Abstract

Purpose of review:

Although gout’s cardinal feature is inflammatory arthritis, it is closely associated with insulin resistance and considered a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. As such, both gout and hyperuricemia are often associated with major cardiometabolic and renal comorbidities that drive the persistently elevated premature mortality rates among gout patients. To that end, conventional low-purine (i.e., low-protein) dietary advice given to many patients with gout warrant reconsideration.

Recent findings:

Recent research suggests that several healthy diets, such as the Mediterranean or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diets, in combination with weight loss for those who are overweight or obese, can drastically improve cardiometabolic risk factors and outcomes. By treating gout as a part of the metabolic syndrome and shifting our dietary recommendations to these healthy dietary patterns, the beneficial effects on gout endpoints should naturally follow for the majority of typical gout cases, mediated through changes in insulin resistance.

Summary:

Dietary recommendations for the management of hyperuricemia and gout should be approached holistically, taking into consideration its associated cardiometabolic comorbidities. Several healthy dietary patterns, many with similar themes, can be tailored to suit comorbidity profiles and personal preferences.

Keywords: gout, hyperuricemia, metabolic syndrome, diet, nutrition

Introduction

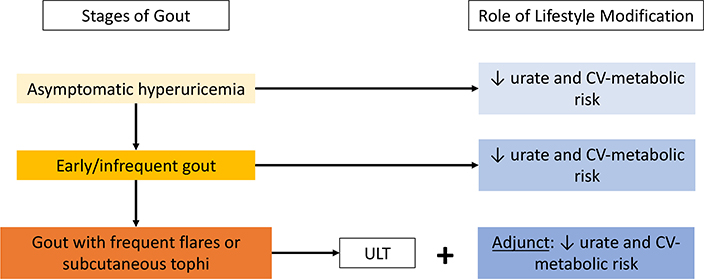

Although gout’s cardinal feature is inflammatory arthritis, its primary underlying cause, hyperuricemia, is considered a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome mediated by insulin resistance.1,2 Thus, hyperuricemia and gout are both associated with adverse consequences of the metabolic syndrome, namely cardiometabolic and renal disease.3–5 To that end, the conventional low-purine (i.e., low-protein) dietary approach focusing on prevention of purine-loading can worsen its cardiometabolic comorbidities by leading to compensatory higher consumption of carbohydrates (including fructose) and fats (including trans or saturated fat). Moreover, the long-term effectiveness of a low-purine diet to lower urate levels remains unclear with its limited palatability and sustainability.1,6 In contrast, there are several preeminent healthy diets that can simultaneously reduce serum urate and the risk of gout and overall cardiometabolic risk by lowering adiposity and insulin resistance. These dietary interventions can be applicable to patients at all stages of gout (Figure 1) and should form a cornerstone of lifestyle counseling for such patients. This article reviews the relevant scientific rationale and available data to provide evidence-based dietary considerations for the prevention and management of hyperuricemia and gout, including the role of diet on gout flares, together with its cardiometabolic comorbidities holistically.

Figure 1.

Stages of Gout and Role of Lifestyle Interventions

CV = cardiovascular; ULT = urate-lowering therapy

The Metabolic Syndrome and Comorbidities of Hyperuricemia and Gout

Insulin resistance is a key feature of the metabolic syndrome, and because insulin resistance can reduce the renal excretion of urate,6–9 hyperuricemia and gout closely coexist with metabolic syndrome.9,10 In the US general population, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome has exceeded >71% among gout patients aged 40 years and older,10 compared with an overall prevalence of 22% among all US adults in the same time period.11 Similarly, the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome tends to rise progressively with increasing serum urate levels, reaching as high as nearly 90% among women with serum urate level >10mg/dL.12 It is well-recognized that patients with gout shoulder a high burden of related comorbidities, including hypertension (74%), chronic kidney disease stage ≥2 (71%), obesity (53%), diabetes (26%), myocardial infarction (14%), and heart failure (11%),3 which are 2 to 3 times more prevalent in those with gout compared to those without.3

In addition to these cross-sectional associations, patients with gout are at an increased risk of future cardiometabolic complications. Gout is associated with a 41% increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes,13 33% increased risk of peripheral arterial disease,14 and 60% increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) among men.15 Consequently, individuals with gout are also at increased risk of myocardial infarction16 and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality.17,18 Thus, any dietary recommendation to address hyperuricemia and gout should simultaneously provide cardiometabolic benefits to reduce this excess morbidity and mortality.

Failure to do so effectively in current practice appears to be reflected in a general population-based cohort study that showed that the level of premature mortality among gout patients remained unimproved over the past two decades (Figure 2a),19 unlike rheumatoid arthritis,20 where mortality improved substantially during the same period (Figure 2b). Furthermore, two recent analyses on the global burden of disease have reported increases in age-adjusted prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years of gout every year from 1990 to 2017 and have identified intensive dietary management as a possible strategy to reverse this trend.21,22

Figure 2:

Persistent Premature Mortality Among Patients with Gout Remains Higher than Premature Mortality in Rheumatoid Arthritis in Recent Decades

Panel (a) compares the cumulative incidence of death from 1999 to 2006 (red lines) to that from 2007 to 2014 (blue lines) among patients with gout (solid lines) and without gout (dotted lines), with the difference between the solid and dotted lines remaining unchanged during the two time periods, indicating persistent premature mortality. Conversely, panel (b) compares the cumulative incidence of death from 1999 to 2006 (red lines) to that from 2007 to 2014 (blue lines) among patients with RA (solid lines) and without RA (dotted lines). The difference in mortality between the two blue lines is substantially smaller than that between the two red lines, indicating an improvement in the mortality gap among patients with RA in the latter time period.

Adapted from: Fisher et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2017 & Zhang et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2017.

RA = rheumatoid arthritis

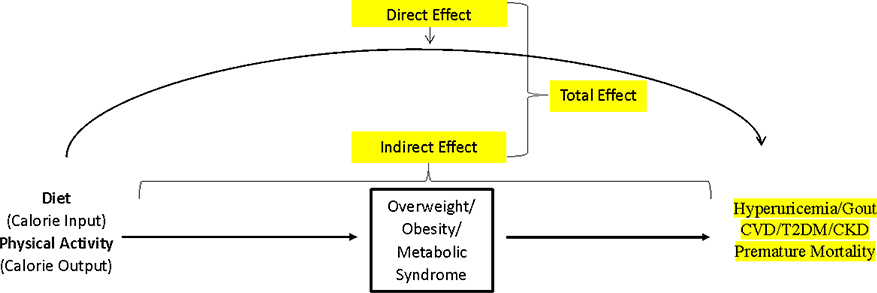

Causal Pathways for Obesity, Hyperuricemia, and Gout

The rising prevalence of gout23 closely following the obesity epidemic in the United States and other Westernized nations can be explained by changes in diet (including larger portion sizes24 and unhealthy dietary composition) and sedentary lifestyle.25–30 While diet quality (i.e., isocaloric composition pattern without impacting body mass index [BMI], or direct effect in Figure 3) has been the main focus in gout care (e.g. low-purine diet), it is important to recognize the impact of diet quantity (caloric intake) and physical activity (caloric output) on the risk of obesity as well as the subsequent risk of cardiometabolic endpoints, including hyperuricemia and gout (indirect effect mediated by obesity, Figure 3).6,31 To this end, a recent analysis of the US general population found BMI was the most important modifiable risk factor for hyperuricemia, with a population attributable risk (i.e., the proportion of hyperuricemia cases attributable to overweight or obesity) of 44%.28

Figure 3:

Causal Pathway Linking Lifestyle Factors with Gout and CV-Metabolic Disease

CVD = cardiovascular disease; T2DM = Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CKD = chronic kidney disease

Shared Risk Factors and Healthy Eating Pyramid

A series of prospective investigations and ancillary studies have investigated the risk of gout associated with relevant lifestyle factors, many of which can be overlaid on a Healthy Eating Pyramid that is designed to prevent major conditions such as CVD and type 2 diabetes (Figure 4).7,8,32 As such, nutritional advice for both cardiometabolic disease and gout centers around weight control and adherence to a general dietary pattern that emphasizes whole grains, healthy unsaturated oils, vegetables and fruits, nuts and legumes, and healthy protein such as poultry, fish, eggs, and low-fat dairy, while limiting the consumption of red meat, refined carbohydrates, and saturated fats. This framework is the repeated theme of healthy diets recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)33 and Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020,34 discussed in detail under Cardiometabolic Diets below.

Figure 4:

Evidence-Based Healthy Eating Pyramid for Gout

*Fish is the only exception where recommendations for gout (short-term) and cardiometabolic health may be contradictory. In the long-term, patients with gout would still benefit from moderate fish consumption if their gout/hyperuricemia is controlled by other measures.

Limitations of Low-Purine Diet

The current conventional lifestyle approach for gout focuses on limitation of protein to reduce purine-loading.1 When the intake of one macronutrient is reduced (e.g., protein), this must be accompanied by a compensatory increase in one or both of the remaining macronutrients (e.g., carbohydrates and fats). Given the prevalence of Western-style diets and deterioration of healthy eating habits,35 there is the risk of protein-restriction leading to increased consumption of foods that are rich in refined carbohydrates (including fructose) and saturated or trans fats. These changes could further exacerbate insulin resistance, leading to higher plasma levels of glucose and lipids, thereby contributing to the development and worsening of metabolic syndrome and its complications in patients with gout.1,6 Furthermore, the long-term therapeutic value of a purine-restricted diet has been questioned due to limited palatability, sustainability, and anti-gout efficacy.1,6

Healthy Cardiometabolic Diets

In contrast, approaches that focus on comprehensive healthy dietary patterns to reduce insulin resistance may be preferable to patients with gout and hyperuricemia to simultaneously address both gout and cardiometabolic risk factors. Based on interventional and prospective cohort studies, several dietary patterns have emerged as preeminent approaches for cardiometabolic health, including the Mediterranean (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-weight/diet-reviews/mediterranean-diet/) and DASH (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-weight/diet-reviews/dash-diet/) diets. These diets incorporate many aspects of the aforementioned Healthy Eating Pyramid and are endorsed by both the AHA/ACC33 and Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020 (https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/).36 Below we discuss in detail the benefits of the Mediterranean and DASH diets among patients with gout. We also summarize several studies which have evaluated the benefits of weight loss through dietary interventions on the effect of gout and cardiometabolic endpoints, which supports adiposity and insulin resistance as being key targets for lifestyle intervention.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet consists of a high intake of monounsaturated fat (primarily from olive oil), plant proteins, whole grains, and fish, accompanied by moderate intake of alcohol and low consumption of red meat, refined grains, and sweets,37 resembling the Healthy Eating Pyramid (Figure 4). The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce the risk of CVD events and CV mortality,38–45 including a 73% lower rate of coronary events and a 70% lower rate of total mortality, compared to a usual post-infarct “prudent” diet in secondary prevention.45 Furthermore, two variations of the Mediterranean diet (one supplemented with olive oil, the other with nuts) were both associated with a >50% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes compared to a control diet;46 findings to this effect have also been replicated in observational cohort studies including the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study.47 In randomized dietary weight loss trials, adherence rates to the Mediterranean diet have been high,38 reaching 85%48 in one, suggesting that such a dietary strategy may be more sustainable than the conventional low-purine diet currently recommended for patients with gout.

Several studies have investigated the beneficial serum urate and gout effects of the Mediterranean diet. For instance, an ancillary analysis of the PREDIMED trial showed that participants in the highest quintile of adherence to the Mediterranean diet had 23% lower odds of having hyperuricemia compared to those in the lowest quintile.49 Furthermore, in a secondary analysis of one of the aforementioned dietary weight loss trials,48 the Mediterranean diet with calorie restriction resulted in a mean reduction in serum urate from baseline of 0.8 mg/dL for all participants and 2.1 mg/dL among those with baseline hyperuricemia (serum urate ≥ 7mg/dL).31

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet

The DASH diet, which emphasizes whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products, with a high intake of plant protein from legumes and nuts in lieu of animal protein sources, was initially developed and studied for the management of hypertension.51–53 The original DASH and DASH-Sodium (DASH with reduced sodium intake) diets have been shown to significantly lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure as well as total and LDL cholesterol.52,53 The OmniHeart trial, which compared a traditional DASH diet with a modified DASH diet with partial substitution of carbohydrates for either healthy sources of protein or monounsaturated fats, showed that in addition to the blood pressure benefits seen with all three diets, the protein-rich and unsaturated fat-rich diets resulted in a significantly greater increase in HDL and decrease in triglycerides. The protein-rich diet also showed a significantly greater decrease in LDL relative to the traditional DASH diet.54 A recent ancillary analysis of this study looking at serum urate endpoints reported that the protein-rich diet reduced serum urate from baseline to the end of the 6-week feeding period more than the carbohydrate-rich or unsaturated fat-rich diets (mean change of −0.12 mg/dL [95% CI, −0.23 to −0.02] for the protein-rich diet, compared to 0 mg/dL for both carbohydrate-rich and unsaturated fat-rich diets). However, all three diets did significantly reduce serum urate among those with baseline hyperuricemia (serum urate ≥6 mg/dL), (all p ≤ 0.003) with no between-group differences. 55 These results are consistent with the notion that a protein-restricted diet may not necessarily be the best option for patients with gout.

Furthermore, several interventional and observational cohorts have reported on the benefits of the DASH diet in reducing the risk of CVD,43,56,57 type 2 diabetes,47,58 and mortality.44,59–61 For example, in the Nurses’ Health Study, those with the highest quintile DASH scores had a 24% lower risk of incident CHD and 29% lower risk of CHD mortality compared to those with the lowest quintile DASH scores.57 Based on this evidence, the original DASH diets, as well as the modifications studied in the OmniHeart trial, have also been endorsed by both the ACC/AHA33 and Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–202034 as another healthy dietary option. Additionally, this suggests that within the framework of the Healthy Eating Pyramid, dietary modifications based on comorbidities and personal preferences are possible without diminishing the beneficial effects of these diets.

As hypertension is present in 74% of patients with gout (and in 50% of people with hyperuricemia),3 it can be argued that the DASH diet would already be indicated for the majority of gout patients to manage their hypertension. Nevertheless, an ancillary analysis of the DASH-Sodium trial showed that the DASH diet resulted in a reduction in serum urate of 0.35mg/dL compared to controls; in a subgroup analysis, the reduction in serum urate was more pronounced among those with baseline hyperuricemia, with a reduction of 0.76 mg/dL and 1.29 mg/dL among those with serum urate 6–7 mg/dL and ≥7 mg/dL, respectively.62 Similarly, an ancillary analysis of a study that involved the partial replacement of a typical diet with the DASH diet suggested a trend towards greater serum urate reduction among African American participants with baseline hyperuricemia.63 In a large population-based cohort of Chinese adults,64 the highest quartile DASH diet score was associated with 30% lower odds of hyperuricemia cross-sectionally. Importantly, this association was significantly greater among physically inactive adults (odds ratio 0.56, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.63) than those with moderate or high levels of physical activity (odds ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.95; p for interaction=0.008).64 Additionally, an analysis of the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study revealed that men with the highest quintile DASH scores had a 32% lower risk of incident gout compared to those with the lowest quintile DASH scores.65 The same analysis among women in the Nurses’ Health Study revealed a similar risk reduction for incident gout with the DASH diet.50

In many ways, a DASH diet shares a number of similarities with a vegan or vegetarian diet, which too have been associated with weight loss and improved cardiometabolic health.66,67 Accordingly, evidence from two non-randomized longitudinal cohort studies suggests that vegetarian diets may also decrease the risk of incident gout,68 with fully-adjusted odds ratios of 0.40 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.97) and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.88), for vegetarians compared to non-vegetarians. However, a recent analysis comparing DASH, fruit and vegetable, and control diets revealed that, among those with baseline hyperuricemia, the DASH diet lowered serum urate levels more robustly than the control diet, while the serum urate-lowering effect of the fruit and vegetable diet was of only borderline significance.69 These results suggest that while increasing fruit and vegetable consumption is a key feature of the DASH diet, there are additional benefits to be gleaned from the dietary pattern as a whole, as opposed to emphasizing a few healthy food groups.

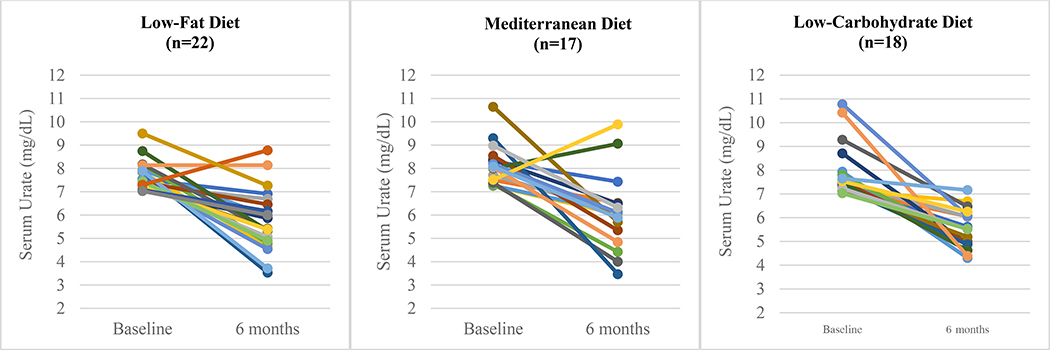

Effects of Weight Loss Diets

Beyond the benefits of isocaloric diets intended to maintain stable weight, reducing insulin resistance through weight loss in overweight and obese individuals could improve both gout and associated cardiometabolic risk. For example, in an ancillary analysis of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT),48 three diets (low-fat, restricted-calorie; Mediterranean, restricted-calorie; low-carbohydrate, non-restricted-calorie, modeled after the Atkins diet) all resulted in a mean reduction in serum urate from baseline of 0.8 mg/dL over 6 months. The effects were more pronounced among those with baseline hyperuricemia (serum urate ≥ 7 mg/dL), with a serum urate reduction from baseline ranging from 1.9 mg/dL with the low-fat diet to 2.4 mg/dL with the low-carb diet (Figure 5).31 Over 6 months, all three diets resulted in significant weight loss ranging from 5.0 kg with the low-fat diet to 7.0 kg with the low-carb diet, as well as improvements in other cardiometabolic parameters such as lipids and fasting insulin levels.31 In this secondary analysis, the serum urate reduction attenuated at 24 months (ranging from 1.1 to 1.4 mg/dL reduction among those with baseline hyperuricemia), likely mediated by regaining some of the weight that had been lost during the initial 6 months of the study.31

Figure 5:

Serum Urate Change at 6 Months Among Participants with Baseline Hyperuricemia in Ancillary Analysis of Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial

Adapted from: Yokose et al. Diabetes Care 2020.

Furthermore, a pilot study (n=13 gout patients) that aimed to lower insulin resistance over 16 weeks by reducing calorie intake with a diet high in protein (i.e., the opposite of the conventional low-purine diet) and low in carbohydrates and saturated fat found that mean serum urate levels decreased from 9.6 to 7.9 mg/dL and the frequency of monthly gout flares decreased from 2.1 to 0.6.6 Additional cardiometabolic benefits included significant improvements in total cholesterol, total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio, and triglyceride levels.6 Together, these studies support that dietary approaches to reduce insulin resistance through weight loss in overweight and obese individuals could improve both gout outcomes and associated cardiometabolic risk. Further, these studies suggest that the conventional low-purine dietary advice given to many patients with gout warrants reconsideration.

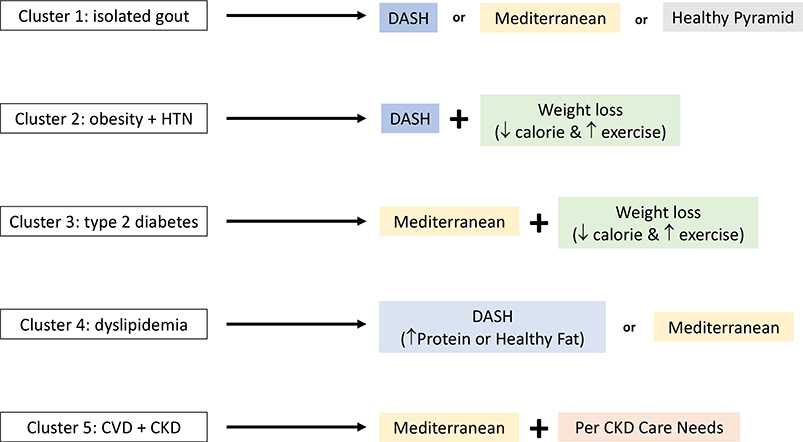

Personalized Lifestyle Recommendations

Given the multiple healthy dietary patterns to choose from, the particular diet that is adopted by a given individual should be guided by their concurrent comorbidities and personal preferences. To aid in the personalization of these lifestyle recommendations, there are ongoing efforts to identify phenotypically distinct clusters, or subtypes, of gout based on comorbidities. For example, Richette et al. performed a comorbidity cluster analysis among a cohort of French patients with gout, and identified five distinct subtypes of gout as follows: 1) isolated gout with few comorbidities; 2) obesity with high prevalence of hypertension; 3) type 2 diabetes; 4) dyslipidemia; 5) cardiorenal disease.71 Similar analyses have been performed among a prospective gout cohort in the United Kingdom and using the nationally representative NHANES data in the United States.72,73 While the generalizability of these comorbidity clusters remains to be elucidated, these data suggest that personalized lifestyle counseling may be possible for patients with gout to identify the most appropriate interventions for their comorbidities and preferences (Figure 6). For example, the DASH diet may be ideal for patients with hypertension and can be implemented with calorie-restriction for those who are overweight or obese. For patients who have hypertension but have a preference for more protein in their diet, the protein-enriched DASH diet from the OmniHeart trial54 could lead to better long-term adherence. For patients who require better lipid or glycemic control, the Mediterranean diet may be most suitable based on improvements in HDL, triglycerides, and markers of insulin resistance.48

Figure 6:

Potential Personalized Approaches Based on Comorbidity Cluster Profiles

Implications on Gout Flares

Hyperuricemia is a prerequisite for developing gout and thus should be the target for the long-term management of gout; however, it is worthwhile to note the implications of diet on gout flares in the short-term. For instance, short-term exposures to purine-rich foods have been associated with recurrent gout flares in a self-controlled, case-crossover study.74 Many of the purine-rich foods assessed in this study included animal sources such as red meat and organ meats, which are to be used only sparingly according to the Healthy Eating Pyramid and cardiometabolic diets and thus, are best avoided regardless of whether one is using diet to mitigate the risk of recurrent gout flares or for long-term gout and cardiometabolic comorbidity management.

Interestingly, this case-crossover study found that consumption of high-purine foods of plant origin, such as peas, lentils, spinach, and asparagus, was not significantly associated with increased risk of recurrent gout flares.74 Again, this is compatible with the recommendations of the healthy cardiometabolic diets such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets to regularly consume legumes and vegetables. One purine-rich food item for which short- and long-term recommendations may be seemingly contradictory is seafood, which is a notable feature of the healthy cardiometabolic diets and are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids (especially fatty fish) and lean protein (both fish and shellfish).36 In an Internet-based case-crossover study, omega-3 fatty acids were associated with a reduced risk of recurrent gout flares,75 but excessive seafood consumption may nevertheless be associated with short-term increased risk of recurrent gout flares in the context of its purine content.74 Thus, it may be advisable to limit the consumption of seafood in the short-term among patients who are having frequent gout flares or during the initial phase of urate-lowering drug therapy. However, allowing seafood back into the diet is likely overall beneficial with the use of prophylactic anti-inflammatory agents such as colchicine (if needed) or once serum urate is sufficiently lowered through other means. With these maintenance measures in place, the long-term avoidance of seafood based solely on its potential to trigger recurrent gout flares (without compensatory consumption of other healthy proteins) is unadvisable, given its known cardiometabolic benefits. A similar paradigm might apply to allowing for light to moderate wine consumption, which has been associated with short-term increased risk of gout flares76 but not identified as a risk for incident gout77 or hyperuricemia.78 Furthermore, a recent randomized trial of moderate wine consumption has suggested cardiometabolic benefits.79

The Need for Further Research

As summarized, the rationale behind the cardiometabolic diets and weight loss approaches are strong and existing clinical data are very supportive; yet, high-level evidence from randomized trials specifically among gout patients are limited to date. Large-scale clinical trials of Mediterranean or DASH diets with calorie restriction among gout patients, similar to the approaches of the DIRECT trial,48 are warranted, as is further research into the effects of plant-based diets on gout risk and outcomes. Furthermore, nutrition research that incorporates patient perference and improving adherance would be highly relevant given the well-known long-term challenges in sustaining these lifestyle intervetions. A web-based educational tool called MyGoutCare, co-developed by gout patients and clinical experts, was associated with improved patient knoweledge in a pilot study,80 where it helped them identify actionable changes, including dietary changes; pilot data for GoutCare,81 a mobile application with an emphasis on diet and weight management, are also promising. While longer-term assessments of clinical endpoints are needed, these educational and self-management tools may assist patients in understanding and implementing the dietary recommendations outlined in this review.

Conclusion

In conclusion, several well-established healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets, with or without calorie restriction to achieve weight loss, can all lower serum urate levels, although the effect size is smaller than that of a typical urate-lowering drug. Cardiometabolic risk factors, including BMI, blood pressure, cholesterol profile, triglycerides, and insulin resistance, also improve with these diets (consistent with their originally proven roles), whereas such non-gout benefits remain unclear with urate-lowering drugs. Existing evidence suggests that the long-term adoption of a low-purine dietary approach for gout management is neither helpful nor sustainable for patients with gout and may have detrimental cardiometabolic consequences. A paradigm shift that considers gout as a part of the metabolic syndrome and focuses on comprehensive dietary patterns as opposed to singular food items is necessary. By focusing our dietary recommendations on dietary patterns which have been shown to reduce cardiometabolic risk factors, the beneficial effects on gout endpoints should naturally follow for the majority of typical gout cases, mediated through changes in insulin resistance. While diet alone may not supplant the need for urate-lowering therapy among patients with gout, it is a powerful adjunctive tool to comprehensively address the cardiometabolic burden and premature mortality among patients with gout.

Key Points:

Gout and hyperuricemia can be considered components of the metabolic syndrome, as insulin resistance leads to renal underexcretion of uric acid.

Gout and hyperuricemia are strongly associated with cardiometabolic comorbidities that drive the persistently elevated premature mortality observed among those with gout.

Therefore, dietary interventions that target metabolic syndrome should have the dual, synergistic effect of improving cardiometabolic risk factors while reducing the risk of gout.

Conventional guidance to follow a low-purine (i.e., low-protein) diet may be detrimental as it may lead to the increased consumption of (often refined) carbohydrates and fats (including saturated and trans fats) which can worsen gout’s cardiometabolic comorbidities and may actually contribute to hyperuricemia and gout risk.

There are several healthy dietary patterns, including the Mediterranean and DASH diets, which have been investigated in interventional or observational cohort studies and found to be beneficial both for cardiometabolic risk mitigation as well as gout and hyperuricemia.

Acknowledgements:

Financial support and sponsorship: CY is supported by T32 AR007258 and Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. NM is supported by a Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. HC is supported by R01 AR065944, P50 AR060772.

Funding:

CY is supported by T32 AR007258 and Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. NM is supported by a Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. HC is supported by R01 AR065944, P50 AR060772.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Author disclosures:

CY and NM have no disclosures. HC reports consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, Vaxart and research support from Ironwood, Horizon.

References:

- 1.Fam AG. Gout, diet, and the insulin resistance syndrome. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1350–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM, American College of P, American Physiological S. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:499–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007–2008. Am J Med 2012;125:679–87 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER 3rd, Gelber AC. Association of kidney disease with prevalent gout in the United States in 1988–1994 and 2007–2010. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;42:551–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER, Gelber AC. Dose-response association of uncontrolled blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk factors with hyperuricemia and gout. PLoS One 2013;8:e56546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessein PH, Shipton EA, Stanwix AE, Joffe BI, Ramokgadi J. Beneficial effects of weight loss associated with moderate calorie/carbohydrate restriction, and increased proportional intake of protein and unsaturated fat on serum urate and lipoprotein levels in gout: a pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:539–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ter Maaten JC, Voorburg A, Heine RJ, Ter Wee PM, Donker AJ, Gans RO. Renal handling of urate and sodium during acute physiological hyperinsulinaemia in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;92:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muscelli E, Natali A, Bianchi S, et al. Effect of insulin on renal sodium and uric acid handling in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1996;9:746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facchini F, Chen YD, Hollenbeck CB, Reaven GM. Relationship between resistance to insulin-mediated glucose uptake, urinary uric acid clearance, and plasma uric acid concentration. JAMA 1991;266:3008–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 2002;287:356–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. Am J Med 2007;120:442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi HK, De Vera MA, Krishnan E. Gout and the risk of type 2 diabetes among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1567–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker JF, Schumacher HR, Krishnan E. Serum uric acid level and risk for peripheral arterial disease: analysis of data from the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Angiology 2007;58:450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott RD, Brand FN, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan E, Baker JF, Furst DE, Schumacher HR. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2688–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan E, Svendsen K, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH, Group MR. Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HK, Curhan G. Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation 2007;116:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher MC, Rai SK, Lu N, Zhang Y, Choi HK. The unclosing premature mortality gap in gout: a general population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Lu N, Peloquin C, et al. Improved survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:408–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Cross M, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Years Lived With Disability Due to Gout and Its Attributable Risk Factors for 195 Countries and Territories 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020.** An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study which found increasing burden of gout worldwide and identified body mass index as the major modifiable risk factor that accounted for the largest proportion of years lived with disability due to gout.

- 22.Xia Y, Wu Q, Wang H, et al. Global, regional and national burden of gout, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:1529–38.** An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study which found an increasing burden of gout worldwide, especially among women.

- 23.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young LR, Nestle M. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. Am J Public Health 2002;92:246–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390:2627–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011;378:815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BF H Genetic Predictors of Obesity In: BF H, ed. Obesity Epidemiology. New York City: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi HK, McCormick N, Lu N, Rai SK, Yokose C, Zhang Y. Population Impact Attributable to Modifiable Risk Factors for Hyperuricemia. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019.** Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey which found that four modifiable risk factors (body mass index, DASH diet, alcohol use, and diuretic use) accounted for a significant proportion of hyperuricemia cases in the US general population.

- 29.Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in Adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for Aerobic Activity and Time Spent on Sedentary Behavior Among US Adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e197597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L, Cao C, Kantor ED, et al. Trends in Sedentary Behavior Among the US Population, 2001–2016. JAMA 2019;321:1587–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokose C MN, Rai SK, Lu N, Curhan G, Schwarzfuchs D, Shai I, Choi HK. Effects of Low-Fat, Mediterranean, or Low-Carbohydrate Weight Loss Diets on Serum Urate and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Secondary Analysis of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT). Diabetes Care (epub ahead of print, September 2, 2020. https://doiorg/102337/dc20-1002).* An secondary analysis of a dietary interventional trial which found that low-fat, Mediterranean, and low-carbohydrate diets could all similarly reduce serum urate as well as cardiometabolic risk factors, especially among those with baseline hyperuricemia.

- 32.Emmerson B Hyperlipidaemia in hyperuricaemia and gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:509–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2960–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang WC, Nam YH, Park SM, et al. T6092C polymorphism of SLC22A12 gene is associated with serum uric acid concentrations in Korean male subjects. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry 2008;398:140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellen PB, Gao SK, Vitolins MZ, Goff DC Jr. Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition.

- 37.Hu FB. The Mediterranean diet and mortality--olive oil and beyond. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2595–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med 2018;378:e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation 2009;119:1093–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filippatos TD, Panagiotakos DB, Georgousopoulou EN, et al. Mediterranean Diet and 10-year (2002–2012) Incidence of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease in Participants with Prediabetes: The ATTICA study. Rev Diabet Stud 2016;13:226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buckland G, Gonzalez CA, Agudo A, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of coronary heart disease in the Spanish EPIC Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:1518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, et al. Changes in Diet Quality Scores and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among US Men and Women. Circulation 2015;132:2212–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, et al. Association of Changes in Diet Quality with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. N Engl J Med 2017;377:143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Mamelle N, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet 1994;343:1454–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salas-Salvado J, Bullo M, Babio N, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2011;34:14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Koning L, Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Diet-quality scores and the risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1150–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;359:229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guasch-Ferre M, Bullo M, Babio N, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of hyperuricemia in elderly participants at high cardiovascular risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:1263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keller SRS, Lu L, Zhang Y, Choi HK. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and Mediterranean Diets and Risk of Gout in Women: 28-Year Follow-up of a Prospective Cohort [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69 (suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sacks FM, Campos H. Dietary therapy in hypertension. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 2001;344:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Appel LJ, Sacks FM, Carey VJ, et al. Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA 2005;294:2455–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belanger MWC, Mukamal K, Miller E, Sacks F, Appel L, Shmerling R, Choi H, Juraschek S. The Effects of Dietary Macronutrients on Serum Urate: A Secondary Analysis of the OmniHeart Trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020; 72 (suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/the-effects-of-dietary-macronutrients-on-serum-urate-a-secondary-analysis-of-the-omniheart-trial/. Accessed November 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Djousse L, Ho YL, Nguyen XT, et al. DASH Score and Subsequent Risk of Coronary Artery Disease: The Findings From Million Veteran Program. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liese AD, Nichols M, Sun X, D’Agostino RB Jr., Haffner SM. Adherence to the DASH Diet is inversely associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1434–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mokhtari Z, Sharafkhah M, Poustchi H, et al. Adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and risk of total and cause-specific mortality: results from the Golestan Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:1824–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parikh A, Lipsitz SR, Natarajan S. Association between a DASH-like diet and mortality in adults with hypertension: findings from a population-based follow-up study. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park YM, Fung TT, Steck SE, et al. Diet Quality and Mortality Risk in Metabolically Obese Normal-Weight Adults. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:1372–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Juraschek SP, Gelber AC, Choi HK, Appel LJ, Miller ER 3rd. Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet and Sodium Intake on Serum Uric Acid. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:3002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Juraschek SP, White K, Tang O, Yeh HC, Cooper LA, Miller ER 3rd. Effects of a Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet Intervention on Serum Uric Acid in African Americans With Hypertension. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70:1509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao Y, Cui LF, Sun YY, et al. Adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and hyperuricemia: a Cross-sectional Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rai SK, Fung TT, Lu N, Keller SF, Curhan GC, Choi HK. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, Western diet, and risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2017;357:j1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tran E, Dale HF, Jensen C, Lied GA. Effects of Plant-Based Diets on Weight Status: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2020;13:3433–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Satija A, Hu FB. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018;28:437–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chiu THT, Liu C-H, Chang C-C, Lin M-N, Lin C-L. Vegetarian diet and risk of gout in two separate prospective cohort studies. Clinical Nutrition 2020;39:837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Juraschek SP, Yokose C, McCormick N, Miller ER, Appel LJ, Choi HK. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Serum Urate: Results from the DASH Randomized Trial. Accepted for publication at Arthritis Rheum 2020.* Secondary analysis of a DASH feeding study which found that DASH diet could reduce serum urate, particularly among those with baseline hyperuricemia.

- 70.Zobbe K CR, Nielsen S, Stamp L, Henriksen M, Overgaard A, Dreyer L, Knop F, Singh J, Doherty M, Richette P, Astrup A, Ellegaard K, Bartels E, Boesen M, Gudbergsen H, Bliddal H, Kristensen L. Weight Loss as Treatment for Gout in Patients with Concomitant Obesity: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020; 72 (suppl 10) https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/weight-loss-as-treatment-for-gout-in-patients-with-concomitant-obesity-a-proof-of-concept-randomized-controlled-trial/. Accessed November 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richette P, Clerson P, Perissin L, Flipo RM, Bardin T. Revisiting comorbidities in gout: a cluster analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bevis M, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Mallen C, Hider S, Roddy E. Comorbidity clusters in people with gout: an observational cohort study with linked medical record review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:1358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yokose CLL, Chen-Xu M, Zhang Y, Choi HK. Comorbidity Patterns in Gout Using the US General Population - Cluster Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2016. Ann Rheum Dis, volume 78, supplement 2, year 2019, page A1294. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang Y, Chen C, Choi H, et al. Purine-rich foods intake and recurrent gout attacks. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1448–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang M, Zhang Y, Terkeltaub R, Chen C, Neogi T. Effect of Dietary and Supplemental Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Risk of Recurrent Gout Flares. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1580–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neogi T, Chen C, Niu J, Chaisson C, Hunter DJ, Zhang Y. Alcohol quantity and type on risk of recurrent gout attacks: an internet-based case-crossover study. Am J Med 2014;127:311–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet 2004;363:1277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi HK, Curhan G. Beer, liquor, and wine consumption and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:1023–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gepner Y, Golan R, Harman-Boehm I, et al. Effects of Initiating Moderate Alcohol Intake on Cardiometabolic Risk in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A 2-Year Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khanna P, Berrocal V, An L, Khanna D. Development and Pilot Testing of MyGoutCare: A Novel Web-Based Platform to Educate Patients With Gout. J Clin Rheumatol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kang SG, Lee EN. Development and evaluation of a self-management application for patients with gout. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2020;17:e12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]