Abstract

Objective

With age, older adults experience a greater number of chronic diseases and medical visits, and an increased need to manage their health information. Technological advances in consumer health information technologies (HITs) help patients gather, track, and organize their health information within and outside of clinical settings. However, HITs have not focused on the needs of older adults and their caregivers. The goal of the SOARING (Studying Older Adults and Researching their Information Needs and Goals) Project was to understand older adult personal health information management (PHIM) needs and practices to inform the design of HITs that support older adults.

Materials and Methods

Drawing on the Work System Model, we took an ecological approach to investigate PHIM needs and practices of older adults in different residential settings. We conducted in-depth interviews and surveys with adults 60 years of age and older.

Results

We performed on-site in-person interview sessions with 88 generally healthy older adults in various settings including independent housing, retirement communities, assisted living, and homelessness. Our analysis revealed 5 key PHIM activities that older adults engage in: seeking, tracking, organizing, sharing health information, and emergency planning. We identified 3 major themes influencing older adults’ practice of PHIM: (1) older adults are most concerned with maintaining health and preventing illness, (2) older adults frequently involve others in PHIM activities, and (3) older adults’ approach to PHIM is situational and context-dependent.

Discussion

Older adults’ approaches to PHIM are dynamic and sensitive to changes in health, social networks, personal habits, motivations, and goals.

Conclusions

PHIM tools that meet the needs of older adults should accommodate the dynamic nature of aging and variations in individual, organizational, and social contexts.

Keywords: older adults, personal health information, health information management, aging

BACKGROUND

As adults age, there is often a corresponding increase in medical visits and medications, and thus a greater need to complete paperwork, track conditions, manage medications, make decisions, and plan for the future.1 This process of managing various aspects of personal health information (PHI), which includes organization, integration, and use of information, has been called PHI management (PHIM).2

Advances in health information technologies (HITs), such as assistive living technologies, self-management monitoring systems, patient portals, and health dashboards have helped patients to gather, track, and organize their health information both within and outside of clinical settings.3–5 Some HITs have improved patients’ quality of life, relationship with their doctor,6,7 and capacity to participate in their health care.8,9 However, research has only begun to ascertain the broader impacts of HIT on healthcare quality across diverse populations, including older adults.10,11 Although older adults have generally been slower to adopt new technologies than their younger counterparts, there has been a steady increase in digital technology use among older adults over the last decade.12 Approximately 40% of adults 65 years of age and older use smartphones and social media.10,13 A 2018 national poll found that half of adults 50-80 years of age reported signing up for patient portals.14

Designing HIT solutions for older adults is significant because their healthcare needs often exceed those of their younger counterparts, and their capacity to effectively manage those needs can be compromised by age-related changes.15 With few exceptions, the design of HIT has not focused on meeting the needs of older adults and their caregivers, nor taken into consideration the relevant factors motivating their HIT use.5 Mitzner et al16 argued that technology designed to be useful for older adults needs to take into consideration cognitive function, health literacy, a broad spectrum of abilities, experience with technology, and willingness to engage with digital tools. For older adults, providing initial positive experiences with a given a technology is a strong facilitator to adoption. In addition, efforts need to be in place to promote ongoing engagement and training.16,17

Numerous personal barriers, such as low health literacy and digital literacy, lack of comfort with computers, lack of technology integration into everyday life, and discomfort communicating with providers online may limit the adoption of HIT by older adults.18–23 Broader sociotechnical influences such as available tools and technologies and organizational, physical, and social contexts can pose particular challenges.18,24,25 Better understanding these challenges and barriers could improve the design, usability, and integration of PHIM tools into older adults’ daily life.5,23,26–28

The goal of the University of Washington SOARING (Studying Older Adults and Researching their Information Needs and Goals) Project (soaringstudy.org) was to better understand older adult PHIM to inform the design of effective PHIM tools. We approached the study of older adult PHIM through the Work System Model sociotechnical framework,29 placing the older adult and their PHIM activities in the center of focus, surrounded by influencing factors of tools and technologies, and organizational, social, and physical contexts.18,20,30–33

In this article, we describe one study in the SOARING project that highlights how a mixed methods field study approach can provide insight into the characteristics and PHIM practices among a cohort of older adults living in diverse residential settings in Seattle, Washington. We then discuss older adult PHIM in the context of a methodological lens that includes sociotechnical factors of available technologies, organizational structures, the lived environment,18,24,30 and personal motivators (eg, internal and external factors driving decision making)34 to identify possible HIT solutions to support PHIM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a mixed methods field study in 2 parts. First, we collected qualitative and quantitative data about participants and their PHIM-related activities through on-site sessions involving semi-structured interviews sessions and administration of validated survey instruments. We then conducted a follow-up feedback survey to confirm our findings and explore motivators for PHIM activities.

Participant recruitment

We purposively sampled participants from different living situations (ie, retirement communities, independent living, assisted living, and homelessness). Staff at retirement communities and assisted living facilities shared recruitment information with eligible residents and we posted fliers at community organizations and public spaces frequented by older adults in the Seattle area. All study protocols and materials were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Criteria for participating included: 60 years of age or older, ability to communicate in English, lack of cognitive impairment as judged by a score of 4 or higher on the Six-Item-Screener,35 and residing in the Seattle metropolitan area. Although 65 years of age is often the age used to define older adults, we were also interested in the practices and challenges of individuals who were still in the workforce and who would be 65 years of age by the end of the 5-year project. In-person interview sessions lasted 1.5-2 hours. When possible, interviews took place in the participant’s living space. Alternatively, interviews took place in a common room of the participant’s living facility or at a local community center.

Data collection

Part 1. In-depth interview sessions

In-depth interviews

The interview guide included semi-structured questions focused on general health, social networks, health information received and used, and health information management needs and practices (see Supplementary Appendix A). The topic areas covered were informed by the Work System Model29 and designed to provide data on the individual, tasks, organizations, environment, and tools and technologies that influence the work of PHIM. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. With participant permission, we took photos of artifacts and tools used to manage PHI. We edited photos to remove identifying information.

Validated instruments

We used surveys to collect participant characteristics, including demographics, living situation, and technology usage. We used validated instruments to collect information about participants’ comorbidities,36 social networks,37 decision-making and information-seeking preferences and problem solving style,38 and e-health literacy.39 A summary of topics covered in the quantitative portion of the initial in-depth interviews, as well as the feedback survey, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative focus areas for initial interviews and feedback survey

| In-depth interviews and survey instruments | Feedback survey |

|---|---|

|

|

Part 2. Participant feedback survey

After completing our analysis of the in-depth interviews (∼1 year after initial interviews), we conducted a 49-item feedback survey with participants to confirm whether our identified themes, PHIM activities, approaches, and motivators aligned with their perceptions. We also used the survey to learn more about their motivations for taking particular PHIM approaches and current use of technology for PHIM processes. Additional questions focused on medication management, technology usage, patient portal usage, privacy, and desired HIT functionality (Supplementary Appendix B). The feedback survey was developed based on items from existing instruments; face validity was addressed by review and feedback from experts in gerontology and geriatrics and instrument development. Results were collected using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, Web-based application for data collection and storage.40 We contacted in-depth interview participants who expressed willingness to be contacted for follow-up studies (n = 73). After obtaining consent, we administered the survey in person, using a digital tablet to enter participant responses.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis: In-depth interviews

We analyzed interview transcripts and photos using thematic analysis.41 We reviewed a subset of transcripts for emerging themes to develop an initial codebook. Two researchers (K.P.O. and J.J.) applied the codes to all transcripts, using the qualitative software program Dedoose (version 7.5.9; Dedoose, Manhattan Beach, CA). To ensure coding consistency, researchers double-coded 10% of the transcripts and met weekly to calculate intercoder agreement (final 89.6%), discuss coding discrepancies, and reach consensus prior to further coding. Upon completion of coding, we developed a list of key PHIM activities as themes that emerged. Using affinity diagramming,42 we reviewed coded interviews to identify different approaches to carrying out PHIM activities, categorized and labeled those approaches, and assigned the approaches to participants based on responses. We also reviewed excerpts for each PHIM activity to identify related motivators.

Quantitative analysis: Initial survey

We summarized the demographic data and data from the validated instruments using descriptive statistics. We conducted bivariate analyses between participant characteristics identified through the in-depth interview validated instruments to their approach to a PHIM activity, with the PHIM approach as an outcome variable (treated as a categorical variable) and patient characteristic as covariate. The analysis method depended on the type of the covariate (categorical, ordinal, or continuous). We used Fisher’s exact test for categorical and ordinal characteristics (race or ethnicity, sex, relationship status, living situation, income, retirement status, living alone, Medicare, and technology use) and multinomial regression for analyses for continuous characteristics (age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, Lubben Social Network Scale subscales, Autonomy Preference Index subscales, and eHealth Literacy Scale). Statistical significance of each association was determined by comparing change in deviance between a null model and the model containing the covariate with a chi-square test. We present associations that were statistically significant at the alpha = 0.05 level, but because it is an exploratory analysis, we do not present specific P values.

Feedback survey

We reviewed responses to semi-structured questions from the feedback survey for themes regarding motivators for PHIM activities and their associated approaches.

RESULTS

A diagram summarizing the study design and number of participants is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of study design. PHIM: personal health information management.

Participants: In-depth interview sessions

We recruited 90 participants, and 88 (98%) completed in-depth interview sessions (See Table 2). Participants ranged in age from 60 to 98 years, and were largely women and college educated. Participants were evenly distributed between independent living, retirement living, and assisted living. Two participants described themselves as homeless. On average, participants reported low Charlson Comorbidity Index scores and were not at risk for social isolation (ie, Lubben Social Network Scale = 6 < 12). On average, participants were information seeking but moderate in their preference for involvement in medical decision making (44 on scale from 1 to 100). Participants’ average eHealth literacy score (24.8 ± 9) was lower than reported in studies of older adults recruited online (30.9 ± 6).43

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Demographics | Data (N = 88) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 60-69, y | 23 (26) |

| 70-79, y | 32 (36) |

| 80-89, y | 19 (22) |

| 90-99, y | 14 (16) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 61 (69.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 62 (70.5) |

| Asian | 8 (9.1) |

| Black | 6 (6.8) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 (6.8) |

| Other/refused | 6 (6.8) |

| Education | |

| Some high school or high school diploma | 10 (11.5) |

| Some college | 23 (26.4) |

| College graduate | 28 (32.2) |

| Postgraduate education | 26 (29.9) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.1) |

| Income | |

| Not at all adequate OR can meet necessities only | 15 (17) |

| Can afford some of the things I want but not all I want | 39 (45) |

| Can afford about everything I want | 26 (30) |

| Can afford about everything I want and still have money left over | 7 (8) |

| Relationship status | |

| Divorced/separated | 27 (31) |

| Widowed | 27 (31) |

| Married/partnered | 23 (26) |

| Single, never married or partnered | 11 (12) |

| Retired | 77 (87.5) |

| Lives alone | 61 (69.3) |

| Has Medicare | 79 (89.8) |

| Living situation | |

| Retirement community | 24 (27.3) |

| Independent shared dwelling | 24 (27.3) |

| Independent | 22 (25) |

| Assisted living | 17 (19.3) |

| Homeless | 1 (1.1) |

| Technology use | |

| Has computer access | 78 (88.6) |

| Owns a cell phone | 69 (78.4) |

| Portal use (current) | 27 (31) |

| Validated instruments | |

| Average Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.0 ± 1.3 |

| LSNS friends subscale | 9.2 (3.9) |

| LSNS family subscale | 8.1 (3.5) |

| API decision-making scale (0-100) | 44 (20) |

| API information-seeking scale (0-100) | 84 (12) |

| eHEALS score | 24.8 (9.0) |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

API: Autonomy Preference Index; eHEALS: eHealth Literacy Scale; LSNS: Lubben Social Network Scale

Participants: Feedback survey

We administered the feedback survey with 38 of the 73 original interview session participants who agreed to be recontacted. The age range was 63 to 98 years. The demographic characteristics of those participants were similar to in-depth interview session participants in terms of sex, living situation, race or ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status.

Key PHIM activities of older adults

Our qualitative analysis of interviews revealed 5 PHIM activities described by participants: seeking, tracking, organizing, sharing, and emergency planning (Table 3). Tools used to support these activities included participants’ memories, paper (notepads, calendars, Post-its), pillboxes, medical devices (eg, glucometer), phones, computers, patient portals, and other people. Motivators, identified through responses to in-depth interview questions and further explored in the feedback survey, are described subsequently.

Table 3.

Personal health information management activities

| Activity | Definition | Approach | Distribution (n = 88) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeking | Type of engagement with obtaining health-related information |

|

|

| Tracking | Generating and/or logging of health-related measures |

|

|

| Organizing | Strategy used for handling health-related print materials |

|

|

| Sharing | Including others (family/friends) in communication and management of health-related information |

|

|

| Emergency planning | Preparing and maintaining information in case of a health-related emergency |

|

|

Seeking

Participants exhibited different levels of initiative in seeking health information. Those participants who described taking an active approach to seeking health information searched the internet, and spoke with medically knowledgeable individuals (including physicians and family members with clinical backgrounds) to understand health issues.44 Active seekers rarely relied on a single source, but rather utilized multiple sources.

“I pull it up on the computer… And then I’ll discuss it with a girlfriend… And they’ll tell me what the doctor told them … And then when I go to the doctor I’ll ask them about it.” (P4)

Active seekers tended to be more open to portal use. A high proportion (80%) of the participants classified as active seekers reported accessing their patient portal at least once.

Older adults classified as using a passive approach for collecting health information described themselves doing little intentional seeking of health information. Examples of a passive approach included waiting to obtain desired information at a doctor’s appointment, receiving health information through watching TV, or coming across it while reading a magazine or newspaper. This form of collecting health information was often serendipitous, as in learning something new by chance. Nearly a third of participants fluctuated between passive and active health information seeking, using a combination of approaches rather than relying on one approach.

Tracking

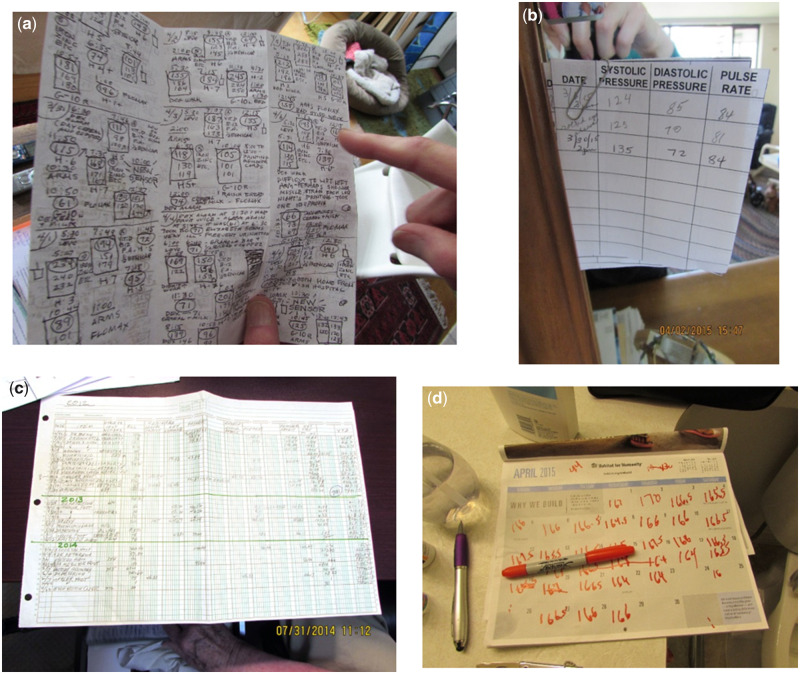

Keeping track of one’s health status or symptoms was an important PHIM activity described by many participants. We defined tracking as generating or logging personal health measures over time. Over half of participants tracked health related information by generating or logging measures (eg, blood sugar, weight) in a notebook or on a computer using their own system (Figures 2A and 2B) or using preexisting forms (eg, from a healthcare facility) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A–D) Images of personal health information tracking. (A) Insulin/glucose/diet log, (B) Daily blood pressure, (C) Medical expenditures, and (D) Daily weight.

Participants also described making notes about how they felt, medications they took, or water consumption. Other participants described using calendars for tracking symptoms or noting questions for health-related appointments (Figure 2D).

“I keep track of every single bill and every single insulin shot that is given.” (P24)

Half of the participants indicated that they tracked consistently, and the other half tracked health information intermittently. Some participants tracked for only short periods, usually for an emerging health issue (eg, higher-than-normal blood pressure), or for intermittent efforts to be healthier (eg, weight, exercise, food intake).

The general motivation for tracking health-related information was the usefulness of the information for oneself (eg, for comparing values over time, understanding the timing of symptoms), sharing information with the healthcare team, or compliance with a providers’ instructions.

These findings were consistent with the feedback survey, in which respondents reported that they were motivated to track specific health conditions (eg, blood sugar for diabetes or weight for obesity). Individuals who did not track often described themselves in good health, and therefore not needing to track health information. For example, participants mentioned that they “had nothing to worry about” or “no need [to record health information].” Additional reasons cited for not tracking were that assisted living facilities tracked needed information on the participants’ behalf, or that the participant had “no interest.”

Organizing

Participants described three organizing approaches that they used for handling health-related print materials such as clinic summaries, medication lists, insurance claims, and health education materials: tossing, filing, and piling (see Figure 3). All participants used some form of paper to organize or curate their health information, including handwritten lists, Post-it notes, and files.

Figure 3.

Images of organizing health information.

Common criteria mentioned for deciding to keep information were credibility, timeliness, and convenience. Most of the participants kept at least some health information, but a small number chose to “toss” nearly all their health-related papers:

“Well I don’t like a lot of paper around. I just study what I need to study and then they go in the garbage or the shredder.” (P50)

Almost half of participants filed health-related information. We defined the file approach as following some organizational criteria, though not necessarily utilizing a physical file folder. Common organizing schemes were chronological or categorical (eg, medical condition, finances/taxes).

The most common motivator mentioned in in-depth interviews for filing information was to have it available “just in case” it may be needed in the future, specifically for financial or tax purposes or for reference about health conditions. Participants who described themselves as being organized were often in the filer category, with some stating that filing was a “habit.” Two participants described failed efforts to adopt an organizational system for filing health-related information that someone else (eg, an adult child) developed.

Some participants described shifting away from keeping print materials as they relied more on patient portals. These participants appreciated the ability to have the information electronically stored, which saved them from having to make decisions about keeping health information.

“I’ve gotten to the point where just about anything I want, I’ll find there [portal].” (P30)

However, some participants expressed concerns about electronic health systems:

“I’m not dumb enough to rely on just the computer. People that say, ‘Oh well, I don’t need a copy because it’s in the computer,’ technology, honey, it breaks down. It eats things. And you can’t find them again.” (P66)

Almost 40% of participants (n = 88) described piling their health-related information. We defined a pile as a collection of generally unorganized information that existed on top of a surface or was even located in a file folder but was not sorted in any systematic way:

“I keep all my health records. I just put them in a box under my desk.” (P25)

Some participants kept their health information piled in the open for accessibility or as a reminder to do some health-related activity (eg, going to a doctor’s appointment). Some would read the information again, and then toss it. These participants were more likely to mention a desire to have information available for general reference, rather than for reference about a particular condition.

The feedback survey confirmed that filers did so in order to have information available in the future and because it was their habit to be organized. Interestingly, many survey respondents mentioned that they adopted their approach to organizing health information (either tossing or keeping it) because they were not sure what else to do with it. The feedback survey also revealed that 84% (n = 34) of participants were consistent in their organizational styles. For example, if they filed their health information, they tended to file financial information and other paperwork.

Sharing

In general, most participants (80%) involved other people in managing health information. The most common approach was to engage in PHIM activities independently while (sometimes reluctantly) sharing with concerned friends and family in response to requests and in preparation for possible future care. The other approach was to engage collaboratively in PHIM activities, sharing information and accepting help as needed. Examples of collaborative PHIM activities included searching for health information, organizing health-related papers, and calendaring and setting up medical appointments. In some cases, the participant managed most health information themselves and only handed off specific tasks to others. Other collaborative teams or partnerships more evenly shared PHIM activities.

Only a small number of participants chose not to involve family or friends in their PHIM related activities (11%); their preference for independence or the desire not be a burden and the desire for privacy were underlying motivations for not sharing.

A small number of participants did not manage their health information at all. Instead, PHIM was conducted on their behalf by through a “proxy.”

“I pretty much give that important kind of stuff like that to my daughter. She keeps track of stuff because she knows I won’t remember.” (P65)

Participants expressed their motivator for having a proxy as needing help, whether that was for medication support, finances, tracking, decision making, scheduling, or communication with the doctor. Two participants explicitly stated cognitive decline as a motivator.

Emergency planning

Two-thirds of participants developed plans for health-related emergencies. They either planned by themselves or others planned for them. Information used for emergency planning came in a variety of formats: emergency contact lists, medication lists, POLST forms,45 and medical condition or allergy lists (Figure 4). The most common reason for emergency planning was to satisfy residential living requirements. Other reasons were ensuring that desires were followed, and encouragement by family members or friends. In the feedback survey, some participants mentioned doctors and attorneys encouraging them to develop and update emergency plans or contacts and living wills.

Figure 4.

Emergency planning management.

Many participants prepared emergency information independently. Participants often placed documents and lists in visible locations, such as on refrigerators or walls. Unfortunately, some participants who had prepared an emergency plan failed to post it or could not remember where it was.

… let’s see, where was the last time I saw that? I saw it not too long ago…I don’t know where it is right now. (P10)

Some participants had emergency information maintained on their behalf. These participants often lived in facilities where staff maintained emergency information for them. Participants in such facilities often had access to physical emergency notification systems such as pull cords, buttons, or wearable devices, which connected them to the individuals who had access to emergency information.

A third of participants did not have emergency planning information. Reasons included not getting around to it, not liking the appearance of emergency materials in one’s home, or a perception that it was unnecessary because of good health:

“I don’t have any of that [emergency planning materials]. I still feel well enough not to need that. I imagine there will come a time when I will need that kind of stuff.” (P59)

Of the 35 respondents on the feedback survey who described how often they updated their emergency information, 31% said that they updated their forms only if something changed, and about 40% said they had updated their information within the past 5 years. About a third of those who had recently updated their information mentioned doing so on a recurring basis, with some receiving reminders from their living facility or healthcare provider. In contrast, 17% said they hadn’t updated their information since they created it, or it had been over 10 years since it was updated.

PHIM themes

Across the described PHIM activities, several contextual themes emerged consistent with the Work System Model framework.29 Some of these themes have been touched on in publications regarding our research5,15,43,46,47 and are summarized here for continuity and completeness: (1) older adults primarily engage in PHIM to maintain a healthy and active life, (2) older adults frequently involve others in key PHIM activities, and (3) older adult approaches to these PHIM activities depend more on context than personal style.

Theme 1: Maintaining a healthy and active life

We began interviews by asking participants to describe their current life goals. The goals most frequently mentioned were to remain healthy and to spend time with family and loved ones. Participants described tasks and goals related to well-being that encompassed physical, emotional, mental, social and spiritual aspects of their lives, indicating hope for a vibrant and active life while aging. Table 4 details the breadth of these goals.

Table 4.

Overall life goal themes

| Theme | Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Pursuit of health | “You want to stay as healthy as you can as long as you can.” (P40) |

| “My goal is just to keep breathing well, you know. Healthy.” (P45) | |

| Live well | “Just to keep going. Keep dancing.” (P48) |

| “I think we'd like to travel some.” (P53) | |

| Continue to learn | “To stay mentally alert which is a worrisome thing.” (P35) |

| To continue satisfying my ongoing curiosity about everything (P36) | |

| Contentment | “to savor all the good stuff in each day” (P36) |

| “My goal for my life is to just live my life contentedly.”(P51) | |

| Time with others | “Well I, I really, I mean, I'm 80, I haven't got no goals now but to love and be loved. And have someone care, and that's about it.” (P46) |

| Think of others | “to make life better for other people, to never be grumpy.”(P32) |

| Spiritual focus | “I’d say to honor the Lord in all that I do.” (P19) |

| Readiness for death | “I appreciate life but I'm not afraid to die. I'm sort of looking forward to it. Every now and then I think oh, yeah, it'd be nice to be gone.” (P32) |

For the most part, participants’ life goals did not explicitly focus on PHIM. This connection only occurred when we asked participants to describe what activities they engaged in to meet their wellness goals and manage health information. Our interview findings confirmed findings from preliminary focus groups performed early in the SOARING study, namely that maintaining health and wellness was a key motivating factor for tracking, seeking, organizing, and planning health information.46

Theme 2: Older adults often involve others in key PHIM activities

In carrying out PHIM activities, such as seeking health information or emergency planning, older adults often involved other individuals, including family and friends. The extent and type of involvement differed between individuals, depending on their need or desire for help and their social network. In many ways PHIM could be viewed in a social context. In fact, individual approaches to PHIM activities were often characterized by the extent to which the older adults involved others in PHIM activities such as seeking information and emergency planning.47,48

Theme 3: Older adult PHIM is a situationally based process

The 5 PHIM activities are embedded in older adults’ everyday lives, and thus were influenced by characteristics of the older adult, as well as level of involvement of others, living situation, digital literacy, and use of available tools and technologies. These influences were reflected in interviews and the data collected from the validated survey instruments and were confirmed in the feedback survey.

Age was associated with PHIM attributes of emergency planning and organizing health related print materials. Compared with participants in the 60- to 69-years-old range, participants 80 years of age or older were more likely to fall into the plan by others category (45.2% vs 8.7%) and the filing category (56.9% vs 26.1%). Participants within the lowest tercile of perceived digital health literacy were more likely than participants in the highest tercile to fall into the plan-by-others category (55.6% vs 8.0%), into the proxy sharing category (13.8% vs 4.0%), and into the passive seeking category (41.4% vs 0.0%). In other words, those with lower health literacy were more likely to let others plan for them and less likely to actively seek out information.

Technology use

Strong associations were observed for computer usage and PHIM activities such as seeking, emergency planning, and tracking. Participants who actively used computers were more likely to be active seekers (70.8% vs 15.6%), less likely to fall into the plan-by-others category (16.7% vs 51.7%), and more likely to consistently track information (45.8% vs 12.5%).

Associations were also noted between cell phone usage and seeking, sharing, and organizing. Participants who used cellphones for more activities were more likely to be active seekers (62.5% vs 44.2%), to fall into the independent but shares category (54.2% vs 25.0%), and to organize information by tossing (45.8% vs 30.8%).

Finally, our results indicated that participants who used portals were more likely to be active seekers than participants who did not use portals. (80.0% vs 36.2%).

DISCUSSION

PHIM has been described in various contexts24,46,49,50 but has not been holistically detailed for a healthy older adult population. This study highlights that a mixed methods approach facilitates a more holistic examination of the complex and varied work of PHIM. Guided by the Work System Model framework, we presented 5 key PHIM activities and varied approaches to these 5 activities as described by older adults. The approaches taken toward these activities are deeply influenced by characteristics of the older adult, and the sociotechnical factors of involvement of others, living situation, and technology use.

Most of our participants did not view PHIM as an isolated activity. PHIM processes and activities were well integrated into our participants’ lives, and the realities of their health, values, social environments, and living situations. Among older adults, PHIM varied by their level of organization, seeking health information, involvement of others, and degree of emergency planning. We originally hypothesized that older adults would fall into “styles” of PHIM based on their individual inclinations and habits. However, by looking at the broader context, our findings suggest that older adults’ approaches to PHIM depend heavily on context including their health, their social and physical environment, the tools they use, and their living situation. Older adults living independently were more likely to engage in PHIM than older adults in assisted living where PHIM work was generally transferred to staff. These results align with recent studies focusing on patient work, which describe patients and their family members engaged within their social, physical, and organizational contexts.25,31 While patient work seeks to support health, it can often be invisible to the medical community, and is thus crucial to understand and to incorporate into HIT.51

Over the last 20 years there has been increased focus on research related to successful aging, emphasizing the importance of social support systems, resilience, and autonomy.52,53 The goal for our participants in managing PHI was primarily to maintain wellness and independence and continue living fully for as long as possible. Most participants were not aware of performing PHIM activities because they were healthy and were more focused on activities they cared about, such as spending time with family and friends. Our interviews reinforced prior findings regarding the importance of incorporating wellness information into HIT systems for older adults.46 Although older adults lag behind younger adults in adopting new technologies9 many of our participants actively sought health information online, used patient portals, and owned cell phones. It is important to envision what an effective system to support PHIM would be for those facing the dynamic process of aging with potential physical and cognitive decline. Designing for older adults must also take into account the variety of approaches to PHIM activities as they relate to both maintaining health and monitoring illness. Current patient portals generally focus on the latter.

Approaches to PHIM activities are dynamic and sensitive to changes often outside the control of older adults, such as illness and changes in vision, mobility, memory, and support networks. These changes may require additional supportive technologies such as walkers or wheelchairs, care services, or asking for help from friends and family. Within our study, each PHIM approach taken was dependent on and interacted with personal habits, motivations, and goals. So, choices to pile or file were influenced by both organizational habits and decisions related to whether then information was “just-in-time,” “just-at-hand,” “just-in-case,” or “just-because.”54 Participants were motivated by what was easiest and best in terms of information storage and access at a particular point in time, often based on their needs for support and their perception of the usefulness, availability, accuracy and timeliness of the information.34 This was evident in patients who had had an acute illness or cancer and would carefully file PHI at one point in time and then stop when in remission, or participants who chose to use a patient portal while stopping their storage of paper-based health information. Participants’ choice to keep papers out in places where they would visually remind them to do a health related task was another easiest and best scenario. Effective HIT design must take into account the importance of understanding these points of intersecting influences when attempting to design for patient access to and retrieval of PHI. For example, based on our findings, it might be anticipated that most older adults will rarely check the patient portal when healthy and therefore the portal is not necessarily a good venue for routine communications or reminders to update emergency information.

Different forms of social support become important with aging and the impact of and need for PHIM support networks for older adults is clear.48,55 In our previous research, participants described varying levels of sharing of information and tasks, and differing sizes of PHIM support networks.48,56 We found that participants expressed varying needs for sharing PHIM activities based on their situation. For instance, older adults were more likely to allow involvement of others in their PHIM as they moved from independent living to retirement facilities, and from retirement facilities to assisted living. Those who were willing to share some information while continuing to manage their PHI either were sharing to augment their PHIM practices, or to keep the communication channels open for family and friends. As with other aspects of PHIM, these relationships were dynamic, often changing over time and depending on the situation. Children or friends that were listed as important at one point of time, could change because of moving, growing responsibilities, a falling out, or a newly formed connection.

Those who did not want to share information or PHIM expressed a desire to maintain independence and not burden others.57 As designers look at ways to support sharing and communication,58,59 it is important to remember that these needs and preferences are dynamic and are influenced by a variety of sociotechnical factors and contexts.30,60 Nearly all older adults wanted control over what, when, and with whom health information was shared. One design strategy that could support older adults as they plan for the future and think about the types of health information they would like to share is using “What if” videos, similar to what is available to help create advanced directives (https://prepareforyourcare.org/welcome). Such tools could help older adults think through who, what, and when they would like to share health information with others.

PHIM can be a burden.50 We found that consistently performing certain PHIM activities such as tracking or updating emergency planning materials was difficult. Our population was generally healthy and interested in PHIM to the extent that it maintained their health. Individuals tended to stop PHIM activities when they were acutely ill. This is consistent with findings by Ancker,50 who interviewed adults (mean age 64 years) with multiple chronic diseases and found that health information management was a burden for those who are ill or debilitated. PHIM systems must support the variable role others play in performing PHIM activities when individuals are not up for performing this work.50 Some older adults preferred not to anticipate decline or lack of wellness.61 This translated to a lack of preparing for future events, whether small disruptions such as minor illness, or large disruptions such as medical emergencies. There is a need for researchers and HIT designers to consider how to best encourage and support planning for future changes, particularly because research indicates that such planning can significantly impact quality of life.62

Limitations

Our findings are based on the results from in-depth interviews with older adults in Seattle, Washington. Although we actively sought participants from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds, the majority of our sample identified as non-Hispanic white. Results may not be generalizable to older adults from different geographic areas or racial or ethnic backgrounds. This research was formative and exploratory. The nature of the association between individual characteristics and PHIM approaches will require broader investigations. However, we had a relatively large sample size (N = 88). The credibility of our results is strengthened by member checking, with nearly half of eligible original participants responding to the feedback survey. On average, our purposive sample had a lower eHealth Literacy Scale score than a previously reported group of older adults recruited online.42 Given the selection bias that can occur from recruitment online, our sample may be more reflective of the broader older adult community.

CONCLUSION

Drawing on models of patient work systems, our mixed methods approach to investigating PHIM needs and practices among older adults revealed dynamic approaches to key PHIM activities. Approaches varied depending on internal and external factors within a sociotechnical system. PHIM tools that meet the needs of older adults should acknowledge the goal of maintaining health, the dynamics of aging, varied PHIM approaches, and the physical, organizational, and social contexts in which PHIM occurs.

FUNDING

The research presented here was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under award number R01HS022106. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AMT was the recipient of the grant (R01HS022106) and was responsible for the overall study design. AMT, KPO, ALH, and GD created the interview guide. KPO, JJ, JOT, and ALB collected and coded the transcript data. KPO, JOT, ALH, ALB, and AMT analyzed and interpreted the qualitative data. ISP, JOT, and AMT analyzed and interpreted the quantitative data. JOT, ALH, KPO, GD, ALB, and AMT contributed to drafting, writing, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors gave input to the final version and provided approval of the version to be published.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Jonathan Joe, PhD (JJ) for his contribution to conducting and coding in-depth interviews. We thank our participants and partnering organizations that made this study possible. In particular, we would like to thank Geraldine Wallace, who at 94 years of age patiently assisted us with instrument development and provided feedback about study materials and procedures throughout the research process.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pratt W, Unruh K, Civan A, et al. Personal health information management. Commun ACM 2006; 49 (1): 51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Civan A, Skeels MM, Stolyar A, et al. Personal health information management: consumers’ perspectives. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2006; 156–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, et al. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159 (10): 677–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Procter R, Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Sugarhood P, Rouncefield M, Hinder S.. The day-to-day co-production of ageing in place. Comput Supported Coop Work 2014; 23 (3): 245–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Consumer health IT applications. https://digital.ahrq.gov/key-topics/consumer-health-it-applications Accessed April 2020.

- 6. Gustafson D, McTavish F, Hawkins R.. Computer support for elderly women with breast cancer. JAMA 1998; 280 (15): 1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandl KD, Simons WW, Crawford WCR, et al. Indivo: a personally controlled health record for health information exchange and communication. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007; 7 (1): 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petullo B, Noble B, Dungan KM.. Effect of electronic messaging on glucose control and hospital admissions among patients with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016; 18 (9): 555–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wade-Vuturo AE, Mayberry LS, Osborn CY.. Secure messaging and diabetes management: experiences and perspectives of patient portal users. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20 (3): 519–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PEW Research Center. Technology use among seniors. 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/technology-use-among-seniors/ Accessed December 12, 2019.

- 11. Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med 2011; 8 (1): e1000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keasberry J, Scott IA, Sullivan C, et al. Going digital: a narrative overview of the clinical and organisational impacts of eHealth technologies in hospital practice. Aust Health Review 2017; 41 (6): 646–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Livingston G. Americans 60 and older are spending more time in front of their screens than a decade ago. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/18/americans-60-and-older-are-spending-more-time-in-front-of-their-screens-than-a-decade-ago/? utm_source=Pew+Research+Center&utm_campaign=041770d7ae-Internet-Science_2019_06_27&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_3e953b9b70-041770d7ae-400310621 Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 14. Clark S, Singer D, Solway E, et al. Logging in: Using patient portals to access health information. University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging. https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/report/logging-using-patient-portals-access-health-information Accessed February 28, 2020.

- 15. Wilson C, Peterson A.. Managing Personal Health Information: An Action Agenda (Prepared by Insight Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200710072T.) AHRQ Publication No. 10-0048-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

- 16. Mitzner TL, Savla J, Boot WR, et al. Technology adoption by older adults: findings from the PRISM trial. Gerontologist 2019; 59 (1): 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fields J, Cemballi AG, Michalec C, et al. In-home technology training among socially isolated older adults: findings from the Tech Allies Program. J Appl Gerontol 2020. Mar 6 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turner AM, Osterhage K, Hartzler A, et al. Use of patient portals for personal health information management: the older adult perspective. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2015; 2015: 1234–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jimison H, Gorman P, Woods S, et al. Barriers and drivers of health information technology use for the elderly, chronically ill, and underserved. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008; 175: 1–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim E-H, Stolyar A, Lober WB, et al. Challenges to using an electronic personal health record by a low-income elderly population. J Med Internet Res 200911 (4): e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siek KA, Ross SE, Khan DU, et al. Colorado Care Tablet: the design of an interoperable Personal Health Application to help older adults with multimorbidity manage their medications. J Biomed Inform 2010; 43 (5 Suppl): S22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lakey SL, Gray SL, Borson S.. Assessment of older adults’ knowledge of and preferences for medication management tools and support systems. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43 (6): 1011–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Findley A. Low health literacy and older adults: meanings, problems, and recommendations for social work. Social Work Health Care 2015; 54 (1): 65–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013; 56 (11): 1669–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holden RJ, Valdez RS, Schubert CC, Thompson MJ, Hundt AS.. Macroergonomic factors in the patient work system: examining the context of patients with chronic illness. Ergonomics 2017; 60 (1): 26–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carayon P. Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon 2006; 37 (4): 525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heinz M, Martin P, Margrett JA, et al. Perceptions of technology among older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 2013; 39 (1): 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumar S, Ureel LC, King H, et al. Lessons from our elders: identifying obstacles to digital literacy through direct engagement. In: proceedings of the 6th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (PETRA ’13); 2013: 1–8.

- 29. Carayon P. The balance theory and the work system model … Twenty years later. Int J Hum-Comp Int 2009; 25 (5): 313–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zayas-Cabán T. Health information management in the home: a human factors assessment. Work 2012; 41 (3): 315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Valdez RS, Holden RJ, Novak LL, et al. Transforming consumer health informatics through a patient work framework: connecting patients to context. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015; 22 (1): 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thielke S, Harniss M, Thompson H, Patel S, Demiris G, Johnson K.. Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs and the adoption of health-related technologies for older adults. Ageing Int 2012; 37 (4): 470–88. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weitzman ER, Kaci L, Mandl KD.. Sharing medical data for health research: the early personal health record experience. J Med Internet Res 2010; 12 (2): e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sun S, Belkin NJ.. Information attribute motivators of person health information management activities. Proc Assoc Info Sci Tech 2015; 52 (1): 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care 2002; 40 (9): 771–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D.. Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care 2005; 43 (6): 607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006; 46 (4): 503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, et al. Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy: decision making and information-seeking preferences among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med 1989; 4 (1): 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Norman CD, Skinner HA.. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J Med Internet Res 2006; 8 (4): e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42 (2): 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3 (2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chung SY, Nahm ES.. Testing reliability and validity of the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) for older adults recruited online. Comput Inform Nurs 2015; 33 (4): 150–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turner AM, Osterhage K, Hartzler, et al. Personal health information practices of older adults: one size does not fit all. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019; 264: 1995–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Turner AM, Osterhage KP, Taylor JO, et al. A closer look at health information seeking by older adults and involved family and friends: design considerations for health information technologies. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018; 2018: 1036–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Washington State Department of Health. Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST). https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/IllnessandDisease/PhysiciansOrdersforLifeSustainingTreatment Accessed February 28, 2020.

- 46. Hartzler AL, Osterhage K, Demiris G, et al. Understanding views on everyday use of personal health information: insights from community dwelling older adults. Inform Health Soc Care 2018; 43 (3): 320–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turner AM, Osterhage K, Loughran J, et al. Emergency information management needs and practices of older adults: a descriptive study. Int J Med Inform 2018; 111: 149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taylor JO, Hartzler AL, Osterhage KP, et al. Monitoring for change: the role of family and friends in helping older adults manage personal health information. J Am Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (8): 989–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Werner NE, Jolliff AF, Casper G, et al. Home is where the head is: a distributed cognition account of personal health information management in the home among those with chronic illness. Ergonomics 2018; 61 (8): 1065–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ancker JS, Witteman HO, Hafeez B, et al. The invisible work of personal health information management among people with multiple chronic conditions: qualitative interview study among patients and providers. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17 (6): e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Unruh KT, Pratt W.. The Invisible Work of Being a Patient and Implications for Health Care: “[the doctor is] my business partner in the most important business in my life, staying alive. Conf Proc Ethnogr Prax Ind Conf 2008; 2008 (1): 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tkatch R, Musich S, MacLeod S, et al. A qualitative study to examine older adults’ perceptions of health: keys to aging successfully. Geriatr Nurs 2017; 38 (6): 485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reichstadt J, Depp CA, Palinkas LA, et al. Building blocks of successful aging: A Focus Group Study of older adults’ perceived contributors to successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 15 (3): 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moen A, Brennan P.. Health@Home: The Work of Health Information Management in the Household (HIMH): implications for Consumer Health Informatics (CHI) innovations. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005; 12 (6): 648–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ohs J, Yamasaki J.. Communication and successful aging: challenging the dominant cultural narrative of decline. Commun Res Trends 2017; 36 (1): 4–41. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petrescu-Prahova M, Osterhage K, Taylor JO, et al. Older adult health-related support networks: implications for the design of digital communication tools. Innov Aging 2020; 4 (3). doi: 10.1093/geroni/igaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crotty BH, Walker J, Dierks M, et al. Information sharing preferences of older patients and their families. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175 (9): 1492–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hartzler A, Skeels MM, Mukai M, et al. Sharing is caring, but not error free: transparency of granular controls for sharing personal health information in social networks. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011; 2011: 559–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Caine K, Hanania R.. Patients want granular privacy control over health information in electronic medical records. J Am Inform Assoc 2013; 20 (1): 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brennan PF, Casper G.. Observing health in everyday living: ODLs and the care-between-the-care. Pers Ubiquit Comput 2015; 19 (1): 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barbour JB, Rintamaki LS, Ramsey JA, Brashers DE.. Avoiding health information. J Health Commun 2012; 17 (2): 212–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nussbaum JF. Life span communication and quality of life. J Commun 2007; 57 (1): 1–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.