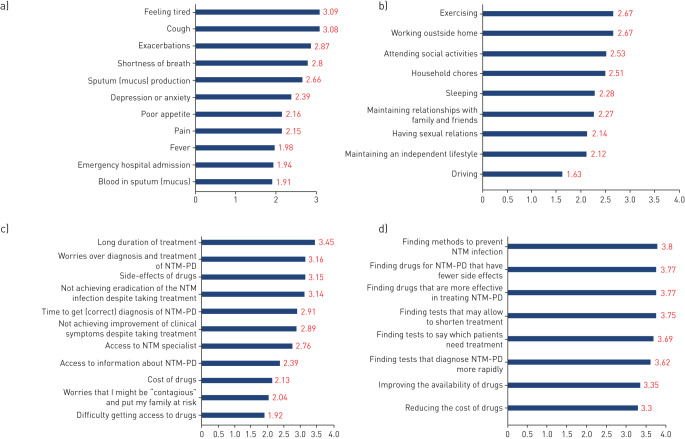

The top three challenging issues for those diagnosed with NTM-PD were rated as “Feeling tired”, “Cough” and “Exacerbations” (figure 1a), with limitations of activities impacted to a lesser extent (figure 1b). Respondents also highlighted the impact of adverse effects of treatment, anxiety around dealing with their condition and the impact on their QoL. Overall, 113 out of 132 (86%) patients stated that their disease had limited their spouses’ QoL “a little” (30%), “much” (30%) or “very much limited” (11%). The most difficult aspects of the management of NTM-PD were identified as: “Long duration of treatment”; “Worries over diagnosis and treatment of NTM-PD” and “Side-effects of drugs” (figure 1c). Interestingly, the issue of drug-related adverse events, while experienced by patients and expressed as a reason for not treating in 36% of untreated patients, was stated as a cause for treatment discontinuation in only 8% of patients.

FIGURE 1.

Patient grading of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) and management impact and needs. a) “Which of the following issues were most challenging?” (n=135). Weighted average rating scale (1–4) where 1 is “not an issue” and 4 is “very difficult”. b) “Rate how your daily activities are limited by NTM-PD” (n=134). Weighted average rating scale (1–4) where 1 is “not limited at all” and 4 is “very much limited”. c) “Which aspects concerning management of NTM-PD posed a challenge for you?” (n=132). Weighted rating scale (1–4) where 1 is “not difficult” and 4 is “very difficult”. d) “What issues need more attention to improve the management of NTM-PD?” (n=135). Weighted average rating scale (1–4) where 1 is “unimportant” and 4 is “very important”.

All the issues needing attention to improve management of NTM-PD (figure 1d) were rated between “Important” and “Very important” when all responses were averaged. The top three issues were: “Finding methods to prevent NTM infection”, “Finding drugs for NTM-PD that have fewer side-effects” and “Finding drugs that are more effective in treating NTM-PD”. Many respondents highlighted the urgent need to raise awareness of NTM among all healthcare professionals including primary care physicians and finding ways to prevent re-infection. Additional important points raised included the need for faster diagnosis, access to NTM-PD specialists and more research into prevention.

Treatment of NTM-PD is complicated by poor success rates, which may be caused by a combination of suboptimal efficacy and toxicity of available medications. In our survey of people who had been treated for NTM-PD, 60% of whom reported MAC infection, successful completion of treatment was uncommon, reported in only 35% of the respondents; 55% are no longer being treated. This finding is in agreement with previously reported “real life” studies, reporting cure rates as low as 27.6% [4] and 56.5% [2].

Some of the symptoms that were rated by respondents as troublesome were found in the recent “NTM module” QoL tool [5], especially “poor appetite” and “fever”. However, in the current survey more weight was given by respondents to symptoms usually associated with bronchiectasis such as “cough” and “exacerbations”. It may indeed be difficult to attribute symptoms to NTM or bronchiectasis if both coexist.

One issue raised by respondents is the need for better education of primary care physicians regarding the diagnosis and relevance of NTM. This issue continuously receives patients’ attention in regard to bronchiectasis in general [13]. Education may result in better awareness of NTM-PD, but also possibly better treatment success rates, as recently demonstrated [2]. Among the many important issues raised by respondents, including developing methods to improve the accuracy and time of diagnosis, prevention and treatment, improvement of education of both patients and primary care personnel may be one of the simplest goals to meet, with an expected tremendous impact on patients’ health and well-being.

One of the limitations of this survey is its availability on internet only. This may have caused a bias towards respondents with a higher level of education and younger age. End-stage patients may have been too unwell to access this survey, and the results were based on self-report, and so we could not ascertain the appropriateness of clinical decisions. The online format and need for multiple languages prevented us from using a validated QoL questionnaire [5]. However, the age and sex distribution of our respondents was typical of NTM-PD patients previously described [14–16]. Translations into 10 languages ensured accessibility to respondents in various countries and health systems, and expanded access to the survey ensured that not only “expert patients” (usually being cared for in “expert centres”) shared their views.

In summary, patients’ experiences of NTM-PD highlight important and unmet needs for better pharmacological treatment and education of medical staff.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: M. Shteinberg reports grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from GSK, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Kamada, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Teva, nonfinancial support from Actelion, grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from GSK, grants from Novartis, nonfinancial support from Rafa, and grants from Trudell Pharma, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: Jeanette Boyd is an employee of the European Lung Foundation.

Conflict of interest: S. Aliberti reports advisory fees and research support from Bayer Healthcare; speaker fees from Grifols; advisory fees from Astra Zeneca; advisory and speaker fees from Zambon; advisory and speaker fees, and research support from Chiesi and Insmed; advisory and speaker fees from GlaxoSmithKline; speaker fees from Menarini; advisory fees from ZetaCube Srl; and research support from Fisher & Paykel, all outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: E. Polverino has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Harris has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Berg has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Posthumus has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Ruddy has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: P. Goeminne has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Lloyd has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Alan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Altenburg has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Crossley has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Blasi reports a research grant and an advisory fee from AstraZeneca; a research grant from Bayer; research grants and advisory fees from Chiesi and GSK; advisory fees from Grifols, Guidotti and Insmed; a research grant and an advisory fee from Menarini; an advisory fee from Novartis; a research grant and an advisory fee from Pfizer; and advisory fees from Zambon and Vertex, all outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: J. Chalmers reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Gilead Sciences, grants and personal fees from Insmed, and personal fees from Novartis and Zambon, outside the submitted work.

Support statement: This study was supported by the European Respiratory Society EMBARC Clinical Research Collaboration. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Haworth CS, Banks J, Capstick T, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD). Thorax 2017; 72(Suppl 2): ii1–ii64. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abate G, Stapleton JT, Rouphael N, et al. Variability in the management of adults with pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Clin Infect Dis 2020; in press [ 10.1093/cid/ciaa252].doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa252]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Ingen J, Wagner D, Gallagher J, et al. Poor adherence to management guidelines in nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601855. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01855-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Zeenni N, Chanoine S, Recule C, et al. Are guidelines on the management of non-tuberculous mycobacteria lung infections respected and what are the consequences for patients? A French retrospective study from 2007 to 2014. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018; 37: 233–240. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3120-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkle E, Winthrop KL, Ranches GP, et al. Preliminary validation of the NTM Module: a patient-reported outcome measure for patients with pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901300. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01300-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung MW, Khoo E, Brode SK, et al. Health-related quality of life, comorbidities and mortality in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: a systematic review. Respirology 2016; 21: 1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/resp.12767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwak N, Kim SA, Choi SM, et al. Longitudinal changes in health-related quality of life according to clinical course among patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2020; 20: 126. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1165-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkle E, Aksamit T, Barker A, et al. Patient-Centered Research Priorities for Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM) Infection. An NTM Research Consortium Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: S379–S384. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-387WS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aliberti S, Polverino E, Chalmers JD, et al. The European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC): experiences from a successful ERS clinical research collaboration. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: 180–192. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02074-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers JD, Timothy A, Polverino E, et al. Patient participation in ERS guidelines and research projects: the EMBARC experience. Breathe (Sheff) 2017; 13: 194–207. doi: 10.1183/20734735.009517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shteinberg M, Crossley B, Lavie T, et al. Recommendations for travelling with bronchiectasis: a joint ELF/EMBARC/ERN-Lung collaboration. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00113-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00113-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalmers JD, Ringshausen FC, Harris B, et al. Cross-infection risk in patients with bronchiectasis: a position statement from the European Bronchiectasis Network (EMBARC), EMBARC/ELF patient advisory group and European Reference Network (ERN-Lung) Bronchiectasis Network. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1701937. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01937-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aliberti S, Masefield S, Polverino E, et al. Research priorities in bronchiectasis: a consensus statement from the EMBARC Clinical Research Collaboration. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 632–647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01888-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shteinberg M, Stein N, Adir Y, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and prognosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection among people with bronchiectasis: a population survey. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1702469. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02469-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aksamit TR, O'Donnell AE, Barker A, et al. Adult patients with bronchiectasis: a first look at the US bronchiectasis research registry. Chest 2017; 151: 982–992. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loebinger M, Loebinger M, Ringshausen F, et al. Characteristics of patients with pulmonary non-tuberculous Mycobacterial infection in bronchiectasis: data from the EMBARC registry. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: Suppl. 62, PA348. [Google Scholar]