Abstract

Objective

To describe the place and cause of death during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to assess its impact on excess mortality.

Methods

This national death registry included all adult (aged ≥18 years) deaths in England and Wales between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2020. Daily deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared against the expected daily deaths, estimated with use of the Farrington surveillance algorithm for daily historical data between 2014 and 2020 by place and cause of death.

Results

Between March 2 and June 30, 2020, there was an excess mortality of 57,860 (a proportional increase of 35%) compared with the expected deaths, of which 50,603 (87%) were COVID-19 related. At home, only 14% (2267) of the 16,190 excess deaths were related to COVID-19, with 5963 deaths due to cancer and 2485 deaths due to cardiac disease, few of which involved COVID-19. In care homes or hospices, 61% (15,623) of the 25,611 excess deaths were related to COVID-19, 5539 of which were due to respiratory disease, and most of these (4315 deaths) involved COVID-19. In the hospital, there were 16,174 fewer deaths than expected that did not involve COVID-19, with 4088 fewer deaths due to cancer and 1398 fewer deaths due to cardiac disease than expected.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a large excess of deaths in care homes that were poorly characterized and likely to be the result of undiagnosed COVID-19. There was a smaller but important and ongoing excess in deaths at home, particularly from cancer and cardiac disease, suggesting public avoidance of hospital care for non–COVID-19 conditions.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; MCCD, medical certificate of cause of death; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Globally, as of August 6, 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) accounted for 702,642 deaths.1 In the United Kingdom, this has been evidenced by an abrupt increase in the number of deaths above that expected for the historical average.2 , 3 However, the basis for this excess mortality is poorly defined, with limited information about the causes of death during the pandemic. This is important because although SARS-CoV-2 is known to result in an acute respiratory syndrome for which the highest risk of death is among the elderly and those with preexisting medical conditions,4 , 5 people may have died of other causes as a result of restructuring of medical services during this period or avoidance of health care settings.

Moreover, we and others have reported a dramatic decline in admissions to hospitals with medical emergencies.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Consequent to delays in seeking help for life-threatening illnesses, many deaths are likely to have occurred in the community. Equally, there has been an increase in the number of deaths among those living in care homes.13, 14, 15 Here, the vulnerability of residents to infection as well as changes to health care behavior may have played a role in their death. Should there have been a displacement in the place of death as a result of the pandemic, lessons may be learned to be better prepared in case of a second increase in COVID-19 cases.16

Thus, a systematic characterization of the cause and place of death associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and how this changed compared with the pre-pandemic era is necessary and may offer insights into the susceptibility of the public to the virus as well as the impact of health and public guidance aimed at reducing the spread of the virus. We report the underlying causes of all adult deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in England and Wales, the location of deaths (eg, hospitals, home, or care homes), and their relation to the COVID-19 infection. This information is vital for the understanding of health care policy during the emergence from lockdown and to assist governments around the world in reorganizing health care services now that incident rates of COVID-19 are in decline and social isolation policies are relaxed.

Methods

Data

The analytical cohort included all certified and registered deaths in England and Wales of individuals aged 18 years and older between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2020, recorded in the civil registration of deaths data of the Office for National Statistics of England and Wales.17

Deaths

The primary analysis was based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code corresponding to the underlying cause of death registered as stated on the medical certificate of cause of death (MCCD). The MCCD is completed by the physician who attended the deceased during the last illness within 5 days unless there is to be a coroner’s postmortem examination or an inquest. Underlying causes of death were then categorized as detailed in the Office for National Statistics short list for causes of death17 with additional aggregation of causes for cancer, cardiac diseases, and respiratory diseases (Supplemental Table 1, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). ICD-10 codes U071 (confirmed) and U072 (suspected) listed in any position on the MCCD were used to identify whether a death involved COVID-19 infection. For the purposes of this investigation, the ICD-10 code corresponding to the underlying cause of death was used. Preexisting conditions or other diseases that contributed to but did not directly lead to death were excluded from the analyses. We found that about 1 in 10 MCCDs reported COVID-19 as the underlying cause of death, and for such cases, we used the disease named as directly leading to death to select the underlying cause, which is also the approach taken by the Office for National Statistics.17 The place of death as recorded on the MCCD was classified as home, care home or hospice, and hospital.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics were described with numbers and percentages for categorical data. Data were stratified by COVID-19 status (suspected or confirmed COVID-19 recorded, not mentioned), age band (<50, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80+ years), sex, and place of death. The number of daily deaths was presented using a 7-day simple moving average (the mean number of daily deaths for that day and the preceding 6 days) from February 1, 2020, up to and including June 30, 2020, adjusted for seasonality.

The expected daily deaths from February 1, 2020, up to and including June 30, 2020, were estimated with use of the Farrington surveillance algorithm for daily historical data between 2014 and 2020.18 The algorithm uses overdispersed Poisson generalized linear models with cubic spline terms to model trends in counts of daily death, accounting for seasonality. The number of non–COVID-19 deaths each day from February 1, 2020, was subtracted from the estimated expected daily deaths in the same period to create a zero historical baseline. Deaths above this baseline may be interpreted as excess mortality, calculated as the difference between the observed daily deaths and the expected daily deaths. The proportion of excess deaths was estimated by dividing the excess mortality by the sum of the expected deaths between March 2, 2020, and June 30, 2020. To compare the impact on mortality of the COVID-19 pandemic and the influenza epidemic, information about influenza and pneumonia (ICD-10 code J09-J18) was extracted for the 2 months on either side of the date of the peak death rate each year between 2015 and 2020. The averaged daily deaths during 6 years in the “influenza season” were compared with the averaged daily deaths in the trough period (2 months before and after July 1 each year). All tests were 2 sided, and statistical significance was considered a P value of less than .05. Statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.0.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required as this study used fully anonymized, routinely collected civil registration of deaths data. The data analysis was conducted through remote access to NHS Digital Data Science Server.

Results

Between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2020, there were 3,451,538 deaths due to all causes among adults in England and Wales, of which 224,615 (6.5%) deaths occurred after March 2, 2020 (Table 1). Whereas the hospital remained the most frequent place of death, compared with before March 2, 2020, there were proportionally fewer deaths in the hospital (41% vs 48%) and more in care homes and hospices (33% vs 29%), with similar proportions at home (26% vs 24%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Deaths Before and After March 2, 2020, by COVID-19 Statusa

| Deaths before March 2, 2020 | Non–COVID-19–related deaths after March 2, 2020 | COVID-19–related deaths after March 2, 2020 | Deaths after March 2, 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3,226,923 | 174,012 | 50,603 | 224,615 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1,584,621 (49.1) | 85,594 (49.2) | 27,863 (55.1) | 113,457 (50.5) |

| Female | 1,642,302 (50.9) | 88,418 (50.8) | 22,740 (44.9) | 111,158 (49.5) |

| Age category (y) | ||||

| 18-49 | 136,823 (4.2) | 6444 (3.7) | 995 (2.0) | 7439 (3.3) |

| 50-59 | 183,594 (5.7) | 9934 (5.7) | 2312 (4.6) | 12,246 (5.5) |

| 60-69 | 374,105 (11.6) | 18,932 (10.9) | 4883 (9.6) | 23,815 (10.6) |

| 70-79 | 708,387 (22.0) | 38,886 (22.3) | 11,376 (22.5) | 50,262 (22.4) |

| 80+ | 1,824,014 (56.5) | 99,816 (57.4) | 31,037 (61.3) | 130,853 (58.3) |

| Region | ||||

| North East | 146,146 (5.3) | 9056 (5.2) | 2832 (5.6) | 11,888 (5.3) |

| North West | 374,758 (13.6) | 23,490 (13.5) | 7741 (15.3) | 31,231 (13.9) |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 272,521 (9.9) | 17,214 (9.9) | 4691 (9.3) | 21,905 (9.8) |

| East Midlands | 219,614 (8.0) | 14,050 (8.1) | 3574 (7.1) | 17,624 (7.8) |

| West Midlands | 289,234 (10.5) | 18,692 (10.7) | 5848 (11.6) | 24,540 (10.9) |

| East of England | 291,819 (10.6) | 19,027 (10.9) | 4902 (9.7) | 23,929 (10.7) |

| London | 268,237 (9.7) | 16,851 (9.7) | 8606 (17.0) | 25,457 (11.3) |

| South East | 425,229 (15.4) | 26,591 (15.3) | 7124 (14.1) | 33,715 (15.0) |

| South West | 295,718 (10.7) | 18,778 (10.8) | 2879 (5.7) | 21,657 (9.6) |

| Wales | 169,288 (6.2) | 10,260 (5.9) | 2404 (4.8) | 12,664 (5.6) |

| Place of deathb | ||||

| Home | 760,173 (24.0) | 55,324 (32.5) | 2334 (4.6) | 57,658 (26.2) |

| Care home or hospice | 900,691 (28.5) | 56,179 (33.0) | 15,966 (31.7) | 72,145 (32.7) |

| Hospital | 1,503,836 (47.5) | 58,546 (34.4) | 32,112 (63.7) | 90,658 (41.1) |

| Underlying cause of death | ||||

| Malignant neoplasms | 896,515 (27.8) | 46,932 (27.0) | 1127 (2.2) | 48,059 (21.4) |

| Cardiac diseases | 497,556 (15.4) | 26,230 (15.1) | 1050 (2.1) | 27,280 (12.1) |

| Respiratory diseases | 451,324 (14.0) | 20,769 (11.9) | 19,861 (39.2) | 40,630 (18.1) |

| Dementia and Alzheimer disease | 393,405 (12.2) | 26,168 (15.0) | 1036 (2.0) | 27,204 (12.1) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 199,578 (6.2) | 9734 (5.6) | 441 (0.9) | 10,175 (4.5) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 76,228 (2.4) | 6351 (3.6) | 2718 (5.4) | 9069 (4.0) |

| Diseases of the urinary system | 53,264 (1.7) | 2882 (1.7) | 280 (0.6) | 3162 (1.4) |

| Cirrhosis and other diseases of liver | 50,404 (1.6) | 2820 (1.6) | 116 (0.2) | 2936 (1.3) |

| Diabetes | 36,619 (1.1) | 2631 (1.5) | 164 (0.3) | 2795 (1.2) |

| Parkinson disease | 36,295 (1.1) | 2515 (1.4) | 91 (0.2) | 2606 (1.2) |

| Other cause of diseases | 535,735 (16.6) | 26,980 (15.5) | 1784 (3.5) | 28,764 (12.8) |

| COVID only | — | — | 21,935 (43.3) | 21,935 (9.8) |

Values are reported as number (percentage).

The numbers do not add up to the total deaths because of missingness or unknown place of death (1.9%).

Excess Deaths After March 2, 2020

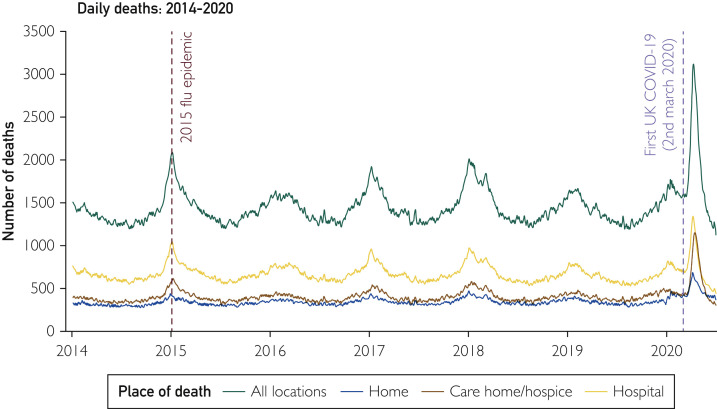

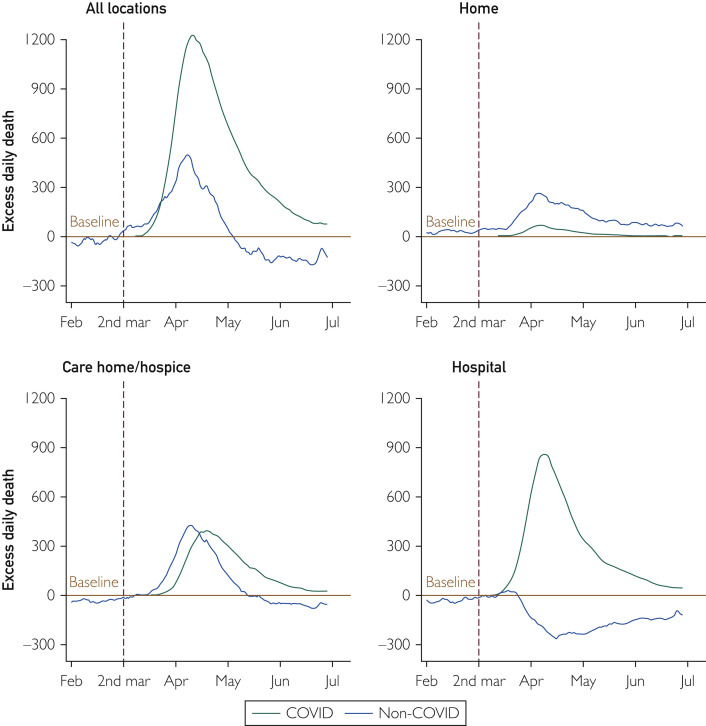

The peak in deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic was much greater than for any of the influenza seasonal peaks in the years between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 1 ). After the first COVID-19 death on March 2, 2020, to June 30, 2020, there was an excess mortality of 57,860 (a proportional increase of 35%) compared with the expected daily deaths estimated by the Farrington surveillance algorithm for daily historical data between 2014 and 2020 (Figure 2 ; Table 2 ). The number of excess deaths was higher for men than for women (29,956, a proportional increase of 36%, vs 27,839, a proportional increase of 33%) and the highest among people older than 80 years (37,244, a proportional increase of 40%; Table 2). London had the largest absolute number of excess deaths (9001 deaths, a proportional increase of 55%). Almost half the excess deaths occurred in care homes and hospices (25,611 deaths), where deaths were 55% higher than expected. One-quarter of the excess deaths occurred in the hospital (15,938 deaths, a proportional increase of 21%), with the remainder occurring at home (16,190 deaths, a proportional increase of 39%; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Times series of daily deaths in England and Wales, 2014 to 2020. The number of daily deaths is presented using a 7-day simple moving average (indicating the mean number of daily deaths for that day and the preceding 6 days). The green line represents daily deaths in all places, the yellow line represents daily deaths in the hospital, the brown line represents daily deaths at care homes and hospices, and the blue line represents daily deaths at home.

Figure 2.

Time series of daily deaths according to COVID-19 by place of death. The number of daily deaths is presented using a 7-day simple moving average (indicating the mean number of daily deaths for that day and the preceding 6 days) from February 1, 2020, up to and including June 30, 2020, adjusted for seasonality. The number of non–COVID-19 excess deaths each day from February 1, 2020, was subtracted from the expected daily death estimated by the Farrington surveillance algorithm in the same period. The brown line is a zero historical baseline. The green line represents daily COVID-19 deaths from March 2 to June 30, 2020; the blue line represents daily non–COVID-19 deaths from March 2 to June 30, 2020.

Table 2.

All and COVID-19–Related Excess Deathsa

| Total expected deaths | COVID-19 related | Excess deaths |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non–COVID-19 relatedb | Total (% change compared with total expected deaths)c | |||

| Total | 168,677 | 50,603 | 7257 | 57,860 (+35%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 84,433 | 27,863 | 2093 | 29,956 (+36%) |

| Women | 84,222 | 22,740 | 5099 | 27,839 (+33%) |

| Age category (y) | ||||

| 18-49 | 6633 | 995 | −13 | 982 (+15%) |

| 50-59 | 10,052 | 2312 | 71 | 2383 (+24%) |

| 60-69 | 18,781 | 4883 | 368 | 5251 (+28%) |

| 70-79 | 37,920 | 11,376 | 641 | 12,017 (+31%) |

| 80+ | 94,052 | 31,037 | 6207 | 37,244 (+40%) |

| Region | ||||

| North East | 9440 | 2832 | −269 | 2563 (+27%) |

| North West | 24,191 | 7741 | −278 | 7463 (+31%) |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 17,374 | 4691 | −81 | 4610 (+27%) |

| East Midlands | 14,296 | 3574 | −296 | 3278 (+23%) |

| West Midlands | 18,275 | 5848 | 324 | 6172 (+33%) |

| East of England | 18,854 | 4902 | 70 | 4972 (+26%) |

| London | 16,550 | 8606 | 395 | 9001 (+55%) |

| South East | 26,385 | 7124 | −98 | 7026 (+26%) |

| South West | 19,193 | 2879 | −230 | 2649 (+14%) |

| Wales | 10,927 | 2404 | −688 | 1716 (+16%) |

| Place of deathd | ||||

| Home | 38,900 | 2334 | 13,856 | 16,190 (+39%) |

| Care home or hospice | 46,959 | 15,966 | 9645 | 25,611 (+55%) |

| Hospital | 74,679 | 32,112 | −16,174 | 15,938 (+21%) |

| Underlying cause of deaths | ||||

| Respiratory diseases | 22,569 | 19,861 | −1636 | 18,225 (+81%) |

| Dementia and Alzheimer disease | 20,720 | 1036 | 4897 | 5933 (+28%) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 4530 | 2718 | 1850 | 4568 (+101%) |

| Cardiac diseases | 26,250 | 1050 | 1175 | 2225 (+9%) |

| Other cause of diseases | 25,486 | 1784 | −219 | 1565 (+6%) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 56,350 | 1127 | −440 | 687 (+1%) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 8820 | 441 | 530 | 971 (+11%) |

| Diabetes | 2050 | 164 | 519 | 683 (+32%) |

| Diseases of the urinary system | 2545 | 280 | 315 | 595 (+23%) |

| Parkinson disease | 2275 | 91 | 453 | 544 (+26%) |

| Cirrhosis and other diseases of liver | 2900 | 116 | 97 | 213 (+8%) |

Excess deaths were derived by comparing daily deaths between March 2 and June 30, 2020, with the expected daily deaths estimated by the Farrington surveillance algorithm for daily historical data between 2014 and 2020.

Non–COVID-19–related excess deaths were derived by subtracting COVID-19–related excess deaths from total excess deaths.

Excess deaths in subgroups may not add up to total excess deaths because of rounding errors in comparison with the historical baseline data.

The numbers do not add up to the total deaths because of missingness (1.9%).

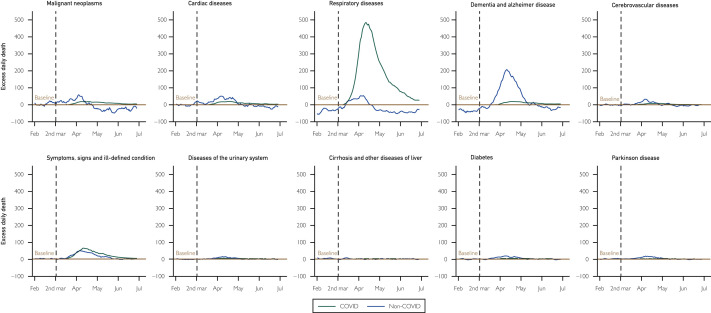

Among the excess deaths, 50,603 (87%) were COVID-19 related (Figure 2; Table 2). There were large numbers of excess deaths caused by respiratory disease (18,225 deaths, a proportional increase of 81%), dementia (5933 deaths [including 1036 related to COVID], a proportional increase of 28%), and ill-defined conditions (4568 deaths [including 2718 related to COVID], a proportional increase of 101%; Figure 3 ; Table 2). There were smaller numbers of excess deaths due to cardiac disease (2225 deaths [including 1050 related to COVID], a proportional increase of 9%) and cancer (687 deaths, a proportional increase of 1% [1127 related to COVID, but 440 fewer cancer deaths than expected after subtracting the COVID-related deaths]; Figure 3; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Time series of daily deaths according to COVID-19 by underlying cause of death. The number of daily deaths is presented using a 7-day simple moving average (indicating the mean number of daily deaths for that day and the preceding 6 days) from February 1, 2020, up to and including June 30, 2020, adjusted for seasonality. The number of non–COVID-19 excess deaths each day from February 1, 2020, was subtracted from the expected daily death estimated by the Farrington surveillance algorithm in the same period. The brown line is a zero historical baseline. The green line represents daily COVID-19 deaths from March 2 to June 30, 2020; the blue line represents daily non–COVID-19 deaths from March 2 to June 30, 2020.

COVID-19–Related Deaths

Between March 2, 2020, and June 30, 2020, there were 50,603 COVID-related deaths, one-quarter of the deaths occurring during this period (Table 1). About two-thirds of the COVID-19–related deaths occurred in the hospital, about one-third occurred in care homes and hospices, and less than 5% occurred at home (Table 1). Of the COVID-19–related deaths, 55% occurred in men and about two-thirds occurred in those aged 80 years or older, with less than 2% occurring in those younger than 50 years. In around half of the COVID-19–related deaths, the condition leading directly to death was recorded as COVID-19 (21,935 deaths) or an ill-defined cause of death (2718 deaths), with a further 39% of COVID-19–related deaths (19,681 deaths) in which a respiratory disease led directly to death (639 involving asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or another chronic lung disease and 18,264 involving respiratory failure or respiratory infection; Table 1). Only 1127 (2%) of the COVID-19–related deaths involved cancer, and 1050 (2%) involved cardiac disease.

Place and Cause of Death After March 2, 2020

Deaths at home increased sharply at the end of March and in early April (Figure 2) and remain above expected levels. Only 14% (2267) of the 16,190 excess deaths occurring at home were related to COVID-19 (Table 2). There were 5963 excess deaths at home due to cancer and 2485 excess deaths due to cardiac disease, very few of which involved COVID-19 (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Excess Deaths by Underlying Cause and Place of Deatha

| Home |

Care home or hospice |

Hospital |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 related | Non–COVID-19 relatedb | Total (% change) | COVID-19 related | Non–COVID-19 relatedb | Total (% change) | COVID-19 related | Non–COVID-19 relatedb | Total (% change) | |

| All-cause | 2334 | 13,856 | 16,190 (+39%) | 15,966 | 9645 | 25,611 (+55%) | 32,112 | −16,174 | 15,938 (+21%) |

| Respiratory diseases | 761 | 1023 | 1784 (+42%) | 4315 | 1224 | 5539 (+169%) | 14,731 | −3845 | 10,886 (+74%) |

| Dementia and Alzheimer disease | 33 | 1063 | 1096 (+45%) | 783 | 5484 | 6267 (+45%) | 219 | −1719 | −1500 (−31%) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 96 | 543 | 639 (+44%) | 1003 | 1355 | 2358 (+90%) | 1610 | −59 | 1551 (+491%) |

| Cardiac diseases | 118 | 2367 | 2485 (+26%) | 211 | 1000 | 1211 (+31%) | 711 | −2109 | −1398 (−13%) |

| Other cause of diseases | 88 | 1451 | 1539 (+26%) | 498 | 718 | 1216 (+33%) | 1193 | −2321 | −1128 (−7%) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 149 | 5814 | 5963 (+40%) | 392 | −1887 | −1495 (−10%) | 573 | −4661 | −4088 (−24%) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 15 | 515 | 530 (+51%) | 96 | 775 | 871 (+39%) | 329 | −788 | −459 (−8%) |

| Diabetes | 17 | 279 | 296 (+52%) | 24 | 284 | 308 (+49%) | 122 | −65 | 57 (+6%) |

| Diseases of the urinary system | 31 | 273 | 304 (+78%) | 61 | 286 | 347 (+66%) | 184 | −255 | −71 (−4%) |

| Parkinson disease | 5 | 205 | 210 (+60%) | 50 | 307 | 357 (+34%) | 36 | −59 | −23 (−3%) |

| Cirrhosis and other diseases of liver | 4 | 184 | 188 (+31%) | 14 | 12 | 26 (+16%) | 98 | −89 | 9 (+0%) |

Excess deaths were derived by comparing daily deaths between March 2 and June 30, 2020, with the expected daily deaths estimated by the Farrington surveillance algorithm for daily historical data between 2014 and 2020.

The number of non–COVID-19–related excess deaths was derived by subtracting the COVID-19–related excess deaths from the total excess deaths.

There were 25,611 excess deaths in care homes and hospices, of which about two-thirds (15,966 deaths) were related to COVID-19 (Figure 2). Of the excess deaths in care homes and hospices, 5539 were due to respiratory disease, and most of these (4315 deaths) involved COVID-19. There were 6267 excess deaths due to dementia and 2358 excess deaths due to ill-defined conditions in care homes or hospices, of which only 783 and 1003, respectively, were recorded as COVID-19 related. There were 1495 fewer deaths in care homes and hospices due to cancer than expected and 1211 excess deaths in care homes due to cardiac disease (Table 3).

In the hospital after March 2, 2020, there were 32,112 COVID-19–related deaths but 16,174 fewer deaths than expected that did not involve COVID-19, meaning that the total number of excess deaths in the hospital was 15,938 (Figure 2; Table 3). There were 4088 fewer deaths in the hospital due to cancer and 1398 fewer deaths in the hospital due to cardiac disease than expected (Table 3).

The time course of changes in deaths by cause and place is shown in Supplemental Figure 1 (available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). At the end of March, there was an increase in deaths due to cancer in homes, with a corresponding fall in cancer deaths below the historical baseline in hospitals (Supplemental Figure 1). These changes in the location of cancer deaths were still present at the end of June. During March and April, deaths due to cardiac disease increased in homes, care homes, and hospices and fell below the historical baseline in hospitals, returning to expected levels in all locations by the end of June. In care homes and hospices, there was a sharp increase at the end of March in deaths due to dementia and Alzheimer disease and from respiratory disease, with a subsequent rapid decline in late April.

Comparison With Seasonal Influenza Epidemics

The numbers of excess deaths due to influenza and pneumonia in previous years occurred with the greatest magnitude in the hospital, an increase of 28% during influenza epidemics compared with a 21% increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (Supplemental Table 2, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org). Of 40,223 excess deaths during influenza epidemics, 12,929 (32%) excess deaths were due to respiratory causes (Supplemental Figure 2, available online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org; Supplemental Table 2). In comparison, 87% of excess deaths were recorded as COVID-19 related during the pandemic (Table 2).

Discussion

We report, for the first time, in a complete analysis of all adult deaths in England and Wales, the extent, site, and underlying causes of the increased mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous years. This shows that most of the 58,000 excess deaths during this period involved COVID-19, and in most of these, COVID-19 appeared to be the direct cause of death. However, there was a substantial increase in the absolute numbers of deaths occurring at home, especially due to cancer and cardiac disease, whereas deaths due to these causes in the hospital were lower than expected. In care homes and hospices, there was an abrupt increase in the absolute numbers of deaths due to dementia, Alzheimer disease, and ill-defined causes in addition to COVID-19–related deaths.

We found evidence for the displacement in the place of death from the hospital to the community setting during the pandemic. In England and Wales, almost half of all adult deaths historically occurred in the hospital, but during the pandemic, only a quarter did. During the pandemic, about 26,000 excess deaths (almost half of the total excess deaths) occurred in care homes and hospices. Residents of care homes frequently died of respiratory disease (mostly involving COVID-19) but also of “symptoms and signs of ill-defined conditions” (which typically indicates old age and frailty18) and dementia and Alzheimer disease. Although it is not possible to be certain about the factors leading to the substantial excess in deaths due to these less well defined causes, undiagnosed COVID-19 is likely.

The efficient person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2,19 its asymptomatic incubation and transmission period,20 , 21 and its propensity to death in the elderly and people with comorbid conditions will have been major contributing factors to the excess mortality in care homes. In March 2020, a report detailing an outbreak of COVID-19 infection at a long-term care center that was associated with high mortality rates recommended proactive steps by such places to identify and to exclude potentially infected staff and visitors and to implement infection prevention and control measures to reduce the introduction of the virus to residents.22 Yet, in the United Kingdom, patients were discharged without information of their infective status from hospitals to care homes, where the virus could easily spread13 and actions to effectively reduce the spread of the virus in social care were not implemented early in the pandemic.23 Early in the pandemic, testing of suspected cases was available only in the hospital, whereas routine testing of staff and residents in care homes was not implemented until May 2020,24 potentially leading to underdiagnosis of COVID-19.25 In addition, it is possible that care home residents who became unwell during the pandemic were not referred to or decided not to go to the hospital for fear of becoming infected, a notion that aligns with the substantial reduction in hospital attendances for medical emergencies following the lockdown in the United Kingdom.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Most of the deaths in the hospital involved COVID-19. After exclusion of the COVID-19–related deaths, there were fewer deaths than expected for cancer, cardiac disease, cerebrovascular disease, and dementia and Alzheimer disease in the hospital. This finding supports the concept of patients with non–COVID-19 illness staying in the community rather than attending hospital. Other possible explanations include factors related to the redeployment of front-line staff and the cancellation of procedures,26 undermining routine care and the use of alternative levels of treatment, as well as earlier discharge back to the community.

At home, the largest number of excess deaths was due to cardiac disease and cancer, and few deaths involved COVID-19. This may be explained by infection’s serving as a trigger to acute decompensation of a preexisting disease27 (and which may be underreported because of nonsystematic testing28), but it is more likely to be related to a reluctance by the public to attend hospital when unwell because of fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2. Another possible explanation is that early in the course of the pandemic, hospitals prepared for a potential mass influx of patients by expeditious hospital discharge of inpatients to the community, which may have resulted in a number of deaths.

This study assessed the excess deaths only during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the infection was better controlled and hospital pressure eased during the summer, the excess deaths were fewer or returned to normal, as shown by a plateauing of the excess curves toward July 2020. As winter approached and infection rates increased during the second wave of the pandemic, there was a similar pattern of excess deaths.14

Whereas previous reports have described an elevated risk of death among the elderly and people with cardiovascular disease during the COVID-19 pandemic, none have characterized the underlying causes and place of death in an unselected national cohort.5 , 29 , 30 It is nonetheless plausible that similar findings of excess and translocated deaths have occurred in other countries. Whereas decisions about care unique to the United Kingdom may have been associated with an inflation in deaths in the community (and nursing homes), others have reported an increase in community deaths,31 , 32 suggesting that a number of factors are at play.

The unique strengths of this investigation include full population coverage of all adult deaths across all places of death. Nonetheless, our study has limitations. First, during the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency guidance enabled any physician in the United Kingdom (not just the attending physician) to complete the MCCD, the duration of time for which the deceased was not seen before referral to the coroner was extended from 14 to 28 days, and causes of death could be “to the best of their knowledge and belief” without diagnostic proof, if appropriate and to avoid delay.33 This may have resulted in inaccurate recording of cause of death. Second, this analysis will have excluded a small proportion of deaths under review by the coroner, although typically these will have been unnatural in etiology. Third, we did not have access to laboratory testing data. It is estimated that methods identifying COVID-19 deaths using laboratory testing data have identified about an additional 1500 deaths during the pandemic period compared with death certificate methods. However, this would explain only a tiny proportion of the non–COVID-19 excess deaths observed in this study.34

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in major global changes to society and health care. These analyses raise important findings for government and the National Health Service. A huge burden of excess deaths occurred in care homes that were poorly characterized and were likely to be, at least in part, the result of undiagnosed COVID-19. Effective assessment and testing along with adequate staffing and infection control measures in care homes should be a priority in the event of a second rise in cases. Second, there was a smaller but important and ongoing excess in deaths at home, particularly deaths due to cancer and cardiac disease, which suggests avoidance of hospital care for non–COVID-19 conditions. Clear public messaging encouraging patients to seek medical advice when necessary along with a robust strategy to maintain COVID-19–free areas within hospitals is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Chris Roebuck, Tom Denwood, Tony Burton, and Courtney Stephenson and data support staff at NHS Digital for providing and creating the secure environment for data hosting and for analytical support. The authors acknowledge Ben Humberstone at the Office for National Statistics for providing the civil registration of deaths in England and Wales and taking responsibility for the integrity of these data. The authors acknowledge Professor Colin Baigent from University of Oxford for constructive suggestion.

The program was endorsed by the British Heart Foundation collaborative, which also includes Health Data Research UK, HSC Public Health Agency, National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, Cancer Research UK, Public Health Scotland, NHS Digital, SAIL Databank, and UK Health Data Research Alliance.

Footnotes

Grant Support: J.W. and C.P.G are funded by the University of Leeds. M.A.M. is funded by the University of Kentucky. The funding organizations for this study had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

Data Previously Presented: A preliminary report of this work was previously published on medRxiv, August 14, 2020.

Data Sharing: The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care has issued a time-limited Notice under Regulation 3(4) of the National Health Service (Control of Patient Information Regulations) 2002 to share confidential patient information. The co-authors are not permitted to share the data.

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Coronavirus tracked: see how your country compares. https://ig.ft.com/coronavirus-chart/?areas=usa&areas=gbr&areas=bra&areasRegional=usny&areasRegional=usca&areasRegional=usfl&areasRegional=ustx&cumulative=0&logScale=1&perMillion=0&values=deaths

- 3.Deaths involving COVID-19, England and Wales: deaths occurring in May 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19englandandwales/latest Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 4.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [erratum appears in Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1038] Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee A., Pasea L., Harris S. Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1715–1725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon M.D., McNulty E.J., Rana J.S. The Covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health England Emergency department syndromic surveillance system bulletin. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886455/EDSSSBulletin2020wk20.pdf Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 8.Kansagra A.P., Goyal M.S., Hamilton S., Albers G.W. Collateral effect of Covid-19 on stroke evaluation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):400–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2014816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollmann A., Hohenstein S., Meier-Hellmann A., Kuhlen R., Hindricks G. Emergency hospital admissions and interventional treatments for heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias in Germany during the Covid-19 outbreak. Insights from the German-wide Helios hospital network. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6(3):221–222. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mafham M.M., Spata E., Goldacre R. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):381–389. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J., Mamas M., Rashid M. Patient response, treatments and mortality for acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020 Jul 30:qcaa062. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa062. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J., Mamas M.A., de Belder M.A. Second decline in admissions with heart failure and myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Jan 12 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.039. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver D. Let's be open and honest about covid-19 deaths in care homes. BMJ. 2020;369:m2334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales, provisional: week ending 17 January 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregisteredweeklyinenglandandwalesprovisional/latest#deaths-registered-by-place-of-occurrence Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 15.Comas-Herrera A., Zalakaín J., Litwin C., Hsu A.T., Lane N., Fernández J. Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Mortality-associated-with-COVID-26-April-1.pdf Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 16.Oliver D. Preventing more deaths in care homes in a second pandemic surge. BMJ. 2020;369:m2461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office for National Statistics User guide to mortality statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/methodologies/userguidetomortalitystatisticsjuly2017 Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 18.Noufaily A., Enki D.G., Farrington P., Garthwaite P., Andrews N., Charlett A. An improved algorithm for outbreak detection in multiple surveillance systems. Stat Med. 2013;32(7):1206–1222. doi: 10.1002/sim.5595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y., Li L. SARS-CoV-2: virus dynamics and host response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):515–516. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavezzo E., Franchin E., Ciavarella C. Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vò [erratum appears in Nature. 2021;590(7844):E11] Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7821):425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin S. Covid-19: "staggering number" of extra deaths in community is not explained by covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coronavirus (COVID-19): care home support package. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-support-for-care-homes/coronavirus-covid-19-care-home-support-package Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 25.Raleigh V.S. Tackling UK's mortality problem: covid-19 and other causes. BMJ. 2020;369:m2295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed M.O., Banerjee A., Clarke S. Impact of COVID-19 on cardiac procedure activity in England and associated 30-day mortality. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020 Oct 20:qcaa079. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa079. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iacobucci G. Covid-19: lack of capacity led to halting of community testing in March, admits deputy chief medical officer. BMJ. 2020;369:m1845. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deaths involving COVID-19, England and Wales: deaths occurring in April 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19englandandwales/deathsoccurringinapril2020#pre-existing-conditions-of-people-who-died-with-covid-19 Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 30.Docherty A.B., Harrison E.M., Green C.A. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballotari P., Guarda L., Giacomazzi E., Ceruti A., Gatti L., Ricci P. [Excess mortality risk in nursing care homes before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Mantua and Cremona provinces (Lombardy Region, Northern Italy)] Epidemiol Prev. 2020;44(5-6, suppl 2):282–287. doi: 10.19191/EP20.5-6.S2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnett M.L., Hu L., Martin T., Grabowski D.C. Mortality, admissions, and patient census at SNFs in 3 US cities during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(5):507–509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Office for National Statistics Guidance for doctors completing medical certificates of cause of death in England and Wales. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/877302/guidance-for-doctors-completing-medical-certificates-of-cause-of-death-covid-19.pdf Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 34.The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine COVID-19 deaths in England and Wales: resolving discrepancies in deaths outside of hospital. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/covid-19-deaths-in-england-and-wales-resolving-discrepancies-in-deaths-outside-of-hospital/ Accessed August 6, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.