Abstract

The purpose of this study was to provide contextual information on indigenous food’s technologies and safety from Gabon. The strategic focus being to promote local food with enhanced nutritional value and improved safety. An investigation and monitoring were carried out to elucidate their process flow diagrams and to identify safety failures. Samples were taken for microbiological analysis using conventional culture-based techniques. Detection and identification of Salmonella in samples were confirmed using PCR based method by targeting invasion plasmid antigen B (IpaB) gene. The investigation shows that women play a protagonist role in the technical know-how of Gabonese indigenous foods in a context that is evolving towards the disappearance of this knowledge. The food production process remains archaic, which makes the environment impact on food safety. Indeed, the proximity of food manufacturing environment to animals, waste, or latrines coupled with the lack of hygiene and manufacturing practices affect the quality of these foods. This is reflected in our study's microbiological results, namely, Aerobic Mesophilic Bacteria ranged from 3.53 to 11.96 log CFU/g and indicators of fecal contaminations of up to 8.21 log CFU/g. Salmonella is detected in 18.69% of samples. The presence of these bacteria is a risk for consumer health. Although some of these foods can be considered as a fermented food, the producers should be further educated and encouraged to take preventive measures to ensure the quality of these food products. A much more subtle approach based on microbial ecology of these foods should be explored for better exploitation.

Keywords: Indigenous foods, Safety, Food technology, Salmonella, Gabon, PCR

Introduction

Indigenous foods hold a firm place in the cooking from almost every culture in the world. The diet of African people includes a wide range of indigenous foods (Odunfa and Oyewole 1998). However, in the current context created by globalization, the African continent is facing a crisis of food cultural identity. Indeed, city dwellers’ lifestyle and consumption, especially the emergence of the middle social class show a tendency towards food diversification and a growing marginalization of local products. In these circumstances, indigenous foods are subject to competition from imported food in a context that is unfavorable for them due to the slow evolution of processing technologies that urban cookers find tedious (Nout et al. 2003). Recent studies from Africa have shown the presence of Salmonella spp. (Bsadjo–Tchamba et al. 2015) or pathogenic Listeria monocytogenes (Owusu-Kwarteng et al. 2018) in processed foods at risk of environmental contamination. The observation of high enteropathogens prevalence in the environment due to the lack or low level of sanitation in African city, as noted in the study by Traoré et al. (2015), highlights the permanent danger for consumers in event of noncompliance with strict hygiene and food safety practices during food processing.

In Gabon, a tropical country with amazing variety of wildlife and plants, foods exposed in the environment would be ideal biotopes still under-explored of pathogenic or wild bacteria with high potential. Few studies to date have focused on the environmental impact on the microbiological quality of indigenous foods in Gabon, and, yet, they are highly exposed during their production. However, some studies have shown the importance of food widely consumed by the Gabonese people and their mode of transformation (Ondo-Azi et al. 2013, 2014; Muandze-Nzambe et al. 2017). The aim of this study is to aid in the development of African indigenous food products with enhanced nutritional value and improved safety characteristics from locally derived raw materials. In this paper, we present some indigenous foods' manufacturing processes of Gabon with the unitary steps of microorganism contamination or proliferation and the associated microorganisms of these indigenous foods.

Materials and methods

Study site, period and investigation

This study was conducted from February to December 2018 in Gabon and concerned 3 Gabonese cities, namely Libreville, Franceville, and Lambaréné. Face-to-face interviews of 56 various ethnic social group’s people were conducted about their manufacturing know-how on indigenous food of Gabon. All data were collected following an adapted set of questions and monitoring. The study questionnaire was organized into distinctive sections to obtain information about manufacturing skill level for highlight qualified producers, their socio-demographic characteristics, level of knowledge and training on food hygiene, and also to list known foods and their target of production. A randomized number of 8 available producers from Libreville, Franceville, and Lambaréné were selected among qualified producers as regards production monitoring. The selected ethnic groups were Fang, Guissira, Kota, Miènè, Nzebi, Obamba-Téké and Punu. The same questionnaire was administered to each producer. This sheet allowed us to elucidate the process flow diagram for each traditionally produced food from the treatment of the raw material to the finished product. Besides, to evaluate the traditional production process about compliance with hygiene and food safety practices during the manufacturing process. Specifically, the observation of hygienic characteristics such as the use of protective and suitable working clothes, hand washing with clean water, the use of washing and sanitizing products, the separation of clean and dirty work areas, having a good distance between the toilets and the workspace and finally the absence of waste, animals, stagnant water, and insects near the food production area. Then, an annotation scale on hygienic characteristics for each producer has been assigned as follows, 0: Bad, 2.5: Unsatisfactory, 5: Satisfactory, 7.5: Acceptable and 10: Excellent.

Sampling for microbiological analysis

For indigenous food that are not sold in markets such as Ayagha m’ombolo, Soukoutê, Litoki, Liwaye and cassava dough used to manufacturing Baton de manioc, formulation prepared by the monitored producers was collected before and/or after cooking for microbiological analysis. The indigenous food sold in markets such as Baton d’atanga, Mfourn, Poisson salé, Poisson fumé and Atchrougou have been sampled in the selling point of monitored producers. A total of 123 samples of Gabon’s indigenous foods were done randomly. The samples were taken aseptically in triplicate. Each bag containing the samples were labeled with all product information. Then, samples were transported to the laboratory under refrigeration conditions for further analysis. The samples number for each indigenous food was greater than or equal to 3 (n ≥ 3).

Microbiological analyses of samples

For all the analyses, 10 g of sample was dissolved in 90 mL of sterile peptone-salt. Then, serial dilutions were monitored with this suspension. All tests were done in duplicate. The results were expressed as colony-forming unit per gram (CFU/g). The aerobic mesophilic bacteria (AMB) were cultured on the PCA medium (Plate Count Agar; Difco). All colonies on the Petri dish [30–300] were counted 72 h post-incubation at 30 °C. For fecal pollution, thermotolerant coliforms enumeration was carried out on EMB agar (Eosin Methylene Blue; bioMérieux) after incubation at 44 °C during 24 h. Petri dishes with 15–300 dark purple colonies were examined. Bacillus were cultured on the PCA medium (Plate Count Agar; Difco) for each serial dilutions heated beforehand at 85 °C during 20 min in a bath. After 24 h of incubation at 30 °C, Petri dishes containing 30 to 300 colonies were examined and the colonies were counted. Enterococci were cultured on the BEA medium (Bile Esculin Agar; Difco). After 24 h of incubation at 35 °C, all distinctive colonies with black haloes were enumerated. Yeasts and molds were isolated on SAB-CHL agar (Sabouraud chloramphenicol; bioMérieux). All colonies on the Petri dishes [10–150] were counted 48–72 h post-incubation at 25–30 °C.

Detection of Salmonella in samples

The Gabonese indigenous foods samples were analysed for the presence of Salmonella based on standard methods described in the Laboratory Microbiology Guidebook of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service and Bacteriological Analytical Manual of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Thus, 25 g of food sample was added to 225 mL of BPW (Buffered Peptone Water; BioMérieux), mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h. An aliquot of 0.1 mL was transferred to 10 mL of RV broth (Rappaport Vassiliadis, BioMérieux) and incubated for 24–48 h at 42 °C. An aliquot portion (10 μL) was then streaked on SS agar (Salmonella-Shigella; BioMérieux) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colonies exhibiting typical Salmonella morphology on SS Agar plates were preliminarily selected using biochemical tests. After the discrimination between Salmonella, Proteus and Citrobacter, the final confirmation of presumptive Salmonella was made by using API-20E and PCR analysis.

PCR assay of presumptive Salmonella isolates

Briefly, suspect colonies were grown on MH agar (Mueller Hinton; BioMérieux) at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, several pure culture colonies were suspended in 300 μL of sterile distilled water (Nuclease Free Water, QIAGEN). Isolates of DNA were extracted using the QIAamp®DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The presence of nucleic acid was confirmed by quantification and purity analysis performed using a Nanovue™ Plus Spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare Bio-Science Corp, Cambridge, UK). Supernatant DNA lysate was transferred into sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf® tubes for storage at − 5 °C pending amplification. Amplification of IpaB gene was carried out using the method described by Kong et al. (2002). The reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 μM of each of the specific PCR primers, 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 0.2 μM of each dNTP and 1 X PCR Mix buffer (20 μM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.4, 50 μM KCl and 2.5 μM MgCl2). PCR amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) under the following conditions: heat denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of heat denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, primer annealing at 62 °C for 1 min and DNA extension at 72 °C for 2.5 min. This was followed by incubation at 72 °C for 10 min and cooling at 4 °C. Positive control reaction contained DNA of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC®14,028™). Negative control reaction mixtures contained sterile distilled water (Nuclease Free Water, QIAGEN) in place of template DNA mg/ml ethidium bromide in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 89 mM boric acid, 2.5 mM EDTA). DNA bands were visualized by UV illumination and photographed using the Gel Doc 1000 documentation system (Bio-Rad, France).

Data processing and statistical analysis

The frequencies of different variables evaluated during the survey were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2013 software. The chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variables among the groups. The nonparametric Fisher’s exact test were used for group comparison. The plate count data were converted to log CFU/g. The statistical analysis was performed using the R software version 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria) for processed data from microorganism enumeration. Results were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means, standard deviation and the least significant difference between the means were determined. For all analyzes, the threshold of significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Indigenous foods production of Gabon: context, hygiene, processing, and environment

Survey information

The pre-investigation confirms that cooking indigenous Gabonese food is a women's activity. Indeed, people approached at first, without distinction as to sex, sent us automatically to women manual workers. Respondents with a working knowledge of indigenous food processes represent qualified producers of the study. The results suggest a disparity in the distribution of qualified producers according to their ages (p < 0.01). The same around the distribution of respondents with working knowledge on indigenous food processes by age group and the level of education (p = 0.09). Thus, 41.07% of qualified producers on indigenous foods production, only 26.08% reported working in the food sector: namely 8.69% in home sales and 15.37% in retail markets. The other respondents with working knowledge of indigenous food processes (73.91%) make their food products for family consumption. The findings of the investigation show that the producer’s expertise in knowledge of traditional foods production is transmitted from mother to daughter. The survey reveals that the manufacturing processes for indigenous foods are specific from one producer to another, from one ethnic group to another and from one region to another. Table 1 summarizes data of investigation.

Table 1.

Socio-cultural characteristics overview of the producers surveyed about traditional foods

| Qualified producers | Number (%) | p-value | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||

| [18–50[ | [50–90] | |||

| Yes | 05 (08,93%) | 18 (32,14%) | – | 23 (41.07%) |

| No | 29 (51,79%) | 04 (07,14%) | – | 33 (58,93%) |

| Total (%) | 34 (60,72%) | 22 (39,28%) | 7.56 e−7 | 56 (100%) |

| Qualified producers’ education level | [18–50[ | [50–90] | p-value | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| illiterate | 00 | 08 (34.78%) | – | 08 (34.78%) |

| Primary | 02 (08.69%) | 01 (04.35%) | – | 03 (13.04%) |

| Secondary | 01 (04.35%) | 04 (17.39%) | – | 05 (21.74%) |

| Superior | 02 (08.69%) | 05 (21.74%) | – | 07 (30.43%) |

| Total (%) | 05 (21.74%) | 18 (78.26%) | 0.09 | 23(100%) |

| Target of indigenous foods production | Number (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| For sale | ||

| In home | 02 (8.69%) | 06 (26.08%) |

| In retail market | 04 (15.37%) | |

| family consumption | 17 (73.91%) | 17 (73.91%) |

| Total (%) | – | 23 (100%) |

| Qualified producers’ ethnic group of the study | Number of qualified producers | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nzébi | 03 (13.04%) | 23 (100%) |

| Téké-Obamba | 07 (30.43%) | |

| Kota | 02 (8.69%) | |

| Miènè | 03 (13.04%) | |

| Guissira | 03 (13.04%) | |

| Fang | 04 (17.39%) | |

| Punu | 01 (4.35%) |

| Listed indigenous food | Qualified producers’ ethnic group | Number of qualified producers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ayaga m’ombolo | Téké–Obamba | 04 (17.39%) |

| Soukoutê | Téké–Obamba; Kota | 05 (21.74%) |

| Baton d’atanga, Oyaba or Ofêdê | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Miènè; Guissira; Kota | 12 (52.17%) |

| Nkono mbo or Paquet de manioc | Fang; Kota | 02 (8.69%) |

| Baton de manioc | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Miènè; Guissira; Fang; Kota; Punu | 23 (100%) |

| Mbounda Bokoulou, Lewaye | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Kota | 05 (21.74%) |

| Atchrougou or Oyirri | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Kota | 09 (39.13%) |

| Ndok, Mudika or Chocolat | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Miènè; Guissira | 08 (34.78%) |

| Bogou or Ompéri | Miènè; Guissira | 05 (21.74%) |

| Litoki | Nzébi | 02 (8.69%) |

| Pate d’arachide or Mfourn | Nzébi; Téké–Obamba; Miènè; Guissira; Fang; Kota; Punu | 20 (86.96%) |

| Poisson fumé | Miènè; Guissira; Fang; Punu | 08 (34.78%) |

| Poisson salé | Téké–Obamba; Miènè; Guissira | 05 (21.74%) |

| Qualified producers | Number (%) of producers with working knowledge | Manufacturing skill | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous food | Number of qualified producers (%) | ||

| Libreville | 15 (65.22%) | Ayaga m’ombolo | 02 (8.69%) |

| Soukoutê | 01 (4.35%) | ||

| Baton d’atanga | 05 (21.74%) | ||

| Nkono mbo or Paquet de manioc | 02 (8.69%) | ||

| Baton de manioc | 15 (65.22%) | ||

| Mbounda Bokoulou, Lewaye | 05 (21.74%) | ||

| Atchrougou or Oyirri | 06 (26.09%) | ||

| Ndok, Mudika or Chocolat | 02 (8.69%) | ||

| Bogou or Ompéri | 02 (8.69%) | ||

| Litoki | 02 (8.69%) | ||

| Pate d’arachide or Mfourn | 12 (52.17%) | ||

| Poisson fumé | 03 (13.04%) | ||

| Lambaréné | 04 (17.39%) | Baton d’atanga | 03 (13.04%) |

| Baton de manioc | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Ndok, Mudika or Chocolat | 03 (13.04%) | ||

| Bogou or Ompéri | 03 (13.04%) | ||

| Pate d’arachide | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Poisson fumé | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Poisson salé | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Franceville | 04 (17.39%) | Ayaga m’ombolo | 02 (8.69%) |

| Soukoutê | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Baton d’atanga, Oyaba or Ofêdê | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Baton de manioc | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Atchrougou or Oyirri | 03 (13.04%) | ||

| Ndok, Mudika or Chocolat | 03 (13.04%) | ||

| Pate d’arachide | 04 (17.39%) | ||

| Poisson fumé | 01 (4.35%) | ||

| Poisson salé | 01 (4.35%) | ||

| Total (%) | 23(100%) | – | – |

Environmental, hygiene and safety aspects

The investigation reveals that producers’ knowledge level about food safety is very low. The manufacturing of Gabon’s indigenous foods is dominated by a sequence of manual operations that regularly take place in inappropriate environments. The traditional processes of food preparation would expose them to hazards. The 100% of producers monitored confirm the unsatisfactory level of hygiene during the Gabonese indigenous foods production. Among them, only one producer who lives in Libreville respects hygiene practices and would have benefitted training in food hygiene commensurate with his work activity. Although all indigenous food producers use protective and suitable working clothes, unfortunately, these are often not worn in accordance with the Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). They often use inappropriate water and only soap to wash and disinfect production equipment. As well, it appears that the production areas of indigenous food are not properly installed or maintained in the strategic and sustainable way to limit potential environmental factors that may affect the quality of food. Animals, insects and stagnant water are present near all production areas of indigenous food. The lowest score during the monitoring has been obtained by producers of Poisson salé and Poisson fumé. Besides, the storage and sales conditions of these foods in the retail market remain rudimentary: without packaging devices, exposing consumers’ health. Table 2 summarizes the data collected during the women workers’ monitoring in order to inform on compliance of hygiene practices.

Table 2.

Data collected during the women workers’ monitoring

| Hygienic characteristics | Criteria | NC* | Mean of annotation scale each monitored producers on hygienic characteristics | LS* | HS* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The use of protective and suitable working clothes | Bad | 0 | 6.25 | 2.5 | 7.5 |

| Unsatisfactory | 2 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 6 | ||||

| Excellent | 0 | ||||

| Hand washing with clean water | Bad | 5 | 3.75 | 00 | 10 |

| Unsatisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 0 | ||||

| Excellent | 3 | ||||

| The use of washing and sanitizing products | Bad | 0 | 5.625 | 05 | 10 |

| Unsatisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 7 | ||||

| Acceptable | 0 | ||||

| Excellent | 1 | ||||

| The separation of clean and dirty work areas | Bad | 2 | 2.50 | 00 | 7.5 |

| Unsatisfactory | 5 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 1 | ||||

| Excellent | 0 | ||||

| Having a good distance between the toilets and the workspace | Bad | 3 | 6.25 | 00 | 10 |

| Unsatisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 0 | ||||

| Excellent | 5 | ||||

| The absence of waste near the food production area | Bad | 1 | 5.625 | 2.5 | 10 |

| Unsatisfactory | 2 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 4 | ||||

| Excellent | 1 | ||||

| The absence of animals near the food production area | Bad | 2 | 2.18 | 00 | 05 |

| Unsatisfactory | 5 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 1 | ||||

| Acceptable | 0 | ||||

| Excellent | 0 | ||||

| The absence of insects near the food production area | Bad | 2 | 1.875 | 00 | 2.5 |

| Unsatisfactory | 6 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 0 | ||||

| Acceptable | 0 | ||||

| Excellent | 0 | ||||

| The absence of stagnant water near the food production area | Bad | 1 | 3.44 | 00 | 7.5 |

| Unsatisfactory | 4 | ||||

| Satisfactory | 2 | ||||

| Acceptable | 1 | ||||

| Excellent | 0 | ||||

| Means | – | – | 4.17 | 1.11 | 7.78 |

Nc number of criteria, LS monitored producers with lowest score, HS monitored producers with highest score

Description and technological aspects

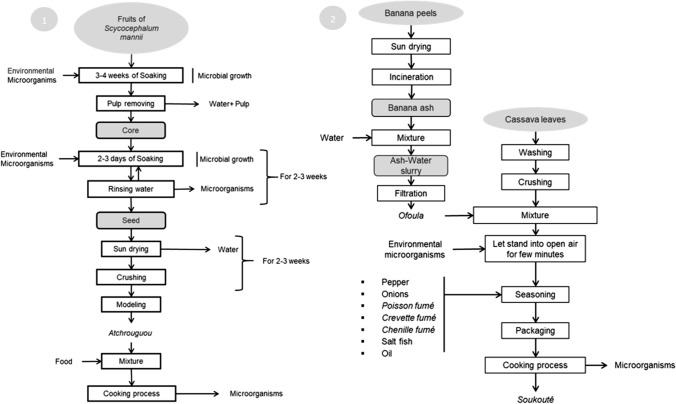

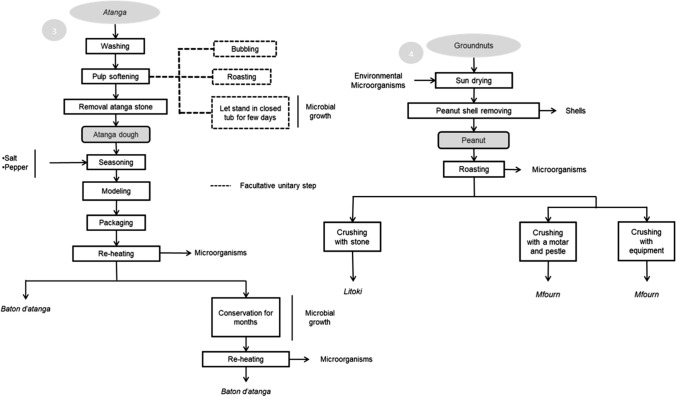

The producers monitored during the manufacturing allowed us to elucidate the pattern of a technological method for the manufacture of each observed indigenous food. The objective was to highlight or predict the hazardous practices to ensure optimum safety of the high-risk unitary process during indigenous food manufacturing. A total of 13 indigenous foods, either condiments or dishes, were described in this study. Process flow diagrams are described in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, specifically:

Fig. 1.

Monitored process flow diagrams, Legend.1: Atchrougou process; 2: Ofoula and Soukoutê process

Fig. 2.

Monitored process flow diagrams (continued), Legend. 3: Baton d’atanga process; 4: Mfourn and Litoki process

Fig. 3.

Monitored process flow diagrams (continued), Legend. 5: Baton de manioc process; 6: Ayaga m’ombolo process; 7: Lewaye process

Fig. 4.

Monitored process flow diagrams (continued), Legend. 8: Poisson salé and Poisson fumé process; 9: Bogou and Mudika process

Atchrougou: also know as Oyiri is a condiment obtained from fruits seeds of Scyphocephalum manii used to improve the flavor of many dishes. Soukoutê: a special cooked dish from cassava leaves intended for cooked consumption. Ofoula: indigenous additive obtained using ash from burned banana peels suspended in water (ash-water slurry). The Ofoule is used for Soukoutê preparation and various other dishes (Fig. 1).

Baton datanga: also known as Oyaba; Ikwête; Ofêdê or Moubombo is an obtained dough after processing of Dacryodes edulis fruits that may be consumed hot or cold. Litoki and Mfourn: peanut butter used for the cooking of many dishes and often used as a spread (Fig. 2).

Cassava dough: raw dough obtained after the processing of cassava root and consumed after cooking in form of Baton de manioc. Ayaga mombolo: a fermented dish from cassava leaves intended for cooked consumption. Lewaye: also known as Mbounda bokoulou is a condiment from seeds of Hibiscus sabdariffa used to improve the flavor of many dishes (Fig. 3).

Poisson salé and Poisson fumé: condiment obtained from fresh fishes for the preparation of many dishes but also can be appreciated when eaten raw by a tasty way served with Baton de manioc among some Gabonese. Bogou: a food obtained by processing seeds of Irwinga gabonensis and used for the cooking of a special indigenous sauces. The Bogou can be eaten raw too. Mudika: a food like Bogou obtained by processing seeds of Irwinga gabonensis. Also known as Ndok or Chocolat, Mudika is used for the cooking of a special indigenous sauce (Fig. 4).

Women workers are mainly involved in the beginning, heart, and end of the indigenous food chain; i.e. from the raw materials’ supply until the service. This work confirms the studies of the food sector in Africa which show that indigenous food preparation is an essentially female activity (FAO, 2007). The gradual knowledge disappearance of Gabonese indigenous foods is illustrated by the survey findings, namely: a larger number of age group women [50–90] with working knowledge on indigenous food processes and also these qualified women distribution in comparison with their level of education. However, the presence of some indigenous food in retail markets involves their potentials income source for women. Unfortunately, the monitoring indicated that hygiene practices are low during the production of indigenous food. This would be explained by the application of very meticulous operations according to tedious and ancestral traditional techniques. These manufacturing steps would represent a limit for quality, safety, and standardization of the finished product according to some authors (Sanni et al., 2002; Capozzi et al., 2017; Muandze-Nzambe et al., 2017), even if several of those unfavorable manufacturing conditions give them their recognizable characteristics (Odunfa & Oyewole, 1998; Ebuehi & Oyewole, 2008). Moreover, indigenous foods such as Poisson salé, Poisson fumé or Atchrougou often sold in retail markets near waste constitutes significant risks. However, other Gabonese foods such as Baton de manioc, Baton d’atanga, Nkono mbo or Bogou are carried out in a specific packaging based on plant leaves. Indeed, in tropics, certain plant leaves such as the leaves of Malvaceae family, Marantacaeae family and Musa sinensis are used by indigenous populations for food packaging. Generally, these leaves are selected for their flexibility and strong water-proofing quality. Studies have shown that none of the leaves would contain any toxins, dyes or irritants. Moreover, these leaves would have properties concerning the protection and for the organoleptic and therapeutic qualities of the food. Besides, these packaging practices perpetuate the traditions of these foods that differentiate them from others (Adejumo and Ola 2008).

Indigenous foods would be exposed to microorganisms during processing. Assessed hygienic characteristics have shown noncompliance with GMP according to FAO (2007). Most of women workers monitored in this study had obtained annotation scales under 5. Many production practices regarded as critical points were found; namely manual operations, poorly washed and disinfected materials and improper storage conditions that could promote contamination or multiplication of microorganisms. However, these critical points regarding microbiological hazards could be corrected during one efficient heat treatment like the cooking process. Only one woman workers received training that had a real effect on their manufacturing practices of indigenous foods. The FAO recommendations on GMP of this woman worker were in compliance (FAO, 2007). However, hygienic characteristics regarding the presence of animals and insects have remained bad. Indeed, animals like rats, geckos or flies are often have been found near producing areas notwithstanding safe provisions. As a sustainable solution for this purpose, the use of repellent plants with promising essential oil namely, Cymbopogon spp., Ocimum spp., Thymus spp., and Eucalyptus spp. could be considered and evaluated (Singla et al., 2014). The manufacturing steps like the process of let food into open-air represent a critical point. This operation is often used in the production of Ayaga m’ombolo, Soukoutê, Baton de manioc, Atchrougou, Bogou, peanut butter (Litoki and Mfourn), Poisson salé, and Poisson fumé. Although these unit steps are intended for dry using sun, foods are also exposed to risks associated with environmental microorganisms. Other processes such as the brining used for Poisson salé production may reduce the microbiological hazard when the products are kept in the brine for a sufficient time but may not eliminate it. By contrast, the unitary step of fish’s transversally opening in two for Poisson salé production involving a gutting would reduce the hazards but may not eliminate it, especially if the environment and the bacteriological quality of the water in which fish are harvested is poor (Sanni et al. 2002). The intestinal bacteria of the ungutted fish represent a poorly controlled starter for bacteria multiplication in case of conservation or storage steps during fish production. Studies indicate the importance of basic treatments such as gutted and extensively washing using clean water before fish drying to reduce microorganisms’ contaminations (Sanni et al. 2002; Tanasupawat and Visessanguan 2014). For indigenous foods products such as Poisson salé, Atchougou or Baton de manioc, the step of soaking for a few days tends to stimulate microorganism proliferation. This soaking appears to be a key factor in loosening the structure of food during processing. This step affects finish product consistency, smell, appearance, and color (Ebuehi and Oyewole 2008). Given the importance of some of these steps involving microorganisms for the genesis of organoleptic characters, a new approach based on microbial biotechnology would allow the use of starter culture to maintain organoleptic characteristics and ensure their safety (Capozzi et al. 2017).

In the context of artisanal food production, water represents an important source of food contamination. Indeed, the precarious sanitation system in developing countries is forcing people to defecate in the wild. Also, monitoring indicates in some cases existing proximity between production sites, latrines, and sites of domestic waste disposal. In this way, Natural freshwater resources from Gabon are contaminated through the runoff and erosion phenomena in this area characterized by high rainfall and mountainous terrains. This makes that rivers and lakes represent potential hazard sources of the enteric pathogens. Ehrhardt et al. (2017) have found a strong load of Salmonella and bacteria that indicates fecal contamination in water resources of Gabon. These findings suggest the risk to the health of untreated natural water use from these areas. Besides, Gabon is a forest country with rich wildlife. This suggests natural promiscuity between humans and wildlife in this region. Animals that defecate in the wild contaminate also natural waters. The use of these waters would represent a transfer way for bacteria toward humans through food. The monitoring has shown the presence of animals and insects near the food producing's areas: this can also be taken as sources of potential biological dangers. Indeed, studies have clearly shown animals as sources of pathogenic bacteria (Sanchez et al. 2002). Animals such as rodents, lizards, and pets can play significant roles in pathogens' transmission through food (Raufu et al. 2019). Also, studies have highlighted that flies can transmit bacteria in food through regurgitation, translocation from the exoskeleton and defecation (Pava-Ripoll et al. 2012). The ecology of Poisson salé production has shown a special mark: the presence of Cattle Egret scientifically called Bubulcus ibis. These birds are widely found in Poisson salé production and could represent vectors of undesirable microorganisms.

Microbiological data acquired from studied Gabonese indigenous foods

All microbiological analysis results of sampled indigenous foods from Gabon are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Microbial load of sampled indigenous foods

| Samples | Logarithm of Colony Forming Units/gram (log CFU*/g) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB* | Bacillus | Enterococcus | Yeast and Molds | Thermotolerant Coliforms | ||||||||||||||||

| basic statistical parameters | M* | SD* | Min* | Max* | M* | SD* | Min* | Max* | M* | SD* | Min* | Max* | M* | SD* | Min* | Max* | M* | SD* | Min* | Max* |

| Traditional dishes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| a* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ayaga m’ombolo before cooking | 11.96 | 11.29 | 11.77 | 12.04 | 11.24 | 11.09 | 10.69 | 11.61 | 9.39 | 8.80 | 9.18 | 9.49 | 7.48 | 6.66 | 7.37 | 7.59 | 5.76 | 4.65 | 5.71 | 5.80 |

| Cassava dough before cooking | 6.98 | 6.90 | 5.85 | 7.46 | 5.40 | 4.70 | 5.24 | 5.49 | und* | und* | und* | und* | 6.18 | 6.06 | 4.23 | 6.62 | < 3 | / | / | / |

| b* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ayaga m’ombolo after cooking | > 6.48 | / | / | / | > 6.48 | / | / | / | 5.72 | 5.03 | 5.22 | 5.84 | 4.54 | 3.8 | 4.31 | 4.79 | < 3 | / | / | / |

| Soukoutê | > 6.48 | / | / | / | 5.08 | 4.86 | 4.35 | > 6.48 | 3.65 | 3.06 | < 3 | 3.75 | 3.84 | 3.86 | < 3 | 2.87 | < 3 | / | / | / |

| Condiments | ||||||||||||||||||||

| c* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Baton d’atanga before heating | 6.76 | 5.94 | 6.67 | 6.85 | 5.12 | 4.30 | 5.01 | 5.18 | 3,16 | 2.60 | 3.03 | 3.31 | 3.40 | 2.54 | 3.30 | 3.48 | < 3 | / | / | / |

| Baton d’atanga after heating | 4.36 | 4.13 | 4.00 | 4.72 | 4.26 | 3.35 | 4.19 | 4.33 | < 3 | / | / | / | < 3 | / | / | / | < 3 | / | / | / |

| Bogou | > 6.48 | / | / | / | > 6.48 | / | / | / | 3.45 | 2.95 | 3.02 | 3.57 | 6.84 | 6.43 | 6.39 | 6.95 | 4.04 | 3.85 | 3.92 | 4.14 |

| Litoki | 6.87 | 6.20 | 6.69 | 7.00 | 4.76 | 3.67 | 4.58 | 4.73 | 6.31 | 5.44 | 6.15 | 6.38 | 6.68 | 6.43 | 5.90 | 6.86 | 6.05 | 5.77 | 5.60 | 6.36 |

| Mfourn | 6.12 | 4.97 | 6.06 | 6.18 | 5.53 | 5.09 | 5.32 | 5.73 | 5.42 | 5.20 | 5.00 | 5.84 | 5.46 | 5.10 | 4.60 | 5.66 | 4.72 | 4.53 | 4.35 | 5.02 |

| Liwaye | 3.53 | 3.18 | 3.08 | 3.81 | < 3 | / | / | / | < 3 | / | / | / | < 3 | / | / | / | < 3 | / | / | / |

| Poisson salé | 8.44 | 8.25 | 7.85 | 8.70 | 4.84 | 4.67 | 4.29 | 5.10 | 4.21 | 3.86 | 4.00 | 4.49 | 5.65 | 4.99 | 5.49 | 5.76 | 8.21 | 7.79 | 7.92 | 8.45 |

| Poisson fumé | 9.86 | 8.57 | 9.81 | 9.89 | 5.56 | 5.31 | 5.18 | 5.78 | 8.40 | 7.31 | 8.32 | 8.46 | 5.41 | 5.13 | 5.18 | 5.61 | 6.56 | 5.66 | 6.48 | 6.62 |

| a* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Atchrougou | 8.49 | 7.98 | 8.25 | 8.70 | 5.54 | 5.45 | 4.91 | 5.96 | 7.27 | 7.14 | 6.81 | 7.59 | 7.16 | 6.98 | 6.73 | 7.52 | 5.48 | 5.31 | 4.95 | 5.85 |

AMB aerobic mesophilic bacteria, M means, SD standard deviation, Min minimum, Max maximum, Und undetermined, CFU colony-forming units, a raw food, b cooked and ready-to-eat foods, c foods that can be eaten raw or cooked

Potential microbiological hazards of indigenous foods from Gabon

The most contaminated foods are Ayaga m’ombolo, Poisson fumé, Atchrougou followed by Poisson salé. The average microorganism load of Ayaga m’ombolo was respectively 11.96; 9.39; 7.48 and 5.76 log CFU/g of food for Aerobic Mesophilic Bacteria (AMB), Enterococcus, yeasts/moulds, and thermotolerant coliforms. The counts of microorganism carried out on Poisson fumé was respectively 9.86; 5.56; 8.40; 5.41 and 6.56 log CFU/g of food, while the average microbial load of Poisson salé was respectively 8.44; 4.84; 4.21; 5.65 and 8.21 log CFU/g of food for AMB, Bacillus, Enterococcus, yeasts/moulds, and thermotolerant coliforms. The number of AMB in Atchrougou was ranged between 8.25 and 8.70 log CFU/g of food; with an average of 8.49 log CFU/g of food. Similarly, the count of Bacillus, Enterococcus, yeasts/moulds, and thermotoclerant coliforms has given large loads for these foods samples.

A large load of microorganisms has also been found in indigenous foods samples such as Cassava dough use to Baton de manioc sampled before cooking, the Bogou, the Litoki,and the Mfourn, as well as cooked indigenous foods like Soukoutê or Ayaga mo'ombolo after cooking. These foods have shown high microorganism loads despite the heat treatment. After cooking, a load of AMB and Bacillus in Ayaga mo’ombolo remaine > 6.48 log CFU/g of food, loads of Enterococcus and yeasts/moulds decreased until 4.54 and 5.72 log CFU/g of food respectively, and the thermotolerant coliforms load has decreased to less than 3.0 log CFU/g of food. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in microbiological loads of cooked compared to uncooked Ayaga m’ombolo samples. The average AMB load of Soukoutê, a cooked dish from cassava leaves, was > 6.48 log CFU/g of food. The average microbial load of Bacillus, Enterococcus and yeast/moulds in Soukoutê was respectively 6.08; 3.65 and 3.84 log CFU/g of food, while the average of thermotolerant coliforms in Soukoutê was < 3.0 log CFU/g of food.

Lewaye's samples were the least contaminated with microorganisms. The number of AMB in Liwaye was ranged between 3.08 and 3.81 log CFU/g of food; with an average of 3.53 log CFU/g of food. The count of Bacillus, Enterococcus, yeasts/moulds, and thermotolerant coliforms has given load < 3.0 log CFU/g of food. High levels of microorganism particularly thermotolerant coliforms were detected in Ayaga m’ombolo before cooking, peanut butter (Litoki and Mfourn), Athrougou, Poisson salé, Poisson fumé, and Bogou. The microorganism enumeration results of these indigenous foods reflect the preliminary observation made during the monitoring, namely a lack of food safety.

The high loads of AMB are evidence of food alteration and a risk to consumer health. However, these microorganisms would play an important role during the manufacturing process regarding the organoleptic qualities of the food. Since women workers emphasized the value of certain steps in the process of indigenous foods, such as storing, soaking, ungutting fish, placing them in a brine tank or putting them in open air for hours or even days, this could indicate that it represents a so-called spontaneous natural fermentation according to the definition of "fermentation" of food technology field from the critical reviews papers of Tanasupawat and Visessanguan (2014) and Dimidi et al. (2019). In this way, this fermentation would be taken as a natural process in which the availability of nutrients and environmental conditions would allow the selection of particular micro-organisms whose action associated with endogenous food enzymes would create significant and desirable changes for food consumption. In this sense, spontaneous natural fermentation would require certain control in the order to have safe finished products, standardized with desired organoleptic qualities (Capozzi et al. 2017). In this study, the high thermotolerant coliforms loads provide information on poor hygiene during the manufacturing process of indigenous foods. The obtained results are in accordance with the data for indigenous foods from Africa countries (Odunfa and Oyewole. 1998; Bsadjo-Tchamba et al. 2015; Muandze-Nzambe et al. 2017). This can be justified on the one hand by the lack of Good Manufacturing Practice principles and on the other hand by the poor sanitation of environment around indigenous foods production sites.

Gabonese indigenous foods as a source of potential microorganisms for biotechnological use

In this study, high loads of Bacillus bacteria have been found in Ayaga mo’ombolo, Bogou, Poisson sale, and Poisson fumé. These bacteria have been found with antimicrobial and probiotic properties in many foods (Anyogu et al. 2014). In Congo-Brazzaville, studies have been carried out to select a potential multifunctional starter culture with Bacillus bacteria to control the production of Ntoba bodi, a cassava-leaves fermented food like Ayaga m’ombolo, in the order to deliver a product with improved nutritional and hygienic quality (Kayath et al. 2016). Given that these bacteria were widely found in indigenous foods of Gabon, further research is required to determine the extent to which these benefits are aligned with specific community needs. The work of Anyogu et al. (2014) provides information on the technical feasibility of studies on indigenous foods’ Bacillus impact. Nevertheless, an evaluation of the new or exciting Bacillus probiotics safety is recommended before their use for humans according to the studies of Ouoba et al. (2008).

Salmonella spp. presence

A total of 23 out of the 123 indigenous foods sampled were positive for Salmonella with an indigenous food prevalence of 18.69%. The sampled foods were considered contaminated when purified suspicious Salmonella colonies, from SS agar, triple sugar iron agar, lysine iron agar, and urea agar, were identified by API 20 E Gallery. Table 4 shows the occurrence of Salmonella positive indigenous foods and their traceability. Salmonella spp. were not detected in all foods that have undergone heat treatment, but also in Cassava dough used for the preparation of Baton de manioc and Atchrougou. However, Salmonella spp. were isolated from Ayaga m’ombolo before cooking to 8.33%, in Litoki to 33.33%; in Mfourn to 16.66%, in Poisson salé to 83.33% and Poisson fumé to 66.66%. The study provided the information on Salmonella spp. occurrence in indigenous foods samples following PCR confirmation by detection of invasion plasmid antigen B (IpaB) gene. The used IpaB primers were found to produce a 314-BP amplimer specific to Salmonella spp. among suspicious bacteria from API 20E Gallery, as shown in Fig. 5. This study carried out revealed that the occurrence of virulence gene IpaB was 13.01% among the 23 isolates of Salmonella spp. The results of our study indicate that indigenous foods would contribute to human exposure to Salmonella. Indeed, the Salmonella occurrence is high compared to the occurrence of IpaB virulence genes with 13.01% of indigenous foods samples from Gabon. This difference found can be attributed to the possible absence of this gene from these strains but also PCR specificity lessening the performance (sensitivity, specificity, false-negative rate, false-positive rate and accuracy). Currently, the invA gene appears as the best genes associated with virulence for the detection of Salmonella spp. (Deguenon et al. 2019; Yanestria et al. 2019). The use of Multiplex PCR methods including InvA, IpaB, spvR, SpvC, FimA or Stn genes in most diagnostic and research laboratories could be useful for descriptive epidemiological studies.

Table 4.

Occurrence of Salmonella positive indigenous foods and their source

| Foods samples | N | Percentage of sample test positively for Samonella presence (%) | Percentage of sample test positively for IpaB gene presence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ayaga m’ombolo before cooking | 6 | 1 (16.66%) | 1 (16.66%) |

| Ayaga m’ombolo after cooking | 6 | – | – |

| Atanga stick before heating | 9 | – | – |

| Atanga stick after heating | 9 | ||

| Soukoutê | 9 | – | – |

| Cassava dough before cooking | 24 | – | – |

| Litoki | 6 | 2 (33.33%) | 2 (33.33%) |

| Mfourn | 12 | 2 (16.66%) | 2 (16.66%) |

| Liwaye | 6 | – | – |

| Atchrougou | 12 | – | – |

| Poisson salé | 12 | 10 (83.33%) | 7 (58.33%) |

| Poisson fumé | 12 | 8 (66.66%) | 4 (33.33%) |

| Bogou | 12 | – | – |

| Total | 123 | 23 (18.69%) | 16 (13.01%) |

Fig. 5.

Electrophoresis analysis PCR-amplified target gene IpaB gene (314 bp), Legend. T + : Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC®14,028™), T- sterile distilled water, M size marker

Salmonella spp. are mostly used as markers of biological risk. The high Salmonella's occurrences found in this study is explained by the large occurrences found in the Poisson salé (83.33%) and the Poisson fumé (66.66%). These foods are unfit for human consumption without effective heat treatment before consumption. However, these extremely high occurrences would require confirmation as part of larger sampling. Traoré et al. (2015) and Yanestria et al.(2019) reported among the fish samples examined occurrences of 24% and 38.09% respectively. Observations of consumption behavior of Poisson salé and Poisson fumé by the Gabonese population indicating their potentials for raw consumption constitutes a health risk. It is the same with the consumption of peanut butter bread given the presence of Salmonella in 33.33% and 8.33% of Litoki and Mfourn samples respectively.

An unhealthy production environment may play a key role in the contamination of food during processing. Indeed, Salmonella bacteria can be excreted into the environment by human carriers or animals through stool. According to the work done by Sanchez et al.(2002), animals are a primary reservoir for nontyphoidal Salmonella associated with human infections, and contact with animal feces either directly through animal handling or manure or indirectly through fecal contamination of foods is principal vehicles of human infection. Fortunately, most food samples contaminated by Salmonella are systematically heat-treated before being consumed, specifically Ayaga m’ombolo, Poisson salé, and Poisson fumé. However, preventive measures during the cooking must be taken when handling these foods in order to limit cross-contaminations.

Also, this study showed that Salmonella could be present in ayaga m'ombolo before cooking but remain absent after cooking. Poisson salé and Poisson fumé haven’t been analyzed after cooking because they are condiments: they are used in small quantities in properly cooked dishes. The examined Soukoutê and Liwaye samples have been certified as free of Salmonella. Indeed, these foods have been packaged very hot after cooking. Furthermore, poor thermotolerant coliforms loads confirm the effectiveness of this heat-treatment. The Salmonella absence before heat treatment of Baton d’atanga, Athrougou, and Bogou, despite the no compliance of manufacturing process with GMP, could be explained by an incompatibility between necessary Salmonella growth factors and physicochemical parameters of food: their raw materials being oilseeds according to the study of Ondo-Azi et al. (2014). It is the same for cassava dough used for Baton de manioc where it is noted a low coliform charge and absence of Salmonella despite many lacks during the manufacturing process (Muandze-Nzambe et al. 2017). Physicochemical conditions of these foods would diverge with the growing requirements of Salmonella spp. These observations would require a more comprehensive approach for better understanding, especially since studies have demonstrated the potential for persistence of Salmonella bacteria in foods (He et al. 2011; Nummer et al. 2012). Based on the work of Nummer et al. (2012) the heat treatment effectiveness depends on the initial microbial load but also on the physicochemical composition of the food. Also, the large amounts of sucrose or fat would be favorable to the heat resistance of Salmonella.

Conclusion

Taken together our study revealed that indigenous foods of Gabon can be microorganism reservoirs due to the non-compliance of GMP but also that some factors of production are often difficult to control. Indeed, the microbiological tests have shown high thermotolerant coliforms loads in indigenous foods. The presence of salmonella in ready to eat food indicates potential effects on the health of consumers such as peanut butter (Mfourn or Litoki), Poisson salé and Poisson fumé. The women producers should be further educated and encouraged to take preventives measures to limit diarrheagenic bacterial pathogens and avoid cross contaminations. In the future, the use of functional cultures would be an interesting alternative for increasing the shelf life and ensuring the microbiological safety of some indigenous foods.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study grateful women who we are provided food which is carried in this study. We would thank CIRMF (Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville), for technical support and hosting this project in Gabon. The CIRMF is funded by the Gabonese government, Total-Fina-Elf Gabon and Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, France. Also, we would thank Melissa BERGER for reviewed this manuscript.

Author contributions

All of the authors contribute to this research. J.U.M.N was the principal investigator involved with this project; J.U.M.N., R.O., J.F.Y., J.F.M. and A.S. for conception and design of the work; J.U.M.N., R.O., J.F.Y., J.F.M. and A.S. for analysis and interpretation of data; J.U.M.N., H.C., N.S. C.Z. and A.S. for drafting the work and revising it critically for intellectual content. A.S. was responsible for the concept and preparation of final article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jean Ulrich Muandze-Nzambe, Email: milulrich@yahoo.fr.

Richard Onanga, Email: onangar@yahoo.com.

Jean Fabrice Yala, Email: yalalaw@yahoo.fr.

Namwin Siourimè Somda, Email: landsom60@yahoo.fr.

Hama Cissé, Email: cissehama70@gmail.com.

Cheikna Zongo, Email: zcheik@yahoo.fr.

Jacques Francois Mavoungou, Email: mavoungoujacques@yahoo.fr.

Aly Savadogo, Email: alysavadogo@gmail.com.

References

- Adejumo BA, Ola FA. The apparaisal of local food packaging materials in Nigeria. Cont J Eng Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anyogu A, Awamaria B, Sutherland JP, Ouoba LII. Molecular characterisation and antimicrobial activity of bacteria associated with submerged lactic acid cassava fermentation. Food Control. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bsadjo Tchamba G, Ibrahim Bawa H, Nzouankeu A, Bagre TS, Traoré AS, Barro N. Isolation, characterization and antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. isolated from local beverages («bissap», «gnamakoudji») sold in Ouagadougou Burkina Faso. Int J Biosci. 2015 doi: 10.12692/ijb/6.2.112-119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi V, Fragasso M, Romaniello R, Berbegal C, Russo P, Spano G. Spontaneous food fermentations and potential risks for human health. Fermentation. 2017 doi: 10.3390/fermentation3040049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deguenon E, Dougnon V, Lozes E, Maman N, Agbankpe J, Abdel-Massih RM, Djegui F, Baba-Moussa L, Dougnon J. Resistance and virulence determinants of faecal Salmonella spp. isolated from slaughter animals in Benin. BMC Res Notes. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidi E, Cox SR, Rossi M, Whelan K. Fermented foods : definitions and characteristics, gastrointestinal health and disease. Nutrients. 2019;11:1806–1831. doi: 10.3390/nu11081806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebuehi OAT, Oyewole AC. Effect of cooking and soaking on physical, nutrient composition and sensory evaluation of indigenous and foreign rice varieties in Nigeria. Nutr Food Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1108/00346650810847972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt J, Alabi AS, Kremsner PG, Rabsch W, Becker K, Foguim FT, Kuczius T, Esen M, Schaumburg F. Bacterial contamination of water samples in Gabon, 2013. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Les bonnes pratiques dhygiène dans la préparation et la vente des aliments de rue en Afrique. Rome: Division de linformation FAO; 2007. p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Guo D, Yang J, Lou TM, Zhang W. Survival and heat resistance of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in peanut butter. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/AEM.06270-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayath CA, Nguimbi E, Tchimbakala JG, Mamonékéné V. Towards the understanding of fermented food biotechnology in Congo Brazzaville. Adv J Food Sci Technol. 2016 doi: 10.19026/ajfst.12.3317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong RYC, Lee SKY, Law TWF, Law SHW, Wu RSS. Rapid detection of six types of bacterial pathogens in marine waters by multiplex PCR. Water Res. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(01)00503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muandze-Nzambe JU, Guira F, Cisse H, Zongo O, Zongo C, Djbrine AO, Savadogo A. Technological, biochemical and microbiological characterization of fermented cassava dough use to produce cassava stick, a Gabonese traditional food. Int J Multidiscip Curr Res. 2017;5:808–817. [Google Scholar]

- Nout R, Hounhouigan JD, Van Boekel T. Les aliments. Wageningen: Backhuys Publishers, Le Centre Technique de coopération Agricole et rurale (CTA); 2003. p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Nummer BA, Shrestha S, Smith JV. Survival of Salmonella in a high sugar, low water-activity, peanut butter flavored candy fondant. Food Control. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.11.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odunfa SA, Oyewole OB. African fermented foods. In: Wood BJB, editor. Microbiology of fermented foods. Boston, MA: Springer; 1998. pp. 713–752. [Google Scholar]

- Ondo-Azi AS, Ella Missang C, Nsikabaka S, Silou T, Chalchat JC. Variation in physicochemical and morphological characteristics of safou (Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) H. J. Lam) fruits: Classification and identification of elite trees for industrial exploitation. J Food, Agric Environ. 2014;12:212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ondo-Azi AS, Kumulungui BS, Mewono L, Mbina Koumba A, Ella Missang C. Proximate composition and microbiological study of five marine fish species consumed in Gabon. African J Food Sci. 2013 doi: 10.5897/ajfs12.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouoba LII, Thorsen L, Varnam AH. Enterotoxins and emetic toxins production by Bacillus cereus and other species of Bacillus isolated from Soumbala and Bikalga, African alkaline fermented food condiments. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Kwarteng J, Wuni A, Akabanda F, Jespersen L. Prevalence and Characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes Isolates in Raw Milk, Heated Milk and Nunu, a Spontaneously Fermented Milk Beverage, in Ghana. Beverages. 2018 doi: 10.3390/beverages4020040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pava-Ripoll M, Pearson REG, Miller AK, Ziobro GC. Prevalence and relative risk of Cronobacter spp., Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes associated with the body surfaces and guts of individual filth flies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/AEM.02195-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raufu IA, Ahmed OA, Aremu A, Odetokun IA, Raji MA. Salmonella transmission in poultry farms: The roles of rodents, lizards and formites. Savannah Vet J. 2019;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S, Hofacre CL, Lee MD, Maurer JJ, Doyle MP. Animal sources of salmonellosis in humans. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002 doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanni AI, Asiedu M, Ayernor GS. Microflora and chemical composition of Momoni, a Ghanaian fermented fish condiment. J Food Compos Anal. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S0889-1575(02)91063-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singla N, Thind RK, Mahal AK. Potential of eucalyptus oil as repellent against house Rat, Rattus rattus. Sci World J. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/249284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanasupawat S, Visessanguan W (2014) Fish fermentation. In Seafood Processing: Technology, Quality and Safety, Ioannis S. Boziaris, ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), Hoboken, pp. 177–207.

- Traoré O, Nyholm O, Siitonen A, Bonkoungou IJO, Traoré AS, Barro N, Haukka K. Prevalence and diversity of Salmonella enterica in water, fish and lettuce in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanestria SM, Rahmaniar RP, Wibisono FJ, Effendi MH. Detection of invA gene of Salmonella from milkfish (Chanos chanos) at Sidoarjo wet fish market, Indonesia, using polymerase chain reaction technique. Vet World. 2019 doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.170-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]