Abstract

Campylobacter, the most common etiologic agent of zoonotic gastroenteritis in humans, is present in many reservoirs including livestock animals, wildlife, soil, and water. Previously, we reported a novel Campylobacter jejuni strain SCJK02 (MLST ST-8388) from the gut of wild mice (Micromys minutus) using culture-dependent methods. However, due to fastidious growth conditions and the presence of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter spp., it is unclear whether M. minutus is a Campylobacter reservoir. This study aimed to: 1) determine the distribution and proportion of Campylobacter spp. in the gut microbiota of wild mice using culture-independent methods and 2) investigate the gut microbiota of wild mice and the relationship of Campylobacter spp. with other gut microbes. The gut microbiota of 38 wild mice captured from perilla fields in Korea and without any clinical symptoms (18 M. minutus and 20 Mus musculus) were analyzed. Metagenomic analysis showed that 77.8% (14 of 18) of the captured M. minutus harbored Campylobacter spp. (0.24–32.92%) in the gut metagenome, whereas none of the captured M. musculus carried Campylobacter spp. in their guts. Notably, 75% (6 of 8) of M. minutus determined to be Campylobacter-negative using culture-dependent methods showed a high proportion of Campylobacter through metagenome analysis. The results of metagenome analysis and the absence of clinical symptoms suggest that Campylobacter may be a component of the normal gut flora of wild M. minutus. Furthermore, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) showed that Campylobacter was the most enriched genus in the gut microbiota of M. minutus (LDA score, 5.37), whereas Lactobacillus was the most enriched genus in M. musculus (LDA score, −5.96). The differences in the presence of Campylobacter between the two species of wild mice may be attributed to the differential abundance of Campylobacter and Lactobacillus in their respective gut microbiota. In conclusion, the results indicate that wild M. minutus may serve as a potential Campylobacter reservoir. This study presents the first metagenomics analysis of the M. minutus gut microbiota to explore its possible role as an environmental Campylobacter reservoir and provides a basis for future studies using culture-independent methods to determine the role of environmental reservoirs in Campylobacter transmission.

Keywords: Campylobacter, wild mouse, Micromys minutus, environmental reservoir, gut microbiota, metagenomics, Lactobacillus, transmission cycle

Introduction

Campylobacter is one of the most common etiologic agents of zoonotic gastroenteritis in humans (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Although the most common cause of Campylobacter infection is the intake or handling of contaminated poultry, environmental sources such as wildlife, soil, and water are also important infection routes (Whiley et al., 2013; Hofreuter, 2014; Skarp et al., 2016). As an environmental reservoir, wildlife is an emerging source of Campylobacter infection via the direct transmission of Campylobacter to humans or indirectly via the wildlife-livestock-human cycle (Kim et al., 2020). While the majority of studies on Campylobacter reservoirs in wildlife have been conducted on wild birds, several studies on other hosts, such as deer, boars, and reptiles, have also been conducted (French et al., 2009; Díaz-Sánchez et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2013; Carbonero et al., 2014). Wild mice are distributed in a wide range of habitats globally and often transmit diverse zoonotic pathogens to humans and livestock, serving as a link between wildlife and the urban community (Razzauti et al., 2015); however, Campylobacter in wild mice is not well understood. One study reported Campylobacter strains isolated from wild rodents, suggesting wild rodents as a risk factor of Campylobacter infection in livestock (Meerburg et al., 2006).

Most studies on Campylobacter in wildlife have been conducted using culture-dependent methods, such as the isolation and characterization of bacterial strain (French et al., 2009; Díaz-Sánchez et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2013; Carbonero et al., 2014). Previously, we reported a novel C. jejuni strain SCJK02 (MLST ST-8388) isolated from fecal samples of wild mice (Micromys minutus) (Kim et al., 2020). In the previous study, Campylobacter was isolated from 63% of M. minutus, whereas none was isolated from Mus musculus. Considering the limitations of culture-dependent methods, such as fastidious growth conditions and the presence of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter spp. (Mihaljevic et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2009), it is likely that Campylobacter was not detected, even if it was present. Therefore, it is essential to apply culture-independent methods together with traditional culture-dependent methods to precisely determine the presence of Campylobacter in a host.

The role of the gut microbiota in Campylobacter-mediated infection has been reported in several studies (Li et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018). In humans, the microbiota of poultry workers infected with Campylobacter and those resistant to colonization of Campylobacter show significant differences in the abundance of certain genera (Dicksved et al., 2014). In laboratory mice, elevated levels of intestinal Escherichia coli reduce colonization resistance to Campylobacter (Haag et al., 2012), and the gut microbiota composition affects the extraintestinal dissemination of Campylobacter (O’Loughlin et al., 2015). In poultry, neonatal chickens transplanted with mature microbiota show a reduced transmission potential of Campylobacter (Gilroy et al., 2018). Thus, the infection risk of Campylobacter is affected by the gut microbiota of the host through diverse microbe-microbe interactions. Since the gut microbiota of M. minutus has not yet been investigated, studies are needed to improve the prediction and prevention of the transmission of Campylobacter from wildlife to humans.

This study was conducted to: 1) determine the distribution and proportion of Campylobacter spp. in the gut microbiota of wild mice using culture-independent methods and 2) investigate the core microbiota of wild mice and the relationship of Campylobacter spp. with other gut microbes. The gut microbiota of 38 wild mice without clinical symptoms (18 M. minutus and 20 M. musculus) and captured for 2 years from perilla fields in Korea at the end of winter torpor were analyzed. This study is the first to investigate the gut microbiota of M. minutus using metagenomics to explore its possible role as an environmental Campylobacter reservoir.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample Collection

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hallym University (approval number Hallym2017-5, Hallym 2018-6) approved this study. Two species of wild mice (M. minutus and M. musculus) were captured for 2 years from the perilla fields of Chuncheon in Korea at the end of their winter torpor. Information on the wild mice used in this study is included in the supplementary material ( Supplementary Table 1 ). All captured mice were transferred to the lab facility immediately. Fresh fecal samples from the mice were collected in single cages and stored at −80°C.

In our previous study, Campylobacter was isolated from mice fecal samples using two different culture methods (Kim et al., 2020). Briefly, homogenized fecal samples (in phosphate-buffered saline—PBS) were directly spread onto modified cefoperazone–deoxycholate agar plates (mCCDA; Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) containing the CCDA-selective supplement (Oxoid, Ltd.) and plates were incubated at 42°C for 2 days under microaerobic conditions. Next, Campylobacter-like colonies were inoculated into Müller–Hinton agar plates (Oxoid Ltd.) and then tested by Campylobacter genus-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Wang et al., 2002). All Campylobacter-positive colonies were identified as C. jejuni by species-specific PCR (Wang et al., 2002). Additionally, fecal samples that were Campylobacter-negative subjected to enrichment in Bolton broth (Oxoid, Ltd.) containing the Bolton broth selective supplement (Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) for 2 days at 42°C under microaerobic conditions. Thereafter, the presence of C. jejuni was investigated as above. Of note, results showed that Campylobacter was culture-positive in 63.6% of M. minutus, and culture-negative in all M. musculus.

Here, to investigate the differences in the gut microbiota of Campylobacter culture-positive and culture-negative M. minutus, 10 fecal samples from culture-positive M. minutus, and 8 fecal samples from culture-negative M. minutus were used for microbial community analysis. Additionally, to investigate the difference between the gut microbiota of the two wild mice species, 20 fecal samples from M. musculus (all Campylobacter culture-negative) were used for microbial community analysis.

DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Sequencing

Metagenomic DNA extraction from fecal samples was performed using the Fast DNA Soil Kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using the following primers: 341F; 5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′ and 805R; 5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′. PicoGreen was used to pool and normalize the amplified products. All sequencing processes were performed using an Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA) platform at Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, Korea).

Bioinformatics and Statistical Analyses

The bioinformatics analysis of the sequence data was performed using QIIME 2 (version 2019.10) software package (Bolyen et al., 2019) and MicrobiomeAnalystR in R package (Dhariwal et al., 2017). An amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table was generated by filtering, dereplicating, and denoising the raw sequence data using DADA2 (Callahan et al., 2016). A phylogenetic tree of representative sequences was generated using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Taxonomy assignment of the ASV table was conducted at the phylum and genus levels using a naïve Bayes classifier implemented in the q2-feature-classifier (Bokulich et al., 2018) against the SILVA database, version 132 (Quast et al., 2012). ASVs that were classified into the genus Campylobacter were further identified at the species-level. For downstream analysis, the sequencing data were normalized via rarefication to the minimum library size.

The alpha diversity of the microbial community was measured using the phyloseq package with two metrics, including the number of observed ASVs, which accounts for richness, and the Simpson’s and Shannon’s indexes, which account for richness and evenness (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). Differences in alpha diversity between wild mice groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. Beta diversity was measured based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, and the differences in beta diversity between wild mice groups were evaluated using the analysis of group similarities (ANOSIM) test. Sample core microbiota were defined as those with a minimum abundance of 0.01% and a prevalence of 50% as the cut-off values. Differential abundance analysis of microbiota was performed using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEFSe), implemented in MicrobiomeAnalystR in the R package (Segata et al., 2011). We considered a p value lower than 0.05 to indicate significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 3.6.3.

Results

Taxonomic Composition of the Gut Microbiota of Wild Mice

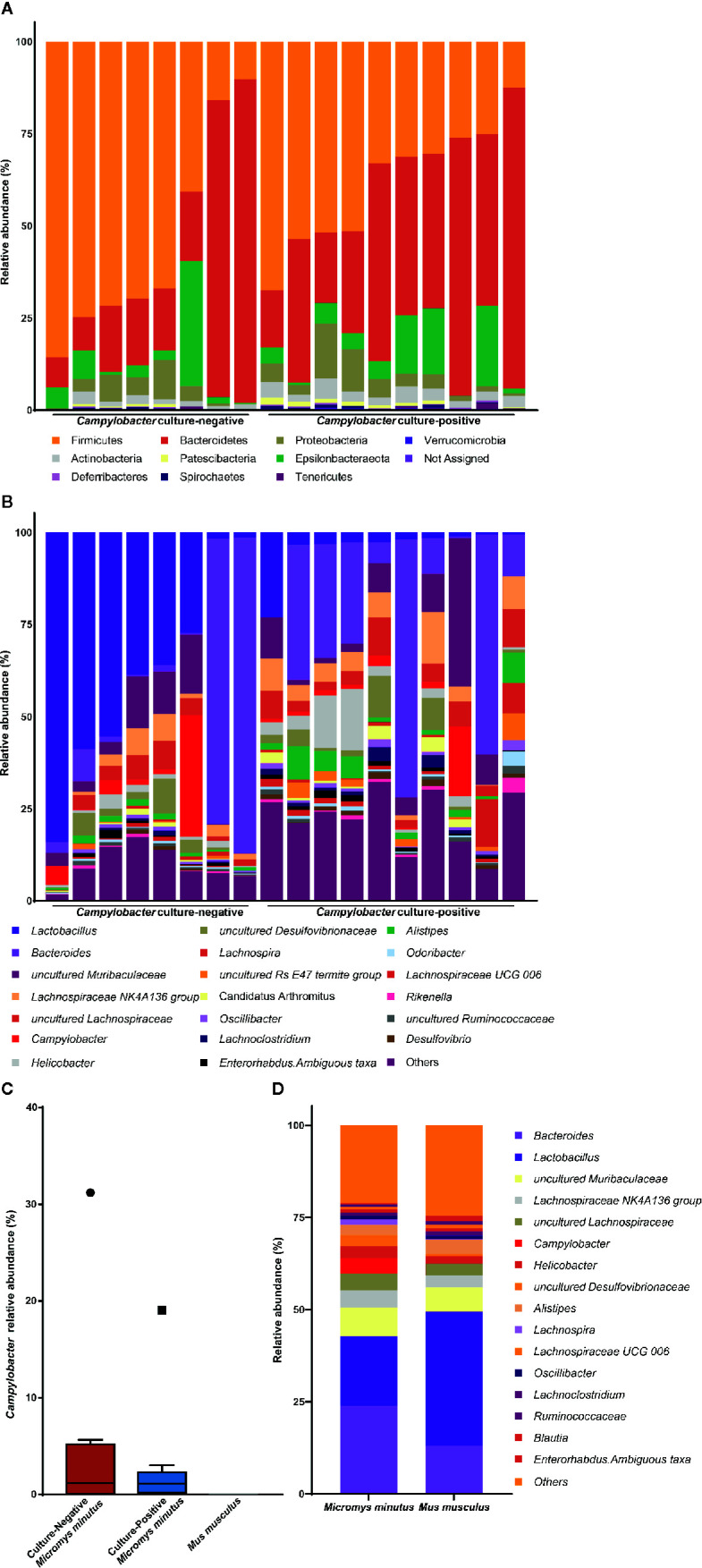

To determine the distribution and proportion of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota of wild mice, fecal microbiota from 18 M. minutus (10 culture-positive, 8 culture-negative) and 20 M. musculus (all culture-negative) were compared. No ASV was classified into the genus Campylobacter in the gut microbiota of M. musculus. The taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota of individual M. minutus at the phylum and genus levels are shown in Figures 1A, B . Campylobacter was present (0.24–32.92%) in the gut microbiota of 14 of 18 M. minutus (77.8%) but not in any of the M. musculus. The relative abundance of Campylobacter in the culture-positive and -negative groups of M. minutus showed no significant difference according to the Mann-Whitney U test (p > 0.05) ( Figure 1C ). Of note, all ASVs classified into the genus Campylobacter were identified as C. jejuni at the species-level.

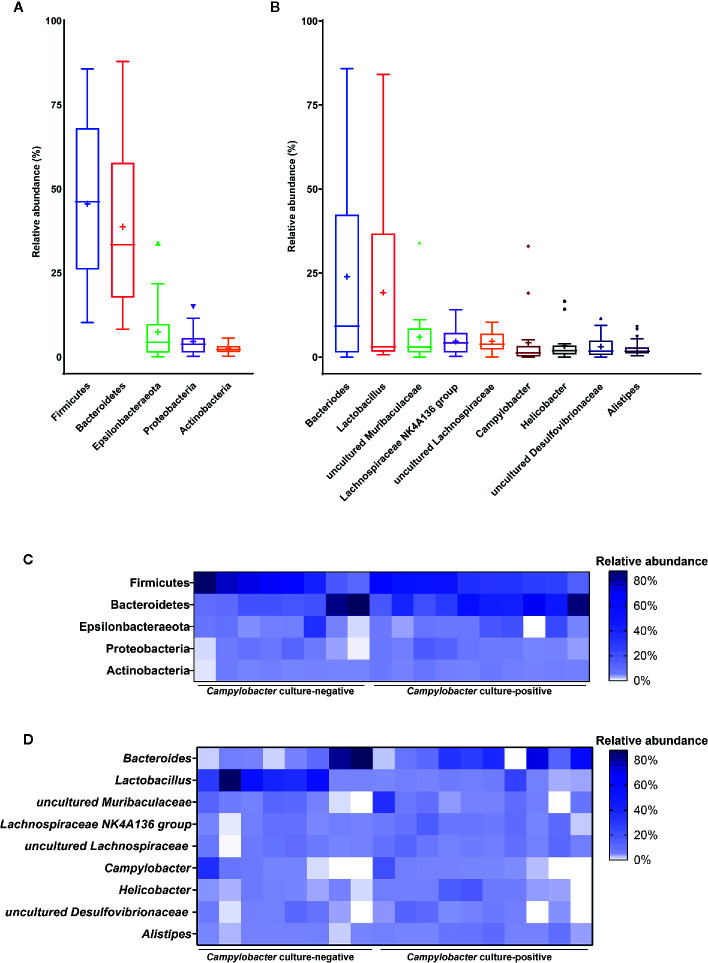

Figure 1.

Taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota of wild mice. Taxonomy bar plot of the gut microbiota of Micromys minutus at the (A) phylum and (B) genus levels. (C) The relative abundance of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota of Micromys minutus and Mus musculus. The blue and orange boxes represent the relative abundance of Campylobacter in the Campylobacter culture-positive and culture-negative M. minutus groups. Circle (●) and square (▪) represent the maximum point of relative abundance of Campylobacter, respectively. (D) Taxonomic composition of gut microbiota of two species of wild mice (Micromys minutus and Mus musculus) at the genus level.

The microbiota of all M. minutus samples comprised nine main bacterial phyla including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Epsilonbacteraeota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Patescibacteria, Deferribacteres, Spirochaetes, and Tenericutes. Firmicutes (45.47%) was the most dominant phylum, followed by Bacteroidetes (38.61%) and Epsilonbacteraeota (7.34%). At the genus level, Bacteroides (23.79%) was the most dominant genus, followed by Lactobacillus (18.92%), uncultured Muribaculaceae (5.96%), Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group (4.67%), uncultured Lachnospiraceae (4.65%), Campylobacter (4.03%), and Helicobacter (3.30%). The microbiota of M. musculus comprised seven main bacterial phyla, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Epsilonbacteraeota, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Patescibacteria, and Deferribacteres. Firmicutes (62.02%) was the most dominant phyla, followed by Bacteroidetes (32.70%) and Epsilonbacteraeota (2.00%). At the genus level, Lactobacillus (36.44%) was the most dominant genus, followed by Bacteroides (12.99%), uncultured Muribaculaceae (5.39%), and Alistipes (4.17%) ( Figure 1D ). The taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota of individual M. musculus is shown in Supplementary Figure 1 .

Members of the core microbiota of M. minutus at the phylum level were identified as Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Epsilonbacteraeota, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria ( Figures 2A, C ). Members of the core microbiota of M. minutus at the genus level were identified as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, uncultured Muribaculaceae, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, uncultured Lachnospiraceae, Helicobacter, Campylobacter, uncultured Desulfovibrionaceae, and Alistipes ( Figures 2B, D ).

Figure 2.

Core gut microbiota of Micromys minutus. Box plots showing the relative abundance of the members of the core microbiota at the (A) phylum and (B) genus levels. Plus sign (+) represents the mean value. Heatmaps showing the relative abundance of core microbiota (C) at the phylum and (D) genus levels in individual M. minutus samples. The X-axis represents the individual samples of M. minutus. The Y-axis represents the core taxa. The color scale represents the relative abundance of core taxa in individual samples.

Differences in the Gut Microbiota of Micromys minutus According to the Culture Results of Campylobacter

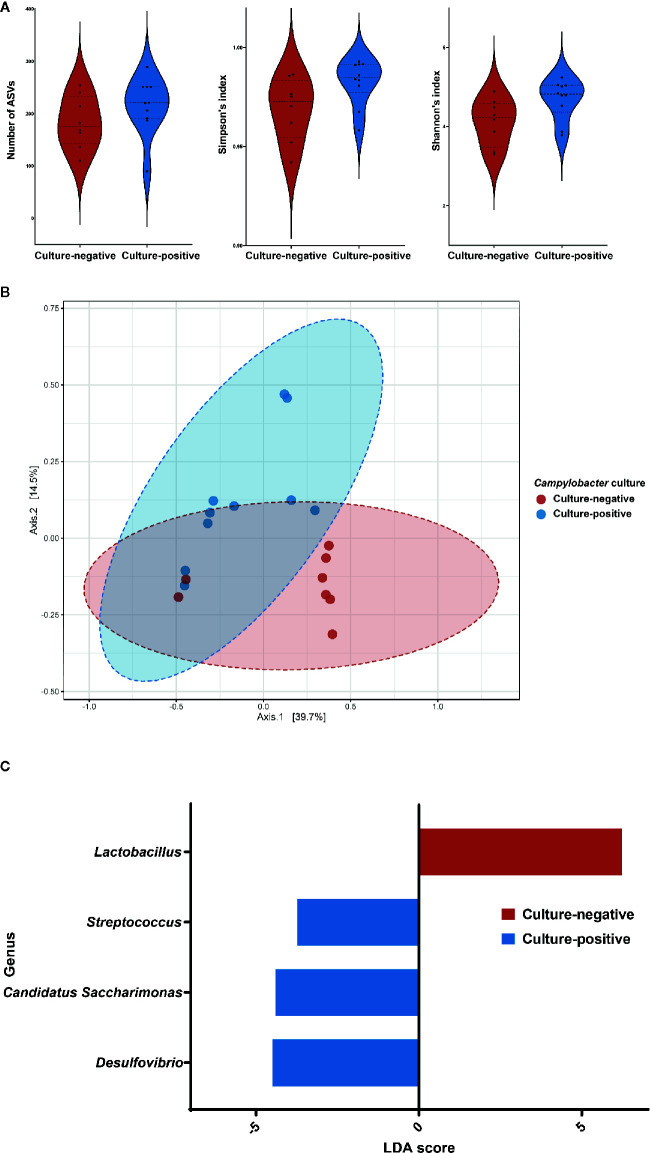

When the two culture groups of M. minutus were compared using the Mann-Whitney test, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in the number of observed ASVs, the Simpson’s index and the Shannon’s index ( Figure 3A ).

Figure 3.

Differences in the gut microbiota of Micromys minutus according to Campylobacter culture status. (A) Alpha diversity of the gut microbiota of two groups of Micromys minutus. The distribution of the number of observed amplicon sequence variants, the Simpson’s index and the Shannon’s index of each group is shown in the box plot. The blue box denotes the Campylobacter culture-positive group, and the red box denotes the Campylobacter culture-negative group. (B) Principle coordinate analysis plot of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between the gut microbiota of the Campylobacter culture-negative and -positive groups of M. minutus. Ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals. (C) Histograms of the linear discriminant analysis scores for genera with differential abundance identified using linear discriminant analysis effect size in a culture-positive (blue) and culture-negative (red) group of Micromys minutus.

The beta diversity as per the principle coordinate analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity showed distinct clustering of the gut microbiota of M. minutus according to the Campylobacter culture results ( Figure 3B ). An ANOSIM test revealed a significant difference in the gut microbiota between the Campylobacter culture-positive and -negative groups of M. minutus (R: 0.23253, p < 0.05). Of note, no significant differences in the beta diversity of the M. minutus groups were detected for other factors, such as gender and habitat (p > 0.05).

To identify the bacterial taxa with significantly different abundances between wild mice groups, LEFSe was performed. When the Campylobacter culture-positive and negative groups of M. minutus were compared at the phylum level, Actinobacteria (LDA score −4.89, p < 0.05) was the most enriched phylum in the microbiota of Campylobacter culture-positive M. minutus, followed by Patescibacteria (LDA score −4.4, p < 0.05). At the genus level, Lactobacillus (LDA score 6.23, p < 0.05) was the most enriched genus in the microbiota of Campylobacter culture-negative M. minutus, whereas Desulfovibrio (LDA score −4.5, p < 0.05), Candidatus Saccharimonas (LDA score −4.4, p < 0.05), and Streptococcus (LDA score −3.73, p < 0.05) were enriched in Campylobacter culture-positive M. minutus ( Figure 3C ).

Difference in the Gut Microbiota Between Two Species of Wild Mice

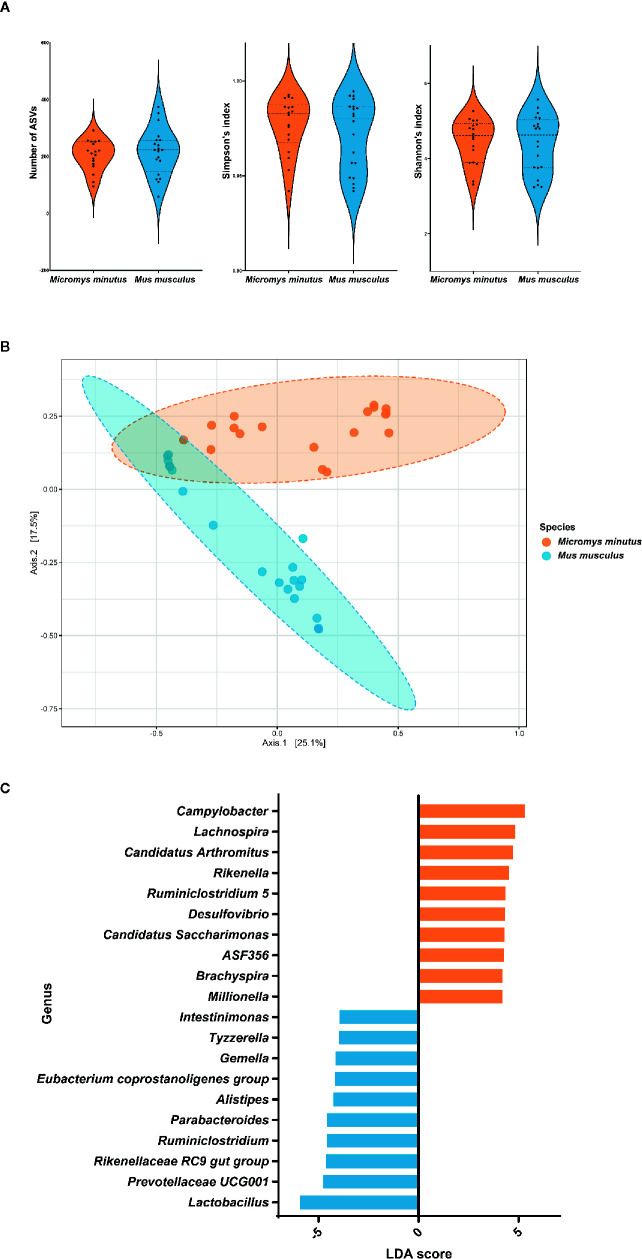

When the alpha diversity of two species of wild mice (M. minutus and M. musculus) was compared using the Mann-Whitney test, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in the alpha diversity metrics, including the number of observed ASVs, the Simpson’s index, and the Shannon’s index ( Figure 4A ).

Figure 4.

Differences in the gut microbiota of two species of wild mice. (A) Alpha diversity of the gut microbiota of two species of wild mice. The distribution of the number of observed amplicon sequence variants, the Simpson’s index and the Shannon’s index of each group is shown in the box plot. (B) Principle coordinate analysis plot of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between the gut microbiota of Micromys minutus (orange) and Mus musculus (blue). Ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals. (C) Histograms of the linear discriminant analysis scores for genera with differential abundance identified using linear discriminant analysis effect size in M. minutus (orange) and M. musculus (blue).

The beta diversity as per the principle coordinate analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity showed distinct clustering of the gut microbiota of wild mice according to species ( Figure 4B ). An ANOSIM test revealed a significant difference in the gut microbiota between M. minutus and M. musculus (R: 0.57627, p < 0.001).

When the two species of wild mice (M. minutus and M. musculus) were compared, the abundance of eight phyla, including Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, Deferribacteres, Spirochaetes, Patescibacteria, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Epsilonbacteraeota were found to be significantly different (p < 0.05) based on LEFSe. Firmicutes (LDA score −5.92) was the most enriched phylum in the gut microbiota of M. musculus, whereas Epsilonbacteraeota (LDA score 5.43) was the most enriched phylum in the gut microbiota of M. minutus, followed by Proteobacteria (LDA score 5.19), Actinobacteria (LDA score 4.69), Patescibacteria (LDA score 4.3), Spirochaetes (LDA score 4.2), Deferribacteres (LDA score 3.96), and Verrucomicrobia (LDA score 3.35). At the genus level, the abundance of all 35 genera was significantly different (p < 0.05). Campylobacter (LDA score 5.3) was the most enriched genus in M. minutus, whereas Lactobacillus (LDA score −5.94) was the most enriched genus in M. musculus ( Figure 4C , Supplementary Table 2 ).

Discussion

Previously, we reported a novel C. jejuni strain isolated from wild M. minutus using a culture-dependent method (Kim et al., 2020). However, the incrimination of M. minutus as a reservoir based on culture-dependent methods alone remained unclear because of difficulties in the isolation of Campylobacter owing to the fastidious growth conditions required (i.e., microaerophilic) and the presence of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter (Mihaljevic et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2009). Moreover, numerous studies have highlighted the role of a reservoir’s microbiota composition in the transmission of a wide range of zoonotic pathogens (Jones et al., 2008; Stecher et al., 2013; Razzauti et al., 2015). However, most studies on the microbiota of wild mice have focused on that of wild M. musculus, belonging to the same species as the laboratory mouse, and no study has investigated the microbiota of M. minutus (Weldon et al., 2015; Rosshart et al., 2017; Rosshart et al., 2019). Therefore, it is essential to investigate the gut microbiota of M. minutus using a culture-independent method to predict the role of M. minutus in Campylobacter transmission.

The current study revealed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the most dominant phyla in the gut microbiota of M. minutus; in fact, these are the dominant phyla in a wide range of wild rodents (Debebe et al., 2017; Lavrinienko et al., 2018) and are involved in nutrition metabolism and the immune response of the host (Tremaroli and Bäckhed, 2012). Members of Firmicutes play key roles in the degradation of polysaccharides (Flint et al., 2012); thus, the high abundance of Firmicutes in the gut may be related to the food sources and habitats of M. minutus (Hata, 2011). At the genus level, Bacteroides and Lactobacillus were the predominant genera, accounting for nearly half of the microbiota composition. The high abundance of Bacteroides and Lactobacillus is consistent with the results of another study on omnivorous mammals, including wild mice (Apodemus sylvaticus), bears, squirrels, and lemurs (Maurice et al., 2015). The next dominant genera were uncultured Muribaculaceae, which is a major component of the mouse gut microbiota and a member of the family Muribaculaceae, which was previously known as the S24-7 group (Lagkouvardos et al., 2019), and Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, a short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria in the gut (Hu et al., 2019). Therefore, the components of the gut microbiota of M. minutus appear to be comparable to those of the gut microbiota of wild rodents reported in previous studies.

Notably, Campylobacter was the sixth most abundant genus in the microbiota of all M. minutus and varied among samples; this high abundance is inconsistent with previous studies on the microbiota of wild mice (Maurice et al., 2015; Weldon et al., 2015; Rosshart et al., 2017; Rosshart et al., 2019). Moreover, most M. minutus harbored Campylobacter in their gut metagenome. Of note, this high prevalence of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota is similar to that in poultry, which is known to harbor Campylobacter as part of the normal gut flora (O’Sullivan et al., 2000; Sahin et al., 2002; Humphrey, 2006). Moreover, the concept of core microbiota considers not only the abundance but also the prevalence to identify microbial communities that exist persistently (Shade et al., 2012; Astudillo-García et al., 2017); thus, Campylobacter appears to be a member of the core microbiota of the gut of M. minutus. Furthermore, when laboratory mice are infected with Campylobacter, clinical signs of campylobacteriosis, such as a ruffled coat, hunched posture, lethargy, and diarrhea are observed (Stanfield et al., 1987; Mansfield et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2018). Therefore, if the high abundance and prevalence of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota of M. minutus were due to an external infection, there would have been clinical signs of campylobacteriosis in M. minutus; however, no clinical signs were observed in any captured mice. Considering the results of metagenome analysis and the absence of clinical signs, Campylobacter may exist as a normal component of the gut microbiota of M. minutus.

The core microbiota of M. minutus contained taxa that, in previous studies, were shown to be members of the microbiota of wild mice (A. sylvaticus) and laboratory mice, such as Alistipes (Maurice et al., 2015) and uncultured Desulfovibrionaceae (Zhang et al., 2010). Notably, Helicobacter, which can infect humans and other hosts (Bagheri et al., 2015; Tohidpour, 2016) is also a member of the core microbiota of M. minutus. Previous studies suggested wild mice (M. musculus molossinus and A. sylvaticus) as a reservoir of diverse Helicobacter strains according to culture-dependent (Won et al., 2002) and culture-independent methods (Maurice et al., 2015); however, the possibility of M. minutus as a potential reservoir of other zoonotic pathogens has not been studied. Future studies using culture-dependent methods for further analyses, such as the isolation and characterization of pathogens, are needed to explore the potential of wild mice as a reservoir of other zoonotic pathogens.

Metagenomic analysis results showed that most of the captured M. minutus harbored Campylobacter in the gut metagenome, regardless of their culture status. Notably, most M. minutus that were determined to be Campylobacter-negative by culture-dependent methods harbored high proportions of Campylobacter in the gut metagenome, indicating that culture-dependent methods alone cannot reliably indicate whether Campylobacter is present in the gut. This may be attributed to difficulties in the isolation of Campylobacter (as mentioned above) or the cultivation of Campylobacter may have been affected by components of the gut microbiota, such as competing flora that inhibit the growth of Campylobacter (Jasson et al., 2009; Hazeleger et al., 2016). Moreover, the difference in the microbiota composition between the culture-positive and -negative groups may have affected the isolation of Campylobacter. Beta diversity analysis, which showed that the microbiota of M. minutus was clustered by the Campylobacter culture results rather than by other factors such as gender or habitat, supported this possibility. Differential abundance analysis showed that Lactobacillus was the only significantly enriched genus in the culture-negative group compared to that in the culture-positive group. Previous studies revealed that the growth of Campylobacter in co-cultures of Campylobacter and Lactobacillus was significantly lower than that in a single culture of Campylobacter, indicating that Lactobacillus acts as an antagonist to reduce the level of Campylobacter in culture (Wang et al., 2014; Taha-Abdelaziz et al., 2019). These results support the possibility that the relatively high abundance of Lactobacillus in the culture-negative group affected the isolation of Campylobacter during the culture procedures. As studies on the characteristics of Lactobacillus strains isolated from wild mice are lacking, further studies are needed to better understand the antagonistic activities of wild mice-derived Lactobacillus strains on Campylobacter.

The presence of Campylobacter in the gut of the two species of wild mice was also very distinctly different by species. Most M. minutus harbored Campylobacter in their gut, whereas none of the M. musculus harbored Campylobacter in their gut. Notably, the presence of Campylobacter differed remarkably, despite the fact that the two species of mice were captured in adjacent areas. These results suggest that the different microbiota composition of the two species of wild mice may affect the colonization of Campylobacter in the gut. Recent studies showed that components of the gut microbiota provide colonization resistance to Campylobacter by competing for nutrition, by modulating the host immune response, and through direct antagonism (Neish, 2009; O’Loughlin et al., 2015; Kampmann et al., 2016); thus, the components of the microbiota in wild M. musculus may have prevented the colonization of Campylobacter in their gut. Differential abundance analysis to identify significantly enriched taxa in M. musculus showed that Lactobacillus was the most enriched genus in M. musculus. Diverse Lactobacillus strains are known to reduce the colonization of Campylobacter in the gut (Alemka et al., 2012; Sicard et al., 2017); thus, highly abundant Lactobacillus may have played a role as a prophylactic agent against Campylobacter in the gut of M. musculus. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the interaction of the gut microbiota and colonization of Campylobacter in wild mice.

Conclusion

This study is the first to investigate the gut microbiota of M. minutus using metagenomics to explore its possible role as an environmental Campylobacter reservoir. This culture-independent approach indicated that wild M. minutus may serve as a reservoir of Campylobacter. Metagenomic analysis results revealed that most M. minutus harbored high proportions of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota regardless of culture status, indicating the necessity of using a culture-independent method together with traditional culture-dependent methods to precisely determine the presence of Campylobacter. Considering the high abundance and prevalence of Campylobacter in the gut microbiota, and the absence of clinical symptoms, Campylobacter may be a component of the normal gut flora of wild M. minutus. These findings provide a basis for future studies on the role of environmental reservoirs in the transmission cycle of Campylobacter using culture-independent methods.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA656071.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hallym University.

Author Contributions

SC conceived and designed the study. HS, JK, and J-HG performed the sampling and experiments. HS, WK, and HN analyzed the data. JGS and JKS prepared and reviewed the manuscript. HS made a great contribution to the experiments, data analysis, and preparing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-234 2018R1A2B6002396) and the Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (2014M3A9D5A01075129 and 2016M3A9D5A01952417) of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.596149/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alemka A., Corcionivoschi N., Bourke B. (2012). Defense and adaptation: the complex inter-relationship between Campylobacter jejuni and mucus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 15. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astudillo-García C., Bell J. J., Webster N. S., Glasl B., Jompa J., Montoya J. M., et al. (2017). Evaluating the core microbiota in complex communities: A systematic investigation. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 1450–1462. 10.1111/1462-2920.13647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri N., Azadegan-Dehkordi F., Shirzad H., Rafieian-Kopaei M., Rahimian G., Razavi A. (2015). The biological functions of IL-17 in different clinical expressions of Helicobacter pylori-infection. Microb. Pathog. 81, 33–38. 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N. A., Kaehler B. D., Rideout J. R., Dillon M., Bolyen E., Knight R., et al. (2018). Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6, 90. 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen E., Rideout J. R., Dillon M. R., Bokulich N. A., Abnet C. C., Al-Ghalith G. A., et al. (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan B. J., McMurdie P. J., Rosen M. J., Han A. W., Johnson A. J. A., Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonero A., Paniagua J., Torralbo A., Arenas-Montes A., Borge C., García-Bocanegra I. (2014). Campylobacter infection in wild artiodactyl species from southern Spain: Occurrence, risk factors and antimicrobial susceptibility. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37, 115–121. 10.1016/j.cimid.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debebe T., Biagi E., Soverini M., Holtze S., Hildebrandt T. B., Birkemeyer C., et al. (2017). Unraveling the gut microbiome of the long-lived naked mole-rat. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-017-10287-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal A., Chong J., Habib S., King I. L., Agellon L. B., Xia J. (2017). MicrobiomeAnalyst: A web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W180–W188. 10.1093/nar/gkx295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Sánchez S., Sánchez S., Herrera-León S., Porrero C., Blanco J. E., Dahbi G., et al. (2013). Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. in large game animals intended for consumption: Relationship with management practices and livestock influence. Vet. Microbiol. 163, 274–281. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicksved J., Ellström P., Engstrand L., Rautelin H. (2014). Susceptibility to Campylobacter infection is associated with the species composition of the human fecal microbiota. MBio 5, e01212-14. 10.1128/mBio.01212-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H. J., Scott K. P., Duncan S. H., Louis P., Forano E. (2012). Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes 3, 289–306. 10.4161/gmic.19897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French N. P., Midwinter A., Holland B., Collins-Emerson J., Pattison R., Colles F., et al. (2009). Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from wild-bird fecal material in children’s playgrounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 779–783. 10.1128/AEM.01979-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy R., Chaloner G., Wedley A., Lacharme-Lora L., Jopson S., Wigley P. (2018). Campylobacter jejuni transmission and colonisation in broiler chickens is inhibited by Faecal Microbiota Transplantation. bioRxiv 476119. 10.1101/476119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haag L.-M., Fischer A., Otto B., Plickert R., Kühl A. A., Göbel U. B., et al. (2012). Intestinal microbiota shifts towards elevated commensal Escherichia coli loads abrogate colonization resistance against Campylobacter jejuni in mice. PLoS One 7, e35988. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata S. (2011). Nesting Characteristics of Harvest Mice (Micromys minutus) in Three Types of Japanese Grasslands with Different Inundation Frequencies. Mammal Study 36, 49–53. 10.3106/041.036.0106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeleger W. C., Jacobs-Reitsma W. F., de H. M. W. (2016). Quantification of growth of Campylobacter and extended spectrum β-lactamase producing bacteria sheds light on black box of enrichment procedures. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1430. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofreuter D. (2014). Defining the metabolic requirements for the growth and colonization capacity of Campylobacter jejuni . Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 137. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Wang J., Xu Y., Yang H., Wang J., Xue C., et al. (2019). Anti-inflammation effects of fucosylated chondroitin sulphate from: Acaudina molpadioides by altering gut microbiota in obese mice. Food Funct. 10, 1736–1746. 10.1039/c8fo02364f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T. (2006). Are happy chickens safer chickens? Poultry welfare and disease susceptibility. Br. Poult. Sci. 47, 379–391. 10.1080/00071660600829084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. N., Davis B., Tirado S. M., Duggal M., Van Frankenhuyzen J. K., Deaville D., et al. (2009). Survival mechanisms and culturability of Campylobacter jejuni under stress conditions. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 96, 377–394. 10.1007/s10482-009-9378-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasson V., Sampers I., Botteldoorn N., López-Gálvez F., Baert L., Denayer S., et al. (2009). Characterization of Escherichia coli from raw poultry in Belgium and impact on the detection of Campylobacter jejuni using Bolton broth. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 135, 248–253. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. E., Patel N. G., Levy M. A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J. L., et al. (2008). Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993. 10.1038/nature06536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush N. O., Castaño-Rodríguez N., Mitchell H. M., Man S. M. (2015). Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 687–720. 10.1128/CMR.00006-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampmann C., Dicksved J., Engstrand L., Rautelin H. (2016). Composition of human faecal microbiota in resistance to Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 61.e1–61.e8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Guk J. H., Mun S. H., An J. U., Kim W., Lee S., et al. (2020). The Wild Mouse (Micromys minutus): Reservoir of a Novel Campylobacter jejuni Strain. Front. Microbiol. 10, 3066. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagkouvardos I., Lesker T. R., Hitch T. C. A., Gálvez E. J. C., Smit N., Neuhaus K., et al. (2019). Sequence and cultivation study of Muribaculaceae reveals novel species, host preference, and functional potential of this yet undescribed family. Microbiome 7, 1–15. 10.1186/s40168-019-0637-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrinienko A., Mappes T., Tukalenko E., Mousseau T. A., Møller A. P., Knight R., et al. (2018). Environmental radiation alters the gut microbiome of the bank vole Myodes glareolus. ISME J. 12, 2801–2806. 10.1038/s41396-018-0214-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Quan G., Jiang X., Yang Y., Ding X., Zhang D., et al. (2018). Effects of metabolites derived from gut microbiota and hosts on pathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 314. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Ma R., Wang Y., Zhang L. (2018). The Clinical Importance of Campylobacter concisus and Other Human Hosted Campylobacter Species. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 243. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield L. S., Patterson J. S., Fierro B. R., Murphy A. J., Rathinam V. A., Kopper J. J., et al. (2008). Genetic background of IL-10–/– mice alters host–pathogen interactions with Campylobacter jejuni and influences disease phenotype. Microb. Pathog. 45, 241–257. 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice C. F., Cl Knowles S., Ladau J., Pollard K. S., Fenton A., Pedersen A. B., et al. (2015). Marked seasonal variation in the wild mouse gut microbiota. ISME J. 9, 2423–2434. 10.1038/ismej.2015.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie P. J., Holmes S. (2013). Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One 8, e61217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerburg B. G., Jacobs-Reitsma W. F., Wagenaar J. A., Kijlstra A. (2006). Presence of Salmonella and Campylobacter spp. in wild small mammals on organic farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 960–962. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.960-962.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaljevic R. R., Sikic M., Klancnik A., Brumini G., Mozina S. S., Abram M. (2007). Environmental stress factors affecting survival and virulence of Campylobacter jejuni . Microb. Pathog. 43, 120–125. 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neish A. S. (2009). Microbes in Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Gastroenterology 136, 65–80. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J. L., Samuelson D. R., Braundmeier-Fleming A. G., White B. A., Haldorson G. J., Stone J. B., et al. (2015). The intestinal microbiota influences Campylobacter jejuni colonization and extraintestinal dissemination in mice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4642–4650. 10.1128/AEM.00281-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan N. A., Fallon R., Carroll C., Smith T., Maher M. (2000). Detection and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in broiler chicken samples using a PCR/DNA probe membrane based colorimetric detection assay. Mol. Cell. Probes 14, 7–16. 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Gilbert M. J., Blaser M. J., Tauxe R. V., Wagenaar J. A., Fitzgerald C. (2013). Human infections with new subspecies of Campylobacter fetus . Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 1678–1680. 10.3201/eid1910.130883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., et al. (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596. 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzauti M., Galan M., Bernard M., Maman S., Klopp C., Charbonnel N., et al. (2015). A comparison between transcriptome sequencing and 16S metagenomics for detection of bacterial pathogens in wildlife. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, 1–21. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosshart S. P., Vassallo B. G., Angeletti D., Hutchinson D. S., Morgan A. P., Takeda K., et al. (2017). Wild Mouse Gut Microbiota Promotes Host Fitness and Improves Disease Resistance. Cell 171, 1015–1028.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosshart S. P., Herz J., Vassallo B. G., Hunter A., Wall M. K., Badger J. H., et al. (2019). Laboratory mice born to wild mice have natural microbiota and model human immune responses. Science (80-.) 365, eaaw4361. 10.1126/science.aaw4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin O., Morishita T. Y., Zhang Q. (2002). Campylobacter colonization in poultry: sources of infection and modes of transmission. Anim. Heal. Res. Rev. 3, 95–105. 10.1079/ahrr200244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N., Izard J., Waldron L., Gevers D., Miropolsky L., Garrett W. S., et al. (2011). Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shade A., Hogan C. S., Klimowicz A. K., Linske M., McManus P. S., Handelsman J. (2012). Culturing captures members of the soil rare biosphere. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2247–2252. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02817.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard J. F., Bihan G., Vogeleer P., Jacques M., Harel J. (2017). Interactions of intestinal bacteria with components of the intestinal mucus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 387. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarp C. P. A., Hänninen M. L., Rautelin H., II (2016). Campylobacteriosis: The role of poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 103–109. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield J. T., McCardell B. A., Madden J. M. (1987). Campylobacter diarrhea in an adult mouse model. Microb. Pathog. 3, 155–165. 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90092-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Berry D., Loy A. (2013). Colonization resistance and microbial ecophysiology: using gnotobiotic mouse models and single-cell technology to explore the intestinal jungle. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 793–829. 10.1111/1574-6976.12024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Winglee K., Gharaibeh R. Z., Gauthier J., He Z., Tripathi P., et al. (2018). Microbiota-Derived Metabolic Factors Reduce Campylobacteriosis in Mice. Gastroenterology 154, 1751–1763.e2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha-Abdelaziz K., Astill J., Kulkarni R. R., Read L. R., Najarian A., Farber J. M., et al. (2019). In vitro assessment of immunomodulatory and anti-Campylobacter activities of probiotic lactobacilli. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–15. 10.1038/s41598-019-54494-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohidpour A. (2016). CagA-mediated pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori . Microb. Pathog. 93, 44–55. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremaroli V., Bäckhed F. (2012). Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 489, 242–249. 10.1038/nature11552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Clark C. G., Taylor T. M., Pucknell C., Barton C., Price L., et al. (2002). Colony Multiplex PCR Assay for Identification and Differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp fetus . J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 4744 LP – 4747. 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4744-4747.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhao Y., Tian F., Jin X., Chen H., Liu X., et al. (2014). Screening of adhesive lactobacilli with antagonistic activity against Campylobacter jejuni . Food Control 44, 49–57. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.03.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weldon L., Abolins S., Lenzi L., Bourne C., Riley E. M., Viney M. (2015). The gut microbiota of wild mice. PLoS One 10, 1–15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiley H., van den Akker B., Giglio S., Bentham R. (2013). The role of environmental reservoirs in human campylobacteriosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 5886–5907. 10.3390/ijerph10115886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won Y. S., Yoon J. H., Lee C. H., Kim B. H., Hyun B. H., Choi Y. K. (2002). Helicobacter muricola sp. nov., a novel Helicobacter species isolated from the ceca and feces of Korean wild mouse (Mus musculus molossinus). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209, 43–49. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhang M., Wang S., Han R., Cao Y., Hua W., et al. (2010). Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. ISME J. 4, 232–241. 10.1038/ismej.2009.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA656071.