Abstract

Background

During the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, risks associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in pregnancy were uncertain. Pregnant patients can serve as a model for the success of clinical and public health responses during public health emergencies as they are typically in frequent contact with the medical system. Population-based estimates of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections in pregnancy are unknown because of incomplete ascertainment of pregnancy status or inclusion of only single centers or hospitalized cases. Whether pregnant women were protected by the public health response or through their interactions with obstetrical providers in the early months of pandemic is not clearly understood.

Objective

This study aimed to estimate the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy and to examine the disparities by race and ethnicity and English language proficiency in Washington State.

Study Design

Pregnant patients with a polymerase chain reaction–confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection diagnosed between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2020 were identified within 35 hospitals and clinics, capturing 61% of annual deliveries in Washington State. Infection rates in pregnancy were estimated overall and by Washington State Accountable Community of Health region and cross-sectionally compared with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rates in similarly aged adults in Washington State. Race and ethnicity and language used for medical care of pregnant patients were compared with recent data from Washington State.

Results

A total of 240 pregnant patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections were identified during the study period with 70.7% from minority racial and ethnic groups. The principal findings in our study were as follows: (1) the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate was 13.9 per 1000 deliveries in pregnant patients (95% confidence interval, 8.3–23.2) compared with 7.3 per 1000 (95% confidence interval, 7.2–7.4) in adults aged 20 to 39 years in Washington State (rate ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.3–2.3); (2) the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate reduced to 11.3 per 1000 deliveries (95% confidence interval, 6.3–20.3) when excluding 45 cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease 2 detected through asymptomatic screening (rate ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 0.96–1.9); (3) the proportion of pregnant patients in non-White racial and ethnic groups with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease 2 infection was 2- to 4-fold higher than the race and ethnicity distribution of women in Washington State who delivered live births in 2018; and (4) the proportion of pregnant patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection receiving medical care in a non-English language was higher than estimates of pregnant patients receiving care with limited English proficiency in Washington State (30.4% vs 7.6%).

Conclusion

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnant people was 70% higher than similarly aged adults in Washington State, which could not be completely explained by universal screening at delivery. Pregnant patients from nearly all racial and ethnic minority groups and patients receiving medical care in a non-English language were overrepresented. Pregnant women were not protected from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in the early months of the pandemic. Moreover, the greatest burden of infections occurred in nearly all racial and ethnic minority groups. These data coupled with a broader recognition that pregnancy is a risk factor for severe illness and maternal mortality strongly suggested that pregnant people should be broadly prioritized for coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine allocation in the United States similar to some states.

Key words: Alaskan Native, American Indian, Black, coronavirus, coronavirus disease 2019, ethnic disparity, fetus, Hispanic, infection rate, Pacific Islander, pregnancy, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Washington State

Introduction

In the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, risks associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in pregnancy were uncertain.1 As pregnant patients are typically in frequent contact with the medical system, they can serve as a model for the success of the clinical and public health responses during public health emergencies. Outside US urban centers with high infection rates, studies in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic reported low SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in pregnant patients undergoing universal screening at admission to the hospital for delivery.2, 3, 4 Population-based estimates of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy are lacking because of incomplete ascertainment of pregnancy status or inclusion of only single centers or hospitalized cases.10, 11, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Furthermore, a disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities, including pregnant patients, has been reported.5 , 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 However, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data are missing pregnancy status for 65% of their COVID-19 case report forms, making it impossible to estimate infection rates in the US pregnant population.16 Population-based studies of COVID-19 in pregnancy with comprehensive data regarding race, ethnicity, and language are essential to developing effective interventions for populations disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

To determine the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection rate in pregnant patients and to assess racial and ethnic disparities in a multicenter, retrospective cohort study in Washington State.

Key findings

The SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was significantly higher in pregnant people (N=240; 13.9 per 1000 deliveries) than people aged 20 to 39 years (7.3 per 1000; rate ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.3–2.3) in Washington State. Compared with the distribution of women in Washington State who delivered live births in 2018, the proportion of pregnant women from racial and ethnic minority groups with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 2- to 4-fold higher.

What does this add to what is known?

The SARS-CoV-2 infection rate in pregnant patients was higher than nonpregnant adults in Washington State, and nearly all non-White racial and ethnic groups were disproportionately affected.

Washington State provided a valuable case study evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant individuals. In addition, Washington State was the first state to detect community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and imposed a shelter-in-place order.17 Here, we aimed to estimate and compare the infection rates between pregnant patients and similarly aged adults in Washington State and to examine the disparities by race and ethnicity and language use.

Materials and Methods

Study population

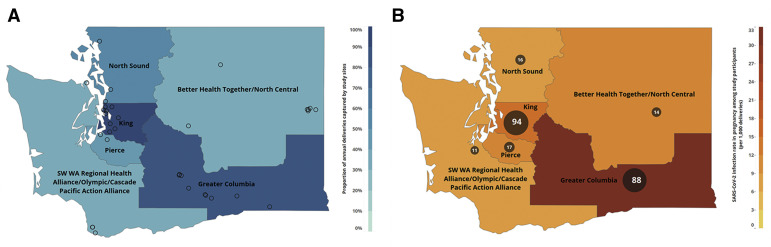

The Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative (WA-CPC) identified pregnant women (≥18 years) with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed using a polymerase chain reaction test from 35 hospitals and clinics in Washington State between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2020 (Figure ; Supplemental Table 1). Each site identified patients with an infection during any trimester of pregnancy irrespective of pregnancy outcome, abstracted clinical and SARS-CoV-2 testing data from medical records, and reported number of annual deliveries, actual number of deliveries during the study period, and SARS-CoV-2 testing strategies employed over time.19 Pregnant women were tested for several reasons during the study period, including exposure to a known SARS-CoV-2 case, universal screening before procedures or delivery, symptoms, travel, and personal requests. Testing occurred in the general population for similar reasons, including universal testing before medical procedures, with increasing test availability over time. Race and ethnicity data abstracted from medical records were self-reported by patients.

Figure.

Number of study sites, proportion of deliveries, and number of COVID-19 cases

A, The number of study sites (circles) and proportion of deliveries (color gradient) captured by the Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative is depicted within each Washington State Department of Health ACH region. B, The number of COVID-19 cases in pregnant patients within each ACH region is shown numerically and by circle size with infection rate in pregnancy depicted by the color gradient.

ACH, Accountable Community of Health; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

This multisite medical record review was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of Washington (study number 00009701, approved March 6, 2020) and Swedish Medical Center (study number 2020000172, approved March 19, 2020). All other sites entered into reliance agreements with the University of Washington IRB. The IRB waived the need for informed consent. Data provided by each site were deidentified.

Statistical analysis

To estimate statewide coverage of annual deliveries captured at WA-CPC sites and the SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in pregnancy, we assessed site-specific data (SARS-CoV-2 cases, number of deliveries) within the Washington State Accountable Community of Health (ACH) regions.18 , 20 Because of small case numbers in some of the 9 ACH regions, we collapsed geographically close regions to yield 6 regions for analysis (Figure). To estimate the proportion of annual statewide deliveries captured by collaborating sites, the number of total site-reported annual deliveries was divided by the number of live births in 2018 in Washington State and by ACH region using Washington State Department of Health (WA-DOH) data.18

The ACH-specific and overall SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in pregnancy (per 1000 deliveries) at WA-CPC sites were estimated using the site-specific infection rate (number of cases divided by number of deliveries during the study period) and Poisson regression (with 95% confidence interval [CI]), with clustering by ACH region for the overall estimate. As a comparison group, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in all patients aged 20 to 39 years (females and males) in Washington State during the study period were calculated using publicly available SARS-CoV-2 surveillance data for confirmed cases (numerator) and 2019 population estimates for patients aged 20 to 39 years (denominator); we were unable to exclude cases in men because of limitations of the publicly available surveillance data.21 , 22 This group served as the best available proxy estimate for the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate for reproductive-aged women. Although women aged <20 and >39 years are fecund, Washington State SARS-CoV-2 surveillance data were only available in wide categories, including 0 to 19 years, 20 to 39 years, 40 to 59 years, and older categories; neither age groups of 0 to 19 years nor 40 to 59 years were appropriate comparison groups for approximating infection rates in most reproductive-age women, and therefore, the 20- to 39-year-old age group was selected for comparison. Rate ratios (RR) and 95% CI were calculated comparing WA-CPC infection rates in pregnancy with overall SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of patients aged 20 to 39 years in Washington State within each ACH region; an ACH-weighted overall RR was also estimated. To assess how infection rates in pregnancy may have been affected by increased access to testing in the pregnant population, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding cases of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy detected through asymptomatic universal screening before procedures or delivery. We were unable to subtract cases in the general population comparison group similarly identified through preprocedure universal testing. Lastly, the WA-DOH provided SARS-CoV-2 case counts of pregnant females aged 18 to 50 years between March 1, 2020, and June 30, 2020, by ACH region for comparison23; pregnancy status was ascertained through public health department investigation. As a sensitivity analysis, infection rates in pregnancy were calculated, and the DOH-reported case counts and the statewide live births were estimated from March 2020 to June 2020 using Washington State 2018 birth data.18

We compared the race and ethnicity distribution of the study population with that of women who delivered live births in 2018 in Washington State.18 Race and ethnicity data were categorized as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, multiracial, and White; Hispanic was considered a mutually exclusive race and ethnicity group to align with WA-DOH categories.18 For each race and ethnicity category among pregnant patients in the study population, prevalence and exact 95% CI were estimated with clustering by ACH region. Furthermore, we generated ACH-weighted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CI comparing the race and ethnicity in the study population with the race and ethnicity distribution of women who delivered live births in 2018 in Washington State. In addition, we generated PRs for the King and Greater Columbia ACH regions, which had the highest number of SARS-CoV-2 cases through June 30, 2020.21 For ACH-specific analyses, race and ethnicity data were repressed when there were <10 cases in alignment with WA-DOH privacy guidelines. Moreover, we compared the proportion of pregnant patients in our study receiving medical care in a non-English language with the proportion of individuals receiving care in Washington State in 2017 with limited English language proficiency (individuals aged >5 years, who speak English “less than very well”) per 2014–2017 American Community Survey data reported by the WA-DOH.20 Each publicly available data source and how it contributed to these analyses are further described in Supplemental Table 2.

Results

Capture of pregnancies and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections among pregnant patients at Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative sites

The estimated proportion of annual deliveries in Washington State covered at WA-CPC sites was 61.1%, ranging from 35.0% to 93.0% by region (Figure; Table 1 ). Of 35 WA-CPC sites, 22 (62.9%) were hospitals and 13 were clinics providing prenatal care only. Patients were universally screened for SARS-CoV-2 infection using nasopharyngeal swab tests before or at the time of admission for delivery in 14%, 64%, and 76% of hospitals by the end of March, April, and May, respectively. The 5 hospitals without universal testing at delivery by the end of May had initiated universal testing for scheduled delivery admissions only.

Table 1.

WA-CPC statewide coverage of pregnancies and cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reported to the WA-DOH

| ACH region | WA-CPC |

SARS-CoV-2 cases in pregnancy |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites |

Annual deliveries at sitesa |

Live births in WA in 2018b |

Cases detected by WA-CPC |

Cases reported to the WA-DOHc |

|||||||

| n | n | (%) | n | (%) | Percentage captured by WA-CPC, % | n | (%) | n | (%) | Percentage captured by WA-CPC,d % | |

| Better Health Together or North Central | 7 | 3832 | (7.3) | 10,129 | (11.8) | 37.8 | 14 | (5.8) | 23 | (6.6) | 60.9 |

| Greater Columbia | 10 | 7720 | (14.7) | 9438 | (11.0) | 81.8 | 88 | (36.7) | 135 | (39.0) | 65.2 |

| King | 9 | 22,623 | (43.1) | 24,337 | (28.3) | 93.0 | 94 | (39.2) | 98 | (28.3) | 95.9 |

| North Sound | 3 | 7460 | (14.2) | 14,265 | (16.6) | 52.3 | 16 | (6.7) | 60 | (17.3) | 26.7 |

| Pierce | 2 | 5148 | (9.8) | 11,462 | (3.3) | 44.9 | 17 | (7.1) | 20 | (5.8) | 85.0 |

| SW Washington State Regional Health, Olympic, or Cascade Pacific Action Alliance | 4 | 5725 | (10.9) | 16,375 | (19.0) | 35.0 | 11 | (4.6) | 10 | (2.9) | 110.0 |

| Washington State total | 35 | 52,508 | (100) | 86,006e | (100) | 61.1 | 240 | 346 | 69.4 | ||

Adapted from Washington State Department of Health.18

ACH, Accountable Community of Health; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WA-CPC, Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative; WA-DOH, Washington State Department of Health.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Approximate annual deliveries were reported by each site

2018 data from the WA-DOH birth data dashboard tool (Birth Certificate Data, 2000–2018, Community Health Assessment Tool)

Case counts of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases among females aged 18 to 50 years who were pregnant at the time of infection were provided by the WA-DOH from March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Pregnancy status was ascertained through case interviews or by local health jurisdiction investigation. In 35% of SARS-CoV-2 case records among females aged 18 to 50 years, pregnancy status was unknown or missing

Direct linking of WA-CPC and WA-DOH cases was not possible, so the exact overlap of WA-CPC and WA-DOH identified cases is unknown

The total number of live births in Washington State in 2018 was 84,046, but 40 cases were not attributed to an ACH region.

A total of 240 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy were detected at WA-CPC sites.24 Most SARS-CoV-2 cases in pregnancy were detected in the King (94 [39.2%]) and Greater Columbia (88 [36.7%]) ACH regions (Figure; Table 1). Of the WA-CPC cases, 38 (15.8%) were detected in the first trimester of pregnancy, 67 (27.9%) in the second trimester of pregnancy, and 135 (56.3%) in the third trimester of pregnancy, as previously reported.24 Of the 240 cases, 45 (18.8%) were diagnosed through asymptomatic screening strategies (preprocedure and universal screening before delivery); this screening strategy excludes patients who were asymptomatic but were tested due to having a known exposure to COVID-19.

During the study period, the WA-DOH identified 346 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy throughout Washington State, but pregnancy status was missing for 35% of the cases in females aged 18 to 50 years.25 The WA-CPC captured 240 of 346 SARS-CoV-2 infections (69.4%) in pregnancy that were reported to the WA-DOH, ranging from 26.7% to 110.0% of cases at the ACH region level (Table 1). However, direct linking of the WA-CPC and WA-DOH cases was not possible, so the exact overlap of the WA-CPC– and WA-DOH–identified cases is unknown.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rates

The overall infection rate in pregnancy at WA-CPC sites was 13.9 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 8.3–23.2). At the ACH region level, infection rates in pregnancy at WA-CPC sites ranged from 6.2 per 1000 (95% CI, 3.2–11.2) to 33.2 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 26.9–40.9) (Figure; Table 2 ). In the King ACH region, where capture rates of annual deliveries and state reported SARS-CoV-2 cases in pregnancy were >90%, the infection rate in pregnancy at WA-CPC sites was 12.9 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 10.5–15.8). Compared with the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate among patients aged 20 to 39 years in Washington State of 7.3 per 1000 (95% CI, 7.2–7.4), the overall infection rate in pregnancy at WA-CPC sites was 1.7 times higher (ACH-weighted RR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3–2.3) (Table 2). The result equates to an absolute risk difference of 5.4 per 1000 (95% CI, 0.8–10.0). Moreover, there were significantly higher infection rates in pregnancy in some, but not all, ACH regions (Table 2). For example, in the King ACH region, there was a 2.2 times higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnant women at WA-CPC sites compared with individuals aged 20 to 39 years (RR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.8–2.8). In the sensitivity analysis estimating the infection rate in pregnancy using the WA-DOH–reported SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy case counts, the statewide infection rate in pregnancy was similar to that estimated using data from WA-CPC sites (WA-DOH, 12.1 per 1000 deliveries; 95% CI, 10.8–13.4) and was 1.7 times higher than that of individuals aged 20 to 39 years in Washington State (95% CI, 1.4–2.2) (Supplemental Table 3). Finally, when excluding the 45 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy that were detected through asymptomatic screening strategies (preprocedure and universal testing at delivery) at WA-CPC sites, the overall infection rate in pregnancy at WA-CPC sites was 11.3 per 1000 deliveries (95% CI, 6.3–20.3), which was 30% higher than the infection rate of individuals aged 20 to 39 years in Washington State (ACH-weighted RR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.96–1.9) (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rates in pregnancy in Washington State

| ACH region | Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative |

Washington State: 20–39 y |

RR |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases in pregnancy |

Deliveries during the study period |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 deliveries |

Casesa |

Populationb n |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 |

||||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | ||

| Better Health Together or North Central | 14 | (5.8) | 1318 | (7.6) | 10.6 | (6.3–17.9) | 1746 | (11.5) | 214,300 | 8.1 | (7.8–8.5) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.2) |

| Greater Columbia | 88 | (36.7) | 2653 | (15.4) | 33.2 | (26.9–40.9) | 5459 | (35.8) | 193,851 | 28.2 | (27.4–28.9) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.4) |

| King | 94 | (39.2) | 7283 | (42.3) | 12.9 | (10.5–15.8) | 4274 | (28.0) | 744,386 | 5.7 | (5.6–5.9) | 2.2 | (1.8–2.8) |

| North Sound | 16 | (6.7) | 2506 | (14.5) | 6.4 | (3.9–10.4) | 1752 | (11.5) | 325,671 | 5.4 | (5.1–5.6) | 1.2 | (0.7–1.9) |

| Pierce | 17 | (7.1) | 1696 | (9.8) | 10.0 | (6.2–16.1) | 1173 | (7.7) | 239,814 | 4.9 | (4.6–5.2) | 2.0 | (1.2–3.3) |

| SW Washington State Regional Health, Olympic, or Cascade Pacific Action Alliance | 11 | (4.6) | 1777 | (10.3) | 6.2 | (3.4–11.2) | 834 | (5.5) | 358,226 | 2.3 | (2.2–2.5) | 2.7 | (1.3–4.8) |

| Washington State total | 240 | 17,233 | 13.9 | (8.3–23.2)c | 15,238d | 2,076,248 | 7.3 | (7.2–7.4) | 1.7 | (1.3–2.3)e | |||

Adapted from the Washington State Department of Health and the Washington State Office of Financial Management.21,22

ACH, Accountable Community of Health; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RR, rate ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Case data were calculated from March 1, 2020, to June 28, 2020 (closest available date to June 30, 2020) using the “COVID-19 in Washington State: Confirmed Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths by Week of Illness Onset, County, and Age” data set available from the Washington State Department of Health at https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/COVID19/DataDashboard. Counts include females and males

Population estimate calculated using the 2019 postcensal population estimates from the Washington State Office of Financial Management

Infection rates were calculated with Poisson regression with additional clustering by ACH for the statewide estimate

The overall number of SARS-CoV-2 cases through June 28, 2020 was 15,238, but 20 cases were not assigned to an ACH region

The statewide rate ratio is an ACH-weighted state estimate.

Racial and ethnic groups

Among the 240 SARS-CoV-2 cases in pregnancy detected at WA-CPC sites, most cases were among women from racial and ethnic minority groups, including 126 Hispanic women (52.5%), 20 Black women (8.3%), 8 American Indian or Alaska Native women (3.3%), 8 Asian women (3.3%), and 8 Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander women (3.3%) (Table 3 ). Compared with the distribution of women in Washington State who delivered live births in 2018, the proportion of pregnant women from racial and ethnic minority groups with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 2.0- to 3.9-fold higher (Table 3). For example, the proportion of pregnant Hispanic women with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 2.1 times higher (ACH-weighted PR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4–3.1) than the proportion of Hispanic women who delivered live births in 2018 in Washington State (52.5% vs 18.6%) (Table 3). In contrast, the proportion of White and Asian pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection was lower than expected based on 2018 birth data (White ACH-weighted PR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3–1.1; Asian ACH-weighted PR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1–1.5).

Table 3.

Race and ethnicity among pregnant patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections compared with individuals in Washington State

| Variable | Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative (N=240)a | Washington State 2018 live births (N=86,046)b | PRc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity | n | (%) | (95% CI) | n | (%) | PR | (95% CI) |

| Hispanic | 126 | (52.5) | (11.9–90.7) | 16,010 | (18.6) | 2.1 | (1.4–3.1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic | 8 | (3.3) | (0.1–16.2) | 1206 | (1.4) | 3.8 | (1.3–9.7) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 8 | (3.3) | (0.3–12.6) | 8843 | (10.3) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | 8 | (3.3) | (0.4–11.6) | 1195 | (1.4) | 3.9 | (0.8–13.0) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 20 | (8.3) | (0.3–36.4) | 4151 | (4.8) | 2.0 | (1.1–3.7) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 51 | (21.3) | (5.8–46.9) | 49,513 | (57.6) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.1) |

| Multiracial or otherd | 5 | (2.1) | (0.04–11.8) | 3772 | (4.4) | 1.3 | (0.4–3.1) |

| Unknown | 14 | (5.8) | (1.1–17.0) | 1356 | (1.6) | 5.9 | (2.4–13.3) |

Adapted from Washington State Department of Health.18

ACH, Accountable Community of Health; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PR, prevalence ratio; WA-DOH, Washington State Department of Health.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Estimated with clustering by ACH region

2018 data from the WA-DOH’s birth data dashboard tool (Birth Certificate Data, 2000–2018, Community Health Assessment Tool)

Prevalence ratios and 95% CI were ACH weighted

For the Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative, data were abstracted from the medical records. The “other” category reflects the patient’s self-reported designation of their race and ethnicity to the healthcare provider. The WA-DOH data do not include an “other” category.

There were similar racial and ethnic disparities observed when focusing on King and Greater Columbia ACH regions, which experienced the worst SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks during the study period and where the WA-CPC had the highest coverage (Table 1; Supplemental Table 5). In the King ACH region, there was a 2.4-fold higher prevalence of Hispanic women (95% CI, 1.6–3.4; 30.9% vs 13.1%) and 2.1-fold higher prevalence of Black women (95% CI, 1.2–3.3; 19.2% vs 9.3%) with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy compared with the distribution of race and ethnicity of women who delivered live births in the ACH region in 2018. In contrast, the proportion of White pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 50% lower than the proportion of pregnant Black patients expected in the King ACH region (PR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.7; 22.3% vs 47.1%). In the Greater Columbia ACH region, a disproportionate number of cases occurred in Hispanic women compared with the distribution of race and ethnicity of women who delivered live births in the ACH region in 2018 (PR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5–2.4; 85.2% vs 44.4%).

Language used during medical encounters

Among pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 59 (24.6%) received medical care in Spanish and 14 (5.8%) in other languages. The proportion of pregnant patients using a non-English language at WA-CPC sites was higher than the proportion of individuals with limited English proficiency statewide (WA-CPC crude estimate of 30.4% vs WA State of 7.6%). This prevalence difference in the use of a non-English language was observed in the King and Greater Columbia ACH regions. In the King ACH region, 26.6% (25 of 94) of pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were provided care in a non-English language compared with 10.6% of all individuals who received care in the ACH region with limited English proficiency (95% CI, 10.4–10.8).20 In the Greater Columbia ACH region, 34.1% (30 of 88) of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection were provided care in a non-English language compared with 12.0% of individuals in the region with limited English proficiency (95% CI, 11.6–12.3).20

Discussion

Principal findings

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 70% higher in pregnant patients than in similarly aged adults in Washington State (Supplemental Video). The infection rate remained 30% higher after excluding pregnant patients whose SARS-CoV-2 infections were detected through asymptomatic screening strategies, including preprocedure and universal screening at delivery. In addition, we detected significant disparities in the proportion of pregnant women from racial and ethnic minority groups with SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly among Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native pregnant patients; furthermore, a disproportionate number of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection received medical care in a non-English language. The higher infection rates in pregnant patients coupled with an elevated risk of severe illness and maternal mortality16 , 24 , 25 because of COVID-19 suggests that pregnancy should be considered a high-risk health condition for COVID-19 vaccine allocation in phase 1B across the United States, similar to some US states (ie, Texas,26 New Hampshire,27 New Mexico,28 Alaska29).

Results in the context of what is known

Although pregnancy is not considered an immunosuppressed condition, it is associated with an increased risk of disease severity for some infections and potentially, acquisition risk.30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 However, population-based studies are lacking to compare infection rates in pregnant and nonpregnant patients; furthermore, disentangling behavioral and biologic determinants of infection susceptibility is challenging. Although the increased infection rate in pregnant patients may be largely driven by increased testing, the infection rate of pregnant patients remained elevated compared with the infection rate of the general population in the sensitivity analysis, excluding cases detected through universal testing preprocedure and at delivery admission. Notably, our infection rate estimate, excluding asymptomatic cases, was conservative as we were not able to similarly exclude the infection rate estimate in the general population whose infections were also detected through universal testing before medical procedures. Whether an increased infection rate in pregnancy has a biologic basis or is because of other factors, such as increased testing, greater exposure by living in intergenerational households, working in high-risk occupations (ie, healthcare, teaching, service industries), or selection bias, is unknown.

Our data demonstrated a disproportionate burden of SARS-CoV-2 among non-White pregnant patients in our study population in Washington State. Compared with the distribution of women in Washington State who delivered live births in 2018, the proportion of pregnant women from racial and ethnic minority groups with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 2- to 4-fold higher, with the greatest disparity among Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native pregnant patients. Large disparities in rates of SARS-CoV-2 infections have been reported in the United States for individuals of Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander race or ethnicity.6 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 37 A fundamental cause of health disparities is the socioeconomic inequality that arises from structural racism and decades of limited access to quality healthcare, education, and housing.38 , 39 Pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were also more likely to receive care in a non-English language compared with the statewide prevalence of patients with limited English proficiency receiving care.

Clinical and research implications

These data provide evidence that pregnant individuals may have a higher SARS-CoV-2 infection rate than similarly aged individuals. Whether pregnant patients are truly at a higher risk is yet unknown and exploring mechanisms for a potentially elevated infection risk will be challenging with limited data currently available. However, these data should lead to a greater public health response to prevent infections in pregnant women and to focus efforts on individuals from minority racial and ethnic groups and with limited English proficiency. Culturally appropriate public health messaging focused on preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections in pregnancy, including messages in multiple languages, and services targeting disproportionately affected communities are desperately needed.40 These data should inform research investigating risk factors faced by pregnant individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including household transmission, employment in high-risk occupations (eg, healthcare), and potential biologic determinants of infection susceptibility.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. WA-CPC sites captured 61% of annual deliveries in Washington State, including the vast majority of cases in the ACH regions with the highest SARS-CoV-2 cases reported to the WA-DOH. We included all COVID-19 cases in pregnancy, including all trimesters of pregnancy and hospitalized and nonhospitalized cases, independent of pregnancy outcome. Study limitations included selection bias because of incomplete ascertainment of all pregnancy cases in Washington State. Differences in sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant patients and SARS-CoV-2 testing strategies among participating vs nonparticipating facilities may have introduced bias in infection rate estimates and size of racial and ethnic disparities. Notably, although the WA-DOH captured statewide data, pregnancy status was missing in approximately 35% of case report forms for reproductive-aged females; we may have captured cases not reported to the WA-DOH, but we were unable to estimate the degree of nonoverlap. The ideal comparison group for the WA-CPC SARS-CoV-2 cases in pregnancy would have been nonpregnant reproductive-age females, but data on these women were not collected in our study. Therefore, the best available comparison group for comparing infection rates with reproductive-age females was publicly available WA-DOH data; COVID-19 surveillance data were available by age (presented in 20 year categories) or gender, but not both, necessitating a comparison to females and males between 20 and 39 years.21 In addition, we did not have individual case data for any publicly available data sets, so we were unable to adjust for individual-level characteristics. Pregnant adolescents (<18 years old) were excluded in our study but included in overall delivery numbers; as adolescent pregnancies only account for <1% of births in Washington State, concern for bias due to this exclusion was very low.18 In addition, publicly available WA-DOH data served as imperfect proxies for the ideal denominators for the analyses of racial and ethnic and language disparities. Nonetheless, this study provided statewide and regional assessments of infection rates in pregnancy, including cases from all pregnancy trimesters, and identified pervasive demographic disparities in pregnant individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Conclusions

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, pregnant patients in Washington State had a 70% higher SARS-CoV-2 infection rate than similarly aged adults, which in part reflects a population that was prioritized for testing. However, we can conclude that pregnant patients were not protected in the early months of the pandemic in Washington State by the public health response or through frequent interactions with obstetrical care providers. Furthermore, the greatest burden of infections occurred within racial and ethnic minority groups and patients preferring to receive care in a non-English language. Understanding the geographic, racial and ethnic, and language distributions of SARS-CoV-2 infections among pregnant patients would enable targeting the public health response to pregnant patients at the greatest risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated adverse maternal-fetal outcomes.11 , 19 , 24 , 41, 42, 43 Broader recognition that pregnancy is a risk factor for severe illness and maternal mortality16 , 24 , 25 coupled with a higher infection rate in pregnancy strongly suggested that pregnant people should be broadly prioritized for COVID-19 vaccine allocation in the United States similar to some states.26, 27, 28, 29

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the pregnant patients contributing data to this article and our partners across Washington State that enabled this investigation. We note that we have shown single names for groups, such as “Hispanic” or “American Indian or Alaska Native,” which reflected an inclusive approach to naming, but does not capture the spectrum of diversity in ancestry and cultural and behavioral and linguistic differences. We also recognize the differences between sex and gender, noting that the term “women” is not inclusive for biologically born female individuals that identify as nonbinary or transgender. Labels and words are imperfect, and ethnic, cultural, and gender groups are sometimes overlapping or mischaracterized by single words or names. We apologize if offense is taken regarding group names used in the manuscript.

We thank Ms Jane Edelson, who provided expert assistance with project management at the University of Washington and was compensated on an hourly rate through the Institute for Translational Health Sciences. Ms Adrienne Meyer with the University of Washington Human Subjects Division provided critical assistance to obtain reliance agreements with community institutional review boards. Barbara James, BSN, RNC, graciously provided coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) case counts for PeaceHealth Southwest. We thank Robert Weston, MD, and Erin Andreas, RN, for reporting COVID-19 cases at Mid-Valley Hospital. Peter Napolitano, MD, provided assistance with patient identification at the University of Washington Yakima site. We also thank Hanna Oltean, MPH, at the Washington State Department of Health (WA-DOH), Office of Communicable Disease Epidemiology, for providing the WA-DOH data regarding severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 cases reported to the DOH by each Accountable Community of Health region. We are grateful to Nicole Wothe for administrative assistance with this manuscript. Lastly, we thank Ronit Katz, DPhil, at the University of Washington for biostatistical consultations.

Footnotes

G.G.T. and E.M.H. contributed equally to this work.

A.K. is on the Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline advisory board for immunization, which is unrelated to the content of this article. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

This work was supported primarily by funding from the University of Washington Population Health Initiative, the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Washington, and by philanthropic gift funds. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant numbers AI133976, AI145890, AI143265, and HD098713 to K.A.W.; HD001264 to A.K.; and AI120793 to S.M.L.). Study data were managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted by the Institute of Translational Health Sciences at the University of Washington, which was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR002319). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funders.

Cite this article as: Lokken EM, Taylor GG, Huebner EM, et al. Higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;225:75.e1-16.

Appendix

Supplemental Figure.

Video still

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Supplemental Table 1.

Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative participating sites

| Number | Participating site |

|---|---|

| 1 | University of Washington Medical Center: Montlake |

| 2 | University of Washington Medical Center: Northwest |

| 3 | Swedish: Issaquah |

| 4 | Swedish: First Hill |

| 5 | Swedish: Ballard |

| 6 | Swedish: Edmonds |

| 7 | University of Washington Valley Medical Center |

| 8 | MultiCare: Covington Medical Center |

| 9 | MultiCare: Auburn Medical Center |

| 10 | MultiCare: Tacoma General Hospital |

| 11 | MultiCare: Good Samaritan Hospital |

| 12 | MultiCare: Spokane Valley Hospital |

| 13 | MultiCare: Deaconess Medical Center |

| 14 | EvergreenHealth Medical Center—Kirkland |

| 15 | PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center—Bellingham |

| 16 | Providence Regional Medical Center—Everett |

| 17 | Jefferson Medical Center |

| 18 | Legacy Salmon Creek Medical Center |

| 19 | Virginia Mason Memorial Hospital |

| 20 | Central WA Hospital, Confluence |

| 21 | UW Medicine Maternal Fetal Medicine Clinic at Yakima |

| 22 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Valley Vista Medical Group |

| 23 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Pasco Miramar Health Center |

| 24 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Unify Community Health, Mission Avenue |

| 25 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Unify Community Health, West Central Community Center |

| 26 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Unify Community Health, Northeast Community Center |

| 27 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Grandview Medical-Dental Clinic |

| 28 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Lincoln Avenue Medical Dental |

| 29 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Yakima Medical Dental Clinic |

| 30 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Mountain View Women's Clinic |

| 31 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Toppenish Medical Dental Clinic |

| 32 | Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinics: Family Medical Center Walla Walla |

| 33 | Vancouver Clinic |

| 34 | PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center |

| 35 | Mid-Valley Hospital |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Supplemental Table 2.

Data source descriptions

| Data source | Population | Dates | Data available or used | Purpose | Other details | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WA-CPC | 240 cases of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant patients aged ≥18 y in Washington State at 35 hospitals and clinics | March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020 | Demographic and clinical data retrospectively abstracted from medical records |

|

WA-CPC sites capture ∼61% of annual deliveries in Washington State | N/A |

| WA-DOH: SARS-CoV-2 case counts in pregnancy | 346 cases of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant patients aged 18–50 y across Washington State | March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020 | Number of cases by ACH region |

|

Individual-level data on each case was not publicly available | N/A |

| Pregnancy status was ascertained through case interviews and by local health department investigation |

|

35% of SARS-CoV-2 case records among females aged 18–50 y contained unknown or missing pregnancy status |

Data (case counts) acquired through written communication with the WA-DOH (Hanna Oltean, MPH) |

|||

| WA-DOH birth data dashboard tool: Birth Certificate Data 2018 | Data on live births in Washington State in 2018 at ACH regional and state levels; all maternal ages included | 2018 | Number of live births, maternal race and ethnicity distribution |

|

Individual-level data on each live birth in 2018 was not publicly available |

https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/HealthDataVisualization/BirthDashboards/AllBirthsACH Accessed Aug. 21, 2020 |

| WA-DOH: COVID-19 dashboard (confirmed cases by week of Illness onset, county, and age) | Cases of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 reported to the WA-DOH; males and females aged 20–39 y | March 1, 2020, to June 28, 2020 | Number of cases by ACH region |

|

Data were available by age or gender, not both | https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/COVID19/DataDashboard |

| Individual-level data on each case were not publicly available |

Accessed Sept. 7, 2020 |

|||||

| Washington State Office of Financial Management | Postcensal population estimates for patients aged 20–39 y | 2019 | Population estimates by ACH region and statewide |

|

https://www.ofm.wa.gov/washington-data-research/population-demographics/population-estimates/estimates-april-1-population-age-sex-race-and-hispanic-origin Published 2020 Accessed Sept. 21, 2020 |

|

| WA-DOH: ACH social determinants of health dashboard | Percentage of Washington State individuals aged >5 y with limited English language proficiency (those who speak English “less than very well”) | 2014–2017 | Proportion of individuals by ACH region and statewide with limited English language proficiency |

|

No count data were available on the WA-DOH website. Only prevalence estimates were available, which limited the ability to generate 95% confidence intervals around comparative point estimates | https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/HealthDataVisualization/SocialDeterminantsofHealthDashboards/ACHSocialDeterminantsofHealth |

| Language data were collected as part of the American Community Survey |

Accessed Sept. 17, 2020 |

ACH, Accountable Communities of Health; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; N/A, not applicable; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WA-CPC, Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative; WA-DOH, Washington State Department of Health.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Supplemental Table 3.

Infection rates in pregnancy—sensitivity analysis estimating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rates using WA-DOH case counts and 2018 birth data

| ACH region | WA-DOH–reported cases in pregnancy |

Washington State: 20–39 y |

RR |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases in pregnancya |

Estimated deliveries during the study periodb n |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 deliveries |

Casesc |

Populationd n |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 |

|||||||

| n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |||

| Better Health Together or North Central | 23 | (6.6) | 3376 | 6.8 | (4.3–10.2) | 1746 | (11.5) | 214,300 | 8.1 | (7.8–8.5) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) |

| Greater Columbia | 135 | (39.0) | 3146 | 42.9 | (3.6–5.1) | 5459 | (35.8) | 193,851 | 28.2 | (27.4–28.9) | 1.5 | (1.3–1.8) |

| King | 98 | (28.3) | 8112 | 12.1 | (9.8–14.7) | 4274 | (28.0) | 744,386 | 5.7 | (5.6–5.9) | 2.1 | (1.7–2.6) |

| North Sound | 60 | (17.3) | 4755 | 12.6 | (9.6–16.2) | 1752 | (11.5) | 325,671 | 5.4 | (5.1–5.6) | 2.3 | (1.8–3.0) |

| Pierce | 20 | (5.8) | 3821 | 5.2 | (3.2–8.1) | 1173 | (7.7) | 239,814 | 4.9 | (4.6–5.2) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) |

| SW Washington State Regional Health, Olympic, or Cascade Pacific Action Alliance | 10 | (2.9) | 5458 | 1.8 | (0.9–3.4) | 834 | (5.5) | 358,226 | 2.3 | (2.2–2.5) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.4) |

| Washington State total | 346 | 28,682 | 12.1 | (10.8–13.4)e | 15,238f | 2,076,248 | 7.3 | (7.2–7.4) | 1.7 | (1.4–2.2)g | ||

Adapted from Washing State Department of Health and Washing State Office of Financial Management.18,22

ACH, Accountable Communities of Health; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RR, rate ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WA-DOH, Washington State Department of Health.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Case counts of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases among females aged 18 to 50 years who were pregnant at the time of infection were provided by the WA-DOH from March 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Pregnancy status was ascertained through case interviews or by local health jurisdiction investigation. In 35% of SARS-CoV-2 case records among females aged 18 to 50 years, pregnancy status was unknown or missing pregnancy

Statewide live births were estimated from March 2020 to June 2020 using the Washington State 2018 birth data specifically by estimating 4 months of annual births using the ACH-specific and overall total births from 2018 birth dashboard (Birth Certificate Data, 2000–2018, Community Health Assessment Tool at https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/HealthDataVisualization/BirthDashboards/AllBirthsACH)

Case data were calculated from March 1, 2020, to June 28, 2020 (closest available date to June 30, 2020) using the “COVID-19 in Washington State: Confirmed Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths by Week of Illness Onset, County, and Age” data set available from the WA-DOH at https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/COVID19/DataDashboard. Counts include females and males

Population estimate calculated using the 2019 postcensal population estimates from the Washington State Office of Financial Management

Infection rates were calculated with Poisson regression with additional clustering by ACH region for the statewide estimate

The overall number of SARS-CoV-2 cases through June 28, 2020, was 15,238, but 20 cases were not assigned to an ACH region

The statewide rate ratio is an ACH-weighted state estimate.

Supplemental Table 4.

Infection rates in pregnancy—sensitivity analysis excluding cases detected by asymptomatic screening (preprocedure and universal testing at delivery admission) at WA-CPC sites

| ACH region | WA-CPC |

Washington State: 20–39 y |

RR |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases in pregnancy |

Deliveries during the study period n |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 deliveries |

Casesa |

Populationb n |

SARS-CoV-2 infection rate per 1000 |

|||||||

| n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | n | (%) | Rate | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | |||

| Better Health Together or North Central | 9 | (4.6) | 1318 | 6.8 | (3.6–13.1) | 1746 | (11.5) | 214,300 | 8.1 | (7.8–8.5) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) |

| Greater Columbia | 78 | (40.0) | 2653 | 29.4 | (23.5–36.7) | 5459 | (35.8) | 193,851 | 28.2 | (27.4–28.9) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.3) |

| King | 72 | (36.9) | 7283 | 9.9 | (7.8–12.4) | 4274 | (28.0) | 744,386 | 5.7 | (5.6–5.9) | 1.7 | (1.3–2.2) |

| North Sound | 14 | (7.2) | 2506 | 5.6 | (3.3–9.4) | 1752 | (11.5) | 325,671 | 5.4 | (5.1–5.6) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) |

| Pierce | 14 | (7.2) | 1696 | 8.3 | (4.9–13.9) | 1173 | (7.7) | 239,814 | 4.9 | (4.6–5.2) | 1.7 | (0.9–2.8) |

| SW Washington State Regional Health, Olympic, or Cascade Pacific Action Alliance | 8 | (4.1) | 1777 | 4.5 | (2.3–9.0) | 834 | (5.5) | 358,226 | 2.3 | (2.2–2.5) | 1.9 | (0.8–3.8) |

| Washington State total | 195 | 17,233 | 11.3 | (6.3–20.3)c | 15,238d | 2,076,248 | 7.3 | (7.2–7.4) | 1.3 | (0.96–1.90)e | ||

ACH, Accountable Communities of Health; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RR, rate ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WA-CPC, Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Case data were calculated from March 1, 202, to June 28, 2020 (closest available date to June 30, 2020) using the “COVID-19 in Washington State: Confirmed Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths by Week of Illness Onset, County, and age” data set available from the Washington State Department of Health at https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/COVID19/DataDashboard. Counts include females and males

Population estimate calculated using the 2019 postcensal population estimates from the Washington State Office of Financial Management

Infection rates were calculated with Poisson regression with additional clustering by ACH region for the statewide estimate

The overall number of SARS-CoV-2 cases through June 28, 2020, was 15,238, but 20 cases were not assigned to an ACH region

The statewide rate ratio is an ACH-weighted state estimate.

Supplemental Table 5.

Comparison of racial and ethnic disparities among pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 compared by Washington State King and Greater Columbia ACH regions

| Variable | King ACH regiona |

Greater Columbia ACH regiona |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WA-CPCSARS-CoV-2case counts(N=94) | King ACH 2018 live births (N=24,347)b | PRc | WA-CPCSARS-CoV-2case counts(N=88) | Greater Columbia ACH 2018 live births(N=9,438)b | PRc | |||||||||

| Race and ethnicity | n | (%) | (95% CI) | n | (%) | PR | (95% CI) | n | (%) | (95% CI) | n | (%) | PR | (95% CI) |

| Hispanic | 29 | (30.9) | (21.7–41.2) | 3181 | (13.1) | 2.4 | (1.6–3.4) | 75 | (85.2) | (76.1–91.9) | 4195 | (44.4) | 1.9 | (1.5–2.4) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic | — | — | — | 129 | (0.5) | — | — | — | — | — | 195 | (2.1) | — | — |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | — | — | — | 5565 | (22.9) | — | — | — | — | — | 202 | (2.1) | — | — |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic | — | — | — | 376 | (1.5) | — | — | — | — | — | 10 | (0.1) | — | — |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 18 | (19.2) | (11.8–28.6) | 2252 | (9.3) | 2.1 | (1.2–3.3) | — | — | — | 63 | (0.7) | — | — |

| White, non-Hispanic | 21 | (22.3) | (14.4–32.1) | 11,455 | (47.1) | 0.5 | (0.3–0.7) | — | — | — | 4204 | (44.5) | — | — |

| Multiracial or other | — | — | — | 981 | (4.0) | — | — | — | — | — | 201 | (2.1) | — | — |

| Unknown | 10 | (10.6) | (5.2–18.7) | 398 | (1.6) | 6.5 | (3.1–12.1) | — | — | — | 368 | (3.9) | — | — |

ACH, Accountable Communities of Health; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PR, prevalence ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WA-CPC, Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative; WA-DOH, Washington State Department of Health.

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

For ACH-specific analyses, race and ethnicity data were repressed when there were fewer than 10 cases in alignment with the WA-DOH reporting guidelines to protect privacy

2018 data from the WA-DOH’s birth data dashboard tool (Birth Certificate Data, 2000–2018, Community Health Assessment Tool).

Prevalence ratios and 95%CI were ACH-weighted.

Supplementary Data

The Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative infection rates

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.

References

- 1.Wiersinga W.J., Rhodes A., Cheng A.C., Peacock S.J., Prescott H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D’Alton M., Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell K.H., Tornatore J.M., Lawrence K.E., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among patients admitted for childbirth in Southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520–2522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaCourse S.M., Kachikis A., Blain M., et al. Low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among pregnant and postpartum patients with universal screening in Seattle, Washington. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa675. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahoy M.J., Whitaker M., O’Halloran A., et al. Characteristics and maternal and birth outcomes of hospitalized pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 13 states, March 1-August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1347–1354. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellington S., Strid P., Tong V.T., et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:769–775. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panagiotakopoulos L., Myers T.R., Gee J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospitalized pregnant women: reasons for admission and pregnancy characteristics - eight U.S. health care centers, March 1-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1355–1359. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodworth K.R., O’Malley Olsen E., Neelam V., et al. Birth and infant outcomes following laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy - SET-NET, 16 Jurisdictions, March 29-October 14, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1635–1640. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adhikari E.H., Moreno W., Zofkie A.C., et al. Pregnancy outcomes among women with and without severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce-Williams R.A.M., Burd J., Felder L., et al. Clinical course of severe and critical coronavirus disease 2019 in hospitalized pregnancies: a United States cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100134. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight M., Bunch K., Vousden N., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore J.T., Ricaldi J.N., Rose C.E., et al. Disparities in incidence of COVID-19 among underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in counties identified as hotspots during June 5-18, 2020—22 states, February-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1122–1126. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatcher S.M., Agnew-Brune C., Anderson M., et al. COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska Native persons—23 states, January 31-July 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1166–1169. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6934e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emeruwa U.N., Spiegelman J., Ona S., et al. Influence of race and ethnicity on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection rates and clinical outcomes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1040–1043. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tai D.B.G., Shah A., Doubeni C.A., Sia I.G., Wieland M.L. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zambrano L.D., Ellington S., Strid P., et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proclamation by the governor amending proclamation 20–05: 20–25 stay home—stay healthy. State of Washington, Office of the Governor; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Washington State Department of Health Birth Certificate Data, 2000–2018, Community Health Assessment Tool (CHAT) 2019. https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/HealthDataVisualization/BirthDashboards/AllBirthsACH Available at: Accessed August 21, 2020.

- 19.Lokken E.M., Walker C.L., Delaney S., et al. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:911.e1–911.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Washington State Department of Health Accountable Communities of Health (ACH) social determinants of health dashboards. 2020. https://www.doh.wa.gov/DataandStatisticalReports/HealthDataVisualization/SocialDeterminantsofHealthDashboards/ACHSocialDeterminantsofHealth Available at: Accessed September 17, 2020.

- 21.Washington State Department of Health COVID-19 data dashboard. 2020. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/COVID19/DataDashboard Available at: Accessed September 7, 2020.

- 22.Washington State Office of Financial Management Estimates of April 1 population by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. 2020. https://www.ofm.wa.gov/washington-data-research/population-demographics/population-estimates/estimates-april-1-population-age-sex-race-and-hispanic-origin Available at: Accessed September 21, 2020.

- 23.Oltean H. Personal communication. Washington State Department of Health.

- 24.Lokken E.M., Huebner E.M., Taylor G.G., et al. Disease severity, pregnancy outcomes and maternal deaths among pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.12.1221. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jering K.S., Claggett B.L., Cunningham J.W., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized women giving birth with and without COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.9241. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Texas Department of State Health Services COVID-19 vaccine allocation phase 1B definition. https://www.dshs.texas.gov/coronavirus/immunize/vaccine/EVAP-Phase1B.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 27.Bureau of Infectious Disease Control NH COVID-19 Vaccination Allocation Guidelines for Phase 1b. 2021. https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/cdcs/covid19/documents/phase-1b-technical-assistance.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 28.New Mexico Department of Health: State of New Mexico COVID-19 vaccine allocation plan phases 1A, 1B, 1C, and 2. 2021. https://cv.nmhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2021.1.8-DOH-Phase-Guidance.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 29.Alaska Department of Health and Social Services COVID-19 vaccine allocation: Phase 1b. 2020. http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Epi/id/SiteAssets/Pages/HumanCoV/DHSS_VaccineAllocation_Phase1b.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 30.Kourtis A.P., Read J.S., Jamieson D.J. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2211–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce M., Kurinczuk J.J., Spark P., Brocklehurst P., Knight M., Ukoss Perinatal outcomes after maternal 2009/H1N1 infection: national cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d3214. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siston A.M., Rasmussen S.A., Honein M.A., et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303:1517–1525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomson K.A., Hughes J., Baeten J.M., et al. Increased risk of HIV acquisition among women throughout pregnancy and during the postpartum period: a prospective per-coital-act analysis among women with HIV-infected partners. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:16–25. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mofenson L.M. Risk of HIV acquisition during pregnancy and postpartum: a call for action. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:1–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hensley M.K., Bauer M.E., Admon L.K., Prescott H.C. Incidence of maternal sepsis and sepsis-related maternal deaths in the United States. JAMA. 2019;322:890–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasmussen S.A., Jamieson D.J. What obstetric health care providers need to know about measles and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:163–170. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Washington State Department of Health COVID-19 morbidity and mortality by race, ethnicity and language in Washington State. 2020. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1600/coronavirus/RaceReport20200702.pdf Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 38.Cleveland Manchanda E., Couillard C., Sivashanker K. Inequity in crisis standards of care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2011359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Addressing health equity during the COVID-19 pandemic: position statement. 2020. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/position-statements/2020/addressing-health-equity-during-the-covid-19-pandemic Available at: Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 40.Thakur N., Lovinsky-Desir S., Bime C., Wisnivesky J.P., Celedón J.C. The structural and social determinants of the racial/ethnic disparities in the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic. What’s our role? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:943–949. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1523PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savasi V.M., Parisi F., Patanè L., et al. Clinical findings and disease severity in hospitalized pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:252–258. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hantoushzadeh S., Shamshirsaz A.A., Aleyasin A., et al. Maternal death due to COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:109.e1–109.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirshberg A., Kern-Goldberger A.R., Levine L.D., et al. Care of critically ill pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Washington State COVID-19 in Pregnancy Collaborative infection rates

Lokken et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021.