Abstract

Objective

To describe geographic variation in neurologist density, neurologic conditions, and neurologist involvement in neurologic care.

Methods

We used 20% 2015 Medicare data to summarize variation by Hospital Referral Region (HRR). Neurologic care was defined as office-based evaluation/management visits with a primary diagnosis of a neurologic condition.

Results

Mean density of neurologists varied nearly 4-fold from the lowest to the highest density quintile (9.7 [95% confidence interval (CI) 9.2–10.2] vs 43.1 [95% CI 37.6–48.5] per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries). The mean prevalence of patients with neurologic conditions did not substantially differ across neurologist density quintile regions (293 vs 311 per 1,000 beneficiaries in the lowest vs highest quintiles, respectively). Of patients with a neurologic condition, 23.5% were seen by a neurologist, ranging from 20.6% in the lowest quintile regions to 27.0% in the highest quintile regions (6.4% absolute difference). Most of the difference comprised dementia, pain, and stroke conditions seen by neurologists. In contrast, very little of the difference comprised Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis, both of which had a very high proportion (>80%) of neurologist involvement even in the lowest quintile regions.

Conclusions

The supply of neurologists varies substantially by region, but the prevalence of neurologic conditions does not. As neurologist supply increases, access to neurologist care for certain neurologic conditions (dementia, pain, and stroke) increases much more than for others (Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis). These data provide insight for policy makers when considering strategies in matching the demand for neurologic care with the appropriate supply of neurologists.

Neurologists comprise about 2% of physicians in the United States, which has been stable for the past decade.1,2 The prevalence of neurologic disorders has increased over time.3,4 As the population ages, the demand for neurologic care is projected to increase further.5

Geographic variability in neurologist supply may influence whether or not a neurologist is involved in the care of a patient with a neurologic disorder or symptom.5 However, regional variability in neurologists and whether this variability is associated with neurologist involvement in care has not been evaluated in detail. Prior research about geographic variation in neurologists was limited to the state level, which obscures important variation within states and the inclusion of a limited number of neurologic disorders.5,6

In this study, we used a population-based administrative dataset to examine the geographic variation in neurologist care at the level of Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs), which are regional health care markets for tertiary medical care. In addition, we aimed to determine the prevalence of neurologic conditions most commonly seen in practice across HRRs and the proportion of patients with these neurologic conditions who are seen by neurologists. Our objective was to provide data to inform ongoing discussions about matching the demand for neurologic care with the appropriate supply of neurologists.

Methods

Overview

We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of neurologic care in the United States using Medicare data. We had 3 specific goals: (1) to understand the geographic distribution of neurologists; (2) to measure the prevalence of neurologic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries across HRRs; and (3) to measure the proportion of Medicare patients with neurologic conditions who are seen by neurologists across HRRs.

Dataset

We used a random 20% selected national sample of the 2015 Fee-for-Service (FFS) Medicare Carrier file. Medicare 20% sample refers to 20% of patients/claims, not to the providers. This file includes claims from beneficiaries aged 65 years and older as well as beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or disability regardless of age. It contains data on medical services (diagnosis codes and procedures) and performing provider information (provider's identifier, specialty, and practice location). In addition, we obtained information regarding beneficiary demographics (age, sex) and residence from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF).

Study Population

We selected Medicare-insured adult patients with at least 1 office visit for a neurologic condition in 2015. We excluded patients residing outside the United States or with missing residence information (n = 2,118 patients), and excluded office visits with missing provider information (n = 24 office visit claims), or provided by physicians who were miscoded with organization National Provider Identifier (n = 24,568 office visit claims) or with missing practice location information (n = 75 office visit claims). The region where a patient resided was determined by the mailing address zip code in the MBSF, which was then assigned to the corresponding HRR. HRRs, defined by Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care,7 are 306 geographic areas covering 1 or more zip codes where medical resources are distributed and are thought to reflect tertiary referral patterns. Neurologist's practice location was determined by “carrier line performing provider zip code” in the Medicare Carrier files and assigned a corresponding HRR. The HRR was the unit of analysis.

Identification of Neurologists

Neurologists were defined by provider specialty code (13: neurology) in the Medicare Carrier files or health care provider taxonomy codes (2084N0600X, 2084A2900X, 2084N0400X, 2084N0008X, or 2084V0102X) in the National Provider Identifier files and who provided at least one office-based evaluation and management (E/M) service to Medicare patients in 2015. Office visits for E/M service were identified through the Current Procedural Terminology codes 99201–99205, 99241–99245, 99211–99215.

Identifying Neurologic Care

Neurologic care was defined as E/M visits with a primary diagnosis of a neurologic condition. Neurologic conditions were identified through ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes and classified using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) categories of the ICD with some modification by the authors to reflect disease categories among neurologic subspecialties.8 We selected the most common CCS categories seen by neurologists as the neurologic conditions to include in this study because visits for these conditions represented 85% of all E/M visits to the neurologists in 2015 (table 1).

Table 1.

Neurologic Condition Categories and Top 3 Diagnoses in Each Category

Outcomes

The 3 outcomes were (1) the density of neurologists by HRR, (2) the prevalence of neurologic conditions by HRR, and (3) the proportion of patients with neurologic conditions who were seen by neurologists by HRR. The density of neurologists was calculated by summing the number of neurologists per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries in each HRR and categorized into density quintiles. The prevalence of neurologic conditions was calculated by determining the number of patients with at least 1 visit for a neurologic condition to any provider (including neurologists and non-neurologists) per 1,000 FFS Medicare beneficiaries in each HRR. The proportion of patients with neurologic conditions who are seen by neurologists was computed by dividing the number of patients who had at least one E/M visit with a neurologist for a neurologic condition over the number of patients with at least 1 visit for a neurologic condition to any provider in each HRR.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe geographic variation in neurologist supply, summarize the prevalence of neurologic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries, and calculate the proportion of patients with neurologic conditions who were seen by neurologists, both in aggregate and across HRRs and neurologic conditions. To examine the differences in neurologist density explained by HRR characteristics, we used a linear regression model with neurologist density as dependent variable and HRR patient (beneficiaries' average age, sex, race/ethnicity, percent eligible for Medicaid, and Medicare Advantage [MA] participation rates) and geographic characteristics (academic medical center, census region, and proportion of zip codes in metropolitan areas) as independent variables. The coefficient (95% confidence interval [CI]) of HRR characteristics with p value <0.05 was reported. In addition, to examine the differences in the proportion of patients seen by neurologists across neurologist density quintiles, we used a linear regression model with the proportion of patients seen by a neurologist as the dependent variable and the prevalence of neurologic conditions, HRR patient, and HRR geographic characteristics as independent variables. The coefficient (95% CI) for each neurologist density quintile in the regression outcome represented the adjusted difference in the proportion of patients seen by neurologists between the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs and other quintiles. Mean predicted proportion of patients seen by neurologists for each neurologist density quintile was then calculated while holding all other variables constant. Our data met most linear regression assumptions (continuous dependent variable, iid criterion, no multicollinearity, no autocorrelation, and overall fit of the model). Several HRR outliers caused a relatively minor deviation to the normality of residuals. However, we have opted to include the outliers into our model since the threat to validity from dropping outliers is greater to the threat to validity from non-normality of residuals and results with or without outliers were similar. To define which conditions account for the majority of the relative difference in proportion seen by neurologist in the lowest vs highest neurologist density quintiles, we weighted the proportion of patients seen by neurologists with the prevalence of specific conditions in the lowest and highest neurologist density quintiles, respectively. We then calculated the weighted proportion of difference between the lowest and highest neurologist density quintiles for each neurologic condition and estimated the overall differences explained by each neurologic condition by dividing the weighted proportion of difference of each neurologic condition over the total weighted differences between the lowest and highest neurologist quintiles. Because the type of provider physician specialty is self-designated in the Medicare files, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) membership dataset to examine geographic distribution of neurologists. We also performed a sensitivity analysis that further limited the number of neurologic conditions to specific disorders (e.g., did not include back pain, dizziness, sleep disorders, and syncope). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA 16 (StataCorp). Map files containing HRR shape files were accessed from the Dartmouth Atlas Data.7 Geographic distribution of neurologists was mapped using ArcGIS Pro software (version 2.3.2; Esri, Redlands, CA).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was determined to be exempt from review and the requirement for obtaining patient written informed consent was waived by the Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability

The full dataset, 20% Medicare claim files, is available through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (cms.gov).

Results

Geographic Distribution of Neurologists

We identified 13,627 neurologists who provided office-based E/M services to Medicare beneficiaries within the 306 HRRs in this 2015 dataset. The figure shows the geographic distribution of neurologists at the HRR level by neurologist density quintile. The average density of neurologists was 22.3 (95% CI 20.6–24) per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries (table 2). Neurologist density by HRR varied 4-fold from 9.7 (95% CI 9.2–10.2) per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries in the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs to 14.2 (95% CI 13.9–14.6) in the 2nd quintile, 19 (95% CI 18.6–19.4) in the 3rd quintile, 25.5 (95% CI 24.8–26.1) in the 4th quintile, and 43.1 (95% CI 37.6–48.5) in the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs. The mean number of E/M visits per neurologist was 512 (95% CI 484–540), which varied by quintile of neurologist density from 668 (95% CI 588–748) in the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs to 612 (95% CI 555–670) in the 2nd quintile, 488 (95% CI 433–543) in the 3rd quintile, 455 (95% CI 405–506) in the 4th quintile, and 335 (95% CI 300–370) in the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs. In a sensitivity analysis using the AAN membership dataset to classify neurologists, we identified 14,935 neurologists practicing in clinical settings with average density of neurologists of 23 (95% CI 21–25) per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries. Geographic variation in the distribution of neurologists by the AAN membership dataset was similar to the pattern defined by Medicare data (figure).

Figure. Geographic Distribution of Neurologists at Hospital Referral Region Level.

(A) Distribution of neurologists using Medicare data. In the Medicare data, there are 13,627 neurologists. The average density of neurologists is 22.3 (95% CI 20.6–24) per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, with a range from 9.7 (95% CI 9.2–10.2) in the 1st (low) quintile Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs), 2nd quintile HRRs: 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] 13.9–14.6), 3rd quintile HRRs: 19 (95% CI 18.6–19.4), 4th quintile HRRs: 25.5 (95% CI 24.8–26.1), and 5th (high) quintile HRRs: 43.1 (95% CI 37.6–48.5). (B) Distribution of neurologists using American Academy of Neurology (AAN) membership dataset. In the AAN membership dataset, there are 14,935 neurologists practicing in clinical settings. The average density of neurologists is 23 (95% CI 21–25) per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, with a range from 7.7 (95% CI 7.1–8.3) in the 1st (low) quintile HRRs, 2nd quintile HRRs: 12.6 (95% CI 12.3–13), 3rd quintile HRRs: 18.2 (95% CI 17.6–18.8), 4th quintile HRRs: 26.8 (95% CI 26–27.8), and 5th (high) quintile HRRs: 49.6 (95% CI 44.2–55.1).

Table 2.

Hospital Referral Region (HRR) Characteristics by Quintile of Neurologist Density

Compared to the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs, the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs had a 3-fold greater number of Medicare beneficiaries (median 191,175 vs 72,263), lower percent of non-Hispanic White beneficiaries (76.7% vs 85.8%), higher proportion of regions with an academic medical center (68.9% vs 0%), higher proportion of urban classification (76.8% vs 47%), and higher proportion of regions located in Northeast census region (29.5% vs 11.5%) (p < 0.05). The percent eligible for Medicaid and MA participation rates did not differ across HRRs by neurologist density level. In a multivariate linear regression model predicting neurologist density, we found that neurologist density was associated with the average age of beneficiaries (coefficient 2.66 [95% CI 0.79–4.53], percent of beneficiaries eligible for Medicaid (coefficient 38.86 [95% CI 3.92–73.79]), presence of at least 1 academic medical center in the HRR (coefficient 16.39 [95% CI 13.03–19.76]), and the percent of zip codes in metropolitan areas (coefficient 0.09 [95% CI 0.02–0.15]) (p < 0.05).

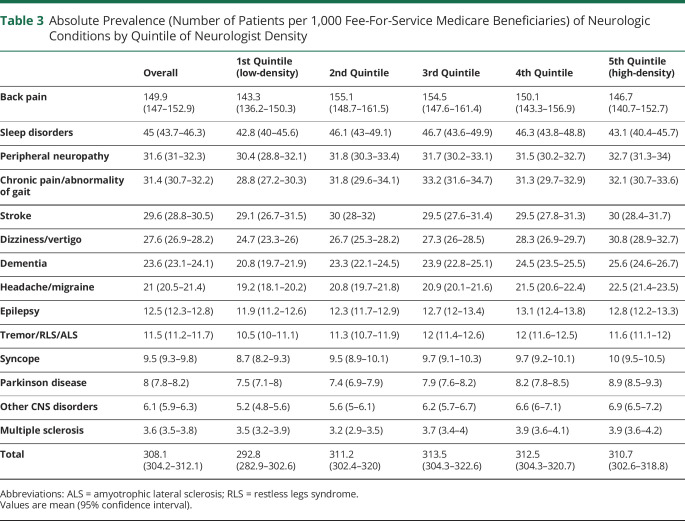

Prevalence of Neurologic Conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries by HRR

Nearly one-third (average 308.1 [95% CI 304.2–312.1] per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries) of Medicare beneficiaries had at least 1 visit for a neurologic condition and this proportion was similar across the quintiles of neurologist density (1st quintile [low]: 292.8 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries; 2nd quintile: 311.2; 3rd quintile: 313.5; 4th quintile: 312.5; 5th quintile [high]: 310.7) (table 3). Across HRRs, the most common neurologic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries were back pain (149.9 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries), sleep disorders (45 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries), and peripheral neuropathy (31.6 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries). The least common neurologic conditions were multiple sclerosis (MS) (3.6 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries), other CNS disorders (mainly comprising mild cognitive impairment) (6.1 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries), and Parkinson disease (PD) (8 per 1,000 FFS beneficiaries). There was small variation in the prevalence of the individual neurologic conditions by neurologist density quintile (table 3). Because some neurologic conditions are nonspecific, we also calculated the summary prevalence of neurologic conditions seen by neurologists excluding the nonspecific neurologic conditions (i.e., back pain, dizziness, sleep disorder, and syncope). We found that 151 (95% CI 149–153) per 1,000 FFS Medicare beneficiaries had at least 1 office visit for a specific neurologic condition and this gradually increased from the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs to the highest neurologist density quintiles HRRs (1st quintile [low]: 141.8 per 1,000 FFS Medicare; 2nd quintile: 150; 3rd quintile: 153; 4th quintile: 153.5; 5th quintile [high]: 156.6).

Table 3.

Absolute Prevalence (Number of Patients per 1,000 Fee-For-Service Medicare Beneficiaries) of Neurologic Conditions by Quintile of Neurologist Density

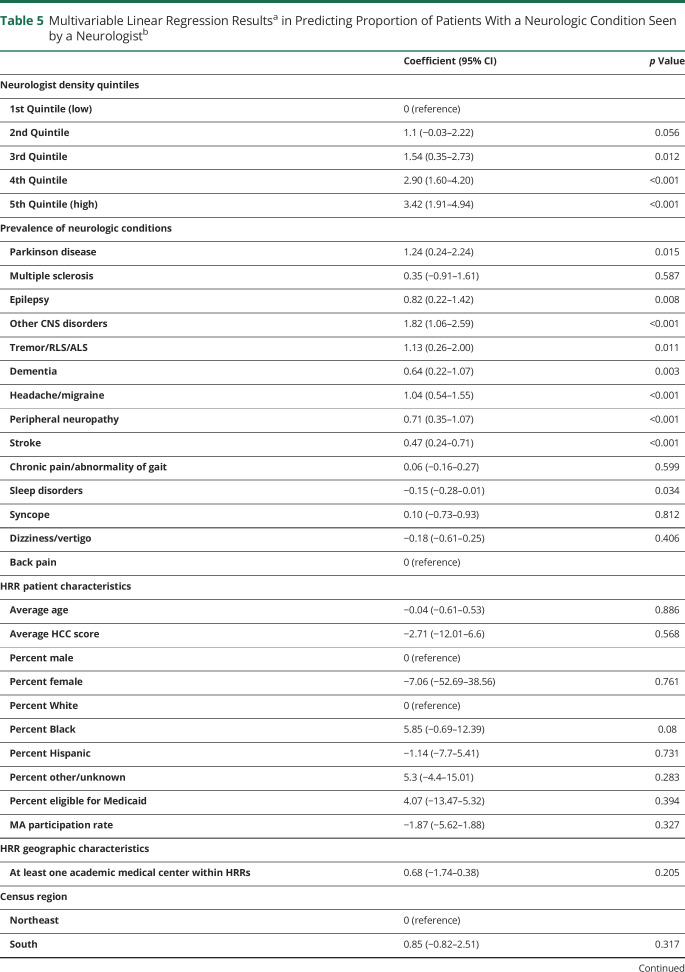

Proportion of Medicare Patients With Neurologic Conditions Seen by Neurologists by HRR

On average, 23.5% (95% CI 23%–24.1%) of patients with a neurologic condition had at least one E/M visit to a neurologist. The proportion of patients seen by a neurologist gradually increased across all quintiles from 20.6% (95% CI 19.3%–21.8%) in the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs to 21.8% (95% CI 20.8%–22.9%) in the 2nd quintile, 23.2% (95% CI 22.1%–24.2%) in the 3rd quintile, 25% (95% CI 23.9%–26.1%) in the 4th quintile, and 27.0% (95% CI 26%–38.1%) in the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs (absolute increase of 6.4%) (table 4). After adjusting for prevalence of neurologic conditions and HRR patient and geographic characteristics, the trend across all quintiles was still the same (1st quintile [low]: 21.7% [95% CI 20.8%–22.6%], 2nd quintile: 22.8% [95% CI 22%–23.7%], 3rd quintile: 23.3% [95% CI 22.5%–24.1%], 4th quintile: 24.6% [95% CI 23.8%–25.5%], 5th quintile [high]: 25.1% [95% CI 24.1%–26.2%]), but the difference between the highest and lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs attenuated to 3.4% (95% CI 1.9%–4.9%) (table 5). When we examined the proportion of patients with more specific neurologic conditions being seen by neurologists, we found that 40.6% (95% CI 39.9%–41.4%) of patients with specific neurologic conditions were seen by a neurologist and that the proportion increased from low to high neurologist density regions as well (1st quintile [low]: 36.4%, 2nd quintile: 38.7%, 3rd quintile: 40.1%, 4th quintile: 43.1%, 5th quintile [high]: 45%). After adjusting for the prevalence of neurologic conditions and HRR patient and geographic characteristics, the differences between the highest and the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs in the proportion of specific neurologic conditions seen by a neurologist decreased from 8.6% (absolute difference) to 4% (95% CI 1.7%–6.3%) (adjusted difference).

Table 4.

Absolute Proportion of Patients With a Neurologic Condition Seen by a Neurologist by Quintile of Neurologist Density

Table 5.

Multivariable Linear Regression Resultsa in Predicting Proportion of Patients With a Neurologic Condition Seen by a Neurologistb

At the condition level, there were differences in the patterns of the proportion of individuals with different conditions seen by a neurologist by quintile of neurologist density. The proportion of patients seen by neurologists was highest (>80%) for specific but uncommon conditions (e.g., PD, MS) and lowest (<11%) for common but nonspecific symptom conditions (e.g., back pain, dizziness/vertigo, syncope, sleep disorders) (table 4). For both PD and MS, while there was a gradual increase in trend in the proportion of patients seen by neurologists from the lowest to the highest neurologist density quintile, there was very little absolute increase (1%–3%) (e.g., PD: 1st quintile [low]: 82.9%, 2nd quintile: 84.8%, 3rd quintile: 84.9%, 4th quintile: 85.5%, 5th quintile [high]: 86.7%). For all other conditions (e.g., stroke, headache, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy), the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs had about 5%–7% more frequent neurologist involvement per condition than the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs.

After considering the prevalence of neurologic conditions in the regions, more than half of the overall weighted increase in the proportion of patients with neurologic conditions who were seen by a neurologist in the highest neurologist density quintile HRRs compared with that in the lowest neurologist density quintile HRRs comprised dementia (12.8%), back pain (12.6%), stroke (10.9%), peripheral neuropathy (10.5%), and chronic pain/abnormality of gait (10.1%) conditions (table 6). Very little of the increase comprised MS (1.5%) or PD (5%) conditions.

Table 6.

Relative Contribution of Individual Neurologic Conditions to the Overall Increase in the Proportion of Patients With a Neurologic Condition Seen by a Neurologist in Low Neurologist Density Regions Compared With High Neurologist Density Regions

Discussion

In this study, we present 3 principal findings about geographic variation in the neurologist workforce and neurologic care delivery to Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. First, we found that there is substantial geographic variation in the supply of neurologists; there was more than a 4-fold difference from the lowest to the highest neurologist density quintile regions. Second, we found that the prevalence of Medicare patients diagnosed with a neurologic condition varied little across regions. Considering the prevalence as an indirect measure of demand, this finding suggests that geographic variation in the demand for neurologic care is small. Third, we found that the proportion of Medicare patients with neurologic conditions who were seen by a neurologist increased somewhat in regions with greater neurologist density. However, the majority of the increase in neurologist care comprised dementia, pain conditions (back pain, peripheral neuropathy, and chronic pain/abnormality of gait), and stroke. Very little of the increase in neurologist care comprised PD or MS. This result suggests that an increase in the supply of neurologists may largely influence neurologist care delivery to certain conditions.

We extend the results of prior studies that found substantial geographic variation in the supply of neurologists by state and zip code to the HRR level, the geographic units that are perhaps most relevant to health care delivery.4,5 We found that regional variation in the density of neurologists was associated with the HRR population size, geographic location, and likely the presence of academic medical centers. Similar to other specialists (e.g., pulmonologists, urologists, radiation oncologists),9–11 neurologists were clustered in urban areas, in regions with greater population, or concentrated around tertiary care centers. While the highest neurologist density quintile regions had a 4-fold greater neurologist density than the lowest neurologist density quintile regions, neurologists in the highest neurologist density regions performed an average 50% fewer office visits compared with neurologists in the lowest neurologist density regions. This finding may relate to a higher proportion of neurologists in urban areas working at academic medical centers and having a lower concentration of direct patient care compared to neurologists in low neurologist density regions.

Characterizing the prevalence of neurologic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries by HRR provided several important insights. First, our findings highlight the very high prevalence of neurologic conditions among the Medicare population: about 1 in 3 Medicare beneficiaries had at least 1 office visit for a neurologic condition in 2015. Should this rate remain constant, with the US Census Bureau's projected aged 65+ population increasing from 49.2 million in 2016 to 70 million in 2034,12 the demand for neurologic care among the Medicare population would be expected to grow rapidly in the next decades. Second, the small difference in the prevalence of neurologic conditions across density quintiles of neurologists suggests that differential demand for patient care for specific neurologic conditions is not the explanation for the magnitude of variation in neurologist density across regions. Previous studies in cardiologists and neonatologists also reported that the incidence of diseases was unrelated to the supply of specialists.13,14

We also found that as neurologist density increased, the increase in the proportion of patients with a neurologic condition who were seen by a neurologist varied by condition. Whether all patients with a neurologic condition need to see neurologists or not, our findings suggest that increasing the supply of neurologists might be likely to increase the proportion of patients seen by neurologists for dementia, pain conditions (back pain, peripheral neuropathy, other chronic pain), and stroke. These conditions are all common and collectively accounted for the majority of the overall increase in patients seen by neurologists in the highest neurologist density regions compared with the lowest neurologist density regions. Increasing the supply of neurologists, on the other hand, is unlikely to significantly increase the proportion of patients seen by neurologists for PD and MS, since there is little variation across high and low neurologist density regions. It is possible that the demand for neurologist care is likely at least close to being met for PD and MS because of the high proportion (>80%) of neurologist involvement even in the lowest neurologist density quintile regions. On the other hand, if there is a rise in the demand for neurologist care for less-specific, but generally prevalent, neurologic conditions (i.e., back pain, headache, dizziness), then the potential for unmet need will likely be greatest in low neurologist density regions, although the ability to expand capacity by provider within regions is not known.

Understanding variation in the neurologist density by region and the proportion of patients with neurologic conditions seen by neurologists is important for future studies to evaluate how the regional supply of neurologists might affect clinical outcomes. Increased supply of primary care physicians by region was associated with increased self-reported health, increased life expectancy, and reduced all-cause and cause-specific mortality.15–22 Studies that have evaluated the association of neurologist care with patient outcomes, on the other hand, found mixed results.23–25 However, these individual-level observational studies are limited by unmeasured confounding, particularly relating to condition severity and patient preferences.26 Future studies exploring the association of neurologist regional density with outcomes would likely reduce unmeasured confounding since there should be less variation in disease severity by region than by individual. In addition, future attempts to obtain more balanced distribution of neurologists will need to recognize the challenge of influencing the provider's selection of their practice region. Not surprisingly, we found that neurologists seem to be drawn to regions with urban characteristics, including higher beneficiary density, older age of beneficiaries, presence of academic medical centers, and more zip codes in the metropolitan areas.

Our results are limited to adults with FFS Medicare and may not be generalizable to younger, privately insured, or MA populations. However, a prior study examining the determinants of neurologist visit among commercially insured and MA insured populations had similar conclusions.6 We included only a primary diagnosis of each patient visit and thus the prevalence of neurologic conditions may be underestimated. Also, we cannot determine the severity of the disease, although we expect little regional variation by condition. The optimal way to classify conditions as neurologic has not been defined previously. Although our primary method (based on most common diagnoses made by neurologists) might be overly inclusive, we balanced the analysis by also reporting per individual diagnostic category and selecting specific categories. Our analysis focused on neurologists in general without details about neurologist subspecialties. In addition, we did not have information about the proportion of practice in direct Medicare-insured patient care for each provider. Our regional variable was HRR, which comprises 306 units and captured a meaningful range of neurologist densities. Based on the data available, we were not able to use more granular regional units (e.g., hospital service areas).

We found substantial geographic variation in the supply of neurologists at the HRR level in the United States. Neurologic conditions were extremely common among Medicare beneficiaries and the prevalence of these conditions was similar across neurologist density quintile regions. The proportion of patients with neurologic conditions who were seen by a neurologist increased from the lowest neurologist density quintile regions to the highest neurologist density quintile regions. Most of the increase comprised dementia, pain, and stroke conditions, with very little of the increase comprising PD and MS conditions. These data provide an important foundation for future studies that aim to evaluate the association of neurologist density with patient outcomes and provide insight for policy makers when considering strategies in matching the demand for neurologic care with the appropriate supply of neurologists.

Acknowledgment

The study was proposed and executed by the American Academy of Neurology Health Services Research Subcommittee.

Glossary

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- CCS

Clinical Classifications Software

- CI

confidence interval

- E/M

evaluation and management

- FFS

Fee-for-Service

- HRRs

Hospital Referral Regions

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases–9

- ICD-10

International Classification of Diseases–10

- MA

Medicare Advantage

- MBSF

Medicare Beneficiary Summary File

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PD

Parkinson disease

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 87

Study Funding

The study was funded by the American Academy of Neurology. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

Dr. Lin reports no disclosures. Dr. Callaghan receives research support from Impeto Medical Inc, performs medical consultations for Advance Medical, consults for a PCORI grant, consults for the immune tolerance network, and performs medical legal consultations. Dr. Burke, Dr. Skolarus, Dr. Hill, and B. Magliocco report no disclosures. Dr. Esper performs medical legal consultations and serves as a consultant for NeuroOne, Incorporated, an EEG device company. Dr. Kerber reports no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/Nhttps://n.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011276 for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skolarus LE, Burke JF, Callaghan BC, Becker A, Kerber KA. Medicare payments to the neurology workforce in 2012. Neurology 2015;84:1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borlongan CV, Burns J, Tajiri N, et al. Epidemiological survey-based formulae to approximate incidence and prevalence of neurological disorders in the United States: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e78490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtzke JF. The current neurologic burden of illness and injury in the United States. Neurology 1982;32:1207–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology 2013;81:470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Goes DN, Ney JP, Garrison LP. Determinants of specialist physician ambulatory visits: a neurology example. J Med Econ 2019;22:830–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Dartmouth Institute. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: dartmouthatlas.org/. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed November 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croft JB, Lu H, Zhang X, Holt JB. Geographic accessibility of pulmonologists for adults with COPD: United States, 2013. Chest 2016;150:544–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aboagye JK, Kaiser HE, Hayanga AJ. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg 2014;149:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol 2009;181:760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060, report P25-1143. Silver Hill, MD: United States Census Bureau; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennberg JE. The Dartmouth Atlas of Cardiovascular Health Care. Hanover, NH: The Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, Dartmouth Medical School; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Little GA, Stukel TA, Chang CH. The uneven landscape of newborn intensive care services: variation in the neonatology workforce. Eff Clin Pract 2001;4:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman DC, Grumbach K. Does having more physicians lead to better health system performance?. JAMA 2008;299:335–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Politzer R, Xu J. Primary care, race, and mortality in US states. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Wulu J, Regan J, Politzer R. The relationship between primary care, income inequality, and mortality in US States, 1980-1995. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003;16:412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Xu J, Politzer R. Primary care, income inequality, and stroke mortality in the United States: a longitudinal analysis, 1985-1995. Stroke 2003;34:1958–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, et al. Primary care, infant mortality, and low birth weight in the states of the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi L, Starfield B. The effect of primary care physician supply and income inequality on mortality among blacks and whites in US metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1246–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starfield B, Shi L, Grover A, Macinko J. The effects of specialist supply on populations' health: assessing the evidence (Suppl Web Exclusives: W5-97-W5-107). Health Affairs 2005;24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis AW, Schootman M, Evanoff BA, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA. Neurologist care in Parkinson disease: a utilization, outcomes, and survival study. Neurology 2011;77:851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill CE, Lin CC, Burke JF, et al. Claims data analyses unable to properly characterize the value of neurologists in epilepsy care. Neurology 2019;92:e973–e987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callaghan BC, Burke JF, Kerber KA, et al. The association of neurologists with headache health care utilization and costs. Neurology 2018;90:e525–e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai A, Bekelis K, Zhao W, Ball PA, Erkmen K. Association of a higher density of specialist neuroscience providers with fewer deaths from stroke in the United States population. J Neurosurg 2013;118:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset, 20% Medicare claim files, is available through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (cms.gov).