Abstract

Background

Vulvar aphthous ulcers have been associated with various prodromal viral illnesses. We describe the case of an adolescent girl who developed vulvar aphthous ulcers during infection with Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

Case

A 19-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with cough, sore throat, fevers, and rash, and tested positive for COVID-19. She re-presented 2 days later with vulvar pain and was found to have a vulvar aphthous ulcer. She was admitted for pain control and treated with oral steroids. Improvement in her vulvar pain was noted, along with resolution of fevers, cough, and rash.

Summary and Conclusion

This case illustrates the novel association of COVID-19 with vulvar aphthous ulcers in adolescents. Use of oral steroids for symptomatic management of COVID-19 led to rapid clinical improvement.

Key Words: vulvar aphthous ulcers, COVID-19, clinical presentation

Introduction

Non−sexually acquired genital ulcers (NSGU), also referred to as vulvar aphthous ulcers, were initially described in 1913 by Lipschutz as a phenomenon of sudden-onset, self-limited vulvar ulcers in non−sexually active girls with systemic signs of infection.1 , 2 Non−sexually transmitted genital aphthous ulcers are uncommon,2 but the exact prevalence has not been determined.

Acute genital ulceration from NSGU is a clinical diagnosis and requires the exclusion of other etiologies, including sexually transmitted infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), Behçet's syndrome and autoimmune bullous diseases. Historically, aphthous ulcers are misdiagnosed and often extensively evaluated.2 , 3 The pathogenesis for vulvar aphthosis is thought to be attributable to a nonspecific reactive inflammatory response to a systemic illness.3 Several precipitating infectious diseases have been documented in the literature, including salmonellosis, mononucleosis, viral gastroenteritis, viral upper respiratory tract infection (URI), and influenza.2

COVID-19 has been shown to affect multiple organ systems, including respiratory, enteric, hepatic, and neurologic systems. COVID-19 has been linked to oral aphthous ulcers in the dermatology literature, which is thought to be due to the cytokine storm and systemic inflammatory response produced with this infection.4 Little is known, however, about the effect of the novel Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 virus in connection with vulvar ulcers in adolescents.

No standard treatment regimen exists for vulvar aphthous ulcers. Proposed treatment options include local or systemic pain control, topical or systemic steroids, and reassurance.5 There is some evidence to suggest that oral steroids are beneficial in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to reduce mortality; however meta-analyses yielded mixed results, and more research is needed to determine the effect on symptom management.6

Here we review the case of a patient infected with COVID-19 who presented with acute vulvar pain and inability to void. To our knowledge, this is the first case report to describe vulvar aphthous ulcers associated with a symptomatic COVID-19 infection in an adolescent. Our objectives are to highlight the clinical features of this case, the treatment regimen used, and the patient response.

Case

A 19-year-old girl presented to the emergency department (ED) with vulvar pain, severe pain with voiding, and skin sloughing of the vulva. Two days prior, she had presented to the ED with complaints of a whole-body erythematous, non-raised rash, malaise, cough, and sore throat, and was diagnosed with COVID-19 by nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction. She was discharged home at that time with supportive care measures including oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and topical hydrocortisone cream to treat her rash. After discharge, she developed severe vulvar pain and therefore re-presented to the ED. Her medical history was significant for bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety, but was negative for autoimmune or inflammatory conditions. Her last sexual contact was 1 week prior to presentation, with her only lifetime male partner. Neither she nor her partner reported any prior history of genital ulcer disease. She had a subdermal implant for contraception, reported inconsistent condom use, but did endorse using condoms with her last sexual encounter.

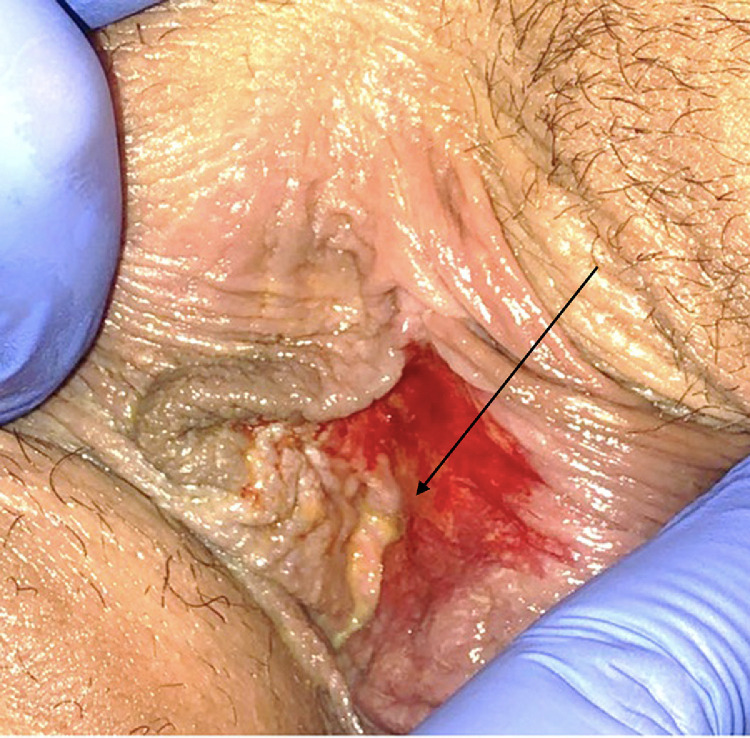

On physical examination, she was afebrile, and all other vital signs were normal, including normal oxygen saturation on room air. She appeared in mild distress due to pain. On genital examination, she was noted to have diffuse erythema of bilateral labia minora, with a 1 × 2-cm-deep ulcer located on the inner aspect of the left labia minora. The ulcer was noted to be well demarcated, with a fibrinous exudate sloughing from the surface; no eschar was present. A photograph was obtained but, given the degree of patient discomfort, patient positioning was limited, and the image was able to capture skin sloughing but not the well-demarcated ulcer in the area designated by the arrow in Fig. 1 . Oropharyngeal examination findings were significant for posterior oropharyngeal erythema, but no lesions or exudate were noted.

Fig. 1.

Initial presentation vulva demonstrating erythema and skin sloughing. Arrow denotes area of ulceration, not well visualized.

Laboratory evaluation was significant for persistent COVID-19, normal complete blood count, and negative sexually transmitted infection screening including testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Viral testing of the lesion for HSV was not done due to patient discomfort with examination and low suspicion given the appearance consistent with NSGU. However, IgG serologies for HSV-1 and HSV-2 were obtained at her follow-up appointment 2 weeks after discharge. HSV-1 IgG was positive and HSV-2 IgG was negative. The patient did confirm a history of recurrent oral ulcerations and denied any history of previous genital ulcerations.

Clinical history and genital examination findings were consistent with vulvar aphthosis in response to systemic COVID-19 infection. The patient was admitted for pain control and started on an oral pain regimen including scheduled acetaminophen and ibuprofen, with oxycodone for breakthrough pain, as well as topical lidocaine gel and petrolatum barrier cream. For dysuria, it was recommended that she void in the bathtub; an indwelling Foley catheter was not required. For her COVID-19 symptoms of cough and sore throat, she was started on dexamethasone 6 mg oral daily for 7 days. She did not receive additional topical steroids for the vulvar area. She was discharged on hospital day 2 with a continued pain regimen and a total of 7 days of oral dexamethasone.

She presented for follow-up appointment 2 weeks later, reporting significant improvement in her pain and dysuria. She was able to void normally and was no longer requiring any pain medications. She finished her 7-day course of dexamethasone. Her rash, cough, and sore throat had also resolved. Physical examination was significant for improvement in her left labial ulcer, with only a small area of granulation tissue noted in the area of previous ulceration (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Follow-up image demonstrating improvement in left labial ulcer. Arrow denotes area of new granulation tissue and resolving ulcer.

Summary and Conclusion

The typical presentation of vulvar aphthous ulcers includes acute onset of vulvar or genital pain, preceded by nonspecific viral symptoms.1 Dysuria is also common due to irritation caused by contact with urine at the ulcerated base. The classic appearance of a vulvar aphthous ulcer is a shallow ulcer, well-demarcated, typically greater than 1 cm, with overlying fibrinous exudate, and can occasionally present with symmetrical “kissing” lesions on the opposite labia.7 The mainstays of treatment include pain management, steroids, and supportive care.3

The patient in this case presented with findings typical for vulvar aphthosis, including a week of prodromal malaise, cough, rash, and sore throat, followed by acute-onset severe vulvar pain and dysuria. Upon review of the literature, there is 1 documented case of a vulvar aphthous ulcer in an adult patient after infection with Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Similarly, the patient was treated with oral steroids and achieved improvement in ulceration and pain reduction within 1 week of treatment initiation.8

The pathogenesis of vulvar aphthosis is thought to be due to a nonspecific inflammatory response to a systemic illness. Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus known to affect multi-organ systems through activation of a systemic inflammatory response.4 Given the systemic immune response, the link between vulvar aphthosis and COVID-19 has a plausible physiologic basis.

Although the initial management of vulvar aphthosis generally includes a regimen of pain control and steroids, there is limited evidence to support specific recommendations regarding oral versus topical steroids. In this patient, the decision to continue oral steroids was made because of the concurrent treatment of COVID-19 symptoms with an oral regimen. The patient achieved quick resolution of symptoms and was asymptomatic 2 weeks after initial presentation.

Upon review of the literature, there are case reports and retrospective reviews linking vulvar aphthosis to viral syndromes including Epstein−Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV); however, the treatment protocols and duration of symptoms vary. In a study population of 20 individuals with non−sexually transmitted vulvar ulcers, the average duration of pain from vulvar ulcers was 10 days, with 75% demonstrating healing of the ulceration within 21 days.7 In this same series, there was no single infectious agent identified as the precipitating viral illness; however, acute EBV or CMV infections were identified in 4 of the 20 patients studied.7 In another retrospective review, vulvar ulcers were associated with viral syndromes of gastroenteritis or upper respiratory tract infection in 6 of the 10 patients identified, with resolution of ulcers within several weeks, with most being treated with topical steroids.2

Although there are limited data directly comparing oral versus topical steroids as treatment for vulvar aphthosis, a retrospective review of 26 patients showed that 94% of the 17 patients treated with oral steroids achieved pain relief and healing of ulcers within 16 days.5 Proposed treatment algorithms include oral analgesia with NSAIDs and narcotics as needed, topical analgesia with lidocaine or compounded lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine (L.E.T) gel, and either topical or oral corticosteroids.7

In conclusion, this case highlights a novel association of COVID-19 infection with vulvar aphthosis in an adolescent. It has been recognized that vulvar aphthous ulcers occur in response to systemic EBV, CMV, and viral gastroenteritis,2 , 7 and now has been documented in response to coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Although both oral and topical steroid regimens have been used in the past to treat vulvar aphthosis, this case illustrates the use of oral steroids as a potentially superior regimen to treat both COVID-19 and the vulvar ulcerations.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

No funding was received for this case report

References

- 1.Farhi D., Wendling J., Molinari E., et al. Non–sexually related acute genital ulcers in 13 pubertal girls: a clinical and microbiological study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:38. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehman J., Bruce A., Wetter D., et al. Reactive nonsexually related acute genital ulcers: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farag Ahmed E.S. Nonsexually acquired acute genital ulceration: a commonly misdiagnosed condition. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2018;25:13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominguez-Santas M., Diaz-Guimaraens B., Fernandez-Nieto D., et al. Minor aphthae associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1022. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixit S., Bradford J., Fischer G. Management of nonsexually acquired genital ulceration using oral and topical corticosteroids followed by doxycycline prophylaxis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:797. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar S., Khanna P., Soni K.D. Are the steroids a blanket solution for COVID-19? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huppert J.S., Gerber M.A., Deitch H.R., et al. Vulvar ulcers in young females: a manifestation of aphthosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:195. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falkenhain-López D., Agud-Dios M., Ortiz-Romero P., et al. COVID-19-related acute genital ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e655. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]