Abstract

Depression is one of the most prevalent, disabling, and costly mental illnesses currently affecting over 300 million people worldwide. A subset of depressed patients display inflammation as indicated by increased levels of proinflammatory mediators in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Longitudinal and experimental studies suggest that this inflammatory profile may causally contribute to the initiation, maintenance, or recurrence of depressive episodes in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD). While the mechanistic pathways that mediate these depressogenic effects have not yet been fully elucidated, toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling is one potential common inflammatory pathway. In this review, we focus on the role that inflammation plays in depression, TLR signaling and its plasticity as a candidate pathway, its regulation by micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs), and their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for identification of inflammatory subtypes of depression. Pre-clinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that TLR expression and TLR signaling regulators are associated with MDD. Further, TLR expression and signaling is in-turn, regulated in part by miRNAs and some TLR-responsive miRNAs indirectly modulate pathways that are implicated in MDD pathophysiology. These data suggest an intersection between TLR signaling regulation and MDD-linked pathways. While these studies suggest that miRNAs play a role in the pathophysiology of MDD via their regulatory effects on TLR pathways, the utility of miRNAs as biomarkers and potential treatment targets remains to be determined. Developing new and innovative techniques or adapting established immunological approaches to mental health, should be at the forefront in moving the field forward, especially in terms of categorization of inflammatory subtypes in MDD.

Keywords: Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Inflammation, Toll-like Receptors (TLRs), TLR4, miRNA, Exosome

1. Introduction

1.1. Major depressive disorder and role of inflammation

1.1.1. Major depressive disorder (MDD)

Depression is one of the most prevalent, disabling, and costly mental illnesses currently affecting over 300 million people worldwide (WHO, 2020). MDD can be difficult to treat (Berton and Nestler, 2006; Daly et al., 2019) and has major effects on emotional and physical health, negatively impacting daily activities and social interactions. In 2018, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that 7.2% of adults and 14.4% of adolescents (age 12–17) in the United States have experienced at least one major depressive episode, with 4.7% of adults and 10% of adolescents experiencing an MDD episode with severe impairment (McCance-Katz, 2018). As pointed out by Kendler and colleagues the etiology of major depressive disorder (MDD) is complex and involves developmental pathways that may differ between men and women (Kendler et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2006). Disease heterogeneity reflects the complex interaction between multiple biological and social factors. These biological factors include genetics (Shadrina et al., 2018), dysfunction of neurotransmitter or metabolic systems (aan het Rot et al., 2009; Marazziti et al., 2014), hormonal changes (Kitamura et al., 1989), and inflammatory mediators, including proinflammatory cytokines (Haapakoski et al., 2015). There are also social factors that contribute to MDD including early life stress (Carr et al., 2013) and psychosocial stressors (Gilman et al., 2013). Inflammation is a promising disease model that is able to integrate several biological and experiential factors.

1.2. Inflammation and major depressive disorder (MDD)

It is hypothesized that inflammation plays a role in a subset of MDD cases. The source of the inflammation is likely multi-faceted, originating from multiple sources (i.e. periphery and/or central nervous system), and the specific mechanistic pathways that mediate its putative depressogenic effects remain unclear. Elevated concentrations of inflammatory mediators are associated with MDD and the nature of this relationship is bi-directional (Dantzer, 2012). Inflammation impacts the onset, severity, and symptoms of MDD through the modulation of neurogenesis, dopaminergic, and serotonergic metabolism, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation, while MDD, in turn influences cellular immune function via the sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis, thus altering levels of central and peripheral inflammatory mediators (Dantzer, 2018; Felger and Miller, 2012). A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-1β, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) are positively associated with MDD (Dowlati et al., 2010; Enache et al., 2019; Goldsmith et al., 2016; Haapakoski et al., 2015). Thus, pathways that are linked to the production of these inflammatory mediators may be viable candidates for the inflammation observed in MDD patients.

It is well documented that cytokines lead to sickness behavior, the symptoms of which, overlap with those observed in depression, i.e. anhedonia, social isolation, and sleep and appetite changes among others (Dantzer, 2001a). These cytokine-mediated metabolic, neurobiological, and behavioral changes occur through three different pathways: neural, humoral, and cellular (Dantzer et al., 2000). In the neural pathway, visceral afferents traveling in autonomic nerves, particularly the vagus nerve, express cytokine binding sites. Antigen-presenting cells at the sites of inflammation rapidly signal the visceral afferents via both cytokine, and cytokine-independent pathways (Ek et al., 1998; Romanovsky et al., 1997; Savitz and Harrison, 2018). Gene expression changes occur in the solitary nucleus (the primary projection nucleus of the vagus nerve) and higher projection regions within an hour of LPS challenge in rats (Wan et al., 1994). Similarly, in healthy humans LPS induces activation of an analogous neurally-mediated interoceptive pathway (including the insula) 2–3 hours post-infusion (Hannestad et al., 2012). The neural pathway is thought to be most relevant to sickness behavior since it can be prevented by severing the vagus nerve (Luheshi et al., 2000). However, other pathways are also relevant. The humoral pathway involves circulating pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and cytokines that activate cerebral endothelial cells and cells located in the meninges, choroid plexus, and circumventricular organs (Nadeau and Rivest, 1999). Evidence suggests that circulating cytokines are able to 1) enter the brain through active transport at the blood brain barrier (BBB) or volume diffusion at circumventricular organs and 2) be produced at the BBB in response to PAMPs (Quan and Banks, 2007).

The cellular pathway entails monocyte migration into the brain via chemoattractant signals released from activated microglia during times of psychological stress (D’Mello et al., 2009; Drevets et al., 2010; Savitz and Harrison, 2018; Wohleb and Delpech, 2017). Once monocytes infiltrate into the brain, they differentiate into brain macrophages that promote inflammatory signaling in the absence of injury or pathology (Wohleb et al., 2014; Wohleb et al., 2013). These peripherally-derived brain macrophages differ in phenotype from resident microglia and their location along blood vessels makes them well suited for receiving peripheral signals to the brain for antigen presentation and proinflammatory signaling (Guillemin and Brew, 2004; Serrats et al., 2010; Wohleb and Delpech, 2017). Notably, Mechawar and colleagues found that postmortem samples from depressed suicides displayed significantly more blood vessels surrounded by a high density of cells staining positive for a macrophage-specific marker than matched controls, potentially reflecting increased recruitment of circulating monocytes in depressed suicides (Torres-Platas et al., 2014).

2. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling: a candidate pathway

2.1. PAMPs, DAMPs, and everything in between

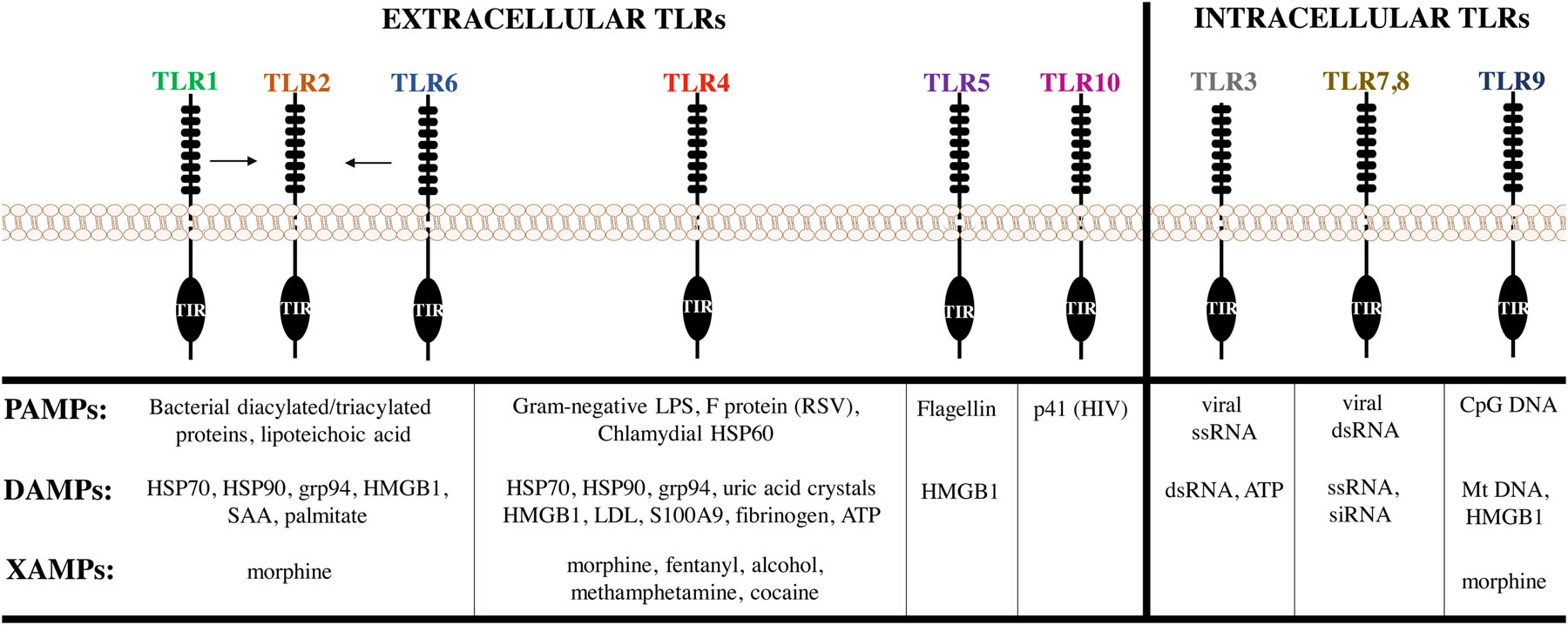

TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that initiate innate immune responses via recognition of select motifs (Figure 1). To date, ten different TLRs have been described in humans and 13 have been characterized in rodents (Takeuchi et al., 2001). These receptors allow for appropriate immune responses to be directed against different classes of pathogens, i.e. bacteria, viruses, and fungi, via receptor localization at either the plasma membrane or in endosomes. TLRs recognize a variety of ligands that include PAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and xenobiotics (XAMPs), which may be altered (i.e. post-translational modifications) during stress-related events leading to increased susceptibility to depression (Slavich and Irwin, 2014).

Figure 1. Toll-like Receptor PAMPs, DAMPs, and XAMPs.

Extracellular (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10) and intracellular (3, 7–9) toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize a variety of pathogenic, self, and substances of abuse known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and xenobiotics (XAMPs), respectively. Abbreviations: TIR-Toll-IL1-receptor domain, HSP-heat shock protein, grp94-glucose-regulated protein 94, HMGB1-high mobility group box-1, SAA-serum amyloid A, LPS-lipopolysaccharide, RSV-respiratory syncytial virus, LDL-low density lipoproteins, ATP-adenosine triphosphate, HIV-human immunodeficiency virus, ss-single stranded, ds-double stranded, CpG-cystine-phosphate-guanine, Mt-mitochondrial.

2.1.1. PAMPs

PAMP recognition occurs via ligand binding to the extracellular N-terminal domain of the receptor. The TLRs located at the plasma membrane, TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10, recognize ligand-specific PAMPs including bacterial tri-acylated proteins (TLR1/6) (Jin et al., 2007), bacterial di-acylated lipoproteins (TLR2/6) (Kang et al., 2009) bacterial flagellin (TLR5) (Hayashi et al., 2001), bacterial lipoteichoic acid (TLR2), and Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (TLR4); some with the aid of their accessory proteins and co-receptor1 (Poltorak et al., 1998). The endosomal-associated TLRs, TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 recognize viral double-stranded (ds) RNA (Alexopoulou et al., 2001), viral single-stranded RNA (Heil et al., 2004), and bacterial or viral unmethylated cystine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) DNA, respectively (Bauer et al., 2001). TLR10 is an orphan receptor but has recently been proposed to recognize dsRNA, the p41 HIV-1 protein (Henrick et al., 2019) or engage anti-inflammatory pathways (Lee et al., 2018).

2.1.2. DAMPs

TLRs also recognize DAMPs that are released from cells during infection, injury, stress, or necrosis categorized as sterile inflammation (Matzinger, 1994). TLR2 and TLR4 recognize the cytosolic heat shock proteins (HSPs) 60, 70, and grp96 (Vabulas et al., 2002); TLR2, 4, 5, and 9 recognize the nuclear protein, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (Scaffidi et al., 2002); and TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 recognize self-nucleic acids (DNA, RNA) (Yu et al., 2010). TLR2 also recognizes palmitate and serum amyloid A (SAA) (He et al., 2009). TLR4 also recognizes SAA (Sandri et al., 2008), extracellular matrix components (fibrinogen, heparan sulfate, fibronectin, hyaluronan), as well as ATP and uric acid crystals (Johnson et al., 2002; Okamura et al., 2001; Taylor et al., 2007). DAMP-mediated activation of TLRs produces sterile inflammatory responses through the TLR signaling pathways, which are discussed below (Yu et al., 2010).

2.1.3. XAMPs

Emerging evidence suggests that TLRs in the central nervous system (CNS) recognize exogeneous small molecules or xenobiotic molecular patterns, knowns as XAMPs (Jacobsen et al., 2014). TLR4, along with its co-receptor, MD2, have been reported to respond to opioids (morphine, fentanyl, methadone) and substances of abuse (methamphetamine, cocaine, alcohol) resulting in changes in glial physiology and morphology, and the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, and CCL2 (Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019). TLRs 2, 8, and 9 have also been implicated in the recognition of XAMPs (Coller and Hutchinson, 2012). Therefore, XAMPs may play a role in ongoing, inflammatory processes that contribute to long-term changes in the brain’s responsiveness to its environment.

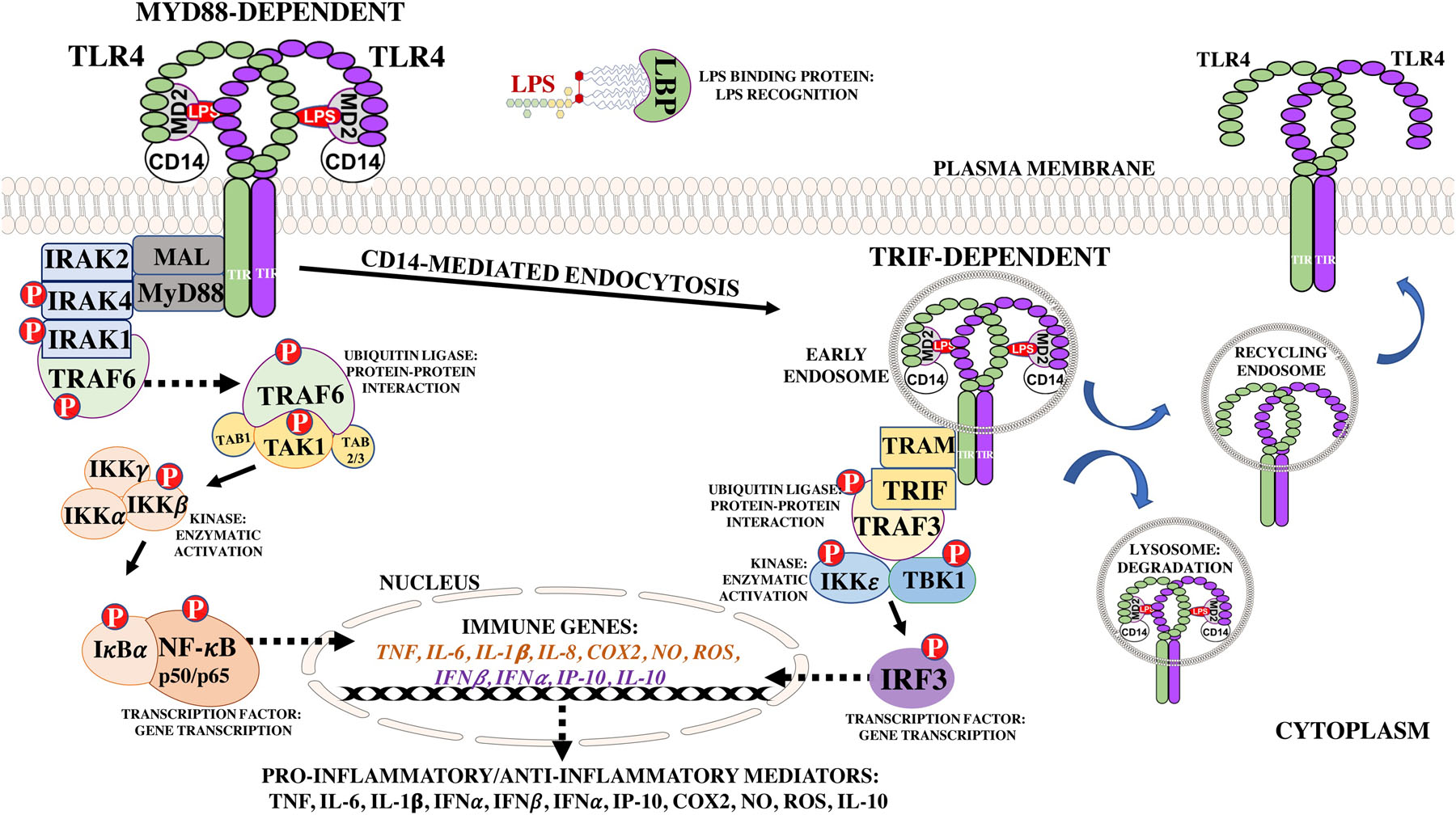

2.2. MyD88 and TRIF-dependent signaling

TLR downstream signaling depends on the recruitment and activation of molecular machinery that confers plasticity to the system. This machinery is necessary for initiation of two-distinct signaling cascades: the myeloid differentiation protein 88 (MyD88)- or the TIR-domain containing adapter inducing IFNβ (TRIF)-dependent signaling pathways. These two pathways are distinguished by the adapter molecules recruited to each receptor (Figure 2). All TLRs, except TLR3, use the MyD88-dependent pathway, in which TIR domains of the TLR interact with TIR domains of the MyD88 adapter leading to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 or the Type I IFNs, IFNα and IFNβ (Akira and Takeda, 2004; Kawai and Akira, 2006). Additionally, TLR2 and TLR4 signaling require the TIR domain-containing adapter protein (TIRAP)/MyD88 adapter-like (MAL) protein bridge for signaling as demonstrated by two studies showing that TIRAP/MAL-deficient mice had defects in inflammatory responses (Fitzgerald et al., 2001). Alternatively, the adapter molecules for the TRIF-dependent pathway, the TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) and TRIF, are recruited to endosomes where TLR3 and TLR4 initiate signaling for the production of Type I interferons (IFN), IFNα and IFNβ (Horng et al., 2002). Curiously, TLR4 is the only receptor that has the ability to use both pathways, thereby producing both proinflammatory cytokines and interferons using four TIR-domain containing adapter molecules.

Figure 2. Myd88- and TRIF-Dependent Toll Like-Receptor 4 Inflammatory Signaling.

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling is initiated upon LPS binding to the leucine-rich repeats located in the N-terminal domain. The MyD88 pathway is initiated upon recruitment of the MAL and MyD88 adapters to the C-terminal TIR domains, which leads to activation of downstream signaling proteins for transcription and activation of pro-inflammatory genes, such as TNF and IL-6. TLR4 is then endocytosed for within 30 minutes of LPS stimulation for initiation of the TRIF-dependent signaling through recruitment of the TRAM and TRIF adapters, leading to activation of cytoplasmic proteins and production of type I interferons, RANTES/CCL5, and IP-10. The TLR4/MD2/CD14-LPS receptor complex then undergoes a Rab7b-mediated lysosomal degradation or TLR4-mediated retrograde transport back to the plasma membrane. Abbreviations- Rantes: Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted, IP-10: IFNγ-inducible protein, NO: nitric oxide, ROS: reactive oxygen species, COX2: cyclooxygenase II enzyme.

The MyD88-dependent pathway initiates downstream signaling events starting with recruitment of adapter molecules, MAL and MyD88, and association with the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) (IRAK1/2 and IRAK4) (Bernard and O’Neill, 2013; Fitzgerald et al., 2001). IRAK4, a serine/threonine kinase, activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated 6 (TRAF6) (Walsh et al., 2015). TRAF6 activates transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) in conjunction with its two co-factors, TAK1-associated binding (TAB) proteins, TAB1 and TAB2/3 (Adhikari et al., 2007; Landstrom, 2010; Ninomiya-Tsuji et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2001). TAK1 activates the beta subunit of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which in turn activates IκBα, the negative regulator of NF-κB (Deng et al., 2000; Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009; Silverman et al., 2003). IκBα forms a complex with NF-κB to prevent its nuclear translocation and binding to κB cis-elements for transcription of immune and inflammatory genes (Oeckinghaus and Ghosh, 2009). Once the MyD88-dependent pathway is initiated, the TLR4/MD2-LPS/CD14 receptor complex on the plasma membrane is endocytosed within 30 minutes of LPS stimulation through a CD14-mediated process, as a regulatory mechanism and to initiate the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway (Balachandran, 2016; Espevik et al., 2003; Husebye et al., 2006; Kagan, 2010; Tan et al., 2015; Zanoni et al., 2011). The receptor complex localized in early endosomes recruits the adapter molecules, TRIF and TRAM, ultimately leading to expression of IFN-inducible genes and late phase activation of NF-κB for production of proinflammatory cytokines (Akira and Takeda, 2004; Kawai et al., 1999; Kawai and Akira, 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2003; Yamamoto et al., 2004). Several downstream signaling molecules are activated through phosphorylation including the E3 ubiquitin ligase, TRAF3, the IκB kinase, IKKε, and tank binding kinase 1 (TBK1). Activation of these proteins leads to translocation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) for transcription of IFNα, IFNβ, IFNγ-inducible protein (IP-10/CXCL10), and Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted (RANTES/CCL5) (Doyle et al., 2002; Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2003; Tseng et al., 2010). The TLR4/MD2-LPS/CD14 receptor complex then undergoes a Rab7b-mediated lysosomal degradation or retrograde transport back to the plasma membrane (Wang et al., 2007).

2.3. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the central nervous system (CNS)

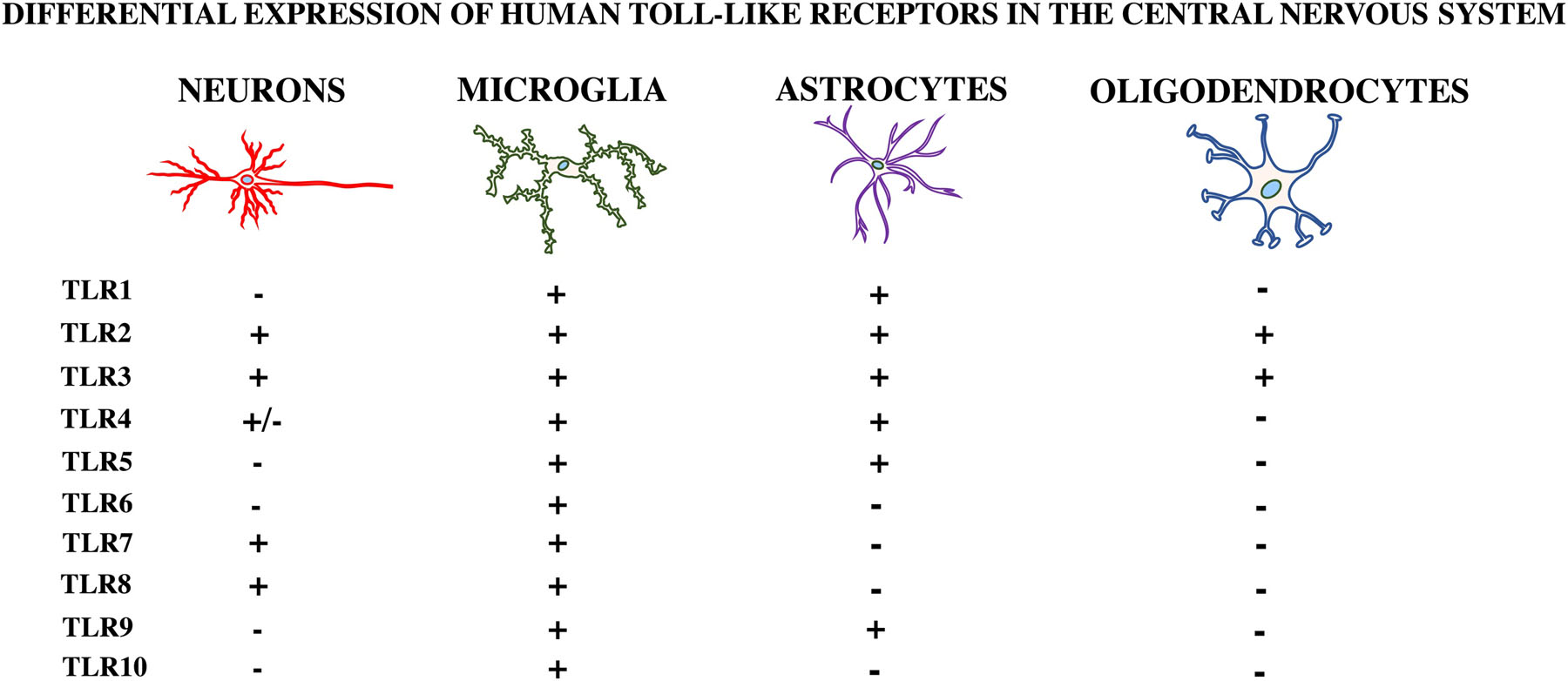

TLRs are not only expressed in peripheral immune cells, but also in the cells of the central nervous system (CNS): microglia, astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes (Kielian, 2009) (Figure 3). Thus, these cells may play a role in altered mood states and could directly affect brain processing leading to depression. Many studies have shown differential expression of TLRs in the CNS, but these data should be interpreted with caution as different studies have used several different species (human, mouse, rat, etc.) and cells types (primary, immortalized, cancer-derived, etc.).

Figure 3. Human Toll-like Receptor Expression in the Central Nervous System.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are differentially expressed in each of the cell types located in the central nervous system (CNS). This figure depicts the putative expression of human TLRs in neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes.

2.3.1. Microglia

Microglia are considered the resident “macrophage” of the brain, with functions such as antigen presentation, debris removal, inflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, synaptic pruning, and ability to recognize PAMPs and DAMPs through their expression of TLRs (Harms et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014b; Schwartz et al., 2013). Primary microglia cultured from human cerebral tissue were shown to express mRNA coding for TLRs 1–10 (Bsibsi et al., 2002). Under basal conditions, mRNA expression of TLR2 and TLR4 was first seen in glial cells located in circumventricular organs, leptomeninges, and the choroid plexus, with lower levels in other regions of CNS (Laflamme and Rivest, 2001). TLR4 is predominantly expressed in microglia and to a lesser extent in other CNS cells (Liu et al., 2014a). Microglia are implicated in the neuroinflammatory and behavioral responses to stress and may contribute to the inflammation-mediated depressive symptoms through release of inflammatory mediators (Wohleb et al., 2014).

2.3.2. Astrocytes

Astrocytes are the most abundant cell type in the CNS, providing trophic and structural support to neurons, which is important to normal physiology (Liu et al., 2014a). Primary astrocytes cultured from human cerebral tissue were shown to express mRNA for TLR2 and TLR3, normal human astrocytes (NHAs) to express TLR3, 4, and 5, while other studies, mainly in rodent and immortalized cell lines, reported expression of TLRs 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8 (Carpentier et al., 2005). TLR4 expression in astrocytes remains controversial as some groups have not been able to replicate these findings (Bsibsi et al., 2006; Lehnardt et al., 2008). Astrocytes may contribute to MDD pathophysiology through serotonin reuptake, but their potential as TLR-expressing cells in MDD is unknown (Liu et al., 2014a; Malynn et al., 2013).

2.3.3. Neurons

Neurons also express TLR4. This was demonstrated using primary mouse neuronal cultures in which RANTES, TNF, IL-6, and CXCL10 were produced via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) transcription factor in response to LPS stimulation (Leow-Dyke et al., 2012). Neurons have also been shown to express TLR2, 3, 7, and 8 (Hung et al., 2018). Interestingly, one report showed high expression of all TLRs, 1–10, in neurons prepared from 16–18-week old human fetal tissue and to a lesser extent in the human neuronal cell lines (Frederiksen et al., 2019). These cells also induced TLR3 and TLR7–8-mediated IFNα and IFNβ mRNA expression in response to polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid [Poly (I:C)] synthetic dsRNA, and ssRNA, respectively (Zhou et al., 2009). Although not classically considered to be immune cells, the importance of neurons expressing TLRs may be overlooked, as they have the ability to generate inflammatory mediators (Leow-Dyke et al., 2012) and possibly contribute to the inflammatory phenotype in MDD.

2.3.4. Oligodendrocytes

Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the CNS (Bradl and Lassmann, 2010). They express TLRs 2, 3, and 4 (Bsibsi et al., 2012). In one study, oligodendrocyte rat cells responded to TLR2 and TLR3-specific ligands, which led to modulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation, survival, myelin-like membrane formation, and, apoptosis, respectively (Bsibsi et al., 2012). Oligodendroglia are highly susceptible to inflammation and reduced numbers or density of these cells have been reported in postmortem MDD samples (Mechawar and Savitz, 2016). Therefore, expression of TLRs in oligodendroglia and their susceptibility to cell death in the presence of inflammation, may lead to their potential role in the pathophysiology of MDD.

Evidence suggests that activation of CNS TLRs by PAMPs, DAMPs, and XAMPs leads to similar signaling mechanisms as seen in the periphery with respect to TLR expression, use of co-receptors, downstream signaling protein activation, and inflammatory and neurotoxic molecule production. Furthermore, TLR recognition, activation, and induction of proinflammatory mediators in the CNS could be an important link between inflammation and MDD. Below we summarize the preclinical, clinical, and postmortem studies that have investigated TLR expression and miRNA profiles in the context of depression.

3. Major depressive disorder (MDD) and Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

3.1. Pre-clinical studies

Pre-clinical studies are useful stepping stones towards understanding the mechanisms through which inflammation may predispose humans to depression (Table 1). A stressed-induced model of depression in rats known as chronic mild stress (CMS), reportedly increased TLR4/MD2 mRNA and protein expression, and inflammatory mediators in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), effects that were reversed after intestinal antibiotic decontamination (Garate et al., 2011). The same group found that CMS exposure increased 1) intestinal permeability, 2) bacterial translocation, 3) TLR-relevant transcription factor activation, and decreased 4) anti-oxidative action (Martin-Hernandez et al., 2016). However, these results and most findings in the studies mentioned below may only be representative of male rats since there are sex differences in depression onset and inflammatory profiles between males and females (Dalla et al., 2010; Klein and Flanagan, 2016; Moieni et al., 2019). Going forward, sex differences may be an important fact to consider in determining the optimal therapeutic interventions. In another study, transcriptome analysis revealed that mice subjected to repeated-social defeat stress (R-SDS), exhibited elevated levels of TLR2 and TLR4-specific DAMPs in the medial PFC, and increased TLR2 and TLR4 mRNA expression in microglia from mice subjected to R-SDS (Nie et al., 2018). R-SDS-induced microglial activation was positively correlated with social avoidance, behavior that was abolished in TLR2/TLR4 double knockout mice (Nie et al., 2018). Consistent with these data, blockade of TLR2 and TLR4, with a TLR2/TLR4 antagonist, OxPAPC, prevented stress-induced potentiation of hippocampal proinflammatory responses after a 24-hour in vivo immune challenge with LPS (Weber et al., 2013). Similarly, administration of OxPAPC prior to the stress challenge prevented sensitized proinflammatory responses from isolated microglia after ex vivo LPS challenge (Weber et al., 2013). These data are consistent with the possibility that TLRs play a key role in mediating stress-induced inflammatory responses that are associated with depression-like behavior.

TABLE 1:

PRE-CLINICAL STUDIES

| Model | Target | Depressive-like behavior protocol | Response | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMS | TLR4 | mFST |

|

Garate I. et al. (2011) |

| CMS | TLR4 |

|

|

Martin- Hernandez D. et al. (2016) |

| R-SDS | TLR2/TLR4 |

|

|

Nie X et al. (2018) |

| Stress Induction | TLR2/TLR4 | Inescapable tail shock |

|

Weber MD et al. (2013) |

Abbreviations- CMS: chronic mild stress; R-SDS: repeated-social defeat stress; TLR2/4: toll-like receptor 2/4; m(FST): modified forced swim test; MD2: myeloid differentiation factor 2; mRNA: message ribonucleic acid; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; IL-1β: interleukin-1beta; COX (2): cyclooxygenase-2; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; 15d-PGJ2: 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1 (tight junction); MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; CD68: cluster of differentiation 68; IL-1α: interleukin-1 alpha; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; IL-6: interleukin-6

3.2. Clinical studies

Several clinical studies have also looked at the association between TLRs and depression by analyzing TLR expression, TLR-related proteins, and cytokine induction in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), monocytes, and postmortem tissue from MDD subjects (Table 2).

TABLE 2:

CLINICAL STUDIES-PBMC, MONOCYTES, POSTMORTEM BRAIN

| MODEL | TARGET | DIAGNOSIS/TREATMENT | RESPONSE | PUBLICATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC | TLRs |

|

|

Hung YY et al. (2014) |

| PBMC | TLRs |

|

|

Hung YY et al. (2016) |

| PBMC | TLRs |

|

|

Hou T-Y et al. (2018) |

| PBMC,monocytes | TLR regulators |

|

|

Hung YY et al. (2017) |

| Monocytes | TNFAIP3 |

|

|

Chen RA et al. (2018) |

| CD14+Monocytes | TLR negative regulators |

|

|

Hung YY (2018) |

| WBC | TLR4 |

|

|

Wu MK et al. (2015) |

| PBMC | TLR4 TLR proteins |

|

|

Keri S. et al. (2014) |

| Postmortem-DLPFC | TLR3/4 |

|

|

Pandey GN et al. (2014) |

| Postmortem-PFC | TLRs |

|

|

Pandey GN et al. (2019) |

| Postmortem-DLPFC | TLR4 TLR proteins |

|

|

Martin-Hernandez D. et al. (2018) |

Abbreviations- PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CD14: cluster of differentiation 14; WBC: whole blood cells; DL(PFC): dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; TLR4: toll-like receptor 4; MDD: major depressive disorder; HC: healthy controls; SSRI: serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: norepinephrine-selective reuptake inhibitor; NDRI; norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor; M: male; F: female; DS: depressed suicide; DNS: depressed non-suicide; NC: normal control; mRNA: message ribonucleic acid; trt: treatment; IL-6: interleukin-6; MyD88s: myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (splice variant); TNFAIP3: TNF alpha induced protein 3; HAMD-17: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; THP-1: human monocytic cell line; TOLLIP: toll-interacting protein; NOD2: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2; NF-κB: nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; CRP: C-reactive protein; HSP70: heat shock protein 70; p38 MAPK: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; JNK: Jun N-terminal kinase; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; DUSP2: Dual specificity protein phosphatase 2

One research group has published several studies with independent samples analyzing TLR and IL-6 mRNA expression in PBMCs, monocytes, and whole blood cells of MDD patients before and after antidepressant treatments (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors, or tetracyclics). TLR mRNA levels were differentially expressed in MDD compared to healthy controls and TLR4 was found to be an independent risk factor relating to severity of MDD (Hung et al., 2014). TLR mRNA levels, which were increased in MDD subjects, decreased after 4 weeks of treatment with SSRIs or SNRIs, putatively indicating a TLR-mediated anti-inflammatory role for antidepressants (Hou, 2018; Hung et al., 2016; Hung et al., 2017). IL-6 mRNA expression in PBMCs from MDD patients and LPS-induced IL-6 mRNA levels in a monocytic cell line were significantly decreased after treatment with a SSRI, but not SNRI, for 4 weeks and 24 hours, respectively (Hung et al., 2017). These data would suggest that SSRIs and SNRIs differentially regulate TLR and cytokine expression and that multiple TLRs may play a role in MDD. However, small sample sizes may also explain these results (Table 2).

The same group also investigated the gene expression profile of several TLR-associated positive and negative regulators in the PBMCs and monocytes of MDD patients before and after antidepressant treatment for 4 weeks. There were no significant differences in TLR-associated positive2 or negative3 regulators, except for the negative regulator, tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3), also known as A20 (Chen et al., 2017; Hung et al., 2017). Baseline TNFAIP3 expression was inversely correlated with depression severity, predicted improvement in depression scores, and increased after antidepressant treatment, suggesting a potential therapeutic target (Chen et al., 2017; Hung, 2018; Hung et al., 2017). Investigation of the association between subscales of the HAMD-17 and peripheral TLR4 mRNA in MDD subjects showed that psychological signs of anxiety and weight loss in HAMD-17 were predictive of TLR4 mRNA levels (Wu et al., 2015).

Keri et al. (2014) analyzed several markers and bacterial translocation (bt) in newly-diagnosed MDD patients (n=50) before and after cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Keri et al., 2014). Relative to healthy controls (n=30), TLR4 mRNA and protein expression, NF-κB mRNA, and 16S ribosomal DNA (bt) were elevated in MDD patients before CBT, but no changes were observed in TLR2 expression, which may indicate ligand specificity (e.g. only Gram-negative LPS was present for changes in TLR4 mRNA, but not TLR2). Reduction of these markers after CBT were associated with more pronounced clinical improvement (Keri et al., 2014). IL-6 and CRP were moderately elevated in MDD and no changes were observed after CBT (Keri et al., 2014). In agreement with other reports, these results suggest that MDD subjects show increased TLR4-related inflammatory mediators and bacterial translocation may contribute to peripheral inflammation in MDD.

In sum, the studies outlined above showed increased TLR and IL-6 mRNA expression, decreased expression of the negative regulator, TNFAIP3/A20, and sporadic associations with depressive symptoms which were reversed by antidepressant treatment. The role of negative regulators, especially TNFAIP3, is largely unknown. But evidence suggests that inhibition of TNFAIP3 leads to NLRP3 inflammasome activation, leading to innate immune activation and susceptibility to depressive-like behavior (Alcocer-Gomez and Cordero, 2014; Cheng et al., 2016). While these findings are suggestive, the evidence should be considered to be preliminary. Sample sizes have been modest, and appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons and demographic/lifestyle factors have not always been performed. Some significant results were also derived from post-hoc analyses. Further, most of these studies were performed by the same group. Thus, independent replications are required.

Two postmortem studies investigated TLR gene and protein expression in the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) of depressed suicide (DS), non-depressed suicide (NDS), and depressed non-suicide (DNS) groups (Table 2) (Pandey et al., 2019; Pandey et al., 2014). Tissue homogenates used for RNA and protein analysis revealed increased levels of TLR3 and TLR4 mRNA expression in the DS and DNS groups and an increase in protein concentrations of TLR3 and TLR4 in DS compared to controls (Pandey et al., 2014). In a follow-up, non-independent study analyzing other TLR family members, TLR2, 3, 4, 6, and 10 protein measured using Western blot was increased in the DS group, but no significant increase was detected in the DNS group compared to controls (Pandey et al., 2019). TLR2 and TLR3 mRNA expression was increased in the DS group and TLR3, 4, and 7 mRNA was increased in the DNS group compared to controls (Pandey et al., 2019). Another postmortem study measured TLR4 protein concentration and TLR pathway mediators in antidepressant-treated and antidepressant-free MDD subjects matched for sex and age with controls (Martin-Hernandez et al., 2018). No significant changes in TLR4 protein expression were detected in the DLPFC but increases in TLR-mediated signaling proteins4 and a reduction in antioxidant and regulatory factors5 were observed with no effect of antidepressant treatment.

Chan et al. (2020) examined methylation differences between MDD and controls in a total of 206 brain samples and 1132 independent blood samples using cell type-specific methylome-wide association studies (MWAS) (Chan et al., 2020). MDD methylation-linked changes in brain and blood were examined focusing on differentiation of cell types including neurons/glia and granulocytes/T and B cells/monocytes using epigenomic deconvolution. The top 1000 findings from each MWAS was tested for gene overlap against GWAS, which showed robust and highly significant overrepresentation of genes implicated by MDD GWASs (Chan et al., 2020). The authors reported significantly enriched pathways for neurons, glia, monocytes, and whole blood. Analysis for glia MWAS showed overlapping pathways related to innate immune responses via TLRs, which strongly implicated TLR activation in MDD and indicates methylation changes that could be indicative of stress-induced brain effects in MDD patients (Chan et al., 2020).

3.2.1. PAMPs and Depression

Mice administered LPS, the prototypical PAMP for TLR4, show decreased motor activity, social withdrawal, reduced appetite, and altered sleep and cognition (Dantzer, 2001b; Konsman et al., 2002; Yirmiya, 1996; Yirmiya, 2000). Yirmiya (1996) and Dantzer (2001a) were the first to draw a link between sickness behavior and the cardinal symptoms of MDD and epidemiological studies by Benros and colleagues have shown that infections are associated with increased risk of developing mental disorders including depression (Benros et al., 2013; Köhler-Forsberg et al., 2019). Potential mechanisms for this risk include direct influence on the CNS, immune activation, inflammatory mediators, genetics, and the microbiome (Benros et al., 2013). Interferon treatment can also cause depressive symptoms such as fatigue, irritability, apathy, anhedonia, insomnia, and memory impairment (Niiranen et al., 1988).

Importantly, these depressive behaviors are not simply an artifact of being sick since they remain present after the acute sickness symptoms have resolved. For instance, mice show increased immobility in the forced swim test and decreased preference for sucrose solutions 24 hours after LPS administration when motor behavior and appetite have returned to normal (Frenois et al., 2007). Moreover, the anhedonic-like behavior is selectively improved by anti-depressants (Yirmiya et al., 1999). Similarly, experimental studies in humans show that low-dose LPS can induce transient depressive symptoms (Irwin et al., 2019). Thus, in theory, the PAMPs associated with systemic infection may produce or exacerbate existing psychiatric symptoms.

3.2.2. DAMPs and Depression

Several DAMPs, including HMGB1, RNA, and HSPs promote depressive-like behaviors in stress models of depression (Franklin et al., 2018). In human studies, increased peripheral concentrations of SAA, uric acid, and S100b have been reported in MDD (Kling et al., 2007; Rothermundt et al., 2001; Tao and Li, 2015; Tsai and Huang, 2016). Taken together, this suggest that DAMPs may contribute to sterile inflammation in MDD patients.

3.3. MyD88 and TRIF gene expression in Depressed Subjects

To our knowledge only one study has examined MYD88 and TRIF expression in depression. Both MyD88 and TRIF mRNA gene expression from PBMCs were reported to be elevated in 38 depressed medical students compared to healthy controls (Hajebrahimi et al., 2014).

3.3.1. TLR-induced cytokines in major depressive disorder

Meta-analyses and clinical studies have reported that depressed subjects and postmortem brains have higher levels of IL-6, TNF, IL-1β compared to healthy controls (HC) (Dahl et al., 2014; Dowlati et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2007; Köhler et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2014; Yoshimura et al., 2009). In theory, the increase in these cytokines could be reflective of cell surface TLR (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10) activation, but one to one mapping is not possible since more than one TLR can drive a particular cytokine response through one specific adaptor, MyD88. While we know that TLR3 and TLR4 are the only TLRs to use TRIF-dependent signaling, this pathway is geared towards type I IFN antiviral responses, which are not implicated in the meta-analyses. The cytokine literature may also be biased as research has tended to focus on cytokines that are easy to measure or are of high-enough concentrations to be reliably measured.

3.3.2. Opioid-Cytokine interaction in major depressive disorder

TLRs and the IL-1 receptor family share homology through their toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domains (O’Neill et al., 2003). IL-1 cytokines modulate mu opioid neurotransmission, which is of particular interest because this opioid neurotransmitter system has been shown to be dysregulated in MDD (Prossin et al., 2016; Prossin et al., 2011). IL-18, whose formation and structure are similar to IL-1β, is a peripheral indicator of immune activation that has been identified to be elevated in MDD (Merendino et al., 2002; Prossin et al., 2011; van de Veerdonk et al., 2011). Prossin AR et al demonstrated that sad mood induction led to increases in IL-18 and decrease during neutral mood induction in MDD subjects vs healthy controls (Prossin et al., 2016). This finding suggests that sad mood induction-mediated changes in IL-18 may be involved in deleterious effects of negative affective states (Prossin et al., 2016). Given that TLRs are homologous to IL-1 receptor family, this cytokine-neurotransmitter system may be one link between peripheral inflammation, central stress response modulation, and affective disorders such as MDD occurring within brain regions that express TLRs.

3.4. miRNAs in TLR signaling

Microribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are small, non-coding, double-stranded RNAs (~19–25 nucleotides) that play a role in mRNA stability and translation (Nejad et al., 2018). The interaction between mature miRNAs and target mRNAs leads to decreased translational efficiency or mRNA degradation, which may play a role in TLR plasticity and depression (Guo et al., 2019). While the innate immune system is important for mounting acute inflammatory responses to clear infections, tight regulation is necessary to prevent chronic inflammation and tissue damage. In this regard, several miRNAs play regulatory roles in innate immunity including the TLR signaling pathway. Therefore, miRNAs may be a modifiable molecular target when it comes to inflammatory responses mediating changes in mental state. For a comprehensive review of known miRNAs involved in the regulatory control of TLRs and downstream signaling proteins including TLR negative regulators, see (Nejad et al., 2018). TLR-responsive miRNAs that are upregulated after stimulation with TLR ligands include miR-9, miR-147, miR-223, and miR-346, while miRNAs that are downregulated after TLR ligand stimulation, include let-7i and miR-125b (Quinn and O’Neill, 2011).

Both in vitro and animal studies suggest that miRNAs either downregulate or upregulate TLR pathway proteins leading to anti- or proinflammatory outcomes. For instance, regulation of let-7 is cell-type dependent, but all three variants, 7i, 7e, and 7b, target the 3’UTR region of TLR4 mRNA leading to an overall decrease in LPS-induced proinflammation (O’Neill et al., 2011; Teng et al., 2013). miR-181c controls microglia-dependent neuronal apoptosis by directly targeting the 3’UTR of TNF mRNA, which also prevents neuronal cell death in BV2 and primary rat microglial cells (Zhang et al., 2012). miR-21 is involved in the negative regulation of NF-κB and the induction of IL-10 via programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4), a key protein responsible for the switch between the LPS-induced proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses (Sheedy et al., 2010). miR-155 regulates TAB2, a NF-κB-regulated protein, thereby suppressing proinflammatory responses (Ceppi et al., 2009). miRNAs can also form a negative feedback loop by targeting genes that upregulate their expression. For example, miR-223 attenuates TLR9/NF-κB signaling by targeting IKKα in a negative feedback loop in neutrophils and miR-147 decreases proinflammatory cytokine expression in mouse macrophages through a negative feedback loop on TLR2, TLR3, and TLR4, in response to their TLR-specific ligands (He et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2009). miR-146a is transcriptionally induced by LPS and is involved in inhibition of bacterial and viral-induced inflammatory responses by targeting TRAF6, IRAK1/2, IL-8, and IFN in a negative feedback loop, thereby preventing prolonged inflammation (Hou et al., 2009; Taganov et al., 2006). Conversely, miR-19a was shown to amplify inflammatory signaling through targeting of negative regulators, SOCS1 and TNFAIP3/A20, thereby increasing production of TH2 cytokines in human airway-infiltrating T cells (Simpson et al., 2014). miR-155 is upregulated in response to LPS in macrophages and mice and enhances the production of TNF by stabilizing TNF transcripts (Thai et al., 2007; Tili et al., 2007). These are just a few examples to the extent in which miRNAs are involved in signaling regulation. For a list of miRNAs, TLR signaling targets, and responses refer to Table 3. Hence, there is potential for miRNAs to serve as diagnostic biomarkers across several diseases, including psychiatric disorders.

TABLE 3:

miRNAs associated with TLR regulation and major depressive disorder

| Toll-like receptor (Nejad C et al 2018) | Major depressive disorder (Lopez JP et al. 2018) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | TARGET | RESPONSE | miRNA | SOURCE | EXPRESSION |

| TLR signaling proteins | TLR-responsive miRNAs | ||||

| Let-7b/e/i, miR-146b, miR-181a | TLR4 | Botha | Let-7b | Whole blood | downregulated |

| miR-21, miR29a | TLR7/8 | Pro-inflammatory | miR-124 | PBMC | downregulated |

| miR-146b, miR-155, miR-203 | MyD88 | Anti-inflammatory | Let-7e, miR-146a, miR-155 | PBMC, monocytes | downregulated |

| miR-146a/b | IRAK1/2 | Anti-inflammatory | MDD-specific miRNAs | ||

| miR-146a | IRAK4 | Anti-inflammatory | Let-7b/c | Whole blood | downregulated |

| miR-124, miR-146a/b | TRAF6 | Anti-inflammatory | miR-132 | Whole blood | upregulated |

| miR-155 | TAB2/3 | Anti-inflammatory | miR-34b-5p, miR-34c-5p | Blood leukocytes | upregulated |

| miR-9, miR-124, miR-155 | p65 NF-κB | Anti-inflammatory | miR-320a | Plasma | downregulated |

| TLR PAMPs | miR-16 | CSF | downregulated | ||

| miR-146 | HMGB-1 | Anti-inflammatory | miR-221-3p, miR-34a-5p, Let-7d-3p | Serum | upregulated |

| TLR Negative Regulators | MDD-specific miRNAs- Postmortem | ||||

| miR-19 | ZBTB16 | Pro-inflammatory | miR-185 | APC | upregulated |

| miR-19, miR-221 | TNFAIP3 | Botha | miR-508-3p, miR-152-3p | APC | downregulated |

| miR-19, miR-155, miR-221/222 | SOCS1 | Pro-inflammatory | miR-1202 | VPC | downregulated |

| Proinflammatory Cytokines | miR-511, miR-340 | Basolateral amygdala | upregulated | ||

| miR-146a, miR-155 | IL-8 | Anti-inflammatory | miR-326 | Midbrain | downregulated |

| Let-7a/b, miR-181a, miR-223 | IL-6 | Botha | miR-34a | ACC | downregulated |

| miR-19a, m R-125b, miR-155 | TNF | Botha | miR-218 | VPC | downregulated |

| miR-146a-5p, miR-146b-5p, miR-24-3p, miR-425-3p | VPC | upregulated | |||

Both: anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory

Abbreviations- TLR: toll-like receptor; MDD: major depressive disorder; MyD88: myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88; IRAK (1,2,4): interleukin receptor-associated kinase; TRAF6: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; TAB (2/3): TGFβ-activated kinase 1 binding protein 2/3; NF-κB: nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; HMGB-1: high mobility group box 1; ZBTB16: Zinc Finger And BTB Domain Containing 16; TNFAIP3: tumor necrosis factor alpha induced protein 3; SOCS1: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1; IL-6: interleukin 6; IL-8: interleukin 8; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; PBMC: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; APC: anterior prefrontal cortex; VPC: ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex

3.5. miRNAs and major depressive disorder

Studies investigating both postmortem and peripheral miRNA changes associated with MDD and treatment effects have been published. The main theme across all studies, is that a set of miRNAs is differentially expressed in MDD individuals relative to comparison subjects, which suggests that these molecules contribute to the inflammatory dysregulation in depression. This dysregulation may include miRNA up or downregulation, and changes in expression levels either above or below threshold values after treatment with antidepressants (Lopez et al., 2018). Additionally, miRNAs similar to those expressed during TLR regulation including let-7e, miR-146a, and miR-155 are also altered in MDD patients and correlate with depression severity (Hung et al., 2019).

It should be noted that several other miRNAs that are not related to TLR regulation have also been implicated in MDD. Accordingly, miR-132 is the most consistently replicated finding. miR-132 is a brain-enriched miRNA and binds to methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a gene known to influence BDNF expression. However, there is as yet no direct evidence for a link between miR-132, BDNF, and MDD (Klein et al., 2007). Other miRNAs modulated in MDD subjects include let-7d, miR-22, miR-103, mir-128, miR-183, miR-192, miR-335, and miR-494, all of which play a role in neuroplasticity, stress responses, and the mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs (Bocchio-Chiavetto et al., 2013). Several other depression-associated miRNAs regulate PI3K-AKT, neurotropin, and MAPK signaling pathways (Ferrua et al., 2019). Thus, TLR-responsive and MDD-dependent miRNAs may serve as possible biomolecular targets for the development of novel treatments.

The above studies suggest that 1) miRNA expression is dysregulated in MDD subjects and therefore could theoretically aid in the diagnosis of inflammatory subtypes of MDD, 2) miRNA profiles could conceivably be used as treatment response biomarkers as changes in miRNA expression are reversed after antidepressant treatment, but also that 3) additional research into the relationship between miRNAs and MDD would be beneficial as there are too few studies to draw firm conclusions. The question also arises as to whether or not we can accurately determine MDD inflammatory subtypes using miRNAs that have been studied in peripheral immune cells and blood. While these studies advance the field with respect to miRNA expression, dysregulation in MDD patients, and changes in response to treatment, one underlying issue that has not been addressed is the use of peripheral miRNA and inflammatory profiles to inform, diagnose, and identify biotypes of MDD.

4. Future Perspectives

This review highlights the potential importance of TLR signaling and its regulation in depression. That is, 1) TLR signaling as a theoretical suspect in inflammation-mediated depression, 2) data from pre-clinical, clinical, and postmortem studies implicating TLRs in depression, and 3) miRNA profiles associated with both TLR signaling and MDD. A limitation of this work is that we did not perform a systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. Further, while we note the potential that different types of TLRs may have on inflammation-mediated depression, the review is primarily focused on the TLR4 pathway and its conceivable effect on depression.

Besides TLR4-induced LPS signaling being a potential pathway involved in inflammation-mediated depression, it is possible for other TLR-specific ligands to also be responsible for triggering this process, as changes in other TLRs have been reported in the DLFPC, PBMCs, and whole blood in MDD (Pandey et al., 2018). For instance, 1) LPS from Gram-negative bacterial strains resulting from leaky gut can activate TLR4 (Maes et al., 2008), 2) DAMPs particularly associated with depression or immunogenic, such as HSP70 and HMGB1, which can activate TLR1/6 or TLR5 (Chavan et al., 2012; Franklin et al., 2018), 3) latent viruses such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), also trigger TLR4 TRIF-dependent signaling (Yew et al., 2012), and lastly, 4) XAMPs, such as opioid agonists, which have been shown to activate TLR4 signaling in a similar fashion to LPS (Hutchinson et al., 2010). Notwithstanding these possibilities, there remains a need to consider alternative ways of determining the molecular mechanisms associated with inflammation-mediated depression and devising new strategies for the effective categorization of inflammatory subtypes. Outlined below are several perspectives on how progress could be made in this regard.

A well-established and cutting-edge technique in other fields, but new in the field of psychiatry, is the potential for using brain-derived exosome isolation to provide insight into molecular processes occurring in the brain. Exosomes are extracellular vesicles 30 to 150 nm in size, and contain cellular cargo such as the DNA, RNA, and protein machinery used for intercellular communication, neuroinflammatory processes, and regulation (Brites and Fernandes, 2015; Mustapic et al., 2017). Theoretically, brain-derived exosomal content can provide a window into the brain, particularly during disease states. Brain exosomes cross the blood brain barrier bi-directionally and can be isolated from multiple sources including cerebrospinal fluid, urine, whole blood, plasma, and serum (Mustapic et al., 2017). Thus, one way forward is to consider careful examination of brain-derived exosomal TLR and miRNA expression to determine pathways dysregulated in MDD and cells contributing to MDD pathology.

Also, genetic variants have been shown to influence inflammatory processes including the TLR4 signaling pathway (Ferreira et al., 2013; Meena et al., 2013). Research uncovered two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the TLR4 gene, AspD299Gly (D299G) and Thr399Ile (T399I), which occur in humans with a frequency of 10–18% (Arbour et al., 2000). D299G and T399I are associated with a LPS hypo-responsive phenotype, which leads to higher incidence of gram-negative bacterial infections, viral infections, and increased risk for sepsis (Agnese et al., 2002; Awomoyi et al., 2007; Figueroa et al., 2012). TLR4 SNPs are associated with several diseases such as atherosclerosis, asthma, and Crohn’s disease, but to our knowledge, there are no studies investigating whether TLR4 SNPs are associated with inflammation-mediated MDD. TLR4 genetic variants could be used to determine whether these variants are associated with inflammation-mediated depression.

In vitro pre-clinical studies focusing on depressive-like behavior and TLR4 signaling have provided useful mechanistic data, but these in vitro experiments have certain limitations, as the results may not always be fully translatable to humans. Several studies have analyzed inflammatory markers in depressed subjects but like all cross-sectional studies lack explanatory depth. Experimental studies using in vivo immune challenges with LPS or the typhoid vaccine have been performed, providing useful insight into the behavioral, immunological, and neurophysiological effects of inflammatory stimuli in healthy subjects (Eisenberger et al., 2010; Harrison et al., 2009; Irwin et al., 2019; Moieni et al., 2015; Moieni et al., 2019). However, unlike the aforementioned studies in which the healthy subjects were given LPS (immune challenge) to activate the immune response, an immune challenge via TLR4 has not yet been performed in individuals with MDD. Such a study could provide: 1) insight into temporal-specific differences in TLR4 signaling between depressed subjects and healthy controls or depressed individuals with and without inflammation, and 2) more precise, translational findings during an active pathophysiological disease state.

This review highlights the importance and implications on resolving immunological mechanisms underlying inflammation-mediated depression, which is critical for developing targeted interventions. Emerging evidence outlining immunological, behavioral, and neurocognitive changes as a result of stimulation with the LPS, the TLR4 ligand, suggest that focusing on TLR4 signaling mechanisms and its involvement in depression is forward-thinking and may uncover new and innovative approaches to the field of mental health.

Highlights.

A subset of major depressive disorder (MDD) patients display inflammation

Studies suggest inflammation may causally contribute to depressive episodes

Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling is a candidate for inflammation-mediated MDD

Micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) may serve as diagnostic biomarkers in MDD

TLR pathways and related miRNAs may serve as novel targets for MDD biotypes

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported in part by The William K. Warren Foundation, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM121312), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH113871). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- IL-1ra

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- TIR

toll-IL-1 receptor domain

- DAMPs

damage-associated molecular patterns

- XAMPs

xenobiotics

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- CpG

cystine-phosphate-guanine

- HSPs

heat shock proteins

- HMGB-1

high mobility group box 1

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation protein 88

- TRIF

TIR-domain containing adapter inducing interferon beta (IFNβ)

- CNS

central nervous system

- Grp94

glucose-related protein 94

- SAA

serum amyloid A

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- LDL

low density lipoproteins

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- Ss

single-stranded

- ds

double-stranded

- Mt

mitochondrial

- TIRAP

TIR domain containing adapter protein

- MAL

MyD88 adapter-like

- TRAM

TRIF-related adapter molecule

- IFN

interferon

- IRAKs

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases

- TRAF6

tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated 6

- TAK1

transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1

- TAB

TAK1-associated binding proteins

- IKK

IκB kinase complex

- IRF3

interferon regulatory factor 3

- IP-10/CXCL10

IFNγ-inducible protein

- RANTES/CCL5

Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted

- NO

nitric oxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- COX

cyclooxygenase II enzyme

- NHAs

normal human astrocytes

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- Poly (I:C)

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CMS

chronic mild stress

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- R-SDS

repeated-social defeat stress

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TOLLIP

Toll-interacting protein

- MyD88s

myeloid differentiation 88 short

- NOD2

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2

- TNFAIP3

TNFα-induced protein

- SOCS1

suppressor of cytokine signaling 1

- DL

dorsolateral

- DLPFC

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor (erythroid factor 2-derived)-like 2

- DUSP2

Dual-specificity phosphate 2

- miRNA

micro ribonucleic acids

- mRNA

messenger RNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accessory proteins for TLR2 and TLR4 are CD36 and CD14, respectively; and the co-receptor for TLR4 is MD2

Pellino 1, tumor necrosis factor-associated receptor 6 (TRAF6), and interleukin-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1)

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2), Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), Toll interacting protein (TOLLIP), Single Immunoglobulin and Toll-Interleukin 1 Receptor (TIR) Domain (SIGIRR), Suppressor of Tumorgenicity (ST2L), and IRAK3

Heat shock protein (HSP70), p38 MAPK, and JNK

Nuclear factor (erythroid factor 2-derived)-like 2 (Nrf2), DUSP2: Dual-specificity phosphate 2 (DUSP2)

REFERENCES

- Aan Het Rot M, Mathew SJ, Charney DS, 2009. Neurobiological mechanisms in major depressive disorder. CMAJ. 180, 305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ, 2007. Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene. 26, 3214–3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnese DM, Calvano JE, Hahm SJ, Coyle SM, Corbett SA, Calvano SE, Lowry SF, 2002. Human toll-like receptor 4 mutations but not CD14 polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of gram-negative infections. J. Infect. Dis 186, 1522–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K, 2004. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcocer-Gomez E, Cordero MD, 2014. NLRP3 inflammasome: a new target in major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther 20, 294–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA, 2001. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 413, 732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, Zabner J, Kline JN, Jones M, Frees K, Watt JL, Schwartz DA, 2000. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat. Genet 25, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awomoyi AA, Rallabhandi P, Pollin TI, Lorenz E, Sztein MB, Boukhvalova MS, Hemming VG, Blanco JC, Vogel SN, 2007. Association of TLR4 polymorphisms with symptomatic respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants and young children. J. Immunol 179, 3171–3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran Y, 2016. Role of endocytosis in TLR signaling: an effective negative regulation to control inflammation. MOJ Immunol. 3, 00111. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Kirschning CJ, Hacker H, Redecke V, Hausmann S, Akira S, Wagner H, Lipford GB, 2001. Human TLR9 confers responsiveness to bacterial DNA via species-specific CpG motif recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 98, 9237–9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benros ME, Waltoft BL, Nordentoft M, Ostergaard SD, Eaton WW, Krogh J, Mortensen PB, 2013. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry. 70, 812–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard NJ, O’neill LA, 2013. Mal, more than a bridge to MyD88. IUBMB Life. 65, 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, Nestler EJ, 2006. New approaches to antidepressant drug discovery: beyond monoamines. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 7, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio-Chiavetto L, Maffioletti E, Bettinsoli P, Giovannini C, Bignotti S, Tardito D, Corrada D, Milanesi L, Gennarelli M, 2013. Blood microRNA changes in depressed patients during antidepressant treatment. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 23, 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradl M, Lassmann H, 2010. Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites D, Fernandes A, 2015. Neuroinflammation and Depression: Microglia Activation, Extracellular Microvesicles and microRNA Dysregulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci 9, 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bsibsi M, Nomden A, Van Noort JM, Baron W, 2012. Toll-like receptors 2 and 3 agonists differentially affect oligodendrocyte survival, differentiation, and myelin membrane formation. J. Neurosci. Res 90, 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bsibsi M, Persoon-Deen C, Verwer RW, Meeuwsen S, Ravid R, Van Noort JM, 2006. Toll-like receptor 3 on adult human astrocytes triggers production of neuroprotective mediators. Glia. 53, 688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bsibsi M, Ravid R, Gveric D, Van Noort JM, 2002. Broad expression of Toll-like receptors in the human central nervous system. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 61, 1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier PA, Begolka WS, Olson JK, Elhofy A, Karpus WJ, Miller SD, 2005. Differential activation of astrocytes by innate and adaptive immune stimuli. Glia. 49, 360–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CP, Martins CMS, Stingel AM, Lemgruber VB, Juruena MF, 2013. The Role of Early Life Stress in Adult Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review According to Childhood Trauma Subtypes. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 201, 1007–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, Barras E, Reith W, Santos MA, Pierre P, 2009. MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 2735–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RF, Turecki G, Shabalin AA, Guintivano J, Zhao M, Xie LY, Van Grootheest G, Kaminsky ZA, Dean B, Penninx B, Aberg KA, Van Den Oord E, 2020. Cell Type-Specific Methylome-wide Association Studies Implicate Neurotrophin and Innate Immune Signaling in Major Depressive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan SS, Huerta PT, Robbiati S, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Ochani M, Dancho M, Frankfurt M, Volpe BT, Tracey KJ, Diamond B, 2012. HMGB1 Mediates Cognitive Impairment in Sepsis Survivors. Mol. Med 18, 930–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RA, Huang TL, Huang KW, Hung YY, 2017. TNFAIP3 mRNA Level Is Associated with Psychological Anxiety in Major Depressive Disorder. Neuroimmunomodulation. 24, 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Pardo M, Armini RS, Martinez A, Mouhsine H, Zagury JF, Jope RS, Beurel E, 2016. Stress-induced neuroinflammation is mediated by GSK3-dependent TLR4 signaling that promotes susceptibility to depression-like behavior. Brain. Behav. Immun 53, 207–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JK, Hutchinson MR, 2012. Implications of central immune signaling caused by drugs of abuse: mechanisms, mediators and new therapeutic approaches for prediction and treatment of drug dependence. Pharmacol. Ther 134, 219–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’mello C, Le T, Swain MG, 2009. Cerebral microglia recruit monocytes into the brain in response to tumor necrosis factoralpha signaling during peripheral organ inflammation. J. Neurosci 29, 2089–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J, Ormstad H, Aass HC, Malt UF, Bendz LT, Sandvik L, Brundin L, Andreassen OA, 2014. The plasma levels of various cytokines are increased during ongoing depression and are reduced to normal levels after recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 45, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla C, Pitychoutis PM, Kokras N, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, 2010. Sex Differences in Animal Models of Depression and Antidepressant Response. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 106, 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, Li H, Zhang Y, Li X, Lane R, Lim P, Duca AR, Hough D, Thase ME, Zajecka J, Winokur A, Divacka I, Fagiolini A, Cubala WJ, Bitter I, Blier P, Shelton RC, Molero P, Manji H, Drevets WC, Singh JB, 2019. Efficacy of Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus Oral Antidepressant Treatment for Relapse Prevention in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2001a. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 933, 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2001b. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: where do we stand? Brain Behav Immun. 15, 7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2012. Depression and inflammation: an intricate relationship. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2018. Neuroimmune Interactions: From the Brain to the Immune System and Vice Versa. Physiol. Rev 98, 477–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Konsman JP, Bluthe RM, Kelley KW, 2000. Neural and humoral pathways of communication from the immune system to the brain: parallel or convergent? Auton. Neurosci 85, 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ, 2000. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell. 103, 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctot KL, 2010. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S, Vaidya S, O’connell R, Dadgostar H, Dempsey P, Wu T, Rao G, Sun R, Haberland M, Modlin R, Cheng G, 2002. IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity. 17, 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets DA, Dillon MJ, Schawang JE, Stoner JA, Leenen PJ, 2010. IFN-gamma triggers CCR2-independent monocyte entry into the brain during systemic infection by virulent Listeria monocytogenes. Brain. Behav. Immun 24, 919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Inagaki TK, Mashal NM, Irwin MR, 2010. Inflammation and social experience: an inflammatory challenge induces feelings of social disconnection in addition to depressed mood. Brain. Behav. Immun 24, 558–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek M, Kurosawa M, Lundeberg T, Ericsson A, 1998. Activation of vagal afferents after intravenous injection of interleukin-1beta: role of endogenous prostaglandins. J. Neurosci 18, 9471–9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache D, Pariante CM, Mondelli V, 2019. Markers of central inflammation in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain tissue. Brain. Behav. Immun 81, 24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espevik T, Latz E, Lien E, Monks B, Golenbock DT, 2003. Cell distributions and functions of Toll-like receptor 4 studied by fluorescent gene constructs. Scand. J. Infect. Dis 35, 660–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan N, Luo Y, Ou Y, He H, 2017. Altered serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-18 in depressive disorder patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 32, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger JC, Miller AH, 2012. Cytokine effects on the basal ganglia and dopamine function: the subcortical source of inflammatory malaise. Front. Neuroendocrinol 33, 315–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RC, Freitag DF, Cutler AJ, Howson JM, Rainbow DB, Smyth DJ, Kaptoge S, Clarke P, Boreham C, Coulson RM, Pekalski ML, Chen WM, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Rich SS, Butterworth AS, Malarstig A, Danesh J, Todd JA, 2013. Functional IL6R 358Ala allele impairs classical IL-6 receptor signaling and influences risk of diverse inflammatory diseases. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrua CP, Giorgi R, Da Rosa LC, Do Amaral CC, Ghisleni GC, Pinheiro RT, Nedel F, 2019. MicroRNAs expressed in depression and their associated pathways: A systematic review and a bioinformatics analysis. J. Chem. Neuroanat 100, 101650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa L, Xiong Y, Song C, Piao W, Vogel SN, Medvedev AE, 2012. The Asp299Gly polymorphism alters TLR4 signaling by interfering with recruitment of MyD88 and TRIF. J. Immunol 188, 4506–4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, Mcwhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T, 2003. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol 4, 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-Mcdermott EM, Bowie AG, Jefferies CA, Mansell AS, Brady G, Brint E, Dunne A, Gray P, Harte MT, Mcmurray D, Smith DE, Sims JE, Bird TA, O’neill LA, 2001. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 413, 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TC, Xu C, Duman RS, 2018. Depression and sterile inflammation: Essential role of danger associated molecular patterns. Brain. Behav. Immun 72, 2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen HR, Haukedal H, Freude K, 2019. Cell Type Specific Expression of Toll-Like Receptors in Human Brains and Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomed Res Int. 2019, 7420189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenois F, Moreau M, O’connor J, Lawson M, Micon C, Lestage J, Kelley KW, Dantzer R, Castanon N, 2007. Lipopolysaccharide induces delayed FosB/DeltaFosB immunostaining within the mouse extended amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus, that parallel the expression of depressive-like behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 32, 516–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garate I, Garcia-Bueno B, Madrigal JL, Bravo L, Berrocoso E, Caso JR, Mico JA, Leza JC, 2011. Origin and consequences of brain Toll-like receptor 4 pathway stimulation in an experimental model of depression. J. Neuroinflammation 8, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Trinh NH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Murphy JM, Breslau J, 2013. Psychosocial stressors and the prognosis of major depression: a test of Axis IV. Psychol. Med 43, 303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ, 2016. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1696–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ, 2004. Microglia, macrophages, perivascular macrophages, and pericytes: a review of function and identification. J. Leukoc. Biol 75, 388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Hong W, Wang X, Zhang P, Korner H, Tu J, Wei W, 2019. MicroRNAs in Microglia: How do MicroRNAs Affect Activation, Inflammation, Polarization of Microglia and Mediate the Interaction Between Microglia and Glioma? Front. Mol. Neurosci 12, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapakoski R, Mathieu J, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimaki M, 2015. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain. Behav. Immun 49, 206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajebrahimi B, Bagheri M, Hassanshahi G, Nazari M, Bidaki R, Khodadadi H, Arababadi MK, Kennedy D, 2014. The adapter proteins of TLRs, TRIF and MYD88, are upregulated in depressed individuals. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract 18, 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannestad J, Subramanyam K, Dellagioia N, Planeta-Wilson B, Weinzimmer D, Pittman B, Carson RE, 2012. Glucose metabolism in the insula and cingulate is affected by systemic inflammation in humans. J Nucl Med. 53, 601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms AS, Cao S, Rowse AL, Thome AD, Li X, Mangieri LR, Cron RQ, Shacka JJ, Raman C, Standaert DG, 2013. MHCII Is Required for α-Synuclein-Induced Activation of Microglia, CD4 T Cell Proliferation, and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration. The Journal of Neuroscience. 33, 9592–9600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison NA, Brydon L, Walker C, Gray MA, Steptoe A, Critchley HD, 2009. Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, Hawn TR, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Eng JK, Akira S, Underhill DM, Aderem A, 2001. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 410, 1099–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He RL, Zhou J, Hanson CZ, Chen J, Cheng N, Ye RD, 2009. Serum amyloid A induces G CSF expression and neutrophilia via Toll-like receptor 2. Blood. 113, 429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liu X, Jiang K, Peng D, Hong W, Fang Y, Qian Y, Yu S, Li H, 2016. Alterations of microRNA-124 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in pre- and post-treatment patients with major depressive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res 78, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, Lipford G, Wagner H, Bauer S, 2004. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 303, 1526–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrick BM, Yao XD, Zahoor MA, Abimiku A, Osawe S, Rosenthal KL, 2019. TLR10 Senses HIV-1 Proteins and Significantly Enhances HIV-1 Infection. Front. Immunol 10, 482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R, 2002. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 420, 329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Wang P, Lin L, Liu X, Ma F, An H, Wang Z, Cao X, 2009. MicroRNA-146a feedback inhibits RIG-I-dependent Type I IFN production in macrophages by targeting TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2. J. Immunol 183, 2150–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T-Y, Huang Tl, Lin Cc, Wu Mk, Hung Yy, 2018. Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhiibitors and Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors on Toll-Like Receptors Expression Profiles. Neuropsychiatry. 8, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hung Y-F, Chen C-Y, Shih Y-C, Liu H-Y, Huang C-M, Hsueh Y-P, 2018. Endosomal TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8 control neuronal morphology through different transcriptional programs. The Journal of Cell Biology. 217, 2727–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YY, 2018. Antidepressants Improve Negative Regulation of Toll-Like Receptor Signaling in Monocytes from Patients with Major Depression. Neuroimmunomodulation. 25, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YY, Huang KW, Kang HY, Huang GY, Huang TL, 2016. Antidepressants normalize elevated Toll-like receptor profile in major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 233, 1707–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YY, Kang HY, Huang KW, Huang TL, 2014. Association between toll-like receptors expression and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 220, 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YY, Lin CC, Kang HY, Huang TL, 2017. TNFAIP3, a negative regulator of the TLR signaling pathway, is a potential predictive biomarker of response to antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder. Brain. Behav. Immun 59, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YY, Wu MK, Tsai MC, Huang YL, Kang HY, 2019. Aberrant Expression of Intracellular let-7e, miR-146a, and miR-155 Correlates with Severity of Depression in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder and Is Ameliorated after Antidepressant Treatment. Cells. 8, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebye H, Halaas O, Stenmark H, Tunheim G, Sandanger O, Bogen B, Brech A, Latz E, Espevik T, 2006. Endocytic pathways regulate Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and link innate and adaptive immunity. EMBO J. 25, 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]