Abstract

Introduction

Vape shops represent prominent, unique retailers, subject to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation in the United States.

Aims and Methods

This study assessed compliance of US vape shop retail marketing strategies with new regulations (eg, required age verification, prohibited free samples) and pre-implementation conditions for other regulations (eg, health warning labels on all nicotine products, required disclosures of e-liquid contents).

Results

95.0% of shops displayed minimum-age signage; however, mystery shoppers were asked for age verification at 35.6% upon entry and at 23.4% upon purchase. Although 85.5% of shops had some evidence of implementing FDA health warnings, 29.1% had signage indicating prohibited health claims, 16.3% offered free e-liquid samples, 27.4% had signage with cartoon imagery, and 33.3% were within two blocks of schools. All shops sold open-system devices, 64.8% sold closed-system devices, 68.2% sold their own brand of e-liquids, 42.5% sold e-liquids containing cannabidiol, 83.2% offered price promotions of some kind, and 89.9% had signage for product and price promotions.

Conclusions

Results indicated that most shops complied with some implementation of FDA health warnings and with free sampling bans and minimum-age signage. Other findings indicated concerns related to underage access, health claims, promotional strategies, and cannabidiol product offerings, which call for further FDA and state regulatory/enforcement efforts.

Implications: .

Current and impending FDA regulation of vaping products presents a critical period for examining regulatory impact on vape shop marketing and point-of-sale practices. Findings from the present study indicate that vape shops are complying with several regulations (eg, minimum-age signage, FDA health warnings, free sampling bans). However, results also highlight the utility of mystery shoppers in identifying noncompliance (eg, age verification, health claims, sampling, cannabidiol product offerings). This study provides baseline data for comparison with future surveillance efforts to document the impact of full implementation of the FDA regulations on vape shop practices and marketing.

Introduction

Over the past decade, e-cigarettes emerged globally.1 E-cigarettes may deliver fewer harmful chemicals than traditional cigarettes and potentially support cessation efforts.2–4 However, e-cigarettes contain chemicals that may increase risks of addiction and disease (eg, cardiovascular, lung, pulmonary, cancer).5 Moreover, youth e-cigarette use—or vaping—is a major public health concern.6 As of November 2019, there were 2172 vaping-related lung injury cases and 42 deaths in the United States.7

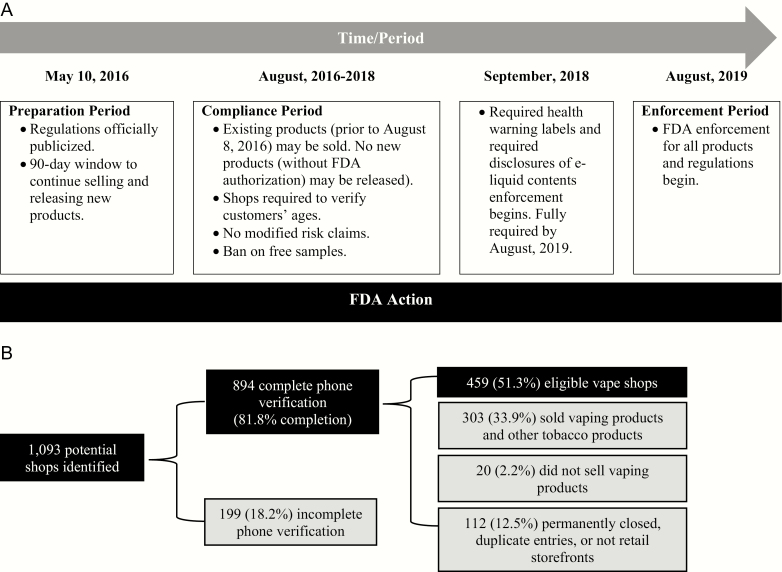

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has regulatory authority over tobacco product manufacturing, distribution, and marketing (eg, packaging, labeling, advertising), as well as cessation pharmacotherapy including nicotine replacement therapy. In 2016, FDA finalized a rule extending its authority beyond cigarettes to all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes (or vaping products).8Figure 1a details select regulatory actions and implementation timeline; important components include minimum-age requirements, health warning labels, and prohibiting free samples.

Figure 1.

FDA tobacco regulation timeline and vape shop identification flowchart. (a) FDA tobacco regulation timeline for select policies; (b) vape shop identification flowcharts. Source: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/compliance-enforcement-training/pipe-cigar-and-vape-shops-are-regulated-both- retailers-and-manufacturers.

In the United States and globally, there has been an expansion of vape shops (ie, tobacco specialty stores that predominately sell vaping devices and nicotine e-liquids but not conventional tobacco products).9 FDA does not require federal licenses to sell tobacco/nicotine products, and its vape shop registry is limited to manufacturers.10 However, one estimate indicated 9945 vape shops in the United States as of December 2015, a nearly threefold increase from 2013; 11 newer estimates have not been published.

Whereas other retail settings (eg, convenience stores) typically sell select closed systems (ie, devices with e-liquid included), vape shops sell many other devices, including open systems that consumers fill with e-liquids, herbal/dry chamber vaporizers, and wet/dry vaporizers.9 Particularly relevant, some more advanced vaping devices may be effective in supporting smoking cessation.12 Vape shops also feature various accessories and e-liquid flavors9 (critical in consumer appeal13) and some promoted experimenting and socializing at tasting bars.9,14

Vape shops use various marketing strategies (eg, product advertising, price promotions).15 Such strategies expand tobacco markets, attract new users, promote continued use, and build brand loyalty.16–18 Advertising can influence how and why consumers vape9,19,20 (eg, perceived safety or cessation utility,14,19–21 social/entertainment value, achieve a “buzz” 19,20). With concern for youth appeal, the FDA issued warnings to manufacturers, distributors, and retailers for selling e-liquids with advertising/labeling with cartoon-like imagery in 201822 and is in the process of banning certain e-liquid flavors.23 Vape shops also market via social media,15 which may promote youth exposure to vaping imagery and advertising.8

FDA regulations may uniquely affect vape shops.24 Free sampling, including those historically offered at vape shop tasting bars,14,25 is no longer allowed under the new federal regulations. Health warnings are required on all products/ads, particularly relevant given that vaping has been endorsed for cessation or harm reduction.14,26 FDA regulation also requires minimum-age signage and age verification to enter vape shops and to purchase tobacco products for those ≤27 years old. This is important given that young adults represent a large vape shop market segment,25 many vape shops (15–27%14,27,28) have no minimum-age signage, and vape shops often allow minors to enter.25

Another relevant consideration is marijuana, given the high rates of marijuana-tobacco co-use29,30 and the growing market for retail marijuana in 10 states and the District of Columbia that legalized recreational use by 2018. Vape shops may carry products (eg, devices, e-liquids) that facilitate vaping cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol. FDA regulations regarding tobacco products do not specify oversight of CBD, but tetrahydrocannabinol products are not legal for sale in vape shops.31,32 States with recreational marijuana laws have designated regulatory oversight of marijuana, which may increase barriers to vape shops offering such products and/or may have social norms more conducive to using marijuana in general and via vaping; not having such laws may deter marijuana use or lead consumers to pursue more discrete ways to use marijuana such as through vaping.33

This study addresses critical gaps in the literature, advances methodological approaches for assessing licit drug retail, and enhances the evidence base regarding vape shop retail. Specifically, we examined compliance of US vape shop retail marketing strategies with new regulations (eg, required age verification, prohibited free samples) and pre-implementation conditions for other regulations (eg, health warning labels on nicotine products, required disclosures of e-liquid contents). Limited research addresses point-of-sale practices of vape shops. Two surveillance methods are point-of-sale audits14,28 and “mystery shopper” approaches.34,35 An extensive literature uses point-of-sale audits to characterize traditional tobacco,36 and a literature on vape shop audits has emerged in the past 6 years.36,37 Mystery shoppers have been used to examine age verification in tobacco and alcohol retail,34,35 but are relatively new to vape shop surveillance. Used in combination, these two approaches may yield important new findings about vape shop retail practices. In particular, mystery shoppers can assess factors missed by traditional point-of-sale surveillance, including actual age verification and characterizing communication from shop personnel about cessation and product safety, which may be inaccurate or countermand FDA’s requirements for modified-risk tobacco products, and therefore could undermine tobacco control efforts. Additionally, prior US vape shop surveillance efforts have not typically assessed availability of nontobacco products. Examining whether vape shops offer marijuana-related products is novel and relevant to state regulation.

Methods

Study Settings

We selected six metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs)—Atlanta, Boston, Oklahoma City, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Seattle, and San Diego—representing geographic diversity and a gradient of tobacco control (eg, excise taxes, smoke-free air), vaping-related policies,10 and marijuana legislation. For example, California and Minnesota tax vaping products; California, Minnesota, and Washington require licenses for vaping product retail sales; California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Washington regulate vaping product packaging10; and California, Colorado, and Washington had legalized recreational marijuana use at time of assessment.

Sample

We adapted procedures from previous research to identify vape shops in the six MSAs.38,39 We searched “vaporizer store” on Google and “vape shops” on Yelp13 to identify stores in the six states tagged by retailers or customers as vape shops. After restricting lists to stores with complete addresses, we linked Google and Yelp records based on address, eliminated duplicate entries within and between sources, reviewed (hand-cleaned) records, and geocoded records to latitude/longitude using ArcGIS v10.1 (mapping rate 100%), yielding 1093 likely vape shops across MSAs.

We used a telephone protocol to confirm that stores met our definition of vape shop (ie, sold vape products but not other tobacco products). Of the 894 retailers from Google/Yelp searches with completed phone verifications, 51.3% (n = 459) met our definition of vape shop (Figure 1b). Roadway distances between these 459 stores and the MSA centroid were computed, and 30 vapes shops within 25 miles of the MSA centroid were randomly selected. The remainder of shops within 25 miles were randomly listed as replacements to be assessed if the initial 30 were not open, out of business, or declined participation.

Data Collection

In May–July 2018, data collection was conducted in Atlanta, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle, Boston, and Minneapolis-St. Paul, respectively. Data collectors were six paid MPH student research staff (ages 23–25, five female) and were perceived to be under the FDA age threshold of 27 years old. Each vape shop was visited twice. First, mystery shopper assessments were conducted by individual staff. Separately, one to three days later, point-of-sale audits were conducted by a pair of trained researchers who gained permission to collect data. No data collector participated in both tasks. Data were recorded via assessment forms programmed in surveygizmo.com and downloaded on iPads. All questions offered check boxes for response options and open fields for notes.

Of the initially selected 180 shops, mystery shopper assessments were completed in 176 and point-of-sale audits in 163 (non-completion due to: not meeting definition of vape shop, n = 1; not open at assessment, n = 2; and research staff asked to leave, n = 14). Following assessment in replacement shops, data collectors completed 196 mystery shopper tasks and 179 point-of-sale audits. Current analyses focus on vape shops where point-of-sale assessments occurred (n = 179) and included data from the mystery shopper assessments that coincided (n = 174).

Mystery Shopper Assessment

Two research staff (23 years old) conducted mystery shopper assessments, adapting previously used strategies.34,40 Single staff entered each vape shop without identifying him/herself as research staff to vape shop personnel or customers. If asked for age verification, he/she presented his/her real ID. If not, he/she assessed whether age verification was requested at purchase. In the interim, the mystery shopper referred to a soft script (to facilitate replication and allow adaptability during assessments) and asked whether vaping (1) is safe and (2) could help him/her or could help “a friend who smoked” quit smoking. Whether the mystery shopper presented him/herself as a “smoker” or “nonsmoker” was determined by coin tosses prior to entry. After assessments (duration 5–25 minutes), mystery shoppers immediately coded data to optimize retention/accuracy.

Point-of-Sale Audit

The Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Setting (STARS)14 and prior vape shop surveillance work28 were used to develop the point-of-sale surveillance tool (specific measures below). To assess inter-rater reliability, trained pairs conducted point-of-sale assessments (duration 15–45 minutes).

Age Verification

We assessed signage indicating minimum-age requirements for entering and purchasing.

Health Warnings and Claims

We assessed (1) whether required FDA health warning labels were visible on no, some, or most/all closed devices and e-liquids, respectively; (2) health warnings posted on signage (eg, contraindications, cautions); and (3) messaging related to health claims (eg, safer than other tobacco, safe in general, health benefits, cessation aid).

Product Availability

We assessed (1) devices (closed systems, open systems, herbal/dry chamber vaporizers, wet/dry vaporizers, Juul- and Suorin-specific brands); (2) types of e-liquids (shop’s own brand, other vendors’ brands, e-liquids containing nicotine salt, ranges of nicotine and nicotine salt, e-liquids containing CBD); (3) other CBD or tobacco products; and (4) pipes, glassware, or wrapping papers. Data collectors also assessed e-liquid sampling by identifying signage regarding sampling, inquiring shop personnel if sampling (free or otherwise) was provided, and/or probing to determine conditions under which sampling could occur.

Price

Lowest and highest prices for devices (closed systems, open systems with and without starter kits) and for e-liquids (with and without nicotine salt) were assessed.

Promotions

We assessed price specials on devices or e-liquids (eg, buy one, get one; two for one); happy hour/early bird specials; daily/weekly/monthly specials; membership/loyalty/rewards programs; e-liquid bargain bins; drawings/raffles for discounts/coupons; discounts for military/veterans; and discounts for college students. We also assessed advertising signage, defined as follows: 8.5 × 11 inches or larger, branded with the intent to sell product, and professionally produced and/or amateur/hand written.41 We assessed signage promoting products or price promotions and signage using cartoon imagery (use of comically exaggerated features, attribution of human characteristics to animals, etc.42). We also assessed other ways of promotion, such as chalkboards/whiteboards, lit-up signs, TV/other screens, or functional items (eg, pens, changemats). Promotional products available for consumers to take for free (eg, stickers/decals) or for purchase (shop/product-branded apparel/paraphernalia) were also assessed. Finally, we assessed promotion of shops’ social media page(s) or delivery options.

Vape Shop Setting/Context

Other nearby facilities (eg, smoke/head shops, other vape shops, liquor stores, schools, parks) were assessed by walking/driving around each retailer covering two blocks in each direction using reliable, validated methods.43 We also assessed no-vaping or smoking signs and actual vaping/smoking on premises, as well as vape shop interior settings (ie, lounge seating, tasting bars).

Training and Quality Control

Staff completed a 3.5-day training in Atlanta. Among the 30 randomly selected vape shops in Atlanta, both point-of-sale audit teams (two pairs) and two mystery shoppers (working alone) were each assigned 18 shops; six shops were assessed by two point-of-sale audit teams and two mystery shoppers to examine initial reliability among teams/mystery shoppers. (Note that all data collectors were trained in both data collection protocols but were designated exclusively to point-of-sale or mystery shopper audits throughout data collection.) Staff checked in weekly with the first and second authors (C.B., D.B.) to address data collection issues, ensure data quality, and provide feedback on emergent themes potentially integrated into surveillance tools. Thus, after assessments in Atlanta and Oklahoma, the point-of-sale surveillance tool was revised to include additional items (noted in Tables 1–3).

Table 1.

Smoking/Vaping on Premises, Age Verification, and Health Warning and Claims Across Vape Shops in Six US Metropolitan Areas

| Total | Atlanta | Boston | MSP | OKC | San Diego | Seattle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Kappa | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p* | |

| Age verification | N = 179 | N = 29 | N = 29 | N = 30 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | ||

| Any minimum-age signage | 171 (95.5) | 0.83 | 27 (93.1) | 29 (100.0) | 29 (96.7) | 29 (93.6) | 27 (90.0) | 30 (100.0) | .361 |

| Minimum age to enter signage | 109 (60.9) | 0.68 | 18 (62.1) | 21 (72.4) | 15 (50.0) | 23 (74.2) | 5 (16.7) | 27 (90.0) | <.001 |

| Minimum age to purchase signage | 162 (90.5) | 0.83 | 23 (79.3) | 29 (100.0) | 29 (96.7) | 26 (83.9) | 27 (90.0) | 28 (93.3) | .050 |

| Per mystery shoppera | N = 174 | — | N = 27 | N = 28 | N = 28 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | |

| Age verification upon entrya | 62 (35.6) | — | 5 (18.5) | 15 (53.6) | 11 (39.3) | 2 (6.5) | 8 (26.7) | 21 (70.0) | <.001 |

| Among those without age verification on enteringa | N = 107 | — | N = 21 | N = 13 | N = 17 | N = 27 | N = 22 | N = 7 | |

| Age verification upon attempting purchasea | 25 (23.4) | — | 5 (23.8) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (47.1) | 1 (3.7) | 8 (36.4) | 2 (28.6) | <.001 |

| Health warnings | N = 179 | N = 29 | N = 29 | N = 30 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | ||

| Signage with health warnings | 34 (19.0) | 0.42 | 10 (34.5) | 11 (37.9) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (25.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (16.7) | <.001 |

| Any FDA health warning labels | 153 (85.5) | 0.96 | 27 (93.1) | 27 (93.1) | 22 (73.3) | 23 (74.2) | 30 (100.0) | 24 (80.0) | .004 |

| FDA health warnings visible on closed-system devices | 14 (8.0) | 1.00 | 10 (34.5) | 1 (3.5) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) | <.001 |

| FDA health warnings visible on at least some e-liquids | 151 (84.8) | 0.98 | 27 (93.1) | 27 (93.1) | 22 (73.3) | 22 (73.3) | 30 (100.0) | 23 (76.7) | <.001 |

| Health or cessation aid claims | N = 179 | N = 29 | N = 29 | N = 30 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | ||

| Any signage with health claims or cessation claims | 52 (29.1) | 0.69 | 10 (34.5) | 13 (44.8) | 8 (26.7) | 12 (38.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (30.0) | .003 |

| Signage with health claims | 38 (21.2) | 0.60 | 9 (31.0) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (20.0) | 9 (29.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (26.7) | .043 |

| Signage with aid in cessation claims | 26 (14.5) | 0.66 | 3 (10.3) | 11 (37.9) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | .005 |

Because mystery shopper assessments were conducted first and mystery shoppers did not identify as researchers, the total N for mystery shopper assessments was 196; however, for consistency, we report on only the 174 that coincided with point-of-sale audits. Bold italic words indicate subgroup analyses; italics. Italic words indicate aggregate variables encompassing non-italicized factors listed below. Italic numbers indicate significant p-values. MSP = Minneapolis-St. Paul; OKC = Oklahoma City.

aPer mystery shopper.

*All significance levels refer to omnibus tests.

Table 2.

Products and Measure Reliability Across 179 Vape Shops in Six US Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)

| Total | Atlanta | Boston | MSP | OKC | San Diego | Seattle | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 179 | N = 29 | N = 29 | N = 30 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | |||

| N (%) | Kappa | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Device products | |||||||||

| Closed systems | 116 (64.8) | 0.96 | 24 (82.8) | 28 (96.6) | 8 (26.7) | 16 (51.6) | 15 (50.0) | 25 (83.3) | <.001 |

| Open systemsa | 179 (100.0) | n/a | 29 (100.0) | 29 (100.0 | 30 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) | n/a |

| Juul | 94 (52.5) | 0.97 | 21 (72.4) | 23 (79.3) | 5 (16.7) | 13 (41.9) | 12 (40.0) | 20 (66.7) | <.001 |

| Suorin | 158 (88.3) | 0.95 | 26 (89.7) | 28 (96.6) | 26 (86.7) | 21 (67.7) | 29 (96.7) | 28 (93.3) | .004 |

| Herbal/dry chamber vaporizers | 56 (34.4) | 0.97 | 8 (29.6) | 17 (58.6) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (16.1) | 7 (24.1) | 14 (63.6) | <.001 |

| Combined wet/dry vaporizers | 43 (26.4) | 0.93 | 4 (14.8) | 12 (41.4) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (14.8) | 14 (60.9) | <.001 |

| E-liquid products | |||||||||

| Sells vape shop’s own brand | 122 (68.2) | 0.99 | 21 (72.4) | 8 (27.6) | 24 (80.0) | 31 (100.0) | 17 (13.9) | 21 (70.0) | <.001 |

| Sells other vendor’s brands | 160 (89.4) | 1.00 | 28 (96.6) | 29 (100.0) | 22 (73.3) | 29 (93.6) | 22 (73.3) | 30 (100.0) | <.001 |

| Sells e-liquids with nicotine saltb | 145 (81.0) | 0.96 | 25 (86.2) | 27 (93.1) | 20 (66.7) | 20 (64.5) | 23 (76.7) | 30 (100.0) | .001 |

| Nicotine levels | M (SD) | ICC | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | p |

| Lowest level nicotine (mg) | 0.02 (0.22) | 1.00 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.10 (0.56) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | .383 |

| Highest level nicotine (mg) | 20.03 (8.92) | 1.00 | 23.46 (15.57) | 17.38 (6.87) | 18.83 (6.18) | 23.81 (7.01) | 16.90 (6.98) | 19.70 (5.09) | .004 |

| Lowest level nicotine salt (mg)b | 20.45 (13.55) | 1.00 | n/a | 22.45 (9.35) | 18.60 (16.53) | 10.97 (12.73) | 22.57 (13.20) | 28.31 (8.32) | <.001 |

| Highest level nicotine salt (mg)b | 39.28 (20.46) | 1.00 | n/a | 45.34 (13.49) | 32.27 (23.39) | 30.81 (23.78) | 38.24 (22.53) | 50.55 (5.67) | <.001 |

| N (%) | Kappa | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| Sells e-liquids containing CBD | 76 (42.5) | 1.00 | 22 (75.9) | 19 (65.5) | 7 (23.3) | 19 (61.3) | 8 (10.5) | 1 (3.3) | <.001 |

| Other CBD productsb | 35 (23.3) | 0.92 | n/a | 11 (37.9) | 6 (20.0) | 10 (32.3) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (6.7) | .036 |

| Pipes/glassware/papers | 33 (18.4) | 0.94 | 0 (0.0) | 17 (58.6) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (20.0) | 8 (26.7) | <.001 |

| Access to e-liquids | |||||||||

| E-liquids sampling (in ways below)b | 135 (90.0) | 0.96 | n/a | 23 (79.3) | 29 (96.7) | 26 (83.9) | 29 (96.7) | 28 (93.3) | .092 |

| Use shop’s device and e-liquid without nicotine | 69 (46.0) | 0.95 | n/a | 6 (20.7) | 23 (76.7) | 10 (32.3) | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | <.001 |

| Use shop’s device and e-liquid with nicotine | 24 (16.0) | 1.00 | n/a | 3 (10.3) | 8 (26.7) | 6 (19.4) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (13.3) | .381 |

| Use own device and e-liquid without nicotine | 30 (20.0) | 0.93 | n/a | 2 (6.9) | 3 (10.0) | 5 (16.1) | 14 (46.7) | 6 (20.0) | <.001 |

| Use own device and e-liquid with nicotine | 6 (4.0) | 0.91 | n/a | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (3.3) | .137 |

| Smell | 82 (54.7) | 0.99 | n/a | 16 (55.2) | 15 (50.0) | 21 (67.7) | 13 (43.3) | 17 (56.7) | .405 |

| Taste | 36 (24.0) | 1.00 | n/a | 4 (2.7) | 5 (16.7) | 9 (29.0) | 7 (23.3) | 11 (36.7) | .241 |

| Parameters (eg, membership, cost/trial) | 5 (3.3) | 0.89 | n/a | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Offer free e-liquid samples | 29 (16.3) | 0.98 | 5 (17.2) | 1 (3.5) | 4 (13.8) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (10.0) | 14 (46.7) | <.001 |

| Device prices (in USD) | M (SD) | ICC | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | p |

| Least expensive closed system | 37.12 (15.26) | 0.98 | 35.26 (15.08) | 33.61 (9.65) | 35.24 (20.01) | 31.91 (15.98) | 50.08 (19.19) | 41.04 (13.28) | .010 |

| Most expensive closed system | 48.36 (13.75) | 0.98 | 51.67 (10.94) | 44.72 (12.41) | 46.23 (14.35) | 38.92 (14.15) | 64.72 (13.51) | 48.99 (9.9) | <.001 |

| Least expensive open-system starter kit | 29.46 (12.09) | 1.00 | 29.21 (14.17) | 35.32 (14.73) | 27.59 (9.52) | 22.91 (7.44) | 33.23 (12.45) | 29.21 (9.75) | .001 |

| Most expensive open-system starter kit | 101.98 (43.22) | 0.99 | 104.08 (42.25) | 98.57 (25.81) | 130.99 (60.98) | 62.53 (26.39) | 112.36 (25.26) | 105.11 (35.31) | <.001 |

| Least expensive open-system, not starter kit | 54.38 (18.95) | 1.00 | 46.46 (18.93) | 53.34 (17.14) | 50.83 (16.68) | 63.23 (18.93) | 55.29 (17.64) | 56.88 (20.8) | .016 |

| Most expensive open-system, not starter kit | 130.17 (89.48) | 0.94 | 154.61 (116.93) | 106.18 (34.54) | 129.09 (45.81) | 118.03 (50.57) | 145.02 (170.78) | 130.29 (54.53) | .373 |

| E-liquid prices (in USD) | |||||||||

| Least expensive e-liquid (price/mL) | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.32 | .001 | |

| Most expensive e-liquid (price/mL) | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.37 | .001 | |

MSP = Minneapolis-St. Paul; OKC = Oklahoma City; n/a = not applicable.

aNo kappa computed due to lack of variability.

bNot assessed in Atlanta.

*All significance levels refer to omnibus tests.

Table 3.

Marketing and Promotional Strategies and Inter-rater Reliability Measures Across 179 Vape Shops in Six US MSAs

| Total | Atlanta | Boston | MSP | OKC | San Diego | Seattle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 179 | N = 29 | N = 29 | N = 30 | N = 31 | N = 30 | N = 30 | |||

| N (%) | Kappa | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p* | |

| Any price promotions | 149 (83.2) | 0.69 | 21 (72.4) | 19 (65.5) | 28 (93.3) | 25 (80.7) | 28 (93.3) | 28 (93.3) | .008 |

| Any signage with product/price promotions | 161 (89.9) | 0.62 | 23 (79.3) | 26 (89.7) | 29 (96.7) | 29 (93.6) | 25 (83.3) | 29 (96.7) | .148 |

| Devices | 84 (46.9) | 0.70 | 12 (41.4) | 14 (48.3) | 12 (40.0) | 10 (32.3) | 10 (33.3) | 26 (86.7) | <.001 |

| Device price promos | 36 (20.1) | 0.39 | 2 (6.9) | 9 (31.0) | 7 (23.3) | 5 (16.1) | 4 (13.3) | 9 (30.0) | .131 |

| E-liquids | 151 (84.4) | 0.64 | 21 (72.4) | 24 (82.8) | 27 (90.0) | 27 (87.1) | 23 (76.7) | 29 (96.7) | .101 |

| E-liquid price promos | 82 (45.8) | 0.52 | 10 (34.5) | 15 (51.7) | 12 (40.0) | 13 (41.9) | 13 (43.3) | 19 (63.3) | .279 |

| Signage promoting CBD productsa | 31 (26.1) | 0.86 | n/a | 17 (58.6) | 6 (20.0) | n/a | 6 (20.0) | 2 (6.7) | <.001 |

| Signage with cartoons | 49 (27.4) | 0.46 | 11 (37.9) | 13 (44.8) | 2 (6.7) | 10 (32.3) | 3 (10.0) | 10 (33.3) | .003 |

| Promotional items | |||||||||

| Shop/product apparel or paraphernalia | 104 (58.1) | 0.61 | 14 (48.3) | 21 (72.4) | 22 (73.3) | 18 (58.1) | 13 (43.3) | 16 (53.3) | .093 |

| Shop/product stickers or decals | 111 (62.0) | 0.65 | 12 (41.4) | 13 (44.8) | 24 (80.0) | 23 (74.2) | 13 (43.3) | 26 (86.7) | <.001 |

| Advertising on social media | 47 (26.3) | 0.70 | 5 (17.2) | 14 (48.3) | 6 (20.0) | 11 (35.5) | 4 (13.3) | 7 (23.3) | .022 |

| Delivery options (eg, free delivery) | 5 (2.8) | 0.74 | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

MSP = Minneapolis-St. Paul; OKC = Oklahoma City; n/a = not applicable.

aNot assessed in Atlanta or Oklahoma City.

*All significance levels refer to omnibus tests.

Data Analysis

Using SAS 9.4, we conducted descriptive analyses and then bivariate analyses to identify differences among the MSAs using chi-square tests for categorical outcomes and ANOVA for continuous outcomes. When cell sizes were small (ie, ≤5), Fisher’s exact test was used. We conducted analyses on the dimensions assessed by the point-of-sale auditors to determine inter-rater reliability, using kappas for categorical variables estimated in PROC FREQ and ICCs for continuous variables in PROC MIXED.

Results

Age Verification

Overall, 95.5% had minimum-age signage, either to enter (60.9%) or to purchase (90.5%; Table 1). Of the 174 mystery shopper assessments, 35.6% resulted in age verification upon entry; of 107 subsequent purchase attempts, only 23.4% resulted in age verification at purchase. The poorest age verification practices were documented in Oklahoma City and Atlanta.

Health Warnings and Claims

Signage with health warnings was documented in 19.0% of shops (Table 1). While 85.5% of shops had some evidence of implementing the impending FDA health warnings on products, with 84.8% having some FDA health warnings on e-liquids and 8.0% on closed-system devices.

However, 29.1% had at least one sign indicating health claims (21.2%) and/or claims that vaping aids in cessation (14.5%), with San Diego having no shops with such claims and Boston having 44.8% of shops with such claims (Table 1). When personnel were asked by mystery shoppers if vaping was safer than smoking, 100.0% affirmed either “Yes” or “I’m not supposed to say that, but yes” (ie, they legally could not make medical claims but believed so or their personal experience suggested so). When mystery shoppers asked whether he/she could quit or his/her friend could quit smoking by vaping, 100.0% (n = 86/86) and 98.8% (n = 85/86) said “yes,” respectively.

Product Availability

All vape shops sold open-system devices, with 64.8% also selling closed-system (Table 2). Additionally, 88.3% sold Suorin, and 52.5% sold Juul. Additionally, 34.4% sold herbal/dry chamber vaporizers, and 26.4% sold combined wet/dry vaporizers.

Two-thirds (68.2%) of shops sold their own brand of e-liquids, and overall 84.4% sold other vendors’ brands. In addition, 81.0% sold e-liquids containing nicotine salt, and 42.5% sold e-liquids containing CBD. Other CBD products were sold in 23.3% of shops. About a fifth (18.4%) sold pipes, glassware, or wrapping papers. Nicotine levels (without salt) ranged 0–50 mg, and nicotine salt levels ranged 0–75 mg.

Significant differences in product availability across MSAs were documented. For example, shops in Minneapolis-St. Paul were least likely to sell closed-system devices (26.7% vs. ≥50% in the other MSAs). Shops in Seattle, where retail marijuana is legal, were most likely to sell herbal/dry chamber vaporizers or combined wet/dry vaporizers (63.6% and 60.9% vs. ≤58.6% and ≤41.4%, respectively, in other MSAs). Shops in Oklahoma City were most likely to sell their own brand of e-liquids (100.0% vs. ≤80.0% in other MSAs). Shops selling e-liquids containing CBD were most commonly found in Atlanta (75.9%), Boston (65.5%), and Oklahoma City (61.3%). Other CBD products were also most prominent in Boston (37.9%) and Oklahoma City (32.3%). (Note that this item was added to the surveillance tool after Atlanta data collection, as it emerged as a theme that had not been systematically assessed.)

E-liquid Sampling

E-liquid sampling was available at 90.0% of shops (Table 2), with 16.3% offering free samples. Samples were provided in a range of ways, including using the shop’s devices or the consumers’ devices either with or without nicotine, as well as by smelling or tasting e-liquids. Parameters regarding sampling were also noted, such as samples for a quarter or membership programs that, with a small annual fee, would cover unlimited samples.

Pricing

Table 2 provides average low and high prices for products across MSAs, indicating significant differences across MSAs. Price ranges were as follows: closed-system devices, $7.49–$90; open-system starter kits, $9.99–$300; open-system devices (no starter kit), $12.95–$900; and e-liquids, $0.11–$4.65 per mL.

Promotional Strategies

Overall, 83.2% of shops offered price promotions of some kind, with 55.9% having price specials on e-liquids (eg, buy one, get one); 41.3% membership, loyalty, or rewards programs; 26.3% price specials on devices; 25.7% e-liquid bargain bins; 24.0% daily, weekly, or monthly specials on e-liquids; 13.4% happy hour or early bird specials on e-liquids; and 13.4% discounts for military/veterans. Despite significant differences across the MSAs, price promotions were found in >65% of shops in each MSA.

In total, 89.9% of shops displayed promotion signage, with 27.4% having signage that used cartoon imagery and 26.1% having signage promoting CBD products (note: CBD item added to the surveillance tool after assessments in Atlanta and Oklahoma City). Advertising and promotions were also conveyed through chalkboards/whiteboards (56.4%), lit-up signs (26.8%), TV/other screens (22.4%), or functional items (eg, pens, 62.6%). A range of promotional items was also available for customers to purchase or take away, including shop/product-branded apparel/paraphernalia (58.1%) and/or stickers/decals (62.0%). Over a fourth (26.3%) promoted their shop’s social media page(s), and 2.8% indicated delivery options.

Vape Shop Setting and Context

With regard to location, 35.3% of vape shops were within two blocks of liquor stores, 33.6% schools, 21.0% head/smoke shops, 16.8% parks, 9.2% other vape shops, 5.0% playgrounds, 4.2% college campuses, and 1.7% marijuana retailers. No-vaping or no-smoking signs were observed in 10.1% and 21.8% of shops, respectively; 73.2% had vaping occurring and 1.7% had smoking on premises during assessment. Regarding interior context, 88.8% had customer lounge seating, and 65.2% had counter/tasting bar seating.

Inter-rater Reliability

Kappas ranged 1.00 (for FDA health warning labels on closed-system devices, selling other vendors’ e-liquid brands, e-liquids that contain CBD, use of shop device to vape e-liquid with nicotine, taste test; Tables 1 and 2) to 0.39 (for device price promotion signage; Table 3).44 Inter-rater reliability for other product availability measures were good to excellent (kappas ranging 0.79–0.99; Table 2). Items with kappas below 0.60 (see Tables 1 and 3) may have resulted due to interpretation, for example, with regard to functional items (kappa = 0.49) or signage with health warnings (kappa = 0.42), health claims (kappa = 0.60), cessation claims (kappa = 0.66), cartoons (kappa = 0.46), or product/price promotions (kappa = 0.62). Regarding the latter, there may have been inconsistencies where device prices were posted on signage but may not have been special promotional prices; in these cases, auditors may have coded such signs as either product or price promotion signage.

Discussion

The present study used rigorous retail surveillance methods and provided important empirical findings regarding vape shop retail in the midst of global increases in vaping and vape shops,1 controversy regarding population risks and benefits of vaping,2–4 implementation of existing FDA regulations, and further regulation to address youth vaping.22,23 Findings indicated concerns in relation to age verification, health claims, promotional strategies, and CBD product availability.

Overall, 95.5% of shops had some minimum-age signage, similar to rates shown in other research.14 However, only a third verified age upon entry, and in shops where age was not verified at entry, only a quarter of the purchase attempts resulted in age verification. Moreover, one in three shops were located near schools, historically an issue with tobacco retailers24 and marijuana dispensaries.45 Similar to legislation regarding alcohol and traditional tobacco retailers, state and/or local retail licensing laws may prohibit vape shop retail proximity to child-friendly areas (eg, schools, playgrounds).10 Also noteworthy, over 25% of shops displayed signage with cartoon imagery, similar to prior findings from e-cigarette industry Instagram posts.42 Although few shops indicated delivery options, a quarter indicated advertising on social media (with implications for youth exposure to vaping)8 and links to online purchasing that may facilitate sales to minors.46 These findings underscore the need for regulatory efforts to curb youth vaping.22,23

During data collection (May–July 2018), the majority of shops displayed some FDA health warning labels, mostly on e-liquids. This was promising, as by August 2018, all devices and e-liquids were required to carry a warning label about nicotine. However, nearly a third of shops had signage indicating health or cessation aid claims, similar to the prevalence found in other research.14 Moreover, when mystery shoppers asked shop personnel about vaping, personnel universally endorsed vaping safety and utility in supporting cessation; prior research has similarly shown that vape shop personnel endorse these beliefs and frequently make claims regarding vaping safety and/or use for cessation.14,37 Although evidence has increasingly supported a role of e-cigarettes in cessation,2–4 it is illegal to market vaping devices as cessation aids without FDA approval as modified-risk tobacco products. However, vape shop personnel frequently couched their responses regarding the utility of vaping for cessation in their personal experiences. Vaping on premises was also prevalent, which may also implicitly promote product safety.

Vape shops offered various devices, nicotine levels, prices, brands, and flavors, likely to appeal to consumers who prioritize different product characteristics.13,47 This is important, as more advanced devices and the broad range of nicotine levels may support cessation efforts.4,12 Promotions were also pervasive, with >80% having some type of price promotion. Almost all offered some way to sample e-liquids, similarly noted in other research.14 Although few provided free samples, other strategies, such as membership/loyalty programs that included sampling as part of annual fees, were used to side-step “free” sample bans. Additionally, the majority of shops had customer lounges or bars, which facilitate sampling and socializing as well as exposure to secondhand aerosol.13,25,48 The majority also sold or gave away shop/product-branded apparel, paraphernalia, or stickers/decals. These findings collectively suggest that vape shop marketing aims to build shop brand loyalty by having diverse products available and engaging consumers.

E-liquids and other products containing CBD were prominent, particularly in Atlanta, Boston, and Oklahoma City. Laws regarding CBD across states vary and are often vague.49 States with legalized recreational and medical marijuana (ie, California, Colorado, Washington) or medical marijuana only (ie, Massachusetts [at time of assessment], Minnesota) have regulatory entities overseeing marijuana/cannabis, which may deter vape shops from selling such products. However, states such as Georgia and Oklahoma (at time of assessment) allow certain levels of CBD,49 but have limited regulatory oversight of such products.

Areas for Future Research

The surveillance methods used in this study allow further examination of vape shop retail over time and across contexts, particularly critical given different regulatory environments across states and countries and pending FDA regulation implementation. Research must also bridge across brick-and-mortar retail and online retail to ascertain underage access and advertising using safety and cessation claims or cartoon imagery to ultimately inform regulatory efforts to minimize youth access and exposure more broadly. Additionally, how different messaging strategies regarding health risks versus claims are perceived should be further examined, as research has indicated that consumers may perceive reduced health risk even if language does not explicitly state reduced risk.50 In addition, further assessment is needed regarding CBD product characteristics within vape shops to inform state regulation and enforcement.

Limitations

Findings have limited generalizability to vape shops in the MSAs, across the United States, and across the world. The assessment tools also required adaptation across contexts to account for themes that emerged, thus underscoring that (1) findings across settings should be considered within the relevant policy context and (2) surveillance tools must adapt within the current context, particularly relevant as the tobacco/vaping product market and policy contexts change over time and across jurisdictions. Additionally, despite rigorous data collection training and quality control, data may have been affected by differences in how research staff approached assessment or how vape shop personnel interacted with research staff. Relatedly, inter-rater reliability on some assessments, specifically signage regarding health warnings/claims, cartoon imagery, and product/price promotions, indicates the needs for improved training and to acknowledge that these messages may not be explicit. Additionally, age verification gaps may have resulted from vape shop personnel perceiving mystery shoppers to be ≥27 years old. Finally, the quickly evolving vape products and discourse regarding their impact on youth will require retail, and thus surveillance efforts, to adapt accordingly.

Conclusion

Current findings indicated some implementation of FDA health warnings, some compliance with free sampling prohibition, and high rates of compliance with minimum-age signage alongside concerns related to actual age verification, health claims, promotional strategies, and CBD product offerings. FDA and state/local regulation must step up enforcement efforts and address attempts to circumvent existing laws/regulations. Moreover, this study provides baseline data for comparison with future surveillance efforts documenting the impact of full implementation of FDA regulations on vape shop marketing at point-of-sale.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Funding

This publication was supported the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg). Dr. Berg is also supported by other NCI funding (R01 CA179422-01; PI: Berg; P30 CA138292; PI: Curran) and the US Fogarty International Center/NCI (1R01TW010664-01; MPIs: Berg, Kegler).

Dr. Pulvers is supported by funding from the NIH (SC3GM122628; PI: Pulvers; R01 CA190347; MPIs: Strong and Pierce), TRDRP (27IP-0041; PI: Pulvers; 28IP-0022S; PI: Oren), and the USDHHS (3GM1226290FK0105-01-00; PI: Fernando Sañudo).

Dr. Wagener is supported by funding from the NIH and US FDA (R01CA204891, PI: Wagener; U01DA045537, PI: Wagener; R21DA046333, MPI: Wagener and Villanti).

Ethical Approvals

Institutional Review Board approvals were not required for this manuscript, as no human subjects were involved in this manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De Leon E, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(2):116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):1926–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, Stead L, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD010216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. New Report One of the Most Comprehensive Studies on Health Effects of E-Cigarettes; Finds That Using E-Cigarettes May Lead Youth to Start Smoking, Adults to Stop Smoking. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; 2018. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2018/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Centers for Disease Control; https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Published 2019. Accessed December 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Products: Vaporizers, E-Cigarettes, and other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) US Food and Drug Administration; https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/productsingredientscomponents/ucm456610.htm. Published 2019. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee JGL, Orlan EN, Sewell KB, Ribisl KM. A new form of nicotine retailers: a systematic review of the sales and marketing practices of vape shops. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e70–e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Public Health Law Center. U.S. E-Cigarette Regulations—50 State Review (2019) Public Health Law Center; https://publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review. Published2019. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dai H, Hao J, Catley D. Vape shop density and socio-demographic disparities: a US census tract analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(11):1338–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen C, Zhuang YL, Zhu SH. E-cigarette design preference and smoking cessation: a U.S. population study. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(3):356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sussman S, Garcia R, Cruz TB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Pentz MA, Unger JB. Consumers’ perceptions of vape shops in Southern California: an analysis of online Yelp reviews. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kong AY, Eaddy JL, Morrison SL, Asbury D, Lindell KM, Ribisl KM. Using the vape shop standardized tobacco assessment for retail settings (V-STARS) to assess product availability, price promotions, and messaging in New Hampshire vape shop retailers. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheney M, Gowin M, Wann TF. Marketing practices of vapor store owners. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):e16–e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burton S, Clark L, Jackson K. The association between seeing retail displays of tobacco and tobacco smoking and purchase: findings from a diary-style survey. Addiction. 2012;107(1):169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg CJ Preferred flavors and reasons for e-cigarette use and discontinued use among never, current, and former smokers. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(2):225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Getachew B, Payne J, Vu M, et al Perceptions of alternative tobacco products, anti-tobacco media, and tobacco regulation among young adult tobacco users: a qualitative study. Am J Health Behav. 2018;42(4):118–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berg CJ, Escoffery C, Bundy L, Haardoerfer R, Zheng P, Kegler MC. Cigarette users interest in using or switching to electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or smokeless tobacco for harm reduction, cessation, or novelty. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014. 17(2):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Food and Drug Administration. FDA, FTC Take Action Against Companies Misleading Kids With E-Liquids That Resemble Children’s Juice Boxes, Candies and Cookies.Food and Drug Administration; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-ftc-take-action-against-companies-misleading-kids-e-liquids-resemble-childrens-juice-boxes. Published 2018. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vazquez M, Klein B. Trump administration moves to ban flavored e-cigarettes. CNN News. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berg CJ Vape shop location and marketing in the context of the Food and Drug Administration regulation. Public Health. 2018;165:142–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sussman S, Allem JP, Garcia J, et al. Who walks into vape shops in Southern California? a naturalistic observation of customers. Tob Induc Dis. 2016;14(18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grana RA, Ling PM. “Smoking revolution”: a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smoke-free Alternative Trade Association. U.S. Vape Shops Average $26K in Monthly Sales, According to Industry Index. PR Newswire; http://sfata.org/u-s-vape-shops-average-26k-in-monthly-sales-according-to-industry-index/. Published 2015. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barker DC, Huang J, Nayak P, et al. Marketing practices in vape shops in U.S. cities. 2016 Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; 2016; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, De[onovan DM, Windle M. Differences in tobacco product use among past month adult marijuana users and nonusers: findings from the 2003–2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(3):281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003–2012. Addict Behav. 2015;49:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reuters JM The US Vaporizer Market Is Booming Business Insider Web site; http://www.businessinsider.com/r-in-rise-of-us-vape-shops-owners-eye-new-marijuana-market-2015–7. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Favrat B. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9988–10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McDonald EA, Popova L, Ling PM. Traversing the triangulum: the intersection of tobacco, legalised marijuana and electronic vaporisers in Denver, Colorado. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 1):i96–i102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gosselt JF, Van Hoof JJ, De Jong MD. Why should I comply? Sellers’ accounts for (non)compliance with legal age limits for alcohol sales. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krevor BS, Ponicki WR, Grube JW, DeJong W. The effect of mystery shopper reports on age verification for tobacco purchases. J Health Commun. 2011;16(8):820–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JG, Henriksen L, Myers AE, Dauphinee AL, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of store audit methods for assessing tobacco marketing and products at the point of sale. Tob Control. 2014;23(2):98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wagoner KG, Berman M, Rose SW, et al. Health claims made in vape shops: an observational study and content analysis. Tob Control. 2019;28:e119–e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim AE, Loomis B, Rhodes B, Eggers ME, Liedtke C, Porter L. Identifying e-cigarette vape stores: description of an online search methodology. Tob Control. 2016;25(e1):e19–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee JG, D’Angelo H, Kuteh JD, Martin RJ. Identification of vape shops in two north Carolina counties: an approach for states without retailer licensing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li W, Gouveia T, Sbarra C, et al. Has Boston’s 2011 cigar packaging and pricing regulation reduced availability of single-flavoured cigars popular with youth? Tob Control. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henriksen L, Ribisl K, Rogers T, et al. Standardized tobacco assessment for retail settings (STARS): dissemination and implementation research. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 1);i67–i74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Allem JP, Cruz TB, Unger JB, Toruno R, Herrera J, Kirkpatrick MG. Return of cartoon to market e-cigarette-related products. Tob Control. 2018;28:555–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol. Methodol. 1999;29:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 44. McHugh ML Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berg CJ, Henriksen LA, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Schauer G, Freisthler B. Point-of-sale marketing and context of marijuana retailers: assessing reliability and generalizability of the Marijuana Retail Surveillance Tool. Prev Med Reports. 2018;11(2018):37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williams RS, Derrick J, Ribisl KM. Electronic cigarette sales to minors via the internet. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):e1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sussman S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Garcia R, et al. Commentary: forces that drive the vape shop industry and implications for the health professions. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):379–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. ProCon. 17 States With Laws Specifically About Legal Cannabidiol (CBD) ProCon; https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=006473. Published 2019. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Popova L, Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Light and mild redux: heated tobacco products’ reduced exposure claims are likely to be misunderstood as reduced risk claims. Tob Control. 2018;27(Suppl 1):S87–S95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.