Abstract

A novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is an acute life-threatening disease, emerged in China, which imposed a potentially immense toll in terms of public health emergency due to high infection rate and has a devastating economic impact that attracts the world’s attention. After that, on January 30, 2020, it was officially declared as a global pandemic by World Health Organization (WHO). The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recognized it as a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease named Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19). Several studies have been ameliorated the active role of COVID-19 transmission, etiology, pathogenicity, and mortality rate as serious impact on human life. The symptoms of this disease may include fever, fatigue, cough and some peoples are severely prone to gastrointestinal infection. The elderly and seriously affected peoples are likely concerned with serious outcomes. In this review, we mainly aimed to provide a benchmark summary of the silent characteristics and findings of some candidates for antiviral drugs and immunotherapies such as plasma therapy, cytokine therapy, antibodies, intravenous immunoglobulin, and pharmaceutical health concerns that are related to this disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, Origin, SARS-CoV-2, Transmission, Clinical characteristics, Pharmaceutical services, Diagnosis

1. Introduction

Novel-Coronavirus-2019 (2019-nCoV) belongs to a large family of coronaviruses (CoVs), which mainly affect the respiratory system of human-beings and produced pneumonia-like symptoms. It is an acute life-threatening disease to human life. The first outbreak of CoVs began in 2003, which caused Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). The second outbreak started in 2013, known as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) (Bogoch et al., 2020, Burke and report, 2020; Lu et al., 2020). The third emergence of this outbreak of infectious etiology in late December 2019. And it has been given the name ‘Coronavirus Disease −2019’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Zhao et al., 2020). At this time, the epicenter of the outbreak emerged from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The virus is easily transmitted from animals to humans through the seafood market in every province of China.

Following is the chronological timeline of the novel COVID-19:

Initially, the first case of novel COVID-19 was reported in late December 2019, during the emergence within two months, and after that fifty thousand cases were reported globally (Du Toit, 2020). In China, five active cases were reported between 18 29 December, and out of only one patient died (Ren et al., 2020). It was also predicted that the virus spread in those patients that were nosocomial, hospital-acquired, and concluded that the transmission from human to human is less likely; instead, the virus is spread to these patients through unknown mechanisms. By January 22, 2020, 571 cases were reported in various districts and cities of 25 different provinces of China (Lu, 2020).

On the same date, 17 affected patient’s deaths from COVID-19 were reported by China National Health Commission. Furthermore, on January 25, 2020, the number of confirmed cases and deaths in China was reported about 1975 and 56, respectively (Wang et al., 2020d, Wang et al., 2020e, Wang et al., 2020f). Another study revealed that on January 24, 2020, 5502 active cases in China were reported. (Nishiura et al., 2020), and the ratio of these cases were actively raised to 7734 by January 30, 2020, furthermore, the other countries include USA, Germany, France, Japan, Australia, Finland, India, and UAE, etc., reported the confirmed cases through COVID-19 infection. The estimated fatality rate was 2.2% reported by (Bassetti et al., 2020). The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the USA was reported on January 20, 2020 (Holshue et al., 2020), followed by first case on January 30, 2020, which was reported from human-to-human transmission. (https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0130). The CDC started screening the passengers arriving in the USA. This initial screening then started to state vise screening of people in 41 different states of USA, 15(3.1%) out of 443 people were confirmed positive. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov). On February 7, 2020, there were 31,161 confirmed cases, and 630 were confirmed deaths in China were reported. (http://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00154.

Pandemics are progressively alarming a constant threat to human life, of these COVID-19 becoming the recent example that attracts the world’s population around the globe (Hâncean et al., 2020; Perc et al., 2020). The outbreak of the second-wave also found a forthcoming menace to human society and also showed destructive subsidies on the economical stage (Cacciapaglia et al., 2020). The term “Second wave” not only ameliorate the state of seasonal variation or consecutive cycle of COVID-19 infection, but it initiates and spread from the first-wave. The three assumptions of the “second wave” should be noticed in a couple of days, weeks, and months as (1) a revive in medical necessities, (2) the significant strategies in-terms of intermediate COVID-19 disease (3) and a health frontline burnout (Argulian, 2020). The current review mainly enlightens the recent strategies, health services, and research findings, mainly: epidemiology, mode of transmission, pathogenesis, antiviral drugs, pharmaceutical services, and research progression of rapidly eradicating the COVID-19 infection across the world.

2. Epidemiology

On March 3, 2020, according to the WHO report, there were 87,317 confirmed cases, out of which 2977 (3.42%) had died from this disease. Of these total cases, only China had 79,968 (92%) active cases and 2873 (96.5%) mortalities rate. While there were only 7169 cases, had been reported in 59 different countries. The number of active cases in different countries vary because of their atmospheric conditions. (Cascella et al., 2020). Table 1 represented the comparison of the epidemiological features of SARS-CoVs, COVID-19, and MERS-CoVs, respectively.

Table 1.

Timeline features of coronaviruses (CoVs).

| Facts |

MERS |

SARS |

COVID-19 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Radius |

>1 |

2–5 |

2.68 |

|

| Incubation period | 5.2 days | 4.6 days | 6.4 days | |

| Host | •Natural | Bats | Chinese horseshoe bats | Bats |

| •Intermediate | Dromedary Camels | Masked palm Civets | Pangolin | |

| •Terminal | Human | Human | Human | |

| Transmission | •Human To Human (Via Fomites, Physical Contact, Aerosol Droplets) •Nosocomial •Zoonotic •Fecal-Oral |

•Human to Human (Via Aerosol Droplets) •Fecal-Oral •Zoonotic •Nosocomial •Opportunistic Airborne |

•Limited Human to Human (Aerosol Droplets) •Nosocomial •Zoonotic •Respiratory |

|

3. Etiology

Coronavirus belongs to ran viruses. These viruses feeds the animals hence they are the animal’s hosts (Chen et al., 2020b). Because of the crown-like appearance observed under an electron microscope, they are called coronaviruses (Cascella et al., 2020). There are three families of coronaviruses, namely Arteriviridae, Roniviridae, and Coronaviridae (Chen et al., 2020b). Furthermore, there are four genera of Coronaviridae family; alpha, beta, delta, and gamma coronaviruses, respectively (Cascella et al., 2020). While the genera of the beta coronavirus have five lineages (Chan et al., 2013). The genetic source of alpha and beta CoVs suggested that the rodents and bats are their reservoirs. On the other hand, the delta and gamma CoVs have reservoirs in birds (Cascella et al., 2020).

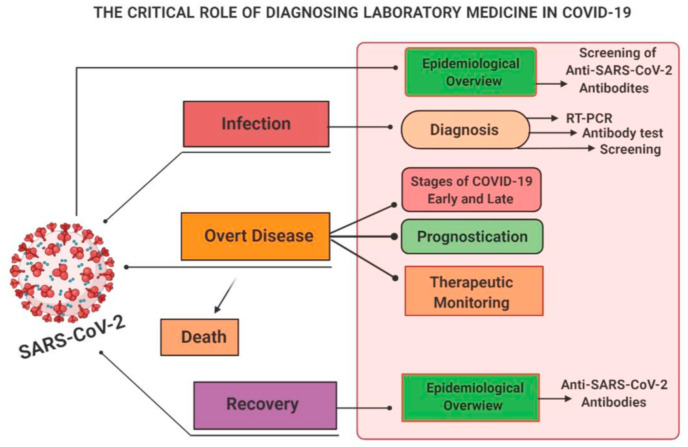

Coronaviruses affect the major organs of the human body like respiratory, hepatic, gastrointestinal, and nervous systems, respectively. While 5–10% of the infected cases severely affected the respiratory system. It was also estimated that only 2% of people were healthy carriers (Chen et al., 2020b). The variants of the coronaviruses such as HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, and HCoV-229 E are commonly found in human viruses. In immunocompromised and older people, they might affect the lower respiratory tract while in healthy persons, they deactivated themselves without causing any problems. While the novel coronaviruses, including the SARS-CoVs, MERS-CoVs, and COVID-19, can affect the upper and lower respiratory system as well as they also affect the other systems of the human body (Cascella et al., 2020). The schematic representation demonstrates the critical role and the medical surveillance of COVID-19 infection as summarized in (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The critical role of diagnosing laboratory medicine in COVID-19.

COVID-19 is a beta-like coronavirus that has 99% genomic similarity with pangolin genome and 96% similarity with the viruses like CoVZXC21 present in the bats genome. (Chan et al., 2020a; Chen et al., 2020b). It also has an 82% nucleotide resemblance with human SARS (Chan et al., 2020a). The genomic length of the virus ranges from 29, 89–29, 903 nucleotides. The virus shows sensitivity towards heat and ultraviolet radiation (Cascella et al., 2020). The viral proteins can also be killed by 60% ethanol, 75% ether, and chlorine-containing disinfectants, respectively.

4. Clinical characteristics

COVID-19 is highly contagious, and it can easily spread and transmits through droplets during talking, sneezing, coughing, and direct contact with the affected area (Lee et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020b), it can also be transmitted by fecal route too (Zhang et al., 2020). It enters the cell after binding with its receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme2 (ACE2). This receptor is abundantly integrates into the human respiratory tract (Hamming et al., 2004) The incubation period of COVID-19 starts in the human body, after the consists of infection within 1–14 days, and it’s becoming more contagious during this period of the life cycle (Jin et al., 2020b). Severely affected groups are the elderly and the ones who have already been suffering from any other disease. Mostly the people who were affected by the virus are in between 47 and 59 years old. Of all these cases, 42–46% of the infected patients were females (Guan et al., 2020b; Li et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2020a).

The common symptoms include high-grade fever, cough, and body aches (Poutanen et al., 2003). In children, it may cause flu-like symptoms. And people who become severely ill suffer from shortness of breath, respiratory distress syndrome, and respiratory failure, respectively. Additionally, due to the lack of oxygen supply, most of the organs of the body failed and lead to death of the patient (Huang et al., 2020a).

5. Symptoms

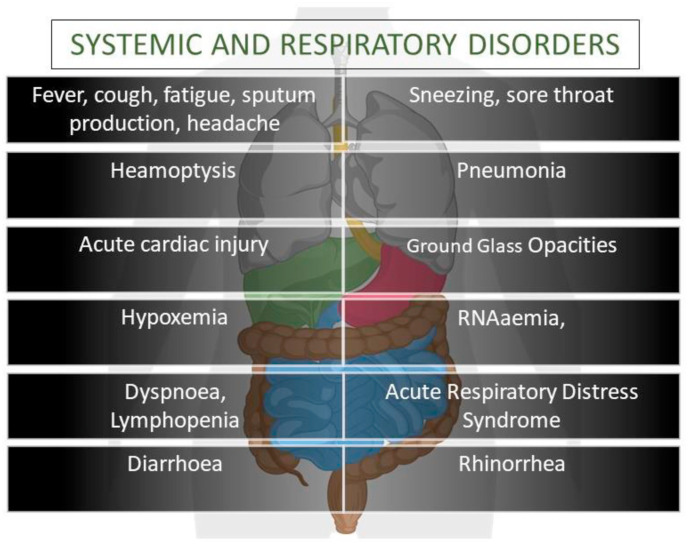

The symptoms appeared after the incubation period of 5 days during the infection(Li et al., 2020b). The period from onset death in between 6 and 41 days (median = 14days). The mentioned period is influenced by the age and immune system of the affected patient. Therefore, the higher the age usually 70 or above, the shorter will be period, and vice versa (Wang et al., 2020d). Common symptoms of COVID-19 that appeared at the onset are hyperthermia, dry cough (when an infection is in the upper respiratory tract), and myalgia, respectively. Other symptoms include diarrhea, headache, dyspnea, and lymphopenia, respectively. The schematic representation of systematic and respiratory disorders is shown in (Fig. 2 ). The productive cough starts when the infection reaches the lower respiratory tract (Carlos et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020a; Ren et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020d). CT scan of COVID-19 patients showed pneumonia-like clinical characteristics, but other facets cause fatality, namely: acute respiratory distress syndrome, anemia, acute heart injury, and occurrence of grand-glass opacities, respectively (Huang et al., 2020a).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of systematic and respiratory disorders of COVID-19 patient.

In some of the COVID-19 cases, it has been observed that pleural and sub-pleural regions of the affected lungs were occupied with numerous peripheral ground-glass opacities, which were the indication of inflammation of the regions where the immune response to the body was weak. Unfortunately, the use of inhalational interferons worsens the condition instead of showing any improvement in the symptoms (Lei et al., 2020). The patient suffering from beta viruses showed similar symptoms like fever, dry cough, shortness of breathing, and bilateral ground-glass opacities on the chest observed by Computer tomography scan (Huang et al., 2020a).

But the COIVD-19 shown some of the unique features when compared with other congeners because it may not only affects the upper respiratory tract but also severely affected the lower respiratory tract (Chan et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2020b). Furthermore, the chest X-ray revealed that the virus causes infiltration in the upper lobe of the lungs. That is the reason why the patient suffers from dyspnea and hypoxemia (Phan et al., 2020). The person affected by COVID-19 and its previous congeners SARS and MERS showed similar GI symptoms though they are less pronounced in the later ones. Therefore, the fecal route of transmission, and the testing of feces and urine is also important (Lee et al., 2003; Assiri et al., 2013), because it will not only help in the formulation of transmission control strategies but also for the development of the active drugs for this virus.

6. Transmission of COVID-19

Since the start of the pandemic, every new day gives more and more information the virus. In the following sections, we have summarized the latest and updated reports regarding virus transmission while mainly focusing on the three basic modes of transmission from the people who were infected with the virus. They include symptomatic, pre-symptomatic, and asymptomatic people, respectively.

6.1. Symptomatic transmission

Symptomatic, as the name suggests, is the condition in which the persons are experiencing the symptoms of the disease. And in symptomatic transmission, the virus moves from an infected person to a healthy person. Various epidemiological and virologic studies have been shown that the main mode of virus transmission was spread from the symptomatic people to healthy people who were in close contact with each other. And the mode of transmission was easily transmitted either by direct contact, using contaminated objects, and or through the respiratory droplets of an infected people (Burke and report, 2020; Chan et al., 2020b; Huang et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2020a; Ong et al., 2020; Organization, 2020a).

Furthermore, it has been found that in the initial phase (first three days after onset) of the viral infection, there is more shedding of virion in the nose and throat (Lauer et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2020e; Wolfel et al., 2020). This usually happens within three days after the onset of the symptoms (Liu et al., 2020b; Wolfel et al., 2020). This is the period in which the infected people are more contagious than the later phase of the infection.

6.2. Pre-symptomatic transmission

During the incubation period, the person is in the pre-symptomatic phase has also mild symptoms of infection. So, the transmission of the virus can also occur in this phase as well. Tracing of contacts and investigation of the confirmed cases has been proved helpful in the documentation of such kind of transmission of the virus (Huang et al., 2020b; Kimball et al., 2020; Ling and Leo, 2020; Pan et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). The mode of transmission is also the same as transmission from an asymptomatic person.

6.3. Asymptomatic transmission

It is the transmission of the virus from an infected person who doesn’t has any progressive symptoms at all. It’s less documented because few reported cases were positive COVID-19 but showed no symptoms. Due to the limitation of the reports and evidence, the potential of this mode of transmission cannot be excluded (Organization, 2020a; Wei et al., 2020).

7. Pathogenesis of COVID-19

As the infected persons infected with COVID-19, SARS, and MERS show similar symptoms like fever, dry cough, shortness of breathing, muscle pain, tiredness, and pneumonia, respectively so the exact pathogenesis is not understood properly. But the similar mechanisms for SARS and MERS can help us to differentiate between them from COVID-19 infection (Peiris et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2020a).

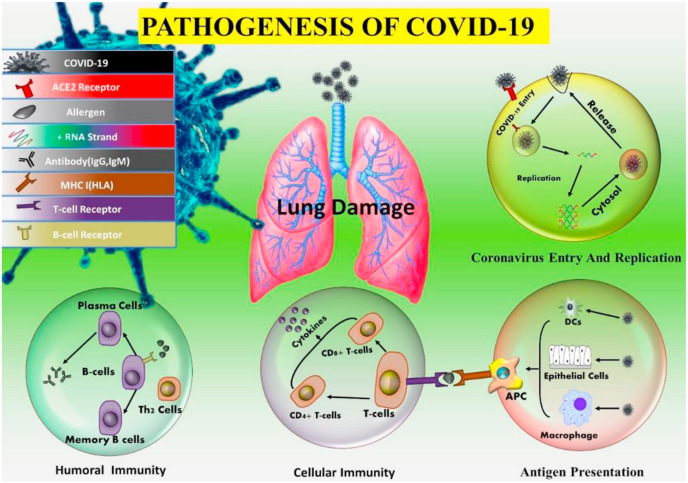

7.1. Coronavirus entry and replication

Coronavirus enters the cell surface by using its spike-like protein (De Wit et al., 2016), which binds with angiotensin receptor 2 (ACE2). COIVD-19 (Li et al., 2003b) and SARS both use the same receptor (Wu et al., 2020b). While SARS uses CD209L for entry into the cell (Jeffers et al., 2004). On the other hand, MERS uses dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) for entry (Raj et al., 2013). After attachment with the receptor, the virus directly integrates into the plasma membrane from the cell surface. (Simmons et al., 2004). A study conducted by (Belouzard et al., 2009) has shown that the integration of virus through membrane has done by viral spike-like protein, which after integration convert into a specific proteolytic phase of cleavage. In comparison, MERS follows a two-step membrane fusion but abnormal furin activation has done in this pathway (Millet and Whittaker, 2014). SARS also uses clathrin-independent and -dependent endocytosis to enter into the cell (Wang et al., 2008; Kuba et al., 2010).

After entering the cell, the virus releases its genome into the cytoplasm. Then as the result of translation, two structural and two poly-proteins of the virus are formed, which then lead to viral replication in the cell (Perlman and Netland, 2009). Thus, the envelop formed from glycol-proteins are transported to the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus. At the same time genomic RNA and nucleocapsid proteins combined to form nucleocapsid. Finally, the germination of virions takes place into the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC), and thus the vesicles containing virions fused with the plasma membrane to release the virus (De Wit et al., 2016).

7.2. Antigen presentation in coronavirus infection

As soon as the virus enters the cell, some of its peptides are cut by the cellular enzymes, and then these peptides are presented as an antigen on the surface of the cell such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which play an ambient role in immunity. The antigens that are presented on the surface of the cell by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in humans, known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA). In the case of COVID-19, we still do have sufficient data to understand its pathogenesis by antigen presentation. However, we can get some insights from the MERS and SARS pathogenesis mechanisms. In the case of SARS, MHCI molecules play a major role in antigen presentation, while MHCII also has some contribution. Various polymorphs of HLA, namely HLA-B∗0703, HLA-B∗4601, HLA-DR B1∗1202 (Keicho et al., 2009), and HLA-Cw∗0801 (Chen et al., 2006) showed susceptibility towards SARS. On the other hand, alleles of HLA-A∗0201, HLA-Cw1502, and HLA-DR0301 have a protective role against SARS infection (Wang et al., 2011). While MHCII molecules such as HLA-DQB1∗02:0 and HLA-DRB1∗11:01 play a role in susceptibility in MERS infection. (Hajeer et al., 2016). And in SARS cases, gene polymorphisms of mannose-binding lectin (MBL), associated with antigen presentation, enhanced the chances of infection through the virus (Tu et al., 2015).

7.3. Humoral and cellular immunity

As soon as the antigen is binds on the surface of the infected cell, it is recognized by the B and T cells of the immune system to provide humoral and cellular immunity. These cells of the immune system are specific to the virus. Like the response of the body to other viruses in the case of SARS to IgM and IgG are produced. IgM antibodies, which are specific for SARS have a short half-life of 12 weeks as compared to IgG antibodies. Thus, the IgG antibodies play a prominent role in protection from the virus (Li et al., 2003a). While the SARS-specific antibodies have N-specific and S-specific antibodies (De Wit et al., 2016).

More work has been done on the cellular modes of immunity as compared to humoral immunity. Recently it has been reported that in the peripheral blood of the patients suffering from COVID-19, the level of CD$4+ and CD8+ T cells is significantly decreased. In the case of SARS infection, the level of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was decreased to a greater extent. And the CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells can survive for about four years in the patients who were recovered from the infection. These memory T cells could increase, produce interferon-alpha, and give DTH response, respectively (Fan et al., 2009).

Besides this, when the recovered patients of SARS infection were tested for memory T-cells, their presence was still found in 14 out of 23 patients (Tang et al., 2011). In mice who was infected with MERS showed a similar response as shown by specific CD4+ (Zhao et al., 2014). The above information may help in the development of a vaccine against COVID-19.

7.4. Cytokine storm in COVID-19

The fatality in COVID-19 patients was mainly caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Like 6 out of 41 earlier patients had died off due to ARDS (Huang et al., 2020a). SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 all have the same immune-pathological event, i.e., ARDS (Xu et al., 2020b). In the case of SARS, ARDS is the result by cytokine storm, which is a fatal uncontrollable systemic response of the immune system in which pro-inflammatory cytokines [interferons (alpha, gamma), interleukin (1,2,12,18,33), tumor Necrosis factor-alpha, tumor growth factor-beta, etc.) and chemokine’s (CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL8, CXCL9, CXCL10, etc.), respectively are released from the cells of the immune system to produce a strong immune response against repelling the virus out of the human body (Cameron et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2014; Channappanavar and Perlman, 2017; Huang et al., 2020a). In the case of severing MERS, the serum level of IL-6, IFN alpha, and chemokines (CCL5, CXCL8, and CXCL-10) are being increased to a high level as compared to mild and moderate infection (Min et al., 2016). The same cytokine storm takes place in COVID-19 as it has also been occurred in SARS and MERS. Finally, the person succumbs because of hypoxemia followed by multiple organ dysfunction and failure (Xu et al., 2020b).

7.5. Coronavirus immune evasion

To protect from the immune reaction of the host, SARS and MERS utilized various strategies. Normally the viruses have pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which help in the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), but SARS and MERS produced double-layer vesicles that don’t have PRRs. Thus, the host becomes unable to detect their double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (Snijder et al., 2006). Interferon’s (alpha and beta) give protection to SARS and MERS infection, but experiments on infected mice revealed that the interferon pathway was blocked (Channappanavar et al., 2016, 2019). In MERS, accessory protein 4a may inhibit the initiation of interferons; this happens through direct interaction of dsRNA of the virus at the level of MDA5 activation. Furthermore, open reading frame [ORF(4a,4 b,5)] proteins and membranous proteins of MERS blocked nuclear transportation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and activation of the interferon-beta promoter (Yang et al., 2013).

Furthermore, MERS infection decreases the ability of the cell to produce such proteins that play a role in antigen binding mechanism (Menachery et al., 2018). Thus, halting the ability of the COVID-19 to circumvent the immune system of the host by following different modes of replications are presented in (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Pathogenesis of COVID-19. a) Coronavirus attacking the lungs. b) Coronavirus entry and replication inside the host’s cells. c) Antigen-presenting cell (APC) presenting the antigen to the surface of the T lymphocyte. d) Cytokine storm which causes multiple organ failure.

8. Principles of IPC (infection prevention control) strategies associated with health care

To achieve proper and adequate protection from the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevention and control against the infection under the supervision of the government and the facility management must be in place, which ensures the application of the strategies and practices discussed in the coming section (Organization, 2020c). Furthermore, in the countries where either the IPC is absent or if present but with limited scope, then it is mandatory to fulfil the minimum requirements for it (Organization, 2020d).

Following are the strategies of the IPC to minimized the transmission in healthcare setups:

-

1

Triage establishment (order of treatment), early detection, isolation of suspected patients

-

2.

For suspected patients ensuring contact and airborne precautions

-

3.

Employing standard precautions for all the persons in the facility

-

4.

Administrative control

-

5.

Engineering and environmental control

8.1. Ensuring triage, early recognition, and source control

Triage consists of a system in which the assessment and then isolation of the suspected patients in a separate area is done to control the transmission of the infection.

For early identification of the suspects, the health care setups should follow:

-

•

Establish a triage with the proper equipment and the trained staff

-

•

Encourage the health care team to have a good understanding of the symptoms of the suspected patients

-

•

Place signs in public places so that HCT can easily recognize the symptomatic patients.

-

•

Establish the use of updated questionnaires to screen the patients.

-

•

Promote hand and respiratory hygiene because they are effective to measure the control and spread of viral infection

- •

8.2. Applying standard precautions for all patients

Standard precautions include hand and respiratory hygiene because they are useful measures to control the spread of the viral infection. Additionally, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), safe waste management, appropriate linens, injection safety practices, and cleaning and sterilization of all the equipment used in the care of the patients.

Following respiratory hygiene must be advised to all the patients:

-

•

After every contact of the hand with the surfaces, the hand must be washed

-

•

When a person has to cough or sneeze, then he covers it either with his elbow or tissue paper

-

•

Provide mask to suspected COVID-19 patients.

My 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene is a WHO approach, which every person on the health care team must follow. Hand hygiene must be performed: when and after touching a patient, before performing any procedure, after exposure to the contaminated fluids of the patients, and after direct contact with the things present near the patient.

The following are the two approaches for hand hygiene.

-

•

When hands are dirty, and the dust is visible, then hands must be washed with water and soap

-

•

If hands are not dirty enough, then alcohol-based hand sanitizer can be used.

PPE must be used according to the need, and supply also plays an effective role in decreasing virus transmission. The effectiveness of PPE depends upon its availability, enough staff training, hand hygiene, and the human attitude towards the effective usage of the supplies (Organization, 2008, 2014). The management of medical supplies, medical waste, culinary utensils, and laundry, respectively must be done according to the standard safety procedures (Organization, 2014, 2016).

9. Diagnostic criteria

Initially, in China, the virus was viewed under an electron microscope, and its morphological characteristics were observed accordingly. Now, the nasal and throat sample is collected through a cotton swab, and then they are subjected to analysis by a real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Lu et al., 2020).

10. Community pharmacy (pharmacist) service during the COVID-19 pandemic

Community pharmacy is the health care setup that provides prescription medications, over the counter medications, supplements, and other healthcare-related products and services, respectively. The scope of coverage of services varies from country to country. For example, the scope and definition of community pharmacy are different in China than the western countries. In the USA and UK, community pharmacy includes retail pharmacies with or without branches and outpatient pharmacies, which are located in the hospital. However, in China, the concept of community pharmacy is entirely different than the entire world, i.e., the community pharmacies are only located in health care facilities. Such pharmacies are bound to follow the orders of local and national governments. Furthermore, in china, community pharmacies are not considered part of the health care system rather, they are regulated by the companies that own them. And the personnel working in such pharmacies are not considered health care professionals (Zheng et al., 2020).

10.1. Special needs of PC services during the COVID-19 pandemic

The scope of community pharmacy and pharmacist is different from normal circumstances. This scope is divided into two objectives, namely prevention and control of pandemic and addressing the pharmacy-related issues of the patients. For effective control, the patients have to be screened in the pharmacy, and the suspected ones are then referred to as a designated facility for treatment (Zheng et al., 2020). They must be educated and trained enough in personal protection skills so that they can easily minimize the transmission of virus (Organization, 2020b; Zheng et al., 2020). The patients who are either in isolation or suffering from mild COVID-19 don’t have enough guidance regarding the self-care strategies at home (Zheng et al., 2020).

There are similarities to the needs of traditional and community patients, but their paradigm of focus is different. When providing, for example, consultation to community patients, then their questions are more COVID-19 oriented than usual medications. They will ask about the necessary information related to COVID-19, such as signs and symptoms, prevention strategies, and masks selection, etc. The patients with chronic disease of a community that is quarantined are at more risk to the shortage of drug supply, and eventually, poor or non-compliance would be the result. In these circumstances, the community, pharmacists can play influential roles to fulfill the needs of the community.

10.1.1. Pharmacy management

It is the responsibility of the community pharmacy management team to effectively plan and perform its operation according to the aspects of their needs and demands of the infected patients.

10.1.2. Ensure an adequate supply of medications and products for COVID-19 prevention

During a pandemic, the provision of daily medications (disease-specific and OTC) and COVID-19 preventive supplies (masks and alcohol-based hand sanitizers) to the patients is solely on community pharmacies because for the public these are the easily accessible options (Zheng et al., 2020). Drug supply for chronic patients of the other disease can be assessed by the drug purchase and delivery services. By employing the potentials of the internet, the location of the pharmacies and availability of the medications and other relevant supplies can be announced and delivered online. Secondly, via mobile applications, the patients can be guided when they need medications.

At the time of the pandemic, home services can be provided by the pharmacies to decreased the chances of virus transmission. Home deliveries can be done by coordinating with social workers, volunteers, and drug companies, respectively. Chinese community pharmacies successfully achieved medication provided to the community by the aforementioned collaborative approach. Instantaneously for quarantined people, they collaborated with the nearby community staff to provide the medication to such confined people. And on the other hand, to supply the medications to the patients who were suffering from chronic diseases such as cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, etc. they worked with the pharmaceutical companies to ensure the medication supply to such patients (Hangoma et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020c).

11. Pharmaceutical care services

11.1. Guiding principles of providing PC

During the outbreak of COVID-19, the goal of a community pharmacist is to provide COVID-19 oriented pharmaceutical care. While giving pharmaceutical care, the focus of pharmacists shall be on reducing the patients’ visits to any health care facility to reduce the chances of transmission and infection. Furthermore, each community pharmacy plans the types of particular PC regarding the necessities of the surrounding communities.

11.2. Approaches to providing PC

This At this worsen time of pandemic, a community pharmacist can effectively provide consultation services through various aspects. Remote access to the pharmacist in which the patients can contact the pharmacist for consultation via phone, mobile applications, and the internet, respectively. And this approach is efficiently safe for both patient and pharmacist. For example, in China, pharmacists and physicians use mobile applications to provide consultation to the patients. People can be informed such a service by displaying flyers in pharmacies and public places, through text messages, or emails. respectively. Furthermore, these means of communication can also be used in the scientific prevention and control of this pandemic. In addition, home delivery services of medicine can be employed to decrease the visits of patients to community pharmacies.

11.3. Pharmacist services during the COVID-19 pandemic

A community pharmacist can play the following roles in the pandemic:

11.3.1. Drug dispensing, patient screening, and referrals

Pharmacists at the time of dispensing must pay attention and ready to guide the hazardous effects of respiratory hygiene. In case of unavailability of medicine, he may encourage the patient to take therapeutic equivalent to prevent the patient’s travel to another pharmacy. Besides this, pharmacies should have a lesion with nearby healthcare and COVID-19 facility. At a community pharmacy, the pharmacist can monitor the temperature of the patients and take an interview to rule out the suspicion of COVID-19. In case any suspect or symptom observed, immediate isolation of such a patient must be performed, and pharmacists can help the patient in taking the immediate treatment in the designated health care facility for the COVID-19 patient. When the infected patients are recovered, then they are advised to go to quarantine at their homes because their immunity is compromised (房晓伟 et al., 2020). In quarantine period, pharmacists can also provide consultation and guidance services to the patients. See the CDC website for the criteria upon which the suspects are assessed. FIP interim guidelines guide isolation (Zheng et al., 2020).

11.3.2. Chronic disease management

During this pandemic, pharmacists may provide services to chronic patients. They can encourage the patients to adhere to their medication. Furthermore, he can guide and support them in self-monitoring to monitor the effectiveness of their therapy. They can teach them to buy their medication on time and make sure to have enough stock to avoid frequent visits to hospitals. They can also advise the patient not to stock the drugs with short-expiry at home. They can inform the patients about the availably of the drugs and the drug delivery services of the pharmacy, and they can encourage the patients to use such services. Furthermore, they can inform the patient’s chronic disease about the safety measure by which they self-monitor the outcomes of their therapy at their living abodes. For instance, if a patient suffering from hypertension after measuring 1–2 times per week, an increase in systolic pressure to 180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure to 110 mmHg, then he must advise to taking an immediate medical assessment.

The pharmacist can educate the patients about the adverse reactions they might experience while taking specific medicines. Also, he can guide them about the adverse reactions which they mainly have to monitor at home for a long period to stay in this pandemic. Further, he can also guide the patients on how they can distinguish between minor and adverse side effects. Additional guidance can be provided for the patients who are suffering from malignancies, irritable bowel syndrome, etc., or the patients who are taking drugs with a low margin of safety such as Warfarin. Patients might be unable to monitor INR, and further, it is quite possible that due to this pandemic, their diet is affected. Pharmacists can educate such patients regarding the monitoring of their signs and symptoms of bleeding. Furthermore, the source such patients via mobile applications is easily accessible way providing consultation and assessments (Hangoma et al., 2020).

11.3.3. Patient education

During a pandemic, pharmacists can provide educational services to a community regarding the prevention, early detection, and suitable medication, respectively. The scientific way of prevention and control of COVID-19 can be taught to the community through any sources. Such education may include the careful use of safety tools such as masks and disinfection products, hand and respiratory hygiene, and self-care approaches to home and at workplaces (Xunwu et al., 1998; Organization, 2020b; Zheng et al., 2020).

Furthermore, education regarding the transmission means, the onset of symptoms, and early detection of the suspected outcomes can be provided to the community. The more the community awareness, the more it will take care of and eradicate this disease. Additionally, the people that have enough educated are easy to distinguish between flu, cold, and COVID-19 symptoms, respectively, when they have received their medical supports. Young adults who are suffering from upper respiratory symptoms such as sore throat, runny nose, and sneezing, have to be provided with home care with isolation and symptomatic treatment. In case, the patient is observed with serious COVID-19 symptoms, then immediate medical help must be followed (Xunwu et al., 1998). Pharmacists must inform the surrounding community that there is no specific medicine or any effective vaccine available against COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, in case a person develops the suspected COVID-19 related symptoms like high fever, dry cough, and myalgia, and fatigue, respectively then medical assistance must be done timely and regularly. The use of so-called ‘wonder drugs’ must be avoided. Before dispensing, an assessment of a patient’s medications must be done, so the chance of duplication is prevented.

11.3.4. Homecare

Pharmacists can also advise the patients on the “Home care for patients with suspected novel coronavirus infection presenting with mild symptoms and management of contacts (Interim guidance)” published by WHO. In this manual, guidance regarding medical observation and treatment is given. The home at which the care is provided to the suspected patients is thoroughly cleaned, and proper hygiene guidelines regarding the care of such home isolated patients are followed (Zheng et al., 2020). Furthermore, it’s the responsibility of the pharmacist to make sure that all the family members of suspected patients are well-aware of the importance of scientific prevention and care, and they to have an idea about these skills.

12. Treatment of COVID-19 (unapproved therapy)

12.1. Current therapies

Until now, there is no specific medication for antiviral treatment COVID-19 patients. So currently, only symptomatic and supportive treatment is provided to patients (Gao et al., 2020). Almost all the patients require oxygen therapy, and WHO has recommended extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for patients who have refractory hypoxemia (Xie et al., 2020). To rescue critically ill patients, sometimes convalescent plasma and IgG are being used (Chen et al., 2020a).

12.2. Antiviral treatments

There are some strategies of treatment that we have learned from SARS and MERS outbreaks (Zumla et al., 2016). Antiviral drugs such as zanamivir, oseltamivir, peramivir, acyclovir, ganciclovir, and ribavirin, etc., and corticosteroids like methylprednisolone that are used for influenza virus are showed ineffective against COVID-19 (Li et al., 2020a).

In USA, Remdesivir has been successfully used against COVID-19 patients (Guan et al., 2020a). In a broad-spectrum antiviral prodrug and 1′-cyano-substituted adenosine nucleotide analog have been used. It is significantly effective against several RNA viruses. It interferes with NSP12 polymerase (Agostini et al., 2018).

Chloroquine is an anti-malarial drug, and it has been repurposed for COVID-19 (Aguiar et al., 2018). The proposed mechanism and actions of chloroquine in COVID-19 areas doesn’t let the many viruses to decrease their pH of the cell for replication (Savarino et al., 2003). SARS is most sensitive (Vincent et al., 2005); it has effective immunomodulatory effects that decreases the production of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, it also acts as an autophagy inhibitor (Golden et al., 2015), and interferes with the glycosylation of the receptors which viruses use to enter the cell (Vincent et al., 2005), hence it performs functions before and after the entry stages of the virus into the cell (Wang et al.).

Remdesivir and chloroquine, when used concomitantly, have shown efficacy against COVID-19 infection. Ritonavir and lopinavir, combinedly called Kaletra, is anti-HIV drugs (Cvetkovic and Goa, 2003), and they have shown promising results in SARS (Chu et al., 2004) and MERS infections (Arabi et al., 2018). In Korean COVID-19 patients, it has also shown some efficacy (Lim et al., 2020). Significant improvement has been seen in Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, China when Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir), arbidol, and a Chinese traditional medicine Shufeng Jiedu concomitantly were used for COVID-19 patients (Wang et al., 2020f). Thus, different candidates of potent antiviral drugs are summarized in (Table .2 ).

Table 2.

Common and potent antiviral drugs.

| Drug Status MOA Anti-infective mechanism Disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favipiravir | Investigational | Nucleoside analog viral RNA polymerase inhibitor | Acting on viral genetic copying to prevent its reproduction, without affecting host cellular RNA or DNA synthesis | Ebola, influenza A(H1N1) |

| Nitazoxanide | Approved/investigational, vet-approved | Antiprotozoal agent | Modulating the survival, growth, and proliferation of a range of extracellular and intracellular protozoa, helminths, anaerobic and microaerophilic bacteria, viruses | A wide range of viruses including human/animal coronaviruses |

| Ganciclovir | Approved/investigational | Nucleoside analog | Potent inhibitor of the Herpesvirus family including cytomegalovirus | AIDS-associated cytomegalovirus |

|

Penciclovir /acyclovir |

approved | nucleoside analog | A synthetic acyclic guanine derivative, resulting in chain termination | HSV, VZV |

| Oseltamivir | approved | Neuraminidase inhibitor | Inhibiting the activity of the viral neuraminidase enzyme, preventing the budding from the host cell, viral replication, and infectivity | Influenza viruses A |

| Ribavirin | approved | Synthetic guanosine nucleoside | Interfering with the synthesis of viral mRNA (a broad-spectrum activity against several DNA and RNA viruses) | HCV, SARS, MERS |

| Nafamostat | investigational | Synthetic serine protease inhibitor | Prevents membrane fusion by reducing the release of cathepsin B; anticoagulant activities | influenza, MERS, Ebola |

| Ramdesivir | experimental | Nucleotide analog prodrug | Interfering with virus post entry | Ebola, SARS, MERS, (A wide range of RNA viruses) |

| Chloroquine | Approved, investigational, vet approved | 9-aminoquinolin | Increasing endosomal pH, immunomodulating, autophagy inhibitors | Malaria, autoimmune disease |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | approved | Protease inhibitor | Inhibiting HM-1 protease for protein cleavage, resulting in non-infectious, immature viral particles | HIV/AIDS, SARS, MERS |

12.3. Adjunctive/supportive therapy

12.3.1. Azithromycin

Azithromycin belongs to macrolide antibiotics and it can also be used in COVID-19 infection as a supportive therapy against opportunistic bacterial infections. Additionally, it also has some immunomodulatory properties (Amsden, 2005; Beigelman et al., 2010; Kanoh and Rubin, 2010; Zarogoulidis et al., 2012; Gautret et al., 2020) it causes downregulation of the inflammatory response by decreasing the production of cytokines such as interleukin 8, etc. which are produced in response to the viruses. Furthermore, immunomodulatory responses include inhibition of excessive mucus secretion, reducing the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), stoppage of activation of nuclear transcription factors, and enhancing the apoptosis of neutrophils, respectively (Amsden, 2005; Beigelman et al., 2010; Kanoh and Rubin, 2010; Zarogoulidis et al., 2012).

In an open-label clinical and non-randomized trial, hydroxy-chloroquine and azithromycin were given combinedly to 26 patients. The purpose was to prevent patients from superinfections. The positive results showed the efficacy of the combination therapy. On day 6 of the treatment, all patients were cured this disease. On the other hand, when hydroxychloroquine was used alone the cure rate was reached up to 57% (Gautret et al., 2020).

According to a retrospective study, macrolides didn’t reduce the mortality as compared to the control group (adjusted OR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.47 to 1.51; p = 0.56). Also, their sensitivity was similar to that of control. (adjusted OR: 0.7; 95%CI: 0.39 to 1.28; p = 0.25) (Arabi et al., 2019). The main and alarming risk factor is arrhythmias because macrolide causes prolongation of QT-interval. Furthermore, their chances of drug-drug interactions are more powerful (Huber et al., 2019; Meds, 2020).

12.3.2. Tocilizumab

It is a monoclonal antibody, that inhibits the interleukin-6 receptor. Interleukin-6 is one of the main cytokines factor responsible for the inflammatory process. This is the rationale behind the use of this drug in COVID-19 treatment (Xu et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020a). IL-6 is produced by various types of cells-like B and T-cells, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and monocytes. There are various aspects in which IL-6 plays an active role in the body like it is involved in T-cell activation. It also causes induction of immunoglobulin induction, initiation of acute-phase protein synthesis in the liver. Furthermore, it is also involved in the stimulation of proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic precursor cells (Emery et al., 2019).

In a retrospective study of 21 COVID-19 patients, tocilizumab was given as an adjunct medicine. Results suggested the beneficial effects of tocilizumab. The percentage symptoms, of lymphocytes, level of C-reactive proteins and computerized tomography opacity changes were improved in the patients according to the observed study (Arabi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020a) hence some kinds of protocols for the treatment of COVID-19 recommend the use of tocilizumab (Lombardy, 2020), while to satisfy the concerns regarding the clinical efficacy, further studies are being carried to evaluate it (Phua et al., 2020). The safety risks concern gastrointestinal perforation, hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenic and neutropenic patients, as well as infusion-related reactions, respectively (Emery et al., 2019).

12.3.3. Leronlimab

It is an investigational drug. It is a humanized monoclonal antibody. It is for chemokine receptor CCR (Smith et al., 2020). It aids immune response by weakening the intensity of cytokine storm, the main reason for fatality in COVID-19 patients (Zhou et al., 2020a). After the approval of the Emergency Investigational New Drug Application (eIND) for COVID-19, the trials are being carried out on a small number of patients (Smith et al., 2020).

12.3.4. Sarilumab

It’s a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the activity of the interleukin-6 receptor. The rationale use in COVID-19 patients is its ability to mitigate the cytokine storm (Zhou et al., 2020a). There are two types of interleukin-6 receptors namely membrane-bound soluble, and Sarilumab, respectively that mainly bind with these receptors. Interleukin-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine; it is released from a variety of immune cells like fibroblasts, lymphocytes, B and T-cells, and monocytes, respectively. It also performs various physiological functions which are discussed under the heading of Tocilizumab (Banker et al., 2018; Alvi et al., 2020). Clinical data regarding its efficacy is being investigated (Alvi et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020).

12.3.5. Anti-bodies and plasma therapy

The recovered COVID-19 patients have the antibodies in their plasma (convalescent plasmas) to fight against the virus. Clinical trials are being conducted to check the effectiveness of such antibodies. These cannot be used for the prevention of viral infection (Food et al., 2017).

Evidence/Experience.

Five critically ill patients who were also suffering from ARDS received convalescent plasma (Shen et al., 2020). On the same day obtained COVID-19 specific antibodies IgG (titer > 1:1000) in convalescent plasma was given in 2 consecutive transfusions comprising a total of 400 mL. For the initiation of clinical trials, the researchers are an urge on an investigation of a new drug or IND application to the FDA. On the other hand, the physicians can submit an emergency on IND application to obtain convalescent plasma from a single patient.

The patients who meet the following criteria are included in trials:

-

•

Patients suffering from severe pneumonia and having high viral load (PAO2/FIO2 less than 300) despite the antiviral treatment

-

•

They were on mechanical ventilation

-

•

After the inoculation of convalescent plasma, their fever becomes normal within 3 days; sequential organ failure assesses (SOFA) decreased and PAO2/FIO2 was increased within 12 days.

-

•

Within 12 days after transfusion of COVID-19 specific antibodies, viral load first decreased and then became negative. Furthermore, the antibody tire increased after transfusion.

-

•

After the transfusion, four patients were fully recovered from ARDS within 12 days, and three patients were removed from ventilators within two weeks of treatment.

The following is the criteria to obtain authorization for use of convalescent plasma:

•For an emergency condition such as when the response is required in less than 4 h, the application form 3926 is used. And meanwhile, verbal authorization can be taken by contacting the Office of Emergency Operations of FDA at 1-866-300-4374. After the verbal authorization, the requestor must submit form to 3926 within 15 working days

•For situations which are not highly sensitive and response for them is required within 4–8 h, the requestor completes the form and submits it to FDA through email address: CBER_eIND_Covid-19@FDA.HHS.gov. The form shall include the clinical history of the patient which includes the complete diagnosis, therapy given by the time being, and justification of the request of use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Further, it will also include the information of the person from convalescent plasma will be obtained. After review, the FDA either accepts or rejects the request. In case of authorization, FDA will email the requestor about the approval of the application and provide him eIND number.

Collection of COVID-19 convalescent plasma.

From the fully recovered patients, plasma can be obtained. Before collection, proper testing must be performed. Moreover, the following criteria for the donor person must be checked:

-

•

Diagnostic and recovery record of COVID-19 disease

-

•

Male and female donors negative for HLA antibodies

-

•

Before donation, at least 14 days have been passed after the complete resolution of the symptoms

Negative results for COVID-19 either from:

COVID-19 negative results can be obtained either from:

•1 or more nasopharyngeal swab specimens

•The molecular diagnostic test of their blood

•COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies’ titer must be greater than 1:320

•The collecting container must include the statement, “Caution: New Drug—Limited by Federal (or the United States) law to investigational use.” (Shen et al., 2020)

12.3.6. Corticosteroids

They are not recommended in COVID-19 patients unless and until they are suffering from ARDS or refractory shock (Jin et al., 2020a; Lian et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Wu et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020b).

12.3.7. Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators

Aerosolized vasodilators such as nitric oxide, prostacyclin, etc. are not advised. Furthermore, there is no evidence of their use in ARDS for COVID-19 patients (Matos and Chung, 2020; Smith et al., 2020).

•In case when the patient develops refractory hypoxemia despite the use of other strategies of optimization, then as a delaying measure the use of inhaled vasodilators may be commissioned (Matos and Chung, 2020; Smith et al., 2020).

•A short trial before the use of Nitric oxide is recommended (Smith et al., 2020)

•Further studies are being carried out to evaluate their efficacy in COVID-19 patients (Maron et al., 2020).

12.3.8. NSAIDs

The investigation regarding the use of NSAIDs in COVID-19 patients is being carried out by the FDA. Useful concern for potential worsening of COVID-19 symptoms has been suggested, but confirmatory clinical data is lacking at this time (Loutfy et al., 2003). In a letter, it has been suggested that the use of Ibuprofen may enhance the number of ACE2 receptors at which the coronavirus bind (Fang et al., 2020) However, for temperature control, Acetaminophen can be used (Smith et al., 2020). Furthermore, it can also be used in critically ill hyper-thermic patients with COVID-19 infection (Smith et al., 2020).

12.3.9. Bronchodilators

There is no role of inhalational bronchodilators in COVID-19 patients. But when the COVID-19 patient is already suffering from asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) then they are recommended to the patients (Bablani et al., 2020). Furthermore, metered-dose inhalers (MDI) are preferred over nebulizers because the latter may enhance the risk of viral transmission in the process of aerosolization (Bablani et al., 2020). To tackle the shortage of supply of MDI, manufacturers are focusing on the development of a protocol to recommend the same MDI for more patients. The protocol should focus on hand sanitization and dual canister disinfection to eradicating the transmission of virus (Bablani et al., 2020).

13. Conclusions, future trends and perspectives

The COVID-19 pandemic is an impending threat around the globe that not only imposed serious physical, illness, and death but also showed severe complications on the mental activities of the peoples. Medical and health workers are treating patients with a frequent and high dose of potentially available broad-spectrum antibodies and antiviral drugs include: lopinavir/ritonavir, chloroquine, remdesivir for the quickly recovered and cure the infected COVID-19 patients, but most of these drugs showed a harmful effect and cause severe complications such as kidney dysfunction, mental health, and respiratory problems, respectively. Many pharmaceutical companies are currently urged to develop active and efficient vaccines against different strains of this virus to eradicate this disease from this entire world. The future research direction can deliver a better perception against this infection. Additionally, further work will be explored to a comparative study by collecting the quantitative data from the first and second wave for COVID-19 and their statistical analysis on different phases to determine the spreading and transmission of disease dynamics across the world shortly in the future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the Kohat University of Science and Technology (KUST).

Handling Editor: Jianying Hu

References

- Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X., Smith E.C., Case J.B., Feng J.Y., Jordan R. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar A.C., Murce E., Cortopassi W.A., Pimentel A.S., Almeida M.M., Barros D.C., Guedes J.S., Meneghetti M.R., Krettli A.U. Chloroquine analogs as antimalarial candidates with potent in vitro and in vivo activity. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs and Drug Resistance. 2018;8:459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvi M.M., Sivasankaran S., Singh M. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological efforts at prevention, mitigation, and treatment for COVID-19. J. Drug Target. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2020.1793990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsden G. Anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides—an underappreciated benefit in the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infections and chronic inflammatory pulmonary conditions? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;55:10–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y.M., Alothman A., Balkhy H.H., Al-Dawood A., AlJohani S., Al Harbi S., Kojan S., Al Jeraisy M., Deeb A.M., Assiri A.M. Treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-β1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y.M., Deeb A.M., Al-Hameed F., Mandourah Y., Almekhlafi G.A., Sindi A.A., Al-Omari A., Shalhoub S., Mady A., Alraddadi B. Macrolides in critically ill patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;81:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argulian E. American College of Cardiology Foundation; Washington DC: 2020. Anticipating the “Second Wave” of Health Care Strain in the COVID-19 Pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H., Al-Nassir W.N., Balkhy H.H., Al-Hakeem R. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bablani P., Shamsi Y., Kapoor P., Sharma M., Arora S. COVID-19 & Effectiveness towards it’s available treatment. IJRAR-International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews (IJRAR) 2020;7:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Banker A.S., Pavesio C., Merrill P. Emerging treatments for non-infectious uveitis. Journal-Emerging Treatments for Non-infectious Uveitis. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M., Vena A., Giacobbe D. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections. Challenges for fighting the storm. 2020;50 doi: 10.1111/eci.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigelman A., Mikols C.L., Gunsten S.P., Cannon C.L., Brody S.L., Walter M.J. Azithromycin attenuates airway inflammation in a mouse model of viral bronchiolitis. Respir. Res. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belouzard S., Chu V.C., Whittaker G. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. 2009;106:5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoch I.I., Watts A., Thomas-Bachli A., Huber C., Kraemer M.U., Khan K. vol. 27. 2020. (Pneumonia of Unknown Aetiology in Wuhan, China: Potential for International Spread via Commercial Air Travel). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R.M.J.M.M., report m.w. 2020. Active Monitoring of Persons Exposed to Patients with Confirmed COVID-19—United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapaglia G., Cot C., Sannino F.J.S.r. Second wave COVID-19 pandemics in Europe: a temporal playbook. 2020;10:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72611-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M.J., Bermejo-Martin J.F., Danesh A., Muller M.P., Kelvin D.J.J.V.r. Human immunopathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) 2008;133:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos W.G., Dela Cruz C.S., Cao B., Pasnick S., Jamil S., Medicine C.C. vol. 201. 2020. pp. P7–P8. (COVID-19 Disease Due to SARS-CoV-2 (Novel Coronavirus)). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., Dulebohn S.C., Di Napoli R. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.-W., Kok K.-H., Zhu Z., Chu H., To K.K.-W., Yuan S., Yuen K.-Y.J.E.m., infections Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. 2020;9:221–236. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.-W., To K.K.-W., Tse H., Jin D.-Y., Yuen K. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: lessons from bats and birds. 2013;21:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.-W., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.-Y., Poon R. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R., Fehr A.R., Vijay R., Mack M., Zhao J., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S.J.C.h., microbe Dysregulated type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS-CoV-infected mice. 2016;19:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R., Fehr A.R., Zheng J., Wohlford-Lenane C., Abrahante J.E., Mack M., Sompallae R., McCray P.B., Meyerholz D.K., Perlman S. vol. 129. 2019. (IFN-I Response Timing Relative to Virus Replication Determines MERS Coronavirus Infection Outcomes). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Seminars in Immunopathology. Springer; 2017. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology; pp. 529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Xiong J., Bao L., Shi Y. Convalescent plasma as a potential therapy for COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:398–400. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-M.A., Liang S.-Y., Shih Y.-P., Chen C.-Y., Lee Y.-M., Chang L., Jung S.-Y., Ho M.-S., Liang K.-Y., Chen H. Epidemiological and genetic correlates of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the hospital with the highest nosocomial infection rate in Taiwan. 2006;44:359–365. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.359-365.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C., Cheng V., Hung I., Wong M., Chan K., Chan K., Kao R., Poon L., Wong C., Guan Y. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovic R.S., Goa K.L. Lopinavir/ritonavir. Drugs. 2003;63:769–802. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit E., Van Doremalen N., Falzarano D., Munster V. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. 2016;14:523. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit A.J.N.R.M. vol. 18. 2020. (Outbreak of a Novel Coronavirus). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery P., Rondon J., Parrino J., Lin Y., Pena-Rossi C., van Hoogstraten H., Graham N.M., Liu N., Paccaly A., Wu R. Safety and tolerability of subcutaneous sarilumab and intravenous tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2019;58:849–858. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y.-Y., Huang Z.-T., Li L., Wu M.-H., Yu T., Koup R.A., Bailer R.T., Wu C. Characterization of SARS-CoV-specific memory T cells from recovered individuals 4 years after infection. 2009;154:1093–1099. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L., Karakiulakis G., Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? The Lancet. Respir. Med. 2020;8:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food U., Food D.A.J.U., June D. vol. 28. CBER); 2017. (Investigational New Drug (IND) or Device Exemption (IDE) Process). [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Bioscience trends. 2020 doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P., Lagier J.-C., Parola P., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Courjon J., Giordanengo V., Vieira V.E., Dupont H.T. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Golden E.B., Cho H.-Y., Hofman F.M., Louie S.G., Schönthal A.H., Chen T.C. Quinoline-based antimalarial drugs: a novel class of autophagy inhibitors. Neurosurg. Focus. 2015;38:E12. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.FOCUS14748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., Liang W.-h., Ou C.-q., He J.-x., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-l., Hui D.S. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., Liang W.-h., Ou C.-q., He J.-x., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-l., Hui D. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajeer A.H., Balkhy H., Johani S., Yousef M.Z., Arabi Y. Association of human leukocyte antigen class II alleles with severe Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus infection. 2016;11:211. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.185756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M., Lely A., Navis G.v., van Goor H., Ireland . vol. 203. 2004. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus; pp. 631–637. (A First Step in Understanding SARS Pathogenesis). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hâncean M.-G., Perc M., Lerner J. Early spread of COVID-19 in Romania: imported cases from Italy and human-to-human transmission networks. 2020;7:200780. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangoma J.M., Mudenda S., Mwenechanya M.M., Kalungia A.C. medRxiv; 2020. Community Pharmacists’ Knowledge and Preparedness to Participate in the Fight against Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zambia. [Google Scholar]

- Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A. 2020. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X.J.T.l. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Xia J., Chen Y., Shan C., Wu C. A family cluster of SARS-CoV-2 infection involving 11 patients in Nanjing, China. 2020;20:534–535. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30147-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber P., Flynn A., Sultan M.B., Li H., Rill D., Ebede B., Gundapaneni B., Schwartz J.H. A comprehensive safety profile of tafamidis in patients with transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathy. Amyloid. 2019;26:203–209. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2019.1643714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers S.A., Tusell S.M., Gillim-Ross L., Hemmila E.M., Achenbach J.E., Babcock G.J., Thomas W.D., Thackray L.B., Young M.D., Mason R. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. 2004;101:15748–15753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403812101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.-H., Cai L., Cheng Z.-S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y.-P., Fang C., Huang D., Huang L.-Q., Huang Q. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Military Medical Research. 2020;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.-H., Cai L., Cheng Z.-S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y.-P., Fang C., Huang D., Huang L.-Q., Huang Q.J.M.M.R. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) 2020;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh S., Rubin B.K. Mechanisms of action and clinical application of macrolides as immunomodulatory medications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:590–615. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00078-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keicho N., Itoyama S., Kashiwase K., Phi N.C., Long H.T., Van Ban V., Hoa B.K., Le Hang N.T., Hijikata M., Sakurada S.J.H.i. Association of human leukocyte antigen class II alleles with severe acute respiratory syndrome in the Vietnamese population. 2009;70:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball A., Hatfield K.M., Arons M., James A., Taylor J., Spicer K., Bardossy A.C., Oakley L.P., Tanwar S., Chisty Z.J.M., Report M.W. vol. 69. 2020. Asymptomatic and Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Residents of a Long-Term Care Skilled Nursing Facility—King County; p. 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba K., Imai Y., Ohto-Nakanishi T., Penninger J.M.J.P., therapeutics Trilogy of ACE2: a peptidase in the renin–angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters. 2010;128:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., Azman A.S., Reich N.G., Lessler J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N., Hui D., Wu A., Chan P., Cameron P., Joynt G.M., Ahuja A., Yung M.Y., Leung C., To K. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.-I., Hsueh P., Immunology Infection. 2020. Emerging Threats from Zoonotic Coronaviruses-From SARS and MERS to 2019-nCoV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J., Li J., Li X., Qi X.J.R. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. 2020;295 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Chen X., Xu A. Profile of specific antibodies to the SARS-associated coronavirus. 2003;349:508–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200307313490520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wang Y., Xu J., Cao B. Potential antiviral therapeutics for 2019 Novel Coronavirus. Zhonghua jie he he hu xi za zhi= Zhonghua jiehe he huxi zazhi= Chinese. journal of tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2020;43 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S., Lau E.H., Wong J. 2020. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C.J.N. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J., Jin X., Hao S., Cai H., Zhang S., Zheng L., Jia H., Hu J., Gao J., Zhang Y. Analysis of epidemiological and clinical features in older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outside Wuhan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:740–747. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J., Jeon S., Shin H.-Y., Kim M.J., Seong Y.M., Lee W.J., Choe K.-W., Kang Y.M., Lee B., Park S.-J. Case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of COVID-19 infection in Korea: the application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 infected pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 2020;35 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling A., Leo Y.J.E.I.D. Potential presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Zhejiang province, China. 2020;26:1052–1054. doi: 10.3201/eid2605.200198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Liao X., Qian S., Yuan J., Wang F., Liu Y., Wang Z., Wang F.-S., Liu L., Zhang Z. Shenzhen; China: 2020. Community Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yan L.-M., Wan L., Xiang T.-X., Le A., Liu J.-M., Peiris M., Poon L.L., Zhang W. 2020. Viral Dynamics in Mild and Severe Cases of COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardy S.I.S.I. vol. 28. 2020. Vademecum for the treatment of people with COVID-2.0, 13 March 2020; p. 143. (Le Infezioni in Medicina). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutfy M.R., Blatt L.M., Siminovitch K.A., Ward S., Wolff B., Lho H., Pham D.H., Deif H., LaMere E.A., Chang M. Interferon alfacon-1 plus corticosteroids in severe acute respiratory syndrome: a preliminary study. Jama. 2003;290:3222–3228. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.24.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. 2020;92:401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.J.B.t. Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 2020;14:69–71. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron B.A., Gladwin M.T., Bonnet S., De Jesus Perez V., Perman S.M., Yu P.B., Ichinose F. Perspectives on cardiopulmonary critical care for patients with COVID-19: from members of the American heart association council on cardiopulmonary, critical care, perioperative and resuscitation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos R.I., Chung K.K. Defense Health Agency Falls Church United States; 2020. DoD COVID-19 Practice Management Guide: Clinical Management of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Meds C. 2020. COVID-19 Experimental Therapies and TdP Risk. [Google Scholar]

- Menachery V.D., Schäfer A., Burnum-Johnson K.E., Mitchell H.D., Eisfeld A.J., Walters K.B., Nicora C.D., Purvine S.O., Casey C.P., Monroe M. vol. 115. 2018. pp. E1012–E1021. (MERS-CoV and H5N1 Influenza Virus Antagonize Antigen Presentation by Altering the Epigenetic Landscape). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet J.K., Whittaker G. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. 2014;111:15214–15219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407087111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C.-K., Cheon S., Ha N.-Y., Sohn K.M., Kim Y., Aigerim A., Shin H.M., Choi J.-Y., Inn K.-S., Kim J.-H.J.S.r. Comparative and kinetic analysis of viral shedding and immunological responses in MERS patients representing a broad spectrum of disease severity. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep25359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiura H., Jung S.-m., Linton N.M., Kinoshita R., Yang Y., Hayashi K., Kobayashi T., Yuan B., Akhmetzhanov A.R. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020. The Extent of Transmission of Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]