Abstract

Most U.S. universities have made explicit commitments to educating economically diverse student bodies; however, the higher education system is highly stratified. In this paper, we seek to understand stratification in the wake of the Great Recession by examining enrollment among students from differing income backgrounds by institutional type. Two theoretical frameworks suggest different conclusions. A Disaster Capitalism framework suggests that in places where the recession was most severe, enrollment by income would become more stratified than in places where the downturn was less severe. In contrast, Effectively Maintained Inequality would suggest that enrollments were already effectively stratified by income and would not necessarily be sensitive to exposure to an economic shock. Employing fixed effects modeling and novel data based on the tax records of 30 million Americans, we examine income composition by institutional type from 2004 to 2012. We find that although stratification by institutional type worsened during the recession and subsequent recovery, patterns of economic stratification were not more intense for institutions that enrolled students from states hardest hit by the recession. We conclude that these patterns are consistent with an Effectively Maintained Inequality framework. During the recession, the top quintiles continued to enjoy their longstanding disproportionate enrollment in the most selective institutions. For the bottom quintiles, the longstanding marginalization from 4-year college going persisted through the recession. These stratification patterns, however, were not more pronounced in places hardest hit by the recession.

Keywords: Higher education, Great recession, Stratification, Institutional type, Income quintiles

Introduction

An economic shock, like the Great Recession, offers a unique opportunity to understand the response of families and higher education institutions to stressful economic conditions. Prior research indicates the recession had differential impacts on family spending on education (Kornrich and Lunn 2013), student achievement (Shores and Steinberg 2017), higher education endowments (Goetzmann and Oster 2014), federal and state financial aid (Bettinger and Williams 2013), and overall enrollments by institutional type (Barr and Turner 2013). The recession hit some states and localities particularly hard (Shoag and Veuger 2016; Slack and Myers 2014), yet we know relatively little about how the intensity of the recession in particular areas shaped higher education enrollments. Enrollment, both if and where students attend, is of great importance because it is a primary way to understand patterns of access to higher education.

Drawing on data on the economic composition of colleges from Opportunity Insights based on the tax records of 30 million Americans to examine enrollments by income quintile, this study contributes a more nuanced perspective on economic stratification in higher education in years leading up to and immediately following the Great Recession. Did variation in recession intensity across states (drawn from the K-12 literature, see Shores and Steinberg 2017) shape higher education enrollment patterns? Using competing frameworks of Disaster Capitalism and Effectively Maintained Inequality (EMI), we examine how economic stratification in enrollment in different higher education institutional types varied by the level of intensity of the Great Recession.

The global recession that is due to follow the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to hit US higher education particularly hard. Steep declines are expected in state appropriations (which never fully rebounded from the Great Recession) (Laderman et al. 2018), tuition, and other revenue sources. With state revenues expected to decline, policymakers in some states moved to reduce funding that had already been budgeted for public colleges and universities (Hancock et al. 2020; Munoz 2020), Colleges and universities have responded to economic uncertainty with efforts to reduce costs, with some institutions implementing hiring freezes and taking other similar measures to limit spending (Flaherty 2020; Ruf 2020). This study, which focuses on the last major recession, offers insight into stratification in enrollment patterns that may emerge as the nation prepares for another economic downturn.

Relevant Literature

Stratification in the American higher educational system is a well-documented phenomenon. Using data that describe trends largely in the years before the Great Recession, researchers have demonstrated that the American higher education system was stratified by economic class, with children from high-income families disproportionately attending selective private and public flagship institutions (Astin and Oseguera 2004; Bastedo and Jaquette 2011; Ford and Thompson 2016; Hearn and Rosinger 2014; Posselt et al. 2012; Roksa et al. 2007). Children from low-income households are over-represented in non-selective institutions, especially 2-year and for-profit colleges (Carnevale and Rose 2004; Carnevale and Strohl 2013). These stratified institutional types are associated with a wide variety of on-campus resources, student experiences, and labor market outcomes. Highly selective institutions have far more donative resources with which to both subsidize their students and provide resources for an expanded and enriched student experience (Hoxby 2009; Winston 2004). As a result, selective universities are able to spend more on instruction, student services, and academic support (Carnevale and Strohl 2013; Hoxby 2009). Furthermore, this gap in resources and expenditures has increased over time, accompanied by a growing divide in student outcomes at selective and non-selective institutions (Bound et al. 2010).

Graduates from different institutional types differ in their labor market outcomes. Generally, graduation from a more selective institution is positively correlated with adult earnings (Mayhew et al. 2016; Witteveen and Attewell 2017; Zhang 2012). This wage bump is larger for low-income and students of color than for higher-income and white students1 (Dale and Krueger 2002, 2014; Monks 2000). Students who graduate from elite and highly selective universities are more likely to be invited for a job interview than graduates with identical resumes who attended less selective institutions in the same local region (Gaddis 2014). In highly competitive fields like investment banking, hiring committees reward applicants who attended their alma maters with interviews and job offers (Rivera 2016).

The Great Recession

The impact of the Great Recession was not evenly distributed across geographic localities or economic classes. Low-income families were disproportionately affected and experienced high unemployment rates and loss in home equity (Hendey et al. 2012; Nichols and Simms 2012; Pfeffer et al. 2013). They were slower to experience the effects of the economic recovery or did not experience any recovery at all (Kochhar and Fry 2014). In the years following the recession, 95% of income gains went to the top 1% (Saez 2013).

The recession also exacerbated existing geographic inequalities, as the impact of the recession differed across states and counties within states (Thiede and Monnat 2016). States with struggling economies before the recession were both the hardest hit and the slowest to recover (Shoag and Veuger 2016; Slack and Myers 2014). Differences among states were considerable, with the most deeply affected states seeing increases in unemployment of 6% or more from 2006 to 2009, while unemployment rates in less affected states increased by less than 2% (Shoag and Veuger 2016). Rural counties did not experience as dramatic a rise in unemployment as urban counties but were slower to recover as the recession ended (Thiede and Monnat 2016). Recovery from the recession has been uneven, with some states struggling to regain pre-recession levels of employment and some counties not recovering at all (Slack and Myers 2014; Thiede and Monnat 2016). In general, this recession was the most severe, with the slowest recovery, of any yet in the post-war economy (Elsby et al. 2010; Hoynes et al. 2012).

The higher education sector did not escape the impacts of the Great Recession. Public and private institutions were both affected, in differing ways, by the economic downturn. States slashed appropriations for public colleges and universities (Barr and Turner 2013; Mulhern et al. 2015). Private institutions, which depend in part on the interest drawn from their endowments, saw huge losses (Brown et al. 2014). The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), the major piece of federal legislation passed to mitigate the effects of the recession, contributed to stratifying institutions. ARRA funds earmarked for higher education institutions were mainly directed toward research and development grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation. These funds, policymakers argued, were necessary because investment in science and medical research had the potential to drive economic growth. In 2010, private research universities received five times more ARRA allocations than public research universities (Taylor and Cantwell 2016). In contrast, universities with the lowest research productivity received substantially smaller slices of the recovery act pie. For example, community colleges received almost no ARRA funding (Douglass 2010). This funding stream flowed to institutions that already had more resources and advantages—increasing the stratification of financial resources by institutional type during the post-recession period.

With decreases in state appropriations and massive endowment losses, the price of college attendance rose in the wake of the Great Recession as colleges sought to increase revenues through tuition dollars. Tuition increased 27% at public four-year colleges and 24% at two-year colleges (Long 2014). While there was significant expansion of the federal Pell Grant program to support low-income students during this period, amid declining state support and renewed investments in federal aid, many states scaled back their financial aid programs (Bettinger and Williams 2013). The average price of college for students and their families increased during this period by $360 per year (Long 2014). In spite of rising prices, enrollments in postsecondary education expanded, particularly in states where the effects were most intense (Barr and Turner 2013; Dunbar et al. 2011; Long 2014). Two-year and for-profit institutions saw enrollment gains, perhaps because these institutions are often non-selective and have the flexibility to expand capacity quickly in a way that more selective institutions cannot or do not do (Barr and Turner 2013). While these studies found differences in enrollment growth by institutional type, they do not examine student economic compositional differences nor differences by recession intensity, two key areas where this paper contributes.

Competing Conceptual Frameworks: Disaster Capitalism or Effectively Maintained Inequality?

Two theoretical frameworks suggest different outcomes for the stratification of class-based higher education enrollments in the aftermath of an economic shock like the Great Recession. Disaster Capitalism, a framework pioneered by Naomi Klein (2007), suggests that in the wake of a disaster or large economic shock, social stratification will worsen because organizations and people with economic advantages will be best poised to benefit in the chaotic aftermath. Compounding this, Disaster Capitalism posits, large shocks can displace and create more obstacles for organizations and people who were already in precarious economic positions. Disaster Capitalism has been used as a framework to examine stratification after natural disasters (e.g., Hurricane Katrina, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan). It has also been applied to understanding the inequities that ensue after a large interruption in a social system or market (for example, Mexico’s drug-war (Schneck 2012), the Global housing crisis (Aalbers 2015), and global economic shocks (Hooren et al. 2014)). If a Disaster Capitalism2 framework applies to higher education enrollments after the Great Recession, we would expect to see class stratification vary by the intensity of the shock. For example, at colleges where students experienced the shock of the economic downturn most severely, we would expect to see more stratification of students by institutional types than in places where the economic shock was felt less severely.

The mechanisms underlying increased higher education stratification are many and varied. For example, institutions might be hit by decreases in state funding or evaporating endowment funds, which would in turn lead to less aid money (and higher tuition) for students. The need for more tuition revenue could lead institutions to recruit and admit wealthier or out-of-state students (Han et al. 2019; Jaquette and Salazar 2018; Jaquette and Curs 2015), at the expense of enrolling low-income and minoritized students (Jaquette et al. 2016). On the demand side, the recession may have made families more sensitive to prices in ways they may not otherwise have been. For example, they may “trade down” from national universities and attend a regional university or start at a community college with the intention of transferring later. During especially troubled economic times like the Great Recession, in which both families and higher education institutions face financial pressures, a Disaster Capitalism scenario might occur. That is, in the wake of the shock of an economic downturn, the highest-income families would be buffered from the harshest effects and would increase attendance at elite and selective universities and higher priced private institutions while students from families in the lowest economic quintiles would be consolidated further into the least selective and public higher education options. For these reasons, it is plausible that a Disaster Capitalism framework, in which class stratification increases in places hardest hit by the recession, could describe higher education enrollments after the Great Recession.

A competing framework, Effectively Maintained Inequality (EMI) theory, would predict that stratification would be maintained through the Great Recession. Long before the economic shock, advantaged families were already securing qualitatively better opportunities at every level of education. Lucas (2001) asserts that children from families with socioeconomic advantages not only attain higher levels of education (vertical stratification), they also secure the highest quality educational opportunities at each level of schooling (horizontal stratification). EMI has been used to understand patterns of secondary school placement: advantaged families tend to secure qualitatively better experiences for their children in the form of Advanced Placement tracks, gifted-and-talented-programs, and magnet/exam schools (e.g., Klugman 2013; Weis et al. 2014). These horizontal stratification processes were already in place well before the Great Recession. The theory of Effectively Maintained Inequality has primarily been applied to K-12 contexts, and we seek to build on early EMI work in the higher education literature (e.g., Minor 2008; Posselt et al. 2012; Wolniak et al. 2016).

In the higher education context, EMI theory identifies ways that families with the most resources and advantages secure qualitatively better higher education opportunities. Examples of college characteristics upon which higher education institutions are horizontally stratified include endowments, selectivity, and graduation rates (Gerber and Cheung 2008). In this paper, we examine institutional stratification by levels of selectivity. On average, highly selective institutional types tend to offer more resources and confer more advantages on students than less selective institutions (Bowen et al. 2009; Carnevale and Rose 2004; Melguizo 2010). If EMI is a better framework for describing how the system operated after the economic shock of the Great Recession, we would expect patterns of stratification to be maintained across the whole higher education system during this period but not necessarily vary in severity by where the shock of the recession hit hardest.3 Given these competing conceptual frameworks and consideration of the extant literature, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How did years leading up to and following the Great Recession shape higher education enrollments by institutional type for students from differing income backgrounds?

RQ2: How did the varying intensity of the Great Recession shape higher education enrollments by institutional type for students from differing income backgrounds?

Our findings will support a Disaster Capitalism framing if the economic shock of the Great Recession exacerbated patterns of economic stratification of students into stratified institutional types. Our findings will be in line with an EMI framework if the inequities that were already in place before the recession continue in a “business as usual” manner.

Data and Methods

Sample, Data Sources, and Variables

Our sample included 1212 public and private not-for-profit 4-year colleges4 and universities in the United States. We limited the sample to colleges that receive Title IV funding via federal student aid programs and are required to report data to the Department of Education. We observed colleges annually from the 2003–2004 to the 2011–2012 academic years. In our analyses, we estimated models for all sample colleges and by institutional selectivity (elite and highly selective, selective, and non-selective as defined by Barron’s Profile of American Colleges) to examine stratification patterns between less selective and more selective colleges, which tend to be characterized by more on-campus resources, higher graduation rates, and better labor market outcomes among graduates (e.g., Hout 2012; Winston 1999, 2004; Witteveen and Attewell 2017; Zhang 2012). Elite and highly selective colleges were identified as “highly” and “most” competitive by Barron’s (2008); selective colleges were identified as “very” competitive and competitive; and non-selective were identified as “less” and “not” competitive institutions. We also examined enrollment separately for public and private colleges within each selectivity grouping to account for variations in funding structures, student markets, and missions that could shape enrollment patterns in different ways at public and private institutions. Sample sizes for each subgroup of colleges are provided in Tables 1, 2, 3 along with descriptive statistics for variables included in our analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all institutions and states at start and end of study period: 2004 and 2012

| Public and private (N = 1212) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2012 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| College characteristics | ||||

| Percent of students whose parents are in the | ||||

| 1st income quintile | 8.2% | 6.6 | 8% | 6.0 |

| 2nd income quintile | 12.7% | 6.4 | 12% | 7.3 |

| 3rd income quintile | 18.4% | 5.6 | 17.3% | 5.5 |

| 4th income quintile | 25% | 6.6 | 25.1% | 7.1 |

| 5th income quintile | 35.7% | 16.7 | 37.6% | 17.4 |

| Number of students whose parents are in the | ||||

| 1st income quintile | 64 | 11.7 | 74 | 125.4 |

| 2nd income quintile | 101 | 165.2 | 112.8 | 187.9 |

| 3rd income quintile | 151 | 268.6 | 166 | 285.8 |

| 4th income quintile | 221 | 427.8 | 254 | 479.5 |

| 5th income quintile | 364 | 676.0 | 441 | 806.2 |

| % out-of-state enrollment | 32.8% | 25.2 | 34.4% | 25.5 |

| Tuition and fees | $17,682 | 9829.9 | $22,653 | 12,003.3 |

| Average amount of institutional aid | $8382 | 6050.8 | $11,757 | 8137.5 |

| Average amount of federal grant aid | $4234 | 1259.0 | $4860 | 689.9 |

| Average amount of state/local grant aid | $3556 | 2152.1 | $3553 | 2106.4 |

| State and local appropriations per FTE | $3031 | 5183.5 | $2369 | 4150.6 |

| % receiving institutional grant aid | 62.3% | 30.8 | 71.1% | 29.0 |

| % receiving state/local grant aid | 37.2% | 23.1 | 35.6% | 21.9 |

| % receiving federal grant aid | 27.7% | 13.4 | 35.3% | 14.4 |

| Number receiving Pell grant | 1745 | 2900.2 | 2766 | 5480.0 |

| State characteristics | ||||

| % of population with at least a bachelor’s degree | 18% | 4.0 | 19.8% | 4.7 |

| College-aged populationa | 200,745 | 219,886.8 | 284,244 | 318,350.7 |

| % of white, non-Hispanic in college-aged population | 76.3% | 18.0 | 71.8% | 16.8 |

| % of black, non-Hispanic in college-aged population | 12.4% | 13.8 | 13.1% | 12.3 |

| % of Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic in college-aged population | 3.4% | 7.9 | 3.3% | 5.9 |

| % of Hispanic of any race in college-aged population | 8% | 10.1 | 11.7% | 11.3 |

| Unemployment rate in civil labor force | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.09 | 0.0 |

| Per capita personal income | $41,127 | 6656.9 | $44,483 | 7845.6 |

| Percent of households owning a housing unit | 68% | 5.8 | 66.2% | 5.7 |

| Percent of households living in metropolitan areas | 69.5% | 20.5 | 73.8 | 18.3 |

aCollege-aged population is defined as population age 17–21 with at least a high school diploma

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for income quintile enrollments at the start and end of the study period by institutional type: 2004 and 2012

| Elite and highly selective | Selective | Non-selective | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public (N = 33) | Private (N = 144) | Public (N = 278) | Private (N = 528) | Public (N = 104) | Private (N = 125) | ||||||||

| 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | ||

| Percent of students whose parents are in the | |||||||||||||

| 1st income quintile | 5.4% (2.8) | 5.3% (2.3) | 3.7% (1.6) | 3.9% (1.7) | 9% (6.4) | 8.6% (5.7) | 7.3% (5.0) | 7.1% (5.0) | 14.8% (8.5) | 13.3% (7.2) | 15% (10.2) | 15.1% (9.3) | |

| 2nd income quintile | 8.5% (2.8) | 8.2% (3.1) | 6.2% (2.2) | 5.6% (2.1) | 13.3% (5.7) | 12.8% (6.7) | 12.5% (5.3) | 11.1% (5.6) | 19.6% (6.9) | 19.2% (8.4) | 18.5% (7.6) | 18.8% (9.2) | |

| 3rd income quintile | 13% (2.5) | 12.8% (3.3) | 10.6% (3.1) | 9.7% (2.9) | 18.9% (4.2) | 17.6% (4.1) | 19.3% (5.0) | 17.9% (5.0) | 22.9% (4.3) | 22.2% (3.5) | 20.6% (4.5) | 20.4% (4.6) | |

| 4th income quintile | 21.8% (4.5) | 20.8% (3.7) | 17.4% (4.7) | 17.2% (5.0) | 26.1% (5.1) | 25.9% (5.5) | 26.7 (5.9) | 27.3% (6.3) | 24.4% (6.9) | 25.1% (8.0) | 21.8% (7.3) | 21.6% (7.7) | |

| 5th income quintile | 51.3% (9.3) | 52.9% (8.9) | 62.2% (9.4) | 63.7% (9.0) | 32.7% (12.7) | 35.1% (14.0) | 34.1 (12.8) | 36.7% (13.7) | 18.2% (10.4) | 20.3% (10.9) | 24.1% (15.0) | 24.2% (15) | |

| Number of students whose parents are in the | |||||||||||||

| 1st income quintile | 230 (205.9) | 269 (242.8) | 29 (32.5) | 33 (35.6) | 138 (139.0) | 160 (181.4) | 24 (34.8) | 27 (35.7) | 109 (92.3) | 126 (114.0) | 68 (118.6) | 72 (123.5) | |

| 2nd income quintile | 386 (389.3) | 428 (418.7) | 47 (47.3) | 49 (50.3) | 218 (233.6) | 246 (269.5) | 40 (43.8) | 41 (45.2) | 153 (120.0) | 185 (147.8) | 77 (122.0) | 82 (127.4) | |

| 3nd income quintile | 611 (721.4) | 680 (752.8) | 78 (69.4) | 81 (73.4) | 328 (391.5) | 363 (409.8) | 61 (51.3) | 66 (58.7) | 190 (161.5) | 229 (185.3) | 77 (111.7) | 82 (118.2) | |

| 4th income quintile | 1034 (1366.1) | 1161 (1528.2) | 128 (107.0) | 139 (114.2) | 482 (585.4) | 560 (656.5) | 87 (73.4) | 104 (89.5) | 227 (233.0) | 280 (273.0) | 70 (85.4) | 77 (99.9) | |

| 5th income quintile | 2239 (1869.3) | 2652 (2247.3) | 492 (416.5) | 558 (464.8) | 690 (857.8) | 866 (1035.0) | 129 (153.0) | 163 (188.4) | 194 (237.1) | 255 (298.8) | 73 (86.2) | 80 (98.8) | |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for covariates at the start and end of the study period by institutional type: 2004 and 2012

| Elite and highly selective | Selective | Non-selective | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public (N = 33) | Private (N = 144) | Public (N = 278) | Private (N = 528) | Public (N = 104) | Private (N = 125) | |||||||

| 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | |

| % out-of-state enrollment | 16.9% (12.4) | 20.3% (11.5) | 67.2% (21.2) | 70% (20.1) | 15.7% (14.1) | 17.1% (15.4) | 38.3% (23.3) | 39.2% (23.0) | 15.9% (14.8) | 17.4% (15.5) | 37% (26.9) | 38.8% (26.7) |

| Tuition and fees | $9839 (2905.8) | $14,713 (4550.0) | $33,503 (4562.6) | $41,821 (4090.7) | $6991 (2659.0) | $9822 (3636.5) | $21,801 (5175.5) | $27,197 (6513.8) | $5836 (2029.2) | $7742 (2416.2) | $18,651 (5812.7) | $21,378 (7375.7) |

| Avg. amount of institutional aid | $5549 (2064.6) | $6905 (3300.7) | $19,540 (5800.2) | $26,705 (7398.8) | $3364 (1739.9) | $4529 (2239.1) | $9561 (3664.3) | $13,438 (4647.5) | $2802 (1644.4) | $3869 (1951.6) | $5252 (3241.0) | $7146 (4943.3) |

| Avg. amount of federal aid | $4108 (448.6) | $4757 (240.2) | $5457 (1366.2) | $5636 (1057.7) | $3808 (678.0) | $4670 (403.0) | $4267 (1392.8) | $4769 (653.3) | $3798 (674.9) | $4666 (524.9) | $4151 (1093.3) | $4574 (1039.7) |

| Avg. amount of state/local aid | $4051 (1303.9) | $5811 (3732.6) | $4356 (2609.2) | $3875 (2627.9) | $2786 (1241.4) | $3327 (1911.1) | $3901 (2285.4) | $3618 (1881.2) | $2345 (1538.8) | $2743 (1325.6) | $3799 (2067.4) | $3716 (2095.2) |

| State appropriations per FTE | $12,772 (5359.3) | $9886 (4978.6) | $160 (881.5) | $114 (786.6) | $8418 (4816.1) | $6569 (4399.8) | $52 (267.8) | $32 (224.5) | $8311 (6315.7) | $6588 (4047.2) | $51 (223.5) | $22 (154.8) |

| % receiving institutional aid | 34.1% (17.3) | 48.8% (18.0) | 64.2% (18.5) | 68.7% (19.6) | 31.5% (17.5) | 44% (21.1) | 84% (19.1) | 91.2% (16.1) | 29.4% (20.4) | 39.6% (22.5) | 59.4% (30.3) | 64.6% (31.5) |

| % receiving state/local aid | 41.5% (19.9) | 36.1% (22.3) | 17.9% (13.9) | 13.1% (12.4) | 37.8% (21.8) | 39.4% (22.4) | 38.9% (23.2) | 36% (20.3) | 35.2% (22.9) | 40.9% (19.1) | 42.7% (26.3) | 41% (25.7) |

| % receiving federal grant aid | 19.0% (7.1) | 26.5% (8.3) | 14.3% (5.1) | 18.3% (6.0) | 28.1% (12.0) | 36.9% (12.5) | 27.8% (11.0) | 34.7% (11.7) | 37.3% (13.2) | 45.1% (13.8) | 41.7% (18.5) | 47% (17.6) |

| Number receiving Pell grant | 6417 (6900.7) | 8519 (9840.4) | 584 (622.7) | 770 (790.2) | 3940 (4149.2) | 5824 (7130.4) | 1265 (5501.5) | 1567 (5641.7) | 2925 (2307.1) | 4379 (3683.0) | 3104 (8830.1) | 3389 (8968.1) |

We leveraged several large-scale data sources to construct a unique panel dataset through which we examined enrollment patterns by economic status in years leading up to and following the Great Recession. Data sources included (1) the National Center for Education Statistics’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS); (2) Peterson’s proprietary data on colleges’ admissions and financial aid practices and policies; (3) the U.S. Census Bureau’s demographic, occupational, educational attainment, and other community-level data; and (4) Opportunity Insight’s Mobility Report Card data, hereafter MRC data (opportunityinsights.org; see Chetty et al. 2017 for detailed documentation). MRC data represent the most detailed and comprehensive college-level information on economic backgrounds of students publicly available. The data identify the fraction of students by income quintile enrolled at sample colleges in the early 2000s using federal tax and Department of Education records from children born between 1980 and 1991 and their parents.

IPEDS identifies colleges by the six-digit Office of Postsecondary Education ID (OPEID) and MRC uses a super OPEID (which groups together some institutions that are identified separately by the six-digit identifier). We reconciled the two identifiers using an MRC-generated crosswalk, which required us to collapse IPEDS data from six-digit identifier to the super OPEID level. For variables with absolute numbers (e.g., number of students receiving institutional aid), we collapsed data by summing data from branch campuses; for variables with percent or average (e.g., average amount of institutional aid per student), we used the enrollment-weighted average of campuses in the cluster.

We also considered the potential impact of the parent–child reporting in IPEDS in which data for a branch campus is reported as part of the main campus data (Jaquette and Parra 2014). This causes inconsistency when merging IPEDS survey components because the parent–child relation often differs across survey components. For example, Pennsylvania State University campuses individually report enrollment data, while some branch campuses report finance data with the main campus. By collapsing data from different components to a higher level (super OPEID), we avoided most parent–child reporting issues. However, if separate super OPEIDs included institutions that reported data together in IPEDS (within a parent–child relationship), we combined the super OPEIDs.

Dependent Variables

Our outcome variables were the number of students enrolled at a given college by each income quintile in a given year.5 To generate these variables, we multiplied the fraction of students from each income quintile by birth cohort size, both available in MRC data. We logged enrollment outcomes to account for a non-normal distribution.

Independent Variables of Interest

To examine enrollment trends over time (RQ1), our independent variables of interest were year indicator variables, with 2004 serving as the referent year. Year indicator variables gave us a sense of how enrollment patterns changed over the period we examined, after adjusting for college- and state-level covariates described below.

To determine whether enrollment responses were more severe at colleges that experienced larger (or smaller) economic shocks during the recession (RQ2), we first created a continuous variable to capture state-level “recession intensity.” We calculated recession intensity for each state as the difference in log employment during the recessionary period (calendar years 2007–2009) and the state’s pre-recession trend (calendar years 2003–2005), relative to trends in aggregate national employment over the same period. This was a time-invariant indicator adapted from recent K-12 school district-level work examining how recession intensity shaped academic outcomes (Shores and Steinberg 2017; also see Yagan 2016). The state recession intensity variable was defined by the following equation:

| 1 |

where denotes the number of employed civilian non-institutional labor force in state s in calendar year t, and where denotes total employment across states in year t. A lower value of recession intensity (more negative) indicates that employment in a state was hit harder during the recession. To make interpretation of results more intuitive, we transformed recession intensity to 0—; after this transformation, states in which employment levels dropped the most relative to their pre-recession trends had higher (more positive) values of recession intensity.

To account for different geographical student markets in which colleges operate—for instance, highly selective institutions may draw students from a national market while less selective colleges may enroll primarily students from the surrounding area—we weighted the state-level recession intensity variable by the geographic distribution of each college’s student body prior to the recession using fall 2006 enrollment. That is, recession intensity for each college is calculated by multiplying the state-level recession intensity by the percent of students enrolled from each state in fall 2006 using the following equation:

| 2 |

where s = 1, 2, 3,…51 are 50 states and DC; is the enrollment of institution i coming from state s in fall 2006; and is the total enrollment of institution i in fall 2006.

This institution-level recession intensity variable is a measure of how severely the recession affected enrollees at a particular institution. Institutional recession intensity was larger (more severe) when a larger portion of an institution’s students came from areas harder hit by the recession.

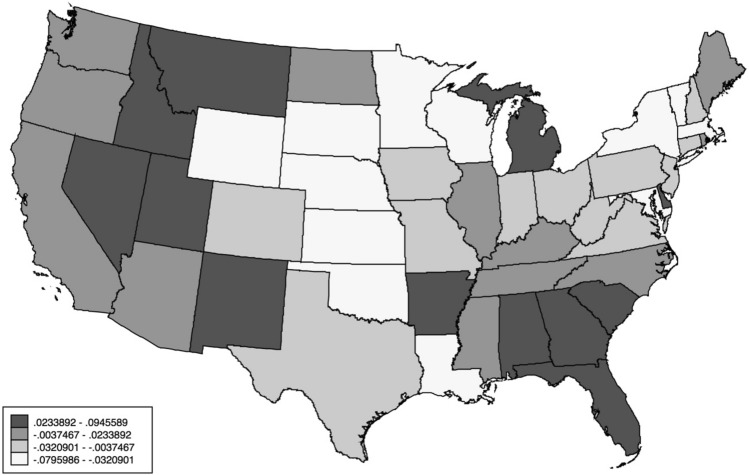

Finally, we interacted institutional recession intensity measures with a post-recession year indicator variable (equal to 1 for all years from 2009 to 2012)6 to examine whether enrollment changes in the wake of the Great Recession were more pronounced at campuses that enrolled a larger share of students from states affected more severely by the recession. Recession intensity by state is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Map of state recession intensity. State recession intensity is derived based on Eq. (1). State employment data are

taken from the local area unemployment statistics, available for download at the bureau of labor statistics here https://www.bls.gov/lau/ex14tables.htm

Covariates

To control for potential confounding variables that are likely to influence enrollment patterns, we included a series of state- and college-level covariates. State-level covariates captured labor market and broader economic conditions as well as demographic trends. They included the percent of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher, size of the college-aged population (defined as 17–21-year-olds with a high school diploma or higher), percent of college-aged population by race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic), unemployment rate, per capita personal income, percent of households owning a house, and percent of households in metropolitan areas. These covariates, particularly per capita personal income, were selected to capture the opportunity institutions have to enroll student bodies that reflect their local communities (see Hoxby and Turner 2019 for a more detailed discussion of the importance of these factors for enrollment patterns).

College-level covariates captured prices students at a particular college faced, characteristics of the student body, and financial resources available at a college. These included annual tuition and fees,7 average amount and percent of students receiving institutional aid, average amount and percent of students receiving state/local aid, average amount and percent of students receiving federal aid, number of students receiving the Pell grant, state and local appropriations per full-time equivalent student, and percent of students enrolled from out of state.8 Financial variables were adjusted to 2015 dollars using the Consumer Price Index and logged to account for non-normal distributions. Because our analysis draws on data from multiple sources over nearly a decade-long period, there were some cases of missing data in our sample. We excluded observations missing data on any outcome or covariate in a given year, resulting in 7% of total sample observations excluded from our analysis.

Table 1 provides a descriptive overview of variables included in our analysis at the beginning and end of the study period. The state-level characteristics provide context for state patterns during the period before the Great Recession and into the slow recovery that followed. As one would anticipate, the average state unemployment rate in the civilian labor force was 9% at the end of the study period, up from the beginning of the period. The percent of households owning a housing unit was down. The college-aged population reflects trends in American demographics: larger proportions of the college-aged population were Hispanic (of any race) and Black in the post-recession period. Individuals were more likely to live in urban/metropolitan areas in 2012 than in 2004. Incomes were higher at the end of the study period than at the beginning. At the college level, we find decreases in state and local appropriations per FTE during the study period, which goes hand in hand with an increase in tuition and drop in the percentage of students receiving state/local grant aid. Perhaps to fill these gaps, there was an increase in the average amount of institutional and federal grant aid students received while state/local grant aid stayed flat.

Patterns were more pronounced when disaggregated by institutional type. In Tables 2, 3 we observe that the share of enrollments of students from the bottom four quintiles decreased at public elite and highly selective institutions while enrollments of students from families in the top quintile increased between 2004 and 2012. Interestingly, similar trends emerged at public non-selective institutions. Even though these universities traditionally serve low-income students, we see proportions of students in the lower quintiles decreasing over the course of the study period, while students from the highest income quintiles increased the size of their public non-selective institutional pie.

Not only did proportions change, the average numbers of students from each economic quintile demonstrated similar patterns of stratification. Enrollment at elite and highly selective universities, both public and private, expanded during the period. We observe increases in all income quintiles; however, the largest gains came from the fourth and fifth quintiles—with the top quintile dwarfing all others (almost doubling the enrollment growth of all other quintiles combined).

Enrollments across all income quintiles also expanded at selective institutions over the period. While the top quintiles saw enrollment gains at selective public and private institutions, the fifth quintile again dwarfed all others. There were public versus private differences at non-selective institutions across the study period. At public non-selective institutions, all quintiles expanded enrollments evenly. Private non-selective institutions saw no change in enrollments among students in the bottom three quintiles while enrollments increased among students in the top quintile.

Analytic Strategy

We used fixed effects panel regression to examine enrollment patterns within each institutional type during the first decade of the 2000s (RQ1). The fixed effects model, in addition to controlling for a series of time-varying state- and college-level covariates, also allows us to control for unobserved time-invariant characteristics of sample colleges that are likely to shape enrollment patterns thus reducing potential bias from omitted variables. For instance, a college’s culture or history may make it more (or less) welcoming to low-income students. The fixed effects model for RQ1 can be expressed:

| 3 |

where represents the number of students from each income quintile; represents a vector of time-varying state-level covariates lagged by one year; represents a vector of time-varying college-level covariates; represents a series of year dummy variables that allow us to examine trends in enrollment over time and are the associated coefficients; represent college fixed effects; and is the error term. We estimated robust standard errors clustered at the college level, which are appropriate for panel data analyses with a large number of units (Wooldridge 2010).

For RQ2, which asks how the varying intensity of the recession shaped enrollment by institutional type, we estimated a second model, this time with the inclusion of our institutional recession intensity measure. The model can be expressed:

| 4 |

where represents the dependent variables; is an indicator for post-recession academic years(1 if year ≥ 2009; 0 if year ≤ 2008); is a college’s recession intensity. , is the coefficient for institutional recession intensity interacted with post-recession years, the primary independent variable of interest that tests whether colleges enrolling students from areas that experienced the recession experienced greater changes in enrollment in post-recession years.

Limitations

Our study describes enrollment patterns over the first decade of the 2000s and seeks to understand how the Great Recession influenced enrollment patterns among students from varied economic backgrounds by institutional type. We focus on four-year colleges and universities because our data provide better coverage of enrollments at institutions that primarily enroll students immediately or shortly after high school graduation. The MRC data link students to the college they attended at age 20, thus excluding a large percentage of community college students, 44 percent of whom are over age 25 (Ma and Baum 2016). Given the important role community colleges play in providing access to higher education for lower-income students, particularly during recession periods, this data limitation prevents us from examining the full scope of postsecondary enrollment patterns. Nonetheless, our study offers insight into how the recession shaped stratification patterns within the four-year college sector.

Additionally, while we control for a series of state- and college-level characteristics and time-invariant characteristics of colleges that are all likely to shape enrollment patterns, our aim is not to identify the causal impact of the recession on enrollments but rather to unveil relationships and trends. In light of this, we consider several alternate explanations or confounding factors that could shape the patterns we observed.

For instance, a number of federal policy efforts in the early 2000s that focused on college access and affordability also likely influenced college enrollment patterns. In reauthorizing the Higher Education Act in 2008, Congress greatly expanded the Pell Grant program, which is directed toward low-income students but also extends to some middle-income families (Delisle 2017; Rosinger and Ford 2019). Between 2008 and 2009, spending on Pell rose from $20 to $33.5 billion and the number of students receiving Pell grew from 6.2 to more than 8 million (College Board 2017). We control for the number of students receiving Pell indicating the changes in enrollment patterns we observed are independent of broader policy changes in the Pell program; however, changes in the composition of students receiving federal grant aid could surreptitiously influence our estimates. Similarly, broader economic or demographic trends could also influence college enrollment. We control for many of these factors—unemployment rate, per capita personal income—as well as demographic trends, particularly among the college-aged population. However, unobservable factors in the economy, such as labor market discrimination, could also drive enrollment patterns.

Finally, there are two factors that simultaneously shape enrollment patterns that existing data do not allow researchers to distinguish between. Namely, enrollment is shaped by supply and demand side factors: colleges and universities supply spots for students and may expand or limit enrollments in response to financial or other pressures while at the same time student demand for higher education and for particular higher education institutions is shaped by labor market conditions, perceptions of price and quality, and other factors. We observe actual student enrollments rather than the specific supply and demand conditions contributing to these enrollments. In interpreting our findings, we place an emphasis on colleges’ role in shaping enrollment patterns because institutions, particularly selective institutions, play a large role in recruiting, selecting, and encouraging students to enroll—rather than on student behavior, which in many ways is responsive to college behaviors. For instance, recent research reveals how selective colleges’ recruiting practices that focus on white, wealthy, out-of-state high schools likely contribute to observed stratification patterns (Han et al. 2019; Jaquette and Salazar 2018). However, it is important to highlight that students’ college decisions are not entirely dependent on the actions of institutions.

Findings

Over our study period, we found enrollment patterns stratified by family income quintile and institutional type. To examine how years leading up to and following the Great Recession shaped higher education enrollments for students from differing income background by institutional types (RQ1), we regressed logged enrollment for each income quintile on year by institutional type, controlling for time-varying state and college characteristics and time-invariant college fixed effects. Figure 2 plots the coefficients for each year from these models, showing how the pre- and post-recession period shaped enrollment patterns in each income quintile (in reference to 2004, the first year we observed). The first panel in Fig. 2 presents results for elite and highly selective colleges, the second panel for selective colleges, and the final panel for non-selective colleges.

Fig. 2.

Enrollment trends by income quintile and institutional selectivity. This figure plots the coefficients of year dummies in Eq. (3) separately estimated for all 4-year institutions by family income quintile and institutional selectivity. Control variables include college-level characteristics (tuition and fees, average amount and percent of students receiving institutional aid, average amount and percent of students receiving state/local aid, average amount and percent of students receiving federal aid, state and local appropriations per full-time equivalent student, and percent of students enrolled from out of state) and state-level characteristics (percent of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher, size of the college-aged population, percent of college-aged population by race, unemployment rate, per capita personal income, percent of households owning a house, and percent of households in metropolitan areas). Robust standard errors clustered at the college level are estimated. Dots in different shades of black represent significance levels of the coefficients

Interestingly, the early years of our analysis were associated with similar enrollment patterns for all quintiles, but later years saw a divergence, particularly coinciding with the onset of the recession in 2009, at the most selective institutional types (those categorized as elite and highly selective and selective institutions), recession and post-recession years were associated with a decline in enrollment among students in the second and third income quintiles and an increase in enrollment among students in the bottom and, particularly, the top two quintiles relative to 2004 levels. In many ways, enrollment patterns were similar at selective institutions. High-income students, those from families in the fourth and fifth quintiles, enrolled in selective institutions in increasing numbers across the period. Conversely, enrollment among students from the bottom three income quintiles declined across the period. These enrollment changes grew more pronounced in recession and post-recession years. Enrollment patterns over this period were less clear at non-selective institutions, with each income quintile experiencing gains and losses over time.

We next turn to examine how varying recession intensity shaped enrollment patterns by institutional type for students from differing income backgrounds (RQ2). In these models, we included institutional recession intensity interacted with an indicator variable for post-recession years (2009–2012) to investigate whether stratification worsened in areas where the economic shock of the recession was greatest. Table 4 presents findings from this analysis.

Table 4.

Coefficients of the interaction between recession intensity and post-recession period

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All institutions | |||||

| All institutions (N = 1212) | − 0.21 (0.27) | 0.74** (0.23) | 0.58** (0.22) | 0.35+ (0.20) | 0.11 (0.26) |

| All elite and highly selective (N = 177) | 0.38 (1.08) | 0.12 (0.73) | 0.77 (0.66) | 0.50 (0.60) | − 0.11 (0.70) |

| All selective (N = 806) | − 0.54+ (0.33) | 0.80** (0.26) | 0.65** (0.24) | 0.48* (0.22) | 0.16 (0.29) |

| All non-selective (N = 229) | 0.30 (0.53) | 0.49 (0.53) | 0.43 (0.51) | 0.03 (0.46) | 0.37 (0.60) |

| Public | |||||

| All public institutions (N = 415) | − 0.11 (0.32) | 0.24 (0.28) | 0.24 (0.26) | 0.29 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.33) |

| Public elite and highly selective (N = 33) | − 1.40 (1.36) | − 0.14 (1.10) | − 0.36 (0.84) | − 0.45 (0.88) | − 0.77 (1.09) |

| Public selective (N = 278) | − 0.30 (0.32) | 0.36 (0.29) | 0.36 (0.29) | 0.28 (0.28) | 0.16 (0.39) |

| Public non-selective (N = 104) | 0.44 (0.70) | 0.07 (0.70) | − 0.21 (0.59) | 0.02 (0.59) | 0.74 (0.64) |

| Private | |||||

| All private institutions (N = 797) | − 0.19 (0.43) | 1.15** (0.35) | 0.89** (0.34) | 0.50+ (0.29) | − 0.03 (0.38) |

| Private elite and highly selective (N = 144) | 0.60 (1.32) | − 0.59 (1.11) | 0.82 (0.89) | 0.32 (0.70) | − 0.11 (0.87) |

| Private selective (N = 528) | − 0.60 (0.54) | 1.05* (0.42) | 0.86* (0.38) | 0.84* (0.34) | 0.36 (0.42) |

| Private non-selective (N = 125) | 0.20 (0.75) | 1.58* (0.68) | 1.06 (0.84) | − 0.03 (0.75) | − 0.31 (0.99) |

Each cell represents the coefficient of from a regression based on Eq. (4). Control variables include college-level characteristics (tuition and fees, average amount and percent of students receiving institutional aid, average amount and percent of students receiving state/local aid, average amount and percent of students receiving federal aid, state and local appropriations per full-time equivalent student, percent of students enrolled from out of state, and log of number of students receiving Pell grant) and state-level characteristics (percent of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher, size of the college-aged population, percent of college-aged population by race, unemployment rate, per capita personal income, percent of households owning a house, and percent of households in metropolitan areas). Robust standard errors clustered

Findings indicate that at sample institutions where the recession was most intense, the middle-income quintiles made enrollment gains. When we examined this finding by institutional type, we found this trend primarily occurred at private selective colleges (for students in the middle three income quintiles) and non-selective colleges (for students in the second quintile), with no significant changes at elite/highly selective private institutions. Recession intensity did not have a statistically significant relationship with enrollment among students from families in the top or bottom income quintiles, indicating students from families in the top and bottom of the earnings distribution neither gained nor lost ground in places where the recession was most intense.

To understand whether the patterns we found differed over the post-recession recovery period, we also estimated models in which we interacted the recession intensity variable with a dummy variable for each post-recession year (2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012). This allowed us to examine whether there were lagged enrollment responses or whether our initial grouping of “post-recession period” masked different enrollment responses in the years immediately after the recession versus further into the recovery period. Findings from this analysis (presented in “Appendix” section) reveal similar patterns as the prior analysis: in places where the recession was most intense, enrollment gains occurred among students from the middle classes, primarily at selective private colleges. These gains, however, were somewhat lagged, primarily occurring in 2011 and 2012, perhaps indicating the recovery period proved particularly important in shaping college enrollment patterns for the middle classes.

Discussion

Prior research indicates enrollments were highly stratified by economic class and institutional type before the recession (Astin and Oseguera 2004; Bastedo and Jaquette 2011; Ford and Thompson 2016; Hearn and Rosinger 2014; Posselt et al. 2012; Roksa et al. 2007). This study draws on new data on the economic composition of colleges and universities to examine stratification in years leading up to and immediately following the Great Recession and how variations across states in recession intensity contributed (or did not) to stratified patterns.

Between 2004 and 2012, particularly in elite and selective institutions, enrollment gains occurred among students from families in the top income quintiles. One might imagine either or both the supply and demand sides explaining this trend. On the demand side, high-income families sought to secure and consolidate their advantages by selecting higher educational options that were prestigious, elite, and distinct in a marketplace where access to higher education was becoming more common. Seeking qualitatively better educational options among the same quantitative level of schooling is the central tenant of Effectively Maintained Inequality (Lucas 2001). On the supply side, universities may have tried to recruit and enroll higher-income students as a way to generate revenue through tuition in the face of declining state funds and endowment returns.

Because our study period spans years before, during, and after the Great Recession, it would be tempting to use a Disaster Capitalism framework and attribute the persistence and exacerbation of educational stratification we observed in our descriptive analysis to the shock of economic hardship caused by the recession. However, for a Disaster Capitalism framework to hold, the intensity of the stratified enrollments would follow the intensity of the economic shock. That is, we would expect to see the most class-stratified enrollment changes at institutions that enroll students from locales where the effects of the recession were most severe. Because we see stratified enrollments across the system, regardless of an institution’s recession intensity, we conclude that EMI is a better framework for describing the patterns observed during this period. We observe families from the top economic quintiles seeking qualitatively excellent educational opportunities for their children, no matter the costs, long before and throughout the recession years. Conversely, the longstanding marginalization from four-year college-going that existed for the bottom quintiles before the recession also continued.

In places where the recession was most intense, the expected exacerbation of economic stratification of enrollment patterns did not emerge. Rather, students from families in the middle quintiles increased enrollment at selective (though not the most selective) private universities. We suspect this middle-class enrollment expansion reflects the Pell expansion that occurred over this time period. Middle-class students increasingly qualify for Pell (Delisle 2017) and may have been able to use extra support from Pell to capitalize on the opportunity to attend higher-priced selective private colleges. Other policies that were in place during this period may have also served to support middle-class enrollments. Prior research indicates that the duration of unemployment benefits during the recession period led to increased postsecondary enrollments among recipients, particularly in the two-year college sector (Barr and Turner 2015). College financial aid policies could have also helped support middle-class enrollments. For example, prior research has shown that no-loan programs that replace loans with grant aid have boosted enrollment among upper-middle class students at selective private colleges (Rosinger et al. 2019). Middle-class students who were on the margin of attending college or attending a higher-priced institution were then financially able to do so due to Pell expansion and other policies. While these supports would have been available for lower-income families, it may not have been enough to dramatically change college decisions for families in the lowest income quintile. Student-level data would allow for a more detailed exploration of the factors driving middle-class enrollments during this time period.

The intensity of the recession did not appear to shape enrollment patterns for the top and bottom quintiles to the same extent as it did for middle-class families. We imagine that because of their extreme economic positions in society, the recession did not factor into their college enrollment behavior to the same extent as it did for middle-class families. For example, the top quintile, due to their extreme incomes, were buffered from the recession and expanded their enrollment share in elite colleges during the economic downturn. Conversely, for many families in the bottom income quintile, four-year college attendance was already uncommon before the recession, so we observe little change in enrollment due to the downturn in economic conditions. The cost of college attendance, which goes beyond tuition and housing, and includes foregone income, may be too expensive for this group (Goldrick-Rab 2016).

The expansion of enrollment among students from middle-class families may reflect the expansion of the federal Pell grant meant to buffer the effects of the recession during this time period. Middle-income students have received the Pell grant in larger numbers over time (Delisle 2017). Research also indicates that states have largely maintained their commitments to student financial aid during recessionary periods (Bettinger and Williams 2013), although increasing shares of state aid is awarded based on academic merit, which tends to disproportionately benefit middle- and upper-middle income students (Baker et al. 2020). Other state funding policies, such as appropriations to public colleges and universities, could similarly shape the enrollment patterns we observe among middle-income students. States have increasingly turned to performance-based funding—tying a portion of state funds to student outcomes—as a strategy to improve graduation rates and meet workforce goals (Kelchen 2018). Research indicates these policies have decreased access among lower-income students at selective public four-year colleges as these institutions seek to enroll students who are more likely to graduate (Gándara and Rutherford 2018; Umbricht et al. 2017). It is possible that the increasing trend toward performance funding at the state level led institutions to expand enrollment among middle-income students, while limiting enrollment opportunities for lower-income students. These federal and state policy choices, among others, may have supported enrollment among students from middle-class families during the first decade of the 2000s. Further analyses into the factors that supported middle-class students during this period would inform federal and state policymakers and higher education leaders regarding how to support students during recessionary periods.

These findings offer some insight into what future economic recessions may bring for higher education enrollments. As the country experiences another economic downturn brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the implications of economic shocks on enrollment patterns becomes increasingly important.9 While the causes and consequences of every economic shock are different, our findings indicate that, at the very least, we might expect existing educational inequalities to continue in the coming years. However, we also caution that a looming economic recession after a recovery from the last downturn in which the lowest income families saw few gains and higher education institutions have yet to reach pre-Great Recession state funding levels could widen enrollment gaps by family income. Early analyses of the current economic downturn point to an uneven recession, with low-income and racially minoritized families being hardest hit. These same families face a dual burden of a recession coupled with a virus: economic and social conditions these groups face place them at higher risk of illness and death from the disease (Adhikari et al. 2020; National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases 2020). These troubling trends point to potentially more pronounced effects on enrollment in the coming years.

Appendix

See Table 5.

Table 5.

Coefficients of recession intensity by year

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All institutions | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.40 (0.32) | 0.26 (0.24) | 0.46* (0.22) | 0.03 (0.20) | 0.06 (0.29) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.28 (0.35) | 0.82** (0.30) | 0.41 (0.27) | 0.47+ (0.25) | 0.34 (0.31) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.11 (0.38) | 1.26** (0.33) | 0.66* (0.30) | 0.61* (0.26) | 0.12 (0.32) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.08 (0.37) | 0.95** (0.32) | 0.92** (0.30) | 0.48+ (0.27) | − 0.08 (0.34) |

| All elite and highly selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | 0.08 (1.17) | 1.43+ (0.80) | 0.44 (0.67) | 0.08 (0.57) | 0.19 (0.58) |

| Intensity × year 10 | 0.55 (1.34) | 0.31 (0.99) | 0.93 (0.81) | 1.08 (0.89) | − 0.15 (0.77) |

| Intensity × year 11 | 0.30 (1.68) | − 0.71 (1.19) | 0.85 (1.19) | 0.29 (0.71) | − 0.28 (0.94) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.90 (1.53) | − 2.12+ (1.11) | 1.15 (1.26) | 0.86 (0.78) | − 0.50 (0.93) |

| All selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.72+ (0.39) | 0.16 (0.29) | 0.51* (0.26) | 0.09 (0.22) | 0.07 (0.26) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.53 (0.44) | 0.75* (0.35) | 0.44 (0.30) | 0.50+ (0.29) | 0.33 (0.36) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.49 (0.45) | 1.43** (0.38) | 0.75* (0.31) | 0.81** (0.30) | 0.16 (0.38) |

| Intensity × year 12 | − 0.29 (0.44) | 1.33** (0.35) | 1.06** (0.33) | 0.80** (0.30) | 0.11 (0.38) |

| All non-selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | 0.37 (0.65) | 0.04 (0.54) | 0.49 (0.48) | − 0.04 (0.49) | 0.23 (0.97) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.13 (0.64) | 0.89 (0.67) | 0.22 (0.67) | 0.29 (0.62) | 0.89 (0.72) |

| Intensity × year 11 | 0.43 (0.73) | 0.93 (0.70) | 0.45 (0.74) | 0.29 (0.58) | 0.44 (0.66) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.54 (0.81) | 0.30 (0.82) | 0.57 (0.71) | − 0.42 (0.67) | − 0.07 (0.81) |

| All public institutions | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.29 (0.33) | 0.06 (0.29) | 0.02 (0.26) | 0.17 (0.25) | 0.47 (0.32) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.09 (0.39) | 0.21 (0.32) | 0.02 (0.31) | 0.36 (0.30) | 0.79* (0.37) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.30 (0.44) | 0.47 (0.39) | 0.34 (0.32) | 0.43 (0.31) | 0.07 (0.41) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.35 (0.42) | 0.29 (0.38) | 0.68* (0.34) | 0.24 (0.34) | − 0.03 (0.44) |

| Public elite and highly selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.59 (0.98) | 0.78 (0.79) | − 1.02 (1.19) | − 0.48 (0.83) | − 0.47 (0.75) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 3.10+ (1.69) | − 0.15 (1.37) | − 0.20 (1.00) | − 0.09 (1.34) | − 1.13 (1.23) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 1.40 (2.73) | − 1.70 (2.18) | 0.48 (1.89) | − 1.05 (0.89) | − 0.87 (1.66) |

| Intensity × year 12 | − 0.72 (2.29) | − 1.80 (1.13) | 0.79 (2.06) | − 0.44 (1.14) | − 1.00 (1.72) |

| Public selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.64+ (0.33) | − 0.20 (0.28) | 0.02 (0.29) | 0.09 (0.25) | 0.30 (0.33) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.17 (0.46) | 0.38 (0.36) | 0.16 (0.36) | 0.25 (0.34) | 0.59 (0.44) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.36 (0.49) | 0.76+ (0.41) | 0.51 (0.33) | 0.51 (0.36) | 0.02 (0.49) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.14 (0.43) | 0.81* (0.39) | 0.91* (0.36) | 0.39 (0.34) | − 0.36 (0.46) |

| Public non-selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | 0.77 (0.78) | 0.59 (0.73) | 0.13 (0.63) | 0.22 (0.65) | 0.69 (0.77) |

| Intensity × year 10 | 0.59 (0.75) | − 0.09 (0.79) | − 0.47 (0.73) | 0.22 (0.65) | 1.46+ (0.74) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.29 (0.86) | 0.27 (0.90) | − 0.36 (0.74) | 0.12 (0.65) | 0.04 (0.75) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.61 (1.01) | − 0.73 (1.05) | − 0.22 (0.81) | − 0.64 (0.96) | 0.78 (1.16) |

| All private institutions | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.38 (0.54) | 0.37 (0.39) | 0.82* (0.33) | 0.06 (0.29) | − 0.12 (0.49) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.36 (0.57) | 1.26* (0.50) | 0.70 (0.43) | 0.63 (0.40) | 0.05 (0.48) |

| Intensity × year 11 | 0.12 (0.60) | 1.95** (0.51) | 0.95+ (0.48) | 0.81+ (0.41) | 0.12 (0.47) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.04 (0.61) | 1.63** (0.49) | 1.19* (0.49) | 0.83+ (0.43) | − 0.13 (0.49) |

| Private elite and highly selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | 0.15 (1.91) | 1.48 (1.39) | 0.98 (0.98) | − 0.42 (0.78) | 0.23 (0.88) |

| Intensity × year 10 | 2.01 (1.88) | − 1.01 (1.39) | 0.71 (1.07) | 0.83 (0.96) | − 0.03 (1.00) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.24 (1.71) | − 1.14 (1.57) | 0.38 (1.35) | 0.23 (1.03) | − 0.44 (1.11) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.58 (1.84) | − 3.35+ (1.92) | 1.08 (1.47) | 1.15 (0.99) | − 0.50 (1.05) |

| Private selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.58 (0.68) | 0.36 (0.48) | 0.81* (0.41) | 0.30 (0.34) | 0.14 (0.39) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.77 (0.72) | 0.82 (0.60) | 0.63 (0.47) | 0.81+ (0.45) | 0.35 (0.55) |

| Intensity × year 11 | − 0.49 (0.75) | 1.84** (0.63) | 0.89+ (0.51) | 1.21* (0.47) | 0.39 (0.57) |

| Intensity × year 12 | − 0.53 (0.76) | 1.79** (0.56) | 1.20* (0.55) | 1.49** (0.49) | 0.77 (0.61) |

| Private non-selective | |||||

| Intensity × year 09 | − 0.06 (0.95) | 0.10 (0.73) | 0.91 (0.72) | − 0.24 (0.73) | − 0.33 (1.64) |

| Intensity × year 10 | − 0.49 (0.98) | 2.62** (0.95) | 0.87 (1.13) | 0.16 (1.07) | − 0.03 (1.18) |

| Intensity × year 11 | 1.25 (1.17) | 2.66** (0.89) | 1.37 (1.32) | 0.46 (1.06) | 0.50 (1.13) |

| Intensity × year 12 | 0.66 (1.21) | 2.36* (1.10) | 1.30 (1.21) | − 0.33 (1.04) | − 1.42 (1.06) |

Control variables include college-level characteristics (tuition and fees, average amount and percent of students receiving institutional aid, average amount and percent of students receiving state/local aid, average amount and percent of students receiving federal aid, state and local appropriations per full-time equivalent student, percent of students enrolled from out of state, and log of number of students receiving Pell grant) and state-level characteristics (percent of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher, size of the college-aged population, percent of college-aged population by race, unemployment rate, per capita personal income, percent of households owning a house, and percent of households in metropolitan areas). Robust standard errors clustered at the college level in parentheses

**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Research estimating the returns to attending a selective college has produced mixed results, with some pointing toward positive impacts on future earnings (e.g., Mayhew et al. 2016; Witteveen and Attewell 2017; Zhang 2012) and others demonstrating little effect, except for traditionally underrepresented populations at elite colleges such as low-income, minority, and first-generation students (e.g., Dale and Krueger 2002, 2014).

In its earliest conceptual forms, Disaster Capitalism identified the mechanism through which inequality was exacerbated by a shock: neoliberal, self-interested organizations and actors seeking to profit in the chaos created by a disaster. As the theory has gained wider use, it now describes the patterns of exacerbated inequality after a shock broadly, without necessarily specifying the mechanisms. For the purposes of this paper, we employ Disaster Capitalism in this broad sense and do not make claims about self-interested neoliberal institutions driving the patterns we discuss.

There is little reason to think there would be less stratification or more equitable distribution of students as a result of an economic downturn, so our analysis will examine if stratification worsened or remained the same.

We excluded institutions that were not ranked in the Barron’s index.

The Opportunity Insights data links students to the college they attended at age 20 (Chetty et al., 2017).

Year is defined as end of the academic year: 2009 represents data from the 2008–2009 academic year.

Tuition and fees is the average of in-state and out-of-state tuition and fees weighted by percent in-state and out-of-state enrollment.

Out-of-state enrollment (reported as number of students by state of residence) was not reported in IPEDS in odd years, so we imputed enrollment in odd years by taking the average of t − 1 and t + 1. For example, state of residence was reported in 2004 and 2006 but not 2005. We used the average number of students by state of residence between 2004 and 2006 to impute information for 2005.

We note that the uneven recovery from the Great Recession means that some families had not recovered when the 2020 recession began. We also note that these two recessions have substantive differences in their causes (manufactured by the financial sector versus a natural disaster) and therefore will have many differences in their effects and severity.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aalbers MB. The great moderation, the great excess and the global housing crisis. International Journal of Housing Policy. 2015;15(1):43–60. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2014.997431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari S, Pantaleo NP, Feldman JM, Ogedegbe O, Thorpe L, Troxel AB. Assessment of community-level disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections and deaths in large US metropolitan areas. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7):e2016938–e2016938. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astin AW, Oseguera L. The declining “equity” of American higher education. Review of Higher Education. 2004;27(3):321–341. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2004.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D., Rosinger, K., Ortagus, J., & Kelchen, R. (2020). Trends in state funding for student financial aid. InformEd States.

- Barr A, Turner S. Out of work and into school: Labor market policies and college enrollment during the Great Recession. Journal of Public Economics. 2015;124:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr A, Turner SE. Expanding enrollments and contracting state budgets: The effect of the Great Recession on higher education. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2013;650(1):168–193. doi: 10.1177/0002716213500035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron’s . Barron’s profiles of American colleges. 25. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bastedo MN, Jaquette O. Running in place: Low-income students and the dynamics of higher education stratification. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2011;33(3):318–339. doi: 10.3102/0162373711406718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger E, Williams B. Federal and state financial aid during the great recession. In: Brown J, Hoxby C, editors. How the financial crisis and great recession affected higher education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2013. pp. 235–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, Lovenheim MF, Turner S. Why have college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resources. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2(3):129–157. doi: 10.1257/app.2.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board C. Trends in student aid. New York: College Board; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America's public universities. Princeton University Press.

- Brown JR, Dimmock SG, Kang JK, Weisbenner SJ. How university endowments respond to financial market shocks: Evidence and implications. American Economic Review. 2014;104(3):931–962. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.3.931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale AP, Rose S. Socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and selective college admissions. New York, NY: The Century Foundation Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale AP, Strohl J. Separate and unequal: How higher education reinforces the intergenerational reproduction of white racial privilege. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Friedman J, Saez E, Turner N, Yagan D. Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dale SB, Krueger AB. Estimating the payoff to attending a more selective college: An application of selection on observables and unobservables. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2002;117(4):1491–1527. doi: 10.1162/003355302320935089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SB, Krueger AB. Estimating the effects of college characteristics over the career using administrative earnings data. Journal of Human Resources. 2014;49(2):323–358. doi: 10.1353/jhr.2014.0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle J. The Pell Grant proxy: A ubiquitous but flawed measure of low-income student enrollment. Seattle: Semantic Scholar; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass JA. Higher education budgets and the global recession: Tracking varied national responses and their consequences. Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education, University of California; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar A, Hossler D, Shapiro D, Chen J, Martin S, Torres V, Zerquera D, Ziskin M. National postsecondary enrollment trends before, during, and after the Great Recession. Washington, DC: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elsby MWL, Hobijn B, Sahin A. The labor market in the Great Recession (No. w15979) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, C. (2020). Frozen searches. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/01/scores-colleges-announce-faculty-hiring-freezes-response-coronavirus. Accessed 1April 2020.

- Ford KS, Thompson J. Inherited prestige: Intergenerational access to selective universities in the United States. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2016;46:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2016.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis SM. Discrimination in the credential society: An audit study of race and college selectivity in the labor market. Social Forces. 2014;93(4):1451–1479. doi: 10.1093/sf/sou111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gándara D, Rutherford A. Mitigating unintended impacts? The effects of premiums for underserved populations in performance-funding policies for higher education. Research in Higher Education. 2018;59(6):681–703. doi: 10.1007/s11162-017-9483-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber TP, Cheung SY. Horizontal stratification in postsecondary education: Forms, explanations, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:299–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzmann WN, Oster S. Competition among university endowments. In: Brown J, Hoxby C, editors. How the financial crisis and great recession affected higher education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2014. pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Goldrick-Rab S. Paying the price: College costs, financial aid, and the betrayal of the American dream. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Jaquette O, Salazar K. Recruiting the out-of-state university: Off-campus recruiting by public research universities. Chicago: The Joyce Foundation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J, Rosen C, Williams MR. Missouri Gov. Parson cutting $180 million from budget. Colleges taking biggest hit. Kansas: The Kansas City Star; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn JC, Rosinger KO. Socioeconomic diversity in selective private colleges: An organizational analysis. Review of Higher Education. 2014;38(1):71–104. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2014.0043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendey L, McKernan S, Woo B. Weathering the recession: The financial crisis and family wealth changes in low-income neighborhoods. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hooren FV, Kaasch A, Starke P. The shock routine: Economic crisis and the nature of social policy responses. Journal of European Public Policy. 2014;21(4):605–623. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.887757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hout M. Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;38:379–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoxby CM. The changing selectivity of American colleges. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2009;23(4):95–118. doi: 10.1257/jep.23.4.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoxby CM, Turner S. Measuring opportunity in U.S. higher education (No. w25479) Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes H, Miller DL, Schaller J. Who suffers during recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2012;26(3):27–48. doi: 10.1257/jep.26.3.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquette O, Curs BR. Creating the out-of-state university: Do public universities increase nonresident freshman enrollment in response to declining state appropriations? Research in Higher Education. 2015;56(6):535–565. doi: 10.1007/s11162-015-9362-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquette O, Curs BR, Posselt JR. Tuition rich, mission poor: Nonresident enrollment growth and the socioeconomic and racial composition of public research universities. The Journal of Higher Education. 2016;87(5):635–673. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2016.0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquette O, Parra EE. Using IPEDS for panel analyses: Core concepts, data challenges, and empirical applications. In: Paulsen M, editor. Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. pp. 467–533. [Google Scholar]

- Jaquette O, Salazar K. Colleges recruit at richer, whiter high schools. New York: New York Times; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kelchen R. Higher education accountability. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. Macmillan.

- Klugman J. The advanced placement arms race and the reproduction of educational inequality. Teachers College Record. 2013;115(5):1–34. [Google Scholar]