Abstract

This paper aims to examine the association between the consumer’s socioeconomic status and the consumption of organic food. A conceptual model developed in this paper provides a more detailed understating of how socioeconomic status can, through the perceived values of organic food, influence the willingness to buy and to pay. A sample of 384 consumers of organic food in Tunisia were interviewed using convenience sampling. The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses of the proposed conceptual model. The socioeconomic status of consumers (education, occupation and income) was found to be an important predictor of perceived organic food values (utilitarian and hedonic). While utilitarian value had a stronger influence on the willingness to pay, hedonic value proved more influential on the willingness to buy. This paper is one of the earliest studies of its kind, which focused on the association between socioeconomic status and organic consumption. Findings have provided clear ways for practitioners to segment their markets on the basis of the socioeconomic status of consumers.

Keywords: SES, Utilitarian value, Hedonic value, Willingness to buy, Willingness to pay, Organic food

Introduction

Researchers in the field of health devoted much attention to the concepts of socioeconomic status of consumer (SES), social class and socioeconomic position (El-Gilany et al. 2012). The assessment of SES was often found to be a major determinant of health and nutritional status as well as of mortality and morbidity (Ghosh and Ghosh 2009). Hence, socioeconomic disparity in nutrition was considered a crucial indicator in accounting for some of the observed social inequalities in health (Alkerwi et al. 2015; Groth et al. 2001). From the perspective of marketing, scholars have typically used SES as a ‘segmentation basis or as a background variable’ (Yoon and Kim 2017). Indeed, people with high socioeconomic status are more likely to consume healthy and nutritious food. People with low SES, however, are more likely to consume nutrition-poor food, which is less consistent with health guidance and nutritional recommendations (Alkerwi et al. 2015; Baumann et al. 2017). This can be explained by the fact that fresh, organic and safe products often have a higher price tag and might not be accessible (Darmon and Drewnowski 2008).

Socioeconomic status is often operationalized by researchers in marketing through three indicators such as income, education, and occupation (Aggarwal et al. 2005; El-Gilany et al. 2012; González et al. 2016). According to Curl et al. (2013), higher education and an increased income correlate with healthy consumption. However, a lower degree of education, which is generally linked with a low-status occupation, tends to correlate with a higher occurrence of low health consciousness and unhealthy behaviors like purchasing conventional food products and smoking combined with a low occurrence of physical activities (Costa et al. 2019; Kranjac et al. 2017).

According to the American Department of Agriculture (2015), agricultural products are certified as organic if ‘they are produced/processed through methods that promote ecological balance, biodiversity and without using growth hormones and pesticides’. Therefore, organic food is considered to be a healthy, nutritious, tasty, fresh and pure type of food (Ditlevsen et al. 2019; Ghali and Toukabri 2019), and its consumption interests the consumers who have a more acute consciousness of their health and their environment (Maehle et al. 2015; Singh and Verma 2017). These are consumers who perceive the superior values of organic food compared with its conventional counterparts. Several previous studies have classified these values into two types: utilitarian values and hedonic values. The former refer to the nutritious, healthfulness, purity and safety attributes of the product, while the latter refer to the better taste, freshness, and pleasure felt when doing something right for one’s health and wellbeing (Anastasiou et al. 2017; Ginon et al. 2014). These values are of more interest to the consumers who enjoy a high socio-economic status (Baumann et al. 2017; Curl et al. 2013). This is because organic food is highly priced compared with its conventional counterpart (Ghali and Toukabri 2019; Wang et al. 2019). Indeed, studies found that consumers who are less sensitive to price are more likely to purchase organic food (Ginon et al. 2014). These are essentially consumers who have a high income (Govidnasamy and Italia 1990; Loureiro et al. 2001) and are more conscious about their health (Ditlevsen et al. 2019; Ghali 2019). Other scholars (Altarawneh 2013; Padel and Foster 2005) found a strong correlation between increasing organic food consumption and levels of formal education, occupation, marital status, income, desire, promotion, quality and health consciousness.

After an extensive search of academic databases devoted to organic consumption, we found that multiple studies focused on several factors that can influence consumer behavior toward organic consumption, like sensitivity to price, availability of products, knowledge, health consciousness, awareness, etc. (Padel and Foster 2005; Ryu et al. 2010; Ghali 2019). More recent studies examined the impact of one or more of SES’ indicators (income, occupation, and education) in several contexts on consumer intention and behavior towards organic food (Costa et al. 2019; Shalev and Morwitz 2012). However, the examination of the association between the level of SES as a whole and organic food consumption is still limited (Pechey and Monsivais 2016). Moreover, there is still a lot to do in the study of the relationship between SES and the positive attitude that can be expressed by the willingness to buy and pay for organic food in the context of organic consumption (Liu et al. 2019). This paper has been conceived to shed light on the association between SES and the consumer’s willingness to buy and pay for organic food through the mediation of perceived values. Hence, the first objective of this study is to test the impact of SES on organic food perceived values, which the present study categorized into utilitarian values and hedonic values. The second objective is to test the influence of organic food perceived values on the consumer’s willingness to pay and to buy. The findings of this study might provide significant insights for practitioners to segment their markets based on the level of SES of their customers, and adapt their marketing strategies based on the specificities of every segment.

Literature review

Socioeconomic status (SES) and perception of organic food

Socioeconomic status (SES) is defined as ‘an individual's or group's position within a hierarchical social structure’ (Lantos 2015). It reflects an individual's social, physical and cultural environment (Pechey and Monsivais 2016). For marketers, SES equally affects the individual’s health directly and can cause health inequalities as long as it significantly influences the individual’s psychology, and affects both health and well-being (Costa et al. 2019; Molarius et al. 2007). From this perspective, the latest studies (Ann and Walsh 2020; Batat et al. 2017) stated that stable employment, which is correlated with adequate income, is vital to preserve the households’ health through the consumption of pure and nutritious food products. However, these products are not often available for households suffering a low income and an instable occupation (Curl et al. 2013). Therefore, socioeconomic status may exert either a positive or a negative force in a person’s life (Baumann et al. 2017).

In relation to organic food consumption, several studies stated that higher income households buy organic products more frequently than lower income households (Govidnasamy and Italia 1990; Loureiro et al. 2001). From their side, Curl et al. (2013) found a strong correlation between an increasing consumption of organic food and levels of formal education. Based on earlier evidence (Alkerwi et al. 2015; Curl et al. 2013), individuals with a high level of education and income are more aware of food hazards and intent on purchasing food, which they perceive as more wholesome and nutritious, purer and safer. Additional studies (Padel and Foster 2005 and Shahar et al. 2005) found that regular consumers of organic food tend to be educated, affluent and belonging to higher social classes. They are consumers who are more likely to perceive the superior values of organic food (tastiness, freshness, helpfulness, purity, etc.) compared with its conventional counterparts. In this context, Batat et al. (2017) stated that the difference in SES leads to difference in social classes in terms of food safety and nutrition intakes. Hence, low SES consumers are more likely to consume energy-rich but nutrition-poor food due to the fact that local, fresh, organic products are often premium priced and might not be accessible (Darmon and Drewnowski 2008). Relying on this literature review, it can then be drawn that consumers with a higher socioeconomic status are more likely to pay premium prices and purchase organic food as long as they perceive it as healthy, nutritious, pure, fresh and tasty. As we previously mentioned, these multiple values of organic food are categorized into utilitarian and hedonic values (Fuljahn and Moosmayer 2011; Ditlevsen et al. 2019). Therefore, the following hypotheses can be formulated:

H1.a. Consumer’s socioeconomic status will have a significant positive effect on organic food perceived utilitarian value.

H1.a. Consumer’s socioeconomic status will have a significant positive effect on organic food perceived hedonic value.

Organic food perceived values and consumer willingness to buy and to pay

Utilitarian value and willingness to buy and pay for organic food

Willingness to buy (WTB) and willingness to pay (WTP) are considered two constructs, which are surrogates of purchase intention and are indicators of actual purchase behavior (Lio and Hsieh 2013).

WTB refers to the consumer’s likelihood to purchase a product and recommend it to others (Ghali 2019). It is strongly correlated to actual behavior as long as it expresses the consumer preference toward a special product (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980). Thus, it is derived from a positive attitude towards the product and refers to the effort made by the consumer in order to purchase the product. WTP is another measure of consumer preference for a special product (Anastasiou et al. 2017). It refers to the consumer’s reaction toward the product’s price and an alternative to price elasticity (Alphonce and Alfnes 2017). Thus, WTP is also positively correlated with behavioral attitude (Nassivera et al. 2017).

In the field of organic food farming, a previous large amount of evidence showed that the higher prices of organic food products are often considered to be the greatest constraint hindering the further expansion of the organic food market (Petljak et al. 2017). However, many consumers are ready to pay premium prices for organic food when they compare its utilitarian values (high nutritious quality, healthfulness, freshness, purity, etc.) with those of its conventional counterpart (Anastasiou et al. 2017; Petljak et al. 2017; Aryal et al. 2009). Hence, they justify their willingness to buy and to pay for organic food by the cost of investment in good health, welfare and environment-friendliness. Following this literature review, we can state the following hypotheses:

H2.a. The utilitarian value of organic food will have a significant positive effect on the consumers’ willingness to buy.

H2.b. The utilitarian value organic food will have a significant positive effect on the consumers’ willingness to pay.

Hedonic value and willingness to buy and pay for organic food

The hedonic value of an organic food product refers to the better taste and the enjoyable experience felt by the consumer when consuming a product beneficial for health and the environment (Babin et al. 1994). It also expresses the self-rewarding feelings of doing the right thing for one’s health and wellbeing (Arvola et al. 2008 and Lim et al. 2014). In this context, Singh and Verma (2017) stated that the different hedonic attributes of an organic food product, like taste, freshness, appearance and other sensory characteristics, influence consumer preferences towards organic produce, and consequently foster the intention to buy. These authors argued that the positive emotions felt during the consumption of nutritious food strengthen the consumer’s willingness to buy. Additionally, Wang et al. (2019) and Liu et al. (2019) stated that the pleasure and enjoyment that the consumer feels when consuming organic food and his interest in good health and clean environment account for his willingness to pay a premium price. However, despite the positive correlation between both values of organic food (utilitarian vs. hedonic) and WTP, the intensity of this correlation is not always similar for these two values (Lee and Yun 2015). For example, Maehele et al. (2015) found that the differences in the motivation behind the purchase of hedonic vs. utilitarian products define the price, which is then relatively more important for utilitarian products than for hedonic ones. As for Ginon et al. (2014), they argued that consumers are less price-sensitive when making a hedonic purchase. Based on this literature review, the following hypotheses can be formulated:

H3.a. The hedonic value of organic food will have a significant positive effect on the consumer’s willingness to buy.

H3.b. The hedonic value of organic food will have a significant positive effect on the consumer’s willingness to pay.

Methodology

Data collection

The research data were collected via online survey, which was sent to a large sample of customers from May 11, 2020 to June 4, 2020. Two channels were used to collect data. First, the survey was sent by email and social media to the ‘friends’ that we have on these networks. Second, the managers of two supermarkets, which commercialize organic foods, agreed to participate and distribute the survey to their subscriber base.

Two filter questions were asked in the beginning of questionnaire in order to know whether the customer has already purchased organic food and over the age of 20 years ‘since this sample group was able to make organic decisions’ (Teng and Lu 2016). If the respondent did not meet these criteria, the questionnaire was not given. A total of 384 questionnaires were considered. The sample consisted of respondents between the age 20 and 77, almost 58% of them were female.

Results

Measures

Socioeconomic status (SES) construct was measured as a composite of education, income and occupational rank. These three indicators were often used by previous studies and confirmed their validities in different contexts (Gonzalez et al. 2016; White and Tong 2019). Education was measured as the level of formal schooling completed (Gonzalez et al. 2016). The respondents were allowed to choose between four categories ranging from elementary (= 1) to postgraduate (= 4). Almost 72% of the sample had university qualifications. For the monthly personal income, respondents were allowed to choose between six categories ranging from very low income (1 = less than 150 USD) to very high (6 = more than 1500 USD). Just over 68% of the sample considered that they have above of the average monthly income (Ghali 2019). Similarly for the occupation, respondents were allowed to choose between four hierarchical categories ranging from student (1 = rank 1) to senior managers (4 = rank 4). We used the classification of White and Tong (2019) while defining and interpreting the occupational hierarchy. Over 66% of respondents held professional positions and senior managers, 23% were in trade professions and 11% of the sample were students.

The SES indicators (education, income, occupation) were subjected to Categorical Principal Components Analysis via SPSS software following the approach of White and Tong (2019). This method is considered appropriate since the objective here is to assess the components of SES while maximizing the amount of variance accounted for them. The Eigenvalues of the three indicators have met the recommended cut-off levels (1). They accounted for 73% of total scale variance. Their loadings were respectively 0.733, 0.849 and 0.813, which were considered excellent according to White and Tong (2019). Therefore, the three indicators were used to form a single latent SES construct.

Four items were considered to measure the construct of ‘utilitarian perceived value’ of organic food and these were drawn from reputable and reliable study of Ryu et al. (2010). The alpha coefficient for these four items was 0.82. Six items were used to measure the construct of ‘hedonic perceived value’ of organic food, which was extracted from the study of Arvola et al. (2008). These items had a coefficient alpha of 0.77. Three items were used to measure the construct of ‘willingness to buy’ that were drawn from reputable and reliable sources (Dodds et al. 1991; Sweeney et al. 1999). These items produced an alpha coefficient of 0.79. Finally, three items were used to measure the construct ‘willingness to pay’ that were extracted from the reliable studies of Lee et al. (2015) and Netemeyer et al. (2004). They produced an alpha coefficient of 0.84. Hence, for all scales of measurement used in this study, the alpha coefficients exceeded the recommended level and showed good reliability (Fornell and Larcker 1981). All scales were accompanied by 5-point interval scales and item statements can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Standardized loading and reliabilities

| Construct | Items | Loading | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV | U1 | Buying organic food was convenient | 0.869 | 0.863 | 0.887 |

| U2 | Buying organic food was pragmatic and economical | 0.779 | |||

| U3 | It was not a waste of money when buying organic food | 0.834 | |||

| U4 | Buying organic food is interesting | 0.882 | |||

| HV | H1 | Buying organic food would give me pleasure | 0.766 | 0.824 | 0.873 |

| H2 | Buying organic food would feel like doing the morally right thing | 0.774 | |||

| H3 | Buying organic food would make me feel like a better person | 0.828 | |||

| H4 | The use of organic food can affect my well-being positively | 0.847 | |||

| H5 | I would enjoy using organic food | 0.793 | |||

| H6 | I would feel relaxed using organic food | 0.765 | |||

| WTB | WB1 | I consider buying organic food | 0.759 | 0.798 | 0.785 |

| WB2 | I will purchase organic food | 0.846 | |||

| WB3 | There is a strong likelihood that I will buy organic food | 0.769 | |||

| WTP | WP1 | I am willing to spend extra in order to buy organic food | 0.764 | 0.733 | 0.608 |

| WP2 | It is acceptable to pay a premium to purchase organic food | 0.674 | |||

| WP3 | I am willing to pay more for organic food | 0.689 |

Note UT: Utilitarian value; HV; Hedonic value; WTB: willingness to buy; WTP: willingness to pay; CR: Composite reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted

Measurement model

In order to analyze the collected data and examine the model, the two-step Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was applied using the software LISREL 9.10. In the first step, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the measurement model to ensure the reliability and the validity of the measurement model. Then, the final revised constructs in the measurement model were used to form the structure model and test the hypotheses.

In order to test the indirect effects (between SES and WTP and WTB), bootstrapped confidence intervals were used. The average of AVE (Average Variance Extracted) for each latent variable, and factor loadings were employed to assess the convergent validity of the measurement scales (Baggozzi and Yi 1988). The square root of the AVE would assess discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Based on the findings of this study, factor loadings were ranged from 0.674 to 0.882 and AVEs evolved from 0.608 and 0.887, which met the recommended values 0.65 and 0.5 respectively (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Composite reliability values (CR) evolved from 0.733 to 0.863, which exceeded the recommended level. Based on these results, the convergent validity was confirmed for the measurement scale of every variable. The discriminant validity, which indicates the extent to which a certain construct is different from other constructs, was achieved since the square root of AVE for all constructs exceeded the amount of its correlation with other constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The convergent and discriminant validity results were outlined in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively. Additionally, the measurement model fit the collected data well, as all of the tested fit indices were within the acceptable ranges (χ2 = 898; df = 342; χ2/df = 625; GFI = 0.942; AGFI = 0.901; RMSEA = 0.011; CFI = 0.912; PNFI = 0.322).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for discriminant validity

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | − | ||||

| UV | .623 | .941 | |||

| HV | .338 | .087* | .934 | ||

| WTB | .064* | .693 | .634 | .886 | |

| WTP | .067* | .634 | .511 | .045* | .779 |

Note N = 384; * Non- significant at p ≤ 0.05. The square root of AVE is shown as bold at diagonal

Overall, the fit indices, reliability and validity measures suggest that the proposed conceptual model of the study fits the collected data well. Thus, we proceed to examine the structural model.

Structural model

A structural model was assessed in order to test the hypotheses of the research.

First, we examined the fit of structural model. The main values found were χ2 (258) = 1047.382; p < 0.01; χ2/df = 4.059; GFI = 0.928; AGFI = 0.902; TLI = . 933; CFI = 0.901. IFI = 0.923; RMSEA = 0.024. These values were within the recommended tolerable levels (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Therefore, the overall structural model presented good adjustment.

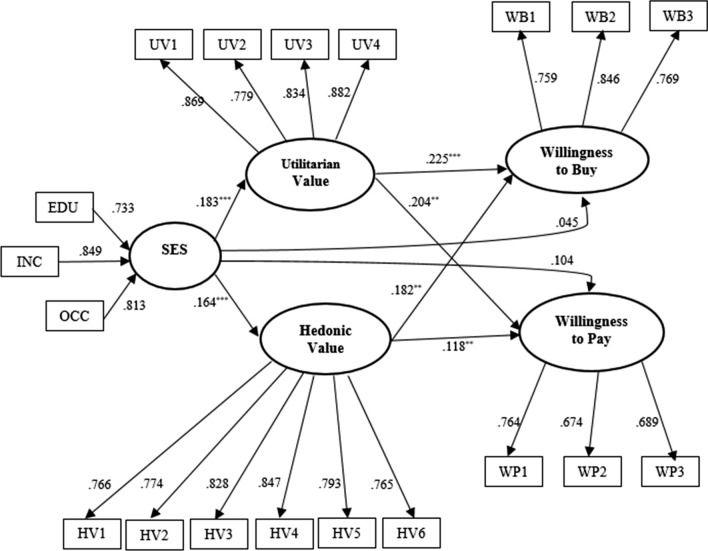

Second, we estimated the direct effects between latent variables of the conceptual model. The path coefficients found indicate that SES had positive significant effect on both utilitarian and hedonic for the respective values (β = 0.183, t-value = 5.287; p < 0.05) and (β = 0.164, t-value = 3.534; p < 0.05). Therefore, H1a and H1b were supported. These results are in accordance with Baumann et al. (2017), Costa et al. (2019) and Curl et al. (2013) who showed the positive association between the level of SES and the diverse values of the healthy consumption. For the variable utilitarian perceived value, the findings indicated that it had significant positive effects on both WTB and WTP for the respective values (β = 0.225, t-value = 5.729; p < 0.05; β = 0.204, t-value = 2.518; p < 0.01). Therefore, H2.a and H2.b were supported. For the variable hedonic perceived value, the path coefficients found indicated that they also had significant positive effects on both WTB and WTP for the respective values (β = 0.182, t-value = 14.463, p < 0.01; β = 0.118, t-value = 4.333, p < 0.01). Therefore, H3.a and H3.b were also supported. These findings showed that perceived values of organic food constituted interesting predictors of WTB and WTP, which were in accordance with several previous studies like Lu and Chi (2018) and Aryal et al. (2009). The direct effects of SES on WTB and WTP were also assessed. The findings indicated non-significant effects for both (β = 0.045, t-value = 1.203; p > 0.05) and (β = 0.104, t-value = 1.133; p > 0.05). This means that the consumers were not welling to buy and to pay for organic food before being aware of its values (Curl et al. 2013; Govidnasamy and Italia 1990).

Third, the mediation of perceived values between SES and WTB and WTP were assessed through the bootstrap procedure following the approach of González et al. (2016) and White and Tong (2019). The standardized indirect effects, the standard errors, and Bias-Corrected Confidence Intervals (BC CIs) were used to assess the significance of mediation of perceived values between SES and WTB and WTP. For the indirect effects of SES on WTB, the bootstrapped confidence interval levels showed that there were significant indirect effects through both utilitarian values (standardized indirect effects = 0.084, p < 0.05; 95%, BC CI 0.170; 0.123) and hedonic values (standardized indirect effects = 0.113, p < 0.01; 95%, BC CI, 0.190, 0.137). This indicated that SES effects WTB through the organic food perceived values. Hence, the consumers were not willing to buy an organic food before being aware of its utilitarian and hedonic values. Similarly, for the indirect effects between SES and WTP, the findings were significant for both utilitarian values (standardized indirect effects = 0.098, p < 0.05; 95%, BC CI 0.180; 0.133) and for hedonic values (standardized indirect effects = 0.112, p < 0.05; 95%, BC CI 0.160; 0.113). These findings indicated that the willingness to pay the premium price of organic food derived mainly from the utilitarian and hedonic perceived values that the consumer perceive. The results of measurement and structural analyses were presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized conceptual model

Discussion

Based on the findings of this study, SES had a positive influence on the perceived values of organic food. The latter were classified into two types: utilitarian values and hedonic values. In the present study, SES was operationalized through three indicators: education, income and occupation of consumers. These findings mean that when the consumer has a high-level SES, he has a more acute perception of the values of organic food and, consequently, he is more willing to consume it. Hence, these findings allowed us to determine the profile of the organic food consumer in Tunisia. He is generally a consumer who has a high education and/or income and/or occupation. These results are in line with those of Alkerwi et al. (2015), Groth et al. 2001 and Kranjac et al. (2017). In this same context, Baumann et al. (2017) argued that low-SES groups perceive healthy food products as being simply out of reach. Darman and Drewnowski (2008), on their side, found that low-SES consumers have low motivation for and knowledge of the nutritional quality of diet. However, based on a survey which involved about 1000 US adults, Zepeda and Li (2007) stated that organic food consumption was found to be directly associated with the availability of this type of food rather than with socioeconomic variables. In the field of arts (music), White and Tong (2019) who did not find any direct links between SES and utilitarian and hedonic attitudes, stressed the mediation of consumer needs. Therefore, relying on the findings of previous research works, we can say that inconsistent findings have cautioned us against using socioeconomic data for understanding consumer behavior. The controversy can only continue over this issue (White and Tong 2019). Our paper comes to support the studies, which confirmed the positive direct link between SES and the consumption of organic food. We showed that when the consumer has a high level of SES he is more likely to perceive the superior values of organic food, a fact that is translated through his willingness to buy and to pay. This direct link between SES and perceived values can be explained by the fact that consumers with a high level of SES are more aware of the benefits of organic food (Baumann et al. 2017) and less sensitive to its premium price (Ghali and Toukabri 2019). Low-SES consumers, on the other hand, consider organic food a “luxury” food that only exists for rich consumers (Ghali 2019). Our survey was conducted in a developing country where organic consumption is at a nascent stage. Organic food products are not available in all supermarkets and groceries, especially in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and they are too expensive in comparison with their conventional counterparts (Ghali 2019). These factors might be accounted for, on the one hand, by lack of knowledge about the healthy and nutritious quality of this product. On the other hand, they might result from the lack of familiarization with and accessibility to organic food. In addition, SES has not proved to have a significant direct influence on WTB and WTB. This means that high-level SES consumers are not able to purchase organic food products before knowing their superior values for health and well-being (Baumann et al. 2017). Therefore, not all consumers having a high SES level are intent on consuming organically. Being aware of the values of organic food was found to be mandatory in eliciting the preference of consumers towards this type of food.

Implications and limitations

From a theoretical perspective, the present study brings several interesting contributions. Indeed, this paper is among the earliest of its kind to focus on the association between SES and organic food consumption from a marketing perspective. In fact, most of the previous research works about SES have been developed from a medical perspective that mainly focused on the relationship between SES and the benefits of healthy and nutritious consumption (Costa et al. 2019; El-Gilany et al. 2012; Pechey and Monsivais 2016). Additional studies have tested the association between SES and consumer behavior in developed markets (Baumann et al., in Canada; Curl et al. 2013 in USA; Groth et al. 2001 in Denmark). However, the present study is among the rare research works to focus on the influence of SES on organic consumption in the context of a developing market (Tunisia), where organic consumption is still, generally, at a nascent stage and where consumers do not have a sufficient knowledge of the benefits of organic food (Ghali 2019; Maehle et al. 2015). An additional theoretical contribution of this study consists of the adaptation and the test, in marketing field, of the SES measurement scale, which was widely used in medical field.

As for the practical implications of the study, the authors aimed to examine the association between the socioeconomic profile of the consumer and organic food consumption in Tunisia. Such data are significant for creating marketing strategies and programs that are mandatory to develop the organic food market. Indeed, the findings showed a positive and significant relationship between SES and organic food consumption. This seems useful for practitioners for a better understanding of consumer behavior toward organic food. In fact, in order to better communicate the perceived values (hedonic vs utilitarian) of organic food, managers should segment their markets based on the consumers’ SES. High SES level consumers are more willing to buy and pay the premium price of organic food when they are aware of its perceived values. Therefore, for this segment of consumers, practitioners should deliver rich information about the benefits of organic consumption for health and the environment and make the consumer aware that higher prices correspond to better quality, reliability, safety and purity in organic food. Moreover, marketers could leverage the hedonic benefits of the consumption of organic food by engaging in emotional appeal advertising. This will allow the linking of the product with indulgence to stimulate pleasure and enjoyment (Maehle et al. 2015). Yet the consumer’s desire for pleasure and enjoyment can be met through multi-sensory marketing with the highlighting of the hedonic properties of the product (attractive package, visual aspect of freshness and good taste, etc.). Low SES consumers, on the other hand, are less interested in these foods. Therefore, practitioners should bring these products closer to them and improve their availability especially in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Furthermore, through their communication strategies, marketers should focus on the positive social and environmental reputation to gain market share from less environment-friendly competitors. In addition, producers of organic food should use short distribution chains in order to control costs and remain closer to the consumer.

In spite of its multiple contributions, the present study is not devoid of some limitations, which could open new paths for further research. First, the operationalization of SES was performed through only three indicators, namely income, education and occupation. These indicators might change with time in every community due to the very dynamics of human existence. Therefore, other authors considered additional indicators to measure this concept like neighborhood, social status, social class and memberships to any social groups (El-Gilany et al. 2012; Kranjac et al. 2017). Further research woks can focus on the elaboration of a measurement scale of this interesting concept in marketing field for better understanding of consumer behavior. Second, for the variables organic food perceived values, WTP and WTB, we used scales that have already been created and measured in developed markets. Further studies should develop reliable measurement scales for emerging markets in order to investigate the different parameters related to these markets. Third, the test of the conceptual model in developed markets where SES is more important and where consumers are more familiarized with organic food consumption would be useful in order to generalize it.

Conclusion

The socioeconomic status have shown significant positive association with the consumer behavior toward organic food. More than the consumers have high level of SES, more they are concerned by the values of organic foods and, consequently, willing to buy and to pay for them. These findings might have interesting contributions for the practitioners in field of organic food to segment their markets based on the level of consumer’s SES and adapt, hence, their marketing strategies based on the characteristics of every segment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aggarwal OP, Bhasin SK, Sharma AK, Chhabra P, Aggarwal KP. A new instrument (scale) for measuring the socioeconomic status of a family: Preliminary study. Indian J Community Med. 2005;30(4):211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Alkerwi A, Vernier C, Sauvageot N, Crichton GE, Elias MF. Demographic and socioeconomic disparity in nutrition: application of a novel Correlated Component Regression approach. BMJ Open. 2015;5:1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alphonce R, Alfnes F. Eliciting consumer WTP for food characteristics in a developing context: application of four valuation methods in an African market. J Agric Econ. 2017;68(1):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Altarawneh M. Consumer awareness towards organic food: a pilot study in Jordan. J Agric Food Technol. 2013;3(12):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- American Department of Agriculture (2015) National organic program. https://www.ams.usda.gov/about-ams/programs-offices/national-organic-program. Accessed 3 June 2020

- Anastasiou CN, Keramitsoglou KM, Kalogeras N, Tsagkaraki MI, Kalatzi L, Tsagarakis KP. Can the “Euro-leaf” logo affect consumers’ willingness-to-buy and willingness-to- pay for organic food and attract consumers’ preferences? An empirical study in Greece. Sustainability. 2017;9(8):1450. [Google Scholar]

- Ann WR, Walsh W. The intersectionality of socioeconomic status (SES) and social class on the therapeutic alliance with older adult clients. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work. 2020;90(1–2):96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Arvola AM, Vassallo M, Dean P, Lampila A, Saba L, Lahteenmaki L, Shepherd R. Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: the role of affective and moral attitudes in the theory of planned behavior. Appetite. 2008;50(2):443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal K, Chaudhary P, Pandit S, Sharma G. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic products: a case from kathmandu valley. J Agric Environ. 2009;10:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Babin BJ, Darden WR, Griffin M. Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J Consum Res. 1994;20(4):644–656. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structure equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988;16(1):74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Batat W, Peter PC, Vicdan H, Manna V, Ulusoy E, Uiusoy E, Hong S. Alternative food consumption (AFC): idiocentric and allocentric factors of influence among low socio-economic status (SES) consumers. J Mark Manag. 2017;33(7–8):580–601. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann S, Szabo M, Johnston J. Understanding the food preferences of people of low socioeconomic status. J Consum Cult. 2017;19(3):316–339. [Google Scholar]

- Costa BVL, Menezes MC, Oliveira CDL, Mingoti SA, Jaime PC, Caiaffa WT, Lopes ACS. Does access to healthy food vary according to socioeconomic status and to food store type? An ecologic study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:775. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6975-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl CL, Beresford SAA, Hajat A, Kaufman JD, Moore K, et al. Associations of organic produce consumption with socioeconomic status and the local food environment: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditlevsen K, Sandoe P, Lassen J. Healthy food is nutritious, but organic food is healthy because it is pure: the negotiation of healthy food choices by Danish consumers of organic food. Food Qual Prefer. 2019;71:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds WD, Monroe K, Grewal D. Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J Mark Res. 1991;28(3):307–319. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gilany A, El-Wehady A, El-Wasify M. Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(9):962–968. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.9.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fuljahn A, Moosmayer DC. The myth of guilt: a replication study on the suitability of hedonic and utilitarian products for cause related marketing campaigns in Germany. Int J Bus Res. 2011;11(1):85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ghali Z. Motives of willingness to buy organic food under the moderating role of consumer awareness. J Sci Res Rep. 2019;25(6):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ghali ZZ, Toukabri M. The antecedents of the consumer purchase intention: sensitivity to price and involvement in organic product: moderating role of product regional identity. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;90:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Ghosh T. Modification of Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale in context to Nepal. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:1104–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginon E, Combris P, Loheac Y, Enderli G, Issanchou S. What do we learn from comparing hedonic scores and willingness-to-pay data? Food Qual Prefer. 2014;33:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- González MG, Swanson DP, Lynch M, Williams GC. Testing satisfaction of basic psychological needs as a mediator of the relationship between socioeconomic status and physical and mental health. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(6):972–982. doi: 10.1177/1359105314543962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govidnasamy R, Italia J. Predicting willingness-to-pay a premium for organically grown fresh produce. J Food Distrib Res. 1990;46:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Groth MV, Fagt S, Brondsted L. Social determinants of dietary habits in Denmark. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:959–966. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranjac M, Vapa-Tankosic J, Knezevic M. Profile of organic food consumers. Econ Agric. 2017;64(2):497–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lantos GP. Consumer behavior in action: real-life applications for marketing managers. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Yun ZS. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;39:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lim WM, Yong JL, Suryadi K. Consumers’ perceived value and willingness to purchase organic food. J Global Mark. 2014;27:298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lio CH, Hsieh IY. Determinants of consumer's willingness to purchase gray-market smartphones. J Bus Ethics. 2013;114(3):409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Chen CW, Chen HS. Measuring consumer preferences and willingness to pay for coffee certification labels in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2019;11:1297. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro ML, Mccluskey JJ, Mittelhammer RC. Assessing consumer preferences for organic, eco-labeled, and regular apples. J Agric Resour Econ. 2001;26(2):404–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Chi CG. An examination of the perceived value of organic dining. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2018;30(8):2826–2844. [Google Scholar]

- Maehle N, Iversen N, Hem L, Otnes CC. Exploring consumer preferences for hedonic and utilitarian food attributes. Br Food J. 2015;117(12):3039–3063. [Google Scholar]

- Molarius A, Berglund K, Eriksson C, Lambe M, Nordström E, Eriksson HG, Feldman I. Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:125–133. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassivera F, Troiano S, Marangon F, Sillani S, Markova NI. Willingness to pay for organic cotton: consumer responsiveness to a corporate social responsibility initiative. Br Food J. 2017;119(8):1815–1825. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer RG, Krishnan B, Pullig C, Wang G, Yagci M, Dean D, Ricks J, Wirth F. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J Bus Res. 2004;57(2):209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Padel S, Foster C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behavior: understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br Food J. 2005;107(8):606–625. [Google Scholar]

- Pechey R, Monsivais P. Socioeconomic inequalities in the healthiness of food choices: Exploring the contributions of food expenditures. Prev Med. 2016;88:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petljak K, Stulec I, Renko S. Consumers’ willingness to pay more for organic food in Croatia. Ekonomski Vjesnik. 2017;30(2):441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu K, Han H, Jang SS. Relationships among hedonic and utilitarian values, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in the fast-casual restaurant industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2010;22(3):416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar D, Shai I, Vardi H, Shahar A, Fraser D. Diet and eating habits in high and low socioeconomic groups. Nutrition. 2005;21(5):559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev E, Morwitz VG. Influence via comparison-driven self-evaluation and restoration: the case of the low-status influencer. J Consum Res. 2012;38(5):964–980. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Verma P. Factors influencing Indian consumers' actual buying behavior towards organic food products. J Clean Prod. 2017;167:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney JC, Soutar GN, Johnson LW. The role of perceived risk in the quality-value relationship: a study in a retail environment. J Retail. 1999;75(1):77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Teng CC, Lu CH. Organic food consumption in taiwan: motives, involvement, and purchase intention under the moderating role of uncertainty. Appetite. 2016;105:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang J, Huo X. Consumer’s willingness to pay a premium for organic fruits in China: a double-hurdle analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(126):3–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CJ, Tong E. On linking socioeconomic status to consumer loyalty behaviour. J Retail Consum Serv. 2019;50:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Kim HC. Feeling economically stuck: the effect of perceived economic mobility and socioeconomic status on variety seeking. J Consum Res. 2017;44(5):1141–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda L, Li J. Characteristics of organic food shoppers. J Agric Appl Econ. 2007;39(01):17–28. [Google Scholar]