Key Points

Question

Is a team-based community health worker and advanced practice clinician (including nurse practitioners or physician assistants) intervention emphasizing evidence-based care, self-management, lifestyle change, and medication adherence superior to usual care for controlling blood pressure after stroke in safety-net settings?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 487 adults with recent stroke or transient ischemic attack, there was no difference between usual care and the multifaceted team-based intervention in blood pressure control at 12 months.

Meaning

These findings suggest that additional research is needed to determine the optimal care model for controlling risk factors after stroke in safety-net settings.

This randomized clinical trial examines the effect of a multifaceted team intervention vs usual care on systolic blood pressure (SBP) among patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in safety-net settings.

Abstract

Importance

Few stroke survivors meet recommended cardiovascular goals, particularly among racial/ethnic minority populations, such as Black or Hispanic individuals, or socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Objective

To determine if a chronic care model–based, community health worker (CHW), advanced practice clinician (APC; including nurse practitioners or physician assistants), and physician team intervention improves risk factor control after stroke in a safety-net setting (ie, health care setting where all individuals receive care, regardless of health insurance status or ability to pay).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial included participants recruited from 5 hospitals serving low-income populations in Los Angeles County, California, as part of the Secondary Stroke Prevention by Uniting Community and Chronic Care Model Teams Early to End Disparities (SUCCEED) clinical trial. Inclusion criteria were age 40 years or older; experience of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) no more than 90 days prior; systolic blood pressure (BP) of 130 mm Hg or greater or 120 to 130 mm Hg with history of hypertension or using hypertensive medications; and English or Spanish language proficiency. The exclusion criterion was inability to consent. Among 887 individuals screened for eligibility, 542 individuals were eligible, and 487 individuals were enrolled and randomized, stratified by stroke type (ischemic or TIA vs hemorrhagic), language (English vs Spanish), and site to usual care vs intervention in a 1:1 fashion. The study was conducted from February 2014 to September 2018, and data were analyzed from October 2018 to November 2020.

Interventions

Participants randomized to intervention were offered a multimodal coordinated care intervention, including hypothesized core components (ie, ≥3 APC clinic visits, ≥3 CHW home visits, and Chronic Disease Self-Management Program workshops), and additional telephone visits, protocol-driven risk factor management, culturally and linguistically tailored education materials, and self-management tools. Participants randomized to the control group received usual care, which varied by site but frequently included a free BP monitor, self-management tools, and linguistically tailored information materials.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was change in systolic BP at 12 months. Secondary outcomes were non–high density lipoprotein cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, body mass index, antithrombotic adherence, physical activity level, diet, and smoking status at 12 months. Potential mediators assessed included access to care, health and stroke literacy, self-efficacy, perceptions of care, and BP monitor use.

Results

Among 487 participants included, the mean (SD) age was 57.1 (8.9) years; 317 (65.1%) were men, and 347 participants (71.3%) were Hispanic, 87 participants (18.3%) were Black, and 30 participants (6.3%) were Asian. A total of 246 participants were randomized to usual care, and 241 participants were randomized to the intervention. Mean (SD) systolic BP improved from 143 (17) mm Hg at baseline to 133 (20) mm Hg at 12 months in the intervention group and from 146 (19) mm Hg at baseline to 137 (22) mm Hg at 12 months in the usual care group, with no significant differences in the change between groups. Compared with the control group, participants in the intervention group had greater improvements in self-reported salt intake (difference, 15.4 [95% CI, 4.4 to 26.0]; P = .004) and serum CRP level (difference in log CRP, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.7 to −0.1] mg/dL; P = .003); there were no differences in other secondary outcomes. Although 216 participants (89.6%) in the intervention group received some of the 3 core components, only 35 participants (14.5%) received the intended full dose.

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial of a complex multilevel, multimodal intervention did not find vascular risk factor improvements beyond that of usual care; however, further studies may consider testing the SUCCEED intervention with modifications to enhance implementation and participant engagement.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01763203

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 4 strokes in the United States are recurrent.1 Combining dietary changes, physical activity, and targeted medications can reduce the cumulative risk for recurrent vascular events after stroke by 80%.2 Nevertheless, risk factor control among survivors of stroke remains poor, with only a small portion of individuals reaching recommended targets.3,4,5,6 Independent factors associated with poor risk factor control include minority race/ethnicity (eg, Black or Hispanic), poverty, and lower education level.4,5,6

The chronic care model (CCM), which incorporates self-management support, delivery system redesign, clinical information systems with decision support for applying evidence-based care guidelines, health care system leadership engagement, and community resources, has been effective in improving outcomes while reducing costs for chronic conditions.7,8,9,10 A randomized clinical trial of a CCM-based intervention by Cheng et al11 did not show a benefit beyond usual care in blood pressure (BP) reduction in a predominantly Hispanic population treated for stroke in a safety-net setting (ie, health care setting where all individuals receive care, regardless of health insurance status or ability to pay). The intervention, delivered solely within the health care system by advanced practice clinicians (APCs; including nurse practitioners or physician assistants), did not address home and community barriers to lifestyle change or transportation barriers to accessing care.

We hypothesized that community health workers (CHWs) could more effectively address lifestyle factors, health literacy, medication adherence, and obstacles to behavior change. Therefore, we developed a multilevel, multicomponent, complex CCM-based team (including an APC, a CHW, and a physician) intervention for improving poststroke risk factor control.12 The intervention redesigned care at the health care system level with evidence-based care protocols with real-time electronic decision support and enhanced care coordination and at the patient level by targeting health and stroke literacy, medication adherence, self-management skills, and lifestyle (eFigure in Supplement 1). We tested the efficacy of the Secondary Stroke Prevention by Uniting Community and Chronic Care Model Teams Early to End Disparities (SUCCEED) intervention in improving risk factor control after stroke at 12 months in a safety-net setting.

Methods

Institutional review board approvals were obtained at University of California, Los Angeles and at each of the 5 sites (or through reliance agreements with UCLA). All participants provided written informed consent. This study is reported following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The Trial Protocol is presented in Supplement 2.

Setting and Participants

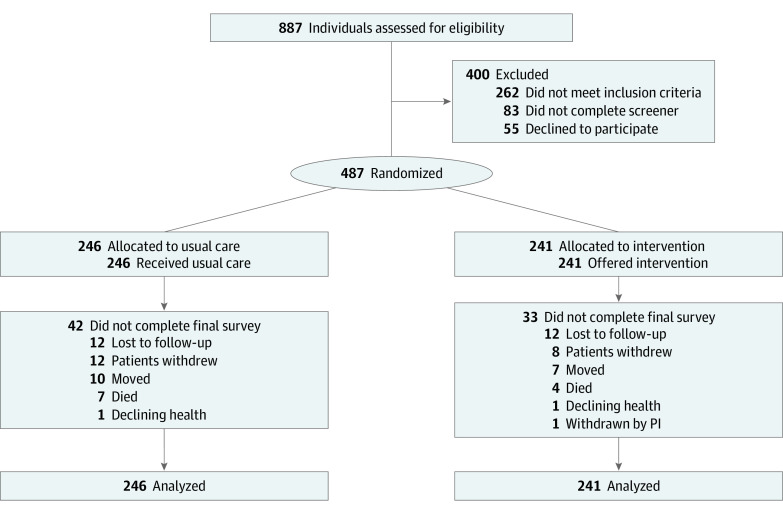

Study details have been previously published.12 The intervention was framed by the Health Belief Model.13 Briefly, of 887 screened participants, 542 were eligible, and 487 were enrolled from February 2014 through August 2017 from 4 Los Angeles County Department of Health Services public safety-net health care system hospitals (ie, Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, Harbor-UCLA, LAC+USC Medical Center, and Olive View Medical Center) and 1 additional hospital (ie, Cedars Sinai) serving low-income zip codes (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were age 40 years or older; experience of transient ischemic attack (TIA), ischemic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage within the last 90 days; and elevated systolic BP. Elevated systolic BP was defined as greater than 120 mm Hg, consistent with existing guidelines.14 During the course of the trial, evidence of a potential J-shaped curve emerged among individuals who survived stroke, with a suggestion of higher risk for cardiovascular events with strict BP control.15,16,17,18 Therefore, 16 months after initiating the trial (after enrolling 154 participants), the systolic BP goal at 12 months was increased from less than 120 mm Hg to less than 130 mm Hg. Correspondingly, inclusion criteria were revised to systolic BP 130 mm Hg or greater or 120 to 130 mm Hg in individuals with a history of hypertension or using antihypertensive medications prior to the stroke or TIA. Participants were excluded if they were unable to communicate understanding the study during the informed consent process or lacked English or Spanish proficiency.

Figure 1. Consort Flow Diagram of the SUCCEED Trial.

PI indicates principal investigator; SUCCEED, Secondary Stroke Prevention by Uniting Community and Chronic Care Model Teams Early to End Disparities.

Study Procedures

After baseline data collection, eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to control vs intervention, stratified by stroke type (TIA or ischemic vs hemorrhagic), language (English vs Spanish), and study site. Randomization schedules were developed using computer-assisted stratified randomization of a block size of 4 and programmed into the Research Electronic Data Capture (Vanderbilt University) database.12 Randomization schedules were only accessible to the project manager (M.A.-R.), principal investigators (A.T. and B.G.V.), and data manager (F.B.). Research assistants (C.M., D.G., L.M., M.F., E.L., and S.V.) obtaining outcome assessments were blinded to the randomization arm throughout follow-up and did not interact with care teams.12

Usual Care and Intervention

Participants randomized to the control group received usual care, which varied by study site (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Most study participants (325 participants [66.7%]) were enrolled at a site that provided free BP monitors, self-management tools (BP and glucose logs), and linguistically tailored educational materials as usual care.

In addition to usual care, individuals randomized to the intervention arm were offered at least 3 APC clinic visits; at least 3 CHW home visits; telephone visits; protocol-driven risk factor management; electronic decision support for clinicians; coordination of care; BP monitors (HEM-711 DLX; Omron Healthcare); culturally and linguistically tailored educational materials; vascular risk factor goal tools; and Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP)19 workshops.12 Intervention participants received the BP monitors and educational materials immediately after randomization. A community advisory board offered input throughout intervention development and implementation. All care management tasks and protocols were programmed into a mobile- and web-based care management application (CommCare; Dimagi)20 that offered immediate access to patient-specific information, patient goals, real-time decision support, protocols, assessment tools, tasks, and educational materials.12 The CDSMP workshops were offered in English and Spanish by 2 CHWs at health care system and community locations convenient to participants (CHWs included A.L.M., M. Corrales, E.M.-H., M. Castro, and P.G). Each participant received a companion book in English47 or Spanish,48 and a relaxation CD in their preferred language. Care teams were encouraged to tailor the intervention to participants’ needs and assist participants in goal-setting. Participants could opt out of any aspect of the intervention.

The APCs (J.T., R.R.J., C.E., T.S.-T., B.S.) prescribed and titrated medications, emphasized medication adherence, and reinforced self-management skills. The CHWs assessed and addressed medication adherence, provided stroke education and self-management training, served as a liaison with the health care system, and offered resources or referrals to address social determinants of health.

The intervention was delivered in participants’ preferred language (English or Spanish). All CHWs were bilingual in English and Spanish. If APCs did not speak Spanish, clinic visits included an interpreter or CHW. All APCs and CHWs received extensive training.12

Process evaluations were conducted to evaluate implementation barriers. Care teams met weekly to review participants’ care plans. Additionally, study leaders (A.T., M.A.-R., and B.G.V.) met with care teams weekly to address intervention fidelity and address barriers.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes were assessed in person at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months and via telephone at 8 months.12 The primary outcome was change in mean systolic BP at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included non–high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, body mass index, waist circumference, and self-reported physical activity,21 fruit and vegetable intake,22 soda consumption,22 salt intake,23 smoking status,22 and antithrombotic medication use (for participants with ischemic stroke and TIA).

Potential mediators included health literacy,24 stroke worry,25 perceived risk of stroke,25 stroke literacy,26,27 global medication adherence,28 individual medication adherence,29 BP monitor use, self-efficacy,30 intention to quit smoking, access to care,31 patient perceptions of care (assessed using the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care33 and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems32), depression (assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 934), health care utilization,35 social support,36 and health-related quality of life (assessed using Short Form 6 Dimension37). Potential mediators for the intervention included number of clinic visits, number of home visits, and participation in CDSMP workshops.

Potential moderators included sex, self-reported race and ethnicity, country of birth (classified as US vs non-US), preferred language (English vs Spanish), education, employment prior to stroke, insurance, marital status, living situation, study site, type of cerebrovascular event (classified as ischemic stroke or TIA vs intracerebral hemorrhage), stroke severity (assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale), functional status (assessed using the modified Rankin Scale score), number of comorbidities, primary care clinician, chaos,38 competing needs,31 and acculturation.39 Chaos was measured using a brief measure of global life chaos in adults that includes questions regarding the extent to which one’s life is organized, predictable, and stable.38

Analytical Sample Size, Statistical Power, and Enrollment Sample Size

Sample size calculation and power analyses were based on systolic BP as the primary outcome. A small effect size for systolic BP (0.25 in SD units or 5.06 mm Hg) can be considered clinically meaningful in the presence of potential moderators and mediators. Power analyses were conducted for comparison of systolic BP between intervention and control arms. Using intraclass correlation of the 5 sites at 0.0085 level, SD of 20 mm Hg, 3 repeated measurements, type I error of 0.05, type II error of 0.2 (equivalent to power of 80%), 2.4 mean data points for each participant (corresponding to 30% attrition), and an autocorrelation of 0.2, the effective minimum sample size for the entire study was 261 (after adjusting for clustering effect of the 5 recruitment sites).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from October 2018 to November 2020. Comparisons of baseline characteristics between usual care and intervention arms and between participants who completed the 12-month survey vs those who did not were conducted using the 2-sample t test, χ2 test, Fisher exact test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the nature of the data.

Outcomes were compared using baseline and 12-month time points and using repeated-measures mixed-effects models that included baseline, 3-month, 8-month (only for knowledge of stroke factors and medication adherence), and 12-month data. All analyses used an intent-to-treat approach. Stratification variables (ie, site, language, stroke type) were included in repeated measures models as covariates. The key analysis was interaction of time and study arm. The bootstrap method was used to calculate 95% CIs and 2-sided P values for some variables. A 5% level of significance was used throughout.

Four sensitivity analyses were performed for the repeated measures models (eAppendix in Supplement 1); 2 of these sensitivity models included attrition weights determined by a logistic model with survey language, age, and marital status as predictor variables. In addition, an analysis of primary and secondary outcomes with an indicator variable for the ordinal categories of implementation (as a covariate) by dose was conducted. Intervention participation was classified into 5 categories a priori: (1) 3 or more clinic visits, 3 or more home visits, and 4 or more CDSMP classes; (2) 3 or more clinic visits, 3 or more home visits, and fewer than 4 CDSMP classes; (3) 2 or more clinic visits and 2 or more home visits; (4) fewer than 2 clinic visits and fewer than 2 home visits; and (5) no intervention.

For participants randomized to the intervention, a multivariable analysis evaluated the independent association of each core component (clinic visit, home visit, and CDSMP) on 12-month change in BP. Covariates included site, stroke type (ischemic stroke or TIA vs ICH) and language. Core components were dichotomized: 3 or more vs fewer than 3 clinic visits; 3 or more vs fewer than 3 home visits, and 4 or more vs fewer than 4 CDSMP classes.

Among participants with ischemic stroke, the relative risk reduction (RRR) of recurrent stroke achieved in each study arm and modified Global Outcome Score (representing the proportion of potentially preventable stroke risk reduction achieved with the level of care provided at the end of the trial, given the level of care received at the beginning of the trial) were calculated (eAppendix in Supplement 1).40

Results

Of 487 enrolled participants, the mean (SD) age was 57.1 (8.9) years; 317 participants (65.1%) were men, and 347 participants (71.3%) were Hispanic, 87 (18.3%) were Black, and 30 (6.3%) were of Asian descent (Table 1). Most participants (383 participants [78.6%]) had ischemic stroke. Although 304 participants (62.4%) had mild strokes (ie, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≤5), 310 participants (63.7%) had at least moderate disability (ie, modified Rankin Scale score ≥3). Only 135 participants (27.7%) were born in the United States; 298 of 482 participants (61.8%) had not graduated high school (Table 1). A total of 308 participants (69.1%) had government insurance (Medicaid or Medicare), and 93 participants (20.9%) were uninsured. Participants had moderate levels of life chaos, and up to one-quarter reported competing subsistence needs (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Patient Characteristics.

| Variable | Participants, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 487) | Usual care (n = 246) | Intervention (n = 241) | |

| Site | |||

| Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center | 325 (66.7) | 162 (65.9) | 163 (67.6) |

| Harbor-UCLA Medical Center | 74 (15.2) | 37 (15.0) | 37 (15.4) |

| LAC+USC Medical Center | 67 (13.8) | 34 (13.8) | 33 (13.7) |

| Olive View-UCLA Medical Center | 6 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Cedars Sinai Medical Center | 15 (3.1) | 9 (3.7) | 6 (2.5) |

| Language | |||

| English | 207 (42.5) | 106 (43.1) | 101 (41.9) |

| Spanish | 280 (57.5) | 140 (56.9) | 140 (58.1) |

| Index event | |||

| Ischemic stroke | 383 (78.6) | 193 (78.5) | 187 (77.6) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 78 (16.0) | 38 (15.4) | 43 (17.8) |

| TIA | 26 (5.3) | 15 (6.1) | 11 (4.6) |

| NIHSS | |||

| Mild (≤5) | 304 (62.4) | 159 (64.6) | 145 (60.2) |

| Moderate (6-14) | 172 (35.3) | 81 (32.9) | 91 (37.8) |

| Severe (15-24) | 11 (2.3) | 6 (2.4) | 5 (2.1) |

| Very severe (>24) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Modified Rankin Scale | |||

| No disability (0) | 30 (6.2) | 18 (7.3) | 12 (5.0) |

| Not significant (1) | 66 (13.6) | 33 (13.4) | 33 (13.7) |

| Slight (2) | 81 (16.6) | 49 (19.9) | 32 (13.3) |

| Moderate (3) | 72 (14.8) | 31 (12.6) | 41 (17.0) |

| Moderate/severe (4) | 137 (28.1) | 64 (26.0) | 73 (30.3) |

| Severe (5) | 101 (20.7) | 51 (20.7) | 50 (20.7) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 57.1 (8.9) | 57 (8.7) | 57.2 (9.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 170 (34.9) | 92 (37.4) | 78 (32.4) |

| Men | 317 (65.1) | 154 (62.6) | 163 (67.6) |

| Race | |||

| White | 335 (70.4) | 167 (69.9) | 168 (70.9) |

| Black | 87 (18.3) | 42 (17.6) | 45 (19.0) |

| Asian | 30 (6.3) | 15 (6.3) | 15 (6.3) |

| ≥1 Race | 10 (2.1) | 7 (2.9) | 3 (1.3) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 9 (1.9) | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 5 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 347 (71.3) | 177 (72.0) | 170 (70.5) |

| Born outside the United States | 352 (72.4) | 176 (71.8) | 176 (73.0) |

| Educated in the United States | 3 (3.6) | 3 (1.7) | 0 |

| Time in United States, mean (SD), y | 27.9 (12.15) | 27.3 (11.6) | 28.4 (12.7) |

| Living with ≥1 other adult | 430 (88.7) | 219 (89.4) | 211 (87.9) |

| Education | |||

| Some college | 147 (30.5) | 73 (29.9) | 74 (31.1) |

| High school graduate or GED | 37 (7.7) | 22 (9.6) | 15 (6.6) |

| Some high school but did not graduate | 115 (23.9) | 56 (24.3) | 59 (26.1) |

| ≤Eighth Grade | 183 (38.0) | 93 (38.1) | 90 (37.8) |

| Working for pay prior to stroke | 266 (55.1) | 141 (58.0) | 125 (52.1) |

| Married or in domestic partnership | 219 (45.1) | 114 (46.5) | 105 (43.6) |

| Insurance | |||

| Government | 308 (69.1) | 157 (70.4) | 151 (67.7) |

| Private insurance (with or without government) | 45 (10.1) | 21 (9.4) | 24 (10.8) |

| None | 93 (20.9) | 45 (20.2) | 48 (21.5) |

| Has primary care clinician | 231 (47.7) | 120 (49.4) | 111 (46.1) |

| Living situation | |||

| Own home | 338 (71.9) | 167 (71.4) | 171 (72.5) |

| Shelter or street | 6 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) |

| Nursing, group home, or board and care | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | 0 |

| With relative | 93 (19.8) | 46 (19.7) | 47 (19.9) |

| Room in house or hotel | 31 (6.6) | 16 (6.8) | 15 (6.4) |

Abbreviations: GED, general educational development; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Intervention and usual care groups were not significantly different with respect to baseline sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1); however, the intervention arm had a lower percentage of participants watching or reducing their salt intake and higher log CRP at baseline (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

A total of 412 participants (84.6%) completed the 12-month visit. At follow-up, there were no differences in the mean systolic BP improvement nor in the proportion achieving systolic BP control across arms, though systolic BP improved within each arm (Table 2). From baseline to 12 months, mean (SD) systolic BP improved from 143 (17) mm Hg to 133 (20) mm Hg among participants in the intervention group and from 146 (19) mm Hg to 137 (22) mm Hg among participants in the usual care group (between-group difference, −3.3 [95% CI, −14.9 to 8.8] mm Hg; P = .57) (Table 2). Controlled systolic BP (ie, <130 mm Hg) increased from 62 participants (25.7%) at baseline to 92 participants (44.7%) at 12 months in the intervention group and 53 participants (21.5%) to 89 participants (43.6%) in the usual care group).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcome | Usual care | Intervention | Differences in changes from baseline between usual care and intervention (95% CI) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Mean (SD) | Change from baseline (95% CI) | Patients, No. | Mean (SD) | Change from baseline (95% CI) | |||

| Primary | ||||||||

| SBP ≤130 mm Hg, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 53 (21.5) | 22.1 (13.9 to 30.3)a | 241 | 62 (25.7) | 18.9 (10.7 to 27.1)a | −3.3 (−14.9 to 8.8) | .57 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 89 (43.6) | 206 | 92 (44.7) | ||||

| SBP, mm Hg | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 145.7 (18.6) | −8.1 (−11.4 to −4.8)a | 241 | 143.2 (17.1) | −9.8 (−13.1 to −6.5)a | −1.7 (−6.4 to 2.9) | .46 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 136.9 (21.9) | 206 | 133.1 (20.5) | ||||

| Secondary | ||||||||

| Non-HDL, mg/dL | ||||||||

| Baseline | 201 | 95.7 (40.4) | 6.1 (−2.3 to 14.5) | 191 | 94.1 (42.3) | 2.8 (−5.2 to 10.8) | −3.3 (−14.9 to 8.3) | .57 |

| 12 mo | 197 | 104.1 (49.2) | 202 | 98.7 (47.8) | ||||

| HbA1c, % | ||||||||

| Baseline | 160 | 6.8 (1.4) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | 161 | 6.8 (1.6) | −0.3 (−0.6 to −0.1)a | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.2) | .36 |

| 12 mo | 144 | 6.6 (1.3) | 161 | 6.5 (1.2) | ||||

| Log CRP, mg/dL | ||||||||

| Baseline | 198 | −1.7 (−1.2) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2)a | 202 | −1.3 (−1.2) | −0.8 (−1.1 to −0.6)a | −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.1) | .003 |

| 12 mo | 180 | −2.1 (−1.2) | 192 | −2.2 (−1.2) | ||||

| BMI | ||||||||

| Baseline | 173 | 29.1 (5.1) | 0.4 (−0.1 to 0.8) | 163 | 29.2 (5.7) | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1)a | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.9) | .53 |

| 12 mo | 182 | 29.2 (5.01) | 186 | 29.5 (5.9) | ||||

| Physical activity, IPAQ, MET min/wk, median (IQR) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 244 | 540 (0 to 2040) | 20 (−240 to 360) | 239 | 600 (40 to 2400) | 40 (−240 to 240) | 20 (−400 to 300) | .93 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 560 (0 to 1680) | 205 | 640 (160 to 1680) | ||||

| ≥5 daily servings of fruit/vegetables, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 244 | 30 (12.3) | 1.7 (−4.2 to 7.6) | 239 | 20 (8.4) | 2.3 (−3.2 to 7.8) | 0.7 (−7.7 to 8.7) | .84 |

| 12 mo | 200 | 28 (14.0) | 206 | 22 (10.7) | ||||

| 0 daily servings of soda, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 69 (28.2) | 22.6 (15.0 to 30.2)a | 240 | 69 (28.8) | 23.2 (15.4 to 31.0)a | 0.7 (−10.6 to 12.1) | .86 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 102 (50.7) | 206 | 107 (51.9) | ||||

| Reducing or monitoring salt intake, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 134 (54.7) | 28.5 (20.8 to 36.2)a | 240 | 104 (43.3) | 43.7 (36.7 to 50.7)a | 15.4 (4.4 to 26.0) | .004 |

| 12 mo | 202 | 168 (83.2) | 208 | 181 (87.0) | ||||

| Not smoking, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 243 | 192 (79.0) | 10.2 (5.8 to 14.5) | 240 | 183 (76.3) | 11.7 (6.8 to 16.5) | 1.6 (−4.8 to 8) | .66 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 181 (89.2) | 207 | 182 (87.9) | ||||

| Using antithrombotic medication, No. (%)b | ||||||||

| Baseline | 206 | 205 (99.5) | −7.8 (−11.8 to −3.8) | 199 | 197 (99.0) | −8.4 (−12.7 to −4.0) | −0.6 (−6.7 to 5.3) | .80 |

| 12 mo | 169 | 155 (91.7) | 171 | 155 (90.6) | ||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

SI conversion factors: To convert CRP to milligrams per liter, multiply by 10; cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.029; hemoglobin to proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01.

95% confidence interval does not contain zero.

Among patients with transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke.

At 12 months, the intervention participants had a larger improvement in self-reported reduction of salt intake than usual care (between-group difference in the proportion who reported they had reduced their salt intake, 15.4 [95% CI, 4.4 to 26.0]; P = .004) (Table 2). Intervention and usual care groups did not differ on changes in the other secondary outcomes. Mean CRP decreased in both groups, but there was a larger decrease in the intervention group (control: change in log CRP, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.2] mg/dL; intervention: change, −0.8 [95% CI, −1.1 to −0.6] mg/dL; between group difference, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.7 to −0.1] mg/dL; P = .003) (to convert to milligrams per liter, multiply by 10). A total of 314 participants (64.5%) had missing waist circumference at baseline because they could not stand for measurements (eTable 3 in Supplement 1); the proportions missing were so large that the results were not considered valid. The 4 repeated measures sensitivity analyses did not differ from the main analysis for any of the primary or secondary outcome measures.

Regarding factors associated with mediating outcomes, compared with usual care, at 12 months, participants in the intervention group had a greater increase in BP monitor use, number of appointments with APCs, and statin use (for participants with ischemic stroke or TIA) (Table 3). There were no differences between groups over time for other factors associated with mediation.

Table 3. Potential Factors Associated With Mediation of Outcomes.

| Outcome | Usual Care | Intervention | Differences in changes from baseline between usual care and intervention (95% CI) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Mean (SD) | Change from baseline | Patients, No. | Mean (SD) | Change from baseline | |||

| Health literacy | ||||||||

| Confidence filling out medical forms on owna | ||||||||

| Baseline | 242 | 4 (1.3) | −1 (−1.3 to −0.8)b | 240 | 3.8 (1.5) | −0.9 (−1.2 to −0.7)b | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.5) | .44 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 2.9 (1.6) | 208 | 2.8 (1.5) | ||||

| Frequency of problems learning about medical condition owing to difficulty understanding written informationc | ||||||||

| Baseline | 237 | 3.8 (1.4) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1)b | 235 | 3.6 (1.5) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) | 0.1 (−0.2 to 0.5) | .41 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 3.5 (1.4) | 208 | 3.4 (1.4) | ||||

| Frequency of having someone help read clinic or hospital materialsc | ||||||||

| Baseline | 242 | 3.8 (1.5) | −1.1 (−1.4 to −0.8)b | 236 | 3.7 (1.6) | −1.2 (−1.5 to −0.9)b | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | .50 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 2.8 (1.6) | 208 | 2.5 (1.5) | ||||

| Frequency of having problems understanding what was told about medical conditionc | ||||||||

| Baseline | 239 | 4 (1.4) | −0.3 (−0.6 to −0.1)b | 236 | 4 (1.4) | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0) | 0 (−0.3 to 0.4) | .87 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 3.7 (1.4) | 207 | 3.6 (1.3) | ||||

| Worried about having another stroke, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 243 | 66 (27.2) | 17.7 (9.9 to 25.4)b | 240 | 68 (28.3) | 19.0 (10.7 to 27.3)b | 1.4 (−10.0 to 12.9) | .82 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 91 (44.8) | 207 | 98 (47.3) | ||||

| Believe they have a higher likelihood of having another stroke, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 243 | 140 (57.6) | −19.1 (−10.3 to −27.9)b | 240 | 126 (53.2) | −14.9 (−6.5 to −23.3)b | −4.1 (−16.5 to 8.5) | .50 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 77 (38.5) | 207 | 77 (38.3) | ||||

| Stroke literacy | ||||||||

| Knows ≥1 stroke risk factors, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 208 (84.6) | 2.7 (−3.2 to 8.6) | 241 | 196 (81.3) | 1.4 (−4.5 to 7.2) | −1.5 (−10.3 to 7.1) | .62 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 178 (87.3) | 208 | 172 (82.7) | ||||

| Knows ≥3 stroke risk factors, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 66 (26.8) | −2.8 (−10.4 to 4.7) | 241 | 55 (22.8) | 3.1 (−4.2 to 10.4) | 6.1 (−5.0,16.6) | .26 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 49 (24.0) | 208 | 54 (26.0) | ||||

| Names BP as a stroke risk factor, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 101 (41.1) | −3.8 (−11.6 to 4.0) | 241 | 91 (37.8) | 5.0 (−3.3 to 13.4) | 9.0 (−3.0 to 20.5) | .11 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 76 (37.3) | 208 | 89 (42.8) | ||||

| Medication adherence | ||||||||

| Adheres to medicationsd | ||||||||

| Baseline | 152 | 3.7 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3)b | 155 | 3.5 (1.58) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4)b | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.5) | .68 |

| 12 mo | 191 | 4.6 (0.9) | 195 | 4.6 (0.96) | ||||

| Prescribed and filled prescription for antihypertensive, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 244 | 219 (89.8) | 0.4 (−4.0 to 4.9) | 238 | 204 (85.7) | 5.2 (−0.3 to 10.6) | 4.6 (−2.2 to 11.4) | .21 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 184 (90.2) | 208 | 189 (90.9) | ||||

| Prescribed and filled prescription for statin medication, No. (%)e | ||||||||

| Baseline | 207 | 196 (94.7) | −13.4 (−19.3 to −7.5) | 196 | 179 (91.3) | −4.9 (−11.2 to 1.5) | 8.5 (0.4 to 16.9) | .04 |

| 12 mo | 171 | 139 (81.3) | 170 | 147 (86.5) | ||||

| Prescribed and filled prescription for antidepressant medication, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 244 | 38 (15.6) | −2.3 (−7.5 to 2.9) | 237 | 46 (19.4) | −4.5 (−10.3 to 1.2) | −2.1 (−9.9 to 5.7) | .56 |

| 12 mo | 204 | 27 (13.2) | 208 | 31 (14.9) | ||||

| BP monitor use | ||||||||

| Use a BP monitor at home, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 62 (25.2) | 45.2 (37.4 to 53.1)b | 240 | 63 (26.3) | 63.2 (56.2 to 70.1)b | 17.7 (7.0 to 28.1) | <.001 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 143 (70.4) | 208 | 186 (89.4) | ||||

| Use a BP monitor ≥1 time/d, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 20 (8.1) | 30.8 (23.3 to 38.2)b | 239 | 22 (9.2) | 53.3 (45.7 to 60.9)b | 22.1 (11.8 to 32.2) | <.001 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 79 (38.9) | 208 | 130 (62.5) | ||||

| Self-efficacyf | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 30.9 (7.9) | 0.5 (−0.8 to 1.8) | 239 | 31.8 (6.9) | 0.2 (−1.0 to 1.3) | −0.3 (−2.0 to 1.4) | .72 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 31.6 (8.1) | 207 | 31.3 (7.6) | ||||

| Intend to quit smoking in next month or already quit smoking, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 51 | 30 (58.8) | −2.4 (−18.1 to 13.3) | 57 | 32 (56.1) | −7.7 (−9.4 to 24.8) | 8.1 (−11.7 to 28.9) | .43 |

| 12 mo | 39 | 22 (56.4) | 47 | 30 (63.8) | ||||

| Access to care | ||||||||

| If I need hospital care, I can get admitted without any troubleg | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 1.6 (1.1) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0) | 239 | 1.6 (1.1) | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0) | 0 (−0.2 to 0.3) | .91 |

| 12 mo | 202 | 1.4 (0.9) | 208 | 1.4 (0.9) | ||||

| It is hard for me to get medical care in an emergencyh | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 3.7 (1.6) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6)b | 240 | 3.6 (1.7) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8)b | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.5) | .42 |

| 12 mo | 202 | 4 (1.5) | 206 | 4 (1.6) | ||||

| Sometimes I go without the medical care needed because it is too expensiveh | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 3 (1.7) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.4)b | 238 | 2.9 (1.8) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4)b | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | .73 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 4.2 (1.4) | 206 | 4 (1.6) | ||||

| I have easy access to the medical specialists I needg | ||||||||

| Baseline | 243 | 2.3 (1.5) | −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.2)b | 236 | 2.3 (1.5) | −0.5 (−0.8 to −0.3)b | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.3) | .67 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 1.9 (1.3) | 205 | 1.7 (1.3) | ||||

| Places where I can get medical care are very conveniently locatedg | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 1.9 (1.3) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1)b | 239 | 1.8 (1.3) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.8) | .01 |

| 12 mo | 202 | 1.6 (1.2) | 206 | 1.9 (1.4) | ||||

| I am able to get medical care whenever I need itg | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 1.8 (1.3) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2)b | 239 | 1.8 (1.3) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | 0 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .95 |

| 12 mo | 202 | 1.3 (0.9) | 207 | 1.4 (1) | ||||

| Perceptions of care (PACIC) | 96 | |||||||

| PACIC overall scorea | ||||||||

| Baseline | 96 | 2.5 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5)b | 96 | 2.6 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7)b | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .25 |

| 12 mo | 175 | 2.8 (1.1) | 186 | 3.2 (1.1) | ||||

| Patient activationa | ||||||||

| Baseline | 104 | 2.5 (1.2) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8)b | 101 | 2.7 (1.4) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.8)b | 0 (−0.5 to 0.4) | .97 |

| 12 mo | 183 | 3 (1.4) | 189 | 3.2 (1.4) | ||||

| Decision supporta | ||||||||

| Baseline | 101 | 3.1 (1.2) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.7)b | 101 | 3.2 (1.3) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9)b | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.5) | .47 |

| 12 mo | 184 | 3.5 (1.3) | 191 | 3.8 (1.2) | ||||

| Goal settinga | ||||||||

| Baseline | 101 | 2.6 (1.2) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9)b | 99 | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.9 (0.6,1.2)b | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.7) | .14 |

| 12 mo | 184 | 3.2 (1.3) | 191 | 3.6 (1.2) | ||||

| Problem solvinga | ||||||||

| Baseline | 102 | 2.4 (1.3) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0)b | 99 | 2.7 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9)b | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | .72 |

| 12 mo | 179 | 3.2 (1.4) | 189 | 3.5 (1.4) | ||||

| Follow-upa | ||||||||

| Baseline | 102 | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.7)b | 101 | 2.1 (1.1) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8)b | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | .38 |

| 12 mo | 183 | 2.2 (1.2) | 191 | 2.7 (1.2) | ||||

| Perceptions of care (adapted from CAHPS) | ||||||||

| Had a visit with any doctors, nurses, physician assistants or other PCC in the last 6 mo, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 245 | 113 (46.1) | 44 (37.1 to 50.9)b | 240 | 114 (47.5) | 42.9 (35.5 to 50.3)b | −1.1 (−10.6 to 9.1) | .79 |

| 12 mo | 203 | 183 (90.1) | 208 | 188 (90.4) | ||||

| Received from MCP the help needed to make changes in habits or lifestyle to improve health or prevent illness, answered yes, definitely, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 183 | 38 (20.8) | 27.7 (19.5 to 36.5)b | 180 | 49 (27.2) | 38.4 (29.4 to 46.7)b | 10.6 (−1.0 to 22.2) | .11 |

| 12 mo | 188 | 91 (48.4) | 192 | 126 (65.6) | ||||

| MCP spent enough time with patient, answered always/almost always/usually, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 113 | 57 (50.4) | 21.7 (10.8 to 32.0)b | 114 | 52 (45.6) | 30.9 (20.4 to 42.5)b | 9.2 (−6.5 to 24.9) | .22 |

| 12 mo | 182 | 131 (72.0) | 188 | 144 (76.6) | ||||

| MCP explained things in a way that was easy to understand, answered always/almost always/usually, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 113 | 61 (54.0) | 23.9 (13.8 to 34.7)b | 114 | 62 (54.5) | 33.6 (24.3 to 42.8)b | 9.7 (−4.8 to 23.9) | .16 |

| 12 mo | 183 | 142 (77.6) | 187 | 165 (87.8) | ||||

| MCP listened carefully to patient, answered always/almost always/usually, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 113 | 71 (62.8) | 19.8 (9.8 to 30.0)b | 112 | 69 (61.6) | 21.8 (11.7 to 31.7)b | 1.9 (−13.3 to 15.7) | .79 |

| 12 mo | 182 | 150 (82.4) | 187 | 156 (83.4) | ||||

| MCP showed respect for what patient had to say, answered always/almost always/usually, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 113 | 80 (70.8) | 15.1 (6.0 to 24.3)b | 113 | 72 (63.7) | 23.5 (13.9 to 32.6)b | 8.4 (−4.8 to 21.3) | .22 |

| 12 mo | 183 | 157 (85.8) | 187 | 163 (87.2) | ||||

| Rating of health care, No. (%)i | ||||||||

| Baseline | 113 | 87 (77.0) | 11.0 (2.6 to 19.3)b | 114 | 87 (76.3) | 16.2 (7.7 to 24.8)b | 5.3 (−6.7 to 17.2) | .37 |

| 12 mo | 183 | 161 (88.0) | 188 | 174 (92.6) | ||||

| Depression, PHQ-9 Score, mean (SD)j | ||||||||

| Baseline | 243 | 7.5 (6.1) | −2.3 (−3.2 to −1.4)b | 231 | 7.1 (5.7) | −2.4 (−3.3 to −1.6)b | −0.2 (−1.4 to 1.1) | .79 |

| 12 mo | 200 | 5.3 (5.1) | 206 | 4.7 (5.0) | ||||

| Health care utilization | ||||||||

| Visits with geriatricians, family physicians, and internal medicine physicians, mean (SD), No. in past 6 mo | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 1.4 (2.0) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.1)b | 239 | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2)b | 0.2 (−0.5 to 0.8) | .62 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 3 (2.9) | 205 | 3 (2.8) | ||||

| Visits with other types of PCC, mean (SD), No. in past 6 mo | ||||||||

| Baseline | 246 | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.3 (0 to 0.5) | 239 | 0.2 (0.9) | 1 (0.7 to 1.4)b | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.2) | .001 |

| 12 mo | 201 | 0.6 (1.6) | 205 | 1.3 (2.3) | ||||

| Quality of life, SF-6D score, mean (SD)k | ||||||||

| Baseline | 153 | 0.6 (0.1) | 0 (0 to 0) | 159 | 0.6 (0.09) | 0 (−0.1 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | .38 |

| 12 mo | 192 | 0.6 (0.09) | 203 | 0.6 (0.08) | ||||

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CAHPS, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; MCP, medical care practitioner (includes physician, nurse, and physician assistant); PACIC, Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions; PCC, primary care clinician (includes physician, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant); PHQ, patient health questionnaire; SF-6D, Short Form Six Dimension.

Scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating not at all and 5 indicating extremely.

The 95% CI does not include 0.

Scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being always and 5 being never.

Scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating never and 5 indicating all the time.

Among participants with transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke.

Range, 10 to 40, with higher score indicating more self-efficacy.

Scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strongly agree and 5 indicating strongly disagree.

Scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree.

Health care was rated on a scale of 0 (worst) to 10 (best); data here refer to patients who rated care as 6 to 10.

Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher score indicating more severe depression.

Scores range from 0 to 1, with higher score indicating better quality of life.

Subgroup analyses revealed that of 19 potential moderators, only intervention participants with severe disability and those who were working prior to the stroke had improvements in BP control compared with usual care (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Other potential moderators, including site, race, ethnicity, and preferred language, were not associated with primary (eTable 4 in Supplement 1) or secondary outcomes. While the numerical magnitude of an effect of the intervention on BP reduction was larger at the sites where BP monitors, self-management tools, and linguistically tailored materials were not provided compared with the site where these materials were provided as part of usual care, the differences in intervention impact on BP across sites were not statistically significant (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

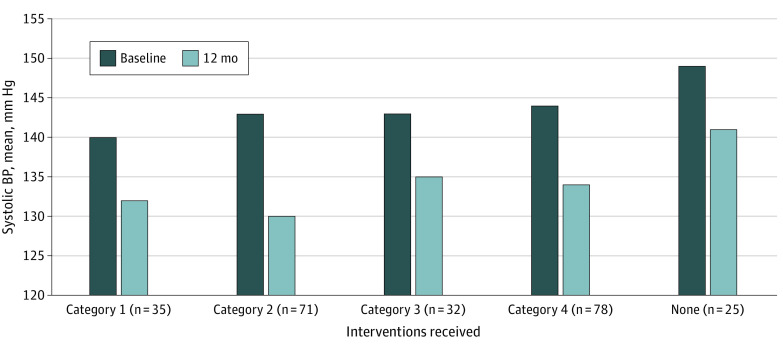

In the intervention group, a total of 35 participants (14.5%) attended 3 or more clinic visits, 3 or more home visits, and 4 or more CDSMP classes; 71 participants (29.5%) attended 3 or more clinic visits, 3 or more home visits, and fewer than 4 CDSMP classes; 32 participants (13.3%) attended 2 or more clinic visits and 2 or more home visits; and 78 participants (32.4%) attended fewer than 2 clinic visits and fewer than 2 home visits; and 25 participants (10.4%) received none of the core aspects of the intervention.

Analysis of primary and secondary outcomes by implementation category (or dose) as a covariate did not show a dose response pattern. Figure 2 shows baseline and 12-month systolic BP by dose; changes in systolic BP did not show a dose response pattern. Multivariable analysis showed that none of the 3 core components of the intervention had a unique, significant impact on BP reduction.

Figure 2. Change in Systolic Blood Pressure (BP) by Level of Participation in Intervention.

Individuals randomized to the intervention group were categorized by the extent of the intervention they received: (1) at least 3 clinic visits, at least 3 home visits, and at least 4 Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) classes; (2) at least 3 clinic visits, at least 3 home visits, and fewer than 4 CDSMP classes; (3) at least 2 clinic visits and at least 2 home visits; (4) fewer than 2 clinic visits and fewer than 2 home visits; and (5) no intervention. Changes between baseline and 12 months were not significantly different across groups.

Among participants with ischemic stroke, the estimated achieved RRR for recurrent stroke was modest at 15% (95% CI, 5% to 30%; P < .001) in the experimental group and represented one-fifth the benefit that would have been possible, given baseline risk factors and the potential impact of each risk factor intervention (modified GO score, 0.20 [95% CI, 0.06-0.38]; P = .009). Results did not differ from those in the usual care group (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial of a team-based complex intervention for improving poststroke risk factor control in a racially/ethnically diverse safety-net population, the primary outcome of systolic BP improved in both intervention and control groups, without significant differences between groups. Among secondary outcomes, participants in the intervention group had larger improvements compared with usual care in self-reported salt intake and CRP level. Of hypothesized mediators, the intervention was associated with BP self-monitoring, number of visits with APCs, and statin use. Modified GO score results suggest that trial participants in both groups averted a mean of less than one-fifth of the risk of ischemic stroke they could potentially have prevented. In both study arms, despite salutary changes in BP and smoking, when considered in concert with mild worsening of non-HDL cholesterol and antithrombotic use, the relative reduction in recurrent stroke risk was likely small.

In this complex intervention, we hypothesized that home visits, clinic visits, and CDSMP workshops were core components. While 90% of participants in the intervention group received some components, only 15% of participants received the intended full dose. Numerous factors likely affected extent of participation in intervention components. We recently found that individuals with higher numbers of clinic and home visits, moderately severe disability, and later enrollment in the study (ie, after we began offering incentives and transportation) attended more CDSMP sessions, whereas those with higher chaos scores attended fewer sessions.41 This suggests that addressing key social determinants of health may enhance participation.

There are several potential explanations for the similar BP reduction in both groups. First, by targeting numerous vascular risk factors and using collaborative goal setting, BP control may not have been prioritized. Second, only 15% of participants in the intervention group received the full intended dose. Third, there may have been contamination of usual care, as most study clinicians also treated participants randomized to usual care. Fourth, the inability to comprehensively track the care team’s adherence and adaptations to the protocols in real time limited our ability to adjust implementation strategies in an ongoing fashion. Fifth, the site that enrolled most participants routinely offered interdisciplinary education, free BP monitors, postdischarge clinics, and some self-management tools to all patients who experienced stroke. Sixth, improvements in outcomes in usual care could have been a result of a Hawthorne effect or participants’ interactions with the outcomes team (who were culturally and linguistically concordant with the participants).

Our findings were similar to other complex interventions for poststroke vascular risk factor control in Hispanic and Black individuals in urban settings.11,42,43 In a 2018 randomized clinical trial by Cheng et al11 in the same Los Angeles safety-net setting, systolic BP decreased 17 mm Hg in the intervention group and 14 mm Hg in the usual care group, but there was no significant difference between groups. A 2020 study of Black and Hispanic survivors of hypertensive stroke randomized to usual home care vs an added 30-day nurse practitioner transitional care program vs added nurse practitioner and 60-day health coach programs similarly found a 10 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP in all groups.42 A randomized clinical trial by Boden-Albala et al43 of a skills-based, culturally tailored poststroke discharge protocol in non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, or Hispanic survivors of stroke showed no difference between individuals randomized to intervention vs usual care, although a subgroup analysis revealed a 10-mm Hg greater reduction in systolic BP in Hispanic participants vs others.

Trials of APC-CHW-physician team-based interventions in nonstroke populations have shown more impressive results. These trials differed from the SUCCEED trial by directly addressing key barriers (eg, transportation and medication cost) and having additional contact with participants. For example, a randomized clinical trial by Dennison et al44 of an intensive team intervention vs information and referral for hypertensive Black men found BP improvements in both groups, with more significant changes in the intervention group. Compared with the SUCCEED trial, participants received more frequent clinic visits (≥1 visit every 2-3 months) and free transportation, BP medications, and employment guidance (ie, assistance in finding employment, to increase financial stability). The Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) study45 randomized participants with cardiovascular disease to a team intervention or enhanced usual care. At 12 months, intervention participants had greater overall improvement in lipids, BP, HbA1c, and perceptions of care quality. In contrast to the SUCCEED trial, 70% of participants in the COACH trial had more than 4 in-person visits with the NP.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including aiming to address poststroke risk factor control in a racially/ethnically diverse, high-risk population; using a theory-based behavioral intervention model; incorporating evidence-based components (eg, CCM, electronic decision support, CDSMP, and CHW home visits); adapting the intervention from lessons learned from a prior randomized clinical trial in the same setting11; framing the intervention with a conceptual model accounting for the mechanism of change anticipated based on literature and our prior experience12; community involvement in design and implementation of the intervention; allowing individual and site level variability; comprehensive intervention team training; weekly team meetings to ensure adherence to protocols and address barriers in implementation; rigorous standards for biomarker and survey collection; assessment of numerous mediators, moderators, and outcomes; and modeling the impact of multiple interventions using a recurrent stroke risk reduction tool. Many of these strengths are essential elements for developing and evaluating complex interventions.46

This study also has several limitations. First, the population enrolled and retained in the trial may not be representative of the entire patient population. Second, the sample size did not take into account variability in intervention delivery. Third, all CHWs were Hispanic and bilingual in English and Spanish, limiting cultural concordance with other ethnic groups. Fourth, by addressing numerous vascular risk factors and permitting tailoring, the impact of the intervention on the primary outcome may have been diluted. Fifth, variations in care delivery by clinician, site, and situation were incompletely characterized.

Conclusions

This randomized clinical trial did not find a difference between a complex multicomponent intervention and usual care in poststroke systolic blood pressure control in participants from safety-net settings who had experienced a recent stroke. Future studies may consider characterizing why, how, and to what extent components of the SUCCEED intervention were tailored, examining which tools and strategies were preferred for addressing each of the mediators, and assessing the extent to which evidence-based protocols were followed by the care team. Future studies may consider focusing efforts on a more select suite of interventions with the strongest evidence to reduce recurrent stroke risk; determining the effectiveness of SUCCEED if fully implemented, enhanced, or simplified; using a more racially/ethnically diverse group of APCs and CHWs; and further addressing social determinants of health.

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Usual Care at Study Sites

eTable 2. Baseline Moderators

eTable 3. Baseline Outcome Measures

eTable 4. Changes in Systolic Blood Pressure Over Time in Usual Care vs. Intervention, by Subgroup

eTable 5. Relative Risk Reduction of Recurrent Stroke in SUCCEED

eFigure. SUCCEED Conceptual Model

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hackam DG, Spence JD. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: a quantitative modeling study. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1881-1885. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng EM, Asch SM, Brook RH, et al. Suboptimal control of atherosclerotic disease risk factors after cardiac and cerebrovascular procedures. Stroke. 2007;38(3):929-934. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257310.08310.0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin AM, Lin MP, Markovic D, Ovbiagele B, Sanossian N, Towfighi A. Less than ideal. Stroke. 2018;50(1):A118022644. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim O, Ovbiagele B, Valle N, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Race-ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic risk profiles among stroke survivors with undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(12):2727-2733. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razmara A, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Patterns and predictors of blood pressure treatment, control, and outcomes among stroke survivors in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(4):857-865. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775-1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909-1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713-726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor KI, Cheng EM, Barry F, et al. Randomized trial of care management to improve Parkinson disease care quality. Neurology. 2019;92(16):e1831-e1842. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng EM, Cunningham WE, Towfighi A, et al. Efficacy of a chronic care-based intervention on secondary stroke prevention among vulnerable stroke survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(1):e003228. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Towfighi A, Cheng EM, Ayala-Rivera M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a coordinated care intervention to improve risk factor control after stroke or transient ischemic attack in the safety net: Secondary stroke prevention by uniting community and chronic care model teams early to end disparities (SUCCEED). BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0792-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. ; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee . Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boan AD, Lackland DT, Ovbiagele B. Lowering of blood pressure for recurrent stroke prevention. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2506-2513. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.003666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ovbiagele B Low-normal systolic blood pressure and secondary stroke risk. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(5):633-638. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ovbiagele B, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. ; PROFESS Investigators . Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306(19):2137-2144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin MP, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Systolic blood pressure and mortality after stroke: too low, no go? Stroke. 2015;46(5):1307-1313. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217-1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramirez M, Wu S, Ryan G, Towfighi A, Vickrey BG. Using beta-version mHealth technology for team-based care management to support stroke prevention: an assessment of utility and challenges. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(5):e94. doi: 10.2196/resprot.7106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381-1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research California health interview survey 2011-2012. Accessed January 4, 2021. http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Pages/questionnairesEnglish.aspx

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Revised December 28, 2012. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2013-BRFSS_English.pdf

- 24.Haun J, Luther S, Dodd V, Donaldson P. Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: implications for assessment selection in research and practice. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):141-159. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powers BJ, Oddone EZ, Grubber JM, Olsen MK, Bosworth HB. Perceived and actual stroke risk among men with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(4):287-294. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07797.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicol MB, Thrift AG. Knowledge of risk factors and warning signs of stroke. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(2):137-147. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.1.2.137.64085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider AT, Pancioli AM, Khoury JC, et al. Trends in community knowledge of the warning signs and risk factors for stroke. JAMA. 2003;289(3):343-346. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. ; Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) . Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255-266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227-245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439-457. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270-1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality CAHPS Clinician & Group Survey. Revised March 2019. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cg/index.html

- 33.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43(5):436-444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.RAND Corporation HCSUS baseline questionnaire. Accessed April 19, 2020. https://www.rand.org/health-care/projects/hcsus/Base.html

- 36.Wong ST, Nordstokke D, Gregorich S, Pérez-Stable EJ. Measurement of social support across women from four ethnic groups: evidence of factorial invariance. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2010;25(1):45-58. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9111-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, Roberts J, O’Hagan A. Modelling SF-6D health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. J Health Econ. 2007;26(3):597-612. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong MD, Sarkisian CA, Davis C, Kinsler J, Cunningham WE. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1286-1291. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0265-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, O’Neill AH, Ihara ES, Chae DH. Change in self-reported health status among immigrants in the United States: associations with measures of acculturation. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards A, Jackson NJ, Cheng EM, et al. Derivation and application of a tool to estimate benefits from multiple therapies that reduce recurrent stroke risk. Stroke. 2020;51(5):1563-1569. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin AM, Vickrey BG, Barry F, et al. Factors associated with participation in the chronic disease self-management program: findings from the SUCCEED Trial. Stroke. 2020;51(10):2910-2917. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldman PH, McDonald MV, Trachtenberg M, et al. Reducing hypertension in a poststroke Black and Hispanic home care population: results of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33(4):362-370. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpz148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boden-Albala B, Goldmann E, Parikh NS, et al. Efficacy of a discharge educational strategy vs standard discharge care on reduction of vascular risk in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: the DESERVE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(1):20-27. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dennison CR, Post WS, Kim MT, et al. Underserved urban African American men: hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(2):164-171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen JK, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: a randomized, controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(6):595-602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M; Medical Research Council Guidance . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lorig K, Holman H, Sobel D, et al. Living a Healthy Life With Chronic Conditions. 4th ed Bull Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez V, Hernandez-Marin M, Lorig K, et al. Tomando Control de su Salud. 4th ed Bull Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Usual Care at Study Sites

eTable 2. Baseline Moderators

eTable 3. Baseline Outcome Measures

eTable 4. Changes in Systolic Blood Pressure Over Time in Usual Care vs. Intervention, by Subgroup

eTable 5. Relative Risk Reduction of Recurrent Stroke in SUCCEED

eFigure. SUCCEED Conceptual Model

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement