Abstract

Components of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex are among the most frequently mutated genes in various human cancers, yet only SMARCB1/hSNF5, a core member of the SWI/SNF complex, is mutated in malignant rhabdoid tumors (MRT). HowSMARCB1/hSNF5 functions differently from other members of the SWI/SNF complex remains unclear. Here, we use Drosophila imaginal epithelial tissues to demonstrate that Snr1, the conserved homolog of human SMARCB1/hSNF5, prevents tumorigenesis by maintaining normal endosomal trafficking-mediated signaling cascades. Removal of Snr1 resulted in neoplastic tumorigenic overgrowth in imaginal epithelial tissues, whereas depletion of any other members of the SWI/SNF complex did not induce similar phenotypes. Unlike other components of the SWI/SNF complex that were detected only in the nucleus, Snr1 was observed in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Aberrant regulation of multiple signaling pathways, including Notch, JNK, and JAK/STAT, was responsible for tumor progression upon snr1-depletion. Our results suggest that the cytoplasmic Snr1 may play a tumor suppressive role in Drosophila imaginal tissues, offering a foundation for understanding the pivotal role of SMARCB1/hSNF5 in suppressing MRT during early childhood.

Introduction

The mammalian SWI/SNF complex, also termed the Brahma (Brm or Brg1) complex, regulates cellular processes such as cell differentiation and cell cycling. Numerous studies in mammals have shown that several subunits of this complex play a tumor-suppressor role in different tissues (1, 2). The Drosophila SWI/SNF complex regulates cell proliferation and differentiation in a similar manner to its mammalian counterpart. Two recent studies reported that the SWI/SNF complex also functions as a tumor suppressor in Drosophila neural stem cells (3, 4). For example, loss of components of the SWI/SNF complex resulted in aberrant dedifferentiation and proliferation of Drosophila neuroblasts.

Although several components of the SWI/SNF complex, such as SMARCA4/Brg1 (Brm in Drosophila), SMARCC1/BAF155 (Mor in Drosophila), SMARCB1 (also known as hSNF5/INI1), and ARID1 (Osa in Droosphila), have been found mutated in different human cancers, SMARCB1 is distinct from others. Cancers with mutations of other components of the SWI/SNF complex always have a number of more mutations in the recurrent samples, whereas cancers with loss of SMARCB1 essentially have no additional mutations (5). Mutation of SMARCB1 was first found in malignant rhabdoid tumors (MRT) that are very aggressive and highly lethal pediatric tumors (6, 7). No mutations in other subunits of the SWI/SNF complex have been found to be related to the MRTs, suggesting a potentially unique role of SMARCB1 in tumorigenesis. Components of the SWI/SNF complex in Drosophila, such as Brm, Mor and Osa, whereas not Snr1 (homolog of human SMARCB1), have been reported to be essential for the repression of Wingless target genes (8). Another study by Zraly and colleagues (9) has indicated that Snr1 is dispensable in some tissues where Brm complex activities are necessary. These studies suggest that Snr1 functions differently from the other components of the Brm complex in certain situations.

Drosophila has been used as a model for studying the mechanisms of tumorigenesis and for screening for antitumor drugs (10, 11). In addition to the conservation of genes between Drosophila melanogaster and humans, Drosophila tumors share many similarities to human tumors (12). Therefore, knowledge gained from studies of Drosophila tumors would help to understand human counterparts.

In this study, we report that Snr1, which is distinct from other components of the SWI/SNF complex, plays a unique role in suppressing tumor growth in the imaginal epithelial tissues. Loss of snr1 leads to neoplastic tumorigenic overgrowth, which is characterized by the disruption of cell polarity, failure of differentiation, and upregulation of invasion markers. Further experiments demonstrate that multiple signaling pathways, including Notch, JNK, and JAK/STAT, are deregulated in snr1 loss-of-function-induced tumorigenic discs. Deregulation of the pathways is caused by defects of the endosomal trafficking pathway, which may be attributed to the cytoplasmic function of Snr1 that is different from that of other components of the SWI/SNF complex. Our results have provided an alternative way to understand the mechanism how SMARCB1 suppresses MRTs during early childhood.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains and clonal analysis

Drosophila stocks used in this study were shown in the Supplementary Data. The snr119−21-mutant allele was generated by the CRISPR technique and procedures are essentially as previously described (13, 14). The target sequence is 5′-GGGCAGGGGATT-GAGGTCCAGG-3′, in which “AGG” (in bold) is the PAM site and “GGTCC” (in italic) is a cutting site for Sau96I, designed for identification of the mutagenesis. The forward primer sequence for producing the guiding RNA (gRNA) is: 5′-TAATACGACTC-ACTATAGGGCAGGGGATTGAGGTCCGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAAT-AGC-3′. The concentration of the gRNA used for injection was 50 ng/μL. Two independent F0 lines with mutations in the target sequence of snr1 were obtained.

Generation of UAS-HA-Snr1FL, UAS-HA-Snr1ΔNES, and UAS-HA-Snr1ΔC transgenic flies

The cDNA clone of snr1 from DGRC was used as a template to amply Snr1FL, Snr1ΔNES (nuclear export sequence, amino acids 248–260, was deleted), and Snr1ΔC (the 66 C-terminal amino acids were deleted). Only the coding sequences were amplified, and subsequently sequenced and subcloned into the pUASp vector by the Kpn I and Xba I restriction sites. An HA-tag was included in the N-terminal of each construct. After standard P element-mediated random germline transformation, several independent lines of transgenic flies of each genotype were obtained.

Anti-Brm antibody generation

Polyclonal rabbit antisera were raised against 6×His fusion proteins containing amino acids 501–775 of the Brm protein. To produce the 6×His fusion protein, an 825 bp fragment of brm was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-GTAGAATTCGCTGAACGAAAGCGTCGCCA-3′ and 5′-GTAGCGGCCGCTCATTCCTTGAGCGTACCATTAAC-3′ (restriction sites underlined). The amplified fragments were cloned into the EcoRI and NotI sites of PET-28a (+) (Novagen). 6×His-Brm fusion protein was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS, purified on Ni-NTA agarose columns (Qiagen) and used to immunize rabbits using standard protocol.

Immunocytochemistry and image capture

Antibody staining was performed as previously described (15). Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) labeling was carried out as previously described (16) and endocytosis assay in live wing disc cells was performed by following the protocol kindly provided by Dr. David Bilder (University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA; ref. 17). Rhodamine-conjugated and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probe, 1:100) were used to stain F-actin. Nuclei were co-stained with DAPI (1:1,000, Invitrogen) for 10 minutes at room temperature.

Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope in the Biological Science Imaging Resource Facility at Florida State University and Ziess LSM-800 confocal microscope in our laboratory. Figures were processed and arranged in Adobe Illustrator.

Results

Snr1 functions as tumor suppressor in Drosophila imaginal discs

Mutations in SMARCB1 are responsible for human MRT formation in children (6, 7), so to determine whether Snr1, the conserved Drosophila homolog of SMARCB1, has a similar tumor-suppressor role during development, we examined the function of snr1 in the imaginal disc, an epithelial tissue that has been widely used for modeling cancer in Drosophila (18, 19). Animals with homozygous snr1 mutation die at early larval stages (9). To circumvent early larval lethality, we used the Mosaic Analysis with a Repressible Cell Marker (MARCM) technique (20) to generate snr1 mosaic clones with a null allele (snr1R3; ref. 9). The area of snr1R3 mutant clones generated by the MARCM system in the wing imaginal disc was much smaller than that of the mock clones 72 hours after clonal induction (Supplementary Fig. S1D and S1E). The mutant cells underwent apoptosis, as indicated by the expression of an apoptotic marker, cleaved Drosophila Dcp-1, and were basally extruded (Supplementary Fig. S1B′ and S1E′). Mutant clones of another snr1 allele (snr119−21) showed similar phenotypes to those of snr1R3 (Supplementary Fig. S1C,C′ and S1F,F′). We further tested three independent RNAi lines targeting different coding regions of snr1. The efficiency of these RNAi lines was confirmed by immunostaining of Snr1 in the wing disc where Snr1 was barely detected in snr1-RNAi cells (Fig. 1D–D′′). Consistently, wing-imaginal-disc cells with snr1 knockdown induced by the flip-out Gal4 further confirmed strong apoptosis and basal extrusion phenotypes (Fig. 1B–C′′′).

Figure 1.

Knockdown of snr1 causes cell death in the wing pouch area and overgrowth in the notum region. A-A′′′, Wild-type wing disc as control expressing flip-out clones. B–C′′′, Wing disc-bearing snr1-RNAi mosaic cells induced by the fflip-out Gal4 with apical view (B-B′′′) and basal view (C-C′′′); clones were marked by the expression of GFP. D-D′′′, The Snr1 protein level is greatly reduced in snr1-depleted cells marked by the expression of GFP. E–H, Knockdown of snr1 causes both autonomous and nonautonomous overgrowths. E and F, The flip-out control and snr1RNAi wing discs stained with PH3; the notum of control disc in E outlined by dashed line has few PH3 labeling, and snrRNAi mosaic disc notum (F) has much more PH3 signals that are more prominent in neighboring wild-type area (arrow in F, compared with snr1RNAi area outlined by dashed line). G and H, The flip-out control and snr1RNAi wing discs labeled with BrdUrd; much more BrdUrd signals were observed in the snr1RNAi clone (dashed line) and neighboring wild-type cells (arrow).

Imaginal disc cells in the wing pouch area bearing a single mutation in tumor-suppressor genes, such as scribble (scrib), disc large (dlg), or lethal giant larvae (lgl), have previously been reported to be outcompeted by their wild-type neighbors (21–23). Prevention of cell competition by expression of oncogenic Ras (RasV12) in these mutant cells resulted in neoplastic tumor growth (21, 24). We reasoned that the cell lethality phenotype of snr1 mosaic discs could also be caused by cell competition, because in the Minute background, the area of snr1 mutant clones was significantly bigger than that observed in wild-type background (not shown). The cell death phenotype caused by cell competition was generally more pronounced in the wing pouch area (25, 26). Although the majority of snr1 knockdown cells in the wing pouch area underwent apoptosis (yellow circle, Fig. 1C′), we noticed an overgrowth phenotype in the notum region of the wing disc (outlined by red circles in Fig. 1B and C, compared with that in Fig. 1A). This overgrowth phenotype was detected in both snr1-depleted cells and their neighboring wild-type cells, as indicated by BrdUrd and PH3 labeling (Fig. 1E–H). Similar to mutations of ept and vps25, removal of snr1 caused mainly nonautonomous overgrowth (arrows in Fig. 1F and H). To prevent the cell death, we coexpressed the antiapoptotic protein p35 with flip-out Gal4 induced snr1 RNAi. Four days after RNAi induction, both wing and eye imaginal discs showed highly aggressive overgrowth; the size of either the wing or eye-antennal disc was at least two times larger than that of the wild-type disc (Fig. 2F and G). When snr1-RNAi and p35 were ectopically expressed under the control of a tissue-specific Gal4 driver, ptc-Gal4 or en-Gal4, some of the animals stayed at larval stages for up to ten days, and their wing discs showed massive overgrowth as well as disrupted anterior–posterior compartment borders (Supplementary Fig. S2A–S2D). It is unlikely that this tumorigenic overgrowth is caused by compensatory proliferation induced by “undead” cells (27–29), because coexpression of proapoptotic gene reaper (rpr) and p35 in a wild-type background did not result in a similar overgrown phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S3B, compared with Supplementary Fig. 3A). Together, these results suggest that Drosophila snr1 plays a tumor-suppressor role in imaginal discs.

Figure 2.

Loss of snr1 function in Drosophila imaginal disc induces neoplastic tumors. A, B, and E, Wing discs with coexpression of snr1-RNAi and p35 induced by the flip-out-Gal4 driver, stained with Arm (A), phalloidin to label F-actin (B), and Mmp1 (E). A′, B′, and E′, Transverse sections of the white lines in A, B, E. C and D, Eye discs with expression of p35 (C) or snr1-RNAi and p35 (D) labeled by Elav and Ci, and the MF indicated by arrows. Clones were marked by expression of GFP (A–E′). F and G, Wing (F) and eye-antennal discs (G) with p35 expression as control (left side of F and G) and snr1-RNAi and p35 (right side of F and G) stained with DAPI.

Depletion of snr1 leads to neoplastic tumorigenic overgrowth in Drosophila imaginal tissues

Drosophila epithelial tumors are normally either hyperplastic or neoplastic, with the latter showing defects in epithelial structure, differentiation, and tissue architecture (18). To determine the characteristics of snr1-LOF induced tumors, we first examined whether the apical-basal polarity was intact by staining the mosaic tissue with an apical marker atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), the basal lateral marker Dlg, and markers for adhesion junctions DE-Cadherin (DE-Cad) and Armadillo (Arm), as well as the actin cytoskeleton protein F-actin. In snr1-depleted tumor cells, we found that columnar epithelia were no longer maintained (Fig. 2A–B′). The overall levels of these markers in snr1-depleted cells were significantly increased compared with those in the wild-type neighbors, and subcellular localizations of the markers were disrupted (Fig. 2A–B′ and Supplementary Fig. S4D–S4F). Instead of its typical apical localization in the wild-type cells, aPKC was localized to all submembranes (Supplementary Fig. S4D), whereas Arm and DE-Cad were not restricted to adhesion junctions in snr1-knockdown cells as in the wild-type cells (Fig. 2A,A′, and Supplementary Fig. S4E). F-actin and Dlg, on the other hand, were evenly distributed in all submembranes of snr1-depleted cells (Fig. 2B,B′, and Supplementary Fig. S4F). From such aberrant localizations, we can infer that the apical-basal polarity is disrupted cell-autonomously in snr1-depleted epithelial cells.

Next, we examined whether cell differentiation is altered in snr1 LOF cells. In the wild-type eye disc, differentiated photoreceptor cells normally had Elav expression posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (MF) marked by accumulation of Ci (arrow in Fig. 2C), whereas snr1 LOF cells did not express this photoreceptor marker (Fig. 2D), indicating that terminal cell differentiation failed to occur in the absence of Snr1. This cell differentiation defect in snr1-depleted cells is probably not caused by loss of MF movement because the MF is anterior to snr1-depleted cells that lack Elav expression (arrow in Fig. 2D). In addition, we detected increased cell proliferation in snr1 knockdown cells, as revealed by increased BrdUrd incorporation, which labels proliferating cells (Supplementary Fig. S4A and S4B), and increased mitotic activity labeled by mitotic marker phospho-histone H3 (PH3; Supplementary Fig. S4C).

Another feature of neoplastic fly tumors is upregulated expression of the pro-invasion factor Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (Mmp-1; ref. 30). This marker was strongly expressed in snr1-depleted cells (Fig. 2E,E′). This upregulated Mmp-1 phenotype was also observed in wing discs carrying snr1-mutant clones in a less competitive background wherein their neighboring twin spots were eliminated due to mutation of STAT92E (STAT92E06346; Supplementary Fig. S5B′, compared with Supplementary Fig. S5A′). Cell polarity was also disrupted in wing disc cells of snr1 mutant clones, as indicated by F-actin staining (arrowhead in Supplementary Fig. S5D′, compared with Supplementary Fig. S5C′). Together, the upregulation of proinvasion factors, and the loss of polarity demonstrate that snr1–LOF-induced tumors are neoplastic tumors in the imaginal tissues.

Disruption of other components of the SWI/SNF remodeling complex fails to cause tumorigenic overgrowth in imaginal tissues

Although not related to MRTs, several other members of the SWI/SNF complex have been found to be mutated in other types of cancer (2). To determine whether disruption of other members of the Drosophila SWI/SNF remodeling complex would cause tumorigenesis in the imaginal disc, we knocked down each component by use of the same flip-out Gal4 driver. Similar to the removal of snr1, cells of brm or osa knockdown in imaginal epithelial tissues failed to survive and showed apparent cell death phenotype with basal extrusion in the wing pouch region (Supplementary Fig. S6), implicating the SWI/ SNF complex as required for cell survival. To block apoptosis, we introduced p35 into the knockdown cells. Unlike knock-down of snr1, removal of other components of the SWI/SNF complex appeared to cause no obvious overgrowth in the imaginal discs (Fig. 3B and C, compared with Fig. 3A); those mosaic clones still kept their intact cell polarity and differentiated properly (not shown). These results suggest that the tumor-suppressor role Snr1 plays in Drosophila imaginal discs is probably independent from other components of the SWI/SNF remodeling complex.

Figure 3.

Differences between Snr1 and other components of Drosophila SWI/SNF complex. A–C, Wing discs with mosaic clonal expression of snr1-RNAi and p35 (A), brm-RNAi and p35 (B), or osa-RNAi and p35 (C) under the flip-out-Gal4 inducer. D, Snr1 protein was not detected in wing disc cells with snr1R3 mutant clones (GFP negative), demonstrating the specificity of anti-Snr1 antibody. E–G, Wild-type wing disc cells with clonal expression of histone-RFP (hRFP, red) by flip-out Gal4 were immunolabeled with antibodies against Snr1 (E), Brm (F), or Osa (G); hRFP was used to label cell nuclei.

The subcellular localization of Snr1 is different from that of other components of the SWI/SNF complex

To understand why Snr1 has a unique role in suppressing tumor growth, we examined its subcellular localization in the wing disc cells. The SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex is expected to be localized in the nucleus, and indeed, Brm and Osa, two conserved members of this complex, were detected in the nucleus of the wing disc cells (Fig. 3E and G). In contrast, although endogenous Snr1 was mainly detected in the nucleus of disc cells, its expression was also detected in the cytoplasm of the cells (Fig. 3E). In addition, we examined the subcellular localization of Snr1, Brm and Osa in salivary gland cells. Consistent with the results in disc cells, Brm and Osa were exclusively localized in the nucleus of salivary gland cells (Supplementary Fig. S7B and S7C), whereas Snr1 was detected in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Supplementary Fig. S7A). To further explore the cytoplasmic localization of Snr1, we generated HA-tagged Snr1 full-length protein (HA-Snr1FL), and induced its expression in both the disc cells and salivary gland cells. In concordance with endogenous Snr1 protein, HA-Snr1FL localized to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm in these two type of cells (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Fig. S7D), which suggests a potential cytoplasmic role of Snr1, besides its nuclear function in Drosophila. This cytoplasmic localization of Snr1 is consistent with the report that SMARCB1 can shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm upon HIV-1 infection or under normal growth conditions (31–33).

Figure 7.

Construction of Snr1-truncated versions and their subcellular localization and rescue effects on tumorous wing discs caused by snr1 depletion. A, HA-tagged different forms of Snr1 under the UASp promoter. B–D, Close-up images of imaginal wing discs expressing HA-Snr1FL (B), HA-Snr1ΔNES (C), or HA-Snr1ΔC (D) were stained with anti-HA antibody; the transgenes were induced by the flip-out Gal4 driver and cells expressing the transgenes were marked by hRFP (red). E–H, Tumorigenic overgrowth phenotype of snr1-RNAi wing disc (E) is completely rescued by the expression of UASp-HA-Snr1FL (F), partially by the expression of UASp-HA-Snr1ΔC (G), but not by the expression of UASp-HA-Snr1ΔNES (H). I, Statistical data showing wing disc size difference in E–H. NS, nonsignificant.

Snr1 is required for endosomal trafficking

SMARCB1 has been suggested to regulate endocytosis by interacting with Dynamin-2 (Shibire in Drosophila; ref. 31). Because disruption of components involved in endosomal trafficking has been shown to cause tumorigenesis in Drosophila (17, 34, 35), we sought to determine whether cytoplasmic localization of Snr1 is related to a role in endosomal trafficking of membrane proteins. To this end, we first examined the expression of two endosomal trafficking components, Hepatocyte growth factor–regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) and the syntaxin Avalanche (Avl). Hrs is required for sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins to late endosomes, whereas Avl is localized to early endosomes (36). Both Hrs and Avl were cell-autonomously enriched in snr1-depleted wing disc cells (Fig. 4A and B and Supplementary Fig. S8B and S8G), though not in brm-, osa-, or bap180-knockdown cells (Supplementary Fig. S8C–S8E, S8H–S8J). The enrichment of Hrs and Avl was previously shown in mutant cells of Vps25, a neoplastic tumor suppressor, which is a component of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery that sorts membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies during endocytic trafficking to the lysosome (17, 36). Next, we examined the subcellular localization of transmembrane proteins: Delta (Dl), the ligand of the Notch signaling pathway, and its receptor, Notch, in snr1 mosaic imaginal wing discs. The distributions of both Dl and Notch proteins are highly dependent on membrane trafficking, and they were strongly upregulated in snr1-depleted cells as compared with neighboring wild-type cells (Fig. 4C–F). Again, accumulation of Dl or Notch was not found in brm- or osa-knockdown cells in the disc (Supplementary Fig. S9A, S9B, S9D, and S9E). The efficiency of brm or osa RNAi lines was confirmed by the undetectable or greatly reduced protein levels in the posterior compartment where brm or osa RNAi was induced (Supplementary Fig. S9C and S9F). We further performed an endocytosis assay with anti-Notch ECD to label Notch at the apical surface of live wing disc cells and confirmed the trafficking defect in snr1-depleted tumor cells (Fig. 4G and H). We therefore speculate that the cytoplasmic function of Snr1, which separates Snr1 from other SWI/SNF complex components, contributes to membrane trafficking.

Figure 4.

Snr1 is required for endocytic trafficking signaling. A–C, Wing discs harboring snr1-depleted cells labeled by expression of GFP were stained with Hrs (A), Avl (B), and NICD (C). D and F, Transverse sections of the white lines in C and E. Wing disc with snr1R3 mutant clones marked by the absence of GFP was stained with Dl (E). G and H, Endocytic assay with anti-Notch ECD (NECD) to label Notch at the apical surface of live wing discs.

Multiple signaling pathways are deregulated in snr1-depleted tumors

Endosomal trafficking is important for processing transmembrane ligands and receptors of many signaling pathway cascades (37, 38); therefore, disruption of the trafficking pathway usually leads to disregulation of signaling pathways (37, 39). Multiple signaling pathways, such as Notch, JAK/STAT and JNK, are found to be involved in tumorigenesis in Drosophila (17, 35, 40–43). We have shown that Notch and Dl proteins accumulated in snr1 mutant or knockdown cells (Fig. 4C–F). In these snr1 LOF tissues, Notch signaling activity was strongly upregulated as monitored by its direct reporters, E(spl)-CD2 and E (spl)-m7-lacZ (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. S10B). In contrast, Notch signaling was not affected in the wing disc upon depletion of brm or osa (Supplementary Fig. S10C and S10D). The overgrowth phenotype caused by snr1 depletion was partially suppressed by expression of Notch RNAi (Fig. 5H, compared with 5F, and Fig. 5K). These results suggest that Notch signaling is autonomously upregulated in snr1-LOF cells and augments the tumor phenotype caused by snr1 depletion in Drosophila imaginal tissues.

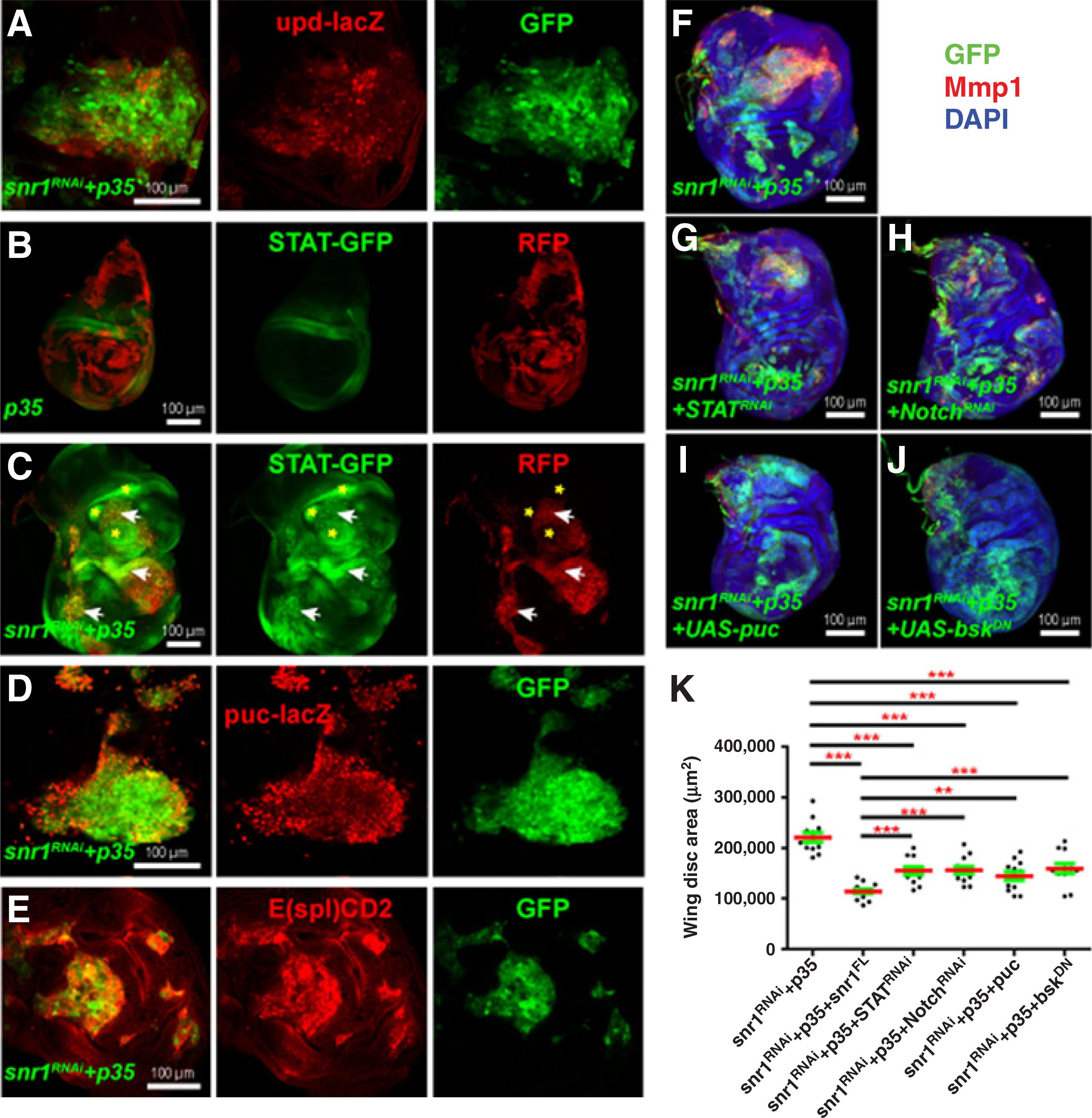

Figure 5.

Notch, JAK-STAT, and JNK signaling are upregulated in snr1-RNAi–induced wing disc tumor cells. A, D, and E, Close-up images of tumorous wing discs coexpressing snr1-RNAi and p35 driven by the flip-out Gal4, each with transgene upd-lacZ (A), puc-lacZ (D), or E(spl)CD2 (E). B, The flip-out Gal4-driven p35 control wing disc expressing transgene 10 X STAT92E-GFP (STAT-GFP). C, Tumorous wing disc caused by depletion of snr1 and expression of p35 under the control of the flip-out Gal4 labeled by the expression of RFP expressed STAT-GFP; arrows indicate cell-autonomous upregulation of STAT-GFP in snr1-RNAi tumors and asterisks show non-autonomous upregulation of STAT-GFP in their neighboring wild-type cells. Note B and C had the same imaging settings for STAT-GFP. F–K, Tumorigenic overgrowth of snr1-depleted wing disc can be partially suppressed by downregulation of JAK-STAT (G), Notch (H), or JNK (I and J) signaling. Upregulated expression of JNK reporter Mmp1 in snr1-RNAi tumors (F) was only suppressed by downregulation of JNK (I and J), but not by downregulation of JAK-STAT (G), Notch (H). Statistical data of F–J are shown in K.

The activation of JAK/STAT signaling has been reported to be essential for tumorigenesis in vps25, Tsg101, and Polycomb group genes mutant discs (17, 35, 41). In wild-type wing discs, Upd, the ligand for the JAK/STAT pathway, was barely detected. However, in wing discs with snr1-RNAi mosaic clones, Upd was upregulated (not shown). Induction of an upd-lacZ transgene was detected in many snr1 LOF clones (Fig. 5A), suggesting increased Upd expression is predominantly due to increased transcription. Furthermore, JAK/STAT signaling activity, assessed by the 10xSTA-T92E>GFP (STAT-GFP) reporter (44), was robustly hyperactivated in snr1-depleted tissues (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. S11B), whereas STAT-GFP was expressed at low levels in wild-type wing discs (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S11A) or wing discs carrying brm- or osa-RNAi mosaic clones (Supplementary Fig. S11C and S11D). Genetic interaction experiment suggested that increased JAK-STAT activity contributes to tumorigenic overgrowth upon snr1 loss (Fig. 5G, compared with 5F, and Fig. 5K).

The JNK signaling pathway is upregulated in many fly tumors. We have shown that expression of Mmp1, which is induced by JNK signaling, was upregulated in snr1–LOF-induced tumors (Fig. 2E,E′). To further analyze the activation of JNK signaling in snr1-LOF discs, we examined the expression of two direct reporters, puc-lacZ and TRE-GFP (45). Consistently, the labeling of both reporters was significantly increased cell-autonomously in snr1-depleted cells (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. S12A), whereas not in brm- or osa-depleted cells (Supplementary Fig. S12B and S12C). To determine whether JNK signaling was indeed involved in the tumorigenesis of snr1 LOF mosaic discs, we reduced JNK activity by expressing either a UAS-puc or UAS-bskDN construct. As expected, expression of either construct reduced Mmp1 levels in snr1 LOF clones (Fig. 5I and J, compared with 5F); it partially decreased the tissue size of snr1-depleted mosaic discs (Fig. 5K), thus implying that JNK activation was at least partially responsible for the tumorigenic phenotype caused by snr1 LOF.

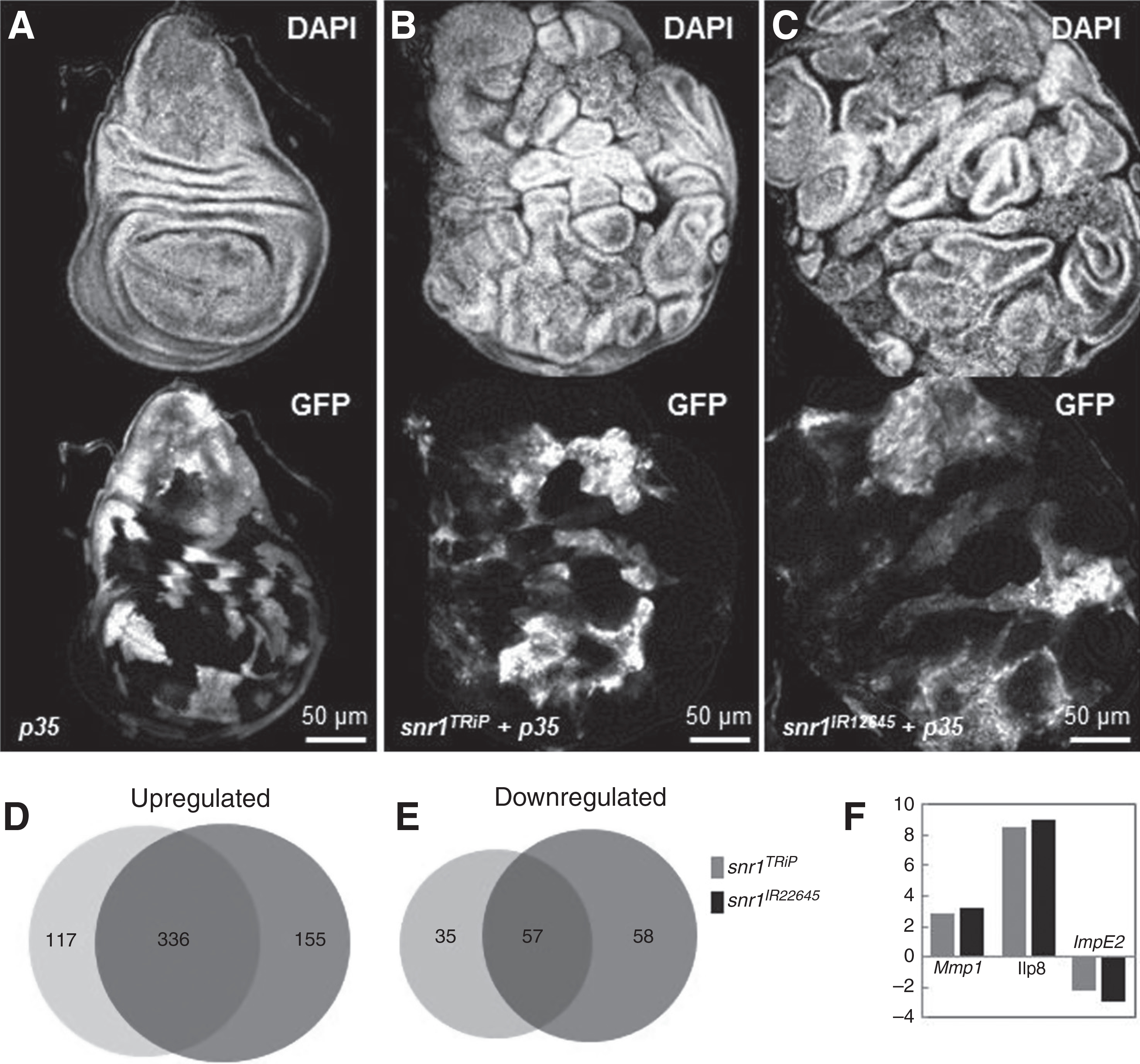

RNA-seq analyses of snr1-RNAi–induced tumors confirm aberrant regulation of multiple signaling pathways

To understand the global change of gene expression in snr1-depletion–induced tumors, we carried out RNA-seqencing (RNA-seq) analyses to compare the expression profile between control and snr1-depleted tumorigenic wing imaginal discs. We focused on changes common to neoplasm by sequencing cDNA libraries generated from two independent snr1 knockdown tumors that phenocopy each other (Fig. 6A–C). Analysis revealed 393 genes misregulated by at least two-fold increases/decreases in both mutant tissues (FDR <5%), with 336 upregulated and 57 downregulated (Fig. 6D and E). Differentially expressed genes included several previously identified neoplastic effectors, such as the proinvasion factor Mmp-1 (30), which has been discussed previously, and the pupation regulator insulin-like peptide 8 (Ilp8; Fig. 6F; refs. 46, 47). The transcriptome dataset therefore accurately captures the expression profile of neoplastic tissues, and contains genes that promote tumorigenesis upon snr1 loss. However, depletion of mmp-1 or ilp8 by RNAi was unable to suppress tumor growth caused by snr1 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. S13), similar to the case in avl-RNAi tumors (47).

Figure 6.

Comparison of RNA-seq analyses of flip-out control wild-type wing discs and snr1-depleted tumor discs. A–C, Wing discs from wandering instar larvae expressing only p35 (A), or with snr1-RNAi: snr1TRiP in B and snr1IR12645 in C, stained with DAPI; clonal cells marked by expression of GFP. D and E, Overlap of genes upregulated (D) or downregulated (E) with at least 2-fold change in snr1TRiP and snr1IR12645 wing imaginal discs. F, Genes previously implicated in neoplastic characteristics are differentially expressed in snr1-depleted tumor discs.

Consistent with the findings that multiple signaling pathways, including Notch, JAK-STAT, and JNK were deregulated, RNA-seq analysis confirmed that expression of at least one target of each pathway was upregulated (Table 1, Supplementary file S1). We previously showed that levels of Notch and Dl proteins were greatly upregulated in snr1-depleted cells; however, we did not detect significant increases of their mRNA levels in RNA-seq transcriptome analysis, which confirms that accumulation of Notch and Dl is due to endocytic defects in snr1 LOF cells, irrelevant to the transcription regulation activity of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex. In contrast, the mRNA level of the Notch signaling target E(spl)-m3 was increased nearly 2-folds in wing discs with snr1-depleted clones (Table 1). In addition, expression of multiple Notch targets such as chinmo, fruitless, abrupt, ken, and CG3835, as identified in Notch-induced hyperplastic wing discs by Djiane and his colleagues (48), was also significantly upregulated in snr1-depleted wing discs (Table 1, Supplementary File S1). Regarding JAK-STAT signaling, in accord with upd-lacZ upregulation (Fig. 5A), the level of upd-mRNA was greatly increased (7.41-folds, Table 1) in wing discs bearing snr1-depletion–induced tumors. In addition, transcriptional levels of the other two JAK-STAT pathway ligands, Upd2 and Upd3, were significantly increased as well (Table 1). For the JNK signaling pathway, mRNA levels of its targets puc and mmp-1 increased 2.9-fold and 8.5-fold, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, our RNA-seq analyses of snr1 RNAi wing disc tumors provided valuable and reliable information worth further exploration.

The cytoplasmic function of Snr1 contributes to tumorigenesis in the disc

Because Snr1 localizes to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, we wondered which disrupted functions of Snr1 contributed to the tumorigenic phenotype in imaginal discs: nuclear, cytoplasmic, or both? A conserved nuclear export sequence (NES) motif was found in the Drosophila Snr1 protein, similar to its human counterpart, SMARCB1 (31–33). We generated HA-tagged Snr1 protein with NES deletion (HA-Snr1ΔNES) under the UASp promoter (Fig. 7A). Immunostaining in both wing disc cells and salivary gland cells showed HA-Snr1ΔNES in the nucleus (Fig. 7C and Supplementary Fig. S7E), whereas the control HA-tagged wild-type Snr1 (HA-Snr1FL) was detected in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm in both type of cells (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Fig. S7D) resembling that of endogenous Snr1 protein (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S7A).

As shown above, snr1-depleted wing imaginal discs presented tumorigenic overgrowth (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2A–S2D), we therefore tested whether expression of NES-deleted Snr1 could suppress the tumorigenic phenotype. Expectedly, expression of HA-Snr1FL was able to fully rescue the tumorigenic phenotype in the snr1-RNAi + p35 wing discs (Fig. 7F, compared with Fig. 7E, and Fig. 7I), whereas expression of HA-Snr1ΔNES, of which the cytoplasmic function of Snr1 is compromised, failed to suppress overgrowth (Fig. 7H and I). A truncated human SNF5 protein lacking the 66 C-terminal amino acids (hSNF5ΔC) is accumulated in the cytoplasm (32). This 66-amino-acid sequence is highly conserved between Drosophila Snr1 and human SNF5, we therefore generated an HA-tagged Snr1 truncation mimicking this C-terminal deletion (HA-Snr1ΔC) under the UASp promoter. Similar to hSNF5ΔC, HA-Snr1ΔC is mainly localized in the cytoplasm of wing disc cells and salivary gland cells (Fig. 7D and Supplementary Fig. S7F). This construct partially suppressed the snr1-depleted tumor phenotype (Fig. 7G, compared with Fig. 7E, and Fig. 7I). These data suggest that the cytoplasmic function of Snr1 is required for its tumor-suppressing role in Drosophila imaginal disc.

Discussion

In Drosophila neuroblasts, the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex functions alone, or cooperatively with another chromatin remodeling factor, HDAC3, to suppress dedifferentiation of neural stem cells, suggesting its tumor suppressor role in neural stem cells (3, 4). In this scenario, there is no difference among components of the SWI/SNF complex. In Drosophila imaginal epithelial tissues, however, only knockdown of snr1 resulted in tumorigenic overgrowth, unlike depletion of other subunits of the SWI/SNF complex (Fig. 3A–C), indicating a unique and SWI/SNF-independent role of Snr1 in suppressing tumor progression in Drosophila imaginal epithelial tissues. Indeed, depletion of snr1 caused endosomal trafficking defects wherein transmembrane proteins and components of the endosomal trafficking pathways were accumulated in snr1-RNAi tumors (Fig. 4), whereas RNAi targeting against other SWI/SNF components did not result in such visible trafficking defects (Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9).

As a core component of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, only SMARCB1 is found mutated in childhood MRTs (5). An intrinsic distinction of SMARCB1 from other SWI/SNF subunits is that it can shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm via its nuclear export sequence (31–33). A recent study by Alfonso-Perez and his colleagues demonstrated that SMARCB1 directly interacts with the GTPase Dynamin-2 in the cytoplasm (31). Depletion of SMARCB1, but not other components of the SWI/SNF complex, destabilizes Dynamin-2 and impairs Dynamin-2-dependent endocytosis. Similar to SMARCB1, we found Snr1 was localized in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm of wing disc cells and salivary gland cells (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S7A), whereas other Drosophila SWI/SNF components, Brm and Osa, were only detected in the nucleus in these two type of cells (Fig. 3F and G and Supplementary Fig. S7B and S7C), which separates Snr1 from the SWI/SNF complex. Our novel findings that its cytoplasmic function is required for its tumor-suppression function provide a mechanistic explanation for snr1’s involvement in cell proliferation regulation and early childhood cancers.

Numerous studies in Drosophila have demonstrated that mutations of components of the trafficking signaling pathway, such as Avl, Vps25, and Tsg101, lead to tumorigenic overgrowth. In these tumors, multiple signaling pathways are disregulated. The snr1-depletion-induced tumors also show defects in Notch, JNK, and JAK-STAT signaling. Though in Avl, Vps25, and Tsg101 tumors, blocking Notch or JAK-STAT activation successfully blocked tumor growth, disruption of any individual pathways in snr1-tumors only mildly alleviated the tumorous phenotype, suggesting a more complicated involvement of signaling pathways in these tumors. In the mammalian system, the involvement of SMARCB1 in endosomal trafficking is related to its Dynamin interaction. This interaction may have been conserved through evolution, as knockdown of shibire, the Drosophila homolog of dynamin, also resulted in tumorous growth in the imaginal discs (not shown). It is tempting to hypothesize that the cytoplasmic function of Snr1 is the main driving force for its tumor-suppressor role.

The difference between childhood cancer and adult cancer may lie in the mutation rates. In childhood tumors, mutant cells do not have enough time to accumulate significant numbers of mutations; therefore, genes responsible for such diseases must be multifunctional. Snr1/SMARCB1 might be a perfect example in this regard; its functional roles in both chromatin remodeling and endocytic trafficking fit into its function of growth regulation.

The tumor-suppressor role of Snr1 appears to be tissue specific; in follicle cells of developing egg chambers, another type of epithelial cell, the removal of snr1 through mutation or RNAi did not cause tumorigenesis, even in the presence of p35. In humans, SMARCB1-associated tumors are observed in soft tissues. Therefore, the involvement of this gene may depend on its specific role in a tissue, or if there is a redundancy in certain tissues where loss of snr1 might be compensated by a different gene. In Drosophila neural stem cells, several components of the SWI/SNF complex are required for preventing tumorigenesis through proper temporal patterning and self-renewal control (4). These components include core components of the SWI/SNF complex, Brm, Mor, and Snr1, and BAP-specific subunit Osa, though not any subunits of the PBAP complex, underlining the functional specificity of the SWI/SNF complex. Therefore, our study on Snr1’s cytoplasmic role in Drosophila imaginal discs provides insight into understanding the occurrence and progression of human MRTs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Trudi Schupbach, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, the National Institute of Genetics, and the TRiP at Harvard Medical School for fly stocks; Andrew Dingwall, Hugo J. Bellen, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies; David Bilder for the endocytosis assay protocol; Lexiang Yu for technical assistance; Thomas J. Fellers from the Biological Science Imaging Resource of Florida State University (FSU) for technical support; the Translational Science Laboratory of the FSU College of Medicine for running the Illumina HiSeq machine; Jen Kennedy and Gabriel Calvin for critical reading and helpful comments on the article; and members of the Deng and Jiao laboratories for feedback and suggestions.

Grant Support

W.-M. Deng is supported by the NIH (grant number R01GM072562) and the National Science Foundation (grant number IOS-1052333). R. Jiao is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81470846, 31271573, and 31529004) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA04020413–02).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Roberts CW, Biegel JA. The role of SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer Biol Ther 2009;8:412–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reisman D, Glaros S, Thompson EA. The SWI/SNF complex and cancer. Oncogene 2009;28:1653–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koe CT, Li S, Rossi F, Wong JJ, Wang Y, Zhang Z, et al. The Brm-HDAC3-Erm repressor complex suppresses dedifferentiation in Drosophila type II neuroblast lineages. Elife 2014;3:e01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eroglu E, Burkard TR, Jiang Y, Saini N, Homem CC, Reichert H, et al. SWI/SNF complex prevents lineage reversion and induces temporal patterning in neural stem cells. Cell 2014;156:1259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RS, Stewart C, Carter SL, Ambrogio L, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, et al. A remarkably simple genome underlies highly malignant pediatric rhabdoid cancers. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biegel JA, Zhou JY, Rorke LB, Stenstrom C, Wainwright LM, Fogelgren B. Germ-line and acquired mutations of INI1 in atypical teratoid and rhabdoid tumors. Cancer Res 1999;59:74–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Versteege I, Sevenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck MF, Ambros P, Handgretinger R, et al. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature 1998;394:203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins RT, Treisman JE. Osa-containing Brahma chromatin remodeling complexes are required for the repression of wingless target genes. Genes Dev 2000;14:3140–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zraly CB, Marenda DR, Nanchal R, Cavalli G, Muchardt C, Dingwall AK. SNR1 is an essential subunit in a subset of Drosophila brm complexes, targeting specific functions during development. Dev Biol 2003;253: 291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miles WO, Dyson NJ, Walker JA. Modeling tumor invasion and metastasis in Drosophila. Dis Model Mech 2011;4:753–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gladstone M, Su TT. Chemical genetics and drug screening in Drosophila cancer models. J Genet Genomics 2011;38:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gateff E Malignant neoplasms of genetic origin in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 1978;200:1448–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Z, Chen H, Liu J, Zhang H, Yan Y, Zhu N, et al. Various applications of TALEN- and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination to modify the Drosophila genome. Biol Open 2014; 3:271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Z, Ren M, Wang Z, Zhang B, Rong YS, Jiao R, et al. Highly efficient genome modifications mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in Drosophila. Genetics 2013;195:289–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie G, Yu Z, Jia D, Jiao R, Deng WM. E(y)1/TAF9 mediates the transcriptional output of Notch signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Sci 2014;127:3830–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun JJ, Deng WM. Notch-dependent downregulation of the homeodomain gene cut is required for the mitotic cycle/endocycle switch and cell differentiation in Drosophila follicle cells. Development 2005;132:4299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaccari T, Bilder D. The Drosophila tumor suppressor vps25 prevents nonautonomous overproliferation by regulating notch trafficking. Dev Cell 2005;9:687–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariharan IK, Bilder D. Regulation of imaginal disc growth by tumor-suppressor genes in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet 2006;40:335–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Dissecting social cell biology and tumors using Drosophila genetics. Annu Rev Genet 2013;47:51–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron 1999; 22:451–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brumby AM, Richardson HE. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. EMBO J 2003;22:5769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamori Y, Bialucha CU, Tian AG, Kajita M, Huang YC, Norman M, et al. Involvement of Lgl and Mahjong/VprBP in cell competition. PLoS Biol 2010;8:e1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igaki T, Pastor-Pareja JC, Aonuma H, Miura M, Xu T. Intrinsic tumor suppression and epithelial maintenance by endocytic activation of Eiger/TNF signaling in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2009;16:458–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagliarini RA, Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science 2003;302:1227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lolo FN, Casas-Tinto S, Moreno E. Cell competition time line: winners kill losers, which are extruded and engulfed by hemocytes. Cell Rep 2012;2: 526–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Beco S, Ziosi M, Johnston LA. New Frontiers in cell competition. Dev Dyn 2012;241:831–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Morata G. Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development 2004;131:5591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryoo HD, Gorenc T, Steller H. Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev Cell 2004;7:491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huh JR, Guo M, Hay BA. Compensatory proliferation induced by cell death in the Drosophila wing disc requires activity of the apical cell death caspase Dronc in a nonapoptotic role. Curr Biol 2004; 14:1262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhlirova M, Bohmann D. JNK- and Fos-regulated Mmp1 expression cooperates with Ras to induce invasive tumors in Drosophila. EMBO J 2006;25:5294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alfonso-Perez T, Dominguez-Sanchez MS, Garcia-Dominguez M, Reyes JC. Cytoplasmic interaction of the tumour suppressor protein hSNF5 with dynamin-2 controls endocytosis. Oncogene 2014;33: 3064–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craig E, Zhang ZK, Davies KP, Kalpana GV. A masked NES in INI1/hSNF5 mediates hCRM1-dependent nuclear export: implications for tumorigenesis. EMBO J 2002;21:31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turelli P, Doucas V, Craig E, Mangeat B, Klages N, Evans R, et al. Cytoplasmic recruitment of INI1 and PML on incoming HIV preintegration complexes: interference with early steps of viral replication. Mol Cell 2001;7:1245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson BJ, Mathieu J, Sung HH, Loeser E, Rorth P, Cohen SM. Tumor suppressor properties of the ESCRT-II complex component Vps25 in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2005;9:711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moberg KH, Schelble S, Burdick SK, Hariharan IK. Mutations in erupted, the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101, elicit non-cell-autonomous overgrowth. Dev Cell 2005;9: 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H, Bilder D. Endocytic control of epithelial polarity and proliferation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 2005;7:1232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer JA, Eun SH, Doolan BT. Endocytosis, endosome trafficking, and the regulation of Drosophila development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006;22: 181–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:17615–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fortini ME, Bilder D. Endocytic regulation of Notch signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2009;19:323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez AM, Schuettengruber B, Sakr S, Janic A, Gonzalez C, Cavalli G. Polyhomeotic has a tumor suppressor activity mediated by repression of Notch signaling. Nat Genet 2009;41:1076–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Classen AK, Bunker BD, Harvey KF, Vaccari T, Bilder D. A tumor suppressor activity of Drosophila Polycomb genes mediated by JAK-STAT signaling. Nat Genet 2009;41:1150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, Nakamura M, Betsumiya A, Igaki T. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature 2012;490: 547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enomoto M, Igaki T. Src controls tumorigenesis via JNK-dependent regulation of the Hippo pathway in Drosophila. EMBO Rep 2012; 14:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bach EA, Ekas LA, Ayala-Camargo A, Flaherty MS, Lee H, Perrimon N, et al. GFP reporters detect the activation of the Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway in vivo. Gene Expr Patterns 2007;7:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chatterjee N, Bohmann D. A versatile PhiC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and Nrf2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e34063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garelli A, Gontijo AM, Miguela V, Caparros E, Dominguez M. Imaginal discs secrete insulin-like peptide 8 to mediate plasticity of growth and maturation. Science 2012;336:579–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colombani J, Andersen DS, Leopold P. Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science 2012;336: 582–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Djiane A, Krejci A, Bernard F, Fexova S, Millen K, Bray SJ. Dissecting the mechanisms of Notch induced hyperplasia. EMBO J 2013;32:60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.