Abstract

High systolic blood pressure (BP) is the single leading modifiable risk factor for death worldwide. Accurate BP measurement is the cornerstone for screening, diagnosis, and management of hypertension. Inaccurate BP measurement is a leading patient safety challenge. A recent World Health Organization report has outlined the technical specifications for automated noninvasive clinical BP measurement with cuff. The report is applicable to ambulatory, home, and office devices used for clinical purposes. The report recommends that for routine clinical purposes, (1) automated devices be used, (2) an upper arm cuff be used, and (3) that only automated devices that have passed accepted international accuracy standards (eg, the International Organization for Standardization 81060-2; 2018 protocol) be used. Accurate measurement also depends on standardized patient preparation and measurement technique and a quiet, comfortable setting. The World Health Organization report provides steps for governments, manufacturers, health care providers, and their organizations that need to be taken to implement the report recommendations and to ensure accurate BP measurement for clinical purposes. Although, health and scientific organizations have had similar recommendations for many years, the World Health Organization as the leading governmental health organization globally provides a potentially synergistic nongovernment government opportunity to enhance the accuracy of clinical BP assessment.

Keywords: blood pressure, hypertension, risk factors, sphygmomanometers, systole

High systolic blood pressure (BP) is the single leading modifiable risk factor for death worldwide, with 10.8 million deaths per year attributable to raised BP in 2019.1 Globally, an estimated 1.39 billion people had hypertension in 2010, and 75% of the burden (1.04 billion) was in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).2 In high-income countries, the age-adjusted prevalence of raised systolic BP has been decreasing slightly, but it has been increasing in LMIC.2 Nevertheless, with increasing life expectancy and aging, the absolute number of people with raised BP and resultant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is increasing globally. There are major deficiencies with respect to awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of high BP, and these problems persist across countries of all income levels, highlighting the urgency for widespread population-level interventions.2–5

Accurate BP measurement is the cornerstone for screening, diagnosis, and management of hypertension.3,5,6 It is widely recognized that if the presence of high BP can be correctly identified with appropriate use of accurate BP devices and adherence to BP measurement protocols, the risk of future cardiovascular events can be reduced significantly with dietary and lifestyle interventions and antihypertensive medications.3,7

The World Hypertension League, STRIDE BP, Resolve to Save Lives, Accuracy in Measurement of BP, and the Lancet Commission on Hypertension Group have identified the need for better-quality BP measurements, obtained using certified BP monitors that have been validated for accuracy.8–13

BP measurement has been cited as one of the most important tests in clinical medicine.14 Ensuring the accuracy of this measurement is of paramount importance, as inaccurate BP measurement can result in diagnostic and management errors, contributing to one of the leading patient safety challenges in contemporary clinical practice. Both overestimation and underestimation of BP result in missed opportunities to apply resources to those individuals who will benefit most from diagnosis and treatment.

Most commonly, inaccurate BP measurement results in an overestimation of BP, which can lead to almost twice as many patients being misclassified as having a higher reading than they actually do.15,16 When BP is overestimated, patients may be exposed unnecessarily to pharmacological agents to lower BP placing them at risk for hypotensive symptoms, medication side effects, financial burden, and the stigma of living with a chronic medical condition. Overestimation of BP also impacts health systems by diverting resources to repeat testing, treatment initiation, ancillary medical services such as laboratory analyses, and follow-up visits to the health center. The 2020 “WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measuring Devices With Cuff” (World Health Organization [WHO] BP device report) recommends that BP should be monitored at home to confirm a hypertension diagnosis due to white-coat hypertension.

If inaccurate measurement results in an underestimation of BP, there is a missed opportunity to prevent avoidable cardiovascular events. When inaccuracies are systematically amplified in the health system context, misdiagnosis and misclassification of many millions of people at the population level can occur.16,17 Inaccurate BP devices are of special concern as the errors introduced by such devices will consistently impact all those measured and can misclassify people as having or not having hypertension on a grand scale. As an example, a consistent inaccuracy of 5/2.7 mm Hg can change the estimated hypertension prevalence by 30%.18

BP-Measuring Devices

According to the WHO, high-quality health technologies, such as accuracy-validated BP devices, are indispensable for effective universal health care delivery.19 The Figure from the WHO report shows some of the disadvantages and advantages of the different types of noninvasive BP devices. Other critical components of accurate BP assessment include the use of appropriate equipment (eg, correct cuff, intact tubing), proper patient preparation (eg, no talking, resting with empty bladder, and no exercise nor tobacco/caffeine use in prior 30 minutes), a quiet comfortable measurement setting, and consistent use of a recommended standardized measurement technique (proper position [eg, seated, feet flat on the floor, back supported, arm supported at the level of the heart]).20,21 Accurate BP measurement is essential to identify and to guide treatment decisions, including when to start medication and when to adjust the dose. Lack of access to accurate, affordable BP devices is a significant barrier to proper medical care, particularly in low-resource settings.22

Figure.

Subcategories of noninvasive blood pressure–measuring devices (BPMDs) and their advantages and disadvantages. BP indicates blood pressure; and WHO, World Health Organization. *Adapted from the World Health Organization.6 Copyright © 2020, World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

During recent years, there has been a slow evolution in clinical BP measurement. Mercury manometers are being phased out because of environmental concerns related to mercury. The need for frequent calibration to maintain accuracy and the increased risk for observer error and inaccurate BP measurements with aneroid manual BP devices has led the WHO to recommend accuracy-validated automatic devices for adult BP measurements since 2005.22 Accuracy-validated automated devices may produce more accurate and consistent measurements on a global scale. While automated devices reduce human error from many sources (eg, visualizing the BP reading, listening for the appropriate Korotkoff sound, remembering and recording the systolic and diastolic numbers), few have undergone rigorous validation testing according to standardized protocols10,12,23–25 resulting in many of these newer devices providing inaccurate readings. Therefore, these automated devices, including automated office, home, wrist band, and ambulatory BP measurement devices, have the potential to yield inaccurate readings, particularly if they have not passed rigorous validation testing. The historical lack of a clear standardized universal validation protocol and poor guidance regarding ideal product characteristics of automated BP-measuring devices for various settings have contributed to the wide availability of many home and clinical-use BP devices of poor or unknown accuracy. In most geographic regions, nonvalidated home BP devices dominate the online marketplace.25

Rationale for Development of Technical Specifications for BP-Measuring Devices

Multiple nongovernmental organizations have identified improving the quality of BP measurements by using BP devices that have been validated for accuracy as a key action needed to address the worldwide burden of high BP.8–13 These organizations highlight the urgent need for an endorsed, global validation protocol to guide device accuracy testing and for restricted/limited marketing of unvalidated BP measurement devices. Other key recommendations include developing validation standards to address the unique aspects of new BP technologies (such as cuffless BP estimating devices) and providing online resources to identify accuracy-validated devices that are accessible to both consumers and health professionals.26

Concerns around the lack of accurate, good-quality BP devices, especially in LMICs, were expressed by key stakeholders at a workshop on BP measurement during the Fourth WHO Global Forum on Medical Devices hosted by the Government of India in 2018.27

WHO undertook a technical consultation and expert review in June 2019 with invited members who had relevant expertise across diverse skills, namely scientific, technical, advocacy, and implementation science, and who represented organizational sectors such as government and nongovernment, as well as professional societies from different world regions.6 The objective of the consultation and technical review was to outline the key performance characteristics and technical specifications for noninvasive BP measurement devices that are essential for accurate BP measurement and the successful diagnosis and management of hypertension.

WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Noninvasive BP-Measuring Devices With Cuff

To accomplish these aims and provide a comprehensive overview, WHO developed technical specifications for automated noninvasive BP-measuring devices with cuffs.6 The report is applicable to ambulatory, home, and office devices used for clinical purposes. This document defines the characteristics of accurate BP devices, describes the regulatory requirements and standards, and details how and when to perform calibration and maintenance for various BP measurement devices. These specifications also provide guidance on procurement and decommissioning of devices including decontamination of mercury when applicable. It further addresses the procedures for accurate measurement of BP including training of personnel. The report recommends only upper arm cuff devices for routine clinical use.

In this article, we briefly outline the “WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measuring Devices With Cuff” and provide the implementation recommendations for governments, manufacturers, health care professionals, and organizations, as well as global and national implementing partners.6 We also focus on the need for strengthening the health care workforce capacity in standardized BP measurement practices. We envisage that these significant steps will help and support effective hypertension control and decrease the worldwide burden of high BP, saving millions of lives.

Recommendations on BP Measurement Devices

The technical expert group supporting the report reviewed the evidence for the accuracy and use of aneroid, semiautomatic, and automatic BP-measuring devices and provided the following recommendations.

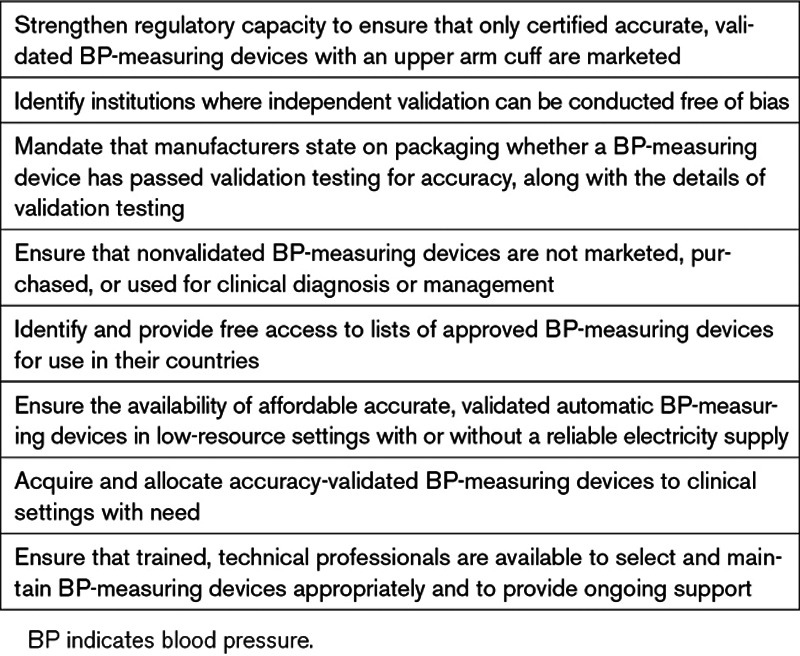

Recommendations for Governments

The Table summarizes the main recommendations from the expert group to governments. To increase access to accurate BP measurement and monitoring, governments are encouraged to not only strengthen their regulatory capacity to ensure that only certified accurate, validated BP-measuring devices are marketed but also to identify institutions where independent validation can be conducted free of bias. Moreover, nonvalidated BP-measuring devices should not be marketed, purchased, and used for clinical diagnosis or management. Regulation of the online industry is especially important as consumers may unwittingly purchase nonvalidated BP devices, which may then be used in clinical management.25 Governments should enforce quality assurance by mandating that manufacturers state clearly on packaging whether their BP-measuring device has passed validation testing for accuracy. Moreover, governments should ensure that nonvalidated BP-measuring devices are not marketed, purchased, or used for clinical diagnosis or management.

Table.

Report Recommendations for Governments

Governments should identify and provide free access to lists of approved devices for use in their countries.

In addition, governments, health and scientific communities, and BP-measuring device manufacturers should ensure the availability of affordable accurate, validated automatic BP-measuring devices in low-resource settings with or without a reliable electricity supply. Some BP-measuring devices use alternate sources of energy or can operate with low energy requirements.

To ensure equitable access to reliable BP measurement using accuracy-validated BP-measuring devices, LMIC governments are encouraged to acquire and allocate accuracy-validated BP-measuring devices to clinical settings with need.

Governments are also urged to ensure that trained professionals, such as clinical engineering and other technical professionals, are available to appropriately select and maintain BP-measuring devices and provide ongoing support.

Recommendations for Manufacturers

Automated and semiautomated BP-measuring devices should undergo independent validation testing with the new universal international protocol (International Organization for Standardization 81060-2; 201828). Device labels should clearly indicate the protocol used to validate the device.

Manufacturers should specify the range of arm circumferences for which the device has been validated and should clearly mark the accompanying BP cuffs with the intended arm circumference range to help guide cuff size selection for each individual. Providing guidance on choosing the appropriate cuff size should be considered as part of the packaging instructions.

Recommendations for Health Care Professionals and Health Care Facilities

Accuracy-validated automatic BP-measuring devices with appropriately sized upper arm cuffs should be used in routine clinical and community screening for hypertension and home-based monitoring. A recent resource has been developed by the Accuracy in Measurement of BP collaborative to aid the selection of accuracy-validated devices.26

Certification courses and periodic training and retraining of health care professionals should be instituted to ensure accurate BP measurement. Competency-based evaluation of appropriate BP measurement should be undertaken regularly. Training should include patient preparation, cuff selection, and BP measurement technique. Checklists with the specific steps for accurate BP measurement should be provided in all settings where BP measurement is routinely undertaken. To minimize additional training for manual BP measurements, accuracy-validated automated noninvasive BP-measuring devices should be used. An international collaboration led by the Pan American Health Organization and World Hypertension League recently developed a brief free certification program for assessing BP with an accuracy-validated automated device.29,30 In addition, the Johns Hopkins University partnered with Resolve to Save Lives to produce a Global Hypertension Course, which includes instruction on proper BP measurement and hypertension diagnosis.31

Health care facilities in which manual BP-measuring devices containing mercury cannot yet be replaced by accuracy-validated electronic BP-measuring devices should inform their communities about the hazards of mercury and develop procedures for safe operation of the devices, search for ways to replace them with nonmercury ones, preferably automated, accuracy-validated BP-measuring devices, and undertake decommissioning as per standard protocols.

Recommendations for Development Partners and Implementation Agencies

WHO recognizes the pivotal role of affordable high-quality health technologies. As such, accuracy-validated BP devices are indispensable for effective universal health care delivery.32 There is an urgent need to prioritize accurate BP measurement to improve the diagnosis and treatment of high BP.1 Improving access to and availability of both accuracy-validated BP measurement devices and a health care workforce skilled in appropriate BP measurement is critical. Development partners and implementation agencies have an important role in supporting LMIC governments in building capacity for optimal health care delivery, which includes creating pathways for improved access to accuracy-validated BP-measuring devices.

Advocacy efforts of key decision-makers within governments and departments of health are critical for successful translation of these technical specifications and recommendations for implementation into actionable programmatic interventions. WHO urges stakeholders to leverage opportunities for improving access to reliable BP measurement and availability of accuracy-validated BP-measuring devices. This can be done globally through existing international programmes and resources, such as the WHO Programme on Cardiovascular Disease, through the national programmes of noncommunicable disease control, and by working in close partnership with key opinion leaders, local champions, and organizations supporting national governments in implementing noncommunicable disease control programmes.

Discussion

BP measurement is a fundamental medical test performed daily on many millions of people worldwide. Health professionals together with consumers should have confidence in BP measurements obtained by BP-measuring devices; accuracy of these devices is essential for appropriate BP assessment during screening, diagnosis, and management of hypertension.8–13 It is noteworthy that the HEARTS in the Americas program of the Pan American Health Organization held a meeting shortly following the release of the WHO report to examine how national governments could best implement the recommendations both in the short and long term. Several national government agencies were in the position to quickly introduce aligned device procurement policies and agreed to provide annual updates on progress. Cuba—one of the original HEARTS in the Americas Program—had already adopted many of the recommendations of the WHO report including a certification course for BP measurement and the production, testing, and use of accuracy-validated electronic BP devices. Resolve to Save Lives—an initiative of Vital Strategies that implements programs aimed at improving hypertension control—also has a policy for procurement of accuracy-validated, automatic BP devices and training in accurate BP measurement.33 These and other best practices demonstrate the feasibility of the recommendations at a population level.

Conclusions

While governments have developed national noncommunicable diseases control programmes and multisectoral action plans to address the burden of noncommunicable diseases, the lack of specific guidance such as technical specifications on BP measurement and selection of devices has historically limited the optimum implementation of such programmes. The “WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measuring Devices With Cuff” released in 2020 provides timely guidance for governments, manufacturers, health care professionals, and providers. International and national public health organizations should use the WHO report to advocate that governments provide automated, accuracy-validated BP devices and the skilled workforce needed to optimize hypertension screening, treatment, and control to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Valeria Montant for her support in the writing and revision of the “WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measuring Devices With Cuff” report.

Sources of Funding

The 2020 “WHO Technical Specifications for Automated Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Measuring Devices With Cuff” was supported financially by the World Health Organization and Resolve to Save Lives. O. John is a recipient of Australia University International Postgraduate Awards scholarship from University of New South Wales, Sydney. T.M. Brady received support from Resolve to Save Lives, which is funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Gates Philanthropy.

Disclosures

A.E. Schutte declares receiving speaker honoraria from Servier, Takeda, Omron, and Novartis. The other authors report no conflicts.

Footnotes

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BP

- blood pressure

- LMIC

- low- and middle-income country

- WHO

- World Health Organization

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 811.

Contributor Information

Oommen John, Email: ojohn@georgeinstitute.org.in.

Tammy M. Brady, Email: tbrady8@jhmi.edu.

Margret Farrell, Email: mfarrell@resolvetosavelives.org.

Cherian Varghese, Email: varghesec@who.int.

Adriana Velazquez Berumen, Email: velazquezberumena@who.int.

Laura A. Velez Ruiz Gaitan, Email: velezruizgaitanla@who.int.

Nicola Toffelmire, Email: toffelmiren@who.int.

Mohammad Ameel, Email: mohdameel@gmail.com.

Marc G. Jaffe, Email: marc.jaffe@kp.org.

Aletta E. Schutte, Email: a.schutte@unsw.edu.au.

Taskeen Khan, Email: khant@who.int.

Laura Patricia Lopez Meneses, Email: ing.lplm@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, et al. ; GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, Chen J, He J. global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell NRC, Schutte AE, Varghese CV, Ordunez P, Zhang XH, Khan T, Sharman JE, Whelton PK, Parati G, Weber MA, et al. São Paulo call to action for the prevention and control of high blood pressure: 2020. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:1744–1752. doi: 10.1111/jch.13741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Gupta R, Avezum A, Bahonar A, Chifamba J, Dagenais G, Diaz R, et al. ; PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) Study Investigators. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310:959–968. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.184182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen MH, Angell SY, Asma S, Boutouyrie P, Burger D, Chirinos JA, Damasceno A, Delles C, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Hering D, et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388:2665–2712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31134-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO technical specifications for automated non-invasive blood pressure measuring devices with cuff. 2020. World Health Organization; 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, Chalmers J, Rodgers A, Rahimi K. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell NR, Berbari AE, Cloutier L, Gelfer M, Kenerson JG, Khalsa TK, Lackland DT, Lemogoum D, Mangat BK, Mohan S, et al. Policy statement of the world hypertension league on noninvasive blood pressure measurement devices and blood pressure measurement in the clinical or community setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:320–322. doi: 10.1111/jch.12336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padwal R, Campbell NRC, Schutte AE, Olsen MH, Delles C, Etyang A, Cruickshank JK, Stergiou G, Rakotz MK, Wozniak G, et al. Optimizing observer performance of clinic blood pressure measurement: a position statement from the Lancet commission on hypertension group. J Hypertens. 2019;37:1737–1745. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharman JE, O’Brien E, Alpert B, Schutte AE, Delles C, Hecht Olsen M, Asmar R, Atkins N, Barbosa E, Calhoun D, et al. ; Lancet Commission on Hypertension Group. Lancet commission on hypertension group position statement on the global improvement of accuracy standards for devices that measure blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2020;38:21–29. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padwal R, Campbell NRC, Weber MA, Lackland D, Shimbo D, Zhang XH, Schutte AE, Rakotz M, Wozniak G, Townsend R, et al. ; Accuracy in Measurement of Blood Pressure Collaborative. The Accuracy in Measurement of Blood Pressure (AIM-BP) collaborative: background and rationale. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:1780–1783. doi: 10.1111/jch.13735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stergiou GS, O’Brien E, Myers M, Palatini P, Parati G, Kollias A, Birmpas D, Kyriakoulis K, Bountzona I, Stambolliu E, et al. ; STRIDE BP Scientific Advisory Board. STRIDE BP international initiative for accurate blood pressure measurement: systematic review of published validation studies of blood pressure measuring devices. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:1616–1622. doi: 10.1111/jch.13710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frieden TR, Varghese CV, Kishore SP, Campbell NRC, Moran AE, Padwal R, Jaffe MG, et al. Scaling up effective treatment of hypertension—A pathfinder for universal health coverage. J Clinical Hypertens. 2019;21:1442–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ; Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association Council on high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell NR, McKay DW. Accurate blood pressure measurement: why does it matter? CMAJ. 1999;161:277–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell NRC, Padwal R, Picone DS, Su H, Sharman JE. The impact of small to moderate inaccuracies in assessing blood pressure on hypertension prevalence and control rates. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:939–942. doi: 10.1111/jch.13915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones DW, Appel LJ, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ, Lenfant C. Measuring blood pressure accurately: new and persistent challenges. JAMA. 2003;289:1027–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joffres MR, Campbell NR, Manns B, Tu K. Estimate of the benefits of a population-based reduction in dietary sodium additives on hypertension and its related health care costs in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70780-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Assembly. Health technologies. Sixtieth World Health Assembly Resolution WHA60.29. 2007. World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Affordable Technology: Blood Pressure Measuring Devices for Low Resource Settings. 2005. World Health Organization; 92 4 159264 8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stergiou GS, Alpert B, Mieke S, Asmar R, Atkins N, Eckert S, Frick G, Friedman B, Graßl T, Ichikawa T, et al. A universal standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices: association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation/European Society of Hypertension/International Organization for Standardization (AAMI/ESH/ISO) collaboration statement. J Hypertension. 2018;37:459–466. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharman JE, Padwal R, Campbell NRC. Global marketing and sale of accurate cuff blood pressure measurement devices. Circulation. 2020;142:321–323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picone DS, Deshpande RA, Schultz MG, Fonseca R, Campbell NRC, Delles C, Hecht Olsen M, Schutte AE, Stergiou G, Padwal R, et al. Nonvalidated home blood pressure devices dominate the online marketplace in Australia: major implications for cardiovascular risk management. Hypertension. 2020;75:1593–1599. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picone DS, Padwal R, Campbell NRC, Boutouyrie P, Brady TM, Olsen MH, Delles C, Lombardi C, Mahmud A, Meng Y, et al. How to check whether a blood pressure monitor has been properly validated for accuracy. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;00:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Fourth WHO Global Forum on Medical Devices Report. 2019. World Health Organization; 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Organization for Standardization. Non-invasive sphygmomanometers - part 2: clinical investigation of intermittent automated measurement type. ANSI/AAMI/ISO 81060–2:2018.

- 29.Campbell NRC, Khalsa T, Ordunez P, Rodriguez Morales YA, Zhang XH, Parati G, Padwal R, Tsuyuki RT, Cloutier L, Sharman JE. Brief online certification course for measuring blood pressure with an automated blood pressure device. A free new resource to support World Hypertension Day Oct 17, 2020. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:1754–1756. doi: 10.1111/jch.14017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan American Health Organization. Virtual course on accurate automated blood pressure measurement. 2020. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.campusvirtualsp.org/en/course/virtual-course-accurate-automated-blood-pressure-measurement-2020

- 31.Global Hypertension at Hopkins. Courses: fundamentals for implementing a hypertension program in resource-constrained settings. 2020. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://globalhypertensionathopkins.org/courses

- 32.World Health Organization. Health technologies. Sixtieth World Health Assembly Resolution WHA60.29. 2007. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/WHA60_29.pdf?ua=1

- 33.Resolve to Save Lives. How to choose an automated blood pressure monitor: recommendations for low- and middle-income country settings. 2020. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://resolvetosavelives.org/assets/Resources/How-to-Choose-an-Automated-Blood-Pressure-Monitor.pdf