Abstract

The specific cytotoxic effect of nanoparticles on tumor cells may be used in future antitumor clinical applications. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been reported to have potent cytotoxic effect, but the mechanism is unclear. Here, AgNPs were synthesized, and the particle average size was 63.1 ± 8.3 nm and showed a nearly circular shape, which were determined by transmission electron microscopy and field emission scanning electron microscopy. The selected area electron diffraction patterns showed that the nanoparticles were crystalline. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectrum proved that silver is the main component of nanoparticles. The AgNPs showed potent cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells, no matter whether they were tamoxifen sensitive or resistant. Next, we found that a long noncoding RNA, XLOC_006390, was decreased in AgNPs-treated breast cancer cells, coupled to inhibited cell proliferation, altered cell cycle and apoptotic phenotype. Downstream of AgNPs, XLOC_006390 was recognized to target miR-338-3p and modulate the SOX4 expression. This signaling pathway also mediates the AgNPs function of sensitizing tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells to tamoxifen. These results provide a new clue for the antitumor mechanism of AgNPs, and a new way for drug development by using AgNPs.

Keywords: silver nanoparticles, breast cancer, lncRNA, microarray, cytotoxicity

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women worldwide and one of the leading causes of cancer death [1]. Chemoresistance induced by chemotherapy has been reported more and more and became one of the most important factors of chemotherapy failure [2]. Breast cancer is categorized into three major subtypes based on the presence or absence of molecular markers for estrogen receptors (ER) and human epidermal growth factor 2 (ERBB2; formerly HER2): ER positive/ERBB2 negative (70% of patients), ERBB2 positive (15–20%) and triple negative (tumors lacking all three standard molecular markers; 15%) [3]. ER-positive cases can be treated with tamoxifen by targeting the ER, and it is reported that tamoxifen can significantly reduce the recurrence rate by 40% and the mortality rate by 30% in the ER-positive breast cancer patients [4]. However, about a quarter of breast cancer patients have tamoxifen resistance, and there is a great risk of recurrence in these patients, which brings great challenges to the clinical treatment of breast cancer [5]. Therefore, it is urgent to develop novel effective prevention agents that are expected to deal with drug-resistant breast cancers, improve quality of life and decrease the frequency of invasive surveillance procedures.

Due to the unique physical and chemical properties, like small size, high specific surface area, high reactivity, etc., silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) is increasingly used in various fields such as medical treatment, food, health care, consumption and industry [6]. Recently, silver (Ag) or AgNPs have been reported to be potential anticancer drugs or adjuvants, but the molecular mechanism is not clear. According to the literature, AgNPs may induce cancer cells apoptosis by activating p53, so as to achieve the antitumor effect [7]. However, the latest literature shows that AgNPs can defeat both p53-positive and p53-negative cancer cells [8]. These results suggest that the functions of AgNPs are complex and need further study.

In recent years, many studies have shown that noncoding RNA, including long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), is the main regulator of many diseases, including infections [9], autoimmune diseases [10] and cancer [11]. Sporadic reports indicated that AgNPs can change the expression of many miRNAs, which may be one of the important ways to regulate the signal pathway related to some diseases [12]. We speculate that there may be lncRNAs regulated by AgNPs, and they might play a key role in mediating the antitumor function of AgNPs. With the development of transcriptome determination, like RNA sequencing and microarray assay, it is possible to determine the lncRNAs as a whole of the cells. Therefore, we plan to test AgNPs’ cytotoxical effect on breast cancer cells and explore its molecular mechanism through lncRNAs determination. Preliminary experiments have confirmed that AgNPs have significant cytotoxic effects on breast cancer cell lines and primary breast cancer cells and can overcome the chemoresistance of tamoxifen resistances. Furthermore, lncRNAs-based molecular biological experiments have shown that these functions are achieved partly by lncRNA XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p axis regulation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

We purchased all organic solvents, as well as silver nitrate (≥99.0%), tannin, sodium citrate, octadecylamine and Ag dispersion (40 nm particle size) from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All of these chemicals are not further purified before used. Paraffin was purchased from Marco Viti (Mozzate, Italy). Colloidal nanoparticles (NPs) were obtained from Atena Srl (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

Chemical synthesis and characterization of NPs

The synthesis of AgNPs was based on previous reports [13]. We prepared 100 ml of aqueous solution containing 5 mM sodium citrate and 0.025 mM tannic acid, boiled the solution for 15 min, and then quickly added 1 ml of silver nitrate aqueous solution (25 mM) with syringe under intense stirring (750 rpm). The solution turned yellow immediately, then heated for 1 h, cooled and stirred overnight at room temperature.

The formation of AgNPs was evaluated by ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy. The characteristic absorption peak of AgNPs corresponds to the plasma resonance band. The size and morphology of AgNPs were studied by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Zeiss EM10C). Totally, 300 particles were measured in random fields of view to calculate the mean particles sizes. The energy-dispersive X-ray (EDS) analysis analyzer (JSM-7600F, JEOL, Japan) was used for product element analysis. X-ray diffraction analysis (Xpert pro, PANalytical, Holland) was performed to investigate the crystalline phase of synthesized AgNPs. The obtained AgNPs were centrifuged at 4°C at 25 000 × g and washed twice for further purification. Then, the purified AgNPs were suspended in 1 mM sodium citrate solution or 0.3 mM phosphate buffer, with a pH value of 7.2, for subsequent use. The concentrations of AgNPs were calculated by the content of metallic Ag contained in AgNPs, which were determined by measuring the absorbance at 440 nm in UV–Vis spectrophotometer with standard curve method. AgNPs (item no: Ag010006; concentration: 0.1 mg/ml; size: 60 nm) purchased from Shanghai So-Fe Biomedicine Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China) was used as standard. The standard curve was established as following: the standard suspension was diluted by deionized water into 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 mg/L. The absorbance of standard samples with different concentrations was measured at 440 nm, and the standard curve was drawn based on the correlation between absorbance values and AgNPs concentration.

Cell lines culture

MCF7, T47D and MDA-MB-231 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and were used in this study. MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, USA), 0.01 mg/ml human recombinant insulin (Sigma, USA), 100 IU/ml penicillin (Sigma, USA) and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, USA). T47D cells were maintained in Roswell park memorial institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, USA), 100 IU/ml penicillin (Sigma, USA) and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, USA).

Acquisition of tamoxifen-resistant cells

Acquisition of tamoxifen-resistant cells referred to the published literature [5]. Briefly, MCF7 or T47D cells were seeded in six-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 containing 5% charcoal-stripped steroid-depleted FBS (Hyclone, USA) for another 24 h, and then 0.1 μM 4-OH tamoxifen was added to the medium. Finally, the concentration of 4-OH tamoxifen was gradually increased up to 1 μM. When the growth of the cells cannot be inhibited with 1 μM 4-OH tamoxifen, the tamoxifen-resistant cell lines were established and were named MCF7-Re and T47D-Re, respectively.

Isolating the primary breast cancer cells

The breast cancer patients included in this study were from the Second Affiliated Hospital and First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Totally, 64 cases of breast cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues were obtained from these 64 breast cancer patients by surgery, and then the primary single-cell suspensions of tumor and normal cells were extracted from them using explant cultures according to the previous reports [14]. Briefly, the tumor samples were washed with PBS containing 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Then, in the cell culture room, the sample was cut into small pieces of about 1 mm thickness with scissors in sterile DMEM/F-12 1:1 (V:V) medium, inoculated in flasks. The DMEM/F-12 medium, supplemented with FBS, Pen/Strep, glutamine, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, bovine serum albumin, cholera toxin, hydrocortisone, insulin, epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract, was exchanged for the cells every day. During this culture phase, the explants were removed by simply shaking and washing the flask. After 2 weeks, the tissue was removed and the dish was washed with PBS to remove dead cells and tissue residues. In order to produce clumps, trypsinization was shortened and performed at room temperature; the cells were scraped off with a cell scraper. The cultures were scraped off with a cell scraper, passaged as clumps of about 5–10 cells after several weeks when the circumference of the islands stopped growing. Then, the cells were cultured at 37°C and passed on every 3–4 days.

MTT assay

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used to determine the AgNPs cytotoxic effects against different types of cancer cells. Briefly, after counting the cells to be measured, we inoculated the cells into 96-well plates with 10 000 cells/well for 24 h, and then treated the cells with AgNPs at certain concentrations for 24 h. The same volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as negative control. Subsequently, we treated the cells with MTT solution for 3 h, added DMSO and then placed the cells for 15 min. Finally, ELISA microplate reader (DYNEX, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 570 nm (optical density (OD) value). The cell number was calculated by the corresponding OD value through the standard curve. The percent cells survival rate of AgNPs treatment was calculated by the following equation:

|

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were cultured in serum starvation medium at G0 stage for 3 days, and then the medium was replaced by a medium containing 10% FBS for culture. Cell cycle progression is monitored by detecting DNA content [10]. Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized and fixed in 70% methanol for 2 h at −20°C. Subsequently, cells were precipitated (5 min of centrifugation at 500 × g at 4°C in a Sigma 6 K15 centrifuge), washed with PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 40 U of RNase A per milliliter and 40 μg of propidium iodide (PI) per milliliter. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, DNA flow cytometric analysis was performed with an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter). For quantification, we used Multicycle AV software (Phoenix Flow Systems).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay

To obtain the total RNA, the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) was used. The quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) detection reagent for miRNA and messenger RNA (mRNA) were TaqMan™ MicroRNA Assay Kit and PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit, which were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA) and Takara (Shiga, Japan), respectively. The instrument used to perform qRT-PCR analyses was iQ5 real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The following parameters were used for the reverse transcription action for mRNA according to the previous description [9]: 65°C for 5 min, 37°C for 15 min and finally 98°C for 5 min. The following parameters were used for the subsequent PCR reaction: 95°C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 5 s and finally 72°C for 30 s. Primer sequences for all the targets were described as following: GAPDH: 5′ATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCA3′ (forward) and 5′GTCGCTGTTGAAGTCAGAGGA3′ (reverse); XLOC_006390: 5′ TCCTTTGAATCCCTGAGAACTGAAC3′ (forward) and 5′ ACCTTCCTTCCCACTGGACCTTC3′ (reverse); P21: 5′ GTGAAAACAGAGCGAGAGAGATG3′ (forward) and 5′ CAGGGGTACAGTGCTAAAGGC3′ (reverse); cyclin D1: 5′ GCTGCGAAGTGGAAACCATC3′ (forward) and 5′ CCTCCTTCTGCACACATTTGAA3′ (reverse); BAX: 5′ TCCACCAAGAAGCTGAGCGAG3′ (forward) and 5′GTCCAGCCCATGATGGTTCT3′ (reverse); BCL-2: 5′ TTCTTTGAGTTCGGTGGGGTC3′ (forward) and 5′ TGCATATTTGTTTGGGGCAGG3′ (reverse); γH2AX: 5′ CGGCAGTGCTGGAGTACCTCA3′ (forward) and 5′ AGCTCCTGGTCGTTGCGGATG3′ (reverse); SOX4: 5′ AGCGACAAGATCCCTTTCATTC3′ (forward) and 5′ CGTTGCCGGACTTCACCTT3′ (reverse).

Cell transfection

The XLOC_006390 overexpressing (XLOC_006390 OV) plasmid were constructed and kept in our laboratory. Shanghai GenePharma Co. Ltd provides oligonucleotides (Shanghai, China) for overexpression (mimics), inhibition (inhibitor) and control (miR-control) of miR-338-3p. The cell transfection reagent was Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Waltham, MA, USA). Referring to the instructions, cells were transfected with these oligonucleotides or XLOC_006390 OV plasmid at 50 nM to construct the cell environment of miR-338-3p or XLOC_006390 overexpression or inhibition.

Cell apoptosis analysis

Apoptotic cells were detected by Annexin V-Fluos Staining Kit (Roche-Boehringer) according to the previous report [15]. Briefly, the cells to be tested were incubated with annexin V and PI for 15 min and then were analysed with 488 nm excitation and 515 nm annexin V detection on the flow cytometer, and PI detection was performed with a filter with a wavelength >600 nm. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter). For quantification, we used Multicycle AV software (Phoenix Flow Systems).

LncRNA microarray

The RiboArray lncRNA DETECT Human Array were synthesized by Ribobio (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China). Subsequently, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into antisense RNA (aRNA), and then 6 μg of aRNA was labeled with Cy3 fluorophore by Amino Allyl MessageAmpTM II aRNA Kit (Invitrogen, USA). Microarrays with labeled samples were hybridized at 40°C for overnight and washed using buffers recommended in the manufacturer’s protocol. Slides were scanned using a Genepix 4000B laser scanner (Axon Instruments, USA) and images were analysed using Genepix Pro 7.0 software (Axon Instruments, USA). Signals that were <1.5 times stronger than the background were removed.

Luciferase reporter assay

For the luciferase report system, the wild-type or mutant 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of SOX4 mRNA were synthesized and inserted into PGL3 basic reporter vectors (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Luciferase activity assay was performed according to the instruction manual (Promega Company).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyse the experimental data. Each experiment was repeated three times and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The differences between the two groups were statistically analysed by two-tailed t-test. P value <0.05 is considered to have statistical difference.

Results

Identification of AgNPs

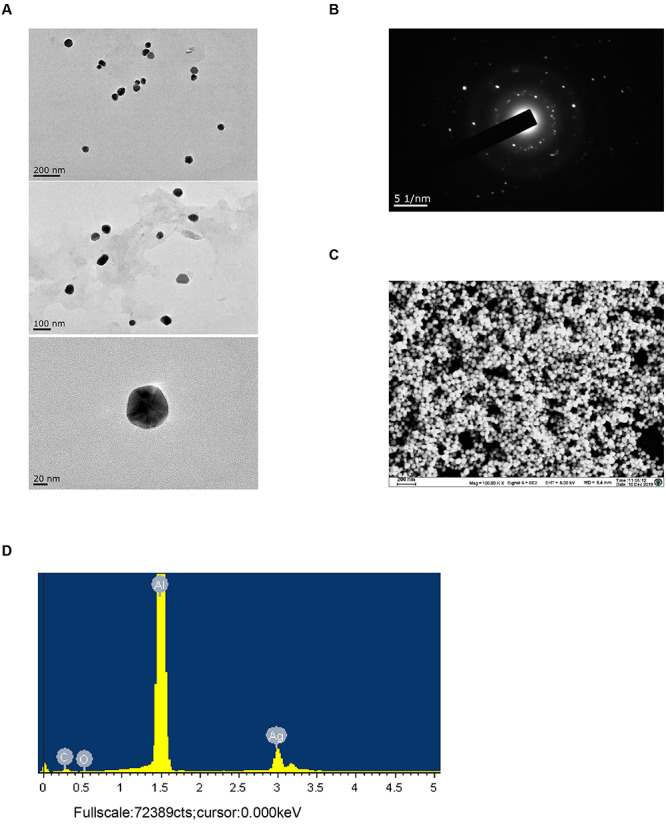

TEM analysis determined the morphological structure of AgNPs (Fig. 1A), finding that the particle average size was 63.1 ± 8.3 nm, with a polydispersity index value of 0.37 ± 0.05, indicating that AgNPs showed homogeneous size distribution. The results of selected area electron diffraction showed that the synthesized AgNPs were crystalline (Fig. 1B). The results of field emission scanning electron microscopy showed that the surface of AgNPs was smooth and varied (Fig. 1C). The EDS spectrum of the synthesized AgNPs has presented an intense peak at 1.5 keV, signifying the entire composition of Ag in the developed AgNPs (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Identification of AgNPs. (A) TEM images of synthesized AgNPs. Up: scale is 200 nm; middle: scale is 100 nm; down: scale is 20 nm. (B) The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of synthesized AgNPs. (C) Field emission scanning electron microscopy image of synthesized AgNPs. (D) EDS pattern of synthesized AgNPs.

Cytotoxicities of AgNPs against the breast cancer cells

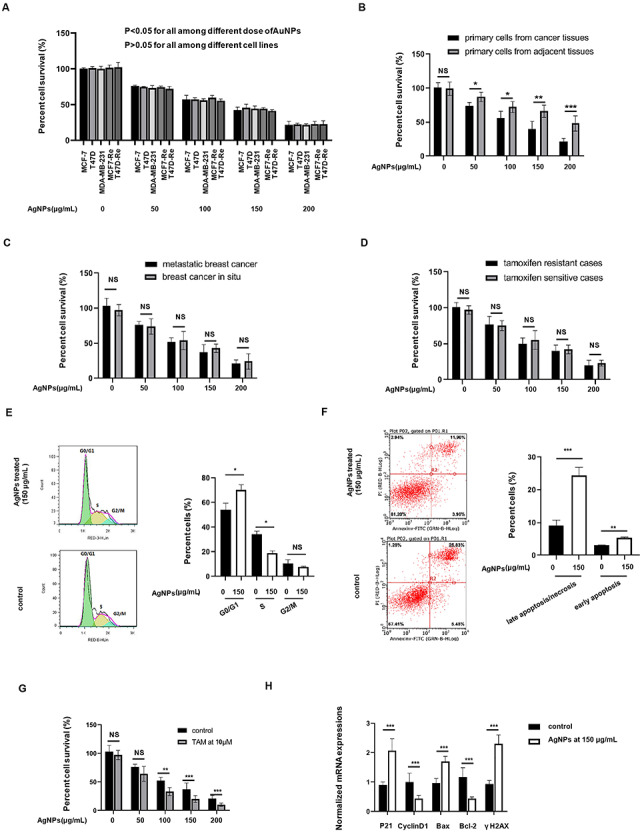

Next, we found that the synthesized AgNPs have potent cytotoxicities in a concentration-dependent manner on both early-stage breast cancer cell line (MCF7) and metastatic breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), regardless of their tamoxifen sensitive (MCF7 and T47D) or resistant (MCF7-Re and T47D-Re) patterns (IC50s were about 150 μg/ml for all). Subsequently, the cytotoxicities of AgNPs were further studied on primary cells isolated from the breast cancer tissues (primary breast cancer cells) and matched adjacent tissues (primary normal cells) of 64 patients. The clinical characteristics of these patients were summarized in Table 1. Totally, 21 cases were metastatic breast cancer and 43 were in situ breast cancer. There were 14 cases with tamoxifen-resistant patterns and 50 cases were tamoxifen sensitive. Data indicated that the cytotoxicities of AgNPs on primary breast cancer cells were stronger than that on primary normal cells (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, there was no difference in the cytotoxicity of AgNPs to cancer cells in situ and metastasis (Fig. 2C) and to tamoxifen resistant and sensitive cases (Fig. 2D).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic details of breast tumors used in this study

| Clinical parameter | Numbers |

|---|---|

| Patients included in this study | 64 |

| Age (years) | 48.7 ± 16.6 |

| Tumor receptor | |

| ER | 23 |

| PR | 19 |

| Her2 | 5 |

| Ki67 | 17 |

| Tumor grade | |

| I or II | 27 |

| III or IV | 39 |

| Metastasis | |

| Breast cancer in situ | 43 |

| Metastatic breast cancer | 21 |

| Tamoxifen-resistant patterns | |

| Sensitive | 50 |

| Resistant | 14 |

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic effects of AgNPs against different cancer cells in vitro. (A) Five breast cancer cells were treated with AgNPs at concentration ranges from 50 to 200 μg/ml for 24 h, and then the percent cell survival (%) were determined in comparing with the control cells without AgNPs treatment. (B) Patients-derived breast cancer cells and the adjacent normal cells were treated with AgNPs at concentration ranges from 50 to 200 μg/ml for 24 h, and then the percent cell survival (%) were determined in comparing with the control cells without AgNPs treatment. (C) Comparing the percent cell survival (%) described in (B) between tamoxifen resistant and sensitive breast cancer cells. (D) Comparing the percent cell survival (%) described in (B) between metastatic and in situ breast cancer cells. (E and F) MCF7 were treated with AgNPs at 150 μg/ml or not for 24 h, and the (E) cell cycle analysis and (F) apoptosis assay were performed. (G) MCF7-Re cells (tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells) were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM) at 10 μM or not, together with AgNPs at concentration ranges from 50 to 200 μg/ml or not for 24 h, and then the percent cell survival (%) were determined. (H) Determination of the mRNA expressions of the targets involved in the cell cycles (P21 and cyclin D1), apoptosis progressions (Bax and BCL-2) and DNA damages (γH2AX) in the cells described in (E and F) by qRT-PCR assay.

We further explored the regulatory role of AgNPs on the cancer cell functions. Low concentration of AgNPs has weak cytotoxicity on cells, whereas high concentration of AgNPs can cause nonspecific changes of cell cycle because of too few cells. Therefore, 150 μg/ml AgNPs (IC50s) was used for the follow-up explorations. We found that AgNPs treatment at 150 μg/ml could induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest (Fig. 2E) and promote both early apoptosis and late apoptosis/necrosis rate (Fig. 2F) significantly in MCF7 cells. In addition, without AgNPs treatment, the MCF7-Re did not show any decrease in survival when treated with up to 10 μM of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM), whereas with no <100 μg/ml AgNPs treatment, the MCF7-Re showed a significant decrease in survival when treated with 10 μM of 4-hydroxytamoxifen, indicating that AgNPs processing can weaken the tamoxifen-resistant patterns in breast cancer cells (Fig. 2G). It was reported that cell cycle distribution and apoptosis process-related DNA damage archive the main reason for tamoxifen resistance [16]. Interestingly, our qRT-PCR assay demonstrated that many of targets involved in the cell cycles (P21 and cyclin D1), apoptosis progressions (Bax and BCL-2) and DNA damages (γH2AX) were regulated by 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment (Fig. 2H).

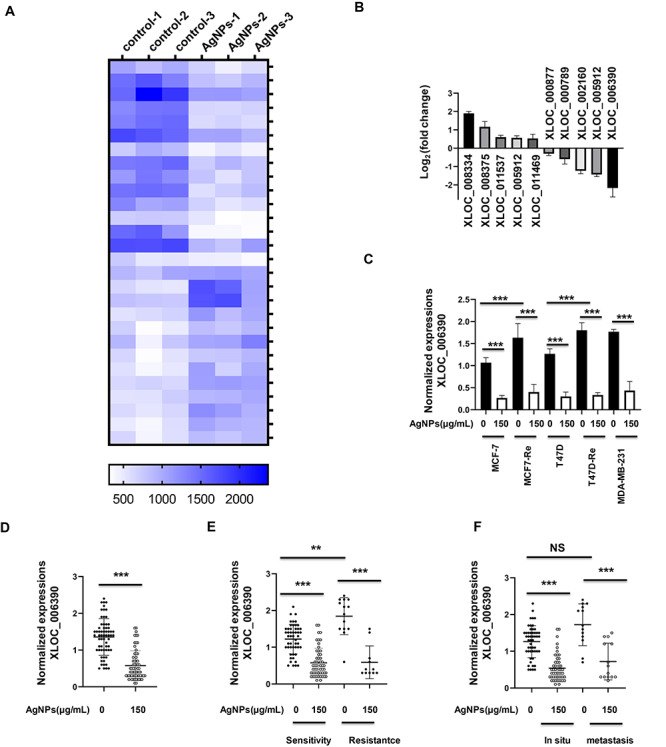

Identification of key lncRNAs involved in the cytotoxic effect of AgNPs against breast cancer cells

We next used 150 μg/ml AgNPs-treated MCF7 cells and nontreated controls to investigate the global characteristics of AgNPs-associated lncRNAs. With a cut off line of >1.5-fold and P ≤ 0.001, totally 15 downregulated and 13 upregulated lncRNAs were identified under 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment (Fig. 3A). Among them, XLOC_006390 was the most obvious decreased target in the microarray results (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, qRT-PCR validations demonstrated that the XLOC_006390 expressions were higher in MCF7-Re and T47D-Re cells, comparing with the MCF7 and T47D cells, respectively, and 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment decreased the XLOC_006390 expressions of all the tested cells (Fig. 3C). Also, AgNPs treatment can reduce the XLOC_006390 levels in all the primary breast cancer cells (Fig. 3D), including in situ and metastatic cancer cells (Fig. 3E), regardless of tamoxifen resistant or not patterns (Fig. 3F). This modulation of AgNPs to XLOC_006390 made us ask whether XLOC_006390 mediate the AgNPs functions.

Figure 3.

Microarray analyses reveal a role of AgNPs in lncRNAs expressions. (A) MCF7 cells were treated with AgNPs at 150 μg/ml for 24 h, and then the total RNA was then collected for microarray analyses. The differentially expressed lncRNAs between AgNPs treatment group and control group were clustered by heatmap (P < 0.001 included). (B) Fold change of the differentially expressed lncRNAs between AgNPs treatment group and control group described in (A). (C) Confirmation of XLOC_006390 expression in five breast cancer cell lines after 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment for 24 h by qRT-PCR analysis. (D) Confirmation of XLOC_006390 expression in patients-derived breast cancer cells after 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment for 24 h by qRT-PCR analysis. (E) Confirmation of XLOC_006390 expression in tamoxifen resistant and sensitive breast cancer cells described in (D). (F) Confirmation of XLOC_006390 expression in metastatic and in situ breast cancer cells described in (D).

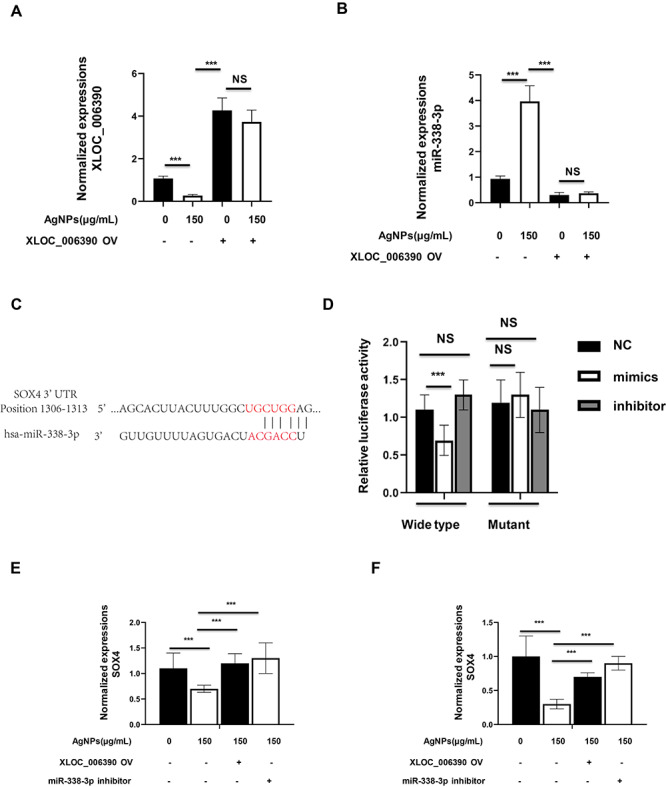

AgNPs-regulated miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis through decreasing the XLOC_006390 expressions in breast cancer cells

Recent studies have proposed that an lncRNA may participate in the competing endogenouse RNA (ceRNA) regulatory network and therefore regulate some miRNAs [17]. Referring to the DIANA-LncBase v2 and previous report, we found that XLOC_006390 formed complementary base pairing with miR-338-3p [16, 17]. In this study, when the MCF7 cells were treated with 150 μg/ml AgNPs, the miR-338-3p would be induced, together with XLOC_006390 decreased, whereas the miR-338-3p expressions could not be altered by AgNPs in XLOC_006390-OV-transfected MCF7 cells (Fig. 4A and B). Through the analysis in Targetscan website (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), we found that SOX4 was a potential target of miR-338-3p, and their binding sites were shown in Fig. 4C. Next, we confirmed this binding using a luciferase report system, which showed that miR-338-3p mimics significantly inhibited the luciferase activity in HEK293 cells, which were containing the wild-type 3′UTR of SOX4, whereas the luciferase activity in those with the mutant 3′UTR of SOX4 was not influenced (Fig. 4D). Meanwhile, 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment significantly decreased mRNA expression of SOX4 in both MCF7 and MCF7-Re cells, whereas this regulation was reversed when XLOC_006390-OV was transfected (Fig. 4E and F). The above results demonstrated that AgNPs-regulated miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis through decreasing the XLOC_006390 expressions in breast cancer cells.

Figure 4.

AgNPs-regulated miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis through decreasing the XLOC_006390 expressions in breast cancer cells. (A and B) The MCF7 cells were transfected with or without XLOC_006390 overexpressing plasmid (XLOC_006390 OV), together with 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment for 24 h, and then the (A) XLOC_006390 and (B) miR-338-3p expressions were determined by qRT-PCR assay. (C and D) Luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that SOX4 is a direct target of 338-3p. (C) Sequences of the binding sites between miR-338-3p and 3′UTR of SOX4. (D) Bars show the ratio of Renilla activity/Firefly activity in HEK293 cells 24 h after cotransfection of luciferase vectors containing wild-type or mutant 3′UTR of SOX4 and miR-338-3p mimics, inhibitor or mimics negative control, respectively. (E and F) The (E) MCF7 cells and (F) MCF7-Re cells were transfected with or without XLOC_006390 OV plasmid, or with or without miR-338-3p inhibitor, together with 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment for 24 h, and then the SOX4 mRNA expressions were determined by qRT-PCR assay.

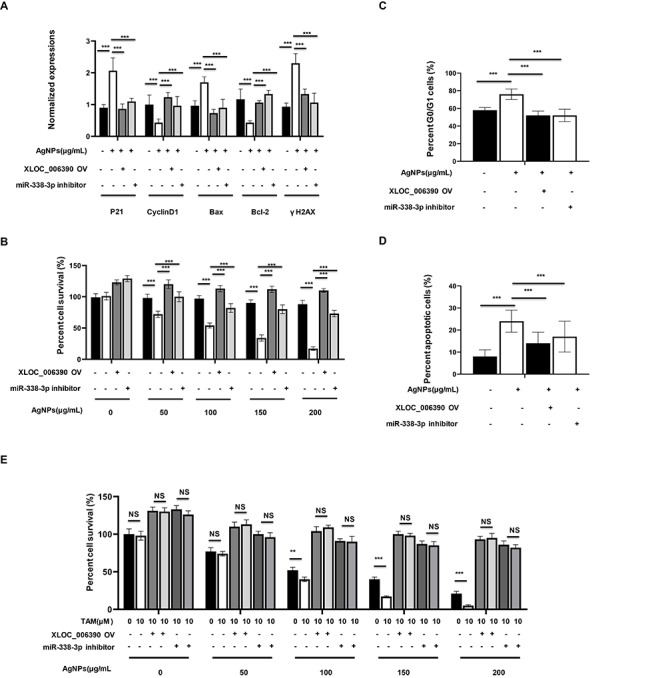

XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis-mediated cytotoxicity of AgNPs and the function of sensitizing tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells to tamoxifen

Then, we asked whether XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis-mediated cytotoxicity of AgNPs against breast cancer cells. First, we found that the mRNA levels of p21, cyclin D1, Bax, Bcl-2 and γH2AX, which were regulated by AgNPs, could be reversed by XLOC_006390 OV or miR-338-3p inhibitor treatment (Fig. 5A). Meanwhile, the cytotoxicity of AgNPs against MCF7 decreased when the cells were pretransfected with XLOC_006390 OV or miR-338-3p inhibitor (Fig. 5B). Also, the regulatory effect of AgNPs on cell cycle and apoptosis could be reversed by XLOC_006390 OV or miR-338-3p inhibitor treatment (Fig. 5C and D). Moreover, AgNPs can weaken the drug resistance of MCF7-Re cells to tamoxifen, and this function will be reversed under XLOC_006390 OV or miR-338-3p inhibitor pretreatment. Collectively, above results demonstrated that XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis-mediated cytotoxicity of AgNPs and the function of sensitizing tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells to tamoxifen.

Figure 5.

XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis-mediated cytotoxicity of AgNPs and its function of sensitizing tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells to tamoxifen. (A) MCF7 cells were transfected with or without XLOC_006390 OV plasmid, or with or without miR-338-3p inhibitor, together with 150 μg/ml AgNPs treatment for 24 h, and then the mRNA expressions of the targets involved in the cell cycles (P21 and cyclin D1), apoptosis progressions (Bax and BCL-2) and DNA damages (γH2AX) were determined by qRT-PCR assay. (B) The MCF7 cells were transfected with or without XLOC_006390 OV plasmid, or with or without miR-338-3p inhibitor, and then were treated with AgNPs at concentration ranges from 50 to 200 μg/ml for 24 h, and then the percent cell survival (%) were determined in comparing with the control cells without AgNPs treatment. (C and D) The (C) cell cycles and (D) apoptosis rate in cells described in (A) were determined. (E) MCF7-Re cells (tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells) were transfected with or without XLOC_006390 OV plasmid, or with or without miR-338-3p inhibitor, and then treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM) at 10 μM or not, together with AgNPs at concentration ranges from 50 to 200 μg/ml or not for 24 h, and then the percent cell survival (%) were determined.

Discussions

Agents with specific cytotoxicities on cancer cells are generally considered to have anticancer potential. AgNPs-based approaches provided a potential way to fight drug resistance and reduce the toxicity related to chemotherapy drugs [18]. In this study, we synthesized AgNPs and found that it has strong cytotoxicities on breast cancer cells. Especially, to our best knowledge, this work is very early exploration on the cytotoxicities of AgNPs against patient-derived breast cancer in vitro. Usually, there are individual differences among patients with the same type of tumor, including the molecular expression differences in tumor cells and their drug-resistant patterns. Meanwhile, due to the existence of cross resistance among different therapy methods, the treatment options for clinically drug-resistant tumor cases are extremely limited. For example, tamoxifen-induced radioresistance might pose a problem for patients who receive neoadjuvant tamoxifen treatment and subsequently receive radiotherapy after surgery [19]. One of the highlights of this study is that AgNPs have strong cytotoxicities on all the breast cancer cell lines and clinically isolated breast cancer cells, with the IC50s at about 150 μg/ml for all, regardless of whether they were tamoxifen resistant or not, and whether they were metastatic or in situ. These results indicated that AgNPs treatment is a very ideal potential antibreast cancer method, which can deal with the clinical refractory drug-resistant breast cancer cases.

Several previous works have also reported that AgNPs exhibit strong inhibitory effect in cancers through regulating several tumor-related signaling pathways. Gurunathan et al. demonstrated that the AgNPs regulated the oxidation level and cell cycle phenotype through GADD45G in the p53 pathway [20]. Li et al. reported that AgNPs could induce protective autophagy via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta/Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling [21]. Many research groups have realized that AgNPs would regulate a large number of complex signaling pathways to achieve their antitumor functions. In this study, we found that AgNPs treatment could induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and promote apoptosis/necrosis rate significantly in breast cancer cells, and these results were correlated with the regulation of cell cycle markers [P21 (positive correlated) and cyclin D1 (negative correlated)] and apoptosis markers [BAX (positive correlated) and BCL-2 (negative correlated)]. From the flow cytometry data, we found that although the increase of late apoptosis was the main way for AgNPs to regulate apoptosis, the ratio of early apoptotic cells, together with early apoptosis markers (γH2AX), was also significantly upregulated by AgNPs treatment. These results suggested that AgNPs might play the cytotoxicity role by regulating multiple cell functions, including cell cycle, and various type of cell deaths.

In order to identify the AgNPs-related pathways, transcriptome technology has been applied to genome-wide analysis in response to AgNPs treatment [21]. LncRNAs have been reported to show different expression patterns in cancer cells compared with normal cases, and additional lncRNAs elements were detected in multiple types of cancers, suggesting important roles in cancer development, progress and anomaly [11]. Thus, an understanding of the AgNPs-related lncRNAs profile may help to determine the contribution of this particular type to the complex functions of the AgNPs. However, this field has just started, and only sporadic reports have identified some lncRNAs related to AgNPs [22]. In this study, our microarray analysis combined with following qRT-PCR validations showed that AgNPs decreased the lncRNAs XLOC_006390 expressions, coupled to inhibited cell proliferation, altered cell cycle and apoptotic phenotype. The changes of XLOC_006390 expressions induced by AgNPs have been observed in all the tested breast cancer cell lines and primary breast cancer cells, indicating that this function of AgNPs has universal significance. Meanwhile, this modulation made us ask whether XLOC_006390 mediate the AgNPs functions.

Recently, it has been found that the interaction between lncRNAs and miRNAs affects post-transcriptional regulation by inhibiting miRNA activity [17]. In the current study, we found that miR-338-3p could be directly targeted by XLOC_006390, and AgNPs treatment significantly upregulated the miR-338-3p expressions through XLOC_006390 inhibition. Furthermore, XLOC_006390 OV or miR-338-3p inhibitor treatment can reverse AgNPs’ cytotoxicity role, indicating that XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p axis may mediate the regulatory role of AgNPs against breast cancer cells.

Most lncRNA/miRNA axis function through regulating the miRNA target genes [23], and there have been many reports describing the antitumor role of miR-338-3p and its targets [24–26]. Jia et al. [24] demonstrated that miR-338-3p inhibited osteosarcoma cells growth and metastasis by targeting RUNX2/CDK4. Lu et al. [25] indicated that miR-338-3p regulates the proliferation, apoptosis and migration of colon cancer cells by targeting MACC1. Tong et al. [26] reported that miR-338-3p targeted SOX4 to play the antitumor role against renal cell carcinoma. These results suggested that miR-338-3p may play antitumor role by targeting different oncogenes in different cancer cells. This work demonstrated that miR-338-3p could target SOX4 in breast cancer cells, and AgNPs can inhibit the SOX4 expression by regulating XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p axis. Moreover, overexpression of SOX4 can reverse the function of AgNPs, which indicated that XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis might be the key component to mediate the AgNPs’ functions.

It has been indicated that AgNPs also have cytotoxic effects on normal cells, tested both in vitro and in vivo [27], and this hinders its application as an antitumor drug alone. Therefore, some studies have pointed out that AgNPs may become an assistant agent, which can be used together with other anticancer drugs [28–30]. Interestingly, we found that AgNPs can sensitize tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells to tamoxifen, and this function was also proved to be XLOC_006390/miR-338-3p/SOX4 axis mediated in this study. However, although SOX4 has been reported to be associated with the resistance to many anticancer drugs, such as cisplatin [31], the relationship between SOX4 and tamoxifen resistance has not been clarified, which needs to be further studied. Nevertheless, this study is still meaningful because these results suggest that the combination of AgNPs and tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer may solve the problem of tamoxifen resistance, and therefore reduce the amount of AgNPs and tamoxifen. Taken together, our results provide a new clue for the antitumor mechanism of AgNPs, and a new way for drug development by using AgNPs.

Conflict of Interest

We declare that all the authors have no conflict of interest.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Harbin Medical University and all the experiments were carried out according to principles of Helsinki Declaration.

References

- 1. Akram M, Iqbal M, Daniyal M et al. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol Res 2017;50:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahn EH, Yang H, Hsieh CY et al. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic and cancer-protective properties of sphingosine and C2-ceramide in a human breast stem cell derived carcinogenesis model. Int J Oncol 2019;54:655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colović M, Todorović M, Colović N et al. Appearance of estrogen positive bilateral breast carcinoma with HER2 gene amplification in a patient with aplastic anemia. Pol J Pathol 2014;65:66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011;378:771–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu Y, Liu Y, Zhang C et al. Tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells are resistant to DNA-damaging chemotherapy because of upregulated BARD1 and BRCA1. Nat Commun 2018;9:1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verkhovskii R, Kozlova A, Atkin V et al. Physical properties and cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles under different polymeric stabilizers. Heliyon 2019;5:e01305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gurunathan S, Park JH, Han JW et al. Comparative assessment of the apoptotic potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Bacillus tequilensis and Calocybe indica in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells: targeting p53 for anticancer therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2015;10:4203–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kovács D, Igaz N, Keskeny C et al. Silver nanoparticles defeat p53-positive and p53-negative osteosarcoma cells by triggering mitochondrial stress and apoptosis. Sci Rep 2016;6:27902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen W, Yang X, Zhao Y et al. lncRNA-cox2 enhance the intracellular killing ability against mycobacterial tuberculosis via up-regulating macrophage M1 polarization/nitric oxide production. Int J Clin Exp Med 2019;12:2402–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu GC, Pan HF, Leng RX et al. Emerging role of long noncoding RNAs in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhan A, Soleimani M, Mandal SS. Long noncoding RNA and cancer: a new paradigm. Cancer Res 2017;77:3965–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mahmood M, Li Z, Casciano D et al. Nanostructural materials increase mineralization in bone cells and affect gene expression through miRNA regulation. J Cell Mol Med 2011;15:2297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salvioni L, Galbiati E, Collico V et al. Negatively charged silver nanoparticles with potent antibacterial activity and reduced toxicity for pharmaceutical preparations. Int J Nanomedicine 2017;12:2517–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Faridi N, Bathaie SZ, Abroun S et al. Isolation and characterization of the primary epithelial breast cancer cells and the adjacent normal epithelial cells from Iranian women’s breast cancer tumors. Cytotechnology 2018;70:625–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jurisic V, Srdic-Rajic T, Konjevic G et al. TNF-α induced apoptosis is accompanied with rapid CD30 and slower CD45 shedding from K-562 cells. J Membr Biol 2011;239:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luan X, Wang Y. LncRNA XLOC_006390 facilitates cervical cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis as a ceRNA against miR-331-3p and miR-338-3p. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paraskevopoulou MD, Vlachos IS, Karagkouni D et al. DIANA-LncBase v2: indexing microRNA targets on non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Y, Chang Y, Lian X et al. Silver nanoparticles for enhanced Cancer Theranostics: in vitro and in vivo perspectives. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2018;14:1515–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Post AEM, Smid M, Nagelkerke A et al. Interferon-stimulated genes are involved in cross-resistance to radiotherapy in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:3397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Park C et al. Cytotoxic potential and molecular pathway analysis of silver nanoparticles in human colon cancer cells HCT116. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li L, Li L, Zhou X et al. Silver nanoparticles induce protective autophagy via Ca2+/CaMKKβ/AMPK/mTOR pathway in SH-SY5Y cells and rat brains. Nanotoxicology 2019;13:369–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodríguez-Razón CM, Yañez-Sánchez I, Ramos-Santillan VO et al. Adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis in different molecular portraits of breast cancer treated with silver nanoparticles and its pathway-network analysis. Int J Nanomedicine 2018;13:1081–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomson DW, Dinger ME. Endogenous microRNA sponges: evidence and controversy. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:272–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jia F, Zhang Z, Zhang X. MicroRNA-338-3p inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in osteosarcoma cells by targeting RUNX2/CDK4 and inhibition of MAPK pathway. J Cell Biochem 2019;120:6420–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu M, Huang H, Yang J et al. miR-338-3p regulates the proliferation, apoptosis and migration of SW480 cells by targeting MACC1. Exp Ther Med 2019;17:2807–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tong Z, Meng X, Wang J et al. MicroRNA-338-3p targets SOX4 and inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of renal cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med 2017;14:5200–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao M, Zhao B, Chen M et al. Nrf-2-driven long noncoding RNA ODRUL contributes to modulating silver nanoparticle-induced effects on erythroid cells. Biomaterials 2017;130:14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moradi-Sardareh H, Basir HRG, Hassan ZM et al. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles on different tissues of Balb/C mice. Life Sci 2018;211:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Behnam MA, Emami F, Sobhani Z et al. Novel combination of silver nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes for plasmonic photo thermal therapy in melanoma cancer model. Adv Pharm Bull 2018;8:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fahrenholtz CD, Swanner J, Ramirez-Perez M et al. Heterogeneous responses of ovarian cancer cells to silver nanoparticles as a single agent and in combination with cisplatin. J Nanomater 2017;2017:5107485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun R, Jiang B, Qi H et al. SOX4 contributes to the progression of cervical cancer and the resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug through ABCG2. Cell Death Dis 2015;6:e1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang XF, Liu ZG, Shen W et al. Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, applications, and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khorrami S, Zarrabi A, Khaleghi M et al. Selective cytotoxicity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against the MCF-7 tumor cell line and their enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Int J Nanomedicine 2018;13:8013–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swanner J, Synthesis SR. Purification, characterization, and imaging of Cy3-functionalized fluorescent silver nanoparticles in 2D and 3D tumor models. Methods Mol Biol 2018;1790:209–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]