Abstract

Objective

To determine differences in incidence and duration of postoperative symptomatic hypocalcemia between those taking and those not taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at the time of total or completion thyroidectomy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of adult patients who underwent total or completion thyroidectomy at a tertiary medical center between January 2013 and January 2018 was performed. Development of symptomatic hypocalcemia, duration of symptoms, postoperative parathyroid hormone levels, PPI usage and emergency department (ED) visits were recorded.

Results

Data from 371 patients were analyzed. Sixty of 371 (16.2%) patients developed symptomatic hypocalcemia. Sixteen of 89 (18.0%) patients on a PPI developed symptomatic hypocalcemia compared to 44 of 282 (15.6%) not on a PPI (P = .63). The overall average duration of symptoms was 4.3 days (SD [SD] 3.77 days). The average duration of symptoms in those on a PPI was 4.8 days (SD 2.8 days) compared to 4.2 days (SD 4.1 days) in those not on a PPI (P = 0.16). Six of 282 patients (2.1%) not taking a PPI had a postoperative ED visit, compared to two of the 89 patients (2.3%) taking a PPI (P = 1.00).

Conclusions

There was no clinically significant difference in incidence and duration of symptomatic hypocalcemia or ED visits after total or completion thyroidectomy between patients that were and were not taking PPIs perioperatively. While the decision to continue PPI should be made on an individual basis, these data suggest that patients may be counseled to continue their PPI perioperatively without increased risk of symptomatic hypocalcemia.

Level of Evidence

3.

Keywords: hypocalcemia, proton pump inhibitors, thyroidectomy

A retrospective review to determine differences in incidence and duration of symptomatic hypocalcemia between adults taking and not taking proton pump inhibitors after total or completion thyroidectomy was performed. Three‐hundred and seventy‐one patients were included, and there were no statistically significant differences in incidence or duration of symptoms between the two groups. While the decision to continue PPI should be made on an individual basis, these data suggest that patients may be counseled to continue their PPI perioperatively without increased risk of symptomatic hypocalcemia.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since being introduced in the 1980s, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have become one of the most widely used medications in the world. 1 Over 7% of adults in the United States take prescription PPIs, while an even greater number acquire them over the counter. 2 The dramatic rise in their usage is attributed to their potent inhibition of gastric acid secretion, making them the treatment of choice for acid‐related gastrointestinal disorders. 3 Although generally considered to be effective and well tolerated, long‐term use of PPIs has been linked to adverse consequences, including decreased calcium absorption. 4 The mechanism behind PPI‐induced hypocalcemia is thought to be related to decreased calcium bioavailability in the setting of gastric achlorhydria, as calcium absorption is a pH‐dependent process. 5 , 6 , 7 Additionally, PPIs can induce hypomagnesemia, which can be another contributor to hypocalcemia by impairing PTH release. 8

A possible complication of thyroidectomy is transient or permanent hypocalcemia due to iatrogenic damage to or removal of the parathyroid glands. 9 Due to the effect of PPIs on calcium absorption, patients undergoing thyroidectomy while on these medications may be at increased risk for symptomatic hypocalcemia. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether there is an increased incidence and duration of symptomatic hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy in patients taking PPIs compared to those that are not.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

An Institutional Review Board‐approved retrospective chart review was performed for patients that underwent total or completion thyroidectomy between January 1, 2013 and January 1, 2018 at the University of Vermont Medical Center. Patients were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code and included if they underwent total thyroidectomy (CPT 60240), completion thyroidectomy (CPT 60260), total thyroidectomy with limited (CPT 60252) or radical (CPT 60254) neck dissection, or total substernal thyroidectomy (CPT 60271). Medical records were reviewed by the first three authors (DG, NG, VT). Demographic data such as age, sex and race were collected. Clinical characteristics, including smoking status, medical comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, end stage renal disease, hypertension, GERD, and history of gastric bypass), proton pump inhibitor use at the time of surgery, postoperative PTH and calcium levels, postoperative calcium and vitamin D supplementation regimen, duration of postoperative hypocalcemia symptoms and postoperative emergency department (ED) visits were collected. Per protocol, all patients with a postoperative PTH less than 12 pg/mL were instructed to start scheduled calcium carbonate 1000 mg four times daily and calcitriol 0.25 mcg twice daily until seen in follow‐up. Symptoms of hypocalcemia included perioral or extremity paresthesias, muscle cramping, and muscle spasm. Patients were excluded from analysis if they had a history of gastric bypass surgery, end stage renal disease or preoperative hyperparathyroidism, underwent concurrent total laryngectomy, had unclear duration of symptomatic hypocalcemia or had permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. The latter was defined by the need for supplemental calcium and vitamin D beyond 6 months from surgery. The statistical results for categorical data were based on either the chi‐square test or, when cell counts were less than 10, Fisher's exact test. Duration of symptoms was evaluated with the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Multivariate analysis to control for confounding factors was performed using logistic regression. Analyses were run using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

3. RESULTS

Four hundred and eight patients were initially identified. Thirty‐seven were excluded: 10 had postoperative permanent hypoparathyroidism, seven had preoperative hyperparathyroidism, three were lost to follow‐up, nine had duration of symptoms that were unable to be determined by chart review, three underwent concurrent total laryngectomy, and five had a history of gastric bypass surgery. The remaining 371 patients were included in the statistical analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in sex and smoking status between those that were on a PPI at the time of surgery compared to those who were not. However, patients on PPIs were more likely to have older age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic data

| Characteristic | Total (n = 371) | Not on PPI a (n = 282) | On PPI (n = 89) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD b ) | ||||

| Age | 50.4 (15.4) | 49.0 (16.1) | 54.9 (12.2) | P = .0016 |

| n (%) | ||||

| Male | 87 (23.5) | 60 (21.3) | 27 (30.3) | P = .086 |

| Female | 284 (76.5) | 222 (78.7) | 62 (69.7) | |

| Active smoking | 48 (12.9) | 34 (12.1) | 14 (15.7) | P = .37 |

| Diabetes | 46 (12.4) | 29 (10.3) | 17 (19.1) | P = .041 |

| Hypertension | 101 (27.2) | 62 (22.0) | 39 (43.9) | P = .0001 |

| GERD c | 98 (26.4) | 29 (10.3) | 69 (77.5) | P = .0001 |

Proton pump inhibitor.

Standard deviation.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

3.1. Overall incidence and duration of symptoms

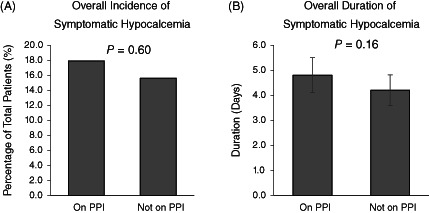

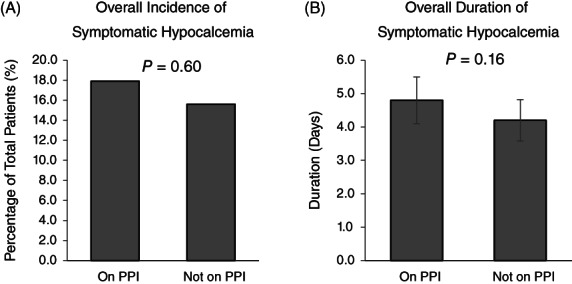

Sixty of the 371 patients (16.2%) developed symptomatic hypocalcemia. The average duration of symptoms was 4.3 days (SD 3.77). Eighty‐nine of 371 (24.0%) were on a proton pump inhibitor at the time of surgery. Of those patients, 16 (18.0%) patients developed symptomatic hypocalcemia, with an average duration of 4.8 days (SD 2.8). Of the 282 patients not on a PPI, 44 (15.6%) developed symptomatic hypocalcemia, with an average duration of 4.2 days (SD 4.1). There was no statistical significant difference in incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia (P = .63) or duration of symptoms (P = .16) between the two groups (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overall incidence, A, and duration, B, of symptomatic hypocalcemia between those taking and those not taking proton pump inhibitors (PPI) at the time of surgery

3.2. Incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia in patients with low PTH

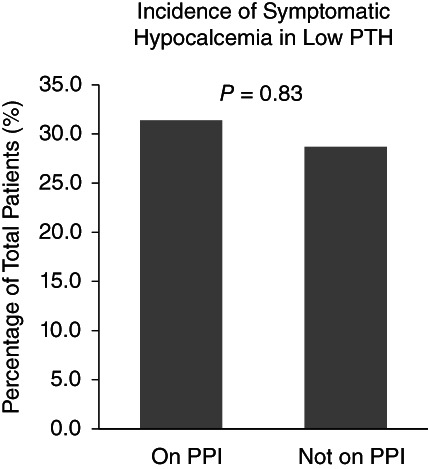

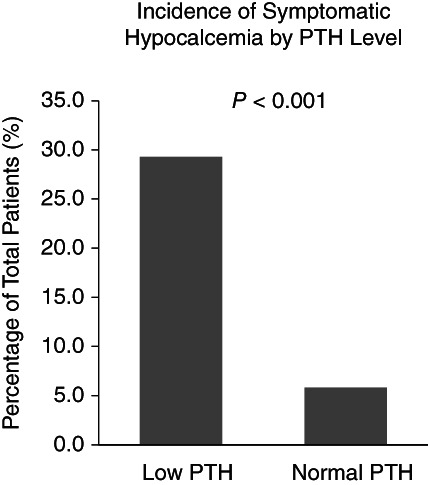

One‐hundred sixty‐four (44.2%) of all patients had a low postoperative PTH (defined as PTH < 12 pg/mL). Of those patients, 35 were on a PPI. Eleven of these 35 (31.4%) developed symptomatic hypocalcemia, while 37 of the remaining 129 (28.7%) not on a PPI developed symptomatic hypocalcemia (P = .83) (Figure 2). Of the 207 patients with normal PTH (≥12 pg/mL), 12 (5.8%) developed symptomatic hypocalcemia. This difference in incidence between those with normal and those with low PTH was found to be statistically significant (P < .0001), with a higher incidence in those with low PTH (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia in patients with low parathyroid hormone (PTH) between those taking and those not taking proton pump inhibitors (PPI) at the time of surgery

FIGURE 3.

Incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia based on postoperative parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels

3.3. Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis controlling for age revealed a significant association of age to incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia (P = .0008), with increasing age associated with lower incidence of symptoms. However, there was still no difference between those taking and those not taking PPIs (P = .59). With regards to duration of symptoms, age was not a predictor of increased duration (P = .22).

3.4. Emergency department visits

In the postoperative period, six of 282 patients (2.1%) not taking a PPI had an emergency department (ED) visit, while two of the 89 patients (2.3%) taking a PPI had an ED visit (P = .68). All visits were related to symptomatic hypocalcemia.

4. DISCUSSION

Proton pump inhibitors are one of the most ubiquitous medications in the world—popular for their ability to combat gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcers. 1 , 3 However, in recent years, the adverse effects of long‐term PPI use are becoming more evident. 4 Potential consequences include drug‐drug interactions, decreased intestinal absorption of essential vitamins and minerals, and increased risk of infections. 4 Although the specific mechanisms by which these effects occur are uncertain, it is thought that they are associated with decreased gastric acidity, impairing pH‐dependent absorption of several nutrients, including calcium. 4

Iatrogenic injury or removal of the parathyroid glands is a known complication of thyroidectomy, which may result in hypocalcemia. 9 This study sought to determine whether perioperative PPI use was associated with increased risk of symptomatic hypocalcemia and/or longer duration following thyroidectomy.

Although previous reports that PPIs decrease calcium absorption, this study did not observe any statistically significant difference in incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia following thyroidectomy in patients taking PPIs and those who were not. This held true for the subset of patients with low postoperative PTH levels, who are at higher risk of developing symptoms. Furthermore, for patients who developed symptomatic hypocalcemia, there was no statistically significant difference in duration of symptoms between those taking and those not taking PPIs. Not surprisingly, those with low postoperative PTH levels were more likely to develop symptomatic hypocalcemia than those who had normal postoperative PTH levels.

In a recent retrospective chart review, Young et al found that patients taking PPIs at the time of thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy were 1.81 times more likely to require evaluation in the ED compared to those not taking a PPI at the time of surgery. 10 The most common reason for ED evaluation in that study was paresthesias, however, there was no correlation with PPI use and paresthesias or electrolyte abnormalities. The rate of ED evaluation was 11% in that patient population, with 61% of those visits occurring after total thyroidectomy. This is much higher than the rate of 2.2% that was observed in this study. Additionally, there was not any statistically significant difference in rate of ED evaluation between those taking and those not taking PPIs at the time of surgery. The routine use of both calcitriol and calcium carbonate in patients with low postoperative PTH levels may be a mitigating factor even despite the concern for PPI induced malabsorption.

In this study, there was an association with age and symptomatic hypoparathyroidism, with increasing age associated with lower incidence of symptoms. A 2018 American Thyroid Association Surgical Affairs Committee Statement has listed several risk factors for iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism after thyroid surgery, but younger age is not included. 11 Further literature review of more recent articles related to postoperative hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia has also not showed age as a risk factor. The authors do not have an explanation for this finding but note that further inquiry into the subject may be warranted.

One limitation to this study is the retrospective nature. In particular, assessing the incidence and duration of symptomatic hypocalcemia via chart review assumes that patients' symptoms were consistently and completely documented. Determining use of PPI was based on patients' medication lists, but whether the medication was actually being consumed perioperatively cannot be confirmed. Another important consideration is that PPI use can cause hypomagnesemia, a known risk factor for hypocalcemia. 8 Preoperative magnesium levels were not available for this study and therefore could not be controlled for. Although a prospective cohort study would be ideal to capture this information more accurately, it would be logistically challenging; to determine a 1 day difference in mean duration of symptoms with 80% power, approximately 500 patients with symptomatic hypocalcemia would need to be recruited. This could be feasible, although it may require a multi‐institutional approach. Another limitation of this study is lack of generalizability as certain patients were excluded from this analysis. In particular, those found to have permanent hypoparathyroidism were not included. While clinicians can have a sense of who is at higher risk of permanent hypoparathyroidism based on intraoperative events, this is not known in the immediate postoperative period. In theory, these patients could be more prone to the effects of malabsorption of calcium that PPIs can have.

5. CONCLUSION

Patients on PPIs developed symptomatic hypocalcemia after total or completion thyroidectomy at a similar rate and for a similar duration as their non‐PPI counterparts. While the decision to continue PPI perioperatively should be made on a case‐by‐case basis, our data suggest that patients may be counseled to continue their PPI at the time of surgery without increased risk of symptomatic hypocalcemia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no financial or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Shelly Naud, PhD of the University of Vermont for her work on the statistics for this project.

Gerges D, Grohmann N, Trieu V, Brundage W, Sajisevi M. Effect of PPIs on symptomatic hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2021;6:150–154. 10.1002/lio2.515

Meetings: Poster at the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA, USA. September 17, 2019.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1. Naunton M, Peterson GM, Deeks LS, Young H, Kosari S. We have had a gutful: the need for deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(1):65‐72. 10.1111/jcpt.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999‐2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818‐1831. 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spechler SJ. Proton pump inhibitors what the internist needs to know. Med Clin N Am. 2019;103:1‐14. 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eusebi LH, Rabitti S, Artesiani ML, et al. Proton pump inhibitors: risks of long‐term use. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(7):1295‐1302. 10.1111/jgh.13737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toh JWT, Ong E, Wilson R. Hypomagnesaemia associated with long‐term use of proton pump inhibitors. Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;3(3):243‐253. 10.1093/gastro/gou054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zaya NE, Woodson G. Proton pump inhibitor suppression of calcium absorption presenting as respiratory distress in a patient with bilateral laryngeal paralysis and hypocalcemia. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89(2):78‐80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20155676. Accessed January 20, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Recker RR. Calcium absorption and achlorhydria. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(2):70‐73. 10.1056/NEJM198507113130202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stack BC, Bimston DN, Bodenner DL, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology disease state clinical review: postoperative hypoparathyroidism—definitions and management. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(6):674‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caglià P, Puglisi S, Buffone A, et al. Post‐thyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism, what should we keep in mind? Ann Ital Chir. 2017;6:371‐381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young WG, Succar E, Hsu L, Talpos G, Ghanem TA. Causes of emergency department visits following thyroid and parathyroid surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(11):1175‐1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Orloff LA, Wiseman SM, Bernet VJ, et al. American thyroid association statement on postoperative hypoparathyroidism: diagnosis, prevention, and management in adults. Thyroid. 2018;28(7):830‐841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]