Key Points

Question

Did quality of care improve in safety-net hospitals after Medicaid expansion following passage of the Affordable Care Act?

Findings

This difference-in-differences analysis in a cohort study of 811 safety-net hospitals in Medicaid expansion vs nonexpansion states found little evidence for improvement in hospital quality in the domains of patient-reported experience, health care–associated infections, readmissions, or mortality in states that expanded Medicaid compared with those in states that did not. There were modest differential increases in the adoption of electronic health records between 2012 and 2016, and in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds between 2012 and 2018.

Meaning

The results of this study suggest that safety-net hospitals may require ongoing support for quality improvement in the post-Medicaid expansion era.

Abstract

Importance

Safety-net hospitals (SNHs) operate under limited financial resources and have had challenges providing high-quality care. Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act led to improvements in hospital finances, but whether this was associated with better hospital quality, particularly among SNHs given their baseline financial constraints, remains unknown.

Objective

To compare changes in quality from 2012 to 2018 between SNHs in states that expanded Medicaid vs those in states that did not.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using a difference-in-differences analysis in a cohort study, performance on quality measures was compared between SNHs, defined as those in the highest quartile of uncompensated care in the pre-Medicaid expansion period, in expansion vs nonexpansion states, before and after the implementation of Medicaid expansion. A total of 811 SNHs were included in the analysis, with 316 in nonexpansion states and 495 in expansion states. The study was conducted from January to November 2020.

Exposures

Time-varying indicators for Medicaid expansion status.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was hospital quality measured by patient-reported experience (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey), health care–associated infections (central line–associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and surgical site infections following colon surgery) and patient outcomes (30-day mortality and readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia). Secondary outcomes included hospital financial measures (uncompensated care and operating margins), adoption of electronic health records, provision of safety-net services (enabling, linguistic/translation, and transportation services), or safety-net service lines (trauma, burn, obstetrics, neonatal intensive, and psychiatric care).

Results

In this difference-in-differences analysis of a cohort of 811 SNHs, no differential changes in patient-reported experience, health care–associated infections, readmissions, or mortality were noted, regardless of Medicaid expansion status after the Affordable Care Act. There were modest differential increases between 2012 and 2016 in the adoption of electronic health records (mean [SD]: nonexpansion states, 99.4 [7.4] vs 99.9 [3.8]; expansion states, 94.6 [22.6] vs 100.0 [2.2]; 1.7 percentage points; P = .02) and between 2012 and 2018 in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds (mean [SD]: nonexpansion states, 24.7 [36.0] vs 23.6 [39.0]; expansion states: 29.3 [42.8] vs 31.4 [44.3]; 1.4 beds; P = .02) among SNHs in expansion states, although they were not statistically significant at a threshold adjusted for multiple comparisons. In subgroup analyses comparing SNHs with higher vs lower baseline operating margins, an isolated differential improvement was noted in heart failure readmissions among SNHs with lower baseline operating margins in expansion states (mean [SD], 22.8 [2.1]; −0.53 percentage points; P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This difference-in-differences cohort study found that despite reductions in uncompensated care and improvements in operating margins, there appears to be little evidence of quality improvement among SNHs in states that expanded Medicaid compared with those in states that did not.

This cohort study compares quality measures in safety-net hospitals between states with Medicaid expansion vs nonexpansion following implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

Introduction

Safety-net hospitals (SNHs) care for a large portion of low-income, uninsured, or underinsured patients in the US.1 As a result, SNHs provide a disproportionate share of uncompensated care and are more likely to be financially challenged compared with hospitals that provide more compensated care.2 At the same time, SNHs often perform poorly on quality measures, such as hospital readmissions and patient-reported experience.3,4 Some have argued this may result from a tension between margin and mission, wherein the financial constraints of SNHs may be a key contributor to lower performance on quality measures.5

Because inadequate hospital finances have been linked to poor performance on quality metrics,6,7 some have hypothesized that improving hospital finances may be key to improving quality in SNHs.8 Even small improvements in finances may lead to quality improvements because SNHs operate under thin margins and additional resources might allow them to invest meaningfully in infrastructure and personnel needed to improve quality. Safety-net hospitals might also be motivated to dedicate additional financial resources to quality improvement to improve efficiency or expand market share.9,10,11,12 Therefore, policies that improve the financial outlook of SNHs may also improve quality.

One such policy is the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which led to reductions in uncompensated care and higher operating margins at SNHs.13,14,15 However, the outcomes associated with these financial improvements on quality and patient outcomes in SNHs are unknown. This cohort study used a difference-in-differences strategy to compare changes in quality among SNHs in states that expanded Medicaid compared with SNHs in states that did not.

Methods

Data Sources

We used the RAND Corporation Healthcare Provider Cost Reporting Information System (HCRIS) from 2010 to 2018. The HCRIS provides information on hospital finances, such as uncompensated care and operating margins, along with hospital characteristics, including number of hospital beds, ownership, and teaching status. We performed a series of exclusions based on hospital type to generate the sample (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). We also used the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey to characterize hospital resources and services, including adoption of electronic health records, provision of typical safety-net services (enabling, linguistic/translation, and transportation services), and safety-net service lines (certification as a trauma center and numbers of burn, obstetric, neonatal intensive, and psychiatric care beds).16

The study was conducted from January to November 2020. Given the use of deidentified data exclusively, the study was deemed not to require ethics board review based on the policy of the Office of Human Subjects Research Protections, National Institutes of Health, under the revised Common Rule. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We examined 3 domains of quality from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Compare database: patient-reported experience, health care–associated infections, and patient outcomes.17 Because performance on health care–associated infections and patient-reported experience is lagged by 1 year (eg, data reported in 2018 reflect care provided in 2017), we assigned data to reflect the year that care was provided. Performance on patient outcomes is similarly lagged by 1 year but calculated as 3-year averages (eg, data reported in 2018 reflect care provided from 2015 to 2017). We assigned these data to the terminal year included in the 3-year average (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

We obtained the primary exposure, a state’s Medicaid expansion status in a given year, from the Kaiser Family Foundation (eTable 2 in the Supplement).18

We collected county-level geographic and socioeconomic characteristics from the US Department of Agriculture (rural-urban commuting area codes),19 Bureau of Labor Statistics (unemployment rates),20 and Bureau of Economic Analysis (per capita income).21 We also obtained annual hospital case mix indices from the CMS impact files.

Defining SNHs

The primary definition of SNHs was based on uncompensated care provided before the ACA. We took the average annual fraction of uncompensated care (defined as total unreimbursed and uncompensated care costs as a share of operating expenses) in 2010 and 2011 for each hospital and created quartiles of these yearly averages. We defined SNHs as those in the highest quartile of baseline uncompensated care in either 2010 or 2011.

Some SNHs were missing data for 1 or more years over the analysis period (2012-2018), which may have been due to hospital closures. Because closures differentially increased in nonexpansion compared with expansion states,22 and closures may be reflective of previous quality, we characterized the frequency of missingness among SNHs in the sample and whether missingness was associated with baseline performance on quality (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Because there is no universally accepted definition of SNHs, we tested 2 alternate definitions: hospitals in the top quartile for the proportion of Medicaid patients (Medicaid inpatient days divided by total inpatient days); and hospitals in the top quartile for the allowable Medicare disproportionate share hospital percentage (eAppendix in the Supplement).2

Exposure Variable

We created a time-varying indicator for each state’s Medicaid expansion status. In states that never expanded Medicaid, this variable equaled 0 in all years. For states that expanded Medicaid on January 1 of a calendar year, this variable equaled 0 in years before expansion and 1 in the year of expansion and onward. For states that expanded Medicaid in the middle of a calendar year, following previous work,15 the variable reflected the fraction of months in the year of exposure that expansion was in effect (eg, if expansion took place in March 2015, there would be 9 months of exposure that year, and the variable would take on a value of 9/12 = 0.75 in 2015 and 1 in subsequent years) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

In main analyses, we included all states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, regardless of whether they had previously expanded their Medicaid programs or had higher baseline levels of eligibility before implementation of the ACA (eTable 3 in the Supplement). States that expanded their Medicaid programs before 2014 experienced limited coverage gains during those earlier expansions,23 followed by larger gains when they expanded Medicaid under the ACA.24 Nevertheless, we performed sensitivity analyses with these states excluded.

Primary Outcomes

We examined the quality of patient-reported experience, health care–associated infections, and patient outcomes. These measures are part of the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program from the CMS25 and represent attempts to shift hospital payment away from quantity and toward quality. Safety-net hospitals have typically had lower levels of performance on these measures.3,4,26,27

Patient experience was assessed by 8 dimensions on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey: cleanliness of hospital environment (percentage of patients reporting always clean), quietness of hospital environment (always quiet), communication with nurses (always communicated well), communication with physicians (always communicated well), responsiveness of hospital staff (always responsive), communication about medicines (always communicated well), discharge information (yes to receiving information), and the overall hospital rating (assigning a score of 9 or 10 out of 10).

Health care–associated infections were measured according to standardized infection ratios of the observed number of infections divided by the predicted number. We chose 3 types of infections based on the prevalence of reporting in preexpansion and postexpansion periods: central line–associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and surgical site infections following colon surgery.

Patient outcomes were measured using 30-day mortality and readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. These conditions were chosen, again, by prevalence of reporting among hospitals in the preexpansion and postexpansion periods. Coding definitions for pneumonia were expanded in September 201528; however, these definitions changed nationally and did not differ between expansion and nonexpansion states.

Secondary Outcomes

Using the HCRIS, we examined 2 financial outcomes: the fraction of uncompensated care and operating margins (a narrow marker of profitability based on income from patient care). Given the skewed distribution of cost data, we winsorized each measure at the first and 99th percentiles.29,30

We also examined areas of potential investment for SNHs outside of quality improvement. These factors included whether SNHs had partially or fully adopted electronic health records, offered typical safety-net services (enabling,31 linguistic/translation, and transportation services), or scaled up typical safety-net service lines (certification as a trauma center and the numbers of burn, obstetric, neonatal intensive, and psychiatric care beds).16 Previous work has reported changes in some of these outcomes following earlier Medicaid expansions.32

We evaluated hospital size (small if <100 beds, medium if 100-399 beds, and large if ≥400 beds), ownership (for-profit, not-for-profit, and government), teaching status, geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and rurality (rural, small town, large town, and urban) in the sample. We also estimated the percent of Medicaid (Medicaid facility days / total facility inpatient days ×100) and Medicare days (Medicare facility days / total facility inpatient days ×100). In addition, we examined county-level estimates of per capita income and unemployment rates.

Statistical Analysis

We compared characteristics between SNH-year observations in states that expanded Medicaid compared with those in states that did not. We then used linear regression and a difference-in-differences approach to estimate whether SNHs in expansion states had differential changes in performance on quality measures after Medicaid expansion compared with SNHs in nonexpansion states. We adjusted for hospital and year fixed effects to account for secular variation and time-invariant differences across hospitals and states during the study period, along with time-varying hospital (number of beds and case mix index) and county (per capita income and unemployment rates) covariates. Standard errors were clustered at the state level.

Our primary estimates weighted each hospital observation by hospital bed-days in 2012. We performed a stratified analysis in which we divided SNHs at the median of operating margins based on the average in 2012-2013 and categorized SNHs with lower and higher baseline operating margins. We also assessed the validity of the parallel trend assumption, using visual plots of outcomes over time stratified by Medicaid expansion status and testing formal models of preexpansion hospital-year observations with an interaction term between the exposure and the number of years elapsed since the beginning of the study period.

We then performed several additional tests and sensitivity analyses. First, to compare our findings with those from earlier work,13,14,15 we estimated the association between Medicaid expansion and uncompensated care and operating margins among SNHs. Second, we estimated the association between Medicaid expansion and SNHs’ adoption of electronic health records, provision of typical safety-net services, or ability to scale up safety-net service lines. Third, to evaluate potential differences among smaller hospitals, we estimated models in which hospitals were assigned equal weight. Fourth, to compare with other prior work,3,4,27,33,34 we examined average baseline (2012-2013) performance on quality measures between SNHs and non-SNHs. Fifth, we repeated analyses after excluding states with high preexpansion levels of Medicaid eligibility to examine the outcome in states where the ACA’s expansion represented a major change in eligibility. Sixth, we assessed for differential changes in case mix between SNHs in expansion and nonexpansion states and examined unadjusted and adjusted models to assess for potential bias after adjusting for observable characteristics. Seventh, we repeated the main analyses using 2 alternate definitions for SNHs. For all analyses, we accounted for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction, and statistical significance was determined, with P = .003 the threshold for 2-tailed, unpaired hypotheses (0.05 [corresponding to the typical threshold for statistical significance] divided by 17 [corresponding to the number of outcomes examined]). Statistical analysis was performed using Stata MP, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

We identified 811 SNHs, with 316 located in nonexpansion states and 495 in expansion states (Table 1). Among this sample, 71 SNHs (8.8%) had missingness of at least 1 hospital-year observation from 2012 to 2018 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Although more SNHs were missing data following implementation of the ACA among nonexpansion states (34 SNHs [10.8%]) than expansion states (27 SNHs [5.5%]), baseline quality was not associated with the probability of having missing data. Overall, hospital-year observations from SNHs in expansion states vs nonexpansion states were less likely to be small (1053 [31.4%] vs 1060 [50.3%]) and for-profit (508 [15.2%] vs 478 [22.7%]). In addition, SNHs in expansion states vs nonexpansion states were more often located in urban areas (2659 [79.3%] vs 1359 [64.5%]) and in counties with higher average per capita income (mean [SD], $50 914 [$19 449] vs $44 429 [$10 673]).

Table 1. Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristic | SNH-year observations, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonexpansion states (n = 2108) | Expansion states (n = 3353) | |

| Hospitals, No. | 316 | 495 |

| Size (No. of beds) | ||

| Small (<100) | 1060 (50.3) | 1053 (31.4) |

| Medium (100-399) | 866 (41.1) | 1944 (58.0) |

| Large (≥400) | 182 (8.6) | 356 (10.6) |

| Profit status | ||

| Nonprofit | 1012 (48.0) | 2265 (67.6) |

| For-profit | 478 (22.7) | 508 (15.2) |

| Government | 618 (29.3) | 580 (17.3) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 0 | 555 (16.6) |

| Midwest | 220 (10.4) | 1044 (31.1) |

| South | 1874 (88.9) | 499 (14.9) |

| West | 14 (0.7) | 1255 (37.4) |

| Teaching | 487 (23.1) | 1337 (39.9) |

| Rural-urban classification | ||

| Rural | 18 (0.9) | 7 (0.2) |

| Small town | 222 (10.5) | 146 (4.4) |

| Large town | 509 (24.1) | 541 (16.1) |

| Urban | 1359 (64.5) | 2659 (79.3) |

| % Medicaid days, mean (SD)a | 14.1 (10.2) | 15.2 (11.3) |

| % Medicare days, mean (SD)b | 32.0 (13.6) | 31.4 (12.6) |

| County-level, mean (SD) | ||

| Per capita income, $ | 44 429 (10 673) | 50 914 (19 449) |

| Unemployment rate, % | 5.5 (1.8) | 6.3 (2.3) |

Abbreviation: SNH, safety-net hospital.

Medicaid inpatient days/total inpatient days × 100.

Medicare inpatient days/total inpatient days × 100.

We present the number of SNHs in expansion and nonexpansion states reporting each outcome and the number of observations in each regression (eTable 4 in the Supplement). We also present plots of unadjusted means over time for all outcomes weighted by hospital bed-days, according to state Medicaid expansion status (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The SNHs in expansion states demonstrated a small improvement in readmissions owing to pneumonia in the preexpansion period vs SNHs in nonexpansion states (preexpansion period mean [SD], 17.8 [1.5]; coefficient for trend, −0.16; P = .09) (eFigure 3C and eTable 5 in the Supplement). In addition, SNHs in nonexpansion states showed a small preexpansion period improvement in mortality associated with acute myocardial infarction compared with those in expansion states (preexpansion period mean [SD], 14.9 [1.4]; coefficient for trend, 0.22; P = .02) (eFigure 3D and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Formal tests of preexpansion trends did not reach statistical significance (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

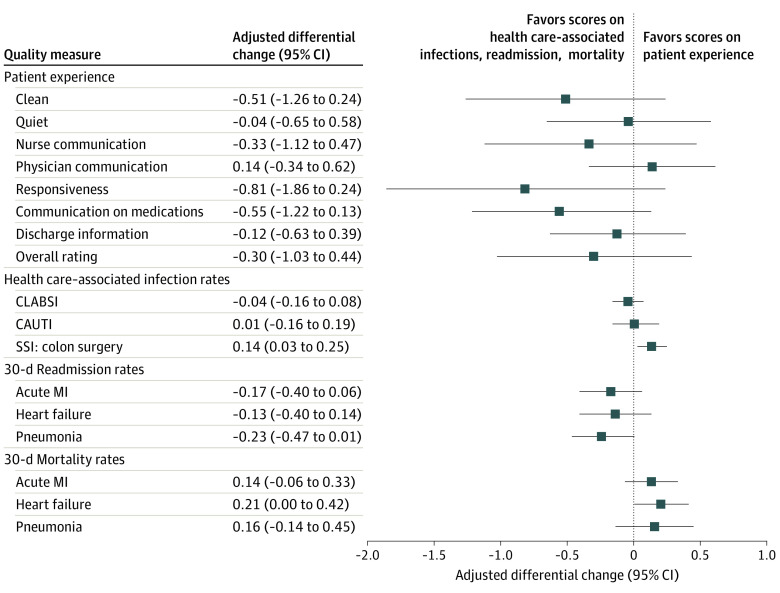

We found no statistically significant differential changes in patient-reported experience, health care–associated infections, readmissions, or mortality between SNHs in expansion and nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion (Figure). All effects were of small magnitude and not statistically significant (eTable 6 in the Supplement). In subgroup analyses comparing SNHs with relatively lower vs higher baseline operating margins, we found similar patterns except for an isolated improvement in heart failure readmissions among SNHs in expansion states with lower baseline operating margins (mean [SD], 22.8 [2.1]; −0.53 percentage points; P = .001) (Table 2).

Figure. Differential Changes in Quality Between Safety-Net Hospitals in Medicaid Expansion and Nonexpansion States.

CAUTI indicates catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; MI, myocardial infarction; SSI, surgical site infection.

Table 2. Subgroup Analyses of Safety-Net Hospitals by Lower vs Higher Baseline Operating Marginsa.

| Quality measure | Baseline operating margin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||||

| Unadjusted, mean (SD), % | Adjusted differential changeb | P value | Unadjusted, mean (SD), % | Adjusted differential changeb | P value | |

| Patient experience | ||||||

| Clean | 68.8 (6.9) | −0.08 | .89 | 70.4 (5.4) | −0.77 | .03 |

| Quiet | 56.7 (8.7) | −0.21 | .73 | 56.9 (7.6) | 0.18 | .57 |

| Nursing communication | 75.1 (5.5) | −0.18 | .76 | 77.4 (4.1) | −0.37 | .25 |

| Physician communication | 78.2 (4.3) | 0.29 | .48 | 78.5 (3.6) | 0.08 | .67 |

| Responsiveness | 60.9 (7.8) | −0.26 | .75 | 62.9 (5.8) | −1.07 | .02 |

| Communication on medications | 60.8 (5.7) | −0.41 | .45 | 62.1 (4.1) | −0.62 | .04 |

| Discharge information | 83.8 (4.2) | −0.03 | .95 | 85.6 (3.4) | −0.18 | .33 |

| Overall hospital rating | 66.0 (7.8) | 0.21 | .77 | 69.8 (6.9) | −0.61 | .09 |

| Health care-associated infections | ||||||

| CLABSI | 0.84 (0.68) | −0.10 | .29 | 0.72 (0.57) | 0.01 | .87 |

| CAUTI | 0.96 (0.72) | 0 | .99 | 0.85 (0.62) | 0.02 | .80 |

| SSI: colon surgery | 1.02 (0.84) | 0.24 | .03 | 0.87 (0.64) | 0.08 | .14 |

| Readmission | ||||||

| Acute MI | 17.2 (1.4) | −0.15 | .30 | 16.9 (1.4) | −0.20 | .22 |

| Heart failure | 22.8 (2.1) | −0.53 | .001 | 22.2 (2.0) | 0.15 | .45 |

| Pneumonia | 17.6 (1.5) | −0.13 | .17 | 17.2 (1.6) | −0.32 | .06 |

| Mortality | ||||||

| Acute MI | 14.1 (1.5) | 0.07 | .68 | 13.9 (1.5) | 0.19 | .20 |

| Heart failure | 11.4 (1.5) | −0.02 | .92 | 11.4 (1.7) | 0.36 | .02 |

| Pneumonia | 14.1 (2.8) | 0.14 | .63 | 13.9 (2.8) | 0.18 | .17 |

Abbreviations: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI, central line–associated bloodstream infection; MI, myocardial infarction; SSI, surgical site infection.

Lower: 170 hospitals in nonexpansion states; 242 in expansion states; higher: 143 hospitals in nonexpansion states; 252 in expansion states.

Adjusted differential change represents the estimated percentage point difference between safety-net hospitals in expansion states compared to those in non-expansion states since the adoption of Medicaid expansion.

Uncompensated care declined more among SNHs in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion (mean [SD], nonexpansion states, 14.2 [7.7] vs 13.0 [6.6]; expansion states, 12.3 [6.6] vs 8.8 [6.7]; 1.4 percentage points; P = .03) (eTable 7 in the Supplement), and operating margins increased more (mean [SD], nonexpansion states, −1.1 [18.3] vs −1.6 [19.7]; expansion states, 0.1 [17.0] vs 1.6 [15.8]; 2.1 percentage points; P = .04) (eTable 7 in the Supplement). The SNHs in expansion states were differentially more likely to adopt electronic health records (mean [SD], nonexpansion states, 99.4 [7.4] vs 99.9 [3.8]; expansion states, 94.6 [22.6] vs 100.0 [2.2]; 1.7 percentage points, P = .02) (eTable 8 in the Supplement) and increase the number of psychiatric care beds (mean [SD], nonexpansion states, 24.7 [36.0] vs 23.6 [39.0]; expansion states, 29.3 [42.8] vs 31.4 [44.3]; 1.4 percentage points; P = .02) (eTable 8 in the Supplement) after expansion, although neither result reached the Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance.

Models in which hospitals were given equal weight revealed similar findings for the main results (eTable 9 in the Supplement). Case mix index did not statistically significantly change between expansion and nonexpansion states during the study period (eTable 10 in the Supplement), and unadjusted models showed similar findings (eTable 11 in the Supplement). We also noted that SNHs performed less well across nearly all quality measures compared with non-SNHs at baseline, although all differences were small (eTable 12 in the Supplement). We found consistent results after excluding hospitals from states with higher levels of baseline Medicaid eligibility (eTable 13 in the Supplement). In addition, when we repeated analyses using 2 alternate SNH definitions, we found similar results (eTable 14 and eTable 15 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Safety-net hospitals play an important role in the US health care system, serving any patient, regardless of their ability to pay, and providing important health and community-based services. Despite their importance, SNHs have long been financially challenged and have had limited capacity to respond to quality improvement incentives set forth by the CMS.3,4,26,27 When Medicaid expansion led to fewer uninsured patients, it was hoped that the financial circumstances of SNHs, and consequently quality of care, would improve. However, in this national study, we found little evidence that quality improved among SNHs in states that expanded Medicaid compared with SNHs in states that did not.

Safety-net hospitals continue to face challenges in the postexpansion era, and there are several potential explanations for these findings. Safety-net hospitals serve patients at high risk for poor outcomes owing, in part, to the layers of socioeconomic challenges they face. Barriers such as structural racism, housing instability, food insecurity, limited transportation, and lower levels of health literacy or numeracy may increase the risk of readmission and other adverse outcomes.35,36,37,38 Patients at SNHs may experience longer wait times because these hospitals are often sole providers of essential, but unprofitable, services.39 Patient experience scores may be lower in SNHs owing to limited capacity of the facilities to invest in structural improvements or amenities.40 Readmission and mortality rates can be reduced by 0.2 to 1.0 percentage points with changes in staffing and discharge planning41,42; however, these investments may not be feasible for many SNHs given their baseline limited finances.

Although Medicaid expansion has had myriad positive effects on the economic and health outcomes of individuals,43,44,45 such benefits may not translate to the institutions that serve the most vulnerable populations. Although operating margins improved after Medicaid expansion, SNHs may still have financial challenges. These ongoing challenges may be the result of withdrawals of Medicaid disproportionate-share hospital payments, which traditionally served as bolstering payments for SNHs but were anticipated to be withdrawn in the postexpansion era.46 Bolstering SNHs may require more than just reducing the burden of uncompensated care, and understanding how local and state subsidies are used to support these hospitals is emerging as an area of importance. The CMS might also consider additional funding for SNHs to secure the capital required to improve quality, such as organizational infrastructure and personnel.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association between Medicaid expansion and quality among SNHs, which stood to gain more from expansion than non-SNHs. These findings are consistent with work using cardiovascular registries to suggest no changes in quality of acute myocardial infarction or heart failure care for low-income inpatients in expansion states,47,48 and other work reporting reductions in uncompensated care may not be associated with improved patient-reported experience.49 We built on previous literature with our use of nationally representative data, the inclusion of several types of quality measures, an extended follow-up period, and testing multiple definitions of SNH.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, there is no universal definition of an SNH. This lack of a formal definition remains a limitation of studies reported and for policy makers by making it difficult to design policies that support hospitals caring for the bulk of uninsured and underinsured patients.50 Nonetheless, we tested 3 definitions reported in the literature2 and found largely consistent findings. Second, our definition of quality may be limited, as we focused on measures that have improved among some hospitals after incentivization.51,52 Third, Medicaid expansion may have had multiple simultaneous downstream consequences that affect hospital care, which could have limited our ability to detect changes in quality. Safety-net hospitals may have dedicated any increase in financial resources toward supporting patient and community services in ways that are not reflected in available data. The SNHs may be increasing staffing capabilities, financing debts, or dedicating more spending toward community benefits. Our study was limited in its capacity to evaluate these other dimensions that may have also improved patient care. In addition, data on hospital finances are often incomplete and skewed, which may have prevented us from detecting changes.53 However, earlier work comparing HCRIS with internal hospital audits suggests that since 2010, HCRIS provides reliable reflections of hospitals’ financial circumstances.14,54

Conclusions

In this difference-in-differences study, we found little evidence that SNHs in expansion states improved quality compared with SNHs in nonexpansion states since Medicaid expansion. Fostering high-quality safety-net systems will require greater understanding of the factors influencing their challenging circumstances.

eFigure 1. Flow Diagram of Sample Creation

eTable 1. Measurement Dates and Year Assignments for Quality Measures

eTable 2. States Assigned as Medicaid Expansion States in Analyses

eFigure 2. Frequency of Missingness & Relationship with Baseline Quality

eAppendix. Details on Alternate Definitions for Safety-Net Hospitals

eTable 3. States with High Levels of Baseline Medicaid Eligibility Prior to 2014

eTable 4. Number of SNHs Reporting Each Outcome and Number of Observations Included in Regressions

eFigure 3. Performance

eTable 5. Regression Estimates for Parallel Pre-trends

eTable 6. Unadjusted Means (SD) for Quality Measures With Adjusted Differential Changes Between SNHs in Non-Expansion and Expansion States

eTable 7. Differential Changes in Hospital Financial Measures

eTable 8. Differential Changes in Adoption of Electronic Health Records, Safety-Net Hospital Services, and Service Lines

eTable 9. Weighted vs Unweighted Models

eTable 10. Differential Changes in Hospital Case Mix Indices After Medicaid Expansion

eTable 11. Adjusted vs Unadjusted Estimates

eTable 12. Mean Performance on Quality Measures Between SNHs and Non-SNHs in the Pre-Medicaid Expansion Period (2012-2013)

eTable 13. Regression Estimates After Removal of Expansion States With High Pre-2014 Medicaid Eligibility Levels

eTable 14. Regression Estimates After Defining Safety-Net Hospitals by Baseline Proportion of Medicaid Patients (346 SNHs in Non-Expansion States; 560 SNHs in Expansion States)

eTable 15. Regression Estimates After Defining Safety-Net Hospitals by Baseline Disproportionate Share Hospital Index (257 SNHs in Non-Expansion States; 452 SNHS in Expansion States)

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . America’s Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popescu I, Fingar KR, Cutler E, Guo J, Jiang HJ. Comparison of 3 safety-net hospital definitions and association with hospital characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198577. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee P, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient experience in safety-net hospitals: implications for improving care and value-based purchasing. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(16):1204-1210. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342-343. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.94856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazzoli GJ, Clement JP, Lindrooth RC, et al. Hospital financial condition and operational decisions related to the quality of hospital care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2):148-168. doi: 10.1177/1077558706298289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpp KG, Williams SV, Waldfogel J, Silber JH, Schwartz JS, Pauly MV. Market reform in New Jersey and the effect on mortality from acute myocardial infarction. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):515-533. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Encinosa WE, Bernard DM. Hospital finances and patient safety outcomes. Inquiry. 2005;42(1):60-72. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_42.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinleye DD, McNutt L-A, Lazariu V, McLaughlin CC. Correlation between hospital finances and quality and safety of patient care. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0219124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faber M, Bosch M, Wollersheim H, Leatherman S, Grol R. Public reporting in health care: how do consumers use quality-of-care information? a systematic review. Med Care. 2009;47(1):1-8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181808bb5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope DG. Reacting to rankings: evidence from “America’s Best Hospitals”. J Health Econ. 2009;28(6):1154-1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner RM, Norton EC, Konetzka RT, Polsky D. Do consumers respond to publicly reported quality information? evidence from nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):50-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pronovost P, Sapirstein A, Ravitz A. Improving hospital productivity as a means to reducing costs. Published March 26, 2019. Accessed October 13, 2010. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190321.822588/full/

- 13.Blavin F. Association between the 2014 Medicaid expansion and US hospital finances. JAMA. 2016;316(14):1475-1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. Uncompensated care decreased at hospitals in Medicaid expansion states but not at hospitals in nonexpansion states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1471-1479. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes JH, Buchmueller TC, Levy HG, Nikpay SS. Heterogeneous Effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion on hospital financial outcomes. Contemp Econ Policy. 2020;38(1):81-93. doi: 10.1111/coep.12428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Report to Congress on Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payments. Published February 2016. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-DSH.pdf

- 17.Hospital Compare . Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed April 1, 2018. https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital-compare

- 18.Kaiser Family Foundation . Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions, interactive map. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/

- 19.United States Department of Agriculture . Rural-urban commuting area codes. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx

- 20.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Overview of BLS statistics on unemployment. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/bls/unemployment.htm

- 21.US Bureau of Economic Analysis . Personal income by county, metro, and other areas. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.bea.gov/data/income-saving/personal-income-county-metro-and-other-areas

- 22.Lindrooth RC, Perraillon MC, Hardy RY, Tung GJ. Understanding the relationship between Medicaid expansions and hospital closures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):111-120. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommers BD, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. New evidence on the Affordable Care Act: coverage impacts of early Medicaid expansions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):78-87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith J, Medalia C. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2014. Published September 2015. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-253.pdf

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital inpatient overview. Accessed March 11, 2020. https://qualitynet.org/inpatient

- 26.Werner RM, Goldman LE, Dudley RA. Comparison of change in quality of care between safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA. 2008;299(18):2180-2187. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu HE, Wang R, Broadwell C, et al. Association between federal value-based incentive programs and health care–associated infection rates in safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e209700. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindenauer PK, Strait KM, Grady JN, Ngo CK, Johnson-DeRycke R.. Reevaluation and Re-Specification Report of the Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk Standardized Measures Following Hospitalization for Pneumonia: Pneumonia Mortality—Version 9.2, Pneumonia Readmission—Version 8.2. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilcox R. Trimming and winsorization. In: Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. American Cancer Society; 2005. doi: 10.1002/0470011815.b2a15165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conti RM, Nikpay SS, Buntin MB. Revenues and profits from Medicare patients in hospitals participating in the 340b drug discount program, 2013-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1914141. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue D, Pourat N, Chen X, et al. Enabling services improve access to care, preventive services, and satisfaction among health center patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(9):1468-1474. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedman S, Lin HZ, Simon K. Public health insurance expansions and hospital technology adoption. J Public Econ. 2015;121:117-131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilman M, Adams EK, Hockenberry JM, Milstein AS, Wilson IB, Becker ER. Safety-net hospitals more likely than other hospitals to fare poorly under Medicare’s value-based purchasing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):398-405. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajaram R, Chung JW, Kinnier CV, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with penalties in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospital-acquired condition reduction program. JAMA. 2015;314(4):375-383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey SC, Fang G, Annis IE, O’Conor R, Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Health literacy and 30-day hospital readmission after acute myocardial infarction. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e006975. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, et al. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):327-336. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196-1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swinburne M, Garfield K, Wasserman AR. Reducing hospital readmissions: addressing the impact of food security and nutrition. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45(1_suppl)(suppl):86-89. doi: 10.1177/1073110517703333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunningham P, Felland L. Environmental Scan to Identify the Major Research Questions and Metrics for Monitoring the Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Safety Net Hospitals. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuhausen K, Katz MH. Patient satisfaction and safety-net hospitals: carrots, not sticks, are a better approach. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(16):1202-1203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):444-450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Spatz ES, et al. Hospital strategies for reducing risk-standardized mortality rates in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(9):618-626. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu L KR, Mazumder B, Miller S, Wong A. The Effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions on Financial Well-being. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016. doi: 10.3386/w22170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khatana SAM, Bhatla A, Nathan AS, et al. Association of Medicaid expansion with cardiovascular mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(7):671-679. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller S, Johnson N, Wherry LR. Medicaid and mortality: new evidence from linked survey and administrative data. NBER Working Paper No. 26081; 2019.

- 46.Federal Register. Medicaid program; state disproportionate share hospital allotment reductions. Published September 25, 2019. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/09/25/2019-20731/medicaid-program-state-disproportionate-share-hospital-allotment-reductions [PubMed]

- 47.Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL, Wang TY, et al. Association of state Medicaid expansion with quality of care and outcomes for low-income patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):120-127. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Fonarow GC, et al. Association of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion with care quality and outcomes for low-income patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(7):e004729. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camilleri S, Diebold J. Hospital uncompensated care and patient experience: an instrumental variable approach. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(3):603-612. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chatterjee P, Sommers BD, Joynt Maddox KE. Essential by undefined: reimagining how policymakers identify safety-net hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2593-2595. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2030228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):486-496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):690-698. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bazzoli GJ, Chen HF, Zhao M, Lindrooth RC. Hospital financial condition and the quality of patient care. Health Econ. 2008;17(8):977-995. doi: 10.1002/hec.1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crosson F. Letter From MedPAC to CMS Regarding File Code CMS-1632-P. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flow Diagram of Sample Creation

eTable 1. Measurement Dates and Year Assignments for Quality Measures

eTable 2. States Assigned as Medicaid Expansion States in Analyses

eFigure 2. Frequency of Missingness & Relationship with Baseline Quality

eAppendix. Details on Alternate Definitions for Safety-Net Hospitals

eTable 3. States with High Levels of Baseline Medicaid Eligibility Prior to 2014

eTable 4. Number of SNHs Reporting Each Outcome and Number of Observations Included in Regressions

eFigure 3. Performance

eTable 5. Regression Estimates for Parallel Pre-trends

eTable 6. Unadjusted Means (SD) for Quality Measures With Adjusted Differential Changes Between SNHs in Non-Expansion and Expansion States

eTable 7. Differential Changes in Hospital Financial Measures

eTable 8. Differential Changes in Adoption of Electronic Health Records, Safety-Net Hospital Services, and Service Lines

eTable 9. Weighted vs Unweighted Models

eTable 10. Differential Changes in Hospital Case Mix Indices After Medicaid Expansion

eTable 11. Adjusted vs Unadjusted Estimates

eTable 12. Mean Performance on Quality Measures Between SNHs and Non-SNHs in the Pre-Medicaid Expansion Period (2012-2013)

eTable 13. Regression Estimates After Removal of Expansion States With High Pre-2014 Medicaid Eligibility Levels

eTable 14. Regression Estimates After Defining Safety-Net Hospitals by Baseline Proportion of Medicaid Patients (346 SNHs in Non-Expansion States; 560 SNHs in Expansion States)

eTable 15. Regression Estimates After Defining Safety-Net Hospitals by Baseline Disproportionate Share Hospital Index (257 SNHs in Non-Expansion States; 452 SNHS in Expansion States)