Abstract

Purpose

To explore facilitators and barriers for male partner follow through carrier screening (CS) after their female partners were identified as carriers, from both male and female perspectives.

Methods

Participants were either females identified as a carrier through CS (512 participants) or males who had CS (125 participants). Participants were recruited via e-mails with survey links. The survey explored factors surrounding decisions to pursue CS or not.

Results

Males who attended the females’ CS appointment were more likely to have CS (OR: 2.07). More male partners of females identified as carriers of severe or profound conditions pursued CS (82.0%) than male partners of females who were carriers for moderate conditions (50.0%). Logistic factors were more impactful for males who pursued CS. Females whose male partners did not test endorsed personal belief factors as most impactful, reporting the perceived low risk (75.0%) and his low concern for the specific condition (65.5%) were the top reasons their partners did not test.

Conclusion

Many factors impact how male partners appraise reproductive risk from CS and make decisions regarding their own screening. Advising that male partners attend CS appointments may increase the likelihood of follow through CS. Thorough and repeated risk counseling is indicated.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-020-02029-5.

Keywords: Carrier screening, Expanded carrier screening (ECS), Genetic counseling, Genetic screening, Reproductive genetics

Introduction

Carrier screening (CS) is a form of genetic screening which identifies couples at increased risk of having children affected with Mendelian conditions and strengthens their abilities to make informed reproductive decisions [1–3]. CS’s purpose is to identify carriers, unaffected individuals at risk to pass on disease-causing genetic variants to their offspring [1]. CS primarily focuses on identifying carriers of autosomal recessive conditions; there is a 25% risk for offspring to be affected if both the female and male partners are carriers for the same condition [1].

There are multiple approaches for evaluating couples with CS. CS can be performed simultaneously, for both partners at the same time, or sequentially, testing the second partner (usually the male partner) only after the first partner (typically the female partner) tests positive as a carrier for at least one condition [3]. Additionally, there are numerous options for CS gene panels, which differ in size and content [3]. Expanded carrier screening (ECS) panels continue to be offered to patients more frequently and increase the likelihood that an individual will be identified as a carrier [4, 5]. One study found that 77% of at-risk couples (ARC; both partners are carriers for the same recessive disease or the female partner is a carrier for an X-linked condition) identified with ECS pre-conceptually planned to alter their reproductive decisions [6].

CS is unique from other forms of prenatal screening because it can involve genetic screening for the male partner, providing an opportunity for male partners to participate in prenatal decision-making [7, 8]. Previous research has indicated females often make decisions regarding prenatal genetic screening with male partner input [9, 10]. In a few studies, pregnant females have cited their male partner’s reluctance to participate and concerns about partner disagreement regarding screening as potential barriers for their own uptake of CS [7, 11].

Past research has focused on female partners’ uptake of ECS to represent couples’ views and largely has not examined male partners’ participation or perspectives [12, 13]. A retrospective review found less than half of male partners pursued CS, when recommended, and called for the exploration of facilitators and barriers for male partner CS [14].

Assessment of male partner engagement in CS is needed to better include them in this process and inform clinical practice. This exploratory study investigated barriers and facilitators for male partners’ participation in ECS after their female partner was identified as a carrier, from both female and male perspectives.

Methods

The authors developed an online survey to explore the views of carrier females and their male partners on CS and the decision-making process.

Three surveys were created: (1) Female participants identified as a carrier for at least one autosomal recessive condition; (2) male participants who completed CS; and (3) male participants who did not complete CS. All research was conducted online in REDCap. This study was reviewed and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00210437).

Participants were patients who had testing with Myriad Genetics (formerly Counsyl) and genetic counseling through Northwestern Medicine (NM) or Insight Medical Genetics (IMG) in Chicago, IL, USA, from 2014 to November 2019. Females identified as a carrier were recruited by e-mail with the address associated with their testing record. Males who completed CS as patients at NM or IMG were recruited by e-mail with the address associated with their own testing record. The recruitment e-mail and survey included an explanation of ECS, a description of the study’s purpose, and survey links. Female participants whose partners did not complete CS were asked to forward a separate survey link to their male partners.

The surveys were not validated measures and were designed for the purpose of this study. Demographic information including age, race, marital status, level of education, religious affiliation, and income was gathered. Surveys focused on male partner roles in the CS process and barriers and facilitators for male partner involvement. Branching logic existed in the females’ survey, delineated by if their male partner had or had not pursued CS. Participants wrote in the condition(s) for which the female partner was identified as a carrier. Conditions were re-coded with the systematic classification of disease severity designed for ECS [15]. If multiple conditions were written, severity scoring reflected the most serious condition. No identifying data was collected from participants (see Online Resources 1-3).

Participants were required to be at least 18 years old and to read English. ARC were excluded to avoid risk of psychological harm and because of potential biases about the process. Females who used sperm donors to achieve pregnancy were also excluded. After completing the survey, participants could enter a raffle for one of four $200 gift cards.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (V26). Data analysis included frequency calculations for each question response; Mann-Whitney U tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and chi-square analyses to compare between-group responses; Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare within-group responses; and logistic regression to determine if independent variables predicted male partners’ pursuit of CS. Ordinal Likert scale data (four-item) was analyzed with non-parametric tests for group comparisons but was dichotomized into “agree” and “disagree” to determine top-ranked factors impacting male partners’ CS. Mean scores were calculated for participants’ Likert scale responses to show responses’ leaning because median scores were similar. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

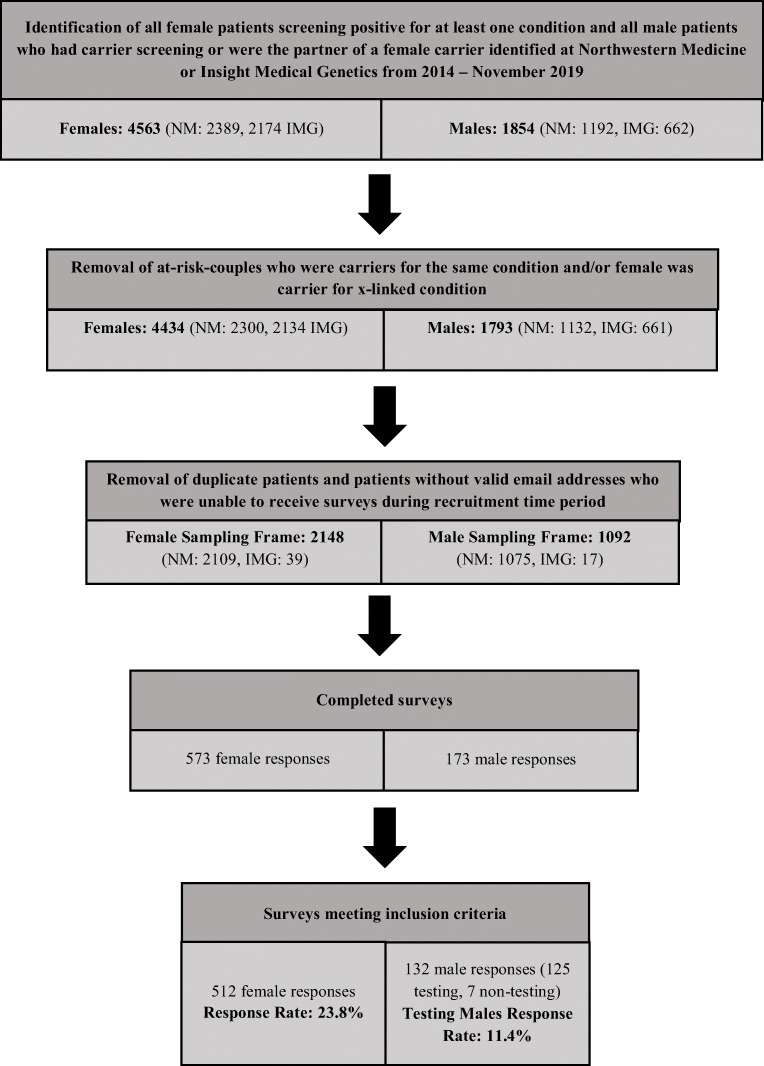

In total, 644 participants met study criteria and completed some or all of the survey (Fig. 1). From females, 512 surveys were returned for a response rate of 23.8%. Of those, 372 were females whose partners completed CS and 140 were females whose partners did not complete CS. From males who completed follow through CS, 125 surveys were returned for a response rate of 11.4%. Responses from an additional 26 males were not included because they initiated their own CS and would have had different motivations from males who pursued follow through CS after their female partner was identified as a carrier. From males who did not complete CS, seven surveys were returned; these were not included in analyses due to the sample size. Three groups were analyzed: females whose male partners completed CS (group 1), females whose male partners did not complete CS (group 2), and males who completed follow through CS (group 3).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of participant inclusion pipeline to demonstrate final number of responses analyzed. NM, Northwestern Medicine; IMG, Insight Medical Genetics

Table 1 lists demographic data. There were statistically significant differences between all three groups across relationship status, education level, household income, race, and if the male partner was at the initial appointment when the female partner elected ECS (hereafter referred to as “initial appointment”). Group 3 males were the most likely to be married (p = 0.000), identify as white (p = 0.001), and be at the initial appointment (p = 0.000). Group 1 females were the most likely to have a graduate degree (p = 0.031) and group 2 females were the most likely to report a lower income (p = 0.003).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants compared by group

| Variable | Group 1 females (n = 372) | Group 2 females (n = 140) | Group 3 males (n = 125) | Chi-square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | p | |

| Participant age | n = 367 | n = 137 | n = 123 | ||

| 20–24 | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11.390 | 0.077 |

| 25–34 | 172 (46.2%) | 66 (48.2%) | 51 (41.5%) | ||

| 35–44 | 192 (51.6%) | 65 (47.4%) | 68 (55.3%) | ||

| 45–48 | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (2.9%) | 4 (3.3%) | ||

| Relationship status | n = 357 | n = 134 | n = 119 | ||

| Single | 3 (0.8%) | 9 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 35.404 | 0.000*** |

| Married | 338 (94.7%) | 116 (86.6%) | 117 (98.3%) | ||

| Committed relationship | 12 (3.4%) | 7 (5.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Separated | 3 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Highest education level | n = 357 | n = 132 | n = 119 | ||

| No high school degree | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13.857 | 0.031* |

| High school degree/GED | 4 (1.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Some college/associate degree | 9 (2.4%) | 12 (9.8%) | 6 (5.0%) | ||

| Bachelor degree | 124 (34.7%) | 45 (34.1%) | 48 (38.4%) | ||

| Graduate degree | 220 (61.6%) | 72 (54.5%) | 64 (53.8%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Household income | n = 357 | n = 133 | n = 119 | ||

| < $50,000 | 5 (1.4%) | 8 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 33.383 | 0.003** |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 10 (2.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| $75,000–$99,999 | 9 (2.5%) | 6 (4.5%) | 5 (4.2%) | ||

| $100,000–$149,999 | 56 (15.7%) | 26 (19.5%) | 21 (17.6%) | ||

| $150,000–$199,999 | 60 (16.8%) | 28 (21.1%) | 25 (21.0%) | ||

| $200,000–$249,999 | 56 (15.7%) | 26 (19.5%) | 20 (16.8%) | ||

| $250,000 and greater | 134 (37.5%) | 30 (22.6%) | 43 (36.1%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 27 (7.6%) | 3 (2.3%) | 4 (3.4%) | ||

| Religious affiliation | n = 356 | n = 133 | n = 119 | ||

| Buddhist | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 23.241 | 0.107 |

| Catholic | 103 (28.9%) | 42 (31.6%) | 22 (18.5%) | ||

| Hindu | 3 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Jewish | 59 (16.6%) | 13 (9.8%) | 16 (13.4%) | ||

| Mormon | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Muslim | 4 (1.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Protestant | 46 (12.9%) | 21 (15.8%) | 14 (11.8%) | ||

| No religious affiliation | 113 (31.7%) | 48 (36.1%) | 56 (47.1%) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 16 (4.3%) | 5 (3.8%) | 6 (5.0%) | ||

| Other | 11 (3.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.4%) | ||

| Race | n = 351 | n = 133 | n = 113 | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 34.485 | 0.001*** |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 17 (4.8%) | 4 (3.0%) | 5 (4.4%) | ||

| Black/African American | 9 (2.6%) | 16 (12.0%) | 3 (2.7%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (2.6%) | 8 (6.0%) | 2 (1.8%) | ||

| White | 296 (84.3%) | 97 (72.9%) | 98 (86.7%) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.9%) | 4 (3.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Multiple races | 17 (4.8%) | 4 (3.0%) | 4 (3.5%) | ||

| Pregnant at testing | n = 372 | n = 140 | -- | ||

| Yes | 295 (79.3%) | 125 (89.3%) | -- | 6.88 | 0.009** |

| No | 77 (20.7%) | 15 (10.7%) | -- | ||

| Male at appointment | n = 357 | n = 135 | n = 125 | ||

| Yes | 177 (49.6%) | 48 (35.6%) | 99 (79.2%) | 52.499 | 0.000*** |

| No | 180 (50.4%) | 87 (64.4%) | 26 (20.8%) | ||

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

Further analyses demonstrated demographic differences between group 1 and group 2 females (Online Resource 4). Group 1 females were more likely to report being married (p = 0.000), having a graduate degree (p = 0.006), having a higher household income (p = 0.001), identifying as white (p = 0.000), and having their male partners at the initial appointment (p = 0.005). Group 1 females were less likely to be pregnant when they elected ECS (p = 0.009).

Predictors of male partner CS

To identify independent predictors of male partners’ pursuit of CS, the authors conducted a logistic regression with group 1 and group 2 females who provided demographic information included in the model (n = 440) (Table 2). Some categories were collapsed for analysis. Only the male partner’s attendance at the initial appointment independently predicted male partner CS (OR: 2.07, 95% CI 1.30–3.28). For every one-unit increase in males attending the appointment, a 0.726 increase in the log-odds of him getting screening is expected, holding all other independent variables constant.

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression for independent predictors of females’ male partners’ pursuit of carrier screening (n = 440)

| B | SE | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male partner at appointmenta | 0.726 | 0.235** | 2.067 | 1.30, 3.28 |

| Pregnantb | − 0.445 | 0.331 | 0.641 | 0.335, 1.23 |

| Marital statusc | 0.317 | 0.692 | 1.373 | 0.354, 5.33 |

| Religiond | ||||

| Christian | 0.348 | 0.379 | 1.416 | 0.674, 2.98 |

| Jewish | − 0.133 | 0.252 | 0.876 | 0.534, 1.44 |

| No religious affiliation | 0.550 | 0.642 | 1.734 | 0.492, 6.10 |

| Incomee | ||||

| $75,000–$99,999 | − 0.517 | 0.814 | 0.596 | 0.121, 2.94 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | − 0.292 | 0.612 | 0.747 | 0.225, 2.48 |

| $150,000–$199,999 | − 0.377 | 0.619 | 0.686 | 0.204, 2.31 |

| $200,000–$249,999 | − 0.122 | 0.629 | 0.885 | 0.258, 3.04 |

| More than $250,000+ | 0.421 | 0.613 | 1.523 | 0.458, 5.06 |

| Educationf | ||||

| Bachelor degree | 0.751 | 0.536 | 2.119 | 0.741, 6.06 |

| Graduate degree | 0.902 | 0.530 | 2.465 | 0.873, 6.96 |

| Raceg | ||||

| Black (African American) | − 1.303 | 0.56* | 0.272 | 0.091, 0.811 |

| Hispanic or Latino | − 0.489 | 0.568 | 0.613 | 0.202, 1.87 |

| Asian | − 0.076 | 0.619 | 0.927 | 0.276, 3.12 |

| Other | − 1.148 | 0.927 | 0.317 | 0.052, 1.95 |

| Multiple | 0.386 | 0.595 | 1.472 | 0.459, 4.72 |

| Constant | 0.025 | 0.866 | 1.026 | |

B, regression weight; SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Reference categories: aMale partner not at appointment, bfemale not pregnant at time of screening, cnon-partnered, dother, eless than $75,000, fless than a college degree, gwhite

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01

Condition severity

Associations between male partner CS and disease severity were assessed (Table 3). Of individuals from couples in which females were carriers of severe or profound conditions, 82.0% (114/139) reported the male partner had CS. This was significantly more than individuals from couples in which females were carriers for moderate conditions, of which 50.0% (21/42) reported the male partner had CS (p = 0.0000297).

Table 3.

Associations with male partners’ pursuit of carrier screening and condition for which female partner is a carrier

| Associations with male partner testing decisions and condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease severity categorization: moderate vs. severe/profound | |||

| Moderate | Severe/profound | Total | |

| Male partner tested | 21 | 114 | 135 |

| Male partner did not test | 21 | 25 | 46 |

| Total | 42 | 139 | p = 0.0000297*** |

| Biotinidase deficiency vs. other severe/profound conditions | |||

| Other severe/profound | Biotinidase deficiency | Total | |

| Male partner tested | 110 | 4 | 114 |

| Male partner did not test | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| Total | 126 | 13 | p = 0.000000435*** |

***p ≤ 0.001

Our results found 30.7% (4/13) of male partners of females identified as carriers of biotinidase deficiency (BTD) pursued CS compared to 87.3% (110/126) of male partners of females who were carriers for other severe or profound conditions (p = 0.000000435).

Facilitators and barriers

Factors impacting male partners’ pursuit of CS were divided into two categories: personal beliefs and logistics. Participants were asked how much they agreed or disagreed each factor impacted their male partner’s (groups 1 and 2) or their own (group 3) decision to have CS (four-item Likert scale). Group 1 and group 3 were asked about the same facilitators while group 2 was asked about possible barriers, some of which overlapped with facilitators (e.g., cost). Online Resources 5 and 6 display full Likert scale data.

The top reasons endorsed by group 1 and group 3 participants as impacting male partner CS coincided (Table 4). The three most strongly endorsed factors by group 1 females, with the highest proportion agreeing or strongly agreeing the factor impacted their male partner’s decision to pursue CS, were (1) “To alleviate female partner worry” (92.2%); (2) “Male partner liked that the test screened for many genetic conditions” (91.6%); and (3) “Male partner thought the overall process was simple and convenient” (89.4%). The three most strongly endorsed factors by group 3 males were (1) “Male partner thought the overall process was simple and convenient” (93.3%); (2) “Male partner wanted more information about risk for this pregnancy and future pregnancies” (92.7%); and (3) “Male partner liked that the test screened for many genetic conditions” (92.4%).

Table 4.

Comparisons between group 1 females and group 3 males for impact of facilitators on male partners’ decisions to pursue carrier screening

| Variables | Group 1 females (n = 372) | Group 3 males (n = 125) | Mann-Whitney U test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | A | D | M | Mdn | n | A | D | M | Mdn | p | |

| Personal beliefs | |||||||||||

| To alleviate female partner worry | 371 | 342 (92.2%) | 29 (7.82%) | 2.41 | 3.00 | 125 | 115 (92.0%) | 10 (8.00%) | 2.51 | 3.00 | 0.0551 |

| To alleviate male partner worry | 367 | 318 (86.6%) | 49 (13.4%) | 2.20 | 2.00 | 125 | 102 (81.6%) | 23 (18.4%) | 2.09 | 2.00 | 0.260 |

| Male partner wanted more information about risk for this pregnancy and future pregnancies | 370 | 312 (84.3%) | 58 (15.7%) | 2.21 | 2.00 | 123 | 114 (92.7%) | 9 (7.32%) | 2.39 | 2.39 | 0.0216* |

| Test information might have changed their reproductive decisions | 371 | 261 (70.3%) | 110 (29.6%) | 1.89 | 2.00 | 124 | 89 (69.4%) | 38 (30.6%) | 1.91 | 2.00 | 0.957 |

| Female partner told male partner to have carrier screening | 370 | 235 (63.5%) | 135 (36.5%) | 1.72 | 2.00 | 125 | 74 (59.2%) | 51 (40.8%) | 1.57 | 2.00 | 0.125 |

| Male partner was curious | 371 | 227 (61.2%) | 144 (38.8%) | 1.59 | 2.00 | 124 | 96 (77.4%) | 28 (22.6%) | 1.85 | 2.00 | 0.00335** |

| The condition(s) the female partner is a carrier of is concerning to male partner | 371 | 223 (60.1%) | 148 (39.9%) | 1.72 | 2.00 | 125 | 88 (70.4%) | 37 (29.6%) | 1.86 | 2.00 | 0.178 |

| We have a family history of genetic and/or medical conditions | 371 | 118 (31.8%) | 253 (68.2%) | 1.02 | 2.00 | 124 | 30 (24.2%) | 94 (75.8%) | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.966 |

| The risk for male partner to be a carrier seemed high | 370 | 54 (14.6%) | 316 (85.4%) | 0.71 | 1.00 | 124 | 13 (10.5%) | 111 (89.5)% | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.387 |

| Logistics | |||||||||||

| Male partner liked that the test screened for many genetic conditions | 357 | 327 (91.6%) | 30 (8.40%) | 2.24 | 2.00 | 119 | 110 (92.4%) | 9 (7.56%) | 2.40 | 2.00 | 0.0168* |

| Male partner thought the overall process was simple and convenient | 359 | 312 (89.4%) | 38 (10.6%) | 2.18 | 2.00 | 120 | 112 (93.3%) | 8 (6.67%) | 2.37 | 2.00 | 0.00817** |

| Male partner was aware carrier screening was recommended for him | 363 | 318 (87.6%) | 45 (12.4%) | 2.21 | 2.00 | 120 | 99 (82.5%) | 21 (17.5%) | 2.03 | 2.00 | 0.00961** |

| Male partner had the chance to have his questions answered at the appointment | 361 | 313 (86.7%) | 48 (13.3%) | 2.18 | 2.00 | 120 | 108 (90.0%) | 12 (10.0%) | 2.23 | 2.00 | 0.510 |

| Appointment times were convenient | 359 | 299 (83.3%) | 60 (16.7%) | 2.09 | 2.00 | 120 | 109 (90.8%) | 11 (9.17%) | 2.21 | 2.00 | 0.145 |

| Clear directions were provided by healthcare providers for male partner to have testing | 357 | 290 (81.2%) | 67 (18.8%) | 2.08 | 2.00 | 120 | 88 (73.3%) | 32 (26.7%) | 1.91 | 2.00 | 0.0180* |

| Male partner thought the cost was reasonable | 357 | 232 (65.0%) | 125 (35.0%) | 1.73 | 2.00 | 120 | 84 (70.0%) | 36 (30.0%) | 1.77 | 2.00 | 0.699 |

A, agree; D, disagree; M, mean; Mdn, median

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

Table 4 also demonstrates significant differences between group 1 females and group 3 males for several factors. Some factors were strongly endorsed by both groups but there were between-group differences about their reported impact. Group 3 males more strongly agreed they pursued CS because they “wanted more information about the risk for this pregnancy and future pregnancies” (p = 0.022) and “were curious” (p = 0.003). Group 3 males also more strongly agreed they “liked that the test screened for many genetic conditions” (p = 0.017) and they “thought the overall process was simple and convenient” (p = 0.008). Group 1 females more strongly agreed their male partner’s pursuit of CS was impacted because “clear directions were provided by healthcare providers for [him] to have testing” (p = 0.018) and “[he] was aware CS was recommended for him” (p = 0.010).

Table 5 shows barriers endorsed by group 2 female participants as impacting their male partner’s decision not to pursue CS. The three most strongly endorsed factors by group 2 females, with the highest proportion agreeing or strongly agreeing the factor impacted their male partner’s decision, were (1) “The risk for him to be a carrier seemed low” (75.0%); (2) “The condition(s) I am a carrier of is not concerning to him” (65.0%); and (3) “Test information would not change our reproductive decisions” (58.6%).

Table 5.

Group 2 females impact of barriers on male partners’ decisions not to pursue carrier screening

| Variables | Group 2 females (n = 140) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | A | D | M | Mdn | |

| Personal beliefs | |||||

| The risk for him to be a carrier seemed low | 140 | 105 (75.0%) | 35 (25.0%) | 1.97 | 2.00 |

| The condition(s) I am a carrier of is not concerning to him | 140 | 91 (65.0%) | 49 (35.0%) | 1.81 | 2.00 |

| Test information would not change our reproductive decisions | 140 | 82 (58.6%) | 58 (41.4%) | 1.68 | 2.00 |

| He does not have a family history of genetic and/or medical problems | 140 | 68 (48.6%) | 72 (51.4%) | 1.36 | 1.00 |

| The condition is on the Newborn Screening Panel and we could wait until birth to find out | 138 | 31 (22.5%) | 107 (77.5%) | 0.75 | 0.00 |

| He was confused about the purpose for testing | 139 | 14 (10.1%) | 215 (89.9%) | 0.39 | 0.00 |

| It would be upsetting to him to learn this information | 138 | 7 (5.07%) | 131 (94.9%) | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| He does not think genetic testing should be performed for any reason | 140 | 5 (3.57%) | 135 (96.4%) | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| He was fearful of privacy with his genetic information | 140 | 3 (2.14%) | 137 (97.9%) | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Logistics | |||||

| He thought the cost was unreasonable | 139 | 33 (23.7%) | 106 (76.3%) | 0.81 | 1.00 |

| He did not have information about insurance coverage | 138 | 26 (18.8%) | 112 (81.2%) | 0.67 | 0.00 |

| He was unable to take time off from work | 139 | 17 (12.2%) | 122 (87.8%) | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| He was not aware carrier screening was recommended for him | 138 | 16 (11.6%) | 122 (88.4%) | 0.56 | 0.00 |

| Lack of convenient appointment times | 139 | 12 (9.35%) | 126 (90.6%) | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| He has a fear of blood draws | 139 | 12 (8.63%) | 127 (91.4%) | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| He did not think clear directions to have testing were provided by healthcare providers | 139 | 10 (7.19%) | 129 (92.8%) | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| The overall process was too complicated | 137 | 9 (6.57%) | 128 (93.4%) | 0.45 | 0.00 |

A, agree; D, disagree; M, mean; Mdn, median

Group 1 and group 2 response scores for the same factors impacting male partner CS were compared (Online Resource 7). There were no significant differences for the impact of the male partner’s level of concern about the condition(s) for which the female partner was a carrier (p = 0.333) and for the results’ potential to change couples’ reproductive decisions (p = 0.098).

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests demonstrated within-group differences for the impact of logistic and personal belief factors on male partners’ CS decisions (Online Resource 8). There was a significant difference between the median total scores for logistic (Mdn = 2.00) and personal belief (Mdn = 1.67) factors for group 1 females (p = 0.000). Group 3 males also reported higher scores for logistic (Mdn = 2.00) than personal belief (Mdn = 1.78) factors (p = 0.000). Both group 1 and group 3 participants reported significantly higher total median scores for logistic factors than personal belief factors as impacting male partners’ pursuit of CS. There was also a significant difference between the median total scores for logistic (Mdn = 0.375) and personal belief (Mdn = 1.00) factors for group 2 (p = 0.000). Group 2 participants agreed more strongly that personal belief factors impacted their male partner’s decision not to pursue CS.

Male and female partners’ decision-making

Most group 3 males (91.2%) reported they were aware CS could be recommended for them if their female partner was identified as a carrier. A high proportion (94.7%) of group 3 participants who were at the initial appointment reported the provider involved them in the decision-making process. Almost one-third (31.9%) of group 3 males desired more male partner involvement in the CS process. Over one-third (36.5%) of group 3 participants reported that CS increased their feelings of involvement in the pregnancy.

Participants were asked how much they and their partner agreed about the male partner’s CS decision. Associations between male partner CS and between-partner agreement were assessed (Online Resource 9). Of individuals in couples in which the male partner pursued CS, 96.3% (462/480) reported they and their partner agreed with the male partner’s decision to have CS. This was significantly higher than the 87.5% (91/104) of group 2 females who reported they and their partner agreed about his decision not to have CS (p = 0.000308). Of group 2 females, 75.0% said they discussed the recommendation for their partner to have CS with him.

All participants were asked which parties or healthcare providers should have the primary responsibility for explaining the purpose and logistics of follow through CS to male partners. Across all groups, the majority of participants said genetic counselors should have the primary responsibility (Online Resource 10).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess factors impacting male partners’ pursuit of CS after their female partner was identified as a carrier, from both female and male partners’ perspectives. The results highlight several important factors and demonstrate areas for further research.

The results of this study indicated female partners’ demographic features did not independently predict male partners’ pursuit of CS.

The odds of male partners who attend the initial appointment getting CS is 2.07 times the odds of male partners who did not attend the initial appointment. These data support that females and their providers should encourage male partners to attend the appointment when CS is offered to be most effective. The majority (79.2%) of group 3 males attended the initial visit (Table 1) and most (94.7%) of these participants reported the provider involved them in the decision-making process. Most (91.2%) male partners reported they understood CS would be recommended for them if their female partner was identified as a carrier. Some (36.5%) males self-reported that having CS also increased their overall involvement in the pregnancy. This coincides with male partners’ perceived increased involvement in prenatal decision-making when providers include their perspectives [16]. These results suggest that overall, male partners who had CS reported feeling involved and informed. Still, almost one-third of group 3 males reported they wanted to be more involved in the process.

Our study indicates the severity of the condition(s) for which the female partner is a carrier could impact male partners’ pursuit of CS. Both groups of female participants reported the severity of the condition for which they are a carrier impacted their male partner’s decision. The second most endorsed factor by group 2 females was that the condition they were a carrier for was not concerning to their male partner. Male partners were more likely to have screening if the female partner was a carrier for a more serious condition, with 82.0% of male partners of females identified as carriers for severe or profound conditions having CS compared to 50.0% of male partners of females identified as carriers for moderate conditions. These findings are consistent with previous studies, but because condition severity is modified by factors like treatment availability, counseling about condition severity could has varied [6, 15, 17].

Previous research has demonstrated differences in reproductive decision-making for couples identified as carriers of BTD, a condition classified as profoundly severe based on untreated disease course [17]. Results of this study support this difference. The difference between the number of male partners who pursued CS for BTD (30.7%) compared to other severe or profound conditions (87.3%) further demonstrates the complexity of severity scaling. BTD is classified as profoundly severe but the common D444H variant (allele frequency of 3.18% in gnomAD) is associated with a partial deficiency and less severe presentation [18]. Additionally, treatment availability modifies condition severity and BTD symptoms can be treated with pharmacological biotin doses, which could impact decision-making [15, 19]. Newborn screening (NBS) also screens for BTD, and although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recognized NBS does not diminish the potential benefits of CS, knowing their offspring will have postnatal testing via NBS may decrease the importance for couples to take actions prenatally [6, 19, 20]. The difference between male partner follow through CS for BTD compared to other severe or profound conditions provides one example of the complications in assessing drivers of clinical utility.

If a male partner reviews information about the condition for which his partner is a carrier then specifically decides the condition is not severe or common enough to test himself, there is low clinical utility. There seems to be a disconnect between how participants indicated the test’s ability to screen for many conditions impacted male partners’ decisions to pursue CS and that the severity of the condition for which the female partner was a carrier for was also impactful. These results feed into a larger debate about which genetic conditions should be on CS panels and which factors, like carrier frequency or condition severity, drive clinical utility [21]. Genetic testing laboratories could consider evidence regarding follow through CS in partners, in addition to their own data, in determining which conditions to include or remove from their CS panels to maximize clinical utility. This study supports the value of patient perspectives in these discussions of clinical utility both on a larger scale, when designing CS gene panels, and in individual patient interactions, when engaging in shared decision-making regarding CS options with patients. These data reinforce these decisions should be driven by patient-focused care perspectives. We need to further understand decision-making behaviors, of which partners choose to pursue CS and how they use that information, as more individuals will continue to be identified as carriers for genetic conditions as ECS panels grow in size [5].

This study found preliminary evidence for many factors impacting male partner follow through CS. Group 1 females and group 3 males largely agreed about factors impacting male partners’ pursuit of CS. However, there were between-group differences on several factors. Both groups agreed the overall ease of the process facilitated male partner CS, but males agreed even more strongly that it impacted their decision. Males were more likely to agree that wanting more information about the risk for their future children and liking that the test screened for many conditions impacted their screening decision. This aligns with previous research that demonstrated males take on a “fact manager” role when a pregnancy is indicated to be at higher risk for genetic abnormalities [22]. Although males reported interest in a test screening for many conditions, insurance coverage for their own testing often depends on female partners’ results, which might limit them to testing only for the conditions for which the females were carriers [20, 23, 24]. This is of particular consideration for males pursuing follow through CS in a sequential manner and limits the clinical utility for males interested in a comprehensive understanding of their carrier status for multiple conditions.

ECS has the most clinical utility when both partners participate. Understanding where breakdowns occur in the screening process allows providers to support both partners’ perspectives. Logistic barriers were not reported as the main deterrent impacting why female participants’ male partners did not pursue CS. The data suggests once male partners are aware their female partner is a carrier, their pursuit of CS is impacted more by personal belief factors.

After the female partner is identified as a carrier, couples assess factors like condition severity and the risk for the male partner to be a carrier. Those who appraise this “threat” as significant may utilize CS to clarify the risk. Stress and coping research suggests individuals examine a threat’s severity and personal relevance via primary appraisal, then apply emotion-focused and/or problem-focused coping strategies for threats appraised as significant [25]. Male partners reported the ability to gain more information about the risk to their offspring impacted their decision to have CS, and their pursuit of CS could be a problem-focused coping mechanism utilized to gain more information to better understand the threat. Previous research has indicated genetic testing is a coping mechanism for individuals who believe testing can decrease uncertainty about genetic risk [26]. One study found the underlying facilitator for females to pursue CS was the “desire to do ‘everything possible’ to protect the health of their offspring” [11]. The results of this study suggest male partners’ CS could be similarly motivated by the same desire and introduces how male partner CS could be facilitated by risk appraisals for their offspring.

However, couples may also appraise the “threat” as not significant enough to warrant male partner CS. Group 2 females reported personal belief factors, like the perceived low risk for him to be a carrier for the same condition, primarily deterred their male partners from screening. These results demonstrate the value of discussing personal belief factors, like risk perception, when providers discuss CS with even just the female patient if her partner is not present. Additionally, the majority of participants believed genetic counselors should have the primary responsibility for explaining the purpose and procedure for male partners’ follow through CS. These are further reasons to encourage male attendance at the CS visit.

It is worth noting that all but possibly a few participants underwent genetic counseling. Both female groups reported the CS results’ possible influence on reproductive decision-making similarly impacted their male partners’ screening decisions. Genetic counselors can employ anticipatory guidance to consider implications of female CS results including testing for male partners and other reproductive options if couples are identified to be at-risk.

Our study provides conflicting evidence for whether the low rate for male partner follow through CS is driven by females or their male partners [14]. Significantly more group 2 females reported disagreement between them and their male partners about his screening decision (12.5%) than individuals in couples in which the male partner had CS (3.75%). This suggests more of these females wanted their male partners to pursue CS, so the decision not to have screening was male partner-driven. However, one-fourth of group 2 females reported they did not discuss the recommendation for their male partner to have screening with him, suggesting some male partners do not pursue CS because their female partner does not communicate this recommendation to him. More targeted research is needed to understand this research question.

The limitations of this study indicate future areas for research. The indirect recruitment method for males who did not pursue CS led to a small sample size which could not be included in analyses. Perspectives from these male partners would be valuable in furthering the understanding of this topic. Qualitative studies examining this group’s decision-making in the CS process would be beneficial and could inform future studies comparing perspectives of male partners who do or do not pursue CS.

This study was also limited because study participants were not diverse nor representative across multiple demographic factors, including race and annual household income. Social determinants of health have been demonstrated to impact health-related decision-making; therefore, this sample’s endorsements of various facilitators and barriers for CS could differ from those of a more diverse population’s [27]. Additionally, participants were recruited through centers whose genetic counselors order carrier screens, biasing the population to their support. Further studies examining this topic in other healthcare settings, with a patient population more representative of the general population and where genetic counselors are not coordinating CS, are recommended.

Conclusion

This study begins to describe the role of male partners in the ECS process. Males who attended females’ CS appointments were more likely to pursue CS. These data support the logistics of the current CS process for males. Many factors impact how male and female partners appraise the reproductive risk of the female partner’s carrier status, which subsequently impacts if these male partners pursue CS. Female partners of males who did not have CS endorsed that personal-belief factors seem to be more important for their male partners’ decisions.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 125 kb).

(PDF 118 kb).

(PDF 119 kb).

(PDF 94 kb).

(PDF 85 kb).

(PDF 58 kb).

(PDF 78 kb).

(PDF 66 kb).

(PDF 62 kb).

(PDF 42 kb).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the individuals who made this study possible, including patients who participated in the research and the Northwestern University Graduate Program in Genetic Counseling, who provided funding for this Master’s thesis project. This study was performed by first author Sarah Jurgensmeyer in fulfillment of a Master of Science in Genetic Counseling training program.

Funding

The Northwestern University Graduate Program in Genetic Counseling provided funding for this Master’s thesis project.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Kenny Wong is a consultant of Myriad Genetics, Inc. and chair of Access to Expanded Carrier Screening Coalition. Authors Sarah Jurgensmeyer, Sarah Walterman, Andrew Wagner, Annie Bao, Sarah Stueber, and Sara Spencer report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00210437).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Committee on Genetics ACOG technology assessment in obstetrics and gynecology no. 14: modern genetics in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(3):e143–e168. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ropers HH. On the future of genetic risk assessment. J Community Genet. 2012;3(3):229–236. doi: 10.1007/s12687-012-0092-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henneman L, Borry P, Chokoshvili D, et al. Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(6):e1–e2. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briggs A, Nouri PK, Galloway M, O’Leary K, Pereira N, Lindheim SR. Expanded carrier screening: a current survey of physician utilization and attitudes. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(9):1631–1640. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1272-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neitzel D, Glass S, Leahey J, Faulkner N. Carrier screening: should evaluating more genes be the standard of care? Fertil Steril. 2019;111(4):e33–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taber KA, Beauchamp KA, Lazarin GA, et al. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: results-guided actionability and outcomes. Genet Med. 2019;21(5):1041–1048. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mennie ME, Gilfillan A, Compton ME, Liston WA, Brock DJH. Prenatal cystic fibrosis carrier screening: factors in a woman’s decision to decline testing. Prenat Diagn. 1993;13(9):807–814. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970130904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed K. ‘It’s them faulty genes again’: women, men and the gendered nature of genetic responsibility in prenatal blood screening. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(3):343–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell RM, Agatisa PK, Mercer MB, et al. Expanded indications for noninvasive prenatal genetic testing: implications for the individual and the public. Ethics, Med. Public Health. 2016;2(3):383–391. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis C, Hill M, Skirton H, Chitty LS. Development and validation of a measure of informed choice for women undergoing non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(6):809–816. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider JL, Goddard KA, Davis J, et al. “Is it worth knowing?” Focus group participants’ perceived utility of genomic preconception carrier screening. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(1):135–145. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9851-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilmore MJ, Schneider J, Davis JV, Kauffman TL, Leo MC, Bergen K, Reiss JA, Himes P, Morris E, Young C, McMullen C, Wilfond BS, Goddard KAB. Reasons for declining preconception expanded carrier screening using genome sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(5):971–979. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Propst L, Connor G, Hinton M, Poorvu T, Dungan J. Pregnant women’s perspectives on expanded carrier screening. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(5):1148–1156. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giles Choates M, Stevens BK, Wagner C, et al. It takes two: uptake of carrier screening among male reproductive partners. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40(3):311–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lazarin GA, Hawthorne F, Collins NS, et al. Systematic classification of disease severity for evaluation of expanded carrier screening panels. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bäckström C, Thorstensson S, Mårtensson LB, et al. ‘To be able to support her, I must feel calm and safe’: pregnant women’s partners perceptions of professional support during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):234. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1411-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghiossi CE, Goldberg JD, Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Wong KK. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: reproductive behaviors of at-risk couples. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(3):616–625. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wolf B. Biotinidase deficiency: “if you have to have an inherited metabolic disease, this is the one to have”. Genet Med. 2012;14(6):565–575. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee on Genetics Committee opinion no. 690: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e35–e40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Shachar R, Svenson A, Goldberg JD, Muzzey D. A data-driven evaluation of the size and content of expanded carrier screening panels. Genet Med. 2019;21(9):1931–1939. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Åhman A, Lindgren P, Sarkadi A. Facts first, then reaction—expectant fathers’ experiences of an ultrasound screening identifying soft markers. Midwifery. 2012;28(5):e667–e675. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cigna. Genetic testing for reproductive carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis. 2019.

- 24.BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina. Genetic testing for cystic fibrosis AHS – M2017. 2019.

- 25.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lerman C, Croyle RT, Tercyak KP, Hamann H. Genetic testing: psychological aspects and implications. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(3):784–797. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.3.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 125 kb).

(PDF 118 kb).

(PDF 119 kb).

(PDF 94 kb).

(PDF 85 kb).

(PDF 58 kb).

(PDF 78 kb).

(PDF 66 kb).

(PDF 62 kb).

(PDF 42 kb).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.