Abstract

Background

Early screening and intervention therapies are crucial to improve the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with bone metastasis. We aimed to identify serum lncRNA as a prediction biomarker in HCC bone metastasis.

Methods

The expression levels of lnc34a in serum samples from 157 HCC patients were detected by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis were performed to determine statistically significant variables.

Results

Expression levels of lnc34a in serum from HCC patients with bone metastasis were significantly higher than those without bone metastasis. The high expressions of lnc34a, vascular invasion and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage were associated with bone metastasis by analysis. Moreover, lnc34a expression was specifically associated with bone metastasis rather than lung or lymph node metastasis in HCC.

Conclusions

High serum lnc34a expression was a independent risk factor for developing bone metastasis in HCC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-07808-6.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Bone metastasis, Serum, lnc34a

Background

The morbidity and mortality of liver cancer continues to rise among both men and women [1]. Hepatocellular cancer (HCC), as the predominant pathological type of primary liver cancer, is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [2]. With the advancement of diagnostic technologies and therapeutic procedures for HCC, the overall survival has been improved in HCC patients recently [3]. However, recurrence and metastasis remain the major obstacle to reduce the mortality of HCC patients [3, 4]. The bone is the third most frequent site of distant metastasis derived from HCC, after the lungs and lymph nodes [5]. Bone colonization severely affects the life quality for HCC patients, with a median survival of 7.4 months [6]. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify potential and novel biomarkers for the early screening, diagnosing and prognosis of HCC patients with bone metastasis.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a highly heterogeneous group of transcripts longer than 200 nt with limited or no protein coding capacity [7]. Many studies have shown that aberrantly expressed lncRNAs may serve as the potential biomarkers for early diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis in various cancers [8]. LncRNAs in tissue have great potential as biomarkers in cancer, while its clinical application was limited for the invasive procedure which is not easily available and may lead to complications [9].

Circulating RNA in blood is an emerging field concerned with its noninvasive diagnosis identity [10]. Up to date, more and more lncRNAs in serum or plasma have been identified as novel biomarkers for diagnosis, target therapy, and prognosis in cancers. For instance, Iempridee, T et al. (2018). identified lncRNAs AC017078.1 and XLOC_011152 as potential serum biomarkers with good diagnostic potential for cervical cancer [11]. Long noncoding RNA PCAT1, present in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma(ESCC) cell-derived exosomes, was higher in the serum of ESCC patients and may serve as a non-invasive biomarker for ESCC [12]. LINC00899 in serum was used as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia [13]. Besides, increasing lncRNAs were identified as serum biomarkers in HCC [14–17]. For instance, the serum lncRNA uc007biz.1 (LRB1) expression levels may be considered as a novel biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis prediction of HCC, additionally complementing the accuracy of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) [18].

Lnc34a is a novel lncRNA with a full-length of 693 bp transcript and has no protein coding potential. It tends to be elevated in late-stage colorectal cancer. Asymmetric distribution of lnc34a during colon cancer stem cells(CCSC) division leads to the different fate of the daughter cells. Lnc34a regulated self-renewal and cell differentiation mediated by miR-34a [19], which inhibits bone metastasis in various cancers [20, 21]. Our previous study demonstrated that intratumoral Lnc34a were significantly correlated with HCC bone metastasis [22]. However, the application of circulating lnc34a in HCC patients with bone metastasis remains to be elucidated.

In the present study, we investigated the expression levels of lnc34a in serum of HCC patients using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and found that lnc34a level was correlated with HCC bone metastasis. Therefore, these findings suggested that lnc34a in serum may serve as considerable diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for bone metastasis from HCC.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the study according to the committee regulations.

Patients and serum samples

All serum samples were collected from 157 HCC patients with eligibility criteria from December 2008 to October 2014. All of the 157 patients underwent curative hepatectomy in Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. Postoperative pathology verified HCC diagnosis. None of the patients had distant metastases at the time of blood collection. The serum was seperated from venous blood collected within 2 h and sequentially centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, then 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. The serum supernatants were then transferred into RNase−/DNase-free tubes and stored at − 80 °C.

The tumor stage was staged and graded according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system and the Edmondson grading system. Liver function was assessed by the Child-Pugh scoring system. Tumor size was determined by the maximum diameter of the tumor specimen. The extent of vascular invasion was examined under the microscope in the resected specimen.

Follow up

All patients were followed up until December 2016. The follow-up duration ranged from 3 to 96 months (mean 47 months).

All patients were followed up every 3 months after hepatectomy. The follow-up parameters were surveyed as previously described [23], including physical examinations, history documentation, ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen, a chest radiograph, laboratory tests, and so on. Bone scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed immediately for the patients with ostalgia. Bone metastasis was mainly diagnosed by a history of HCC, the clinical symptoms, and the imaging tests. The date from surgery to bone metastasis or death was considered as bone metastasis-free survival [23]. When the bone metastasis detected definitely, the affected bone would undergo radiotherapy. Interventional therapy, such as radiotherapy or surgery was considered for other distant metastasis.

Ribose nucleic acid (RNA) extraction and reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from serum samples using the TRIzol™ LS Reagent (Ambion, Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 0.75 ml of TRIzol LS Reagent was added for each 0.25 ml of serum sample and then 7.2*107 Copies of synthesized exogenous reference λ polyA+ RNA (Takara, China) was added to the homogenized samples for normalization [24]. 0.2 ml of chloroform was added and the homogenized samples was centrifuged. After centrifugation, the aqueous phase was transferred to a clean tube. Then the RNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase by adding 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol and centrifuged. Then 1 ml of 75% ethanol was added into the tubes to wash the RNA pellet after removing the supernatant. Finally, after centrifugation, the RNA pellet was dried and dissolved with 20 μl RNase-free water. The concentration of RNA was detected by using ultraviolet spectrophotometer.

Serum RNA was reversely transcribed into Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, China). Then qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate using SYBR® Green PCR method (Takara, China) with QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The sequences of sense and antisense primers of lnc34a were as follows: 5′-GGAGGCTACACAATTGAACAGG-3′ and 5′-AGTCCGTGCGAAAGTTTGC-3′. The relative expression of lnc34a from serum samples was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized against a synthesized exogenous reference λ polyA+ RNA.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 24.0. Correlations between lnc34a expression and different subgroups stratified by age, gender, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis C virus antibody (HCV-Ab), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT), liver cirrhosis, Child-Pugh score, tumor differentiation, tumor size, tumor number, tumor encapsulation, vascular invasion, BCLC stage, lung metastasis, lymph node metastasis, bone metastasis were analysed by using Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Student’s t test was used for the quantitative analysis. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to determine statistically significant variables. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics

Clinicopathologic characteristics of all HCC patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the study population

| Variable | n of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| ≤ 56 | 78(49.7%) |

| > 56 | 79(50.3%) |

| Gender | |

| male | 142(90.4%) |

| female | 15(9.6%) |

| HBsAg | |

| negative | 28(17.8%) |

| positive | 129(82.2%) |

| HCV-Ab | |

| negative | 152(96.8%) |

| positive | 5(3.2%) |

| AFP | |

| ≤ 20 | 60(38.2%) |

| > 20 | 97(61.8%) |

| ALT | |

| ≤ 40 | 126(80.3%) |

| > 40 | 31(19.7%) |

| γ-GT | |

| ≤ 50 | 96(61.1%) |

| > 50 | 61(38.9%) |

| Liver cirrhosis | |

| no | 34(21.7%) |

| yes | 123(78.3%) |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| A | 151(96.2%) |

| B | 6(3.8%) |

| Tumor differentiation | |

| I–II | 93(59.2%) |

| III–IV | 64(40.8%) |

| Tumor size, cm | |

| ≤ 5 | 107(68.2%) |

| > 5 | 50(31.8%) |

| Tumor number | |

| single | 98(62.4%) |

| multiple | 59(37.6%) |

| Tumor encapsulation | |

| complete | 72(45.9%) |

| none | 85(54.1%) |

| Vascular invasion | |

| no | 112(71.3%) |

| yes | 45(28.7%) |

| BCLC stage | |

| 0-A | 99(63.1%) |

| B-C | 58(36.9%) |

| Lung metastasis | |

| no | 134(85.4%) |

| yes | 23(14.6%) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| no | 137(87.3%) |

| yes | 20(12.7%) |

| Bone metastasis | |

| no | 139(88.5%) |

| yes | 18(11.5%) |

| Lnc34a | |

| low | 77(49.0%) |

| high | 80(51.0%) |

HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV-Ab hepatitis C virus antibody, AFP a-fetoprotein, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GT γ-glutamyl transferase, BCLC-stage Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage

Expression of serum lnc34a levels in patients with HCC

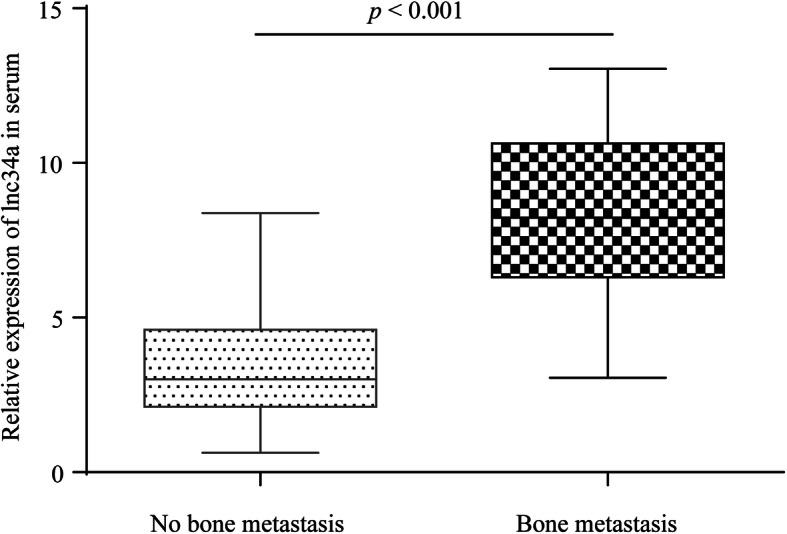

In order to investigate the hypothesis that the serum level of lnc34a is a potential biomarker for the bone metastases of HCC, qRT-PCR for the lnc34a expression detection was performed with serum samples from 18 HCC patients with bone metastases and 139 cases without bone metastases. As shown in Fig. 1, the serum expression levels of lnc34a in patients with bone metastases were significantly higher than that in those without bone involvement. The 157 HCC patients were classified into high serum lnc34a group (n = 80) and low serum lnc34a group (n = 77) according to the median serum lnc34a expression level [25]. Of the 18 patients with bone metastasis, 15 (83.3%) had high lnc34a expression.

Fig. 1.

The serum levels of lnc34a in HCC patients with or without bone metastasis. Expression levels of lnc34a in serum from HCC patients with bone metastasis were significantly higher than those without bone metastasis

Furthermore, the potential prediction value of lnc34a was evaluated by ROC curves. As shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1, the AUC of lnc34a expression was 0.683 (95% CI =0.564–0.802). The sensitivity and specificity of lnc34a to predict bone metastasis in HCC were 83.3 and 53.2%, respectively. Therefore, lnc34a might act as a useful biomarker for discriminating HCC patients with bone metastasis from those without bone metastasis.

Association between serum lnc34a expression levels and clinicopathological factors in patients with HCC

We next analyzed the relationship between the expression of serum lnc34a and clinicopathological characteristics of the 157 HCC patients. As shown in Table 2, the analysis revealed that serum lnc34a levels were significantly related to certain clinicopathological parameters, including vascular invasion (p = 0.032) and BCLC stage (p = 0.014). Almost 82.3% patients in our study were infected with hepatitis B. However, the lnc34a expression was uncorrelated with HBsAg (p = 0.173), which may due to the limited number of patients in this study.

Table 2.

Relationship between serum lnc34a expression and clinicopathological characteristics

| Serum Lnc34a Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Low | High | P |

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 56 | 78 | 40 | 38 | 0.577 |

| > 56 | 79 | 37 | 42 | |

| Gender | ||||

| male | 142 | 69 | 73 | 0.727 |

| female | 15 | 8 | 7 | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| negative | 28 | 17 | 11 | 0.173 |

| positive | 129 | 60 | 69 | |

| HCV-Ab | ||||

| negative | 152 | 76 | 76 | 0.387 |

| positive | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| AFP | ||||

| ≤ 20 | 60 | 31 | 29 | 0.605 |

| > 20 | 97 | 46 | 51 | |

| ALT | ||||

| ≤ 40 | 126 | 61 | 65 | 0.749 |

| > 40 | 31 | 16 | 15 | |

| γ-GT | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 96 | 49 | 47 | 0.530 |

| > 50 | 61 | 28 | 33 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| no | 34 | 18 | 16 | 0.608 |

| yes | 123 | 59 | 64 | |

| Child-Pugh score | ||||

| A | 151 | 73 | 78 | 0.643 |

| B | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||

| I–II | 93 | 43 | 50 | 0.396 |

| III–IV | 64 | 34 | 30 | |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 107 | 49 | 58 | 0.233 |

| > 5 | 50 | 28 | 22 | |

| Tumor number | ||||

| single | 98 | 45 | 53 | 0.313 |

| multiple | 59 | 32 | 27 | |

| Tumor encapsulation | ||||

| complete | 72 | 35 | 37 | 0.920 |

| none | 85 | 42 | 43 | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| no | 112 | 61 | 51 | 0.032 |

| yes | 45 | 16 | 29 | |

| BCLC stage | ||||

| 0-A | 99 | 56 | 43 | 0.014 |

| B-C | 58 | 21 | 37 | |

| Lung metastasis | ||||

| no | 134 | 67 | 67 | 0.566 |

| yes | 23 | 10 | 13 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| no | 137 | 68 | 69 | 0.701 |

| yes | 20 | 9 | 11 | |

| Bone metastasis | ||||

| no | 139 | 74 | 65 | 0.003 |

| yes | 18 | 3 | 15 | |

HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV-Ab hepatitis C virus antibody, AFP a-fetoprotein, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GT γ-glutamyl transferase, BCLC-stage Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage

At the final follow-up, 50 (31.8%) patients were found to have extrahepatic metastases. Among these patients, 23 patients developed lung metastasis, 20 patients developed lymph node metastasis, and 18 patients developed bone metastases. To eliminate the possibility of other extrahepatic metastases affecting the expression of lnc34a, we further carried out a subgroup analysis of its expression with other extrahepatic metastases. Correlation analysis revealed that the serum lnc34a expression level was positive correlated with bone metastasis in HCC (r = 0.233, p = 0.003), while there was no significant correlations between circulating lnc34a expression and lung (r = 0.046, p = 0.566) or lymph node metastasis (r = 0.031, p = 0.701).

Cox regression analysis of potential biomarkers and bone metastasis

As shown in Table 3, univariate analyses indicated that vascular invasion (p < 0.001), and BCLC stage (p = 0.001) and lnc34a expression (p = 0.008) were significantly associated with HCC bone metastasis. However, there was no significant correlation between bone metastasis and clinicopathological factors such as age, gender, HBsAg, HCV-Ab, AFP, ALT, γ-GT, liver cirrhosis, Child-Pugh score, tumor differentiation, tumor size, tumor number and tumor encapsulation. Multivariate analyses further revealed that vascular invasion (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.291–19.157; p < 0.001), BCLC stage (95% CI, 1.244–12.287; p = 0.020), and lnc34a expression (95% CI, 1.107–13.629; p = 0.034) were associated with bone metastasis (Table 4). Therefore, high serum lnc34a expression, vascular invasion and BCLC stage were independent risk factors for bone metastasis prediction in HCC patients.

Table 3.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with bone metastasis in 157 HCC patients

| Variable | Bone metastasis | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (≤56 versus > 56 years) | 0.725(0.286–1.840) | 0.499 |

| Gender (male versus female) | 1.864(0.539–6.445) | 0.325 |

| HBsAg (negative versus positive) | 1.849(0.425–8.047) | 0.412 |

| HCV-Ab (negative versus positive) | 1.707(0.227–12.838) | 0.603 |

| AFP, ng/mL (≤ 20 versus > 20) | 1.612(0.574–4.526) | 0.364 |

| ALT,U/L (≤ 40 versus > 40) | 0.255(0.034–1.915) | 0.184 |

| γ-GT,U/L (≤ 50 versus > 50) | 1.032(0.400–2.662) | 0.949 |

| Liver cirrhosis (no versus yes) | 4.662(0.620–35.039) | 0.135 |

| Child-Pugh score (A versus B) | 1.155(0.153–8.697) | 0.889 |

| Tumor differentiation (I–II versus III–IV) | 1.504(0.597–3.789) | 0.387 |

| Tumor size, cm (≤ 5 versus > 5) | 0.657(0.216–1.996) | 0.458 |

| Tumor number (single versus multiple) | 0.963(0.373–2.486) | 0.937 |

| Tumor encapsulation (complete versus none) | 1.079(0.426–2.737) | 0.872 |

| Vascular invasion (no versus yes) | 10.054(3.572–28.302) | < 0.001 |

| BCLC stage (0-A versus B-C) | 7.193(2.361–21.919) | 0.001 |

| Lnc34a (low versus high) | 5.385(1.558–18.612) | 0.008 |

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV-Ab hepatitis C virus antibody, AFP a-fetoprotein, ALT alanine aminotransferase, γ-GT γ-glutamyl transferase, BCLC-stage Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with bone metastasis in 157 HCC patients

| Variable | Bone metastasis | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Vascular invasion (no versus yes) | 6.625(2.291–19.157) | < 0.001 |

| BCLC stage (0-A versus B-C) | 3.910(1.244–12.287) | 0.020 |

| Lnc34a (low versus high) | 3.883(1.107–13.629) | 0.034 |

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, BCLC-stage Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage

Discussion

Bone metastasis occurred in 25.5 to 38.5% of HCC patients with extrahepatic metastases [26] and in 11.7% of HCC patients after hepatectomy [23].The recurrent skeletal-related events (SREs) such as pain and fractures, severely affected the prognosis and quality of life of HCC patients [3]. Early prediction or detection of bone metastases is urgently needed in clinical practice to identify the best treatment for patients at high risk of bone metastasis and avoid the subsequent complications.

The search for specific disease-related biomarkers in patient samples including tissues and body fluids through molecular biology techniques is known as molecular diagnostics [27]. The use of biomarkers could contribute to early diagnosis of cancer, monitoring of disease, as well as the response of therapy, substantially improving patients’ survival rates and quality of life [27]. Our previous study has found that intratumoral connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression, interleukin-11 (IL-11) expression and the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) chemokine receptor may serve as useful predictive biomarkers for bone metastasis in HCC patients [23, 28]. We previously established a predictive model incorporating the tumor properties of vascular invasion and TNM stage, and CXCR4, CTGF, and IL-11 proteins to predict bone metastasis in HCC [29].

However, tissue biopsies are clinically unfeasible for some patients [9]. Tissue biopsies are invasive examinations which may cause substantial complications in patients through biopsies or needle aspirations [30]. While liquid biopsy is a non-invasive procedure and allows for repeat sampling in serum, plasma or saliva [31, 32], which would be useful for numerous diagnostic and monitoring applications in cancer patients with advanced-stage, as is the case for bone metastases [33]. It can detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating free DNA (cfDNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), or microRNA (miRNA) which are released into the bloodstream by cancer cells [31]. Up to date, genome sequencing studies have identified that increased level of circulating lncRNAs has been observed in the blood of patients with cancer. LncRNAs becomes emerging in the search of novel biomarkers for diagnostics or prognostics in cancer due to its greater tissue specificity compared with protein-coding mRNAs [34]. For instance, the upregulated LINC00161 in serum samples of HCC patients was useful for early diagnosis of HCC [35]. A three-lncRNA panel (PCAT-1, UBC1 and SNHG16) in serum exosomes may serve as valuable diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of bladder cancer [36]. What’s more, Duan, W et al. (2016) have confirmed that serum lncRNAs are very stable even incubated for a long time at room temperature or at − 80 °C and repeated freeze-thaw cycles [37]. The highly stability of circulating cell-free lncRNA may due to the protection by extracellular vesicles including exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies and the combination with protein or other chromatin remodeling complexes [37, 38].

Nowadays, lncRNAs have played an emerging role in bone metastasis of other cancers. Liu, M et al. demonstrated MALAT1 was significantly highly expressed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues with bone metastasis and in NSCLC cell lines with high bone metastatic ability [39]. Li C et al. (2017) suggest that ROR1-HER3-LncRNA(MAYA) signaling axis modulates the Hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis and serves as a promising therapeutic target for bone metastasis [40]. Liu P et al. (2018) indicated that LINC00852 promotes lung adenocarcinoma spinal metastasis by targeting S100A9 [41]. Although lncRNAs have played an emerging role in bone metastasis from other cancers, there are no studies assessing serum lncRNAs in cancer patients with bone metastasis.

Lnc34a was first discovered by Wang et al. [19] (2016). They originally wanted to identify what decreases miR-34a expression in the bowel cancer cells. Then they discovered the potential transcripts within miR-34a promoter region by RT-PCR with 10 pairs of primers and continued to amplify a 293 bp transcript fragment. Finally, a new long non-coding RNA molecule, named lnc34a with a full-length of 693 bp transcript, was identified by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and further confirmed by norther blot assay in colorectal cancer cell lines and colon cancer stem cell lines. The uneven distribution of lnc34a in colon cancer cells division suppressed miR-34a expression in one of the daughter cells and then sped up cells division [19]. In the current study, we showed that the expression levels of serum lnc34a in patients with bone metastases were significantly higher than those without bone metastases. Analysis revealed that patients with high serum lnc34a expression were more likely to exhibit high rates of vascular invasion and advanced BCLC stage. In addition, correlation analysis revealed that lnc34a expression was significantly correlated with HCC bone metastases. Univariate and multivariate analysis identified that serum expression of lnc34a, vascular invasion and BCLC stage were significantly associated with bone metastasis. Besides, we determined that lnc34a expression levels were specifically associated bone metastasis rather than lung or lymph node metastasis. Our findings suggest that circulating lnc34a, vascular invasion and BCLC stage were independent risk factors for bone metastases in HCC patients. With the lnc34a expression, vascular invasion and BCLC stage, HCC patients were divided into low- or high-risk groups for bone metastasis. Therefore, HCC patients at high risk of bone metastases can be identified by analyzing circulating lnc34a expression and other clinicopathological factors. The prophylactic treatment such as oral clodronate, could be taken for the HCC patients who are at a high risk for bone metastasis to reduce the frequency and severity of skeletal complications. However, there are certain limitations in our study. This was a retrospective study and the population of enrolled patients was relatively small. In the future, more large-scale studies are needed to further confirm our findings. A detailed mechanism of how lnc34a affects HCC tumors cells and spread to bone should be further investigated.

Conclusions

Based on the results of our study, the expression levels of serum lnc34a in HCC patients with bone metastases were significantly higher than those without bone metastases. Therefore, circulating lnc34a, vascular invasion and BCLC stage were independent risk factors for bone metastases in HCC patients.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary figure 1. ROC curves analysis of lnc34a expession.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- lncRNAs

Long noncoding RNAs

- ESCC

Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- DCP

Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin

- CCSC

Colon cancer stem cells

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCV-Ab

Hepatitis C virus antibody

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- γ-GT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- SREs

Skeletal-related events

- CTCs

Circulating tumor cells

- cfDNA

Circulating free DNA

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

Authors’ contributions

ZCZ and ZLX conceived and designed the study. The serum samples were collected by PY. Data acquisition was carried out by JM and BYY. LZ and HN conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. LZ drafted the manuscript. Revision of the manuscript was done by HN, ZCZ and ZLX. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by sponsored by Shanghai Sailing Program (Grant No. 20YF1405500, 20YF1405600), the Youth Programme of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Grant No. 2020ZSQN24), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81773220, 81960525) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant No.17ZR1405300), Science and the Technology supporting project of Shanghai (Grant No.17411962600), Science and the Technology innovation project of Shanghai (Grant No.19DZ1930900), Science and Technology Development Fund of Pudong New Area Shanghai (Grant No. PKJ2018-Y02), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi (Grant No. 20192BAB205071), and Shanghai municipal human resources and social security bureau (Grant No.Q2016–019). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Additional data/files would be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent Written informed consent was obtained from all Participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Zhang and Hao Niu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zhao-Chong Zeng, Email: zeng.zhaochong@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Zuo-Lin Xiang, Email: xiangzuolinmd@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;91(10127):1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo V, Brunetti O, D'Oronzo S, Ostuni C, Gatti P, Silvestris F. Bone metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma: an emerging issue. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33(1):333–342. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M, Izumi N, Ichida T, Kudo M, et al. Comparison of resection and ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study based on a Japanese nationwide survey. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uchino K, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Kanda M, Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: clinical features and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2011;117(19):4475–4483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He J, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, Zhou J, Zeng MS, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma receiving external beam radiotherapy. Cancer. 2009;115(12):2710–2720. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva A, Bullock M, Calin G. The clinical relevance of long non-coding RNAs in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7(4):2169–2182. doi: 10.3390/cancers7040884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reis EM, Verjovski-Almeida S. Perspectives of long non-coding RNAs in Cancer diagnostics. Front Genet. 2012;3:32. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowley E, Di Nicolantonio F, Loupakis F, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(8):472–484. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsui NB, Ng EK, Lo YM. Stability of endogenous and added RNA in blood specimens, serum, and plasma. Clin Chem. 2001;48(10):1647–1653. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/48.10.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iempridee T, Wiwithaphon S, Piboonprai K, Pratedrat P, Khumkhrong P, Japrung D, et al. Identification of reference genes for circulating long noncoding RNA analysis in serum of cervical cancer patients. FEBS Open Bio. 2018;8(11):1844–1854. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang LJ, Wang Y, Chen J, Wang Y, Zhao YB, Wang YL, et al. Long noncoding RNA PCAT1, a novel serum-based biomarker, enhances cell growth by sponging miR-326 in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(7):513. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1745-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Li Y, Song HQ, Sun GW. Long non-coding RNA LINC00899 as a novel serum biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis prediction of acute myeloid leukemia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(21):7364–7370. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201811_16274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang JY, Wang SY, Lin Y, Yi HC, Niu JJ. The Diagnostic Performance of lncRNAs from Blood Specimens in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Lab Med. 2020:lmaa050. 10.1093/labmed/lmaa050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Yao Z, Jia C, Tai Y, Liang H, Zhong Z, Xiong Z, et al. Serum exosomal long noncoding RNAs lnc-FAM72D-3 and lnc-EPC1-4 as diagnostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(12):11843–11863. doi: 10.18632/aging.103355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YR, Kim G, Tak WY, Jang SY, Kweon YO, Park JG, et al. Circulating exosomal noncoding RNAs as prognostic biomarkers in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(6):1444–1452. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaker OG, Abdelwahed MY, Ahmed NA, Hassan EA, Ahmed TI, Abousarie MA, et al. Evaluation of serum long noncoding RNA NEAT and MiR-129-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma. IUBMB Life. 2019;71(10):1571–8. doi: 10.1002/iub.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZF, Hu R, Pang JM, Zhang GZ, Yan W, Li ZN. Serum long noncoding RNA LRB1 as a potential biomarker for predicting the diagnosis and prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(2):1593–1601. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Bu P, Ai Y, Srinivasan T, Chen HJ, Xiang K, et al. A long non-coding RNA targets microRNA miR-34a to regulate colon cancer stem cell asymmetric division. Elife. 2016;5:e14620. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzeszinski JY, Wei W, Huynh H, Jin Z, Wang X, Chang TC, et al. miR-34a blocks osteoporosis and bone metastasis by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and Tgif2. Nature. 2014;512(7515):431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Maroni P, Puglisi R, Mattia G, Carè A, Matteucci E, Bendinelli P, et al. In bone metastasis miR-34a-5p absence inversely correlates with met expression, while met oncogene is unaffected by miR-34a-5p in non-metastatic and metastatic breast carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38(5):492–503. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Niu H, Ma J, Yuan BY, Chen YH, Zhuang Y, et al. The molecular mechanism of LncRNA34a-mediated regulation of bone metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, He J, Zeng HY, et al. Potential prognostic biomarkers for bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2011;16(7):1028–1039. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu L, Ding J, Chen C, Wu ZJ, Liu B, Gao Y, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncARSR promotes Sunitinib resistance in renal Cancer by acting as a competing endogenous RNA. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(5):653–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu XD, Zhang JB, Zhuang PY, Zhu HG, Zhang W, Xiong YQ, et al. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2707–2716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harding JJ, Abu-Zeinah G, Chou JF, Owen DH, Ly M, Lowery MA, et al. Frequency, morbidity, and mortality of bone metastases in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16(1):50–58. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arantes L, De Carvalho AC, Melendez ME, Carvalho AL. Serum, plasma and saliva biomarkers for head and neck cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018;18(1):85–112. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2017.1404906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, Zhuang PY, Liang Y, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma patients increases the risk of bone metastases and poor survival. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Fan J, Wu WZ, He J, Zeng HY, et al. A clinicopathological model to predict bone metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137(12):1791–1797. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer CA, Schafer JJ, Yakob M, Lima P, Camargo P, Wong David TW. Saliva diagnostics: utilizing oral fluids to determine health status. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;24:88–98. doi: 10.1159/000358791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaczor-Urbanowicz KE, Martin CC, Kaczor T, Tu M, Wei F, Garcia-Godoy F, et al. Emerging technologies for salivaomics in cancer detection. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(4):640–647. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorgannezhad L, Umer M, Islam MN, Nguyen NT, Shiddiky Muhammad JA. Circulating tumor DNA and liquid biopsy: opportunities, challenges, and recent advances in detection technologies. Lab Chip. 2018;18(8):1174–1196. doi: 10.1039/C8LC00100F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, Biggs H, Rueda OM, Chin SF, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25(18):1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun L, Su Y, Liu X, Xu M, Chen XX, Zhu YF, et al. Serum and exosome long non coding RNAs as potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2018;9(15):2631–2639. doi: 10.7150/jca.24978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang SJ, Du LT, Wang LS, Jiang XM, Zhan Y, Li J, et al. Evaluation of serum exosomal LncRNA-based biomarker panel for diagnosis and recurrence prediction of bladder cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(2):1396–1405. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan WL, Du LT, Jiang XM, Wang R, Yan SZ, Xie YJ, et al. Identification of a serum circulating lncRNA panel for the diagnosis and recurrence prediction of bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(48):78850–78858. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohankumar S, Patel T. Extracellular vesicle long noncoding RNA as potential biomarkers of liver cancer. Brief Funct Genomics. 2016;15(3):249–256. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elv058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu MJ, Sun WL, Liu YQ, Dong XH. The role of lncRNA MALAT1 in bone metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2016;36(3):1679–1685. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li CL, Wang SY, Xing Z, Lin AF, Liang K, Song J, et al. A ROR1-HER3-lncRNA signalling axis modulates the hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(2):106–119. doi: 10.1038/ncb3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu P, Wang HL, Liang Y, Hu AN, Xing R, Jiang LB, et al. LINC00852 promotes lung adenocarcinoma spinal metastasis by targeting S100A9. J Cancer. 2018;9(22):4139–4149. doi: 10.7150/jca.26897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary figure 1. ROC curves analysis of lnc34a expession.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Additional data/files would be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.