Abstract

Purpose

HIV research among transgender and gender nonbinary (TGNB) people is limited by lack of gender identity data collection. We designed an EHR-based algorithm to identify TGNB people among patients living with HIV (PLWH) when gender identity was not systematically collected.

Methods

We applied EHR-based search criteria to all PLWH receiving care at a large urban health system between 1997–2017, then confirmed gender identity by chart review. We compared patient characteristics by gender identity and screening criteria, then calculated positive predictive values (PPVs) for each criterion.

Results

Among 18,086 PLWH, 213 (1.2%) met criteria as potential TGNB patients and 178/213 were confirmed. PPVs were highest for free-text keywords (91.7%) and diagnosis codes (77.4%). Verified TGNB patients were younger (median 32.5 vs. 42.5 years, p<0.001) and less likely to be Hispanic (37.1% vs. 60.0%, p=0.031) than unverified patients. Among verified patients, 15% met criteria only for prospective gender identity data collection and were significantly older.

Conclusion

EHR-based criteria can identify TGNB PLWH, but success may differ by ethnicity and age. Retrospective vs. intentional, prospective gender identity data collection may capture different patients. To reduce misclassification in epidemiologic studies, gender identity data collection should incorporate an intersectional framework and be systematic and prospective.

Keywords: transgender persons, HIV, electronic health records, algorithms

Introduction

Transgender and gender nonbinary (TGNB) people (i.e., individuals whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth) make up an estimated 0.6% of the U.S. population.(1) TGNB people experience profound health disparities, including high rates of HIV infection. Transgender women (hereafter referred to as trans-women) of color are most impacted, with an estimated 44% prevalence of HIV infection among Black/African-American trans-women and 26% among Hispanic/Latina trans-women.(2) Information about HIV among trans-men (i.e., assigned female at birth, with gender identity of male or other than female) is lacking, though some studies indicate trans-men who have sex with cisgender (i.e., individuals whose gender identity is the same as their sex assigned at birth) men may be at elevated risk.(1, 2)

Despite such disparities, research about TGNB people has been limited by lack of gender identity data collection.(3) Historically, health systems have not collected gender identity information and have misclassified TGNB people as cisgender.(4, 5) Among people living with HIV (PLWH)—a population in which gender identity data collection is arguably better than most—TGNB people are often conflated with men who have sex with men or excluded from studies altogether.(4) Misclassification of TGNB people significantly impairs further understanding of TGNB health disparities and interventions.

Electronic health records (EHR) data have been used to capture other hard-to-identify populations in HIV research.(6–9) Several studies have identified TGNB people from EHR data, but have done so in largely White populations and without considering HIV serostatus.(10–12) Given that HIV has disproportionately impacted TGNB communities, particularly communities of color, throughout the HIV epidemic, gender identity documentation may vary among PLWH. HIV providers may be more experienced with TGNB patients and some HIV surveillance systems have added explicit gender identity data fields.(13, 14) Such differences in care and overrepresentation of TGNB people among PLWH may mean that optimal EHR-based methods for identifying TGNB people differ among PLWH. The current study aimed to develop an algorithm using routinely collected EHR data to identify TGNB patients among PLWH at a large urban health system.

Methods

Setting

An estimated 0.8% of New York City’s nearly 8.4 million residents are TGNB.(15, 16) The prevalence of TGNB individuals among PLWH is unknown. However, of PLWH seeking services at sites supported by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute in New York City 4.4% were classified as transgender between July, 2014-December, 2016 (Ronald Massaroni, AIDS Institute Reporting System, 02/2019).

The Bronx is one of New York City’s five boroughs and has a high prevalence of HIV infection, estimated at 2.0%.(15) Twenty-seven percent of Bronx residents live below the poverty line, 44% identify as Black or African-American, 56% identify as Hispanic, 35% were born outside of the US, and 59% speak a language other than English at home. (19) The Montefiore Health System (MHS) serves Bronx and Westchester counties and is the largest health system in the Bronx. This study is limited to Bronx-based locations, including four hospitals and >50 ambulatory sites.

Dedicated HIV care within MHS is provided at 10 primary care centers, an infectious diseases clinic, three substance treatment programs, and an adolescent clinic. As Ryan White-funded clinics, these sites are required to report demographic, behavioral, and clinical data to the New York State Department of Health’s AIDS Institute Reporting System (AIRS). At the time of study completion, MHS offered no formal TGNB-specific programming.

Electronic health records (EHR) at Montefiore

MHS has utilized three EHR systems since EHR adoption in 1997, most recently, Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI). Following EHR implementation, MHS acquired new sites, some with limited EHR data. For instance, labs, prescriptions, and scanned documents (e.g., name change documentation) were available from some sites, while progress notes were not. With each new EHR system, records from the previous system were integrated into the newer one. With these changes, some standardized fields (e.g., fields for “sex at birth” and “gender identity”) were converted to free-text. This evolution of EHR documentation mirrors many established institutions and reflects a real-world context.

Data source

The Einstein-Rockefeller-CUNY Center for AIDS Research (CFAR)’s Clinical Cohort Database includes information for all MHS patients with laboratory-confirmed HIV infection or uninfected status since 1997. (20, 21) The database contains over 18,000 HIV-infected and 350,000 HIV-uninfected patients. MHS’s EHR data are merged with data collected at Ryan White-funded clinics for mandated reporting to AIRS. Data include demographic, diagnostic, laboratory, prescription, and visit information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all patients with documented HIV infection between 1997 and 2017. (21) Patients were excluded if upon chart review they had no available EHR data. Twenty-three patients (9.7% of potential TGNB patients) were excluded.

Identifying TGNB patients

To identify TGNB patients, we first selected EHR-based screening criteria, then applied the criteria to EHR data of all eligible patients. For patients meeting at least one screening criterion, we confirmed TGNB status through manual chart review with application of a reference standard. Lastly, we refined our screening criteria via review of a 2% random sample of patients not meeting screening criteria.

Selection of screening criteria

The research team, composed of gender-affirming care providers, developed screening criteria based on literature review and clinical experience (Table 1). Feedback on screening criteria was solicited from a multidisciplinary group of over 50 MHS providers caring for TGNB patients. Changes to criteria were made via consensus among the research team. Criteria fell into four categories: 1) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) diagnosis codes; 2) gender-affirming medications (e.g., concurrent male gender marker and estrogen prescription); 3) free-text keywords, and 4) gender identity variables (e.g., yes/no field for “transgender”) systematically reported to receive Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grant funding.

Table 1.

Screening Criteria Used to Identify Potential Transgender/Gender Nonbinary Patients

| ICD-9 and 10-CM codesa | Gender marker and medications | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 302.50: Trans-sexualism with unspecified sexual history 302.51: Trans-sexualism with asexual history 302.52: Trans-sexualism with homosexual history 302.53: Trans-sexualism with heterosexual history 302.85: Gender identity disorder in adolescents or adults F64.0: Transsexualism, transgender, gender dysphoria F64.1: Gender identity disorder in adolescence or adulthood F64.2: Gender identity disorder of childhood F64.8: Other gender identity disorders F64.9: Gender identity disorder, unspecified Z87.890: Personal history of sex reassignment |

Male gender marker and estrogens/progestins Estrogen or progesterone & spironolactone 200mg Estrogen or progesterone and finasteride Female gender marker and testosterone HIV funding-related variables Transgender on HIV care form Discrepant AIRSb sex and institutional EHR sex Discrepant AIRS sex assigned at birth and gender identity |

Gender dysphoria Gender non-conforming Gender transition Genderqueer Gender reassignment Female to male FTMc Male to female MTF Sex reassignment Transgender Transsexual Transvestite |

International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification codes

AIRS = New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Reporting System – Includes data collection required for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grant funding

Eliminated prior to chart review

Application of screening criteria and reference standard

Screening criteria were applied to EHR data for all eligible patients. We classified patients meeting any screening criteria as potential TGNB patients. One research team member reviewed all available EHR data for potential TGNB patients. Because no gold standard exists to verify TGNB identity via EHR, we developed the following a priori reference standard: 1) explicit provider documentation of TGNB status, or 2) discrepant sex assigned at birth and gender identity in standardized fields at more than one visit. A third criterion was later added due to limited EHR data for some patients; name change documentation with labs or medications consistent with gender-affirming care was felt sufficient to confirm TGNB identity. Two patients were verified in this way. We considered patients TGNB if they met the reference standard at least once. Questions about meeting reference standard criteria were resolved by consensus with a second reviewer (VP).

Refinement of screening criteria

Our screening criteria were developed by providers regularly caring for TGNB patients. These providers were therefore not representative of providers across the institution. To reduce bias and minimize false negatives, one researcher (JCB) manually reviewed a 2% (n=360) random sample of charts among confirmed HIV-infected patients not meeting TGNB screening criteria.

Ethical issues

Given widespread discrimination toward TGNB people, there is inherent risk in identifying TGNB patients. Fear of repercussions has limited data collection about TGNB communities, however, severe health disparities have been identified. Accurate investigation of such disparities is a necessary step toward addressing them. Given the potential to impact health disparities and increased recent efforts toward proactive gender identity data collection in healthcare settings, the research team believed the benefits of this study outweighed the risks.(22) To protect individuals in this study, no more than two people reviewed medical records for all potential TGNB patients. After completing chart reviews, medical record numbers and date of birth were deleted from the dataset. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albert Einstein College of Medicine; patient consent to access and use medical records was waived.

Data Analyses

We compared characteristics between groups by TGNB status and among groups by category of screening criteria met, using relevant bivariate analyses. We calculated positive predictive values (PPVs) for each category of screening criteria (e.g., ICD-9/10-CM codes) in two ways; first, for all patients meeting criteria within a category regardless of other criteria met (not shown in table); and second, for patients meeting criteria only within that category. For gender-affirming medications, we calculated the PPV first for the category overall, and then as two separate groups defined by feminizing vs. masculinizing medications. We calculated the percent of TGNB patients in the overall cohort per year, using all patients with HIV-related lab data available in a given calendar year. TGNB patients were counted as TGNB in every year they had lab data, regardless of when they were identified as TGNB. Statistical analysis was done using Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The overall cohort of patients with documented HIV infection between 1997 and 2017 (N=18,086) had a median age of 42 (IQR 34–49) on entry to care. Patients were majority Black non-Hispanic (41.8%) or Hispanic (35.6%). Most patients had public insurance at first encounter (74.4%).

Verification of TGNB status

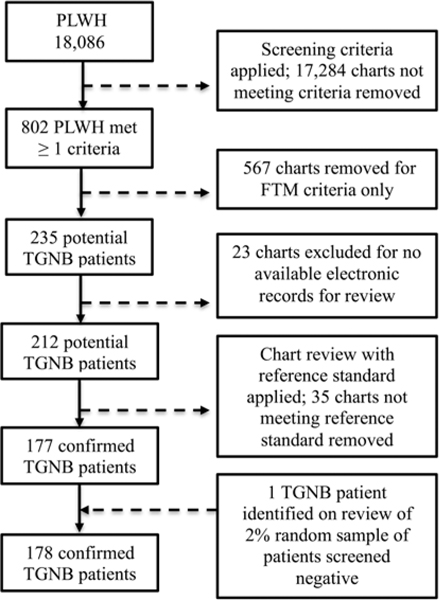

Among the 18,086 eligible patients, 802 met initial screening criteria (Figure 1). More than 70% of charts (n=576) screening positive met only the criterion for the free-text term, “FTM,” which was discovered to be an unrelated administrative code. Charts meeting only this criterion were removed, leaving 212 potential TGNB patients. From the 2% random sample of charts not meeting screening criteria, we identified one new TGNB person and one new free-text criterion (“gender transition”). We searched for the new criterion in the original pool of eligible patients and identified no further potential TGNB patients.

Figure 1:

Identification of transgender/gender nonbinary patients

TGNB = Transgender/gender nonbinary. PLWH = people living with HIV. 18,086 patients were eligible for the study. Screening criteria includes electronic health records-based criteria from four categories: ICD-CM 9/10 diagnosis codes, gender-affirming medication prescriptions, free-text keywords, and demographic information collected to receive Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grant funding. Criteria were searched for in EHR data of all eligible patients. “FTM” refers to a free-text screening criterion. Charts meeting only this criterion were removed.

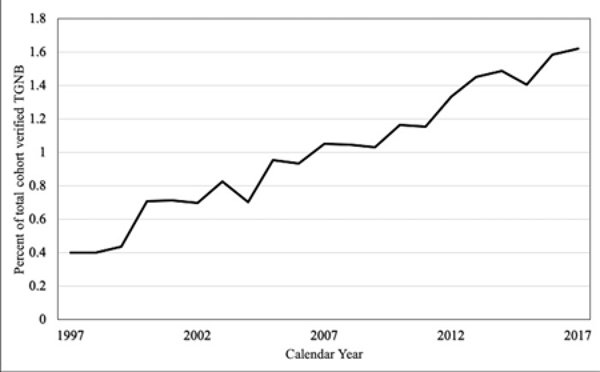

After chart review, we classified 178/213 (84%) of potential TGNB patients as verified TGNB. Reasons for screening positive without confirmation included: keywords not describing the patient (e.g., “MTF,” under sexual partners), erroneous or unexplained prescriptions, and documentation errors (e.g., clicking “female” instead of “male” from a drop-down menu). The percent of verified TGNB patients per year in the overall cohort increased over time from 0.4% in 1997 to 1.6% in 2017 (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Percent of cohort identified as transgender/gender nonbinary by calendar year

TGNB = Transgender/gender nonbinary. All eligible patients with HIV-related lab data available in a given calendar year were included in the analysis for that year. Patients confirmed TGNB were counted as TGNB in every year they had lab data, regardless of year identified as TGNB.

Among verified TGNB patients, 14.6% (n=31) were identified by ICD-9/10-CM codes alone, 9% (n=19) by gender-affirming medications alone, 5.7% (n=12) by free-text key terms alone, 19.8% (n=42) by HIV-funding-related gender identity data alone, and 50.1% (n=108) by criteria from multiple categories (Table 2). Verified TGNB patients identified by HIV funding-related data alone were significantly older than patients identified otherwise (median 38 vs 32 years, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Results of Transgender/Gender Nonbinary Status Validation by Mode of Screening

| Mode of ascertainment | Total meeting criteria n (%) | Meeting only this criteria n (%) | Verified TGNBa n (%) | Not verified TGNB n (%) | PPV b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9- and 10-CM diagnosis codesc | 125 (59.0) | 31 (14.6) | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | 77.4 |

| Gender-affirming medications | 85 (39.9) | 19 (9.0) | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | 52.6 |

| Feminizing | 80 (37.7) | 15 (7.0) | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | 66.7 |

| Masculinizing | 4 (1.9) | 4 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (100.0) | 0 |

| Free-text keywords | 57 (26.8) | 12 (5.7) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 91.7 |

| HIV funding-related demographics | 131 (61.8) | 42 (19.8) | 26 (61.9) | 16 (38.1) | 61.9 |

| >1 of the above | 108 (50.1) | n/a | 107 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | 99.1 |

TGNB = transgender/gender nonbinary

PPV = positive predictive value

International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification

Positive predictive values (PPVs) for criteria from free-text keywords, ICD-9/10-CM codes, HIV funding-related gender identity data or gender-affirming medications were: 91.7%, 77.4%, 61.9% and 52.6%, respectively (Table 2). When considered separately, feminizing medication regimens had a PPV of 60%, while no patients meeting only masculinizing medication criteria were confirmed TGNB. The term, “transgender” made up over half of all keyword appearances and had a PPV of 95.9% for all patients meeting this criterion and 88.9% for patients meeting only this criterion. No patients met criteria for the keywords “gender non-conforming” or “genderqueer.” For patients meeting more than one category of screening criteria (n=108), regardless of which categories, the PPV was >99%.

Differences between verified TGNB patients and unverified potential TGNB patients

Table 3 displays characteristics of verified TGNB patients (N=178) vs those who screened positive but were unverified (N=35). Among verified TGNB patients, 177 of 178 (99.4%) were assigned male at birth, compared to 21 of 36 (58.3%) of patients not verified TGNB. Verified TGNB patients compared to those not verified were younger at entry to care (median 32.5 years, IQR 25–39 vs. median 42.5, IQR 34–49, p<0.001) and less likely to be Hispanic (37.1% vs. 60.0%, p=0.03).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Patients by Transgender/Gender Nonbinary Screening StatusScreened Positivea

|

Screened Positivea |

Screened negative (n=17,850) n % | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed TGNBb (n=178) n % | Not confirmed TGNB (n=35) n % | |||

| Age at entry to care, years (median, IQR)c | 32.5 (25–39) | 42.5 (34–49) | 42 (34–49) | <0.001 |

| Male sex assigned at birth | 177 (99.4) | 21 (58.3) | 10,626 (59.5) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.031 | |||

| Hispanic | 66 (37.1) | 21 (60.0) | 6,247 (35.0) | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 80 (44.9) | 9 (25.7) | 7,323 (41.0) | |

| Otherd | 8 (4.5) | 0 | 945 (5.3) | |

| Unknown | 24 (13.5) | 5 (14.3) | 3,335 (18.7) | |

| Insurance at first visit | 0.006 | |||

| Public | 142 (79.8) | 26 (74.3) | 12,229 (68.5) | |

| Commercial | 9 (5.1) | 4 (11.4) | 1,905 (10.7) | |

| Self-pay | 23 (12.9) | 4 (11.4) | 1,444 (8.1) | |

| Other/unknown | 4 (1.8) | 1 (2.9) | 2,272 (12.7) | |

Excludes 23 patients who screened positive, but had no chart data for review

TGNB = transgender/gender nonbinary

IQR = Interquartile range

Includes: White, Asian, Native American, Native Alaskan, Asian/Pacific Islander

Differences between verified TGNB patients and patients not meeting screening criteria

Verified TGNB patients (N=178) were younger than patients who screened negative for TGNB status (N=17,850) (median 32.5 years, IQR 25–39 vs 42 years, IQR 34–49, p<0.001). Verified TGNB patients were significantly more likely to have public (69.8% vs 68.5%) or no insurance (12.9% vs 8.1%) and less likely to have commercial insurance (5.1% vs 10.7%, p<0.001) than patients not meeting screening criteria. These patient groups were not significantly different in terms of race/ethnicity.

Discussion

In this study, we identified TGNB patients among PLWH using routinely collected EHR information. We showed that criteria for such identification may differ by age and ethnicity. Our findings also indicate that different groups of TGNB people may be captured through intentional, prospective gender identity data collection versus retrospective EHR-based data collection.

Overall, our algorithm had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 84%. Similar to prior studies, our findings revealed relatively high PPVs for ICD codes and free-text keywords, at 77.4% and 91.7% respectively (Table 2).(10–12) Also consistent with prior studies, however, we were unable to confirm TGNB identities for over 22% of patients meeting ICD codes alone. (10, 12) Lack of confirmatory data may be explained by poor documentation (i.e., little overall free-text documentation), erroneous ICD codes, or conflation of gender identity and sexuality (e.g., use of “gender dysphoria” for homophobia-related stress). Studies relying on ICD codes alone, such as use of administrative claims data, may misclassify a large portion of individuals and should consider analyzing unverified patients identified in this way as a separate group.

Our study also uncovered significant differences in algorithm performance by ethnicity. Patients who screened positive for TGNB identity, but were unconfirmed were significantly more likely to be Hispanic (60.0%) than patients who were confirmed (37.1%) or those who screened negative (35.0%). Given a setting in which 35% of the population is born in another country and 59% of residents speak a language other than English, this finding highlights the need for further investigation about gender identity data collection among TGNB people speaking languages other than English and TGNB immigrant communities. (23)

Our algorithm also performed poorly among transmasculine and gender nonbinary individuals. We identified only one transmasculine person living with HIV over a 20-year time span at the largest HIV provider in the Bronx, while New York State AIDS Institute supported sites reported six transmasculine PLWH in the borough in under two years (Ronald Massaroni, AIDS Institute Reporting System, 02/2019). It may be that transmasculine people are less often identified as TGNB during clinical encounters and/or identified in ways not included in our screening criteria. More research is needed to understand how to best identify transmasculine people from administrative data.

We identified no patients using the keywords “gender non-conforming” or “genderqueer.” However, over one-third of TGNB people nationally report nonbinary gender identities, most commonly among young trans-people—the demographic most at risk for HIV acquisition. Ongoing research is needed to understand optimal means of capturing data for nonbinary identified people.(24)

Our study also revealed differences in TGNB classification with use of retrospective vs. intentional, prospective gender identity data collection. Of verified TGNB patients in our study, 15% were identified by only intentional, prospectively collected HIV funding-related gender identity data. These patients would not have been identified via administrative claims data or any of the previously published retrospective EHR-based algorithms. This variable may serve as a proxy for intentional gender identity data collection, highlighting the likelihood of substantial misclassification without such proactive measures. Additionally, patients identified in this way were significantly older on entry to care than other patients (median 38 vs 32, p<0.001). Less clearly defined differences in healthcare utilization may also exist. Failure to identify this group of TGNB people may introduce differential misclassification, leading to biased estimates. These findings underscore the need for improved prospective and systematic gender identity data collection among all patients. Best practices for collecting gender identity data have been developed using a two-step method: (1) sex assigned at birth, and 2) gender identity. (25–27) Implementation of such data collection, however, remains highly inconsistent.(5, 14)

Overall, despite our multi-faceted approach to identifying TGNB patients, <1% (n=178) of the cohort of PLWH were identified as TGNB. This number is smaller than expected, based on the estimated 0.8% prevalence of TGNB individuals in New York City and high rates of HIV infection impacting TGNB communities, particularly TGNB communities of color. This discrepancy may represent ascertainment bias. Transphobic stigma among HIV providers has been identified as a barrier to effective HIV care among TGNB people and likely also deters disclosure of TGNB identities in these settings.(17, 18) Anticipated transphobia may also lead to disparate HIV care engagement.(19, 20) HIV surveillance data from New York City have shown delayed linkage to care among trans-women newly diagnosed with HIV.(32)

The percentage of TGNB patients identified in the cohort grew over time from 0.4% in 1997 to 1.6% in 2017. This trend may indicate improved gender identity data collection with changing social awareness. However, the growing rate may also reflect trends in the larger HIV epidemic. The World Health Organization has recognized TGNB people as a key population in which the incidence of HIV has increased while declining or stabilizing in the general population.(21, 22) Accurate gender identity data collection that minimizes misclassification will be an essential step toward fully understanding the scope of HIV and additional health outcomes among TGNB communities.

Limitations

Because we identified gender identity through retrospective chart review, limited by providers’ knowledge and documentation choices, our study likely has false negatives. We also recognize that provider documentation may not reflect the complete spectrum of gender identities among patients in the study. Our study was also limited to EHR data from one health system. Although there are undoubtedly similarities across institutions, different EHR systems and local institutional and TGNB community norms may impact broader applicability. Additionally, our study did not include gender-affirming surgery data. Future studies might benefit from use of gender-affirming procedure codes.

Conclusions

TGNB patients can be identified from routinely collected EHR data among PLWH. Criteria for doing so may differ among specific gender identity groups and by other patient characteristics, including ethnicity and age. Different groups of TGNB people may be captured by retrospective versus intentional, prospective gender identity data collection. Future efforts to capture gender identity data should maintain an intersectional framework, accounting for all aspects of a person’s identity, and include implementation of systematic, prospective gender identity data collection.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patients in this study; the Bronx Gender Equity and Wellness Advisory Board, for contextualizing findings; Martin Packer, for assistance in obtaining and organizing data; Drs. Robert Beil, Olivia Low and Daniel Schoenfeld, for completion of chart review; and Ronald Massaroni of the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, for providing data.

Funding Information

This work was supported in part by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) Einstein-Montefiore CTSA [Grant Number UL1TR002556] and the Einstein-Rockefeller-CUNY Center for AIDS Research [P30-AI-124414], which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHBL, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC and OAR. V.V.P. was supported by K23-MH-102118. D.B.H. was supported by K01-HL-137557. No funding source was involved in the study design; data collection, analysis or interpretation; manuscript preparation, or decision to submit for publication.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AIRS

New York State Department of Health’s AIDS Institute Reporting System

- CFAR

Center for AIDS Research

- EHR

Electronic health records

- ICD-9/10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MHS

Montefiore Health Systems

- PLWH

People living with HIV

- PPV

Positive predictive values

- TGNB

Transgender and gender nonbinary

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statements

No competing financial interests exist for any of the study’s authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reisner SL, Murchison GR. A global research synthesis of HIV and STI biobehavioural risks in female-to-male transgender adults. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(7–8):866–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowniak S, Chesla C, Rose CD, Holzemer WL. Transmen: the HIV risk of gay identity. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(6):508–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reisner SL C, et al. “Counting” transgender and gender-non-conforming adults in health research: recommendations from the Gender Identity in US Surveillance Group. Transgender Studies Quarterly. 2015;2(1):34–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poteat T, German D, Flynn C. The conflation of gender and sex: Gaps and opportunities in HIV data among transgender women and MSM. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(7–8):835–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutsch MB, Keatley J, Sevelius J, Shade SB. Collection of gender identity data using electronic medical records: survey of current end-user practices. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(6):657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross J, Hanna DB, Felsen UR, Cunningham CO, Patel VV. Emerging from the database shadows: characterizing undocumented immigrants in a large cohort of HIV-infected persons. AIDS Care. 2017;29(12):1491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menza TW, Levine K, Grasso C, Mayer K. Evaluation of 4 Algorithms to Identify Incident Syphilis Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men Engaged in Primary Care. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46(4):e38–e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levison J, Triant V, Losina E, Keefe K, Freedberg K, Regan S. Development and validation of a computer-based algorithm to identify foreign-born patients with HIV infection from the electronic medical record. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(2):557–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakower DS, Gruber S, Hsu K, Menchaca JT, Maro JC, Kruskal BA, et al. Development and validation of an automated HIV prediction algorithm to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e696–e704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blosnich JR, Cashy J, Gordon AJ, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Brown GR, et al. Using clinician text notes in electronic medical record data to validate transgender-related diagnosis codes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(7):905–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenfeld JM, Gottlieb KG, Beach LB, Monahan SE, Fabbri D. Development of a Natural Language Processing Algorithm to Identify and Evaluate Transgender Patients in Electronic Health Record Systems. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 2):441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roblin D, Barzilay J, Tolsma D, Robinson B, Schild L, Cromwell L, et al. A novel method for estimating transgender status using electronic medical records. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(3):198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reporting N-AIDSD. Guide to the 2018 RSR (Ryan White HIV/AIDS Services Report). 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen A, Katz KA, Leslie KS, Amerson EH. Inconsistent Collection and Reporting of Gender Minority Data in HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infection Surveillance Across the United States in 2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S4):S274–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HIV Surveillance Annual Report. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health NYSDo. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Selected Demographics and Health Indicators New York State Adults, 2014‐2016. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; 2017. Report No.: 1806. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siskind RL, Andrasik M, Karuna ST, Broder GB, Collins C, Liu A, et al. Engaging Transgender People in NIH-Funded HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72 Suppl 3:S243–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosenko KA. Contextual influences on sexual risk-taking in the transgender community.J Sex Res. 2011;48(2–3):285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizuno Y, Frazier EL, Huang P, Skarbinski J. Characteristics of Transgender Women Living with HIV Receiving Medical Care in the United States. LGBT Health. 2015;2(3):228–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golub SA, Gamarel KE. The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(11):621–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. Geneva,; 2014. Report No.: 9789241507431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations - 2016 Update. Geneva,; 2016. Report No.: 9789241511124. [Google Scholar]