Abstract

Objective

Telomeres are repetitive sequences localized at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes comprising noncoding DNA and telomere-binding proteins. TRF1 and TRF2 both bind to the double-stranded telomeric DNA to regulate its length throughout the lifespan of eukaryotic cells. POT1 interacts with single-stranded telomeric DNA and contributes to protecting genomic integrity. Previous studies have shown that telomeres gradually shorten as ovaries age, coinciding with fertility loss. However, the molecular background of telomere shortening with ovarian aging is not fully understood.

Methods

The present study aimed to determine the spatial and temporal expression levels of the TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins in different groups of human ovaries: fetal (n = 11), early postnatal (n = 10), premenopausal (n = 12), and postmenopausal (n = 14). Also, the relative telomere signal intensity of each group was measured using the Q-FISH method.

Results

We found that the telomere signal intensities decreased evenly and significantly from fetal to postmenopausal groups (P < 0.05). The TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins were localized in the cytoplasmic and nuclear regions of the oocytes, granulosa and stromal cells. Furthermore, the expression levels of these proteins reduced significantly from fetal to postmenopausal groups (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that decreased TERT and telomere-binding protein expression may underlie the telomere shortening of ovaries with age, which may be associated with female fertility loss. Further investigations are required to elicit the molecular mechanisms regulating the gradual decrease in the expression of TERT and telomere-binding proteins in human oocytes and granulosa cells during ovarian aging.

Keywords: Ovarian aging, Telomere, TERT, Telomere-binding proteins

Introduction

Telomeres are repetitive noncoding DNA sequences localized at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes that consist primarily of telomeric DNA and telomere-binding proteins [1]. Telomeric DNA is composed of a long array of double-stranded TTAGGG repeats and a single-stranded 3′ overhang. The 3′ overhang enters the double-stranded telomeric duplex to create T- and D-loop structures. Telomeres are directly bound by telomere repeat-binding factors including telomeric repeat-binding factor 1 (TRF1), telomeric repeat-binding factor 2 (TRF2), and protection of telomeres 1 (POT1) and indirectly associated with repressor/activator protein 1 (RAP1), TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2 (TIN2), and TIN2-interacting protein 1 (TPP1). These six proteins form a complex called “shelterin complex” or “telosome” that maintains telomere length and protects telomeres from DNA-damage-response activation [2].

The TRF1 and TRF2 proteins bind to the double-stranded telomeric DNA and function in maintaining telomere length homeostasis by repressing telomerase-dependent telomeric elongation [3]. TRF2 also plays roles in inhibiting both double-strand break response activation and ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase pathway at the telomeres as well as in the attachment of telomeres to the nuclear envelope [4]. While the long-term overexpression of TRF1 results in progressive telomere shortening, a lack of TRF1 leads to telomere elongation [5]. Similarly, TRF2 overexpression inhibits telomere lengthening [3] while a deficiency causes telomeric instability entailing fusion of chromosome ends and DNA-damage-response activation [6]. A limited number of studies reported that TRF1 localizes in the nucleus of 2-cell and blastocyst-stage mouse embryos [7] and the nuclear region of murine fibroblasts [8]. Analogously, TRF2 resides in nuclei of cumulus cells, oocytes obtained from mouse antral follicles [9], and fetal human oocytes [10]. Another telomere repeat-binding factor, POT1, interacts with the single-stranded part of telomeres. It represses ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) protein-mediated telomeric DNA damage response and stimulates helicases to unwind the telomeric duplex during DNA replication [11, 12]. A lack of POT1 results in the disappearance of G-overhang, rapid telomere elongation, and DNA-damage-response activation [13, 14]. The nuclear localization and functional importance of POT1 at the telomeres were characterized in somatic [15] and cancer cells [16]. To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the spatial and temporal expression of these telomeric repeat–binding proteins in human ovaries.

When the telomere length shortens due to consecutive DNA replication and/or genotoxic agents, it then elongates via the enzyme telomerase. Telomerase is found in fetal tissues, germ cells, granulosa cells, early embryos, stem cells, and tumor cells. It is a ribonucleoprotein composed of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), telomerase RNA component (TERC), and accessory proteins such as dyskerin (DKC), non-histone protein 2 (NHP2), nucleolar protein 10 (NOP10), and telomerase Cajal body protein 1 (TCAB1). The catalytic subunit, TERT, synthesizes the telomeric DNA sequences using TERC as a template in cooperation with the accessory proteins [1]. The TERT mRNA expression was detected in the germinal vesicle (GV) and metaphase I (MI) and metaphase II (MII) oocytes as well as in day-3 and blastocyst-stage embryos in humans [17]. Consistent with its known mission, TERT resides in the nuclei of GV oocytes and granulosa cells of the primary and preantral follicles in the pig ovaries [18]. Notably, the cellular distribution of TERT in the antral follicles is only in the layers of mural granulosa and cumulus cells of the antral follicles and in the cytoplasm of oocytes in the antral follicles [18]. In humans, TERT localizes in the nucleus of fetal oocytes at the prophase of first meiosis [10]. Also, Dundee et al. (2015) observed TERT in nuclei of granulosa cells of the follicles from primary to antral stages in human ovaries, but in the cytoplasm of the cultured granulosa cells [19]. When telomerase activity was examined in human oocytes and early embryos, it was found in GV and MII oocytes, as well as in the early stages of embryonic development from zygote to blastocysts [20]. The GV oocytes and blastocysts had significantly higher telomerase activity compared with the MII oocytes and early embryos, and immature oocytes showed higher telomerase activity than mature oocytes [20]. Consistent with having higher telomerase activity, GV oocytes and blastocysts in humans exhibited longer telomeres compared with the cleavage-stage embryos [21].

As is known, age-related decline in female reproduction, to a great extent, originates from the depletion of oocyte reserves and antral follicles [22, 23]. Furthermore, physiological changes such as decreased oocyte quality [24–26], impaired hypothalamic-pituitary ovarian axis [27, 28], disrupted oocyte-granulosa cell cross-talk, and mitochondrial dysfunction occur with ovarian aging [29]. Indeed, the ovarian reserve and fertility characteristics are highest around 20-30 years of age, followed by a significant decrease initiating around 35 years of age [30]. The gradual loss of fertility with aging is largely attributed to telomere shortening (reviewed in [31]), which also progresses with aging (reviewed in [32]) possibly due to decreasing telomerase activity [33]. During the last several decades, child-bearing has been delayed due to socioeconomic factors; therefore, understanding the molecular background of telomere shortening in human ovaries with aging acquires more importance. In this study, we hypothesized that the altered expression of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins may contribute to telomere shortening as the ovaries age. Among the telomere-linked proteins, we selected the TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins since they directly interact with the telomeric sequences to regulate the elongation and structural integrity of telomeres. Therefore, the spatiotemporal expression of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins, as well as telomere signal intensities, were evaluated in the fetal, early postnatal, premenopausal, and postmenopausal human ovaries.

Material and methods

Sample collection

Paraffin blocks of human ovaries were obtained from the archives of the Akdeniz University School of Medicine, Department of Pathology. This human subject research was approved by the Akdeniz University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 662, Date: December 14, 2016). The fetal ovaries (n = 11) were retrieved from intrauterine deaths or terminations during the prenatal period of 19 to 42 weeks (mean ± standard deviation: 26.55 ± 8.66 weeks old). We obtained the early postnatal ovaries from newborns under 1-month-old (n = 10) who were experiencing cysts or torsion but did not have chromosomal abnormalities, genito-pelvic anomalies, maceration, or metabolic diseases as in the fetal group. The premenopausal ovaries (32-46 years old, 41.58 ± 4.29 years old; n = 12) were collected from patients suspected of having ovarian tumors based on biochemical, physical, or ultrasound examinations, along with patients who underwent total hysterectomies or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies. The postmenopausal ovaries (53-71 years old, 58.79 ± 6.36 years old; n = 14) were obtained from patients diagnosed with prolapsed uterus or cervix. While patients with myoma uteri, simple follicular cyst, or endometriosis were included, those with endometrial or ovarian malignancies or ovarian large cysts or tumors were excluded from the study. Notably, all pre- and postmenopausal patients were fertile and had possessed at least one live birth.

Paraffin embedding and histopathological analysis

The human ovary samples were prepared using a standard protocol for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue processing. Briefly, samples were fixed with 10% buffered formalin overnight, dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Serial cross-sections 5-μm-thick were cut from the paraffin blocks using a rotary microtome (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and mounted on superfrost plus slides (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), which were later used for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) or immunohistochemical staining. The HE-stained slides were analyzed to determine the histopathological status of the human ovaries. We divided the human ovary samples into four groups: fetal, early postnatal, premenopausal, and postmenopausal. Furthermore, we counted the follicles from primordial to antral stages, and atretic follicles as well in the randomly selected human ovary sections as with the mouse ovaries in our previous study [34]. The follicular classification was conducted based on the following criteria [35]: While primordial follicles had oocytes surrounded by a single layer of squamous pre-granulosa cells, we defined the primary follicles as having oocytes enclosed by a layer of cuboidal granulosa cells. The secondary follicles were composed of two or more layers of cuboidal granulosa cells surrounding the oocytes, but without visible space among granulosa cells. Follicles with small spaces among granulosa cells and centrally localized oocytes were classified as preantral follicles (also known as early antral follicles). The small spaces coalesce into a single large antrum filled with follicular fluid in the antral follicles, displaying eccentrically localized oocytes. The atretic follicles were distinguished by structurally disrupted oocytes, abnormal zona pellucida, and granulosa cell clusters. Additionally, corpus luteum having granulosa and theca lutein cells (displaying eosinophilic staining) and corpus albicans (a regressed form of corpus luteum) composed of connective tissue were counted. Overall, for each cross-section of the HE-stained human ovaries, we determined the number of each follicle type, atretic follicles, and corpus luteum and corpus albicans structures.

Immunohistochemistry

The spatial and temporal expression of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins in the human ovaries were examined using immunohistochemistry, as in our previous study [36]. The paraffin sections were deparaffinized in fresh xylene and then rehydrated in a series of decreasing ethanol concentrations. After deparaffinization and rehydration processes, citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was treated for antigen retrieval using a microwave oven (750 W, 2 × 5 min). Endogenous peroxidase activity in the sections was blocked by applying 3% hydrogen peroxide prepared in methanol for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Following several washes with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), sections were treated with ultra-v blocking solution (Thermo Scientific) at RT for 7 min to prevent non-specific binding. Then, we incubated sections with the following primary antibodies that were produced in rabbits: TERT (1 μg/μl, 1:350; catalog no. BS0233R, Bioss, MA, USA), TRF1 (1 μg/μl, 1:300; catalog no. BS-1151R, Bioss), TRF2 (1 mg/ml, 1:200; catalog no. NB110-57130, Novus Bio., Centennial, CO, USA), and POT1 (0.3 μg/μl, 1:100; catalog no. 10581-1-AP, Proteintech, Chicago, USA) at 4 °C overnight. One of three sections on each slide was incubated with an antibody isotype (2.5 mg/ml, catalog no. 3900S, Cell Signaling, Leiden, Netherlands) to test the specificity of the primary antibodies. After that, each section was washed three times in PBS for 15 min and subsequently incubated with anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (1:500; Vector Labs, Peterborough, UK) at RT for 1 h. Finally, we incubated sections with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) complex (Thermo Scientific) for 20 min at RT. Following 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) chromogen treatment, the immunoreactivity in each section was evaluated using a light microscope. Then, we washed sections in running tap water and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The immunoexpression of the TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins in the fetal (n = 11), early postnatal (n = 10), premenopausal (n = 12), and postmenopausal (n = 14) was examined and captured under a bright-field microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). In each group, we evaluated at least 20 primordial and 10 primary follicles with normal appearance. The relative intensity of the immunostaining and cellular distribution of these proteins in each group was analyzed using ImageJ software [National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA]. The captured micrographs were converted into gray values to determine the integrated mean values of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins above the threshold. Finally, we found the mean intensity of the target proteins in each group by averaging the integrated mean values from the analyzed area, as in our previous study [37].

Quantitative fluorescent in situ hybridization

The quantitative fluorescent in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) applied in this study was adapted from the study by Aida et al. [38]. We analyzed the intensity of telomere signals in the fetal (n = 6), early postnatal (n = 6), premenopausal (n = 6), and postmenopausal (n = 6) ovary groups. The human ovary sections were incubated in an oven at 60 °C for 30 min. Then, sections were held in xylene for 7 min, rinsed in absolute ethanol, and air-dried. We incubated sections in 0.2 M HCl for 15 min and washed 2 × 5 min in distilled water. Sections were then incubated in 1 M NaSCN for 35 min at 80 °C and rinsed with distilled water, followed by enzymatic digestion with 1 mg/ml pepsin solution for 15 min at 37 °C and a 2 × 5 min washing with distilled water. Thereafter, sections were rinsed in absolute ethanol and then air-dried. The sections were treated with 0.5 mg/ml ribonuclease A at 37 °C for 15 min, rinsed with PBS, dehydrated through an ethanol series (70%, 90%, and 100%), and subsequently air-dried. Next, we incubated sections at 80 °C for 3 min and then for 1 h at RT with a 0.43 μg/ml peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe (telo C Cy3 probe: 5′-CCCTAACCCTAACCCTAA-3′V) to detect the telomeric repeat sequences. After the probe incubation, we washed the sections 3 × 15 min in 70% formamide buffer, followed by washing with a TBTT buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.08% Tween 20) for 4 × 5 min, dehydrating through an ethanol series (70%, 90%, and 100%), and air-drying. For the nuclear staining, sections were stained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) for 1 min and then covered with a coverslip using a mounting media. The relative telomere signal intensity in the human ovary groups was evaluated using ImageJ software (NIH), as in the previous investigations [38, 39]. The captured Q-FISH micrographs were converted into gray values to determine the integrated mean values of the telomere signal above the threshold. Finally, we identified the mean intensity of telomere signals in each group by averaging the integrated mean values from the analyzed area, as in our recently published study [40].

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the results was analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks, a non-parametric method of testing, followed by Dunn’s or Tukey’s post hoc test. We conducted the statistical calculations using SigmaStat for Windows, version 3.5 (Jandel Scientific Corp). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Histopathology of human ovaries

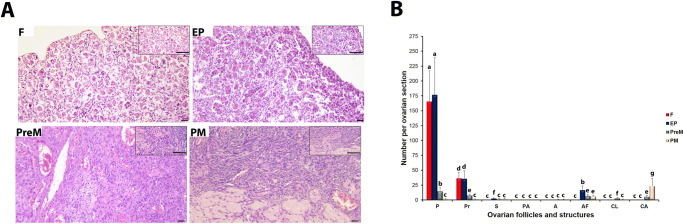

The human ovary sections stained with HE were analyzed for their histopathologic characteristics (Fig. 1a). Based on their histological structures and ages, we classified the human ovaries into four groups: fetal, early postnatal, premenopausal, and postmenopausal. The fetal ovaries included many primordial follicles in the stroma of the cortex undergoing development. In the early postnatal group, as gonadotropin-independent follicular development was initiated, primary follicles were observed in addition to primordial follicles. All follicular stages from primordial to antral, as well as the formation of corpus luteum and corpus albicans structures, were observed in the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups. When the follicles (normal and atretic) and the ovarian structures were counted (Fig. 1b), we found significantly fewer primordial and primary follicles in the premenopausal group, and even fewer in the postmenopausal group, in comparison with the fetal and early postnatal groups (P < 0.05). Notably, we observed very few secondary, preantral, and antral follicles in all ovary groups, from fetal to postmenopausal. The number of atretic follicles was lowest in the fetal group, dramatically increased in the early postnatal group, and decreased in the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups (P < 0.05). On the other hand, we detected the highest corpus luteum and corpus albicans numbers in the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Histopathology and numbers of the follicles and ovarian structures in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Representative hematoxylin-eosin (HE)-stained micrographs of the ovary groups. Based on our histopathological analysis, primordial and primary follicles were present in the human ovary sections of all four groups. We observed the ovarian structures, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans, in the PreM and PM groups. The relevant insert of each micrograph is presented in the upper right corner. These micrographs and inserts were captured at × 200 and × 400 original magnifications, respectively. The scale bars are 50 μm in length. b Follicle (from primordial to antral stages, as well as atretic follicles), corpus luteum, and corpus albicans numbers per section. Although the numbers of primordial and primary follicles significantly decreased from F to PM groups (P < 0.05), we detected very few secondary, preantral, and antral follicles in these groups. The atretic follicle, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans counts also exhibited remarkable changes among groups (P < 0.05). The statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, shown by different letters on the columns. P, primordial follicle; Pr, primary follicle; S, secondary follicle; PA, preantral follicle; A, antral follicle; AF, atretic follicle; CL, corpus luteum; CA, corpus albicans

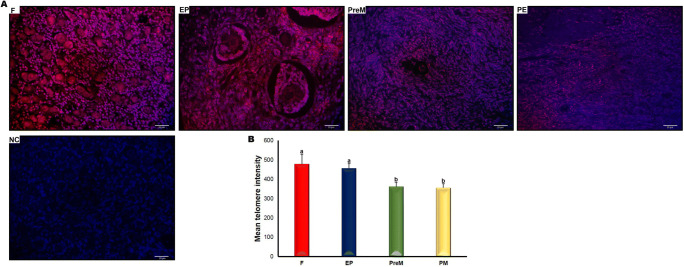

The intensity of telomere signals decreases from fetal to postmenopausal ovaries

We also measured the relative telomere signal intensities across the fetal, early postnatal, premenopausal, and postmenopausal groups. As expected, telomere signals were observed in the nuclei of ovarian cells including oocytes, granulosa cells, and stromal cells (Fig. 2a). We found that the telomere signal intensity gradually decreased across the four groups, from fetal to postmenopausal. Moreover, the fetal and early postnatal groups had significantly higher telomere intensities compared with the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups (Fig. 2b; P < 0.001). In contrast, no considerable differences were observed between the fetal and early postnatal groups or between the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The intensity of telomere signals in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Cellular localization of telomere signals in the ovary groups. As expected, we observed nuclear telomeric signals in the oocytes and granulosa cells, as well as in other ovarian cells. The representative micrographs were captured at × 400 original magnification. The scale bars are equal to 20 μm. Negative control (NC) indicates that the telomeric probe was not included. b The relative telomere intensities in the four ovary groups. The F and EP groups had significantly higher mean telomere intensities compared with the PreM and PM groups (P < 0.001). The statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, shown by different letters on the columns. Statistical significance is indicated by different letters on the columns

TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 expression in human ovaries

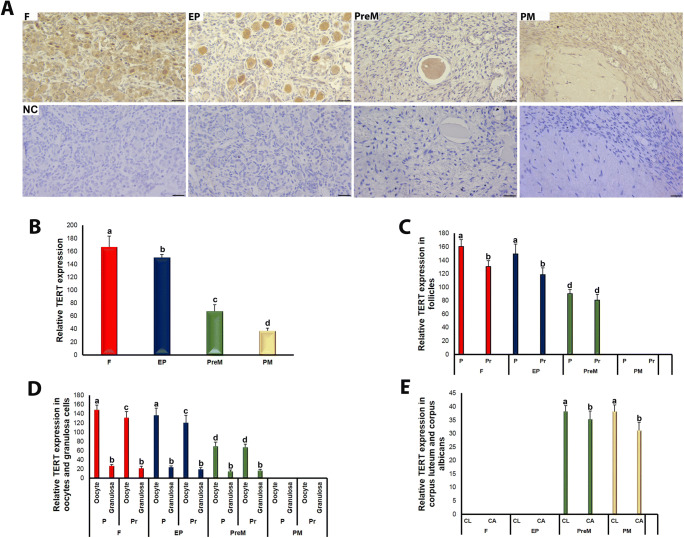

We also analyzed the spatial and temporal expression of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins for each group. TERT expression was detected in the follicles at different development stages, as well as in the stromal cells, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans of the fetal, early postnatal, premenopausal, and postmenopausal groups (Fig. 3a). In the follicles, both oocytes and granulosa cells localized TERT in either their cytoplasmic or nuclear regions. In the oocytes, the nuclei exhibited more intense TERT expression than the cytoplasmic regions. On the contrary, weak cytoplasmic and nuclear TERT expressions were detected in the cells in the stromal area, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans (Fig. 3a). The TERT expression decreased significantly across the four ovary groups, from fetal to postmenopausal (Fig. 3b; P < 0.05). Furthermore, primordial and primary follicles of the fetal and early postnatal groups had higher TERT expression than the same follicle types of the premenopausal group (Fig. 3c; P < 0.05). Also, primordial follicles possessed higher TERT expression than primary follicles in the fetal and early postnatal groups (Fig. 3c; P < 0.05). By contrast, the premenopausal group showed no remarkable difference between its primordial and primary follicles. It is worth noting that primordial and primary follicles were not observed in sufficient numbers and quality in the postmenopausal group; therefore, the TERT and other protein expression analysis could not be performed for this group (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

TERT immunoexpression in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Cellular localization of TERT in the ovary groups. The oocytes and granulosa cells of follicles, other cells in the stromal area, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans expressed TERT in their cytoplasmic and nuclear regions. The negative control (NC) sections presented below each micrograph involved the isotype antibody at the same concentration as the TERT primary antibody and were used to detect any non-specific staining. The relative TERT expression levels in the ovary groups, F to PM, were measured using ImageJ software. The representative micrographs were captured at × 400 original magnification. The scale bars are equal to 50 μm. b The relative TERT expression in the ovary groups. We found that TERT expression gradually and significantly decreased from F to PM groups (P < 0.05). c The relative TERT expression in the primordial and primary follicles of the groups F through PreM. There was a decreasing trend in the TERT expression in both follicles from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). It is noteworthy that we could not observe the follicles in sufficient numbers and quality in the PM group; therefore, TERT expression was not evaluated. d The relative TERT expression in the oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles among groups. The oocytes of primordial and primary follicles of the PM group exhibited lower TERT expression compared with those of the remaining groups (P < 0.05). e The relative TERT expression in the corpus luteum and corpus albicans. Although there were no differences among groups, in the PreM and PM groups, the corpus luteum had higher TERT expression than the corpus albicans (P < 0.05). The statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by different letters on the columns. P, primordial follicles; Pr, primary follicles; CL, corpus luteum; CA, corpus albicans

TERT expression in the oocytes of primordial and primary follicles was lower in the premenopausal group than in the fetal and early postnatal groups (Fig. 3d; P < 0.05). In these latter groups, the oocytes expressed TERT more in primordial follicles than in primary follicles (P < 0.05), but no such significant difference was observed in the premenopausal group (Fig. 3d). Although we did not detect any remarkable variations across the four groups in the TERT expression in the granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles, for follicles of the same type, the TERT expression was lower in the granulosa cells compared with that in the oocytes in the fetal, early postnatal, and premenopausal groups (Fig. 3d; P < 0.05). In the corpus luteum and corpus albicans structures, TERT expression did not differ in the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups; however, we found higher TERT expression in the corpus luteum compared with the corpus albicans of these groups (Fig. 3e; P < 0.05).

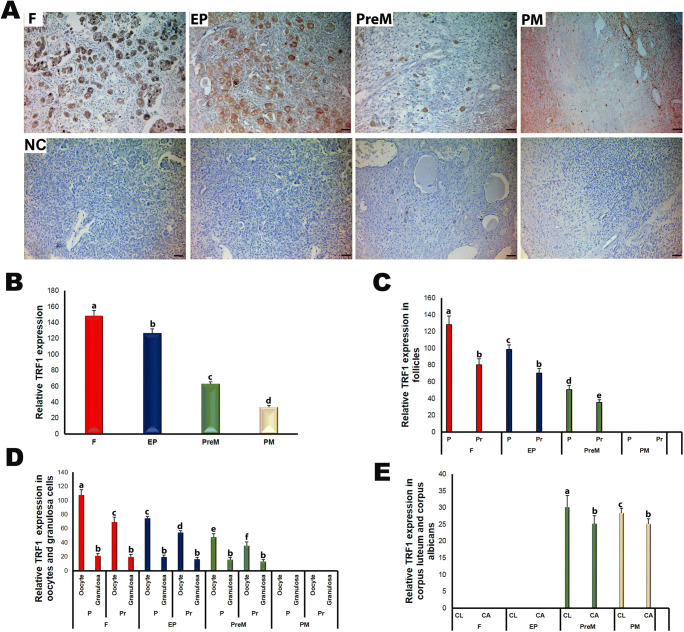

When analyzing TRF1 expression in the ovary groups, we found immunoexpression in the follicles at different development stages and in stromal cells, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans (Fig. 4). The TRF1 expression was stronger in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus in the oocytes and granulosa cells of the follicles, as in the cells located in the stroma, corpus luteum, or corpus albicans (Fig. 4a). The relative TRF1 expression levels decreased significantly and progressively from fetal to postmenopausal groups (Fig. 4b; P < 0.05). Also, TRF1 expression in the primordial follicles gradually decreased from fetal to premenopausal groups (Fig. 4c; P < 0.05). The primary follicles had higher expression in the fetal and early postnatal groups than in the premenopausal group (P < 0.05). Except in the postmenopausal group, primordial follicles exhibited more TRF1 expression compared with primary follicles within each group (Fig. 4c; P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

The immunoexpression of TRF1 in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Cellular localization of TRF1 in the ovary groups. The ovarian cells including oocytes and granulosa cells expressed TRF1 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear regions. The negative control (NC) sections presented below each micrograph involved the isotype antibody at the same concentration as the TRF1 primary antibody and were used to detect any non-specific staining. The relative TRF1 expression in the human ovaries was measured using ImageJ software. b The relative TRF1 expression in the ovary groups. We have detected progressively decreased TRF1 expression levels from F to PM groups (P < 0.05). c The relative TRF1 expression in primordial and primary follicles of the ovary groups. Its expression in the primordial and primary follicles gradually reduced from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). d The relative TRF1 expression in the oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles in the ovary groups. While there were no remarkable changes in TRF1 expression in the granulosa cells across groups, we found a decreasing trend, from F to PreM groups, in the oocytes (P < 0.05). e The relative TRF1 expression in the corpus luteum and corpus albicans. In PreM and PM groups, the corpus luteum had higher TRF1 expression compared with the corpus albicans (P < 0.05). The statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by different letters on the columns. The representative micrographs were captured at × 400 original magnification. It is noteworthy that we did not observe follicles at sufficient numbers and quality in the PM group; therefore, TRF1 expression could not be evaluated. The scale bars are equal to 50 μm. P, primordial follicles; Pr, primary follicles; CL, corpus luteum; CA, corpus albicans

TRF1 expression gradually decreased in the oocytes of primordial and primary follicles in the transition from fetal to premenopausal (Fig. 4d; P < 0.05); however, no such decrease was observed in granulosa cells (Fig. 4d). Additionally, we found that the corpus luteum had higher TRF1 expression in the premenopausal group compared with that in the postmenopausal group (P < 0.05), but no such difference existed for the corpus albicans (Fig. 4e). In both premenopausal and postmenopausal groups, the corpus albicans exhibited lower TRF1 expression than the corpus luteum (P < 0.05).

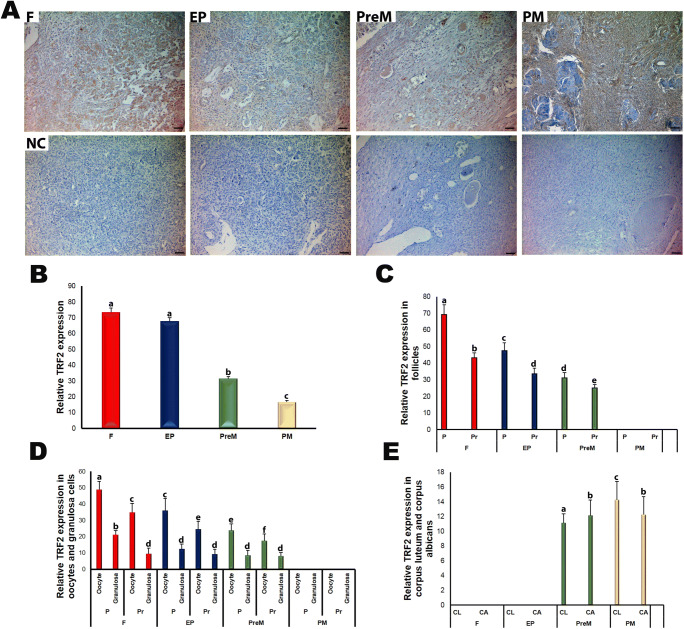

Like the TRF1 expression pattern, we observed TRF2 expression in the follicles at different stages and in certain stromal cells, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans in the ovaries from fetal to postmenopausal groups (Fig. 5a). TRF2 localized either in the nuclear or cytoplasmic regions of the oocytes and granulosa cells of the follicles. In the oocytes, the expression was more intense in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus. The relative TRF2 expression showed a gradual decrease from fetal to postmenopausal groups (Fig. 5b), with the fetal and early postnatal groups demonstrating significantly higher TRF2 expression compared with the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups (P < 0.05). Also, we found higher TRF2 expression in the premenopausal group than in the postmenopausal group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

TRF2 immunoexpression in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Cellular localization of TRF2 in the ovary groups. We observed nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of TRF2 in ovarian cells such as oocytes, granulosa cells, and stromal cells. The negative control (NC) sections presented below each micrograph involved the isotype antibody at the same concentration as the TRF2 primary antibody and were used to detect any non-specific staining. Also, the relative TRF2 expression in the ovary groups was measured using ImageJ software. b The relative TRF2 expression in the ovary groups. The F and EP groups showed significantly higher TRF2 expression levels compared with the PreM and PM groups (P < 0.05). c The relative TRF2 expression in primordial and primary follicles of the ovary groups. Its expression in the primordial and primary follicles gradually decreased from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). d The relative TRF2 expression in the oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles in the ovary groups. Although there were no remarkable changes in the granulosa cells among groups, the TRF2 expression in the oocytes progressively reduced from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). e The relative TRF2 expression in the corpus luteum and corpus albicans. The corpus luteum had lower TRF2 expression in the PreM group compared with that in the PM group (P < 0.05). The statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by different letters on the columns. The representative micrographs were captured at ×400 original magnification. It is worth noting that we did not observe follicles at sufficient numbers and quality in the PM group; therefore, we could not analyze the TRF2 expression. The scale bars are equal to 50 μm. P, primordial follicles; Pr, primary follicles; CL, corpus luteum; CA, corpus albicans

The primordial and primary follicles exhibited progressively decreasing TRF2 expression across the groups, from fetal to premenopausal (Fig. 5c; P < 0.05). In addition, primordial follicles possessed higher expression than primary follicles in each group (P < 0.05). The TRF2 expression in the oocytes of primordial and primary follicles decreased evenly and significantly from fetal to premenopausal groups (Fig. 5d; P < 0.05). Also, we found that the granulosa cells of primordial follicles had remarkably higher expression in the fetal group compared with those in the remaining groups (P < 0.05). Intriguingly, the corpus luteum had lower TRF2 expression in the premenopausal group than in the postmenopausal group (Fig. 5e; P < 0.05). Additionally, the corpus albicans had higher TRF2 expression than the corpus luteum in the premenopausal group; however, the pattern was opposite in the postmenopausal group (P < 0.05).

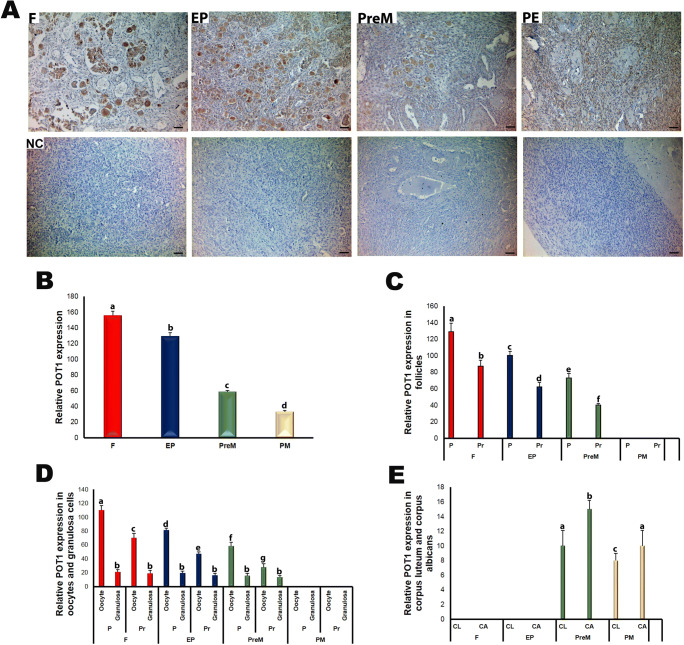

In the human ovaries, POT1 resided in the nuclear and cytoplasmic regions of the oocytes and granulosa cells of the follicles, as well as in the cells of stroma, corpus luteum, and corpus albicans (Fig. 6a). Importantly, across all groups, from fetal to postmenopausal, the oocytes had stronger POT1 expression compared with other ovarian cells. Meanwhile, the POT1 expression progressively and significantly decreased from fetal to postmenopausal groups (Fig. 6b; P < 0.05). Similarly, primordial and primary follicles showed gradually reduced POT1 expression from fetal to premenopausal groups (Fig. 6c; P < 0.05). In all groups, primordial follicles had higher POT1 expression than primary follicles (P < 0.05). Also, in the oocytes of primordial and primary follicles, we observed progressively decreasing POT1 expression from fetal to premenopausal groups (Fig. 6d; P < 0.05). In each group, the oocytes of primordial follicles had higher POT1 expression compared with the oocytes of primary follicles (P < 0.05). By contrast, we did not detect any difference across the four groups for the POT1 expression in the granulosa cells (Fig. 6d). The corpus luteum and corpus albicans structures expressed POT1 at significantly higher levels in the premenopausal group than in the postmenopausal group (Fig. 6e; P < 0.05). Moreover, in each group, POT1 expression levels were higher in the corpus albicans than in the corpus luteum (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

The immunoexpression of POT1 in the fetal (F), early postnatal (EP), premenopausal (PreM), and postmenopausal (PM) ovary groups. a Cellular localization of POT1 in the ovary groups. The POT1 expression in the oocytes was stronger in comparison with that in other ovarian cells in which nuclear and cytoplasmic POT1 expression had similar intensities. The negative control (NC) sections presented below each micrograph involved the isotype antibody at the same concentration as the POT1 primary antibody and were used to detect any non-specific staining. Furthermore, the relative POT1 expression in the human ovaries was analyzed using ImageJ software. b The relative POT1 expression in the ovary groups. It gradually decreased from F to PM groups (P < 0.05). c The relative POT1 expression in primordial and primary follicles of the ovary groups. We documented that POT1 expression levels in the primordial and primary follicles reduced from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). d The relative POT1 expression in the oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles in the ovary groups. Although there were no remarkable changes in the granulosa cells among groups, the POT1 expression in the oocytes of primordial and primary follicles progressively decreased from F to PreM groups (P < 0.05). e The relative POT1 expression in the corpus luteum and corpus albicans. The corpus luteum and corpus albicans had lower expressions in the PreM group compared with those in the PM group (P < 0.05). The statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by different letters on the columns. The representative micrographs were captured at × 400 original magnification. It is worth noting that we did not observe follicles at sufficient numbers and quality in the PM group; therefore, we could not analyze the POT1 expression. The scale bars are equal to 50 μm. P, primordial follicles; Pr, primary follicles; CL, corpus luteum; CA, corpus albicans

Discussion

The present study documents, for the first time, that the intensity of telomere signals progressively reduced and the TERT, TRF1, TFR2, and POT1 expression gradually decreased across the human ovary groups, fetal to postmenopausal, as well as in the follicles and oocytes. The remarkably decreased TERT and telomeric protein levels with ovarian aging may be derived from a progressively reduced number of oocytes or follicles, as reported in a previous study [41], and from decreased expression of these proteins in the granulosa and stromal cells in later life. And the telomere shortening in the ovarian cells such as stromal and luteal cells, in addition to the oocytes and granulosa cells, might contribute to the reduced telomere signal intensities in the premenopausal and postmenopausal groups.

Another potential reason for telomere shortening with aging [42] is the gradual decrease of TERT expression in the human ovaries in later maternal ages. As is known, TERT expression is closely correlated with telomerase activity [12, 43]. To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have focused on TERT expression and telomerase activity in the ovaries of humans or other mammals. One of these studies, Kinugawa et al. (2000), reported that telomerase activity in human ovaries decreased with advancing age, possibly due to follicle depletion [33]. Similarly, telomerase activity, as well as TERT mRNA expression, lessened in the ovarian luteinized granulosa cells as women’s age increased [44]. As expected, the telomerase activity of old cows (151.3 months) was less than of young ones (28.1 months), resulting in telomere shortening in the granulosa cells [45]. Although we could not explore telomerase activity in the current study due to the absence of fresh ovarian tissues, the TERT expression showed a decreasing trend across fetal to postmenopausal groups in the ovaries, follicles, and oocytes, which may have modulated the telomerase activity in a similar manner. Taken together, the gradual decrease of TERT expression in the human ovaries that accompanied aging may be one of the main factors contributing to telomere shortening in the ovarian cells.

The basic function of TRF1 and TRF2 proteins is to maintain the structural integrity and length of telomeres in the eukaryotic cells [46]. Furthermore, these proteins contribute to the formation of the replication fork during DNA synthesis, the attachment of telomeres to the nuclear membrane throughout meiotic and mitotic divisions, and the protection of telomeres from fusion [46]. Derevyanko et al. (2017) revealed that the Trf1 expression decreased with biological aging in mouse and human skin epidermis [47]. Although no study has observed Trf2 expression in oocytes during ovarian aging, TRF2 colocalization with TERT in the nuclear region of human fetal oocytes has been demonstrated [10], as displayed in the human spermatocytes nuclei [48]. In the present study, TRF1 and TRF2 protein expressions gradually decreased from fetal to postmenopausal groups, as well as in the follicles and oocytes. The reduced expression of TRF1 and TRF2 may be associated with the gradual shortening of telomeres in the ovarian cells that coincides with advancing age since these proteins play crucial roles in maintaining telomeric integrity.

Telomere shortening below critical levels seems to be associated with biological aging and cardiovascular and infectious diseases [49–51] as well as with some human syndromes such as dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [52]. In addition, patients with polycystic ovary syndrome had longer [53] and shorter telomere lengths [54] in their granulosa cells compared with the control group. Shortened telomeres were also documented in the granulosa cells from patients having occult ovarian insufficiency [55]. Moreover, Turner et al. (2019) reported that the first polar bodies and blastomeres (obtained from day-3 embryos) of women above 35 years old had significantly shorter telomeres compared with those of younger women [56]. In the same study, no correlation was found between telomere length and age-related aneuploidy in the oocytes and embryos. In our study, we revealed that telomeres progressively shortened as women age. As is known, once telomeres reach a critically short length, not only may cell cycle arrest, genomic instability, and cell death be triggered [57, 58] but also oocyte aging [59–61], abnormal meiotic spindles [62], arrested/fragmented embryos [63], reduced chiasmata and synapsis [64], and infertility [65]. Thus, uncovering the molecular background of telomere attrition and its close relationship with emerging abnormalities may contribute to protecting humans from some diseases/syndromes and age-related fertility loss.

In conclusion, this study is the first to characterize the relative expression levels and cellular localizations of TERT, TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 proteins, as well as telomere signal intensities, in human ovaries that ranged from fetal to postmenopausal. The most prominent limitation of this study was the use of ovarian tissues with suspected pathological changes; thereby, we have to mention that abnormalities such as cystic formations, especially in the pediatric cases, might influence the findings. Despite this limitation, our results indicate that the decreased expression of TERT and telomere-associated proteins may underlie telomere shortening in the ovarian cells, including oocytes and granulosa cells, during maternal aging and, therefore, may be one of the underlying causes of female infertility in older women. The molecular biological mechanism(s) and intracellular signaling pathway(s) regulating the level of telomeric proteins and their functions in human oocytes and granulosa cells should be evaluated to establish the exact relationship with the development of female infertility during aging.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ozlem Okutman (PhD) for helpful comments and corrections on this article.

Authors’ contributions

S.O. and H.S.T. designed the study. F.U. and E.G.K. created the data, and F.U. wrote the article. H.S.T. performed the pathological analysis of the human ovaries. S.O., H.S.T., and E.G.K. reviewed and edited the article.

Funding

This study was supported by TUBITAK (Grant No. 117S258).

Compliance with ethical standards

This human subject research was approved by the Akdeniz University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 662, Date: December 14, 2016).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maciejowski J de Lange T. Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017;18:175-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Diotti R, Loayza D. Shelterin complex and associated factors at human telomeres. Nucleus. 2011;2:119–135. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.2.15135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smogorzewska A, van Steensel B, Bianchi A, Oelmann S, Schaefer MR, Schnapp G, de Lange T. Control of human telomere length by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1659-1668.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilicheva NV, Podgornaya OI, Voronin AP. Telomere repeat-binding factor 2 ıs responsible for the telomere attachment to the nuclear membrane. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2015;101:67–96. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Steensel B, de Lange T. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature. 1997;385:740–743. doi: 10.1038/385740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L, Bailey SM, Okuka M, Munoz P, Li C, Zhou L, et al. Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1436–1441. doi: 10.1038/ncb1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broccoli D, Chong L, Oelmann S, Fernald AA, Marziliano N, van Steensel B, Kipling D, le Beau MM, de Lange T. Comparison of the human and mouse genes encoding the telomeric protein, TRF1: chromosomal localization, expression and conserved protein domains. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:69–76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pochukalina GN, Ilicheva NV, Podgornaya OI, Voronin AP. Nucleolus-like body of mouse oocytes contains lamin A and B and TRF2 but not actin and topo II. Mol Cytogenet. 2016;9:50. doi: 10.1186/s13039-016-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reig-Viader R, Brieno-Enriquez MA, Khoriauli L, Toran N, Cabero L, Giulotto E, et al. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA and telomerase in human fetal oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:414–422. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448:1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozturk S, Sozen B, Demir N. Telomere length and telomerase activity during oocyte maturation and early embryo development in mammalian species. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:15–30. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, Multani AS, He H, Cosme-Blanco W, Deng Y, Deng JM, Bachilo O, Pathak S, Tahara H, Bailey SM, Deng Y, Behringer RR, Chang S. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churikov D, Wei C, Price CM. Vertebrate POT1 restricts G-overhang length and prevents activation of a telomeric DNA damage checkpoint but is dispensable for overhang protection. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6971–6982. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01011-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosokawa K, MacArthur BD, Ikushima YM, Toyama H, Masuhiro Y, Hanazawa S, et al. The telomere binding protein Pot1 maintains haematopoietic stem cell activity with age. Nat Commun. 2017;8:804. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00935-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinzaru AM, Hom RA, Beal A, Phillips AF, Ni E, Cardozo T, Nair N, Choi J, Wuttke DS, Sfeir A, Denchi EL. Telomere replication stress ınduced by POT1 ınactivation accelerates tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2170–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner CA, Wolny YM, Adler RR, Cohen J. Alternative splicing of the telomerase catalytic subunit in human oocytes and embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:845–850. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.9.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russo V, Berardinelli P, Martelli A, Di Giacinto O, Nardinocchi D, Fantasia D, et al. Expression of telomerase reverse transcriptase subunit (TERT) and telomere sizing in pig ovarian follicles. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:443–455. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6603.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dundee JA, Esfandiari N, Blanchette Porter MM, McGee E. Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) is stage specific in the ovarian follicle. ASRM. 2015;104(Supplement):e134. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright DL, Jones EL, Mayer JF, Oehninger S, Gibbons WE, Lanzendorf SE. Characterization of telomerase activity in the human oocyte and preimplantation embryo. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:947–955. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner S, Wong HP, Rai J, Hartshorne GM. Telomere lengths in human oocytes, cleavage stage embryos and blastocysts. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:685–694. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosden RG, Laing SC, Felicio LS, Nelson JF, Finch CE. Imminent oocyte exhaustion and reduced follicular recruitment mark the transition to acyclicity in aging C57BL/6J mice. Biol Reprod. 1983;28:255–260. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod28.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen MP, Sternfeld B, Schuh-Huerta SM, Reijo Pera RA, McCulloch CE, Cedars MI. Antral follicle count: absence of significant midlife decline. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2182–2185. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarin JJ, Perez-Albala S, Cano A. Cellular and morphological traits of oocytes retrieved from aging mice after exogenous ovarian stimulation. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:141–150. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Vogt E, Yin H, Gosden R. Spindles, mitochondria and redox potential in ageing oocytes. Reprod BioMed Online. 2004;8:45–58. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60497-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bruin JP, Dorland M, Spek ER, Posthuma G, van Haaften M, Looman CW, et al. Age-related changes in the ultrastructure of the resting follicle pool in human ovaries. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:419–424. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.015784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson JF, Felicio LS, Osterburg HH, Finch CE. Altered profiles of estradiol and progesterone associated with prolonged estrous cycles and persistent vaginal cornification in aging C57BL/6J mice. Biol Reprod. 1981;24:784–794. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod24.4.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flurkey K, Gee DM, Sinha YN, Wisner JR, Jr. Finch CE. Age effects on luteinizing hormone, progesterone and prolactin in proestrous and acyclic C57BL/6j mice. Biol Reprod. 1982;26:835–846. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod26.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May-Panloup P, Boucret L, de la Barca JM C, Desquiret-Dumas V, Ferre-L’Hotellier V, Moriniere C, et al. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:725–743. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navot D, Drews MR, Bergh PA, Guzman I, Karstaedt A, Scott RT, Jr, Garrisi GJ, Hofmann GE. Age-related decline in female fertility is not due to diminished capacity of the uterus to sustain embryo implantation. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasilopoulos E, Fragkiadaki P, Kalliora C, Fragou D, Docea AO, Vakonaki E, et al. The association of female and male infertility with telomere length (review) Int J Mol Med. 2019;44:375–389. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalmbach KH, Fontes Antunes DM, Dracxler RC, Knier TW, Seth-Smith ML, Wang F, Liu L, Keefe DL. Telomeres and human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinugawa C, Murakami T, Okamura K, Yajima A. Telomerase activity in normal ovaries and premature ovarian failure. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2000;190:231–238. doi: 10.1620/tjem.190.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozturk S, Sozen B, Demir N. Epab and Pabpc1 are differentially expressed in the postnatal mouse ovaries. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:137–146. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehlmann LM, Saeki Y, Tanaka S, Brennan TJ, Evsikov AV, Pendola FL, Knowles BB, Eppig JJ, Jaffe LA. The Gs-linked receptor GPR3 maintains meiotic arrest in mammalian oocytes. Science. 2004;306:1947–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.1103974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uysal F, Akkoyunlu G Ozturk S. Decreased expression of DNA methyltransferases in the testes of patients with non-obstructive azoospermia leads to changes in global DNA methylation levels. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Uysal F, Ozturk S, Akkoyunlu G. Superovulation alters DNA methyltransferase protein expression in mouse oocytes and early embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1087-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aida J, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, Nakamura K, Ishikawa N, Terai M, Matsuda Y, Aida S, Arai T, Takubo K. Determination of telomere length by the quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) method. Am J Anal Chem. 2014;5:775–783. [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Sullivan JN, Finley JC, Risques RA, Shen WT, Gollahon KA, Moskovitz AH, et al. Telomere length assessment in tissue sections by quantitative FISH: image analysis algorithms. Cytometry A. 2004;58:120–131. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosebent EG, Uysal F, Ozturk S. The altered expression of telomerase components and telomere-linked proteins may associate with ovarian aging in mouse. Exp Gerontol. 2020;110975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:465–493. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalmbach KH, Antunes DM, Kohlrausch F, Keefe DL. Telomeres and female reproductive aging. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33:389–395. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1567823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu A, Ichihashi M, Ueda M. Correlation of the expression of human telomerase subunits with telomerase activity in normal skin and skin tumors. Cancer. 1999;86:2038–2044. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991115)86:10<2038::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu W, Zhu GJ. Expression of telomerase in human ovarian luteinized granulosa cells and its relationship to ovarian function. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2003;38:402–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goto H, Iwata H, Takeo S, Nisinosono K, Murakami S, Monji Y, Kuwayama T. Effect of bovine age on the proliferative activity, global DNA methylation, relative telomere length and telomerase activity of granulosa cells. Zygote. 2013;21:256–264. doi: 10.1017/S0967199411000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Tu Z, Liu C, Liu H, Kaldis P, Chen Z, Li W. Dual roles of TRF1 in tethering telomeres to the nuclear envelope and protecting them from fusion during meiosis. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:1174–1188. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derevyanko A, Whittemore K, Schneider RP, Jimenez V, Bosch F, Blasco MA. Gene therapy with the TRF1 telomere gene rescues decreased TRF1 levels with aging and prolongs mouse health span. Aging Cell. 2017;16:1353–1368. doi: 10.1111/acel.12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reig-Viader R, Vila-Cejudo M, Vitelli V, Busca R, Sabate M, Giulotto E, et al. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) and telomerase are components of telomeres during mammalian gametogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:103. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.116954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh H, Wang SC, Prahash A, Sano M, Moravec CS, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Youker KA, Entman ML, Schneider MD. Telomere attrition and Chk2 activation in human heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5378–5383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Sullivan JN, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA, Finley JC, Shen WT, Emerson S, et al. Chromosomal instability in ulcerative colitis is related to telomere shortening. Nat Genet. 2002;32:280–284. doi: 10.1038/ng989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiemann SU, Satyanarayana A, Tsahuridu M, Tillmann HL, Zender L, Klempnauer J, et al. Hepatocyte telomere shortening and senescence are general markers of human liver cirrhosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:935–942. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0977com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:640–649. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei D, Xie J, Yin B, Hao H, Song X, Liu Q, Zhang C, Sun Y. Significantly lengthened telomere in granulosa cells from women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:861–866. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0945-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, Deng B, Ouyang N, Yuan P, Zheng L, Wang W. Telomere length is short in PCOS and oral contraceptive does not affect the telomerase activity in granulosa cells of patients with PCOS. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:849–859. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0929-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butts S, Riethman H, Ratcliffe S, Shaunik A, Coutifaris C, Barnhart K. Correlation of telomere length and telomerase activity with occult ovarian insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4835–4843. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner K, Lynch C, Rouse H, Vasu V, Griffin DK. Direct single-cell analysis of human polar bodies and cleavage-stage embryos reveals no evidence of the telomere theory of reproductive ageing in relation to aneuploidy generation. Cells. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Herbig U, Jobling WA, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Sedivy JM. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21(CIP1), but not p16(INK4a) Mol Cell. 2004;14:501–513. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herbig U, Sedivy JM. Regulation of growth arrest in senescence: telomere damage is not the end of the story. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keefe DL, Liu L. Telomeres and reproductive aging. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:10–14. doi: 10.1071/rd08229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keefe DL. Telomeres and meiosis in health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:115–116. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6462-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keefe DL, Marquard K, Liu L. The telomere theory of reproductive senescence in women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:280–285. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000193019.05686.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu L, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Requirement of functional telomeres for metaphase chromosome alignments and integrity of meiotic spindles. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:230–234. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keefe DL, Franco S, Liu L, Trimarchi J, Cao B, Weitzen S, Agarwal S, Blasco MA. Telomere length predicts embryo fragmentation after in vitro fertilization in women--toward a telomere theory of reproductive aging in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1256–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu L, Franco S, Spyropoulos B, Moens PB, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Irregular telomeres impair meiotic synapsis and recombination in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6496–6501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400755101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, 2nd, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]