Abstract

COVID-19, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), affects people of all ages. The virus can cause multiple systemic infections, principally in the respiratory tract, as well as microvascular damage. Ocular manifestations of COVID-19 are uncommon in adults and children. We describe ophthalmic manifestations in newborns detected by slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, and fluorescein angiography. All patients showed edema and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis; fundus examinations revealed cotton wool spots and vitreous hemorrhage, and microvascular damage manifested as patchy choroidal filling, peripapillary hyperfluorescence, delayed retinal filling and venous laminar flow, and boxcarring on fluorescein angiography.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with ophthalmological changes at all levels1; ocular external diseases, such as conjunctivitis, and intraocular changes, including inflammation and microvascular alterations.2 , 3 The virus affects people of all ages and may be encountered as well in pregnant women and newborns.4 , 5

Subjects and Methods

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of Hospital Materno Perinatal Monica Pretelini. During the hospital reconversion project carried out by the federal health authorities in Mexico, the Hospital Materno Perinatal Monica Pretelini was designated as the regional reference center for pregnant-puerperal women and newborns with suspected COVID-19 infection. On admission, both mothers and newborns were tested for SARS-CoV2. Newborns with positive RT-PCR tests (from nasopharyngeal swabs) for SARS-CoV-2, who were isolated in a neonatal intensive care unit designed for this purpose, were included in the present cross-sectional study.

All subjects received complete ophthalmic exploration, including portable slit-lamp examination, fundus examination, color fundus photography, and red-free imaging and fluorescein angiography using a contact wide-angle imaging system (RetCam 3, Natus).

Results

Fifteen newborns (8 females [53%]) were enrolled. The mean gestational age was 35.2 weeks (range, 30-40), and the average birth weight was 2238.7 g (range, 1140–4350 g). Ten mothers were positive for SARS-CoV-2. See Table 1 .

Table 1.

Ophthalmic manifestations in newborns (N = 15)

| Study parameter | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Systemic findings | |

| Fever | 13 (86.6) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 7 (46.6) |

| Cardiac arrest | 3 (20) |

| Seizures | 2 (13.3) |

| Tachypnea | 13 (86.6) |

| Sepsis | 5 (33.3) |

| Fundus findings | |

| Normal | 7 (46.6) |

| Oxygen-induced retinopathy | 2 (13.3) |

| ROP | 3 (20) |

| Cotton wool spots | 2 (13.3) |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 1 (6.6) |

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection | |

| Positive | 10 (66.6) |

| Negative | 5 (33.3) |

| Corneal and external findings | |

| Periorbital edema | 15 (100) |

| Hemorrhagic conjunctivitis | 11 (73.3) |

| Corneal edema | 6 (40) |

| Hyaline secretion | 15 (100) |

| Rubeosis | 1 (6.6) |

| Angiography findings | |

| ROP findings | 3 (20) |

| Oxygen-induced findings | 3 (33.3) |

| Patchy choroidal filling | 3 (20) |

| Peripapillary hyperfluorescence | 3 (20) |

| Blockeage hypofluorescence in vitreous hemorrhage | 1 (6.6) |

| Boxcarring | 2 (13.3) |

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

The systemic findings were as follows. Nine newborns (60%) had low Apgar scores (<7 at 5 minutes), most (87%) had a fever, and 13 (87%) had tachypnea. Neonatal jaundice was present in 6 newborns (40%) and sepsis in 5 (33%). Four had cardiovascular alterations, and 9 had respiratory alterations. Seven newborns required a blood transfusion for anemia, 2 had seizures, and 3 had a cardiac arrest with successful resuscitation. Of the 15 newborns, 7 (47%) required mechanical ventilation, and the other 8 (53%) received supplemental oxygen.

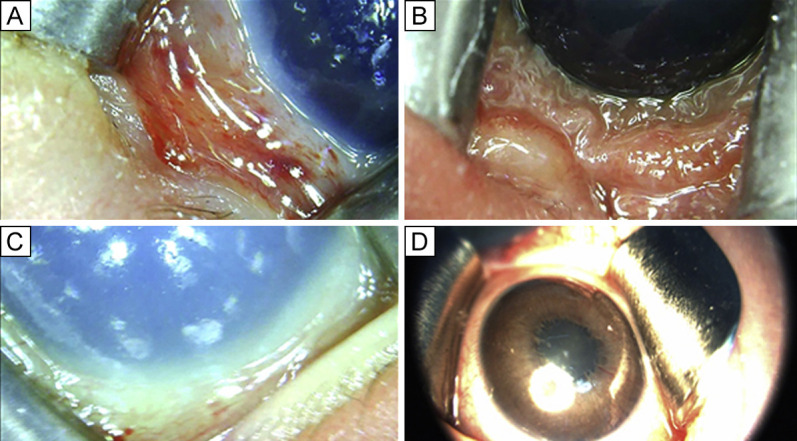

The most frequent periorbital finding was edema, present in all 15 newborns. Chemosis and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis were present in 11 newborns (73%), and 8 (53%) had ciliary injection. All 15 newborns had hyaline secretion. The most frequent corneal and anterior segment finding was corneal edema, present in 6 newborns (40%). One full-term newborn had rubeosis and posterior synechiae. See Figure 1 .

Fig 1.

External ophthalmic manifestations of SARS-CoV2 in newborns. A, Hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. B, Chemosis. C, Corneal edema and mild hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. D, Rubosis iridis and posterior synechiae.

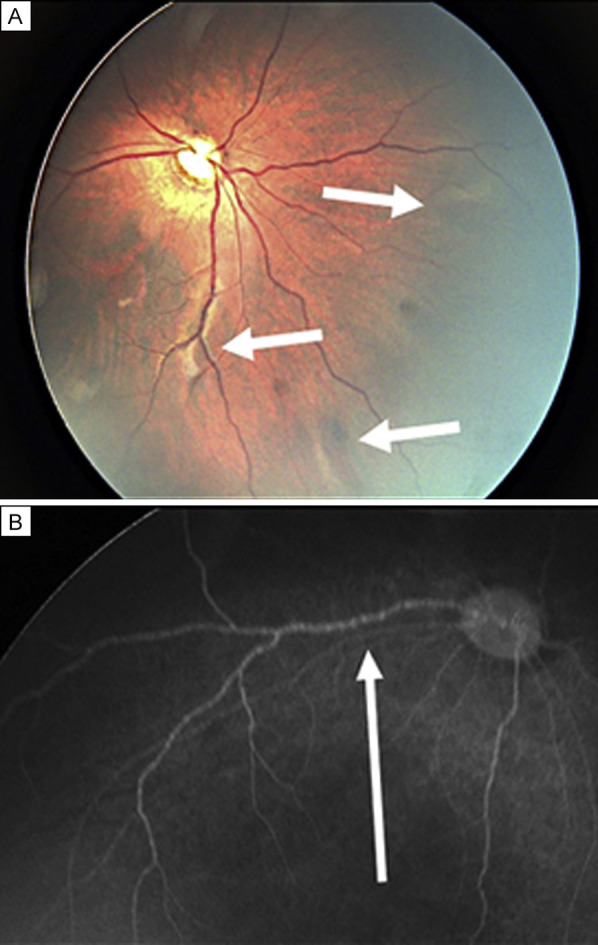

Fundus examination was normal in 7 newborns (47%). Of the remaining 8 newborns, 2 (13%) were diagnosed with oxygen-induced retinopathy, 3 (20%) had retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), 2 (13%) had subtle cotton wool spots, and 1 (7%), born at full term, had vitreous hemorrhage.

Fluorescein angiography was performed in all patients. Of the 15, 3 (20%) had changes compatible with ROP, 2 (13%) had oxygen-induced retinopathy, 3 (20%) were reported to have patchy choroidal filling, and 3 (20%) showed peripapillary hyperfluorescence. The remaining 2 newborns (13%) had delayed retinal filling, venous laminar flow, and boxcarring. See Figure 2 and Video 1.

Fig 2.

Fundus manifestations of SARS-CoV2 in Newborns. A, Cotton wool spots. B, Retinal venous laminar flow and boxcarring sign on fluorescein angiography.

Discussion

Several reports describe the ocular involvement of SARS-CoV-2. Wu and colleagues,6 Zhou and colleagues,7 and Seah and colleagues8 describe ophthalmological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 in adult patients, including conjunctivitis, red-eye, tearing, blurring vision in 1 of 3 patients.

Valente and colleagues4 describe ocular involvement in children, the symptoms were mild, those were present in 15%, mainly viral conjunctivitis. Invernizzini and colleagues9 reported hemorrhages (9.25%), cotton wools spots (7.4%), dilated veins (27.7%), tortuous vessels (12.9%) in their patient cohort.

All newborns in our study had ocular manifestations, the most common being periorbital edema and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis; 53% had retinal findings. The most frequent presentation at this age could be explained by the overlap of COVID-19 and comorbidities associated with prematurity.

This is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive report of ophthalmic findings in newborn babies possibly associated with COVID-19 infection in humans. As it is a new virus, all ocular manifestations in newborns are unknown, and the higher frequency of findings may be due to the multiple comorbidities and weakness in the patients. The mechanism of ocular injury in this study is unknown and may be related to prematurity, hemodynamic compromise, mechanical ventilation, or SARS-CoV2. We are following all the cases reported here for long-term complications.

Literature Search

PubMed and the MEDLINE databases were searched, without date restriction, for results in English or Spanish, using the following terms: COVID19, SARS-CoV-2, COVID AND newborns, COVID AND ophthalmic manifestation. Clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and systematic evaluations in peer-reviewed journals were included.

Supplementary Data

Retina boxcarring in a newborn patient with COVID-19.

References

- 1.Seah I., Agrawal R. Can the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affect the eyes? A review of coronaviruses and ocular implications in humans and animals. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:391–395. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1738501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amesty M.A., Alió Del Barrio J.L., Alió J.L. 2020. COVID-19 disease and ophthalmology: an update Ophthalmol Ther; pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valente P., Iarossi G., Federici M., et al. Ocular manifestations and viral shedding in tears of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a preliminary report. J AAPOS. 2020;24:212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiSciullo A., Mokhtari N., Fries M. Review of maternal COVID-19 infection: considerations for the pediatric ophthalmologist. J AAPOS. 2020;24:209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu P., Duan F., Luo C., et al. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:575–578. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou S., Wang Y., Zhu T., Xia L. CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in 62 patients in Wuhan, China. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1287–1294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seah I.Y.J., Anderson D.E., Kang A.E.Z., et al. Assessing viral shedding and infectivity of tears in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:977–979. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Invernizzi A., Torre A., Parrulli S., et al. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19: results from the SERPICO-19 study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;27:100550. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Retina boxcarring in a newborn patient with COVID-19.