Abstract

Pluripotency and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are marked by core transcription regulators such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog. Another important marker of pluripotency is the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). Here, we ind that a novel long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) Lx8-SINE B2 is a marker of pluripotency. LncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 is enriched in ESCs and downregulated during ESC differentiation. By rapid amplification of cDNA ends, we identified the full-length sequence of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. We further showed that transposable elements at upstream of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 could drive the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. Furthermore, ESC-specific expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 was driven by Oct4 and Sox2. In summary, we identified a novel marker lncRNA of ESCs, which is driven by core pluripotency regulators.

1. Introduction

Most of the mammalian genome is composed of noncoding sequences. Among them, transposable elements (TEs) contribute to ~40% of the genome [1]. The majority of TEs are silenced, however, a small percentage of TEs are expressed during development and in diseases [2]. They play multiple roles in these processes, including function as enhancers, promoters, and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) [3–6]. In vertebrates, 70% lncRNAs are composed of TEs [7]. TEs also confer tissue-specific expression on lncRNAs through the recruitment of transcription factors [3, 4, 6]. TE-derived lncRNAs actively participate in development. TE-derived lncRNA ROR functions as a sponge to miRNA and also works with hnRNPA1 to promote c-Myc expression during reprogramming [8–10]. Endogenous retrovirus HERVH-derived lncRNAs maintain pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells [3, 11–13]. Asymmetrical expression of ERV1 and ERVK-derived lncRNA LincGET in two- to four-cell mouse embryos biases cell fate toward inner cell mass [14]. These findings all suggest an important role of TE-derived lncRNA in development. Most of these findings are based on human cell lines. We are still lack of understanding of TE-derived lncRNAs in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs). In this study, we investigated the expression and regulation of one representative lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 in ESCs.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Mouse ESCs (E14) were cultured on plates coated with 0.2% gelatin (G1890, Sigma) in medium with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS, SH30070.03, Hyclone), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P1400, Solarbio), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (M3148–250, Sigma), and 10 ng/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; Z03077, GenScript). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and 3 -T3 cells were maintained on plates (703001, NEST Biotechnology) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in CO2 incubator.

2i culture medium contain 50% DMEM/F12 (BasalMedia), 50% Neurobasal media (Gibco), 1% N2 supplement, 1% B27 (Gibco), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine(Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P1400, Solarbio), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (M3148–250, Sigma), 1 μM MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (T6189, TargetMol), and 3 μM GSK3 inhibitor CHIR99021 (2520691, BioGems). 10 ng/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; Z03077, GenScript) was added for 2i/LIF condition.

2.2. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted with RNAiso Reagent (B9109, Takara) as described [15] and treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA in DEPC water (B501005, Sangon Biotech). The cDNA synthesis was carried out in RNase-free tubes (401001, NEST Biotechnology) with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (4897030001, Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) reactions were performed using the Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (H97410, Yeasen) in a QuantStudio 6 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Primer sequences for qPCR analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for qPCR analysis.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 | GCTGTTATGACTTGTTTCCTGGT | CTCTTCCTTGCAGGCTTAGAAC |

| Oct4 | GTGGAAAGCAACTCAGAGG | GGTTCCACCTTCTCCAACT |

| Sox2 | GCGGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCC | CGGGAAGCGTGTACTTATCCTT |

| Nanog | TTGCTTACAAGGGTCTGCTACT | ACTGGTAGAAGAATCAGGGCT |

| Esrrb | GCACCTGGGCTCTAGTTGC | TACAGTCCTCGTAGCTCTTGC |

| Prdm14 | CTCTTGATGCTTTTCGGATGACT | GTGACAATTTGTACCAGGGCA |

| Lysmd3 | ACGGTTTCCCTCCCAGGAAT | CATCAAGTCTATCTCTCGATGCG |

| Adgrv1 | CAGCCCTGAATCACTCTTCGT | CCCATCCAGGTCCGAGTCTA |

| LINE1 | GGACCAGAAAAGAAATTCCTCCCG | CTCTTCTGGCTTTCATAGTCTCTGG |

| SINE B2 | GAGTAAGAGCACCCGACTGC | AGAAGAGGGAGTCAGATCTCGT |

2.3. Depletion of Gene Expression with shRNAs

For gene knockdown, short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) for luciferase (control) or target genes were designed by an online tool (http://sirna.wi.mit.edu/) and synthesized by GENEWIZ corporation. The shRNA plasmids were constructed using the pSuper-puro system and purified with a kit (1211-01, Biomiga). mESCs were transfected with DNA using Polyjet (SL100688, SignaGen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transfected ESCs were selected with 1 μg/ml puromycin from 24 h after transfection. After four days of puromycin selection, transfected cells were harvested. The sequences of shRNAs are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Targeting sequences of shRNAs.

| Gene | shRNA target sequence |

|---|---|

| Oct4 shRNA | GTGGAAAGCAACTCAGAGG |

| Sox2 shRNA | GCGGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCC |

| Nanog shRNA | TTGCTTACAAGGGTCTGCTACT |

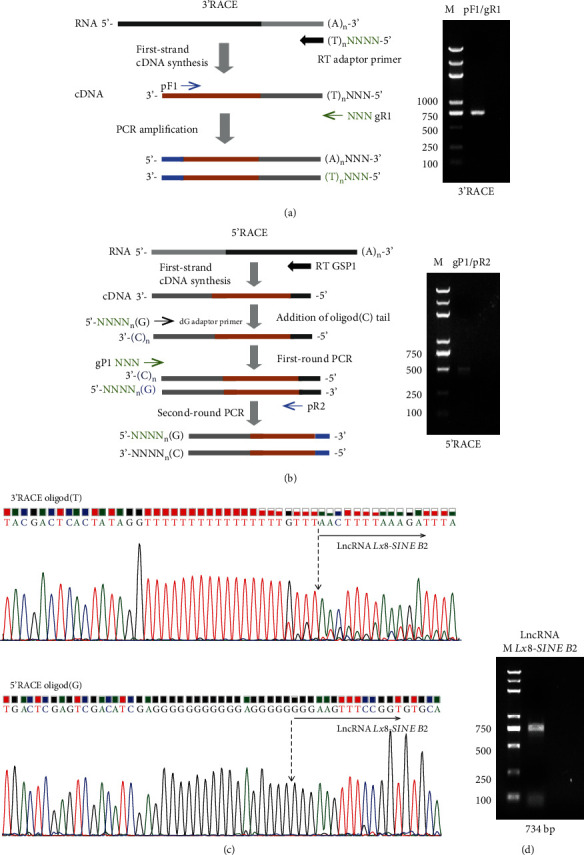

2.4. 5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) Analysis

For 3′ RACE, first-strand cDNA synthesis is initiated at the poly(A) tail of total RNA using the anneal oligo(dT)-containing RT Adapter Primer (AP) to mRNA. Gene-specific primer pF1 was designed based on the known sequence. 3′ fragment was amplified by primer pF1 and general primer gR1, the RACE PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel.

For 5′ RACE, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a gene-specific primer (RT GSP1), which was designed according to the 3′ known sequence. A homopolymer tail was subsequently added to the 3′-end of the cDNA using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase kit (2230A, Takara), according to the manufacturer's instruction. First-round PCR was performed based on poly(C) tail designed dG adaptor primer to synthesize double-stranded cDNA. Then, general primer gP1 and gene-specific primer pR2 were used for second-round PCR to amplify the cDNA 5′ end sequence. The RACE PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and cloned into pEASY-T1 (TransGen Biotech) for Sanger sequencing. The gene-specific RACE primers used for mapping each end were from Sangon Biotech and were listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

RACE primers.

| RACE primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| RT-adaptor primer | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGG(T)18VN |

| gR1 | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGAC |

| pF1 | ATACCTTCCTAAAACTAATGTGGACT |

| RT GSP1 | TGAAGAACTTTTAGCACAGCAGC |

| dG-adaptor primer | GACTCGAGTCGACATCGAGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG |

| gP1 | GACTCGAGTCGACATCG |

| pR2 | CAACTGTTCTAAACGCTTCTTAG |

2.5. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

Mouse ESCs were seeded at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate. Luciferase assay was performed as previously described [16]. The total amount of 200 ng of the various promoters of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 or pGL4.23 empty vector was transfected into each well of E14 ESC on a 24-well plate together with 10 ng of pCMV-Renilla. The medium was changed 12 h after transfection. After transfection of 36 h, cells were collected and lysed in 1x passive lysis buffer. The luciferase activity was determined by Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (#E1910, Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with Student's t-test (two-tailed). Significant differences were defined as ns for nonsignificant, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping the Full-Length Sequence of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2

Through mining the previous publication [17], it was shown that lincRNA-1282 was expressed in ESCs and its depletion leads to downregulation of c-Myc [17], which is an important reprogramming factor. Therefore, we set out to perform RACE to identify the full-length of lincRNA-1282 [17], which is a partial sequence of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. To identify the full length of Lx8-SINE B2, we performed 3′ RACE and 5′ RACE with primers as designed (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Our amplicons for both 5′ and 3′ RACE were visible as a single DNA band without multiple or unspecific bands (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Next, we sequenced the amplicons and identified the sequences of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 (Figure 1(c)). With the 5′ and 3′ ends of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 found, we designed primers to amplify the full length of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 and subcloned the lncRNA into TA cloning vector (Figure 1(d)). The lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 was revealed to be a 734 bp lncRNA.

Figure 1.

Mapping the full-length sequence of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. (a) Schematic of the 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (left) and 3′ RACE result for lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 (right). (b) Schematic of the 5′ RACE and its result for lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. (c) DNA sequencing of RACE using a universal primer in pEASY-T1 vector. (d) Validation of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 transcript size by PCR from cDNA. M, DNA marker.

3.2. Expression Pattern of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2

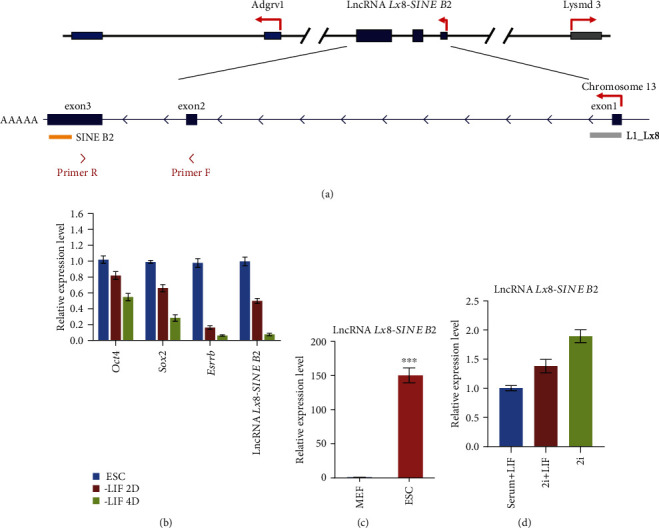

We searched the sequences of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 against the mouse genome (mm10) and discovered that lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 contained 3 exons, which are located between Adgrv1 and Lysmd3 gene (Figure 2(a)). Exon 1 of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 overlapped with LINE1 family Lx8 and its third exon overlapped with SINE B2 (Figure 2(a)); therefore, we named this lncRNA as Lx8-SINE B2. We designed primers on the nonrepeat region of exon 2 and 3 to detect the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. Interestingly, it is noticed that lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2was downregulated during ESC differentiation, similar to the pluripotency gene Oct4, Sox2, and Esrrb, according to qPCR results (Figure 2(b)). We also found that lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 was also expressed in ESCs instead of differentiated cells such as MEF (Figure 2(c)). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2was not affected by the alternation of ESC culture condition. Its expression was slightly upregulated in the presence of 2i/LIF or 2i condition in contrast to the serum/LIF culture condition (Figure 2(d)). These suggest lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 as a marker of ESC.

Figure 2.

Genomic location and expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. (a) Schematic of the mouse lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 locus on chromosome 13. lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 is between Adgrv1 and Lysmd3. There are three exons and some retrotransposon fragments of LINE or SINE in lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. RT–qPCR primers were indicated below. (b) The expression level of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2, Oct4 Sox2, and Esrrb in mESCs in the presence or absence of LIF for 2-4 days, as measured by RT–qPCR and normalized to Gapdh levels. Biological-triplicate data (n = 3 dishes) are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (c) qPCR analysis of the expression level of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 in mouse ESCs and MEF cells. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 according to two-sided Student's t-test (d) Expression analysis of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 in ESCs cultured under serum/LIF, 2i/LIF or 2i condition. Biological-triplicate data (n = 3 extracts) are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

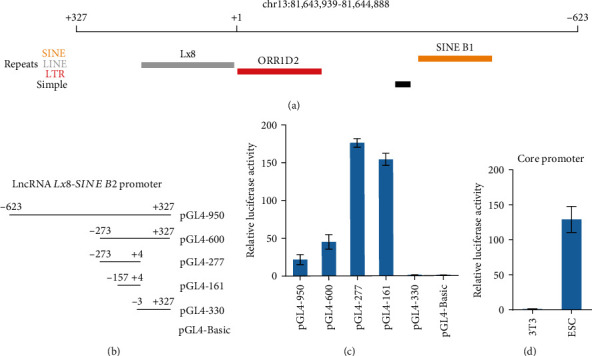

3.3. Promoter Structure of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2

After that, we examined how the specific expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 was achieved. The upstream 1 kb promoter region of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 contains ORR1D2 and SINE B1 (Figure 3(a)). To study how Lx8-SINE B2 is regulated in ESCs, we cloned -623 bp to +327 bp of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 gene into luciferase reporter (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). We also created various truncation versions of this region to identify the core promoter of Lx8-SINE B2 (Figure 3(b)). The region corresponding to ERV, origin-region repeat 1 type D2 (ORR1D2, -157 bp to +3 bp) carried the strongest promoter activity in contrast to those of other truncations (Figure 3(c)). The promoter activity of ORR1D2 was specific to ESCs but inactivated in 3T3 fibroblasts (Figure 3(d)). These results support that lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 is driven by ERV ORR1D2, implicating that TEs not only contribute to the exons of lncRNAs but also the promoter of lncRNAs.

Figure 3.

Dissection of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 promoter region. (a) Schematic of the positions of TEs on according to mouse mm10 genome the promoter region of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. (b) Schematic of various length fragments of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 promoter constructs. (c) Activities of various length fragments of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 promoter constructs were determined by luciferase reporter gene assays in E14 ESCs. Biological-triplicate data (n = 3 dishes) are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (d) Luciferase assay analysis of core promoter activity of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 in ESCs and 3T3 cells. Biological-triplicate data (n =3 extracts) are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

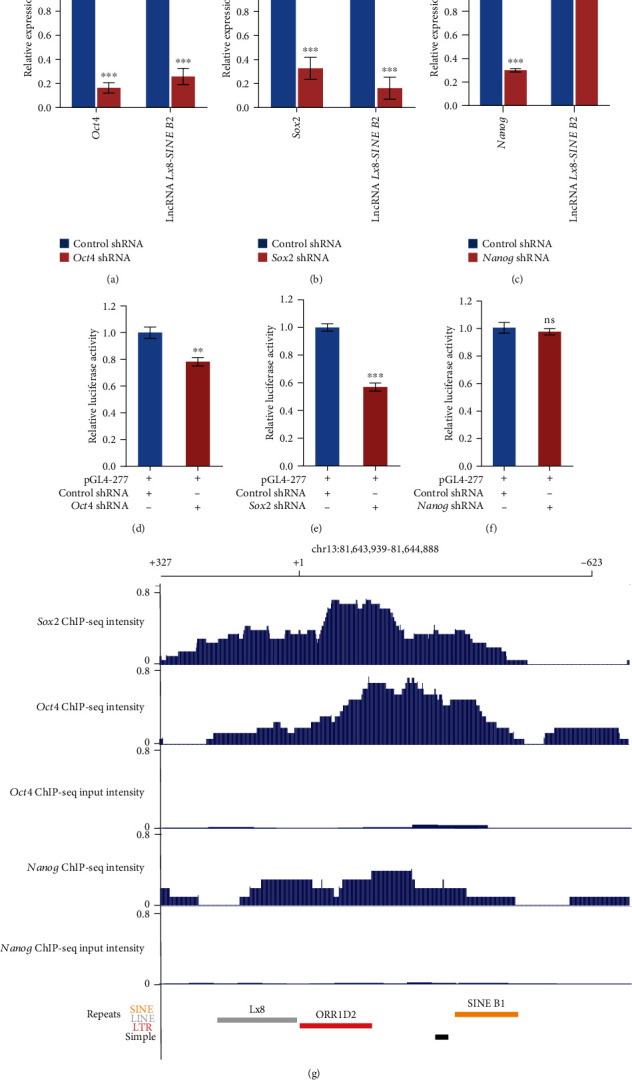

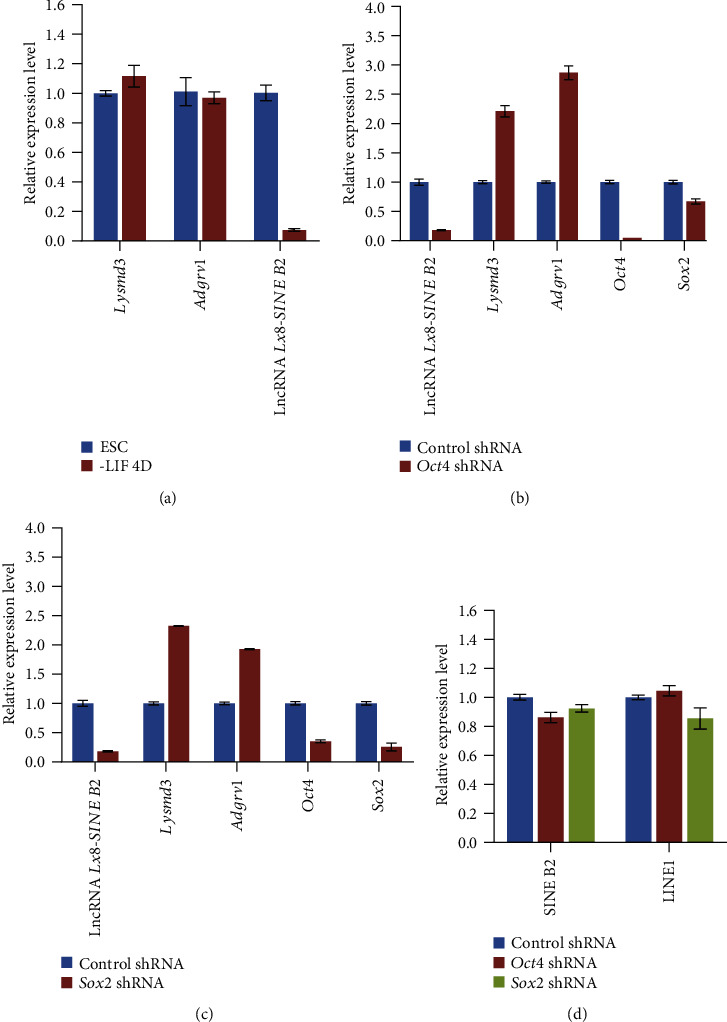

3.4. Transcriptional Regulation of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 by Oct4 and Sox2

To identify which transcription factor activates lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2, we depleted three core pluripotency transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog) (Figures 4(a)–4(c)). Depletion of Oct4 or Sox2, but not Nanog, strongly suppressed lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 expression (Figures 4(a)–4(c)). We also examined the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 after the depletion of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (Figures 4(a)–4(c)). However, depletion of either Sox2 or Oct4, but not Nanog, affected the promoter activity of ORR1D2 (Figures 4(d)–4(f)). Sox2 depletion imposed stronger inhibition on ORR1D2 than Oct4 and Nanog (Figures 4(d)–4(f)). Furthermore, we examined the binding of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog on the promoter of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. Consistent with results from luciferase assay, only Oct4 and Sox2 bound to the promoter according to our analysis of published ChIP-seq data (Figure 4(g)). These results suggest that Sox2 and Oct4 directly bind to ORR1D2 to activate Lx8-SINE B2 in ESCs (Figure 4(g)).

Figure 4.

Oct4 and Sox2 drive the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2. (a–c) qPCR analysis of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 expression after depletion of core transcription factors Oct4 (a), Sox2 (b), and Nanog (c) in ESCs. The data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. ns, non-significant; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001 according to two-sided Student's t-test. Biological-triplicate data (n = 3 dishes). (d–f) Luciferase assay analysis of core promoter activity of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 after depletion of core transcription factors Oct4 (d), Sox2 (e), and Nanog (f) in ESCs. Biological-triplicate data (n = 3 extracts) are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (g) Binding profile of Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog on the promoter region of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 according to published data as described in methods. Input was included as a control.

To exclude the possibility that Oct4 and Sox2 activate neighboring genes of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 together with it, we examined the expression of Lysmd3 and Adgrv1 during ESC differentiation. Different from lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2, both Lysmd3 and Adgrv1 were unaffected by LIF withdrawal (Figure 5(a)). Furthermore, the expression of Lysmd3 and Adgrv1 were activated by depletion of Oct4 or Sox2, suggesting they are regulated differently from Lx8-SINE B2 (Figures 5(b) and 5(c)). Moreover, the expression of LINE1 and SINE B2 were not affected by Oct4 or Sox2 depletion (Figure 5(d)), confirming the specificity of Oct4 and Sox2 in activating the expression of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2.

Figure 5.

Expression of neighboring genes of Lx8-SINE B2. (a) qPCR analysis of neighboring genes (Adgrv1 and Lysmd3) of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 in ESCs cultured with or without LIF; (b, c) RT-qPCR analysis of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2, Adgrv1, Lysmd3 and pluripotent genes (Oct4 and Sox2) expression after depletion of Oct4 (b) or Sox2 (c) in E14 ESCs. The data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological replicates. (d) Expression of LINE1 and SINE B2 after depletion of Oct4 or Sox2.

4. Discussion

In summary, we identified a novel pluripotency marker lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2, whose expression is driven by the binding of Oct4 and Sox2 on ORR1D2. Oct4 and Sox2 are the core pluripotency regulators in ESCs [18, 19]. Oct4 and Sox2 can drive the expression of lncRNAs in cancer cells and ESCs [20–22]. The binding profiles of OCT4 are different in human and mouse ESCs [23], which can be explained by its binding differences on species-specific TEs [23]. Here, we found that Oct4 and Sox2 targeted mouse TE ORR1D2 to drive ESC-specific lncRNA expression (Figure 4), further supporting the important role of TEs in driving the expression of species-specific lncRNAs. There are many pluripotency markers; however, we provide Lx8-SINE B2 as an additional novel marker of pluripotency. It lies at the downstream of key pluripotency genes Oct4 and Sox2 (Figure 4). It composes of TEs and is distinct from traditional markers of pluripotency. In comparison to other ESC markers, Lx8-SINE B2 is unique as an ORR1D2-driven pluripotency marker, which demonstrates that transposable elements can function as cell type-specific lncRNA and promoter, similarly to protein-coding genes. Finally, its depletion is associated with the downregulation of Myc in ESCs [17]; therefore, Lx8-SINE B2 expression also reflects Myc expression status of ESCs. Myc represses primitive endoderm differentiation [24]. Myc also maintains ESC pluripotency and self-renewal [25]. Therefore, we speculate that the depletion of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 may cause a phenotype similar to that of Myc downregulation.

Our study demonstrates that different types of TEs combine to form lncRNA and drive lncRNA expression (Figures 2 and 3), implicating TEs as important components of lncRNA. TEs in lncRNAs work as an important RNA domain [26, 27]. TEs within lncRNAs regulate the tissue-specific expression of lncRNAs [4, 28]. In human, lncRNAs containing HERVH are specifically expressed in human ESCs [3, 4, 7]. TEs within lncRNAs also contribute to their functions. For example, SINE B2 in antisense lncRNA of Uchl1 interacts with Uchl1 mRNA and promotes the translation of Uchl1 through enhancing the association of mRNA with polysome [29]. These studies demonstrate that TEs are critical to the expression and function of lncRNAs. Given that lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 is composed of TE Lx8 and SINE B2, it will be interesting to investigate whether ORR1D2 drive the expression of other lncRNAs and the function of Lx8 and SINE B2 within lncRNAs in the future study.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we mapped the full-length sequence of lncRNA Lx8-SINE B2 and found it as an ESC-specific lncRNA. We also found that it was driven by ORR1D2 which was bound by Sox2 and Oct4 to drive its transcription. These findings support TEs as important compositions and promoter of lncRNA.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871488, 32070858), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0107000), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (63151113, 63161150). We thank Ruiqing Chen for his technical assistance.

Data Availability

Published ChIP data analyzed by Cistrome [30] in this study are GSE54103 for Sox2 [31], GSE78073 for Oct4 [32], and GSE56312 for Nanog [33].

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that there is no conflict of interest present for this study.

Authors' Contributions

X. Lu conceived and designed the study. F.C., M.Z., and X. Li performed most experiments. X.F. and H.S. did bioinformatics analysis. F.C., M.Z., and X. Lu wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Weiss R. A. Exchange of genetic sequences between viruses and hosts. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2017;407:1–29. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell K. A., Burns K. H. Mobilizing diversity: transposable element insertions in genetic variation and disease. Mobile DNA. 2010;1(1):p. 21. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X., Sachs F., Ramsay L. A., et al. The retrovirus HERVH is a long noncoding RNA required for human embryonic stem cell identity. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2014;21(4):423–425. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley D., Rinn J. Transposable elements reveal a stem cell-specific class of long noncoding RNAs. Genome Biology. 2012;13(11):p. R107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-11-r107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd C. D., Deniz Ö., Taylor D., Branco M. R. Functional evaluation of transposable elements as enhancers in mouse embryonic and trophoblast stem cells. eLife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.44344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao B., Fu S., Lyu C., Gontarz P., Wang T., Zhang B. Tissue-specific usage of transposable element-derived promoters in mouse development. Genome Biology. 2020;21(1):p. 255. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapusta A., Kronenberg Z., Lynch V. J., et al. Transposable elements are major contributors to the origin, diversification, and regulation of vertebrate long noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9(4, article e1003470) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loewer S., Cabili M. N., Guttman M., et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(12):1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J., Zhang A., Ho T. T., et al. Linc-RoR promotes c-Myc expression through hnRNP I and AUF1. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(7):3059–3069. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Xu Z., Jiang J., et al. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Developmental Cell. 2013;25(1):69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durruthy-Durruthy J., Sebastiano V., Wossidlo M., et al. The primate-specific noncoding RNA HPAT5 regulates pluripotency during human preimplantation development and nuclear reprogramming. Nature Genetics. 2016;48(1):44–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J., Fu X., Zhang M., et al. Transposable elements are regulated by context-specific patterns of chromatin marks in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature Communications. 2019;10(1):p. 34. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08006-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Xie G., Singh M., et al. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive- like stem cells. Nature. 2014;516(7531):405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature13804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J., Wang L., Feng G., et al. Asymmetric expression of LincGET biases cell fate in two-cell mouse embryos. Cell. 2018;175(7):1887–1901.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.039. e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu E., Shen J., Dong Z., et al. Histone demethylase Kdm2a regulates germ cell genes and endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Epigenomics. 2019;11(7):751–766. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen F., Zhang W., Xie D., Gao T., Dong Z., Lu X. Histone chaperone FACT represses retrotransposon MERVL and MERVL-derived cryptic promoters. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020;48(18):10211–10225. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttman M., Donaghey J., Carey B. W., et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477(7364):295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyer L. A., Lee T. I., Cole M. F., et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122(6):947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X., Xu H., Yuan P., et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(6):1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jen J., Tang Y. A., Lu Y. H., Lin C. C., Lai W. W., Wang Y. C. Oct4 transcriptionally regulates the expression of long non-coding RNAs NEAT1 and MALAT1 to promote lung cancer progression. Molecular Cancer. 2017;16(1):p. 104. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0674-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheik Mohamed J., Gaughwin P. M., Lim B., Robson P., Lipovich L. Conserved long noncoding RNAs transcriptionally regulated by Oct4 and Nanog modulate pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. RNA. 2010;16(2):324–337. doi: 10.1261/rna.1441510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao W., Qi C. Q., Feng M. G., Yang P., Liu L., Sun S. H. SOX2-induced upregulation of lncRNA LINC01561 promotes non-small-cell lung carcinoma progression by sponging miR-760 to modulate SHCBP1 expression. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2020;235(10):6684–6696. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunarso G., Chia N. Y., Jeyakani J., et al. Transposable elements have rewired the core regulatory network of human embryonic stem cells. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(7):631–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith K. N., Singh A. M., Dalton S. Myc represses primitive endoderm differentiation in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(3):343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varlakhanova N. V., Cotterman R. F., deVries W. N., et al. Myc maintains embryonic stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 2010;80(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fort V., Khelifi G., Hussein S. M. I. Long non-coding RNAs and transposable elements: A functional relationship. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2021;1868(1, article 118837) doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchins A. P., Pei D. Transposable elements at the center of the crossroads between embryogenesis, embryonic stem cells, reprogramming, and long non-coding RNAs. Science Bulletin. 2015;60(20):1722–1733. doi: 10.1007/s11434-015-0905-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chishima T., Iwakiri J., Hamada M. Identification of transposable elements contributing to tissue-specific expression of long non-coding RNAs. Genes. 2018;9(1) doi: 10.3390/genes9010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrieri C., Cimatti L., Biagioli M., et al. Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nature. 2012;491(7424):454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature11508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu T., Ortiz J. A., Taing L., et al. Cistrome: an integrative platform for transcriptional regulation studies. Genome Biology. 2011;12(8):p. R83. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J., Zhang Z., Li L., et al. Single-molecule dynamics of enhanceosome assembly in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2014;156(6):1274–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin J., Kim T. W., Kim H., et al. Aurkb/PP1-mediated resetting of Oct4 during the cell cycle determines the identity of embryonic stem cells. eLife. 2016;5, article e10877 doi: 10.7554/eLife.10877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galonska C., Ziller M. J., Karnik R., Meissner A. Ground state conditions induce rapid reorganization of core pluripotency factor binding before global epigenetic reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(4):462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Published ChIP data analyzed by Cistrome [30] in this study are GSE54103 for Sox2 [31], GSE78073 for Oct4 [32], and GSE56312 for Nanog [33].