Dear Editor,

Since the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies to minimize nosocomial transmission have taken center‐stage. 1 There are increasing reports documenting the high infection rates in healthcare workers (HCWs). 2 , 3 A recent finding 4 was that hospital administrative personnel showed higher infection rates than frontline HCWs, indicating the inadequacy of IPC trainings for administrative staff. Furthermore, Chu et al 5 revealed that over 70% of nosocomial infections occurred in HCWs not assigned to frontline departments during the epidemic. Shortages in personal protective equipment (PPE) could have led to this, but we wanted to investigate if the lack of awareness regarding IPC practices in nonfrontline HCWs was also a contributing factor. In China, most hospitals routinely conduct IPC trainings for HCWs, but it is difficult to evaluate whether these trainings adequately prepare staff to respond to emergencies. Therefore, we conducted a survey to investigate if HCWs were sufficiently knowledgeable about IPC practices and adequately trained in emergency pandemic response.

In April 2020, 236 self‐administered questionnaires (Appendix S1) were distributed to eight hospitals designated for managing COVID‐19 patients in Hubei Province, China. The questionnaire surveyed the knowledge of HCWs, training frequency, and adherence to IPC policies under different settings: preoutbreak, postoutbreak/prefrontline deployment, and postfrontline deployment. Individual scores were recorded on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 indicating superior knowledge and compliance. We also asked participants which setting from among simulations, tests, self‐study, training videos, practical experience, and didactic lectures, provided the most useful training for an emergency pandemic response. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS using paired t test and Tamhane T2 test (P < .05).

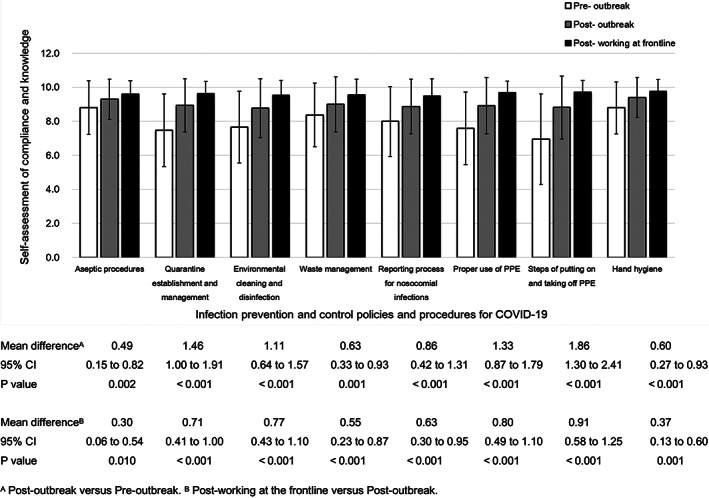

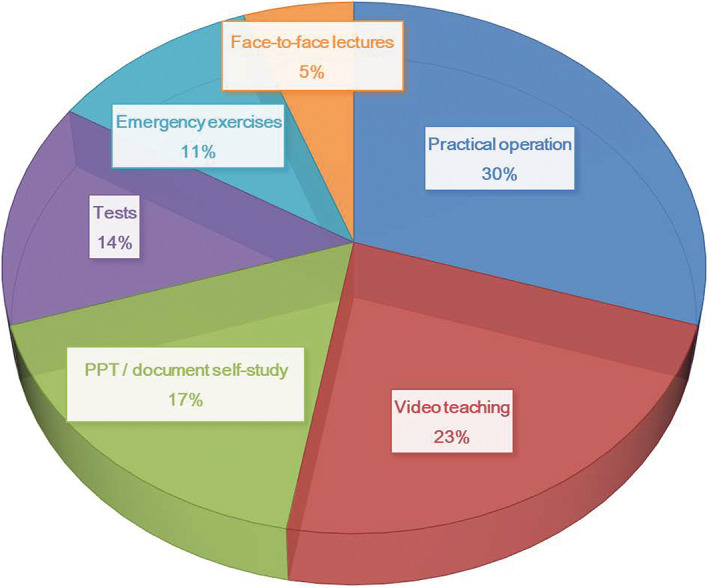

197 HCWs (response rate 83.5%) from different nonfrontline departments (Dermatology‐27.9%; Surgery‐22.8%; Internal Medicine‐20.8%; etc.) completed the questionnaire (Table 1). Between late December 2019, and early April 2020, IPC trainings were organized more than twice as frequently as usual (6.34 ± 5.02 vs 2.67 ± 2.41, P < .001); or every 14.20 days. Compliance with and knowledge of IPC practices improved significantly postoutbreak (total score, 72.06 ± 11.17) compared with preoutbreak (63.72 ± 13.44), and after working at the frontline (77.07 ± 5.36). These trends were observed to varying degrees across all the categories of IPC policies and procedures (Figure 1). Of note, the biggest improvement in scores was in knowledge regarding the correct donning and doffing procedures for PPE (A: 1.86; 95%CI, 1.30‐2.41; P < .001. B: 0.91; 95%CI, 0.58‐1.25; P < .001). In addition, the majority of HCWs (30%) considered field experience to be the most beneficial form of training among the various training settings. However, traditional forms of IPC training, such as didactic lectures (5%) and written tests (14%) were not deemed to be very useful by the HCWs (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Departmental proportion of nonfrontline medical staff

| Involved departments | Participants (N = 197), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Dermatology | 55 (27.9) |

| Surgery | 45 (22.8) |

| Internal medicine | 41 (20.8) |

| Gynecology and obstetrics | 18 (9.1) |

| Pediatrics | 8 (4.1) |

| Ophthalmology and Otorhinolaryngology | 7 (3.6) |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 5 (2.5) |

| Others a | 18 (9.1) |

Referring to Departments of Stomatology, Geriatrics, Anesthesiology, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ultrasonics, Oncology, Pharmacy and Laboratory Medicine.

FIGURE 1.

Knowledge of infection‐control and prevention strategies and compliance in HCWs across three settings

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of HCWs reporting each setting to be the most beneficial for infection‐control trainings

In response to the outbreak, healthcare facilities in China are actively conducting IPC trainings of staff to ensure robust compliance with policies, therefore contributing to the enhancement of postoutbreak IPC awareness. Our study suggested that nonfrontline HCWs' knowledge regarding proper use of PPE and protocols for quarantine and isolation zones need further improvement. In the future, nonfrontline HCWs should be trained adequately in relevant knowledge and skills, 6 such that they may safely engage in clinical duties during current and future pandemics. Though the retrospective and subjective nature of our study are its limitations, we learned some important insights. Practical experience at the frontlines resulted in significant improvements in knowledge regarding prevention strategies, highlighting the benefit of clinical practice in raising awareness. Furthermore, HCWs reported practical experience to be of great benefit in improving compliance; lending support to the role of field training in the preparedness of HCWs' emergency response to pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Juan Tao and Yan Li conceptualized the study. Liu Yang and Mahin Alamgir drafted the initial manuscript. Qing Wang, Jingjiang Cao, Jianxiu Wang, and Han Liu collected the data and Xiaoxu Yin conducted the data analysis. All authors contributed to revisions of the initial manuscript.

Supporting information

APPENDIX S1: Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by HUST COVID‐19 Rapid Response Call Program (2020kfyXGYJ056) and Hubei Provincial Emergency Science and Technology Program for COVID‐19 (2020FCA037).

Liu Yang and Mahin Alamgir have contributed equally to this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoV‐IPC‐2020.4. Accessed 8 September 2020.

- 2. World Health Organization . Report of the WHO‐China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. Accessed 8 September 2020.

- 3. Anelli F, Leoni G, Monaco R, et al. Italian doctors call for protecting healthcare workers and boosting community surveillance during covid‐19 outbreak. BMJ. 2020;368:m1254 10.1136/bmj.m1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maltezou HC, Dedoukou X, Tseroni M, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in healthcare personnel with high‐risk occupational exposure: evaluation of seven‐day exclusion from work policy. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa888 10.1093/cid/ciaa888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chu J, Yang N, Wei Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 54 medical staff with COVID‐19: a retrospective study in a single center in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1‐7. 10.1002/jmv.25793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gagneux‐Brunon A, Pelissier C, Gagnaire J, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: advocacy for training and social distancing in healthcare settings. J Hosp Infec. 2020;106(3):610‐612. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

APPENDIX S1: Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.