Abstract

Objective

Although women in the field of biomedical informatics (BMI) are part of a golden era, little is known about their lived experiences as informaticians. Guided by feminist standpoint theory, this study aims to understand the impact of social change in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia- in the form of new policies supporting women and health technological advancements—in the field of BMI and its women informaticians.

Materials and Methods

We conducted semistructured telephone interviews with 7 women managers in the field of BMI, identified through LinkedIn. We analyzed interview transcripts to generate themes about their lived experiences, how they perceived health information technology tools, identified challenges that may hinder the advancement of the field, and explored the future of BMI from their perspectives. During our analysis, we utilized a feminist theoretical approach.

Results

Women managers in the field of BMI shared similar experiences and perspectives. Our analysis generated 10 themes: (1) career beginning, (2) opportunities given, (3) career achievements, (4) gender-based experiences, (5) meaning of BMI, (6) meaning of health information technology tools, (7) challenges, (8) overcoming challenges, (9) future and hopes, and (10) meaning of “2030 Saudi vision.” Early in their careers, participants experienced limited opportunities and misperceptions in understanding what the field of informatics represents. Participants did not feel that gender was an issue, despite what feminist theory would have predicted.

Conclusions

Recognizing the lived experiences of women in the field of BMI contributes to our collective understanding of how these experiences may enhance our knowledge of the field.

Keywords: biomedical informatics, health information technology, social sciences, social change, feminism

INTRODUCTION

Despite the golden era of biomedical informatics (BMI),1 an interdisciplinary scientific field that ranges from molecules to persons and populations2 and where professionals serve as the bridge between technology and health professions,3 women are still underrepresented.4 The underrepresentation of women has driven professional scientific organizations, such as the American Medical Informatics Association and the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, to establish women working groups to support women career advancements.5,6

Researchers are also exploring women’s roles in understanding medicine,7 describing young women student experiences in science and technology,8 examining the role of women in medical education,9 and investigating the careers and unique lived experiences of women in the field.10 Within the area of management and leadership, some studies have explored the specific process of selecting women leaders, their leadership style, and performance,11 while other studies examined the roles of women managers across countries.11–13

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), a country that has experienced major social changes within the last 2 years, is pushing forward with its progressive 2030 national vision plan.14 The plan is composed of 13 vision Realization Programs,15 1 of which is the National Transformation Program which focuses on increasing labor market accessibility and attractiveness for women and transforming healthcare. The overarching goals for increasing access to the labor market involves raising the percentage of women’s participation in the labor force (a rate currently at 20.0% as of the fourth quarter of 2019),16 and increasing women’s share in managerial positions through promoting an overall supportive working environment.17

In line with the healthcare transformation initiative, the Saudi Ministry of Health, 1 of the main stakeholders leading the transformation initiative, launched a plan aimed at creating an e-health digitized workplace.18 The plan outlines a future healthcare governance framework based on 7 pillars including investment in healthcare professionals, utilizing efficient health information technology (HIT) systems to improve patient care, and developing HIT policies and research planning.19

With these national plans set up, enormous pressure was placed on BMI professionals to take part in and enable the implementation of these plans on a large scale. The BMI discipline was still relatively recent; established in the Kingdom 15 years prior with the launch of the first advanced Master’s degree program in health informatics, which produced 16 women graduates.20 To assess the readiness of Saudi educational institutions to produce graduates of health informatics prepared to contribute to the e-health digitalized workplace, a recent study highlighted major gaps in programs that offered health informatics degrees, with most being bachelor degree programs focusing on medical coding.21 This in turn posed a challenge for women professionals who wanted to pursue an undergraduate or advanced degree in BMI. Prospective women students would either have to compete for a government scholarship or take on significant expense to self-fund their education. Additionally, many women had to contend with the constraints of the male guardianship system, a legal dictate—which became obsolete in 2019—that mandated women could only travel for study or work with the permission or escort of their closest male relative. For those fortunate enough to secure a place at a Saudi BMI program, there were other challenges. Arabic-speaking students were expected to master the English language during the first years of their undergraduate and graduate programs, as courses were taught exclusively in English. As women informaticians graduated and joined the workforce, it became evident that advanced degrees were not the only requirement for success; sophisticated knowledge, unique skills, long experience, and English proficiency, as well as social support and personal resilience were necessary to advance their careers and become managers in the field of BMI.

In recent years, researchers have focused efforts on studying the challenges facing Saudi women professionals, but very few have explored the realities of women managers.22,23 In an effort to shed light on the experiences of women managers in BMI and gain a deeper understanding of the unique professional dynamics underlying the discipline, our analysis will utilize feminist theoretical frameworks, including standpoint theory. There are few terms that incite as much passion and disagreement as “feminism”. Widely understood as a political movement linked to American and European efforts in the latter half of the 20th century to further women’s rights,24 its utilization in the Saudi context by Saudi authors might appear, at first glance, to be misplaced. However, this research’s principal commitment to strengthen, empower, and further women’s work demonstrates the timeless and universal nature of the feminist project. Any solutions aimed at understanding and overcoming these challenges must first acknowledge the distinct role of gender.

Standpoint theory supports the notion of a unique, socially situated perspective where the situated knowledge of those who are disadvantaged reveals the fundamental irregularities that drive inequality in a way that the knowledge of those who are privileged cannot.25 Standpoint theory addresses the significance of social location to knowledge, its scope, the aspects that facilitate it, its justifications, types, modes of access, and its relationships to other perspectives.25 Marginalized standpoints, therefore, offer a unique perspective that is inaccessible to those who are located externally to these positions and present new insights and understandings into power imbalances and their subsequent oppressive practices. These standpoints can be a locus for more objective and transforming views and should become starting points for dialogue and change.26 By giving voice to the standpoints of women in BMI, this study recognizes their experiences as women in a male-dominated field as valuable epistemological tools.

Women’s experiences as professionals within a masculine discipline ultimately grants them an exclusive epistemic authority. Not only does their situatedness allow them access to a specific and privileged type of knowledge, but it also affords them credibility as speakers and as informaticians.27 It is this knowledge and experience that is fundamental to any effort aimed at supporting and furthering women’s leadership in BMI.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of our qualitative study is to explore how social change driven by the country’s 2030 vision, has affected women in BMI management positions in KSA. Our aim is to understand the role of women in the transformation of healthcare within the context of HIT by describing their lived experiences as managers, exploring the meaning of HIT tools, and identifying challenges that may hinder the advancement of the BMI field.

METHODS

We searched for women managers in the field of BMI to participate in our study through a snowballing technique,28 and we sought to identify a purposeful sample of women by using LinkedIn, an online professional network.29 We conducted semistructured telephone interviews with our participants to understand their lived experiences, how they perceive HIT tools, identify challenges that may hinder the advancement of the field, and explore the future of the field from their perspectives. We utilized feminist standpoint theory to develop the framework for the interview questions and as a lens for the analysis and interpretation of results.

LinkedIn search

Results retrieved from the LinkedIn search engine are based on 4 main factors. The first is the member’s membership level (free account vs. premium subscription).30 The second relates to the member’s network and degree of connection: 1st-degree connections (professionals directly connected to the member through an acceptance of an invitation to connect); 2nd-degree connections (professionals connected to the member’s 1st-degree connections); and 3rd-degree connections (professionals connected to the member’s 2nd-degree connections).31 The third factor relates to how LinkedIn displays search results by default, which is based on search relevance through applying proprietary search algorithms to rank and order the results of a search query. While a specific search query returns the same results for everyone, the order of the retrieved results is determined by specific factors, including a member’s network and level of connections.32 The last factor is based on LinkedIn’s search limitations. While the number of profiles that match a keyword search query may be in the thousands, LinkedIn limits the number of profiles that are displayed to 1000.33 This limitation is partly due to LinkedIn’s unique proprietary search algorithms and suggests that the likelihood of finding relevant profiles matching a particular search query decreases as the number of profiles increases.

Search strategy

We used the paid premium membership account of researcher RD to increase the professional profiles retrieved up to 3rd degree connections. We searched for people within LinkedIn using the search term “informatics” and added the following 2 filters: location “Saudi Arabia,” and “up to 3rd+” connections. Searches were conducted on February 4, 2020. Although the results indicated a total number of 2726 profiles, only the first 1000 profiles were screened, per LinkedIn’s search limitations.

Profiles of women informaticians working in a BMI management position (managers, directors, executive directors) in the following organizational settings: academia, healthcare industry, hospitals, research, and government healthcare institutions were included in this study. Exclusion criteria included profiles of men professionals, women not in the BMI field, and women not in a BMI management position. Profiles that were related to group networks or organizations were also excluded.

Selection and recruitment

Two researchers (RD and JA) conducted the screening by reviewing professionals’ names and profile pictures for inclusion based on gender. Full profile screening (job positions, education background, and work experience) followed name and picture screening, again with the 2 screeners determining inclusion. The final review resulted in identifying 18 women as potential participants in our sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search and screening strategy.

To recruit the 18 women, we developed a short online survey tool consisting of structured questions designed to introduce the purpose and method of our study, obtain informed consent, schedule an interview time, and collect demographics and work experience data. We sent out an invitation to participate with a link to the survey through the LinkedIn messaging feature, and/or a text message to the potential participants’ cell phones. The IRB at the College of Medicine, King Saud University reviewed and approved this study.

Data collection

We used 2 data collection methods: (1) an online survey tool to collect demographic and work experience data—the same tool used for recruitment, and (2) an interview guide (Supplementary Material Appendix 1). In developing the interview guide, we followed the framework developed by Magnanimity et al.34 We designed the semistructured questions based on feminist standpoint theory,25 extensive research on the topic, experience of the research team, and consultation with others experienced in the area of social change and feminist theory. The questions were designed to gain insight into the lived experiences of women in BMI management positions and to identify challenges to their advancement in the field. We also examined their perceptions of the meaning of Saudi Arabia’s 2030 vision and how they viewed the future of BMI in the country. We internally pilot-tested the interview guide and made necessary changes to come up with the final interview guide.

One researcher trained in qualitative research (RD) conducted the interviews. We obtained verbal consent from participants to audio-record the interview, use anonymous quotations, and conduct the interview in English for ease of transcription (giving the participants the option to speak Arabic anytime they preferred). To enhance reliability, one member of the research team (SA) transcribed verbatim all the audio recordings, and RD and JA compared the audio files to transcriptions.35

Data analysis

We summarized responses to structured questions from the online survey using descriptive statistics and analyzed responses to semistructured questions from the interview using thematic content analysis.36 We used the qualitative software program Dedoose37 for coding and analysis of the transcripts. Initially, 3 researchers (RD, JA, and SB) read through all transcripts, then randomly selected 2 transcripts to develop the coding schema. Researchers JA and SB then coded 2 additional transcripts applying the coding schema. When differences occurred, the third researcher (RD) reviewed this coding to reach consensus and agreement before applying the coding schema on the remaining transcripts. The remaining transcripts were then coded by RD, JA, and SB together to reach 100% agreement and consensus. From coding, we identified emergent themes describing the lived experiences of women managers in BMI. To gain a deeper understanding of our findings, RM, a feminist bioethicist, further analyzed the data by utilizing feminist theoretical frameworks in the context of BMI.

RESULTS

A total of 227 LinkedIn profiles belonged to professionals that worked in BMI; 64 (28.2%) were women and 163 (71.8%) were men. Out of those profiles, only 81 professionals were in a managerial position; 18 (22.2%) were women and 63 (77.8%) were men (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screened LinkedIn profiles based on gender, field, and position

| Total Sample | n = 1000 |

n = 227 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informatician |

Manageriala |

|||

| Gender | Yes | no | yes | No |

| Man | 163 (71.8%) | 582 (75.3%) | 63 (77.8%) | 100 (68.5%) |

| Woman | 64 (28.2%) | 191 (24.7%) | 18 (22.2%) | 46 (31.5%) |

| Total | 227 | 773 | 81 | 146 |

Informaticians that hold a managerial position.

Participant description

Of the 18 women managers contacted, 9 women filled out the survey; 2 declined to participate, and 7 agreed to be participants. The women included in our study represent different organizational settings: academia, industry, hospitals, research centers, and government healthcare institutions within KSA. The participants were between the ages of 35 and 50, came into the BMI field from a clinical or computer-science background, had an advanced degree in the area of BMI, and had 5–10 or more years of experience in BMI and management.

Participant career specialty and BMI-related work

Table 2 describes participant responses to specific career questions during the interview. One participant (P1) struggled with giving a specific title for her role. Two participants (P2 and P5) indicated that their current job was their dream job. Two of the participants (P1 and P4) thought they were not paid fairly for their role, while 1 participant (P7) indicated that she didn’t know how to answer the question due to the nonexistence of salary scales to compare against.

Table 2.

Participant career characteristics

| ID. | Area of specialty; “What is the title that you feel best describes you?”; “What would your dream job look like?”; experience in BMI; experience in specific BMI projects; “Do you feel you’re being paid fairly?” |

|---|---|

| P1 | clinical informatics; “… well this is a hard question, very tough 1…”; “… I wish I was given some authority to do my job in the way I see perfect…”; HIT implementation, building infrastructure, research; application development, EHR implementation, research; no |

| P2 | health informatics; “… [specific educational degree]…”; “… honestly, I love what I’m doing now. So, it’s a great opportunity to be a faculty…”; HIT implementation, building infrastructure; educational, research, machine learning for heart surgery, EHR challenges reported by physicians; yes |

| P3 | healthcare management; “… a change agent…”; “… I would love to be a consultant…”; HIT implementation, building infrastructure; EHR implementation; yes |

| P4 | health informatics; “… I’m a health informatician…”; “… preaching, reaching out to people who are afraid of change…”; HIT implementation, building infrastructure; digitization, innovation, transformation, change management, EHR; no |

| P5 | medical informatics; “… [specific job title]…”; “… I accomplished all my goals, thankfully, and I want to continue on the same level…”; HIT implementation, building infrastructure; IT, HIT implementation; yes |

| P6 | health informatics; “… a leading Saudi female in the field of health informatics…”; “… I would like to be in a position where I can make change a, positive change…”; HIT implementation, teaching, research; implementation of a new hardware infrastructure; Clinical application system, data center; yes |

| P7 | information systems; “… for me, maybe, digital transformation, which is regarding technology digitalization, and understanding user needs, developing and delivering it…”; “… my dream job is to be a digital director or an executive director…”; HIT implementation; development and implementation of HIS; don’t know |

Lived experiences of 7 women managers in the field of BMI

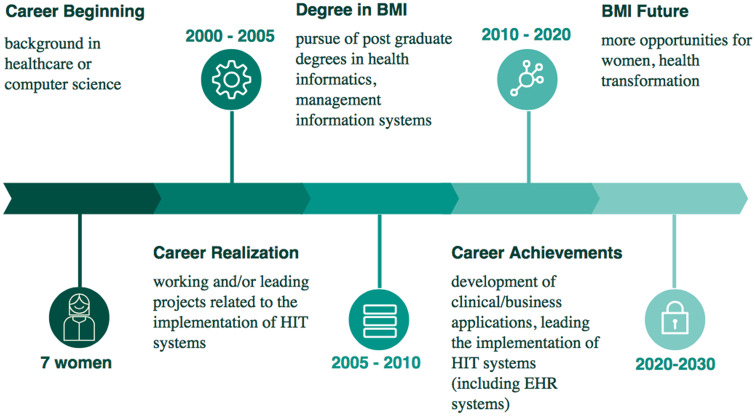

Our focus on describing the lived experiences of women managers in the field of BMI uncovered a similar, shared career timeline. All of the participants came from a background of computer science or healthcare, experienced a phase of realization during their early working careers, pursued an educational degree after working in the field, achieved major accomplishments within their respective organizations and on a national level, and experienced the country’s social transformation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lived experiences of women managers in BMI: timeline.

Furthermore, from the interview data we derived 10 themes: (1) career beginning, (2) opportunities given, (3) career achievements, (4) gender-based experiences, (5) meaning of BMI, (6) meaning of HIT tools, (7) challenges, (8) overcoming challenges, (9) future and hopes, and (10) meaning of “2030 Saudi vision,” grouped within 4 areas.

Career experiences

The first 2 areas, (1) lived career experiences and (2) meaning of BMI and HIT tools included 5 themes. Data analyzed to derive the 5 themes were of a narrative nature, where each participant was describing her career in a story-telling method (Table 3).

Table 3.

Career experiences

| No. | Subtheme | Quotes from participants | count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lived Career Experiences | |||

| Theme 1. Career Beginning | 18 | ||

| 1.1 | Unplanned career in BMI |

|

7 |

| 1.2 | Pioneer in area of specialty/work |

|

7 |

| 1.4 | Early interest in programming |

|

4 |

| Theme 2. Opportunities Given | 7 | ||

| 2.1 | Graduate education and/or training |

|

4 |

| 2.2 | Ability to advance in career and obtain a graduate degree at the same time |

|

2 |

| 2.3 | Career mentorship and support |

|

1 |

| Theme 3. Career Achievements | 14 | ||

| 3.1 | Development of a clinical/business application |

|

6 |

| 3.2 | Implementation of HIT |

|

6 |

| 3.3 | Connecting the bridge between hospitals and educational programs |

|

2 |

| Theme 4. Gender Based Experiences | 8 | ||

| 4.1 | Limited opportunities and challenges for women- an issue from the past |

|

8 |

| Meaning of BMI and HIT Tools | |||

| Theme 5. Meaning of Biomedical Informatics | 23 | ||

| 5.1 | Functions, skills and knowledge of biomedical informatics vs computer science |

|

12 |

| 5.2 | Business analysis in implementing BMI or (IT) tools |

|

6 |

| 5.3 | Bridging the gap between healthcare and IT |

|

5 |

| Theme 6. Meaning of Health Information Technology Tools | 15 | ||

| 6.1 | HIT systems |

|

6 |

| 6.2 | Tools developed to meet the needs of consumers, including patients |

|

5 |

| 6.3 | Technical term linked to computer science and engineering |

|

3 |

| 6.4 | BMI as a whole discipline |

|

1 |

Theme 1: career beginning

During the early beginnings of all the participants’ careers in BMI, they described their involvement in pioneer work related to the development of HIT plans and structures, implementation of HIT systems, educational efforts to distinguish their profession from computer science, and finding themselves sometimes confused about what the BMI field was. One participant specifically expressed an interest in programming during her high school years, only to find out later when obtaining her degree in BMI that it was not purely programming. “…I was thinking that Informatics would be more to teach me or to strengthen my skills in programming. I was surprised that the first-year unit actually was about planning; it was a shock for me at that time.”

Theme 2: opportunities given

Participants continued to describe the opportunities that were available to them to advance in their career. These opportunities were mainly postgraduate education and training. One participant specifically mentioned the importance of mentorship during her early career “… I still have this favor…” indicating the effect of early mentorship as long-lasting and transformative.

Theme 3: career achievements

Nearly all participants described their involvement in implementing a clinical or business IT system, either leading the project or being part of its implementation. One participant found joy in recalling her achievement “… okay what makes me happy, … I was leading the implementation of the HI system…” expressing the importance of becoming a leader during her career.

Theme 4: gender-based experiences

Our participants did not observe gender’s role in their unique lived experiences. Participants expressed discomfort with the idea that their gender may have delayed their progress. One participant referred to the question on gender as a “… tricky question…” indicating her unease, and responded: “I believe it’s an individual thing, maybe men have a better understanding of what they want and how to approach it, but again I would go back to that it’s an individual thing, how you build your career, it’s very much individualized.” For this participant, gender did not play as much a role in career advancement as did individual hard work and achievement.

Even though our participants may not have identified gender-based challenges, some of their experiences might suggest otherwise. Several spoke about being passed over for others with less experience. Two participants shared their disappointment at being pressured to study abroad for several years “… of course I am not going to leave my job and quit working and go to the states or the UK to pursue my education and have a gap in my professional career…” indicating the difficult choice many woman informaticians face early in their careers.

Theme 5: meaning of BMI

Several BMI definitions emerged from participants. Some participants defined it as an interdisciplinary field involving several functions, skills, and knowledge. Participants clearly distinguished BMI from computer science, with the latter focused more on programming and developing technology systems. Participants also indicated that BMI is a transformative discipline that focuses on solving informatics-related problems and issues in different healthcare settings “.transformation of the healthcare from let’s say, paper or manual practice into a new era of technology, so these kinds of automations are not just simple automations, usually it’s transformation.” Some participants defined the field as business analysis manifested in implementing BMI or information technology (IT) tools including understanding business needs and requirements.

Theme 6: meaning of HIT tools

Most of the participants indicated that HIT tools are similar to HIT systems such as radiology systems, laboratory systems, hospital information systems such as electronic health records (EHRs) that contribute to the patient’s journey. Other participants defined HIT tools as tools that are developed to meet consumer needs. One participant expressed her dislike with the term “HIT tools” stating “… don’t like it [the term HIT tools] it brings me back to technology base training in technology you know, which goes back to computer science, or engineering, or computer information systems.” While 1 participant saw HIT tools as BMI as a discipline that covers change management, and user acceptance and awareness.

Challenges faced and the future of BMI

We derived 4 themes under the third and fourth areas; (1) challenges and overcoming challenges, and (2) future of BMI in KSA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Challenges faced and the future of BMI

| No. | Sub-theme | Quotes from participants | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges and Overcoming Challenges | |||

| Theme 7. Challenges | 73 | ||

| 7.1 | Challenges in the advancement of BMI |

|

33 |

| 7.2 | Personal challenges during career including lack of authority and career growth |

|

22 |

| 7.3 | Confusion related to the field of BMI by self of others |

|

14 |

| 7.4 | Past challenges based on gender |

|

4 |

| Theme 8. Overcome Challenges | 18 | ||

| 8.1 | Self confidence in personal knowledge and skills |

|

5 |

| 8.2 | Pursue an educational degree and specialized training |

|

5 |

| 8.3 | Educate others about what the BMI field is |

|

4 |

| 8.4 | Change management- functioning as a bridge between healthcare providers and IT |

|

4 |

| Future of BMI in KSA | |||

| Theme 9. Future and Hopes | 33 | ||

| 9.1 | hopes for the future of BMI field |

|

13 |

| 9.2 | future HIT projects to focus on |

|

12 |

| 9.3 | personal hopes |

|

8 |

| Theme 10. Meaning of 2030 Saudi Vision | 20 | ||

| 10.1 | Health transformation |

|

11 |

| 10.2 | New opportunities for women in BMI and other sectors |

|

4 |

| 10.3 | Development of new HIT projects |

|

3 |

| 10.4 | Privatization of hospitals |

|

2 |

We found some of the participants reluctant to acknowledge personal challenges in their careers. Challenges identified by our participants were either seen as opportunities “… You talk about challenges, but I see them as opportunities…”, or dismissed as an issue of the past “… there’s more Saudi females in every field, and in organizations, they are holding more senior positions, not like before especially in the IT…”.

Theme 7. Challenges

Most challenges described by participants were related to the advancement of the BMI field shown in Table 5. (Supplementary Material Appendix 2). The top issues mentioned were related to data governance and standardization, implementation of EHRs, policies that govern the education and classification of BMI as a profession among other health professions, and lack of recognition. Other participants described personal challenges by struggling with getting the support, acknowledgment, and authority they needed to do their jobs. “I cannot say I have been given full access, control, and power over things…”.

Theme 8. Overcoming challenges

Participants spoke about overcoming challenges by building local human resource capacity “.we need to build up our local cadre, so less reliance on foreign technology, less reliance on expats, and foreigners, and try to train our local cadre, I think that would be the main area, the focus.”, recognizing non- traditional methods of educational degrees “.first of all if they don't recognize online education then many people will not pursue their studies, because people usually go to such specialty after joining a job.”, pursuing formal education and training in BMI, engaging in education activities to increase field recognition, and acting as change agents.

Theme 9. Future and hopes

Participants highlighted the need to invest in several areas for the future of the field, including data analytics, artificial intelligence, disease registries, and precision and prediction medicine. Participants also indicated that future success is dependent on the availability of reliable, high quality, and accurate data. “… we are not really utilizing data effectively and efficiently now in the hospital, at least where I worked.” Participants discussed several directions to focus on for the future of HIT projects, including blockchain technology, development of an innovation lab for prevention of diseases, standardization and interoperability, prediction and treatment of cancer and chronic diseases, standardization of care, and telehealth.

Theme 10. Meaning of the 2030 vision

To all the participants, the Saudi 2030 vision meant health transformation and women’s empowerment. Participants mentioned the vision during conversations about their career achievements, gender-based challenges, and future HIT systems. Health transformation was also connected to technology and digitized healthcare on a national level “… the Ministry of Health vision is to digitalize healthcare to have 75% of the population’s electronic health record digitized by the year 2030, so we should be there or around there at this time.” Participants saw the country’s vision as a gateway which opened new opportunities for women in BMI and other sectors. For some participants, the future meant the development of new HIT projects. Finally, privatization of hospitals was believed to open new opportunities for informaticians, in general, and for women in particular.

DISCUSSION

The particular challenges faced by Saudi women in the workforce have gained much warranted attention by researchers in recent years; very few scholarly works, however, have explored the realities of women managers.22 To our knowledge, no work has examined the experiences of women managers in BMI. It was our contention, at the outset of this research, that gender affects women’s experiences in the workforce. We found that gender did play a significant role, however, not in the manner we had predicted.

The participants in our study are accomplished professionals fronting the continued development of a growing discipline. Collectively, participants’ pioneering work transformed BMI in significant ways including conducting research, developing HIT systems and applications, implementing EHR systems, establishing educational and training departments, and setting both institutional and national policies. In light of ample evidence suggesting that women face various struggles in the workplace,13,38,39 this research began as an effort to gain a deeper understanding of the individual and professional dynamics influencing the experiences of these pioneering women.

During the inception and subsequent design of this study, we utilized feminist standpoint theory as an analytic framework, as we understand gender to be an important social and moral standpoint.25 We posited that participants’ positions as women in a male-dominated field shaped their experiences. We found, however, that participants were hesitant to identify gender-based challenges in their own careers. Any reported challenges were either normalized as part of the work, disguised as something else, or dismissed as past occurrences. The reluctance to identify gender-related challenges is not unique; several studies have suggested that denial of issues of gender might be a coping mechanism.40 In male-dominated disciplines, women’s positions are often precarious,38 and women may choose not to jeopardize these positions by calling attention to themselves.41

Feminist scholars have argued that certain social rules—both formal and informal—systematically advantage some groups over others, resulting in a “structural injustice.”42 Structural injustices sustain inequalities in the distribution of resources, positions, and opportunities.43 This is seen in the experiences of women informaticians who were forced to make the difficult decision of moving abroad within the constraints of the guardianship system while their male counterparts were not. As structural injustices persist, they distort the beliefs of those who operate within them, normalizing inequalities.43 Feminist authors have further argued that social injustices can be internalized, hidden from one’s conscious and obscured by the contradictions of daily life.44–46 Women who are accustomed to discriminatory structures may not readily recognize the manner in which these forces influence their lives. Without this understanding, it becomes difficult to overcome systems of gender discrimination.

The inability to identify structural injustices negatively impacts the epistemic authority of women and their subsequent power to correct these injustices, resulting in further “epistemic injustice.”27 Absent the collective interpretive resources that enable women to recognize, articulate, and validate their social experiences, women may be unable to make sense of their lived realities.27 When some of our participants were probed to express more about gender-based challenges, they were clear in stating that gender discrimination was a thing of the past. They associated the nonexistence of gender discrimination with the country’s transformative and tangible social changes. For our participants, the country’s 2030 vision meant better opportunities and empowerment for women.

Our initial search to identify participants further revealed the significance of gender as a standpoint. LinkedIn search results yielded 18 potential participants—all women managers with advanced degrees, who were invited to take part in our study. Although we did not exclusively target participants with advanced degrees, it was evident from our review of profiles that the women who declined to be interviewed were also accomplished professionals. Based on our knowledge of the field and its challenges, women who declined to participate may have had differing experiences and opinions of gender’s role in BMI, which in turn may have kept them from participating.

Research indicates that individuals working in organized structures or within established fields often feel pressure to conform and comply with institutional norms, rather than challenge them, in order to maintain their employment, their inclusion, or their status.47 Reported reasons for remaining silent include lack of support, wanting to avoid negative labels, fear of damaging work relationships, and not believing that speaking up will change anything.48 The women who declined to take part in our research may have felt that participation may pose a risk to their careers.47

Ultimately, our analytical framework did not identify gender-based challenges in the way we had anticipated. Still, standpoint theory proved a useful lens for this study, as it revealed privileged knowledge regarding how women managers in BMI perceive their positions in a male-dominated field and a private account of their lived experiences, challenges, and expectations.

The limited number of our participants may reflect the true underrepresentation of Saudi women in BMI management positions. Our participants started their careers following a passion for science and technology. During their early careers, these women experienced misperceptions from others and/or from within themselves on what the BMI field represents. They were unaware that the roles they were in were informaticians’ roles. Some have expressed their struggle to situate themselves within the field and to be recognized as informaticians as reflected in policies that set classification and salary scales for different professions. As a result, they pursued postgraduate degrees in BMI and became ambassadors of the field, highlighting the first contributions—approximately early 2000s—of Saudi women in BMI.

As Saudi Arabia pushes forwards its transformative 2030 vision,14 the empowerment of women in all professional sectors has taken on a newfound importance. In order to do so, gender-based discrimination must be acknowledged and dealt with. As several studies have shown, denial of gender inequality is 1 of the most significant obstacles to social change.40 Gender, we maintain, remains an essential standpoint in our study, even if our participants had difficulty identifying its role. Recognizing and understanding the experiences of women—including those which have not been articulated—is essential to making sure we do not ignore the incredible progress Saudi women have made in the workforce.

Based on our findings, and in order to reach more diverse groups of women, follow-up studies will explore the lived experiences of women in BMI throughout different stages of their careers. Our aim is to gain a broader understanding of their lived experiences to encourage more women to enter the field. It is crucial to work with educational institutions as well as employers to ensure that more BMI graduate programs are established within the country and more career opportunities are available to increase participation of women in the field of BMI. Equally important is developing outreach programs that feature women role models to attract women to participate in BMI education and research and ensure their continued participation in different organizations at equal ratios with their men colleagues.

Limitations

Our sample was dependent on using the snowball technique based on participants’ connections with the research team through LinkedIn. Due to the absence of a specialized database of BMI professionals in Saudi Arabia, LinkedIn was used in an effort to recruit as many Saudi BMI women managers as possible. Using this method, we may have missed women informatician managers that were not within the research team’s level of connections and/or did not have an account on LinkedIn, which in turn contributed to the small sample size limiting the generalizability of our findings. We chose to use telephone interviews to reach participants in different cities within the country (for better representation), which may have limited our ability to obtain contextual information. Participants who declined to be part of the study may have had different experiences and views from our study population.

CONCLUSION

Social changes have an impact on how women experience career growth, identify past challenges, and on personal perceptions regarding the advancement of healthcare technologies and the field of BMI. Findings showed that our study participants did not describe issues of gender inequality and did not indicate gender as an issue that shaped their career. Studies like this, aimed at recognizing and validating the lived experiences of women in science and technology, contribute to our collective understanding of how these experiences may enhance our knowledge of these fields in the context of healthcare technological advancements and work imbalances.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RD was responsible for the study design. RD, JA, and SB created the semistructured interview guide. RD conducted the interviews. SA transcribed the interview recordings. RD, JA, and SB coded the data. RD, JA, SB, and RM analyzed and interpreted the data. RM contributed to the deeper analysis from a feminist perspective. RD, JA, SB, RM, and SA contributed to drafting, writing, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors gave input to the final version and provided final approval to be published.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank all the bright, remarkable, and pioneering women, who shared their exceptional stories to be part of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moore JH, Holmes JH.. The golden era of biomedical informatics has begun. BioData Min 2016; 9 (1). doi: 10.1186/s13040-016-0092-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kulikowski CA, Shortliffe EH, Currie LM, et al. AMIA board white paper: definition of biomedical informatics and specification of core competencies for graduate education in the discipline. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19 (6): 931–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hersh W. A stimulus to define informatics and health information technology. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2009; 9 (1): 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonham KS, Stefan MI.. Women are underrepresented in computational biology: an analysis of the scholarly literature in biology, computer science, and computational biology. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13 (10): e1005134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AMIA. Women in AMIA Initiative. https://www.amia.org/women-amia-initiative Accessed February 27, 2020

- 6.HIMSS. Women in Health IT Community. https://www.himss.org/membership-participation/women-health-it Accessed February 27, 2020

- 7. Al-Amoudi SM. Health empowerment and health rights in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2017; 38 (8): 785–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makarova E, Aeschlimann B, Herzog W.. Why is the pipeline leaking? Experiences of young women in STEM vocational education and training and their adjustment strategies. Empir Res Vocat Educ Train 2016; 8 (1): 1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40461-016-0027-y [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alwazzan L, Rees CE.. Women in medical education: views and experiences from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Med Educ 2016; 50 (8): 852–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amon MJ. Looking through the glass ceiling: a qualitative study of STEM women’s career narratives. Front Psychol 2017; 8: 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gipson AN, Pfaff DL, Mendelsohn DB, Catenacci LT, Burke WW.. Women and leadership. J Appl Behav Sci 2017; 53 (1): 32–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burke RJ. Managerial women’s career experiences, satisfaction and well-being: a five country study. Cross Cult Manag 2001; 8 (3/4): 117–33. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davidson MJ, Burke RJ.. Women in management: current research issues volume II In: Women in Management: Current Research Issues Volume II. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saudi Vision 2030. https://vision2030.gov.sa/en Accessed February 28, 2020

- 15.Programs | Saudi Vision 2030. https://vision2030.gov.sa/en/programs Accessed April 22, 2020

- 16.General Authority for Statistics. Labor Market Fourth Quarter 2019. http://www.stats.gov.sa Accessed April 22, 2020

- 17.National Transformation Program; 2018. https://vision2030.gov.sa/sites/default/files/attachments/NTP English Public Document_2810.pdf Accessed April 22, 2020

- 18.Healthcare Transformation Strategy. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/vro/Pages/Health-Transformation-Strategy.aspx Accessed February 28, 2020

- 19.Digital Health Strategy. https://www.moh.gov.sa/Ministry/vro/eHealth/Documents/MoH-Digital-Health-Strategy-Update.pdf Accessed April 21, 2020

- 20. Altuwaijri MM. Supporting the Saudi e-health initiative: the Master of Health Informatics programme at KSAU-HS. East Mediterr Health J 2010; 16 (01): 119–24. CrossRef][10.26719/2010.16.1.119] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noor A. Discovering gaps in Saudi education for digital health transformation. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 2019; 10 (10): 105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Ahmadi H. Challenges facing women leaders in Saudi Arabia. Hum Resour Dev Int 2011; 14 (2): 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al-Asfour A, Tlaiss HA, Khan SA, Rajasekar J.. Saudi women’s work challenges and barriers to career advancement. Career Dev Int 2017; 22 (2): 184–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24. McAfee N. Feminist philosophy In: Zalta EN, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/feminist-philosophy/ Accessed August 12, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anderson E. Feminist epistemology and philosophy of science In: Zalta Edward N., ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; 2017 https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/feminism-epistemology Accessed August 12, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haraway D. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud 1988; 14 (3): 575. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fricker M. Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing; 2007. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001/acprof-9780198237907 Accessed August 12, 2020

- 28. Streeton R, Cooke M, Campbell J.. Researching the researchers: using a snowballing technique. Nurse Res 2004; 12 (1): 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LinkedIn. Log In or Sign Up. https://www.linkedin.com/ Accessed February 27, 2020

- 30.LinkedIn. Free Accounts and Premium Subscriptions | LinkedIn Help. https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/71/linkedin-free-accounts-and-premium-subscriptions? lang=en Accessed April 21, 2020

- 31.LinkedIn. Your Network and Degrees of Connection | LinkedIn Help. https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/110/your-network-and-degrees-of-connection? lang=en Accessed April 19, 2020

- 32.LinkedIn. Search Relevance-People Search | LinkedIn Help. https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/4447/linkedin-search-relevance-people-search? lang=en Accessed April 19, 2020

- 33.LinkedIn. Search Results for Free and Premium Members | LinkedIn Help. https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/129/search-results-for-free-and-premium-members? lang=en Accessed April 19, 2020

- 34. Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M, Kangasniemi M.. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72 (12): 2954–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silverman D. Qualitative Research : Theory, Method and Practice. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3 (2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dedoose Version XXX. Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data; 2018. www.dedoose.com Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 38. Ryan MK, Haslam SA.. The glass cliff: evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. Br J Manag 2005; 16 (2): 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Adler NJ. An international perspective on the barriers to the advancement of women managers. Appl Psychol 1993; 42 (4): 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morrison Z, Bourke M, Kelley C. “ Stop making it such a big issue”: perceptions and experiences of gender inequality by undergraduates at a British University. Womens Stud Int Forum 2005; 28 (2-3): 150–62. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muaygil RA. Beyond sacredness: why Saudi Arabian bioethics must be feminist. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth 2018; 11 (1): 125–43. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haslanger S. Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique; 2012 . https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199892631.001.0001/acprof-9780199892631 Accessed August 12, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jugov T, Ypi L.. Structural injustice, epistemic opacity, and the responsibilities of the oppressed. J Soc Philos 2019; 50 (1): 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mackinnon CA. Feminism, marxism, method, and the state: toward feminist jurisprudence. Signs: J Women Cult Soc 1983; 8: 635–58. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gorelick S. Contradictions of feminist methodology. Gend Soc 1991; 5 (4): 459–77. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrews M. Feminist research with non-feminist and anti-feminist women: meeting the challenge. Fem Psychol 2002; 12 (1): 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J. “ Don’t rock the boat”: nursing students’ experiences of conformity and compliance. Nurse Educ Today 2009; 29 (3): 342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Milliken FJ, Morrison EW, Hewlin PF.. An exploratory study of employee silence: issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. J Manag Stud 2003; 40 (6): 1453–76. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.