Abstract

COVID-19 pathology is mainly associated to a pulmonary disease which sometimes might result in an uncontrollable storm related to inflammatory diseases which could be fatal. It is well known that phosphodiesterase enzyme type 5 inhibitors (PDE5Is), such as sildenafil, have been successfully developed for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension; interestingly, more recently, it was shown that PDE5Is might be also anti-inflammatory. Therefore, it would be of interest to question about the use of PDE5Is to overcome the COVID-19 storm, as much as PDE5 is mainly present in the lung tissues and vessels.

Keywords: Acute lung injury, COVID-19, nucleotide phosphodiesterase enzyme

BACKGROUND

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus (nCoV) was appeared in Wuhan city of China, named 2019-nCoV, leading to coronavirus infection disease (COVID-19), which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). On January 20, 2020, the World Health Organization affirmed and declared the COVID-19 outbreak as an international health emergency, which was regarded as an epidemic on March 11, 2020.[1]

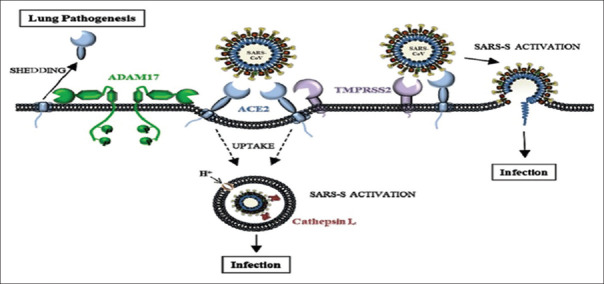

CoV is an enveloped positive-sense, single-strand RNA virus, which is the largest one among other RNA viruses from Coronaviridae family. CoV has three imperative proteins in its structure, which are membrane protein, spike protein, and nucleocapsid protein. These structural proteins are involved in the viral pathogenesis and regarded as targets for different experimental antiviral agents [Figure 1].[2]

Figure 1.

Genomic structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Previously, human CoV (HCoV-OC43) and HCoV-229E were the only known coronaviruses, as HCoV-OC43 was isolated in 1967 from volunteers with the common cold in the United Kingdom. The analysis of genome sequences proposed that HCoV-OC43 was originated from bovine, so-called bovine CoV.[3] 2019-nCoV is a betacoronavirus which is officially known as SARS-CoV-2, which has about 80% nucleotide similarity with SARS-CoV.[4]

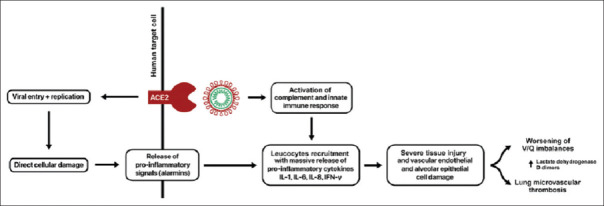

Amide different recent researches, the entry point of SARS-CoV-2 is through angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2), which is highly expressed in the alveolar pulmonary cells, renal proximal tubules, and vascular endothelium. Besides, different peptides and comediators such as bradykinin, plasmin, and transmembrane serine protease may modulate the affinity and binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 [Figure 2].[5]

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Horn et al. found that patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PHT) are at a higher risk for COVID-19-induced adverse outcomes and complications. Since infection with SARS-CoV-2 is linked with cardiovascular complications and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[6]

Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase enzyme (PDE) plays a major role in intracellular signaling by controlling beyond receptors' cellular responses.[7] Their specific PDE inhibitors (PDEIs) are drugs that overcome the hydrolytic inactivation of intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in their respective 5' nucleotide. There are two types of PDEIs, nonspecific (theophylline, aminophylline, and pentoxifylline) and specific (nimodipine, rolipram, cilostazol, and sildenafil).[8] There are 11 subtypes of PDE family, however PDE4 is the chief cAMP-metabolizing enzyme found in the immune and inflammatory cells. Therefore, PDE4 inhibitors have been proven as anti-inflammatory agents against different pulmonary disorders through inhibiting the release of inflammatory signals and cytokines.[9] As well, all types of PDE type 5 inhibitors (PDE5Is) increase the level of nitric oxide (NO), which has potent antiviral effects, reducing the migration of polymorphonuclears, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and associated acute lung injury (ALI).[10]

In COVID-19, there is a high interleukin-6 (IL-6) serum level with a reduction of NO level; therefore, PDE5 inhibitors like sildenafil may be used in the management of COVID-19 since they inhibit other types of coronavirus.[11]

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to review the possible role of PDE5 inhibitors in the management of COVID-19 patients.

SEARCH STRATEGY

As a general rule, an endeavor of this study article was to present a minireview concerning the potential effect of PDE5Is. Evidence from experimental, preclinical, and clinical studies was appraised as minireview.

An array of search strategies was assumed that included electronic database searches of Scopus, Web of Science, Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and PubMed using MeSH terms, keywords, and title words during the search. The terms used for these searches were as follows: (PDE5Is OR sildenafil OR tadalafil) AND (Acute lung injury OR ARDS). (PDE5Is OR sildenafil OR tadalafil) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2). (PDEIs) AND (COVID-19 induced-cytokine storm). Reference lists of recognized and notorious articles were reviewed. In addition, all article types regardless of language were measured and case reports were also involved in this review. The key features of appropriate search studies were considered, and the conclusion was summarized in a minireview.

COVID-19 ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME AND ASSOCIATED ACUTE LUNG INJURY

The pathological findings of COVID-19 significantly resemble those of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, Xu et al. illustrate that biopsy taken from the lung of COVID-19 patients is characterized by diffuse bilateral alveolar damage with abundant cellular fibromyxoid exudates, generation of the hyaline membrane, pneumocyte desquamation, and edema, indicating ARDS. In addition, lung interstitial inflammation with lymphocyte predominant and intra-alveolar viral cytopathic changes is observed.[12] However, Gattinoni et al. declare that COVID-19 pneumonia does not cause the typical feature of ARDS.[13]

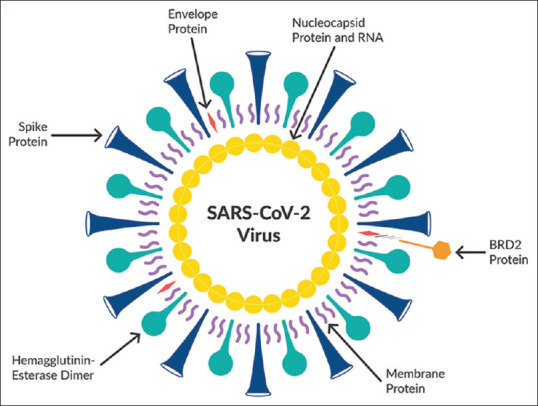

The pathophysiology of ARDS in COVID-19 is due to host hyperimmune response, when SARS-CoV-2 binds pulmonary alveolar cells ACE2; it induces cellular damage and induction of the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from dying pulmonary and immune cells [Figure 3].[14]

Figure 3.

Pathophysiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in acute respiratory distress syndrome[14]

SARS-CoV-2 viral particles provoke host immune activation through activation of the complement cascade and alveolar macrophages which together forming a local immune complex. This immune complex participates in further stimulation of the complement system with augmentation of the systemic immune response through the massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, and interferon-γ.[15]

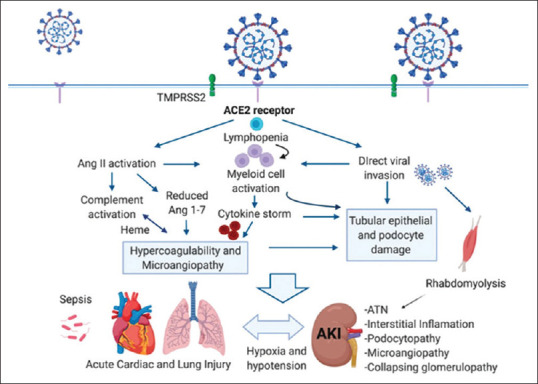

Moreover, infiltrated neutrophils, lymphocytes, and resident macrophages lead to massive alveolar injury, vascular endothelial damage, microvascular thrombosis, and collateral tissue damage due to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators.[14] Indeed, in the end-stage ARDS, the progression of microvascular thrombosis and systemic inflammations lead to multiorgan injury [Figure 4].[16]

Figure 4.

Systemic inflammations and multiorgan injury during severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Wu and Yang reveal that SARS-CoV-2-induced ARDS is associated with cytokine storm mainly in patients with intensive care unit. The severity of symptoms in COVID-19 patients is correlated with the level of inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines.[17] Moreover, IL-22 together with IL-17 and TNF-α provoke the release of endogenous antimicrobial peptide and upregulation of fibrinogen, mucins, serum amyloid protein, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein that contribute in the progression of pulmonary edema. Thus, IL-17 is regarded as a potential biomarker in COVID-19, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and pandemic HINI[18,19] However, Mehta et al. disclose that IL-6 is mainly linked with cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients, so IL-6 antagonist may be of great value in mitigation of cytokine syndrome in COVID-19 pneumonia.[20]

Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase Enzyme Type 5 Inhibitors in COVID-19

PDE5Is such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and the nonselective inhibitor dipyridamole (DIP) are effective anti-inflammatory drugs and may have potential in the management of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[21] Of interest, prophylactic sildenafil therapy improves pulmonary cGMP levels, thereby reducing inflammation, capillary-alveolar protein leakage, alveolar fibrin deposition, and alveolar thickness in experimental ALI. This anti-inflammatory effect is mediated through inhibition of inflammatory cells mainly neutrophils and macrophages.[22] Besides, inhaled NO attenuates ALI through suppression of fibrin deposition and lung inflammation through NO-cGMP-dependent pathway thereby both NO and PDE5Is are interrelated in the mitigation of ALI.[23]

It has been shown that cGMP is involved in the downregulation of pro-inflammatory signaling and leukocyte recruitments in the tracheal smooth muscles. Interestingly, PDE5 was characterized in airway epithelium, airway smooth muscle, and in the media layer of the main pulmonary artery; furthermore, sildenafil induces a potent vasodilatory effect on the pulmonary artery.[24] Therefore, PDE5Is like sildenafil have significant anti-inflammatory effects and attenuation of pulmonary vasoconstrictions in ALI.[25] In ALI, apoptosis of pulmonary alveolar cells leads to dysfunction of endothelial/epithelial barrier through induction of immune reactions. Nevertheless, sildenafil inhibits apoptosis in neonatal rat with ALI through activation of the cGMP/NO pathway.[26]

Recently, Solaimanzadeh found a striking similarity between high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and COVID-19 regarding pulmonary edema, hypoxia, hypocapnia, radiological pulmonary findings, PAH, high fibrinogen, and coagulopathy. Therefore, sildenafil may be of value in the reduction of COVID-19-induced PAH.[27] However, Luks et al. found that COVID-19-induced ARDS is a different entity from that of HAPE as COVID-19-induced ALI has proven to be a heterogeneous disorder and treated by antiviral agents and oxygen therapy unlike HAPE which respond to the oxygen therapy alone.[28]

It has been shown that inhalation of NO may be an effective agent in the management of COVID-19 patients as NO improves blood oxygenation in ARDS.[29]

Previously, in the SARS outbreak during 2002–2003, inhaled NO was useful therapy in the management of SARS-induced ARDS through the reduction of PHT and reduction of lung infiltrates.[30] Therefore, PDE5Is and NO donors improve pulmonary functions mainly ciliary movements and mucus production which together remove viral particles with noteworthy antiviral effect. Since pulmonary NO is downregulated during acute viral infections.[31] Herein, low pulmonary NO may facilitate the entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the development of COVID-19 pneumonia seeing as pulmonary disorders with low NO like cystic fibrosis is highly susceptible for recurrent viral pneumonia.[32]

On the other hand, Mergia and Stegbauer confirmed that PDE5Is reduce the activity of renin–angiotensin system (RAS) through inhibiting the secretion of renal renin.[33] RAS is involved in both acute kidney injuries (AKIs) and ALI in COVID-19-induced ARDS; therefore, AngII serum level is significantly augmented in COVID-19 patients. High AngII leads to AKI, ALI, and cardiovascular complications through impairment of NO production. Therefore, PDE5Is afforded a preventive task against AKI and ALI in the common complications of COVID-19 through the amelioration of AngII-induced endothelial dysfunctions.[34,35]

The binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 provokes innate immunity and coagulopathy leading to cytokine storm and hyperinflammation that collectively cause vasoconstrictions and microvascular injury with reduction of endothelial NO that is regarded as the link between AKI and ALI in COVID-19.[34] Besides, sildenafil reduces the expression and release of IL-6 and IL-8 in different inflammatory diseases; therefore, sildenafil may modulate cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients with ARDS.[36]

Dipyridamole (DIP), a nonspecific PDE5I, (inhibiting PDE2, PDE4, and PDE5)[8] with antiplatelet action has a role in the management of COVID-19, as it has anti-inflammatory and antiviral action as well as mitigation of ALI. Besides, in silico study shows that DIP has significant anti-SARS-CoV-2 with marked improvement of COVID-19 outcomes.[37] DIP, in relationship with its PDE5I effect on platelets as well as its PDE4I effect on lymphocytes, prevents COVID-19-induced coagulopathy through modulation of platelet and lymphocyte counts as well as D-dimer production. Herein, DIP attenuates hypercoagulopathy-induced microvascular complications.[38]

It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 is associated with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), since viral replication is linked with platelet activations and formation of platelet-neutrophil aggregates with the generation of microthrombi. These hemostatic disorders provoke fibrinolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and DAH. Therefore, the administration of antiplatelets like aspirin or DIP in the early phase of COVID-19 may reduce the severity of ARDS through the suppression of platelet-derived pro-inflammatory mediators.[39,40] Indeed, sildenafil possesses significant antiplatelet activity through platelet PDE5 and cGMP-dependent protein kinase.[41]

This study concluded that PDE5Is mainly sildenafil and the nonspecific PDE5I, DIP, have a noteworthy step in the management of COVID-19 patients with ARDS through mitigations of inflammatory changes and associated coagulopathy. Therefore, PDE5Is should be included and recommended in the basic therapeutic regimen of COVID-19 patients to prevent pulmonary and cardiovascular complications.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. Is ivermectin–Azithromycin combination the next step for COVID-19.? Biomedical and Biotechnology Research Journal (BBRJ) 2020;45:101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. Macrolides and COVID-19: An optimum premise. Biomedical and Biotechnology Research Journal (BBRJ) 2020;43:189. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saif LJ, Wang Q, Vlasova AN, Jung K, Xiao S. Coronaviruses. Dis Swine. 2019;66:488–523. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceccarelli M, Berretta M, Rullo EV, Nunnari G, Cacopardo B. Editorial-differences and similarities between severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-coronavirus (CoV) and SARS-CoV-2.Would a rose by another name smell as sweet. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:2781–3. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji HL, Zhao R, Matalon S, Matthay MA. Elevated plasmin (ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility. Physiol Rev. 2020;100:1065–75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horn E, Chakinala MM, Oudiz R, Joseloff E, Rosenzweig EB. EXPRESS: Could pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients be at a lower risk from severe COVID-19? Pulm Circ. 2020;13:2045894020922799. doi: 10.1177/2045894020922799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. Renin–Angiotensin system and fibrinolytic pathway in COVID-19: One-way skepticism. Biomedical and Biotechnology Research Journal (BBRJ) 2020;45:33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tetsi L, Charles AL, Georg I, Goupilleau F, Lejay A, Talha S, et al. Effects of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) on mitochondrial skeletal muscle functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:1883–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yougbare I, Morin C, Senouvo FY, Sirois C, Albadine R, Lugnier C, et al. NCS 613, a potent and specific PDE4 inhibitor, displays anti-inflammatory effects on human lung tissues. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L441–50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00407.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosutova P, Mikolka P, Balentova S, Kolomaznik M, Adamkov M, Mokry J, et al. Effects of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor sildenafil on the respiratory parameters, inflammation and apoptosis in a saline lavage-induced model of acute lung injury. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69:12–9. doi: 10.26402/jpp.2018.5.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dal Moro F, Livi U. Any possible role of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in the treatment of severe COVID19 infections.A lesson from urology? Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108414. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D. Covid-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2020;13:212–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. The Potential Role of Renin Angiotensin System (RAS) and Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) in COVID-19: Navigating the Uncharted.Selected chapters from the reninangiotensin system, Kibel A (Ed) IntechOpen, London. 2020:151–165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. COVID-19 pneumonia in an Iraqi pregnant woman with preterm delivery. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction. 2020;93:156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan CW, Low JG, Wong WH, Chua YY, Goh SL, Ng HJ. Critically Ill COVID-19 infected patients exhibit increased clot waveform analysis parameters consistent with hypercoagulability. Am J Hematol. 2020;22:41–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: An emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zenewicz LA. IL-22: There is a gap in our knowledge. Immunohorizons. 2018;2:198–207. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1800006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Corry DB. The potential role of Th17 immune responses in coronavirus immunopathology and vaccine-induced immune enhancement. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:165–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ntontsi P, Detta A, Bakakos P, Loukides S, Hillas G. Experimental and investigational phosphodiesterase inhibitors in development for asthma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:261–6. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1571582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toward TJ, Smith N, Broadley KJ. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, sildenafil (Viagra), in animal models of airways disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:227–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1372OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jankov RP, Daniel KL, Iny S, Kantores C, Ivanovska J, Ben Fadel N, et al. Sodium nitrite augments lung S-nitrosylation and reverses chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in juvenile rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315:L742–L751. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00184.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauvert O, Lugnier C, Keravis T, Marthan R, Rousseau E, Savineau JP. Effect of sildenafil on cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity, vascular tone and calcium signaling in rat pulmonary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:513–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiss T, Kovacs K, Komocsi A, Tornyos A, Zalan P, Sumegi B, et al. Novel mechanisms of sildenafil in pulmonary hypertension involving cytokines/chemokines, MAP kinases and Akt. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song J, Wang YY, Song P, Li LP, Fan YF, Wang YL. Sildenafil ameliorated meconium-induced acute lung injury in a neonatal rat model. Int J ClinExp Med. 2016;9:10238–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solaimanzadeh I. Acetazolamide, nifedipine and phosphodiesterase inhibitors: Rationale for their utilization as adjunctive countermeasures in the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cureus. 2020;12:e7343. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luks AM, Freer L, Grissom CK, McIntosh SE, Schoene RB, Swenson ER, et al. COVID-19 lung injury is not high altitude pulmonary edema. High Alt Med Biol. 2020;21:192–3. doi: 10.1089/ham.2020.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martel J, Ko YF, Young JD, Ojcius DM. Could nitric oxide help to prevent or treat COVID-19? Microbes Infect. 2020;22:168–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akerström S, Gunalan V, Keng CT, Tan YJ, Mirazimi A. Dual effect of nitric oxide on SARS-CoV replication: Viral RNA production and palmitoylation of the S protein are affected. Virology. 2009;395:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santiago-Olivares C, Rivera-Toledo E, Gómez B. Nitric oxide production is downregulated during respiratory syncytial virus persistence by constitutive expression of arginase 1. Arch Virol. 2019;164:2231–41. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi J, Murata I. Nitric oxide inhalation as an interventional rescue therapy for COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:61. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00681-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mergia E, Stegbauer J. Role of phosphodiesterase 5 and cyclic GMP in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2016;18:39. doi: 10.1007/s11906-016-0646-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AL-KURAISHY HM, Al-Gareeb AI. From SARS-CoV to nCoV-2019: Ruction and argument. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020;152:e102624. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thieme M, Sivritas SH, Mergia E, Potthoff SA, Yang G, Hering L, et al. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-dependent hypertension and renal vascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F474–F481. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Luigi L, Sgrò P, Duranti G, Sabatini S, Caporossi D, Del Galdo F, et al. Sildenafil reduces expression and release of IL-6 and IL-8 induced by reactive oxygen species in systemic sclerosis fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:22–9. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Li Z, Liu S, Chen Z, Zhao Z, Huang YY, et al. Therapeutic effects of dipyridamole on COVID-19 patients with coagulation dysfunction. MedRxiv. 2020;13:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannegieter SC, Klok FA. COVID-19 associated coagulopathy and thromboembolic disease: Commentary on an interim expert guidance. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;11:31–9. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo W, Yu H, Gou J, Li X, Sun Y, Li J, et al. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) Preprints. 2020;2020:2020020407. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou X, Li Y, Yang Q. Antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients complicated by COVID-19: Implications from clinical features to pathological findings. Circulation. 2020;45:63–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang HM, Jin S, Jang H, Kim JY, Lee JE, Kim J, et al. Sildenafil reduces neointimal hyperplasia after angioplasty and inhibits platelet aggregation via activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7769. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]