Abstract

Objective

The controlling of the COVID-19 pandemic is influenced by the precautionary behavior of the community, and such behavior is frequently related to individuals’ risk perception. The current study aimed to explore risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in response to COVID-19.

Method

Qualitative in-depth interviews by telephone were undertaken with 26 participants from three affected cities in an initial stage of the disease outbreak, from May 3 to June 5, 2020. The method of analyzing data was inductive. The results were analyzed using interpretation, categorizing, and thematic analysis.

Results

The perception of risk is influenced by numerous individual, community, and cultural factors; these perceptions act as triggers for precautionary behavior, with a tendency to deny risks or react with exaggeration in terms of the precautionary reactions related to COVID-19. The thematic analysis produced two major categories: 1) risk perception and 2) precautionary behavior. The analysis provides essential insight into risk perception and precautionary behavior.

Conclusion

The risk perceptions and patterns of precautionary behavior could be unreliable, unhealthy, and culturally affected, which would influence the effectiveness of pandemic control measures. Further investigations with more data and including risk perception and precautionary behavior in the national response plan for emergency and crisis are highly recommended.

Practice implications

A greater understanding and ongoing assessment of COVID-19 risk perception could inform policymakers and health professionals who seek to promote precautionary behavior. This could also facilitate early interventions during pandemics.

Keywords: Prevention and control, Health behavior, Public health, Psychology of crisis, Community disasters

1. Introduction

Infectious diseases such as the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are among the major public health challenges. The COVID-19 epidemic exposed the fact that new human viruses will continue to emerge, which can have serious health consequences. COVID-19 made it clear how fast such diseases can expand universally and what the societal and economic impact can be [1].

International economies have been severely affected by the shutdown during the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, especially since April 2020 [[2], [3], [4]]. Most factories were closed, and many companies required government support to pay workers’ salaries or avoid a total collapse of their businesses [5,6]. Communities and employees realized this and understood the risks of gathering for work, parties, and weddings, and even within large families [7].

The risk perception of infectious disease is a key issue that affects the spread of the pandemic. To acquire accurate inferences and manage public health issues, epidemiological models should consider the assessments of risk perception [8]. Risk perceptions play a major role as predictors of precautionary behavior [9] and are among the major factors that must be considered and measured [10]. It is essential to assess behavioral responses to COVID-19 and determine how perceived risk could lead to engagement in protective behavior [11].

Individuals usually make many mistakes when assessing the risks of disease transmission [12,13]. They may be affected by mixed messages from several sources, such as the government, community, and media, and often receive misleading information from different media sources [14], such as social media, electronic newspapers, and WhatsApp groups.

Measuring the risk perception and understanding the determinants of a community’s resistance to protective measures against the spread of the coronavirus infection is fundamental for the effectiveness of social distancing public policies and minimizing non-adherence to the proposed precautionary controls [15].

Perceived risk must be understood as the vulnerability of a community and its ability to respond to a novel situation to mitigate potential effects [16]. According to Chatterjee et al. [17], risk awareness is the ideal method for preventing and slowing the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, engaging in precautionary behavior, such as wearing a facemask [18], washing one’s hands [19], and engaging in avoidance behavior or social distancing [20], is a key action for preventing and slowing COVID-19 infections. It is essential to understand the factors linked to such preventive behavior. Unexplainably, although billions have been invested in healthcare concerning infectious disease, rather little has been spent on investigating precautionary behavior as a predictor of the response to infectious disease outbreaks [1].

How people perceive risks and related behavior not only is associated with actual risks but also affects or leads to the reduced implementation of recommended preventive and precautionary behavior [21]. However, we still do not know much in Saudi Arabia about the complex relationships between people's awareness of the risks of infection with COVID-19. This study aimed to qualitatively examine COVID-19-related risk perceptions and their influence on precautionary behavior and adverse consequences from the perspective of Saudi communities living in affected areas.

2. Method

The current study was designed based on recommendations from earlier qualitative studies in Saudi Arabia [22,23]. A qualitative approach for capturing social and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic is the most recommended method [24].

2.1. Sample

Using a purposeful sampling method, 26 participants who met the inclusion criteria were asked to take part in a study about “Risk perceptions and precautionary behavior during COVID-19”. The inclusion criteria were as follows: [1] individuals living in the three most affected cities (Riyadh, Jeddah, and Al-Qatif) in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and during the time of the curfew [2]; individuals who voluntarily participated in the study; and [3] individuals aged ≥21 years old. They participated in telephone interviews from May 3 to June 5, 2020. The right to participate and confidentiality were assured. The interviews ranged from 40−60 min.

The interviews were based on a topic guideline developed from a literature search about “risk perceptions and precautionary behavior of the previous virus pandemics (i.e., ARS, H1N1, MERS)” and piloted with the first three participants (Appendix file1). The saturation method was reported in the current study, where no new themes were identified for the thematic categories or toward the theory [25].

2.2. Method of analyzing and ensuring the trustworthiness of the data

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyses were rooted in grounded theory; the thematic framework was derived inductively as it emerged from the data [26]. Rigor is the quality of being thorough and accurate while conducting qualitative studies [27]. The trustworthiness of the data, which is equal to the reliability and validity, was based on the work of Forero et al. [28], which was carried out by addressing credibility, transferability of the data, and dependability [29]. The current study applied the four-dimensions criteria (Table 1 ) to assess trustworthiness and enhance the credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of the findings. Credibility, for example, was achieved based on the experiences of the current researchers, who are health professionals who specialize in behavior change approaches and community health promotion, who are extensively familiar and competent with the healthcare setting and cultural context of the participants, and who have experience in team-based work. Through team-based working, and while the data was gathered, thick descriptions of the participants’ experience afforded transferability to other contexts. A sample of the transcribed individually were coded and categorized. Meanwhile, dependability was fostered by engaging more than one researcher directly in revising and categorizing the primary output of the interviews. Then, team-based data analysis ensured the confirmability of the findings, focusing on construction of the audit trail and the results clearly derived from the core of the data.

Table 1.

Rigor and the four-dimensions criteria to evaluate the trustworthiness of the current findings.

| Rigor Criteria (Equivalent quantitative criteria) | (Issue) Aim | (Question) Explanation | Technique applied in the current study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credibility (Internal validity) | (Truth value) To establish confidence and the ability of the study to capture what the research aimed to study, and that the results are true, credible, and believable. | (Have we really measured what we set out to measure?) The data was obtained in a dependable way that can be audited. | Credibility was enhanced by using thick description, while the data was gathered through individual interviews [48] and by providing a sample of the transcribed surveys to two qualitative data analysis experts, each of whom individually coded and categorized the data [17]. The interview guideline was piloted with the first three patients [22]. |

| Dependability (Reliability) | (Consistency) To ensure the findings are repeatable if the method were applied within the same cohort of participants, coders, and context. | (Would the current findings be repeated if the research were replicated in the same context with the same subject?) The consistency of the findings or the stability of the inquiry processes used over time. | Dependability was supported by engaging more than one researcher in the data analysis processes [49]. |

| Confirmability (Objectivity) | (Neutrality) To ensure that the data based on the participants’ narratives and words, and the findings, are shaped by participants rather than by a qualitative researcher. | (To what extent are our findings affected by personal interest and biases?) Neutralize the researcher’s influences. | The technique used to establish confirmability here is the audit trail, which details the current process of data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the data [50]. |

| Transferability (Generalizability or external validity) | (Applicability) To extend the degree to which the results can be applied to other situations or generalized to other contexts or settings. | (How applicable are the current findings to other subjects and other contexts?) Having the potential for the findings to be generalized to other settings. | A key factor in the transferability of the current study was the representativeness of the participants for that particular group and the input diversity and details [51]. Transferability of the data was improved through the development of rich descriptions in the interviews and the maintaining of detailed notes, to allow for a comparison and judgments about transferability to be made by the reader of this study with other studies conducted in similar contexts [17]. |

3. Result

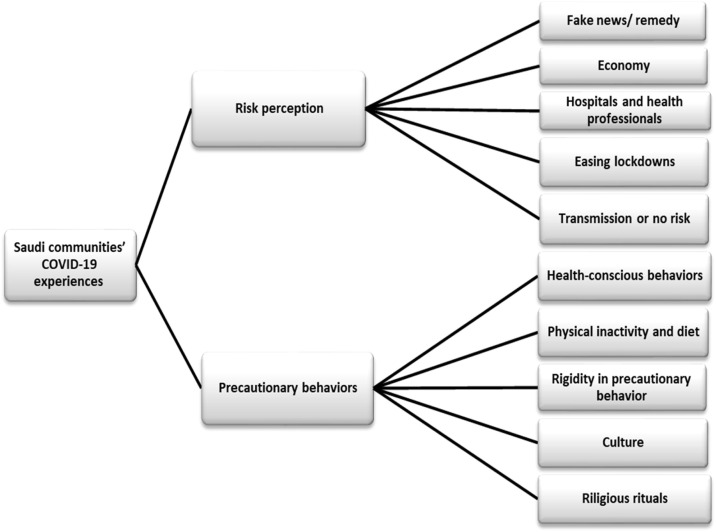

The thematic analysis produced two major categories: risk perception and precautionary behavior (see Fig. 1 ). The risk perception category includes five subthemes: 1) Fake news/remedy, 2) Economy, 3) Hospitals and health professionals, 4), Easing lockdowns, and 5) Transmission or no risk. The precautionary behavior category also includes five subthemes: 1) Health-conscious behavior, 2) Physical inactivity and diet, 3) Rigidity in precautionary behavior, 4) Culture, and 5) Religious rituals. Table 2 shows the sample demographic information and characteristics of participants (N = 26).

Fig. 1.

Selective coding of axial groups: communities’ COVID-19 experiences.

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics.

| N 26 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 21−29 | 5 (19.2) |

| 30−39 | 7 (23.1) | |

| 40−49 | 11 (42.3) | |

| ≥ 50 | 3 (11.5) | |

| Gender | Male | 17 (65.4) |

| Female | 9 (34.6) | |

| Education | Elementary & middle school | 2 (7.7) |

| High school | 4 (15.4) | |

| University | 14 (53.8) | |

| Postgraduate | 6 (23.1) | |

| Marital status | Single | 4 (15.4)) |

| Married | 19 (73.1) | |

| Other | 3 (11.5) | |

| Experience of being diagnosed with COVID-19 | Yourself | 0 (0.0) |

| One of your family | 2 (7.7) | |

| One of your relatives | 2 (7.7) | |

| One of your colleagues | 3 (11.5) | |

| Another person you know well | 5 (19.2) | |

| None | 14 (53.8) | |

| Have chronic diseases | Diabetes | 3 (11.5) |

| Blood pressure | 2 (7.7) | |

| Lung and respiratory diseases | 1 (3.8) | |

| Obesity | 1 (3.8) | |

| Other | 1 (3.8) | |

| None | 18 (69.2) | |

| One of your family (at your home) has chronic diseases | Diabetes | 2 (7.7) |

| Blood pressure | 2 (7.7) | |

| Obesity | 1 (3.8) | |

| Stroke | 1 (3.8) | |

| Other | 1 (3.8) | |

| None | 19 (73.1) | |

3.1. Risk perception

3.1.1. Risk perception of fake news and remedies regarding COVID-19

One major risk is unreliable and false information regarding COVID-19, including spreading false news about COVID-19 in the area, which makes this disinformation and misinformation about COVID-19 as dangerous as the virus itself. The main official sources of COVID-19 information are the Ministry of Health daily reports. Despite that, it seems as though people go beyond the official statistical report to find the worst scenarios.

“… the death numbers are not really as in their official report, I am really worried that the numbers are double or more. I search the internet to have more details about COVID-19 death… I then knew that the number is much more!” (P.6)

As a psychological coping mechanism generated by the coronavirus, some individuals cling to a shred of hope about unreliable information to feel safe, even if this information is fake.

“I joined a WhatsApp group about the alternative treatments for COVID-19. It is a useful group with very rich and practical information… really, it is much better than your official information…” (P.7)

Digital communications could help bridge the gap between social distancing and physical distancing measures.

“… frankly, WhatsApp helped me stay connected with my friends and relatives during the virus pandemic… it provides us with good information.” (P.2)

WhatsApp rumors became contradictory and worsened more than ever.

“WhatsApp treatment rumors are annoying me! I heard something different about COVID-19… but at the beginning of the virus, I feel good when hearing only good information which easiest the issue and I followed their treatment recommendations… they suggested a cultural and traditional treatment.” (P.21)

3.1.2. Economic risk during COVID-19

Connections between economic stress and health related to COVID-19 were obvious in the participants' perceptions.

“Don’t believe the media!… we exaggerate the matter, it is an economic game!… some governments around the world have purposefully overreacted to the COVID-19 pandemic…” (P.3)

Some people perceived the economic risk as being more significant than health issues. Lockdowns due to COVID-19 have costs of an unknown magnitude.

“… people around the world die from recessions more than by COIVD-19… independent international news confirmed this… the matter here is about choice; [with a] healthy economy then we will have our goal of having a healthy community… but not the opposite.” (P.16)

3.1.3. Risk at hospitals and from health professionals

Health professionals caring for COVID-19 patients face separation from families. They also face a health stigma. Their families could be perceived as a main source of COVID-19.

“Some people tend to avoid going to their routine clinics in order to avoid meeting people there… you knew it as a sick place rather than as a place for sick people…” (P.11)

Participants said that they would not visit the hospital if they got sick. Rather, they would buy medicine from the nearest pharmacy.

“…I will not go to my clinics… the pharmacy could be my choice [as] it is safer…” (P.25)

Health professionals face further challenges, including being stigmatized by the general public or being seen as a source of risks.

“My nephew works in a medical laboratory at the main hospital [and] our family is concerned that he will bring this virus to us from his work…” (P.5)

People with chronic diseases such as diabetes or high blood pressure, and those who live with these people, showed more alertness to being at risk of COVID-19 infection (Table 3 ). This perception was mixed with a kind of stigma.

“My youngest brother is a doctor; he works among the frontline of health professionals at the hospital… It's devastatingly stressful to me to see my brother go home and back… I am diabetic and my parents are old…” (P.8)

Table 3.

Perception of risk and precautionary behavior engaged in by the sample (n = 26).

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Riskiest places | Social occasions (i.e., parties, weddings, funerals) | 24 (92.3) |

| Hospitals and clinics | 20 (76.9) | |

| Restaurants, shopping, and entertainment (crowded places) | 20 (76.9) | |

| Religious mass gatherings (Hajj and Umrah) | 18 (69.2) | |

| Work/schools | 17 (654) | |

| Mosques | 13 (50.0) | |

| Other | 2 (7.7) | |

| Precautionary behavior | Stay home (precautionary social distancing measure) | 25 (96.2) |

| Wear face mask | 22 (84.6) | |

| Avoid social activities | 22 (84.6) | |

| Avoid shaking hands, hugging, or kissing people as part of a cultural greeting | 19 (73.1) | |

| Take a cultural/herbal supplement and diet | 15 (58.0) | |

| Avoid visiting doctors and clinics | 15 (58.0) | |

| Be absent from work/school (for myself/my children) | 13 (50.0) | |

| Sanitize, clean, and disinfect | 13 (50.0) | |

| Avoid crowded places | 12 (46,2) | |

| Other | 2 (7.7) |

3.1.4. Risk and easing the coronavirus lockdown

Participants were divided between those who wanted to ease or end the lockdown and those who wanted to extend it.

“I think the main problem nowadays came from our teenagers and some careless people. When I go out for a walk or to run errands, these individuals no longer follow the COVID-19 instructions! After the curfew was suspended, they thought the risk was over.” (P.5)

The other opinion was against the lockdown. Psychological sounds were more prevalent in the participants’ opinions.

“Easing the lockdown came at a time where I was at the edge! I started feeling down, angry, and other mental issues… I will not be a survivor if they re-lockdown.” (P.12)

Some people could see this easing as a sign of a low risk of getting sick and did not feel that they had to follow recommended precautionary instructions.

“The curfew being lifted does not mean that we are risk-free! See, here people forget all of that! Crowding here… no facemask…” (P.26)

3.1.5. Risk of transmission or no risk

People saw one side of COVID transmission, as they observed the risk of being affected by others but not being transmitters themselves.

“I won’t transfer the virus as I am free from this risk… so I am now not wearing a facemask…” (P.3)

According to other participants, facemasks may meaningfully minimize the transmission of COVID-19 and lower peak hospitalizations.

“…wearing a facemask in public is a must, mainly in crowded places, to protect yourself and others from possible infection…” (P.15)

Risk perception affects people's behavior and attitudes. These perceptions are influenced by previous individual experiences.

“Why do people tend to exaggerate the danger of COVID-19? Comparing it to one we already knew, like MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome)… Why now do we complicate the situation… do you remember that old man who kissed his camel?… O’ man, we need to calm down…” (P.16)

3.2. Precautionary behavior

3.2.1. Health-conscious behavior

Individuals in our study followed health-conscious behavior that included understanding and obeying the government mandate for social distancing.

“…we should stay home, and under that emergency circumstances, if we go outside the home, we must stay away from crowded places, as much as possible… using gloves and face masks.” (P.12)

The easy spread of COVID-19 forced people to wear a mask and use gloves as the first precautionary route.

“…always, I keep myself safe by wearing a mask all the time and whenever I go outside I keep sanitizing my hands.” (P.1)

When they became exposed to COVID-19, they voluntarily entered self-quarantine.

“…during the first week of people starting to talk about COVID-19, I heard that one of my colleagues at the same office in my work had corona… then my boss sent me a message… then he phoned me about this… I immediately entered 14-day self-quarantine… voluntarily.” (P.15)

3.2.2. Physical inactivity and diet program

The dramatic decrease in daily physical activity due to the complete lockdown is likely among the most common types of precautionary behavior.

“School closures, working remote, physical distancing, it's too much negativity for anyone… I encourage my family to do at least 40 min of physical activities per day…” (P.4)

Engaging in some form of indoor physical activity is another viable solution for some.

“We created indoor physical activities that were fun and easy, during lockdown… those physical activities can contribute to making kids happier and release their negative energy…” (P.22)

The COVID-19 epidemic has had an impact on eating habits and eating behavior.

“Social distancing protects us from COVID-19 at the main side, but the hidden side is that we ate more with less exercise…” (P.25)

It seems that the participants engaged in a kind of diet program as a precautionary action in the face of COVID-19.

“Drinking a lot of fresh juices, garlic, onion seeds, and honey that, mixed together, will help protect against COVID-19… you know healthy foods help to boost the immune system.” (P.6)

3.2.3. Rigidity of precautionary behavior

Strict precautionary behavior may provide disadvantageous reactions and unhealthy responses.

“…now and for more than three months my children have not been outside our home… they have sufficient indoor activities…” (P.10)

The harshness of precautionary behavior could be extended outside of the healthy target.

“I will never, ever send my children to their school if it is opened next year, it is risky!… they can study at home or attend the distance-learning classes...” (P.24)

The precautionary reactions could be unhealthy behavior, like appointment nonadherence.

“I had a heart attack before about three years ago and I am a diabetes patient as well… I missed four follow-up clinics with my doctor…” (P.25)

3.2.4. Culture and gatherings

Perceptions about facemask use came down to cultural norms about covering the face, which women usually do more often than men.

“…Covering the face is for women, some people felt ashamed to wear face masks at the beginning against government directives and medical advice…” (P.17)

It seems that females might adhere to the lockdown to a greater extent than males.

“…as you can see, we stay home and wear hijab with a facemask, not only facemask, but the problems came from our men, as they refuse to stay home…” (P.14)

Some men among our participants confirmed that culture has the upper hand in determining their behavior and reaction.

“…staying at home and covering the face is not for men in our culture…” (P.23)

Who would win: culture or science? The risks of social gatherings during holiday celebrations like Ramadan and Eid, which was in the middle of the COVID-19 curfew (May), were challenging for the Saudi community.

“Our society finds it very tough to avoid some social activities… social distancing will not be the first choice even for me, mainly when the Eid comes…” (P.13)

Eid prayers at the grand mosques, visiting family members, exchanging gifts, and spending time at big family parties are common traditions for Saudis during Eid.

“Eid al-Fitr traditionally means that we have to visit our extended family, gathering with relatives... However, with COVID-19, large gatherings are no longer safe…” (P.4)

3.2.5. Religious rituals

COVID-19 affected the cultural schedule, forcing cancellations and suspensions of some of society’s biggest cultural events and activities.

“Private prayer in my home was a difficult decision for me and for most of the community here, mainly when Ramadan started…. my soul was ill at Ramadan mainly…” (P.20)

As strict measures against the COVID-19 outbreak are slowly eased, mosques are reopening for daily prayers.

“After opening our mosque for prayers, you know two months after prayers were suspended at mosques, I have started praying cautiously, trying to keep my spirit alive…” (P.2)

3.3. Discussion

This investigation is one of the first Arabic studies conducted in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and during the time of the curfew. The current results showed the importance of understanding the community’s risk perception, looking at the role of precautionary behavior, and summarizing the lessons for responding to any future COVID-19-like situations.

The qualitative method may play a major role in understanding community responses and effective solutions and strategies during epidemics like COVID-19 [30]. It has been recommended that health information be gathered from different sources in communities and by different methods [31]. Because the qualitative findings could gather health data directly from its source, frequently it has been mixed with quantitative health information in order to incorporate and obtain a richer picture of health information behavior [32] and to identify community-specific health demands tailored to the needs of that specific community [33].

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) posits that during a new pandemic, obtaining proper information from official sources and dealing with risk perceptions can increase people’s awareness of convenient precautionary behavior and, consequently, their adoption of preventive measures [34].

Our findings align with several studies from other countries and those addressing previous influenza diseases [[35], [36], [37], [38]]. Causal links between risk perception related to COVID-19 and precautionary behavior are not always sufficient to cause people to obey recommended preventative behavior [24].

During the previous influenza virus pandemic (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia, individuals who were known for their deep love for camels denied the relationship between camels and MERS-CoV, launching the hashtag “Kiss Your Camel,” which became popular on social media in 2015. The risk of the emergence of COVID-19 within the same community and with the same social media would be critical and a burden to the healthcare infrastructure [39]. It is common in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere to find a group of people, mainly in rural areas, who prefer to seek the help of cultural healers instead of following the guidelines of health care professionals, which heightens the risk of transmission. Therefore, it is recommended to mobilize existing health resources to reach out to rural health collaborators and provide materials and skills for at-risk communities [40]. It is also recommended that effective strategies and successful COVID-19 containment procedures be implemented to enhance operation readiness based on practicing precautionary measures and mobilizing human resources, as well as medical equipment. This is necessary for successful COVID-19 containment [41].

The model of crisis and emergency risk communication indicates that it is essential to know the community risk perception and the sources of information that they credit to authorize functional communication and the framing of key messages. Such messages must be evidence-based, respond to misinformation, and induce rational, precautionary behavior [42,43]. Some participants in the current findings expressed more concern about the present economic downturn, such as job losses, than about COVID-19 as a health threat. Understanding how risk perception and certain types of precautionary behavior might affect the course of the influenza pandemic, and what its potential psychological, social, and economic impacts would be, will help decision-makers give appropriate advice [1,44].

Here, more attention must be paid to psychological and cultural factors influencing the risk perceptions, such as the tendency to deny risks or the fact that unhealthy behavior is related to avoiding threatening/official information about COVID-19 [45]. Thus, during a pandemic, psychological responses to health risks could lead to increased negative emotional expressions such as anger or denial, which are coping strategies to gain a psychological risk reduction [46,47]. All emerging infectious disease pandemic plans should include a psychological safety plan with a framework containing clear cultural and religious considerations that align with communities’ norms [48].

Individuals who perceived themselves as being at risk for COVID-19 could engage in precautionary behavior, while at the same time stigmatizing those whom they perceived as being possible sources of infection [49]. Surprisingly, healthcare professionals and their families are among those who have been stigmatized and accused of being the main sources of COVID-19 infection. Such a perception is critical when healthcare professionals who are fighting this battle on behalf of communities encounter stigma and a loss of trust among their communities [50].

Gender differences in social distancing practices appear to be associated with cultural behavior. Recent Arabic results confirmed that women are more likely to endorse social distancing and precautionary behavior than men during the COVID-19 pandemic [51].

As has been illustrated in a recent study in ten countries around the world, showed that many socio-cultural factors affect the way in which people perceive risk of COVID-19 [52]. In fact, a small cultural consideration can enhance the management of emergency response [53]. Saudi authorities continue to report that one major reason for the increasing cases is crowded social gatherings that violated the official health advice and commands. Cultural/social gatherings of more than 50 people are prohibited, and violators are subject to fines [54]. A specific regulation was added during the Eid curfew/lockdown enforcement [55]. Hajj and Umrahs are religious mass gatherings that are estimated to produce serious challenges in terms of mass-level exposures and the spread of COVID-19, not only in Saudi Arabia but in every corner of the world [56,57]. Therefore, the government made the very reasonable decision to make the Hajj of this year open to only a very low number of pilgrims.

3.4. Conclusion

The current results regarding risk perceptions and precautionary behavior, as reported by the study participants, have a positive consequence for implementing public health during the COVID-19 pandemic and will help improve the understanding of emerging infectious diseases among our culture and communities in the future.

Finally, due to the characteristics of qualitative methods, the sample size of this study is limited in terms of applying the purposive sampling technique. Future researchers should address the risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in Saudi Arabia quantitatively with a randomized sample.

3.5. Practice implications

Measuring to control the COVID-19 pandemic involves not only developing vaccines and launching adequate interventions but also appropriately informing the community about risks and health precautions. This finding suggests that policymakers must pay more attention to the roles of risk perception and precautionary behavior during infectious disease outbreaks.

Authors’ contributions

M.M. devised the idea for the study. M.M, B.A., and F.H. collected and analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. All authors were involved in interpreting the results of the analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. N.S. contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. The final version was approved by all authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee at King Khalid University (Ed-KKU) approved this study. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

This work did not receive any funding.

Participant data

This manuscript report data on patients with COVID-19, and this work confirms that this data has not been reported in any other submission by the authors or anyone else.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants for their interest and willingness to contribute to the study. We extend our heartfelt thanks to all the healthcare professionals who helped us recruit participants.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.02.025.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Smith R.D. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Social Sci. Med. 2006;63:3113–3123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dang A.K., Le X.T.T., Le H.T., Tran B.X., Do T.T.T., Phan H.T.B., et al. Evidence of COVID-19 impacts on occupations during the first Vietnamese national lockdown. Ann. Global Health. 2020;86(1) doi: 10.5334/aogh.2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L., et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran B.X., Vu G.T., Latkin C.A., Pham H.Q., Phan H.T., Le H.T., Ho R.C. Characterize health and economic vulnerabilities of workers to control the emergence of COVID-19 in an industrial zone in Vietnam. Saf. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habel J., Jarotschkin V., Schmitz B., Eggert A., Plötner O. Industrial buying during the coronavirus pandemic: a cross-cultural study. Ind. Mark. Manage. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortez R.M., Johnston W.J. The coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind. Mark. Manage. 2020;88:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuevas E. An agent-based model to evaluate the COVID-19 transmission risks in facilities. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahin M.A.H., Hussien R.M. Risk perception regarding the COVID-19 outbreak among the general population: a comparative Middle East survey. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry. 2020;27(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slovic P. Perception of risk. Science. 1987;236:280–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3563507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girma S., Agenagnew L., Beressa G., Tesfaye Y., Alenko A. Risk perception and precautionary health behavior toward COVID-19 among health professionals working in selected public university hospitals in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241101. e0241101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wise T., Zbozinek T.D., Michelini G., Hagan C.C., Mobbs D. 2020. Changes in Risk Perception and Protective Behavior During the First Week of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States.https://osf.io/dz428 Preprint at PsyArXiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho H., Lee J.S., Lee S. Optimistic bias about H1N1 flu: testing the links between risk communication, optimistic bias, and self-protection behavior. Health Commun. 2013;28:146–158. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.664805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., Short M.B., Sledge D., Tita G.E., et al. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. J. Criminal Justice. 2020:101692. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sha H., Hasan M.A., Mohler G., Brantingham P.J. Dynamic topic modeling of the COVID-19 Twitter narrative among US governors and cabinet executives. arXiv. 2020 preprint arXiv:2004.11692. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa M.F. Health belief model for coronavirus infection risk determinants. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2020;54:47. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de León-Martínez L.D., Palacios-Ramírez A., Rodriguez-Aguilar M., Flores-Ramírez R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatterjee R., Bajwa S., Dwivedi D., Kanji R., Ahammed M., Shaw R. COVID-19 risk assessment tool: dual application of risk communication and risk governance. Progress Disaster Sci. 2020:100109. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C., Chudzicka-Czupała A., Grabowski D., Pan R., Adamus K., Wan X., et al. The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:901. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. S0889-1591(20)30511-0. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran B.X., Nguyen H.T., Le H.T., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the Vietnamese during the national social distancing. Front Psychol. 2020;11(Sep):565153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565153. PMID: 33041928; PMCID: PMC7518066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin G.J., Amlôt R., Page L., Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behavior change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651. b2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alqahtani M.M. Understanding autism in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative analysis of the community and cultural context. J. Pediatric Neurol. 2012;10:015–022. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alqahtani M.M., Holmes T., Al-Rammah T.Y., Alqahtani K.M., Al Tamimi N., Alhrbi F.H., et al. Are we meeting cancer patient needs? Complementary and alternative medicine use among Saudi cancer patients: a qualitative study of patients and healthcare professionals’ views. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2018;24:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teti M., Schatz E., Liebenberg L. 2020. Methods in the Time of COVID-19: The Vital Role of Qualitative Inquiries. 1609406920920962. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker J.S. The use of saturation in qualitative research. Can. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2012;22:37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser B.G. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965;12:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cypress B.S. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2017;36:253–263. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forero R., Nahidi S., De Costa J., Mohsin M., Fitzgerald G., Gibson N., et al. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Services Res. 2018;18:120. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinkovics R.R., Penz E., Ghauri P.N. Enhancing the trustworthiness of qualitative research in international business. Manage. Int. Rev. 2008;48:689–714. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Weerd W., Timmermans D.R., Beaujean D.J., Oudhoff J., van Steenbergen J.E. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:575. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran B.X., Dang A.K., Thai P.K., Le H.T., Le X.T.T., Do T.T.T., et al. Coverage of health information by different sources in communities: implication for COVID-19 epidemic response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(10):3577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh S., Costello K.L., Chen A.T., Wildemuth B.M. Qualitative methods for studying health information behaviors. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016;53(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le H.T., Nguyen D.N., Beydoun A.S., Le X.T.T., Nguyen Q.T., Pham Q.T., Ta N.T.K., Nguyen Q.T., Nguyen A.N., Hoang M.T., Vu L.G., Tran B.X., Latkin C.A., Ho C.S.H., Ho R.C.M. Demand for health information on COVID-19 among Vietnamese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(Jun (12)):E4377. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124377. PMID: 32570819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry M., Al Amri M., Memish Z.A. COVID-19 in the shadows of MERS-CoV in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Epidemiol. Global Health. 2020;10:1–3. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.200218.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanciano T., Graziano G., Curci A., Costadura S., Monaco A. Risk perceptions and psychological effects during the Italian COVID-19 emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:2434. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honarvar B., Lankarani K.B., Kharmandar A., Shaygani F., Zahedroozgar M., Haghighi M.R.R., et al. Knowledge, attitudes, risk perceptions, and practices of adults toward COVID-19: a population and field-based study from Iran. Int. J. Public Health. 2020;65(6):731–739. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01406-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quandt S.A., LaMonto N.J., Mora D.C., Talton J.W., Laurienti P.J., Arcury T.A. COVID-19 pandemic among Latinx farmworker and nonfarmworker families in North Carolina: knowledge, risk perceptions, and preventive behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(16):5786. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dryhurst S., Schneider C.R., Kerr J., Freeman A.L., Recchia G., Van Der Bles A.M., et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alamro N., Almana L., Alabduljabbar A., Alshunaifi A., AlKahtani M., AlDihan R., et al. 2020. COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO) Saudi Arabia–Wave 1. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran B.X., Phan H.T., Nguyen T.P.T., et al. Reaching further by village health collaborators: the informal health taskforce of Vietnam for COVID-19 responses. J. Glob. Health. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tran B.X., Hoang M.T., Pham H.Q., Hoang C.L., Le H.T., Latkin C.A., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. The operational readiness capacities of the grassroots health system in responses to epidemics: implications for COVID-19 control in Vietnam. J. Glob Health. 2020;10(Jun (1)) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.011006. PMID: 32566168; PMCID: PMC7294390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wise T., Zbozinek T.D., Michelini G., Hagan C.C. 2020. Changes in Risk Perception and Protective Behavior During the First Week of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blendon R.J., Benson J.M., DesRoches C.M., Raleigh E., Taylor-Clark K. The public’s response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:925–931. doi: 10.1086/382355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khosravi M. Perceived risk of COVID-19 pandemic: the role of public worry and trust. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2020;2020(17) em203. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaughan E., Tinker T. Effective health risk communication about pandemic influenza for vulnerable populations. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:S324–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang L., Li Y., Hu S., Chen M., Yang C., Yang B.X., et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lateef F. Face to face with coronavirus disease 19: maintaining motivation, psychological safety, and wellness. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock. 2020;13:116. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_27_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alqahtani M.M., Salmon P. Cultural influences in the aetiological beliefs of Saudi Arabian primary care patients about their symptoms: the association of religious and psychological beliefs. J. Religion Health. 2008;47:302–313. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brug J., Aro A.R., Oenema A., De Zwart O., Richardus J.H., Bishop G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:1486. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz J., King C.C., Yen M.Y. Protecting healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: lessons from Taiwan’s severe acute respiratory syndrome response. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdelrahman M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of Arab residents of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00352-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dryhurst S., Schneider C.R., Kerr J., Freeman A.L., Recchia G., Van Der Bles A.M., et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergeron W.P. Considering culture in evacuation planning and consequence management. J. Emerg. Manage. (Weston, Mass.) 2015;13:87–92. doi: 10.5055/jem.2015.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Algaissi A.A., Alharbi N.K., Hassanain M., Hashem A.M. Preparedness and response to COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: building on MERS experience. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Memish Z.A. COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean region and Saudi Arabia: prevention and therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yezli S., Khan A. COVID-19 social distancing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: bold measures in the face of political, economic, social and religious challenges. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atique Suleman, Itumalla Ramaiah. Hajj in the time of COVID-19. Infect. Dis. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.