Dear Editor,

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are facing a threatening environment while their health is at risk [1]. In addition, the non-invasive ventilation procedure causes stress and anxiety which reduce cooperation [2]. We developed an intervention containing hypnotic suggestions to improve patients’ well-being during non-invasive ventilation in the ICU [3–5]. The aim of this study was to test the feasibility, safety, and acceptance of this intervention. Our main hypothesis was that subjective ratings will be improved after the intervention.

We used a pre–post-design with subjective ratings of patients before and after the intervention. During the intervention, patients received non-invasive ventilation and their physiological responses were measured by standard vital sign recordings. The protocol of this study was published previously [4]. Our study was approved by the ethics committee of the Jena University Hospital in Germany (#2019–1463; July 15, 2019).

We included patients who were afraid of non-invasive ventilation due to previous experience. Exclusion criteria were a Glasgow Coma Scale value below 14, delirium, lack of orientation, being deaf or not fluent in German language. All patients signed an informed consent statement.

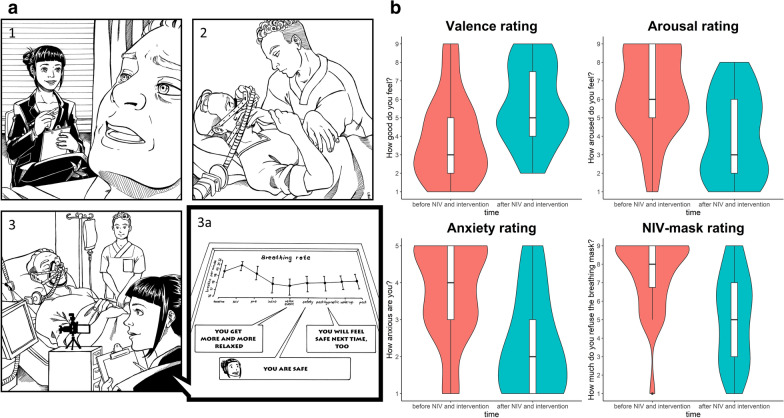

Two female psychology master students trained by B. S. performed the intervention. Before and after the non-invasive ventilation session, patients rated their subjective valence, arousal and anxiety as well as their subjective breathing mask comfort. To start non-invasive ventilation, a member of the clinical staff put the breathing mask on the patients’ face. The trained psychologist sat down next to the patient and explained the following procedure. The intervention was applied via a standardized verbatim text available as supplementary material. The approximate duration of each experimental event is reported in the supplementary material. In total, the intervention lasted about 15 min Fig. 1a.

Fig. 1.

a Main events of the experiment: 1. Subjective ratings before NIV, 2. NIV, 3. Hypnotic suggestions during NIV while physiological parameters are recorded (3a). b Violin plots of subjective ratings before and after NIV and intervention. Violin plots contain boxplots around the median and colored areas indicating the probability density of the rating scores

We obtained data of 31 patients (mean age 63.9 years [SD 11], 14 female and 17 male). Patients rated their subjective valence as significantly more positive, d = 0.69 (95% CI 0.3–1.09), their subjective arousal as significantly lower, d = 0.67 (95% CI 0.28–1.07) and their anxiety as significantly lower, d = 0.85 (95% CI 0.44–1.28) after the intervention compared to before the intervention. Patients rated the breathing mask as significantly more comfortable after the intervention compared to before the intervention, d = 1.08 (95% CI 0.62–1.57) Fig. 1b. Physiological responses show that breathing rate and heart rate decreased during the intervention, shown by significant main effects of the event for breathing rate, F(8,224) = 7.4, p < 0.001, η2G = 0.21 (95% CI 0.1–0.28) and heart rate, F(8,224) = 5.7, p < 0.001, η2G = 0.17 (95% CI 0.07–0.24). Detailed results are available as supplementary material.

This study shows the feasibility, safety, and acceptance of hypnotic suggestions to increase well-being during non-invasive ventilation in the ICU. Future randomized-controlled studies should test the efficacy of the intervention against suitable control groups including a group receiving non-invasive ventilation without hypnotic suggestions. We conclude that hypnotic suggestions can improve well-being during challenging medical procedures like non-invasive ventilation that are also applied in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Teresa Deffner and Jenny Rosendahl contributed equally.

References

- 1.Karnatovskaia LV, Philbrick KL, Parker AM, Needham DM. Early psychological therapy in critical illness. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37:136–142. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nava S, Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Lancet. 2009;374:250–259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt B, Holroyd CB. Hypnotic suggestions of safety reduce neuronal signals of delay discounting. Sci Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81572-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt B, Deffner T, Rosendahl J. Feeling safe during intensive care: protocol of a pilot study on therapeutic suggestions of safety under hypnosis in patients with non-invasive ventilation. OBM Integr Complem Med. 2020;5(2):8. doi: 10.21926/obm.icm.2002025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt B, Hoffmann E, Rasch B. Feel safe and money is less important hypnotic suggestions of safety decrease brain responses to monetary rewards in a risk game. Cerebral Cortex Commun. 2020 doi: 10.1093/texcom/tgaa050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.