Abstract

Objective

To describe sex differences in the presentation, diagnosis, and revision of diagnosis after early brain MRI in patients who present with acute transient or minor neurologic events.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of a prospective multicenter cohort study of patients referred to neurology between 2010 and 2016 with a possible cerebrovascular event and evaluated with brain MRI within 8 days of symptom onset. Investigators documented the characteristics of the event, initial diagnosis, and final diagnosis. We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the association between sex and outcomes.

Results

Among 1,028 patients (51% women, median age 63 years), more women than men reported headaches and fewer reported chest pain, but there were no sex differences in other accompanying symptoms. Women were more likely than men to be initially diagnosed with stroke mimic (54% of women vs 42% of men, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.24–2.07), and women were overall less likely to have ischemia on MRI (10% vs 17%, OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.36–0.76). Among 496 patients initially diagnosed with mimic, women were less likely than men to have their diagnosis revised to minor stroke or TIA (13% vs 20%, OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32–0.88) but were equally likely to have acute ischemia on MRI (5% vs 8%, OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.26–1.21).

Conclusions

Stroke mimic was more frequently diagnosed in women than men, but diagnostic revisions were common in both. Early brain MRI is a useful addition to clinical evaluation in diagnosing transient or minor neurologic events.

Acute neurologic events are common, and differentiating an acute cerebral ischemic event from a nonischemic event (a stroke mimic) can be challenging, especially in the setting of transient or minor neurologic symptoms.1,2 Nevertheless, an early and accurate diagnosis of cerebral ischemia is necessary for optimal secondary stroke prevention, including the rapid initiation of investigations and treatment.3,4

Prior research has shown that women are more likely to be diagnosed as having stroke mimic compared to men,2,5 but these studies have relied on imaging with CT, which is less sensitive for ischemia than MRI.6 Indeed, a substantial proportion of people with transient cerebrovascular events have evidence of acute ischemia on MRI.7,8 A recent study showed that early neuroimaging with MRI led to a revision of the initial diagnosis in 30% of the patients with clinically low-risk neurologic symptoms.9 In clinical practice, the initial diagnosis is frequently revised after investigations from stroke mimic to cerebral ischemia or vice versa. Differences in diagnostic revisions by sex are not well understood but are important because the initial diagnosis frequently guides the timing and extent of investigations, which can ultimately influence the final diagnosis.

Our aim was to describe sex differences in the presentation, diagnosis, and diagnostic revisions after investigations, including early brain MRI, in patients who presented with acute transient or minor neurologic events. We hypothesized that women might more frequently be initially diagnosed with stroke mimic compared to men but that the use of early brain MRI will lead to diagnostic revisions for both men and women.

Methods

We conducted a post hoc analysis of data from the Diagnosis of Uncertain-Origin Benign Transient Neurological Symptoms (DOUBT) study, which was a multicenter, international, prospective cohort study that enrolled patients presenting within 8 days of a possible minor stroke or TIA. Most patients were referred to the stroke neurology service after presenting to an emergency department, but this was not mandatory. All participants were assessed by a neurologist at least once.

The study methods have been previously published in detail.9 Briefly, the event must have been considered clinically low risk for cerebral ischemia, defined as nonmotor or nonspeech of any duration, motor or speech symptoms of short duration (≤5 minutes), or an NIH Stroke Scale score ≤3 if symptoms are ongoing, and the event must not have been felt to be definitively nonstroke according to the enrolling neurologist (e.g., subdural hemorrhage, brain tumor). All patients in the study underwent a brain MRI within 8 days of symptom onset as either inpatient or outpatient. Exclusion criteria included age <40 years, isolated monocular vision loss, prior clinical stroke, baseline dependence (modified Rankin Scale score ≥2), life expectancy of <1 year, or contraindication to MRI. Between June 1, 2010, and October 31, 2016, 1,028 participants were enrolled from 9 participating sites in Canada, the Czech Republic, and Australia.

The exposure of interest in the current analysis is patient sex. The primary outcome was revision of the clinical diagnosis from stroke mimic to cerebral ischemia. We also described the characteristics of the presenting event, the initial and final diagnoses, and diagnosis change from cerebral ischemia to stroke mimic.

Cerebral ischemia was defined as a diagnosis of ischemic stroke, definite TIA, or possible TIA. Definite TIA was defined as a sudden loss of focal brain function of presumed vascular origin with complete symptom resolution within 24 hours regardless of whether the MRI showed an acute infarct.10 Possible TIA was a separate diagnostic category in order to reflect the inherent uncertainty of diagnosing transient neurologic events when no acute infarct is seen on the MRI.1,6,11 Stroke mimic was defined as a nonstroke, non-TIA diagnosis. Among stroke mimics, a diagnosis of bizarre spell was used to categorize events that did not clearly fit any alternative neurologic or nonneurologic diagnoses.11

The initial diagnosis was documented prospectively by the treating neurologist at the time of enrollment, before the brain MRI, and the final one was determined retrospectively by the adjudication committee (S.B.C., F.M., and local site principal investigator) on the basis of the clinical documentation of the treating physician, study brain MRI, and results of any other investigations completed in clinical routine. The extent and results of investigations completed in clinical routine were not collected. Patient and event characteristics were recorded prospectively in a standardized case record form by the study investigator.

We expected migraine to be a common stroke mimic that is more prevalent in women12,13 and therefore performed a stratified analysis by the presence or absence of history of migraine. In addition, we conducted several sensitivity analyses by narrowing the final diagnosis of cerebral ischemia first by excluding the patients with possible TIA and then by excluding any patients who did not have evidence of objective acute ischemia on MRI.

Statistical Methods

We compared baseline patient and event characteristics between men and women using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. We used logistic regression analyses to evaluate the association between sex and revision of a diagnosis from stroke mimic to cerebral ischemia. We presented unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The baseline comorbid conditions that were statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) between men and women were included as covariates, and age was forced into the model. All statistical analyses were completed with Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment and undergoing brain MRI. The study was approved by the local institutional ethics boards at each participating site.

Data Availability

Data-sharing agreements and ethics approval do not allow the data to be made publicly available. Deidentified data can be made available on request to the senior author after approval by the ethics committees.

Results

We included 1,028 patients for analysis, of whom 522 (51%) were women and the median age was 63 (interquartile range 54–72) years. Most patients were enrolled from the neurology clinic (n = 732, 71%) after a referral from the emergency department; the remainder were enrolled directly from the emergency department. Although 85% (n = 878) of the patients scored zero on the NIH Stroke Scale, 36% (n = 370) reported some degree of ongoing symptoms at the time of the initial assessment. The baseline patient and event characteristics by sex are presented in table 1. Compared to men, women were less likely to have a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and hyperlipidemia, but they were more likely to have a history of migraine and self-reported stressors. We included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, hyperlipidemia, and self-reported stress as covariates in the multivariable models.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Clinical Features of the Transient Neurologic Event by Sex (n = 1,028)

With regard to the symptoms at presentation, women and men were equally likely to report symptoms of nausea or vomiting, feeling faint, feeling panic, experiencing shortness of breath, or having amnesia (table 1). Women were more likely than men to report accompanying symptoms of headache and other non–head-, non–chest-related pain, but men were more likely than women to report chest pain, and more women reported that their symptoms progressed over a period of >10 minutes.

More women than men were initially diagnosed with stroke mimic (54% of women vs 42% of men, OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.24–2.07). Migraine was the most common stroke mimic in women and men for both the initial and final diagnoses (table 2). Women were less likely than men to have a diffusion-weighted image (DWI) hyperintense lesion on MRI (10% vs 17%, OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.36–0.76) and were less likely to receive a final diagnosis of cerebral ischemia (30% vs 45%, OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.40–0.68, table 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of Stroke Mimic Diagnoses by Sex and by Initial and Final Diagnoses

Table 3.

ORs and 95% CIs of Diagnoses and Diagnosis Revision Comparing Women to Men

Of the 496 patients initially diagnosed with stroke mimic, women were less likely than men to have their diagnosis revised to cerebral ischemia after investigations, including brain MRI (13% vs 20%, OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32,0.88, table 3). The figure shows the final diagnosis (stroke mimic or cerebral ischemia) for each initial diagnosis stratified by sex. We performed several sensitivity analyses with more stringent criteria for a final diagnosis of cerebral ischemia by first excluding the patients with possible TIA and then excluding any patients who did not have evidence of objective ischemia on MRI. We found that the odds of diagnosis revision from mimic to cerebral ischemia was similar in women and men with these stricter criteria (table 3). Of the 532 patients initially diagnosed with cerebral ischemia, women were more likely than men to have their diagnosis revised to stroke mimic (49% vs 38%, OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.18–2.45).

Figure. Final Diagnosis (Stroke Mimic or Cerebral Ischemia) by Initial Diagnosis for Men and Women.

“Other” category includes miscellaneous diagnoses such as peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy, cranial neuropathy, demyelination, drug intoxication, metabolic disturbance, syncope, and space-occupying lesion. BPPV = benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Among the 256 patients with a history of migraine, 8% of women (n = 13) and 14% of men (n = 12) had a DWI lesion on MRI (Fisher exact test, p = 0.122), and among the 772 patients without migraine, 11% of women (n = 39) and 18% of men (n = 75) had a DWI lesion (Fisher exact test, p = 0.008). Among patients with a history of migraine, women were less likely than men to have their diagnosis revised from mimic to cerebral ischemia (8% [9 of 117] women vs 27% [12 of 45] men, OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07–0.52), but this was not the case among the patients without migraine (16% [27 of 166] women vs 18% [31 of 168] men, OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.42–1.34). The p value for multiplicative interaction between sex and history of migraine was 0.03.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of patients presenting to a stroke neurologist with low-risk transient or minor neurologic symptoms and enrolled from 9 sites internationally, we found that diagnosis revision from mimic to cerebral ischemia, and vice versa, occurred frequently after evaluation with an early brain MRI and other investigations completed in clinical routine. Women were less likely than men to have their diagnosis revised from mimic to cerebral ischemia when a broad definition of ischemia including minor stroke, definite TIA, and possible TIA was used. However, when a more restrictive definition of ischemia that includes only minor stroke or definite TIA or only MRI-confirmed stroke was used, the odds of diagnosis revision were similar between the 2 groups.

Consistent with prior studies, we found that women were overall more likely than men to be initially diagnosed with a stroke mimic.2,5 Nevertheless, among these patients, 5% of women and 8% of men had acute ischemia on MRI. The extent and urgency of performing investigations for mild and transient neurologic symptoms are often guided by the level of suspicion for cerebral ischemia by the treating physician. In the DOUBT study, early imaging with brain MRI was mandatory, but in clinical practice, MRI may not be routinely done if the diagnosis is felt to be a stroke mimic. Given that women were more likely than men to be initially diagnosed with stroke mimic, this may introduce differences in investigations by sex. While we did not record whether physicians would have ordered a clinical MRI outside of the study protocol, prior studies have shown that women, even after a diagnosed cerebrovascular event, were less likely to receive standard diagnostic tests compared to men.14,15 Our findings suggest that despite the lower rate of acute ischemia on brain MRI in women compared to men, systematic early imaging with MRI improves diagnostic accuracy in both sexes.

Clinical acumen is essential in the diagnosis of neurologic conditions, and clinicians rely heavily on symptom focality, type, and onset to differentiate transient symptoms of ischemic origin from other causes. In this study, we found that both women and men frequently report nonfocal symptoms, including feeling panic, shortness of breath, or faintness at the initial assessment. Early imaging is therefore a valuable adjunct to clinical assessments. We showed that diagnostic revision from mimic to ischemia occurred in almost all categories of initial stroke mimic diagnoses (figure). Although there were no patients with the initial diagnosis of epileptic seizure who had their diagnosis revised to cerebral ischemia, the small number of patients in this category limits the interpretation of this observation.

Differentiating migrainous phenomena from ischemia can be especially challenging. A history of migraine can contribute to sex differences in diagnosis because migraines are more common in women. We found that 8% of women and 14% of men with a history of migraine had DWI lesions on the MRI, suggesting that a comorbid diagnosis of migraine should not discourage clinicians from further investigating the patients for cerebral ischemia. Larger studies are needed to confirm this finding.

Finally, we showed that women were more likely than men to have their diagnosis revised from cerebral ischemia to stroke mimic, highlighting the importance of early investigation, including brain MRI, to establish an alternative diagnosis to avoid unnecessary long-term antiplatelet medications,16,17 to reduce stroke-related investigations, and to initiate the appropriate treatments to manage the alternative condition.

Our study has several limitations. First, the DOUBT study did not collect results of other investigations such as vascular imaging or cardiac tests, which were completed at the discretion of the treating physician and available to the investigators adjudicating the final diagnosis. Second, we acknowledge that MRI, even when done early, is not a perfectly sensitive tool to diagnose cerebral ischemia, particularly when the event is transient.6 The clinicians in the study were not blinded to sex, so we cannot ascertain that patient sex did not influence the final diagnosis. We could only enroll patients referred to neurology and therefore cannot mitigate any potential referral bias by sex. There are also limitations in the generalizability of our findings to patients ≤40 years of age. Finally, this is a post hoc analysis, and it could have been underpowered to detect small differences by sex.

Although cerebral ischemia is less common in women than men, diagnostic revisions were frequent in women and men systematically evaluated with early MRI brain. Standardized investigations in addition to clinical evaluation are important for the accurate diagnosis of cerebral ischemia, especially in the setting of transient or minor symptoms when diagnostic uncertainty is common.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- DOUBT

Diagnosis of Uncertain-Origin Benign Transient Neurological Symptoms

- DWI

diffusion-weighted image

- OR

odds ratio

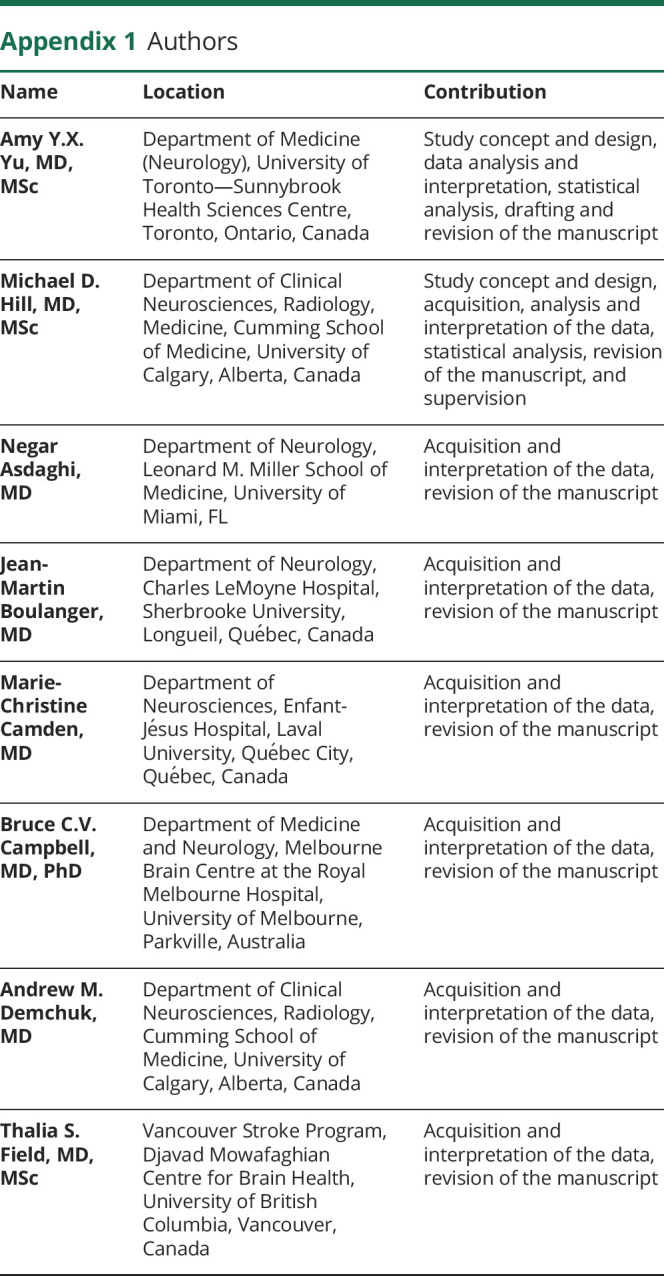

Appendix 1. Authors

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

Study Funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Disclosure

Dr. Yu reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Hill reported receiving grants from Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, and NoNO Inc. Dr. Boulanger reported receiving conference travel support from Pfizer. Dr. Camden reported receiving conference travel support from the University of Calgary. Dr. Demchuk reported receiving grants from the University of Calgary and receiving personal fees from Medtronic, Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Bayer. Dr. Field reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and in-kind study medication from Bayer Canada. Dr. Goyal reported receiving grants from Stryker; receiving personal fees from Medtronic, Stryker, and Microvention; and holding a licensing agreement with GE Healthcare on “Systems of Acute Stroke Diagnosis.” Dr. Mikulik reported grants from Project No. LQ1605. Dr. Moreau reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Stroke Consortium. Dr. Coutts reported receiving grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Genome Canada, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Go to Neurology.org/Nhttps://n.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011212 for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Prabhakaran S, Silver AJ, Warrior L, McClenathan B, Lee VH. Misdiagnosis of transient ischemic attacks in the emergency room. Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland) 2008;26:630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarnutzer AA, Lee SH, Robinson KA, Wang Z, Edlow JA, Newman-Toker DE. ED misdiagnosis of cerebrovascular events in the era of modern neuroimaging: a meta-analysis. Neurology 2017;88:1468–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutts SB, Modi J, Patel SK, Demchuk AM, Goyal M, Hill MD. CT/CT angiography and MRI findings predict recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: results of the prospective CATCH study. Stroke 2012;43:1013–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merino JG, Luby M, Benson RT, et al. Predictors of acute stroke mimics in 8187 patients referred to a stroke service. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:e397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazzelli M, Chappell FM, Miranda H, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging and diagnosis of transient ischemic attack. Ann Neurol 2014;75:67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack: proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1713–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Rooij FG, Vermeer SE, Goraj BM, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in transient neurological attacks. Ann Neurol 2015;78:1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutts SB, Moreau F, Asdaghi N, et al. Rate and prognosis of brain ischemia in patients with lower-risk transient or persistent minor neurologic events. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:1439–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration: WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:1545–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu AYX, Penn AM, Lesperance ML, et al. Sex differences in presentation and outcome after an acute transient or minor neurologic event. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:962–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gall SL, Donnan G, Dewey HM, et al. Sex differences in presentation, severity, and management of stroke in a population-based study. Neurology 2010;74:975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Brown DL, Morgenstern LB. Gender comparisons of diagnostic evaluation for ischemic stroke patients. Neurology 2005;65:855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1519–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:1036–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data-sharing agreements and ethics approval do not allow the data to be made publicly available. Deidentified data can be made available on request to the senior author after approval by the ethics committees.