Abstract

Background:

As people age, their mobility begins to decrease. In an effort to maintain mobility, this population can seek out rehabilitation services with the goal of improving their driving. However, it is unclear who has sought out rehabilitation for this purpose.

Objective:

To better understand, identify, and describe the characteristics of older adults who utilize rehabilitation with the purpose of improved driving.

Methods::

Data was analyzed from the fifth round of the National Health and Aging Trends study (NHATS), which is made up of Medicare beneficiaries over the age of 65 that are community-dwelling. Rehabilitation utilization specifically for improved driving and other transportation was analyzed. Adjusted weighted logistic regression was conducted to better understand and identify the characteristics of the study population that received rehabilitation services for the purpose of improved driving ability.

Results:

Nineteen percent (N=1,335) of this cohort received rehabilitation in the past year. Of those, 10% (N=128) received rehabilitation to specifically improve driving and 2% (N=25) did so to improve other transportation. Older adults who were single, separated, or never married were less likely to use rehabilitation for improving driving ability, compared to older adults who were married (OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.11 – 0.80).

Conclusion:

Older adults who are married were more likely to report they wanted to improve their driving ability with rehabilitation. The role of rehabilitation services to improve driving among older adults will play a key role in the coming years as older adults strive to maintain their independence.

Keywords: Automobile driving, Rehabilitation, Aged

Introduction

The negative impact of driving cessation upon the wellbeing of older adults is greatly understood, but the strategies to delay driver cessation among this population are not as widely examined. An inverse relationship exists when comparing mobility to increasing age. Among older adults, mobility is defined through the ecological model of adaption as:

“The ability to move oneself (either independently or using assistive device or transportation) within environments that expand from one’s home to the neighborhood and regions beyond”1

This ability to move is closely associated with driving. 1 Mobility via transportation, such as driving of a personal vehicle, is necessary to keep older adults’ independence. 2 This ability to drive becomes even more important as older adults move to suburban and rural areas in which public transportation is lacking or nonexistent.3 The lack of resources perpetuates self-reliant behavior without accounting for the decline of functional mobility among the aging population.

The decrease in mobility results in a decrease in ability to drive.4 Driving cessation – is due to the self-regulation as well as physical limitations of older adults.5 For example, some older drivers avoid driving in unknown locations or on highways in an attempt to limit these risky situations; this strategy is associated with the successful aging theory.6 A hesitancy and cautiousness to drive among older adults is rational. Statistics show that this specific population has higher crash rates based on distance driven compared to younger drivers and a higher mortality rate in such crashes.4–5 This is not to say all older adults are bad drivers, but with increased age is increased risk, “for drivers older than age 80, the risk of a fatal crash is as much as four times greater.”7

Developing sound strategies to address driving among older adults is becoming increasingly imperative as the natural aging of the population occurs. When thinking of such strategies, one should acknowledge the need to “balance older driver safety and mobility-related independence”.8 Understanding that we cannot prevent older adults from aging, nor can we implement a mandate to halt driving in older adults, we must constructively think about mobility in the aging population. The question becomes; how can we prevent mobility decline for older adults and what steps are necessary to do so. One of the main goals of rehabilitation is to improve mobility disability.

Gell, Mroz, and Pate (2017) aimed to quantify the utilization of rehabilitation services – which include physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy – in older adults using the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS).9 Gell and her team found that 20% of older adults in the U.S. reported using rehabilitation in the past year.9

The downstream impact of rehabilitation services on the aging population is increasingly important to examine. Not only are older adults improving their physical function, those abilities are applicable to all facets of life, including ability to drive. Among persons using rehabilitation services, driving is prioritized as an extremely valued goal.10 This study aims to explore the utilization of rehabilitation services for the purpose of self-reported improvement in driving ability among older adults as well as rehabilitation to improve the use of other forms of transportation using the NHATS cohort.

Methods

Study Population

The NHATS cohort is comprised of a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries, ages 65 and older. The NHATS data is collected by conducting in-person interviews with the sampled person (SP) on an annual basis. Data collection began in 2011 and the original cohort was replenished to account for attrition in 2015 (Round 5). The 2015 interview (Round 5) also included for the first time questions on utilization of rehabilitation services.

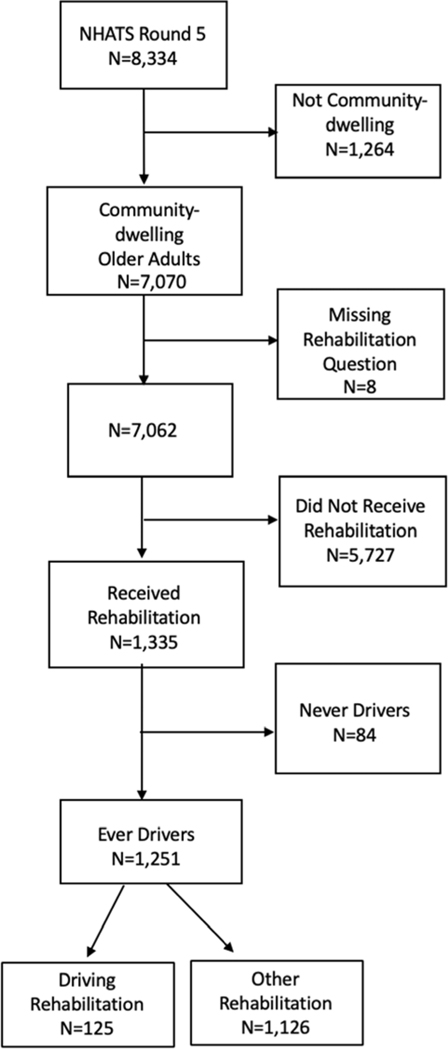

This cross-sectional study was limited to community-dwelling older adults in Round 5 of NHATS (N=7,062). Self-report rehabilitation was derived from asking participants if they “received rehab in last year” ( rehab services were described as those that can help you improve function and the ability to carry out daily activities including physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy) which allowed for the following dichotomous responses: “yes” or “no”. After non-community-dwelling adults were excluded (N=1,264) and those that did not respond to the question regarding rehabilitation (N=8) were removed, 1,335 community-dwelling older adults said they used rehabilitation services in the past year, compared to 5,727 respondents that did not use rehabilitation services in the past year (Figure 1). A second analysis was conducted on those that received rehabilitation services in the past year to investigate the characteristics of older adults that received rehabilitation services to improve their driving or other transportation related difficulties. The final regression model excluded individuals who had never driven (N=84).

Figure 1.

Population Flow Diagram

Demographic and Health Characteristics

Demographics characteristics included gender, age, race, education level and marital status. The variables were used in the analysis as follows: age (65–69; 70–74; 75–79; 80–84; 85–89; 90+), race (White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; other; Hispanic), highest education level (below a high school education; high school or equivalent education; at least a bachelor’s degree). Lastly, a participant’s marital status was categorized as: (1) married or living with a partner, (2) separate, divorced, widowed, never married.

Health characteristics included health, self-report depression, and performance-based physical function. Because some of these variables were collected in earlier rounds, education level was taken from Round 1. Health conditions (comorbidities) were recorded through self-reporting of the following; heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, and/or cancer. Data on health conditions in Round 5 includes both conditions newly reported at that round and some chronic conditions reported in previous rounds (e.g. arthritis). Round 5 new conditions and previously reported chronic conditions were used to develop a count of each sample person’s comorbidities, which was then dichotomized as low (≤ 2) and high (more than two). Dementia/Alzheimer’s disease (categorized as probable, possible, no) was included as a separate variable and not included in the comorbidity count. For more detailed information on development of the dementia/Alzheimer’s disease classification variable from reports of diagnoses, proxy informant reports, and cognitive tests in NHATS see NHATS’ technical paper 5.11 To assess self-reported depression symptoms, participants were asked how often in the past month they felt down, depressed, or hopeless and how often they had little pleasure in doing things and provided one of the following responses: (1) not at all, (2) several days, (3) more than half the days, (4) nearly every day. The responses to these questions were assigned values (1–4 as written above) and combined for a possible score of 2–8. Participants who scored 3 or greater were reported as having symptoms of depression.1

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score, measures physical functioning such as strength and balance. This performance-based battery is a composite score of “(1) three standing balance tests (side by side, semi-tandem, and full-tandem), (2) repeat chair stands (5 times) and (3) walking speed on a 3-m course allowing walking aids but not wheelchair or scooter.12 Scores range from 0 (not attempted) to 12 (best) (additional information on procedures and scores can be found on the NHATS website), and for the purpose of this study was categorized into three groups of scores ranging from low to high (scores: 0–3, 4–7, 8–12).13

Outcome

Rehabilitation to improve driving ability was recorded through a self-reported response in the Round 5 (2015) survey question “Please look at this card and tell me which of these were you trying to improve?” in which one of the categorical options was “improve driving”. This variable was dichotomized (yes/no) and serves as the outcome measure in an attempt to describe who receives rehabilitation specifically to improve driving.

Secondary Outcome

Rehabilitation to improve using other transportation was another option respondents could have chosen for the above question and was dichotomized (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

The first stage of the analysis incorporated descriptive statistics, which examined the population distribution of demographics, health conditions, and health characteristics stratified by those that received rehabilitation services in the past year compared to those that have not (Table 1).

Table 1:

NHATS Round 5 Utilization of Rehabilitation Services for Improved Driving, Improving Other Transportation Uses, and Other Purposes (N=1,335)ǂ

| % Rehabilitation to Improve Driving (N=128) | SE of % | % Rehabilitation to Improve Other Transportation Modes Usages (N=25) | SE of % | % Rehabilitation for Other Purposes (N=1,182) | SE of % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (N=1,335) | 65 to 69 | 25.27 | 4.53 | 51.14 | 11.75 | 23.35 | 1.49 |

| 70 to 74 | 35.12 | 5.22 | 16.18 | 7.99 | 28.45 | 1.44 | |

| 75 to 79 | 21.23 | 3.99 | 15.31 | 9.65 | 18.82 | 0.98 | |

| 80 to 84 | 10.96 | 2.77 | 11.23 | 6.88 | 14.51 | 0.95 | |

| 85 to 89 | 4.51 | 1.29 | 3.64 | 2.63 | 8.01 | 0.61 | |

| 90+ | 2.91 | 1.13 | 2.51 | 1.88 | 4.87 | 0.45 | |

| Gender (N=1,335) | Female | 55.09 | 6.34 | 55.69 | 13.45 | 59.79 | 1.50 |

| Race/Ethnicity (N=1,299) | White, non-Hispanic | 85.02 | 3.85 | 73.60 | 10.76 | 85.10 | 1.00 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6.66 | 2.17 | 6.79 | 3.50 | 6.67 | 0.46 | |

| Other | 4.13 | 2.16 | 5.27 | 5.76 | 2.82 | 0.72 | |

| Hispanic | 4.19 | 2.80 | 14.33 | 8.69 | 5.42 | 0.55 | |

| Education Level (N=1,335) | Less than high school | 15.28 | 3.79 | 25.39 | 10.17 | 16.15 | 1.26 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 51.67 | 5.02 | 37.26 | 13 | 50.76 | 1.77 | |

| Bachelor’s degree and higher | 33.05 | 4.65 | 37.36 | 12.4 | 33.09 | 1.68 | |

| Marital Status (N=1,335)* | Married or living with a partner | 72.33 | 4.23 | 33.39 | 12.98 | 56.06 | 1.61 |

| Separated, divorced, or never married | 8.83 | 2.94 | 39.28 | 13.51 | 17.38 | 1.25 | |

| Widowed | 18.85 | 3.83 | 27.33 | 10.92 | 26.56 | 1.31 | |

| Short Physical Performance Battery (N=1,236) | Low (0 to 3) | 29.70 | 5.84 | 35.4 | 11.47 | 27.87 | 1.35 |

| Medium (4 to 7) | 34.60 | 5.87 | 25.61 | 11.22 | 29.17 | 1.53 | |

| High (8 to 12) | 35.70 | 6.76 | 38.99 | 13.23 | 42.96 | 1.65 | |

| Symptoms of Depression (N=1113) | Yes | 52.14 | 5.47 | 53.93 | 12.62 | 49.35 | 1.72 |

| Comorbidity Count (1,311) | 3 or more | 55.79 | 4.31 | 38.16 | 12.8 | 50.80 | 1.95 |

| Dementia/Alzheimer’s (N=1,335) | Probable/possible | 6.20 | 1.81 | 14.61 | 8.49 | 10.08 | 0.79 |

Weighted analysis

Significant at an alpha level of 0.05

Then a secondary descriptive analysis was completed for those that have received rehabilitation services in the past year (N=1,335) by demographic and other characteristics stratified by the purpose of the rehabilitation services – to improve driving compared to rehabilitation for other reasons (Table 2). If respondents chose both rehabilitation to improve driving and to improve other forms of transportation, they were counted as reporting rehabilitation to improve driving. If they did not choose either rehabilitation to improve driving or rehabilitation to improve other forms of transportation, they were categorized as other rehabilitation. The univariate analysis was conducted using the Rao-Scott chi-squared test, Due to the complex survey design replicate weights were used in all analyses using the modified balance repeated replication method.

Table 2.

Weighted Multiple Logistic Regression Comparing Rehabilitation Utilization to Improve Driving Ability (N=125) to Rehabilitation for Other Purposes (N=1,126), Excluding Never Drivers

| Total N=1,251 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR Estimates | 95% Confidence Intervals | ||

| Age | 65 to 69 (ref) | - | - |

| 70 to 74 | 1.09 | (0.58, 2.05) | |

| 75 to 79 | 0.88 | (0.42, 1.86) | |

| 80 to 84 | 0.59 | (0.25, 1.42) | |

| 85 to 89 | 0.45 | (0.18, 1.10) | |

| 90+ | 0.64 | (0.20, 2.03) | |

| Gender | Female | 1.15 | (0.67, 1.98) |

| Race | White, non-Hispanic (ref) | - | - |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.17 | (0.49, 2.82) | |

| Other | 1.71 | (0.39, 7.47) | |

| Hispanic | 0.88 | (0.13, 6.04) | |

| Education Level | Little-to-no schooling completed | 1.00 | (0.42, 2.41) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 1.01 | (0.56, 1.80) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher (ref) | - | - | |

| Marital Status | Married or living with partner (Ref) | - | - |

| Living alone, separated, divorced, or never married | 0.29 | (0.11, 0.80) | |

| Widowed | 0.60 | (0.32, 1.13) | |

| Short Physical Performance Battery | 0 to 3 (ref) | - | - |

| 4 to 7 | 1.01 | (0.52, 1.96) | |

| 8 to 12 | 0.57 | (0.22, 1.47) | |

| Depression | Yes | 1.24 | (0.70, 2.18) |

Once these descriptive analyses were completed, a test to assess correlation of the predictor variables was conducted. Due to the small number of participants in the rehabilitation to improve other transportation category, these individuals were combined with the other rehabilitation services group. After excluding those respondents that reported never driving in the past, the predictor variables were then specified for the model. Logistic regression incorporating weights and sample design variables was used to investigate the impact of demographics and other characteristics on rehabilitation specifically to improve driving compared to other rehabilitation.

Results

The descriptive characteristics of the community-dwelling NHATS Round 5 population that received and did not receive rehabilitation services during the survey period were compared (data not shown). Characteristics include frequencies, totals, and standard errors, all of which are representative of the Medicare beneficiary population across the United States. Out of the 7,062 community-dwelling-older adults, 19% (N=1,335) reported receiving rehabilitation in the past year. Of the sampled population that received rehabilitation services in the past year, about 55% are between the ages of 65–74, 59% are female, and 82% are white, non-Hispanic. In terms of education, the majority of this population has graduated from high school (84%). Of those who received rehabilitation services, more than 57% of the population is married and about 50% had symptoms of depression.

Table 1 explores the descriptive statistics of respondents who participated in rehabilitation geared specifically at improving their driving ability and those who participated in rehabilitation to improve other transportation among those who received rehabilitation services (N=1,335) in the past year. Out of the 1,335 respondents that reported receiving rehabilitation in the past year, 10% (N=128) reported receiving rehabilitation specifically to improve driving. Two percent (N=25) of the respondents who utilized rehabilitation services in the past year, reported using rehabilitation to improve their use of other transportation. Respondents between the ages of 65–69 years made up 25% of respondents that used rehabilitation to improve driving compared to 51% of respondents that used rehabilitation to improve other transportation. Eighty-five percent of respondents who received rehabilitation to improve driving were white, non-Hispanic, compared to 74% of participants that received rehabilitation for other transportation. Eighty-five percent of participants who used rehabilitation to improve driving had a high school diploma compared to only 75% of those who received rehabilitation to improve other transportation. Of those who received rehabilitation to improve driving, 56% reported having at least three chronic health conditions compared to only 38% of individuals that received rehabilitation for other transportation. Although a higher percent of respondents who received rehabilitation to improve driving were married (72%) this was not the case for respondents who received rehabilitation for other transportation related services (33%). Respondents that received rehabilitation for driving (52%) and other transportation (54%) reported feeling depressed simultaneously while only (49%)of respondents that reported utilizing rehabilitation for other purposes reported feeling depressed in the past year. Marital status was the only variable that significantly differed depending on the type of rehabilitation received.

In table 2, dementia/Alzheimer’s as well as comorbidity count did not contribute to the model and were both removed. The final weighted logistic regression model includes rehabilitation to improve driving as the outcome and age, gender, race, education level, marital status, symptoms of depression, and SPPB.

Table 2 reports the results of the logistic regression using round 5 analytic weights. After excluding respondents that reported never driving, 10% of participants reported receiving rehabilitation specifically to improve driving. Marital status was found to be associated with the utilization of rehabilitation services for the purpose of improved driving, after adjusting for the other variables in the model. Respondents who were living alone, separated, divorced or never married had a lower odds of receiving rehabilitation to improve driving compared to those who were married or living with a partner (OR: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.11, 0.80) Respondents who were widowed had a lower odds of receiving rehabilitation to improve driving compared to those who were married or living with a partner but this was not statistically significant (OR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.32, 1.13).

Discussion

Rehabilitation specifically to improve driving accounted for 10% of rehabilitation services reported by older adults. Older adults who were married were more likely to use rehabilitation services specifically to improve driving compared to those living alone, separated, divorced, or never married. Although a larger proportion of those who received rehabilitation services to improve driving were married, a larger proportion of those who received rehabilitation services to improve other forms of transportation were single. Rehabilitation to improve driving did not differ from rehabilitation for other reasons by any of the characteristics assessed other than marital status.

As previously mentioned, driving provides a means, literally a vehicle, in which older adults can travel and be an active member of a social network. When older adults lose their spouses, it may be an important time to evaluate driving rehabilitation in order to help older adults maintain their independence and to stay engaged in their social network.

The loss of independence and mobility is not limited to driving cessation alone, rather it can be expanded to the broader access to transportation. Over half of transportation-dependent older adults have unmet transportation needs which results in their sole dependency on family to provide transportation.14 Unfortunately, not all older adults have the family support that allows them the luxury of “discretionary trips”, thus resulting in decreased quality of life and negative lifestyle changes among this population.15 Even though many older adults reside in suburbs, where the primary transportation is driving, transportation-planning agencies are expanding their attention to the aging population and their access to transportation.16 As the aging population continues to grow, the implications of poor transportation access, whether it be public or agency developed, could be a potential public health crisis.

It is important to note the limitations of this study. For example, we are limited in the number of sampled persons that reported seeking rehabilitation services for the purpose of improved driving (about 0.2% of the total NHATS population in Round 5). The small sample size of those receiving rehabilitation specifically for driving may account for the limited number of statistical differences in the demographic, functional, and health characteristics found between older adults reporting rehabilitation to improve driving compared to other types of rehabilitation. As this is the first round of NHATS that included rehabilitation services, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis. It is unknown how long participants received rehabilitation to improve their driving. It is also difficult to determine the temporal relationship between the characteristics described throughout this study and utilization of rehabilitation to improve driving.

Strengths of this study include the importance and unique opportunity the Round 5 data collection captured. This is the first round of data collection in NHATS, a large nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries that asked about rehabilitation services. This will prove essential when quantifying the importance of rehabilitation services for the Medicare population especially for the purpose of improved driving. Future analyses can aggregate receipt of rehabilitation for improved driving across rounds, increasing sample sizes and expanding the characteristics that can be examined as associated with this type of rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Marital status was associated with rehabilitation utilization specifically to improve driving. The death of a spouse may be a prudent time to assess the need for driving rehabilitation. If continued driving is not the optimal outcome after the death of a spouse, then evaluating the older adult’s transportation access is paramount in order to maintain an older adult’s community mobility independence.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety’s Longitudinal Research on Aging Drivers (LongROAD) Project. It was also supported in part by the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) which is sponsored by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG032947) through a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Abbreviations:

- NHATS

National Health and Aging Trends Study

- OR

odds ratio

- SP

sampled person

- SPPB

Short Physical Performance Battery

Footnotes

Ethics:

This study presents results from secondary analysis of the NHATS dataset, which is deidentified and made available through registration with NHATS. The authors did not collect data or obtain consent from the participants. NHATS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and conducted by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Choi NG, & DiNitto DM (2015). Depressive symptoms among older adults who do not drive: association with mobility resources and perceived transportation barriers. The Gerontologist, gnu116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickerson AE, Molnar LJ, Eby DW, Adler G, Bedard M, Berg-Weger M, & Page O. (2007). Transportation and aging: A research agenda for advancing safe mobility. The Gerontologist, 47(5), 578–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbloom S. (2012). The travel and mobility needs of older people now and in the future In Coughlin JF & D’Ambrosio LA (Eds.), Aging America and transportation: Personal choices and public policy (pp. 39–54). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaheen SA, & Niemeier DA (2001). Integrating vehicle design and human factors: minimizing elderly driving constraints. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 9(3), 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldock MRJ, Mathias JL, McLean AJ, & Berndt A. (2006). Self-regulation of driving and its relationship to driving ability among older adults. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 38(5), 1038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonin-Guillaume S. (2010). Elderly drivers: Assessing performance or predicting driving safety. European Geriatric Medicine, 1(2), 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickerson AE, Meuel DB, Ridenour CD, & Cooper K. (2014). Assessment tools predicting fitness to drive in older adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), 670–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betz ME, Dickerson A, Coolman T, Schold Davis E, Jones J, & Schwartz R. (2014). Driving rehabilitation programs for older drivers in the United States. Occupational therapy in health care, 28(3), 306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gell NM, Mroz TM, Patel KV. (2017). Rehabilitation Services Use and Patient Reported Outcomes among Older Adults in the United States, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickerson AE (2013). Driving assessment tools used by driver rehabilitation specialists: Survey of use and implications for practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(5), 564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper Judith D., Freedman Vicki A., and Spillman Brenda. (2013). Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Technical Paper #5. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; Available at www.NHATS.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun DQ, Huang J, Varadhan R, & Agrawal Y. (2016). Race and fall risk: data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). Age and ageing, 45(1), 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Accessed September 2017]. www.nhats.org.

- 14.Cvitkovich Y, & Wister A. (2001). The importance of transportation and prioritization of environmental needs to sustain well-being among older adults. Environment and Behavior, 33(6), 809–829. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey JA (2007). Older people and transport: coping without a car. Ageing & Society, 27(1), 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levasseur M, Généreux M, Bruneau JF, Vanasse A, Chabot É, Beaulac C, & Bédard MM (2015). Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighborhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: results from a scoping study. BMC public health, 15(1), 503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]