Abstract

This cohort study analyzes the association of sex steroids with cholesterol in different sex-chromosome contexts.

Mortality and morbidity from cardiovascular disease differ between men and women, and sex differences in lipid profiles may contribute to this difference. Starting at puberty, male individuals have more atherogenic cholesterol profiles, including lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, than female individuals.1 The degree to which sex hormones vs sex chromosomes and other factors contribute to this difference is unknown. The gender-affirming treatment of transgender and gender-diverse youth provides a unique opportunity to study the association of sex steroids with cholesterol in different sex-chromosome contexts.

Methods

Adolescents with no prior gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog use were recruited prior to initiating gender-affirming hormones (GAH) at 1 of 4 study sites (Boston Children’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts; Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles in Los Angeles, California; Ann & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois; and Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, California) between July 2016 and September 2018.2 The institutional review board at each site approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant or their guardian for those younger than 18 years. Laboratory and anthropometric data were collected as part of clinical care at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after beginning GAH. Obesity was defined as a baseline body mass index more than the 95th percentile for designated sex. Comparisons were made via random mixed-effects modeling using Stata version 16 (StataCorp) with a P value less than .05 considered significant. Analysis began May 2020.

Results

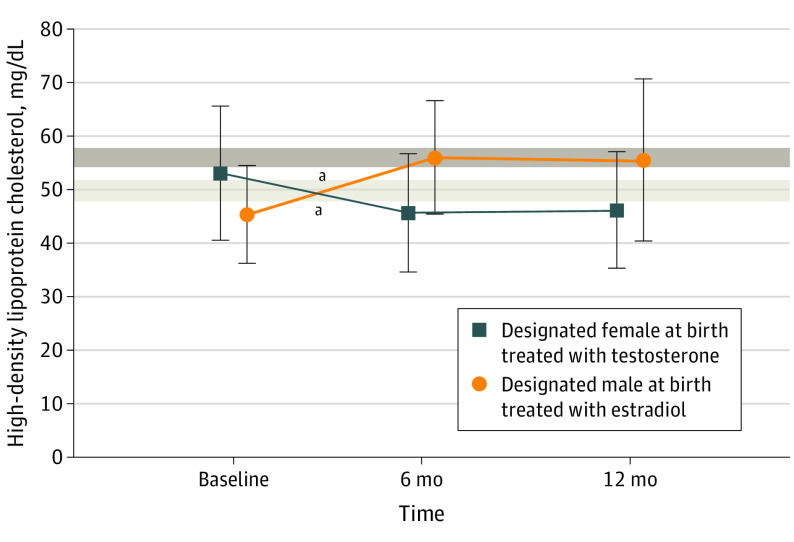

Our analysis included 269 transgender and gender-diverse youth. Eighty-three participants (31%) were designated male at birth (DMAB), and 186 (69%) were designated female at birth (DFAB). We previously reported that HDL-C levels are lower at baseline in transgender and gender-diverse youth in our cohort than in a reference adolescent cohort (Figure 1).2,3 After 6 months of estradiol treatment in participants who were DMAB, mean (SD) HDL-C levels increased by 11.2 (8.8) mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259) (95% CI, 8.6-13.8; P < .001) to fall within the range for female adolescents, and after 6 months of testosterone treatment in participants who were DFAB, decreased by a mean (SD) of 7.2 (10.1) mg/dL (95% CI, 5.3-9.1; P < .001) to fall to a level nearly identical to that of DMAB participants at baseline (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Changes in High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C) With Gender-Affirming Hormone Treatment.

SI conversion factor: To convert HDL-C to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

Bars indicate standard deviations. Shaded areas represent the 95% CI for previously published mean HDL-C levels for reference adolescent populations (light gray for boys and dark gray for girls).3 Estradiol led to an increase in HDL-C levels and testosterone led to a decrease in HDL-C levels by 6 months.

aP < .001.

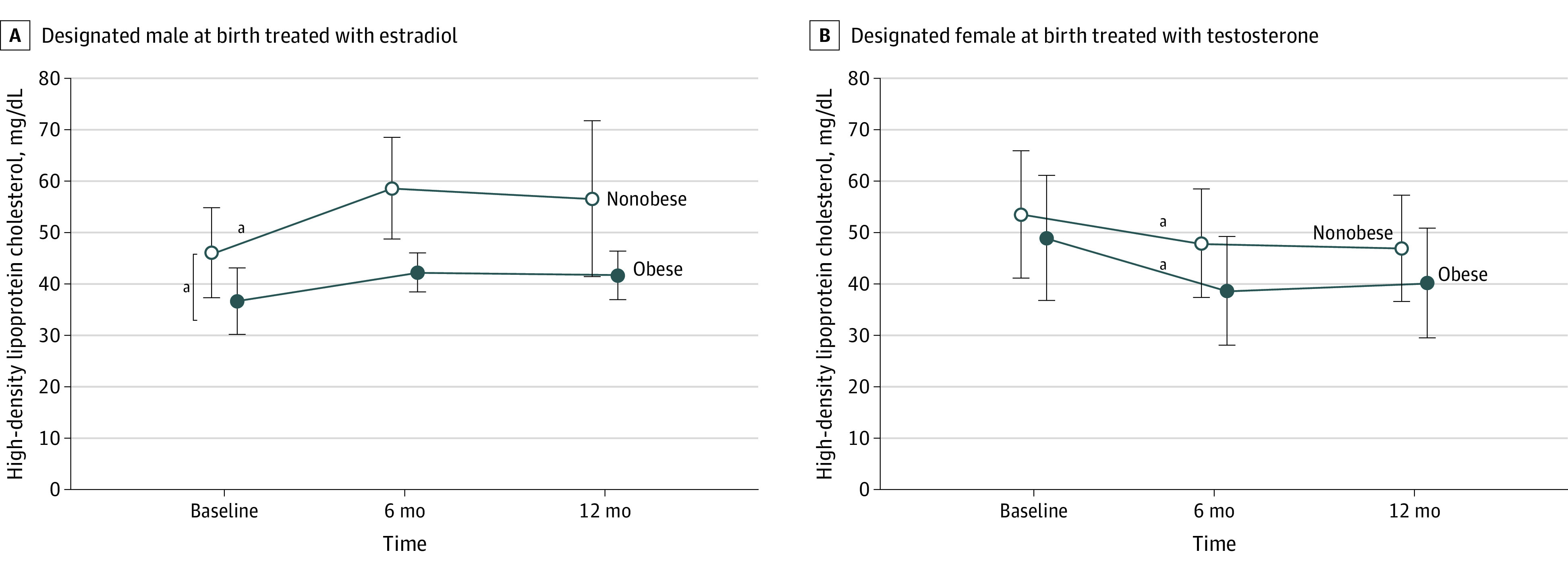

Obesity attenuated the benefit of estradiol treatment on HDL-C levels and exacerbated the association of testosterone treatment with outcomes after 6 months. Participants who were DMAB with obesity had lower HDL-C levels at baseline than participants who were DMAB without obesity (mean [SD], 36.0 [1.0] mg/dL vs 46.1 [8.8 mg/dL]; 95% CI, 35.2-36.8 vs 43.8-48.4; P = .01) and demonstrated no significant change in HDL-C levels with estradiol treatment (mean [SD], 36.0 [1.0] mg/dL vs 41.3 [4.0] mg/dL; 95% CI, 35.2-36.8 vs 37.6-45.0; P = .10). For participants who were DFAB, although baseline HDL-C levels were not significantly different between participants with and without obesity (mean [SD], 48.9 [12.2] mg/dL vs 53.5 [12.4] mg/dL; 95% CI, 44.8-53.0 vs 51.3-55.7; P = .053), the fall in HDL-C levels with testosterone was more pronounced in participants with obesity than without obesity (mean [SD], −12.1 [9.9] mg/dL vs −5.5 [9.7] mg/dL; 95% CI, −16.3 to −7.9 vs −7.7 to −3.4; P = .004) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association of Obesity With Changes in High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C).

SI conversion factor: To convert HDL-C to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259.

Open circles represent participants without obesity and closed circles represent participants with obesity (baseline body mass index >95th percentile for designated sex). Bars indicate standard deviations. Obesity attenuated the increase in HDL-C after 6 months of treatment with estradiol in participants designated male at birth. Participants designated male at birth with obesity also had lower HDL-C levels at baseline than participants designated male at birth without obesity (P = .01). The decrease in HDL-C levels after 6 months of treatment with testosterone in participants designated female at birth was more pronounced in participants with obesity. Thus, participants with obesity did not experience the benefits on HDL-C with estradiol treatment and had a more dramatic drop in HDL-C levels with testosterone treatment.

aP < .05.

Age, race, and tobacco use did not modify GAH-induced changes in HDL-C levels. GAH treatment produced no significant changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglyceride levels (data not shown).

Discussion

The decrease in HDL-C levels with testosterone is consistent with prior reports. An increase in HDL-C levels with estradiol treatment has not been consistently observed in prior studies, possibly because of differing degrees of testosterone suppression, administration in adulthood vs adolescence, and/or smaller sample sizes.4,5,6 To our knowledge, this is the first report of the modifying association of obesity with changes in HDL-C levels with GAH treatment, exacerbating the decrease in HDL-C levels with testosterone and blunting the benefit of estradiol treatment. Our results provide direct evidence for the hypothesis that changes in HDL-C levels during puberty and the differences in HDL-C levels between men and women are caused primarily by differences in sex steroids and that sex steroids work synergistically with other risk factors such as obesity.1

References

- 1.Eissa MA, Mihalopoulos NL, Holubkov R, Dai S, Labarthe DR. Changes in fasting lipids during puberty. J Pediatr. 2016;170:199-205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millington K, Schulmeister C, Finlayson C, et al. Physiological and metabolic characteristics of a cohort of transgender and gender-diverse youth in the United States . J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):376-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perak AM, Ning H, Kit BK, et al. Trends in levels of lipids and apolipoprotein B in US youths aged 6 to 19 years, 1999-2016. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1895-1905. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoffers IE, de Vries MC, Hannema SE. Physical changes, laboratory parameters, and bone mineral density during testosterone treatment in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med. 2019;16(9):1459-1468. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarin J, Pine-Twaddell E, Trotman G, et al. Cross-sex hormones and metabolic parameters in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20163173. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vita R, Settineri S, Liotta M, Benvenga S, Trimarchi F. Changes in hormonal and metabolic parameters in transgender subjects on cross-sex hormone therapy: a cohort study. Maturitas. 2018;107:92-96. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]