Abstract

Our previous study has demonstrated that two low molecular weight-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (LMW-PAHs), phenanthrene (Phe) and fluorene (Flu), alone and as a mixture could induce oxidative damage and inflammation in A549 cells. However, the associated mechanisms have not been well discussed. The aim of this study was to further investigate the roles of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways in the inflammatory effects in A549 cells induced by Phe, Flu and their mixture. The results indicated that Phe, Flu and their mixture significantly activated PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways by increasing the phosphorylation levels of PI3K, AKT, IκBα and NF-κB p65. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokine expressions of TNF-α and IL-6 induced by the binary mixture of Phe and Flu were all alleviated by co-treatment with PI3K/AKT and NF-κB specific inhibitors (LY294002 and BAY11-7082). The results suggested that PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways played an important role in LMW-PAHs induced inflammation in A549 cells.

Keywords: low molecular weight-PAHs, inflammation, PI3K/AKT, NF-κB

Introduction

The incomplete combustion of organic fuels causes the emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the air, which are large family of environmental pollutants [1]. Among all PAHs, low molecular weight-PAHs (LMW-PAHs, up to four benzene rings) widely exist in gas and particulate matters [2]. These PAHs are generally considered as weak ligands of aromatic hydrocarbon receptors (AhR) and their toxicity is lower compared to PAHs with five or more benzene rings [2]. Nevertheless, several LMW-PAHs were shown to elicit effects on disruption of cell proliferation control and tumor promotion in rat liver epithelial cells [3]. And some specific urinary LMW-PAHs metabolites were potentially associated with reduced lung function in the general Chinese population [4], which suggested the harmful influence of LMW-PAHs exposure on human health.

Our previous field study revealed that rural women exposed to PAHs were significantly associated with oxidative damage and immune impairments in northwest China [5], and through the composition analysis of PAHs it has been discovered that phenanthrene (Phe) and fluorene (Flu), two LMW-PAHs, were ranked higher among 16 priority PAHs in the local atmosphere (unpublished data). And the later animal study showed that Phe could lead to oxidative stress and inflammation in female rats [6]. Furthermore, our in vitro experiments found that Phe and Flu alone and as a mixture could also induce oxidative damage and inflammatory effects in A549 cells [7]. However, the mechanisms involved in this process have not been clarified yet.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway is involved in fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, survival and immune regulation [8]. Many factors, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and others extracellular stimuli, could activate PI3K to generate phosphoinositide-3, 4, 5-triphosphate (PIP3), which recruits AKT to cell membranes and to be phosphorylated [9]. Activated AKT targets various downstream molecules and therefore regulates many biological processes. Moreover, nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) is one of the downstream effectors of AKT and performs a critical regulatory role in inflammation [10]. Normally, NF-κB binds to specific inhibitory protein I kappa B (IκB) and is presented in the cytoplasm in an inactive form [11]. Upon activation, IκB is promptly phosphorylated and degraded, which permits the freeing NF-κB to be activated and translocated into nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of downstream genes and promotes the release of inflammation-associated factors, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF-α [12]. It has been reported that LPS could induce oxidative stress-related inflammation in C57BL/6 mice via the activation of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways [13]. However, it is not certain whether the oxidative stress and inflammatory responses induced by LMW-PAHs could be regulated through PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Our previous study has indicated the inflammatory effects of two LMW-PAHs (Phe and Flu) alone and as a mixture on A549 cells [7]. In the present study, the roles of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways were further investigated to explore the underlying toxic mechanisms induced by LMW-PAHs in A549 cells.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents

Phe (CAS: 85-01-8, 98% purity) and Flu (CAS: 86-73-7, 98% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose, phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA were purchased from Biological Industries, Israel. LY294002 (PI3K/AKT inhibitor) and BAY11-7082 (NF-κB inhibitor) were gained from ApexBio Technology, USA. Antibodies against TNF-α and IL-6 were provided by Abcam Biotechnology, Cambridge. Antibodies against PI3K, AKT, p-AKT, IκBα, p-IκBα, NF-κB p65 and p-NF-κB p65 were provided by cell signaling technology, USA. Antibody against p-PI3K was acquired from Signal Antibody, USA.

Cell culture and treatments

Human lung epithelial A549 cells were obtained from Cancer Hospital of Gansu Province, China. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Phe, Flu and Phe + Flu (the mix) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and then diluted in culture medium containing 10% FBS to the concentrations of 200, 400 and 600 μM [14, 15]. The final concentration of DMSO in experiments was 0.8% [16, 17].

Western blot

After treatment for 24 h, A549 cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA) containing 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1% phosphatase inhibitor for 30 min on ice. Then, cell lysates were centrifuged at 12 000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the proteins in the supernatants were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). About 30 μg proteins were separated in 8–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) and transferred on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature in 5% nonfat milk and then were incubated with primary antibodies including PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT, p-AKT, IκBα, p-IκBα, NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, TNF-α and IL-6 at 4°C overnight. After that, membranes were washed in TBST buffer 10 min for three times and incubated with secondary antibody for 2 h. Finally, the target proteins were visualized in a Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, USA) by ECL detection kit (Beyotime, China). The images were analyzed by Image Pro-Plus 6.0 software.

Inhibitor experiments

To inspect the signaling pathways involved in the effects of LMW-PAHs exposure-induced inflammation, cells were pre-incubated with the PI3K/AKT inhibitor (LY294002, 20 μM) [18] or NF-κB inhibitor (BAY11-7082, 20 μM) [19] for 1 h before treatment with the binary mixture of Phe and Flu (400 μM). Then, western blot analyses were carried out to detect the effects of inhibitors on protein expressions of AKT, p-AKT, NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, TNF-α and IL-6.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS 24.0 software and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with least-significant difference test. If the variances were nonhomogeneous, the data were analyzed using nonparametric test (Kruskal–Wallis H test). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of Phe, Flu and the mix on PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in A549 cells

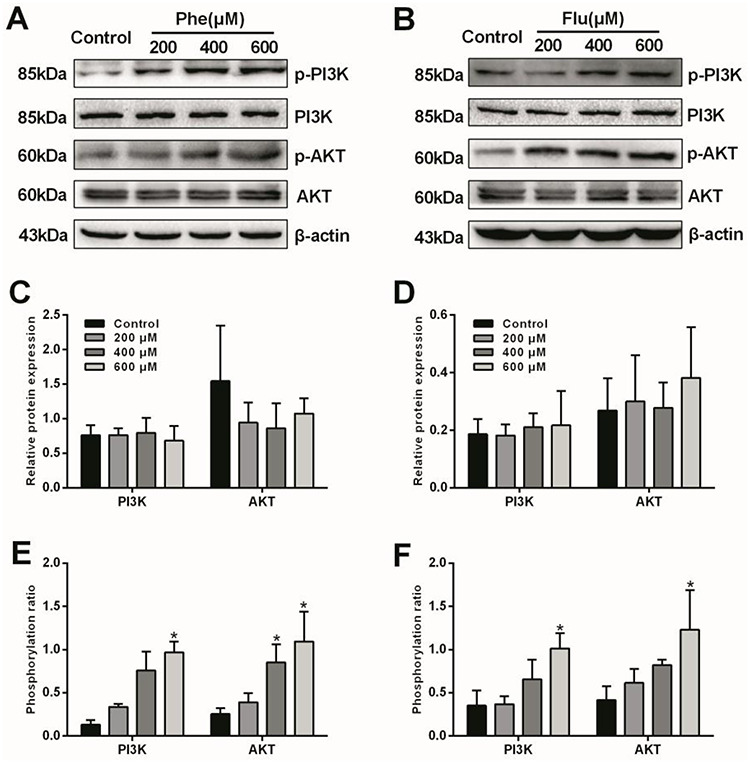

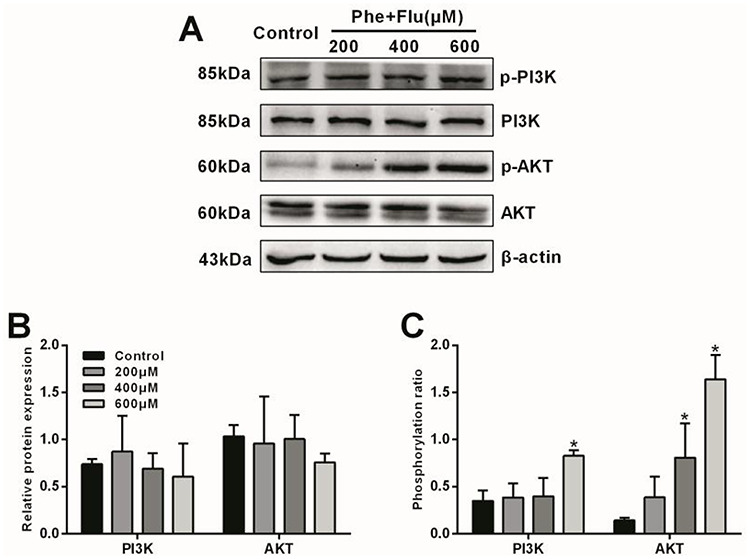

To investigate the toxic effects of Phe, Flu and the mix on PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, the protein expressions of PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT and p-AKT in A549 cells were detected by western blot (Figs 1 and 2). Compared with the control group, the total protein expressions of PI3K and AKT were no significant difference in all concentrations of Phe, Flu and the mix groups (P > 0.05), while the phosphorylation ratio of PI3K was significantly increased in 600 μM group and the phosphorylation ratio of AKT was increased in 400 and 600 μM groups by treating with Phe and the mix (P < 0.05), separately. Meanwhile, the phosphorylation ratios of PI3K and AKT were elevated at 600 μM by treating with Flu (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of Phe and Flu on PI3K/AKT pathway in A549 cells: Total and phosphorylated protein levels by Western blot (A, B); Semi-quantitative analysis of PI3K and AKT protein expressions (C, D); Phosphorylation ratios of PI3K and AKT (E, F). Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group.

Figure 2.

Effects of the Mix on PI3K/AKT pathway in A549 cells: Total and phosphorylated protein levels by Western blot (A); Semi-quantitative analysis of PI3K and AKT protein expressions (B); Phosphorylation ratios of PI3K and AKT (C). Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group.

Effects of Phe, Flu and the mix on NF-κB signaling pathway in A549 cells

The protein expressions of IκBα, p-IκBα, NF-κB p65 and p-NF-κB p65 were determined to explore the toxic effects of Phe, Flu and the mix on NF-κB signaling pathway (Figs 3 and 4). Compared with the control group, the total protein expressions of IκBα and NF-κB p65 were no significant change in all concentrations of Phe, Flu and the mix groups (P > 0.05), while the phosphorylation ratio of IκBα was increased in 600 μM group and the phosphorylation ratio of NF-κB p65 was increased in 400 and 600 μM groups by treating with Phe (P < 0.05). And the phosphorylation ratios of IκBα and NF-κB p65 were both increased in 600 μM groups by treating with Flu (P < 0.05). Moreover, the phosphorylation ratios of IκBα and NF-κB p65 were raised at 400 and 600 μM by treating with the mix (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of Phe and Flu on NF-κB pathway in A549 cells: Total and phosphorylated protein levels by Western blot (A, B); Semi-quantitative analysis of IκBα and NF-κB p65 protein expressions (C, D); Phosphorylation ratios of IκBα and NF-κB p65 (E, F). Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group.

Figure 4.

Effects of the Mix on NF-κB pathway in A549 cells: Total and phosphorylated protein levels by Western blot (A); Semi-quantitative analysis of IκBα and NF-κB p65 protein expressions (B); Phosphorylation ratios of IκBα and NF-κB p65 (C). Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group.

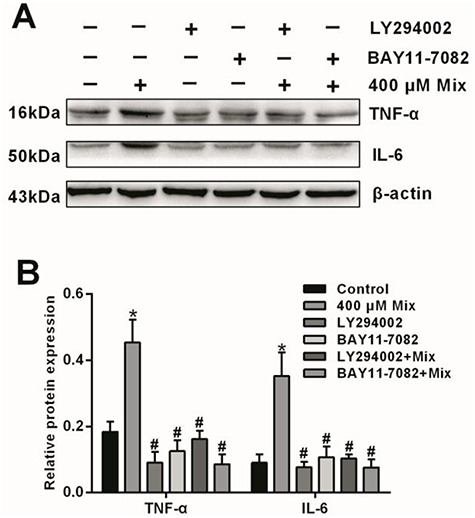

Roles of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB in LMW-PAHs exposure-induced inflammation in A549 cells

In order to confirm the roles of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways involved in LMW-PAHs exposure-induced inflammation in A549 cells, we further conducted experiments with the inhibitors of PI3K/AKT (LY294002) and NF-κB (BAY11-7082). As shown in Fig. 5, the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways were significantly suppressed by their special inhibitors, respectively (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the protein levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured in A549 cells (Fig. 6). Compared with the control group, the protein expressions of TNF-α and IL-6 were increased after treating with 400 μM mix of Phe and Flu (P < 0.05), while pretreatment with LY294002 and BAY11-7082 significantly reduced TNF-α and IL-6 protein levels, compared with the mix group (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of the Mix on PI3K/AKT and NF-κB activation after pre-treated with specific inhibitors in A549 cells: Total and phosphorylated protein levels by Western blot (A, C); Semi-quantitative analysis of AKT and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation ratios (B, D). Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group; #p<0.05 compared with the Mix group.

Figure 6.

Effects of the Mix on of inflammatory cytokines expression after pretreated with PI3K/AKT and NF-κB specific inhibitors in A549 cells: Protein levels (A) and semi-quantitative analysis (B) of TNF-α and IL-6. Data were presented as mean ± SD (n=3). *p<0.05 compared with the control group; #p<0.05 compared with the Mix group.

Discussion

LMW-PAHs, the main components of PAHs, are distributed in ambient air with abundant concentrations [20]. There is increasing evidence to suggest the adverse effects of LMW-PAHs exposure [21]. A recent study showed that LMW-PAHs could modulate the inflammatory cytokines release and impair macrophage function at environmentally relevant concentrations [22]. Exposure to four LMW-PAHs (naphthalene, anthracene, pyrene and Phe) alone or as a mixture could induce cell-specific toxic effects in placental cell lines [23]. Our previous study also found that Phe and Flu, two typical LMW-PAHs with high concentrations in our preliminary field survey, were capable of inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and pro-inflammatory factors expression in A549 cells [7], while the mechanisms involved in these processes remain limited. In this study, we provided evidence to demonstrate that the potential mechanisms of pulmonary inflammation induced by LMW-PAHs in A549 cells were at least partly related to PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways.

It is well reported that PI3K/AKT pathway was involved in the oxidative stress and inflammation response. Studies have shown that oxidative damage and inflammatory responses induced by nitro-PAHs and amino-PAHs in A549 cells were linked to the activation of PI3K/AKT pathway [24, 25]. Particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) has been found to induce ROS generation and oxidative stress via activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [18]. Our present research also revealed that Phe, Flu and their mixture could activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, as evidenced by the increased phosphorylation levels of PI3K and AKT. In addition, NF-κB pathway has been considered to play a predominant role in inflammatory conditions [26]. Song et al. [27] reported that PM2.5-induced ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines production was correlated with NF-κB activation in human airway epithelial cells. Another study showed that PAHs could promote inflammatory process through the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway in A549 cells [28]. In consistence with the above findings, our current results found that Phe, Flu and their mixture upregulated the phosphorylated levels of IκBα and NF-κB p65 in A549 cells, which indicates that the NF-κB signaling pathway was activated.

Considering the resemble effects of Phe, Flu and their mixture on PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways, the binary mixture of Phe and Flu were chosen to perform the next inhibitor experiments and further identify the roles of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways in regulating inflammatory responses induced by LMW-PAHs. Although studies have shown that AKT could phosphorylate NF-κB subunits and affect its translocation and activation [10], there were many other signal molecules that participated in the activation of NF-κB (such as ROS or TNF-α) [26, 29]. Therefore, PI3K/AKT and NF-κB specific inhibitors (LY294002 and BAY11-7082) were used separately to block the activity of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. It has been reported that LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines expression could be alleviated by treating with LY294002 and BAY11-7082 in U937 macrophages [30]. Similarly, our results found that the protein levels of TNF-α and IL-6 induced by the binary mixture of Phe and Flu were both attenuated by co-treatment with LY294002 or BAY11-7082 in A549 cells, suggesting that both PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathway were necessary for LMW-PAHs induced inflammation. In addition, other pathways, such as MAPK kinase, has also been reported to play an important role in regulating pro-inflammatory mediator expression and inflammatory reaction [31], while their effects on LMW-PAHs exposure-induced inflammation have yet to be explicated and warrant further investigation in the future studies.

Plenty of studies have shown that excessive production of ROS was a key step to lead to inflammation [29, 32]. Our previous study also found that inflammatory effects induced by Phe, Flu and their mixture were closely associated with ROS generation and oxidative stress [7]. And in this study, we further found that PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways played an important role in LMW-PAHs induced inflammation, which complemented and improved the previous results. Furthermore, it should be illustrated that the trial dose in this study was selected by our previous cell viability assays. Considering the relatively high doses in this study and only two LMW-PAHs involved, we will aim at more LMW-PAHs in the future studies and further investigate through in vivo and in vitro experiments how long-term exposure to environmental-related concentrations of LMW-PAHs affects human health.

Conclusion

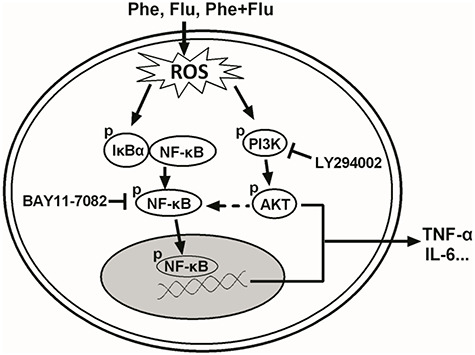

In conclusion, the results in this study extended previous observations and suggested the underlying toxic mechanisms induced by Phe, Flu and their mixture in A549 cells. It is possible that ROS generation and oxidative injury are the initial events in LMW-PAHs exposure-induced cytotoxicity, and PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways are involved in the subsequent process of inflammation in A549 cells. Therefore, our study has revealed a possible cytotoxic mechanism of LMW-PAHs exposure (Fig. 7), and further mechanisms involved in these processes remain to be determined in the future.

Figure 7.

A schematic diagram that illustrates the signaling pathways involved in LMW-PAHs exposure-induced inflammation in A549 cells. Phe, Flu and their mixture acts via up-regulation of intracellular ROS level and further induction the phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT and IκBα/NF-κB, which results in PI3K/AKT and NF-κB activation and finally induces the expression of pro-inflammation cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81828011).

Reference

- 1. Shen H, Huang Y, Wang R et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions. Environ Sci Technol 2013;47:6415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boström C, Gerde P, Hanberg A et al. Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:451–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kabátková M, Svobodová J, Pěnčíková K et al. Interactive effects of inflammatory cytokine and abundant low-molecular-weight PAHs on inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication, disruption of cell proliferation control, and the AhR-dependent transcription. Toxicol Lett 2015;232:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou Y, Sun H, Xie J et al. Urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites and altered lung function in Wuhan, China. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:835–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yao Y, Wang D, Ma H et al. The impact on T-regulatory cell related immune responses in rural women exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in household air pollution in Gansu, China: a pilot investigation. Environ Res 2019;173:306–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ma H, Wang H, Zhang H et al. Effects of phenanthrene on oxidative stress and inflammation in lung and liver of female rats. Environ Toxicol 2020;35:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo H, Zhang Z, Wang H et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory effects in human lung epithelial A549 cells induced by phenanthrene, fluorene and their binary mixture. Environ Toxicol 2021;36:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pompura S, Dominguez-Villar M. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in regulatory T-cell development, stability, and function. J Leukoc Biol 2018;103:1065–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qiao Q, Jiang Y, Li G. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT-NF-κB pathway with curcumin enhanced radiation-induced apoptosis in human Burkitt's lymphoma. J Pharmacol Sci 2013;121:247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qi S, Xin Y, Guo Y et al. Ampelopsin reduces endotoxic inflammation via repressing ROS-mediated activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;12:278–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu M, Zhang Q, Chen K et al. The regulatory effect of oxymatrine on the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced MS1 cells. Phytomedicine 2017;36:153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoesel B, Schmid J. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer 2013;12:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhong W, Qian K, Xiong J et al. Curcumin alleviates lipopolysaccharide induced sepsis and liver failure by suppression of oxidative stress-related inflammation via PI3K/AKT and NF-κB related signaling. Biomed Pharmacother 2016;83:302–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuan Q, Chen Y, Li X et al. Ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) induces oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory response via up-regulating the expression of CYP1A1/1B1 in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2019;839:40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou J, Huang Z, Ni X et al. Piperlongumine induces apoptosis and G(2)/M phase arrest in human osteosarcoma cells by regulating ROS/PI3K/Akt pathway. Toxicol In Vitro 2020;65:104775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cardeno A, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Aparicio-Soto M et al. Unsaponifiable fraction from extra virgin olive oil inhibits the inflammatory response in LPS-activated murine macrophages. Food Chem 2014;147:117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu A, Sun Y, Zhong Q et al. Effect of euphorbia factor L1 on oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy in human gastric epithelial cells. Phytomedicine 2019;64:152929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deng X, Rui W, Zhang F et al. PM2.5 induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PIK3/AKT signaling pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Cell Biol Toxicol 2013;29:143–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang R, Wang W, Li A et al. Lipopolysaccharide enhances DNA-induced IFN-β expression and autophagy by upregulating cGAS expression in A549 cells. Exp Ther Med 2019;18:4157–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen L, Hu G, Fan R et al. Association of PAHs and BTEX exposure with lung function and respiratory symptoms among a nonoccupational population near the coal chemical industry in northern China. Environ Int 2018;120:480–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Osgood R, Upham B, Bushel P et al. Secondhand smoke-prevalent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon binary mixture-induced specific Mitogenic and pro-inflammatory cell Signaling events in lung epithelial cells. Toxicol Sci 2017;157:156–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang C, Yang J, Zhu L et al. Never deem lightly the “less harmful” low-molecular-weight PAH, NPAH, and OPAH - disturbance of the immune response at real environmental levels. Chemosphere 2017;168:568–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drwal E, Rak A, Grochowalski A et al. Cell-specific and dose-dependent effects of PAHs on proliferation, cell cycle, and apoptosis protein expression and hormone secretion by placental cell lines. Toxicol Lett 2017;280:10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu M, Jiang Y, Liu M et al. Amino-PAHs activated Nrf2/ARE anti-oxidative defense system and promoted inflammatory responses: the regulation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2018;7:465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shang Y, Zhou Q, Wang T et al. Airborne nitro-PAHs induce Nrf2/ARE defense system against oxidative stress and promote inflammatory process by activating PI3K/Akt pathway in A549 cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2017;44:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lawrence T The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009;1:a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song L, Li D, Li X et al. Exposure to PM2.5 induces aberrant activation of NF-κB in human airway epithelial cells by downregulating miR-331 expression. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2017;50:192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pei X, Nakanishi Y, Inoue H et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons induce IL-8 expression through nuclear factor kappaB activation in A549 cell line. Cytokine 2002;19:236–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu C, Lee T, Chen Y et al. PM2.5-induced oxidative stress increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in lung epithelial cells through the IL-6/AKT/STAT3/NF-κB-dependent pathway. Part Fibre Toxicol 2018;15:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haque M, Jantan I, Harikrishnan H et al. Standardized extract of Zingiber zerumbet suppresses LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses through NF-κB, MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in U937 macrophages. Phytomedicine 2019;54:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma Y, Zhang J, Liu Y et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester alleviates asthma by regulating the airway microenvironment via the ROS-responsive MAPK/Akt pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 2016;101:163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tseng C, Wang J, Chao M. Causation by diesel exhaust particles of endothelial dysfunctions in cytotoxicity, pro-inflammation, permeability, and apoptosis induced by ROS generation. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2017;17:384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]