Abstract

Background

Good adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses the viral load, reconstitutes the immune system, and decreases opportunistic infections among HIV-positive patients. However, adherence to ART is still challenging in developing countries such as Ethiopia. The study, therefore, aimed to assess adherence and its associated factors among HIV-positive patients on ART in southern Ethiopia in 2020.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 329 randomly selected participants. A structured questionnaire was used to collect the data through a face-to-face interview from January 23 to February 23, 2020. Data were entered into Epidata 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used for analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

In total, 274 patients (83.3%) had good adherence to ART, while 16.7% did not adhere. Age between 39 and 49 years old (AOR=0.068, 95% CI 0.008, 0.578), urban residency (AOR=5.186, 95% CI 1.732, 15.529), an educational status of being unable to read and write (AOR=0.097, 95% CI 0.012, 0.771), an educational status of reading and writing with no formal education (AOR=0.056, 95% CI 0.006, 0.532), comorbidity (AOR=0.042, 95% CI 0.013, 0.139), disclosure (AOR=3.583, 95% CI 1.008, 12.739), WHO clinical stage II (AOR=0.098, 95% CI 0.021, 0.453), and CD4 count ≥500 cells/mm3 (AOR=5.634, 95% CI 1.203, 26.383) were significantly associated with adherence to ART among patients.

Conclusion

The adherence of patients to ART is relatively low compared to other studies conducted in different regions. Age 39–49 years, educational status, comorbidity, and WHO clinical staging were negatively associated with ART adherence. Residency, disclosure, and current CD4 category greater than or equal to 500 cells/mm3 were positively associated with adherence. Good counseling to patients from rural areas, with low educational status, and with low CD4 counts, and on the importance of disclosure, is recommended and should be given by professionals.

Keywords: adherence, southwestern Ethiopia, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Globally, about 37.9 million people are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), among whom the largest proportion are adults, comprising 36.2 million. The emergence of HIV has taken a long time but the epidemic continues to grow and 1.7 million new infections were reported in 2018. A report from different regions indicated that there is worrying evidence of continued HIV-related mortality.1

Sub-Saharan African regions continue to have the highest incidences of HIV compared to other regions in the world.2 In 2018, about 800,000 new HIV infections were encountered in eastern and southern Africa. The deaths attributed to HIV in this region are considerable and significant, as there were 310,000 deaths in this region in 2018. There is a gap in the coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in this region; for instance, the coverage in some countries is only 9%. In this region, mortality is also attributed to the continued challenges in retaining adherence to ART.1 Ethiopia is one of the sub-Saharan African countries carrying the burden of HIV. In 2017, 722,248 adults were living with HIV.3

The initiation of a ART has significantly reduced the mortality of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWHIV) by suppressing the viral load.2,4 Early initiation and strict adherence to the antiretroviral drugs by the patients are important in the reduction of the progression of the virus to the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) state and improving the overall quality of life of the patient.5

Although there has been a dramatic change in the coverage of ART services across the globe to include low- and middle-income countries, there are still challenges in helping patients to adhere to their initiated antiretroviral drugs.6 Findings from North America showed that only 55% (n=17,573) of PLWHIV have an adherence level greater than 80%. In Africa, meta-analysis data showed that 77% of patients adhered to their medication, by considering an 80% cut-off value.7

Factors associated with adherence to the initiated antiretroviral drugs include side effects of the medications, intention to disclose the condition to others, feeling of better health condition, and socio-economic status, including educational status, residence, and income.8–12

In developing countries such as Ethiopia, adherence by HIV-positive patients to their medication is challenging.13 Being non-adherent to the medication can cause numerous problems for HIV-positive patients, including disease progression, hospitalization, and death. Moreover, non-adherence can affect the community by facilitating the transmission of HIV.14,15 In the current study site, the adherence level of patients and its contributory factors have not been determined. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the adherence level and its factors in adult HIV-positive patients taking ART in southern Ethiopia in 2020.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Design

The study was conducted in Gebre-Tsadik Shawo General Hospital (GTSGH) and Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospitals (MTUTH). GTSGH is a governmental hospital located in Bonga, 452.54 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. At the time of data collection, there were 1409 adult HIV-positive patients receiving their antiretroviral medications in GTSGH. MTUTH is located 568.4 km from Addis Ababa. During the time of data collection, there were a total of 1629 adult HIV-positive patients receiving their antiretroviral medications in MTUTH. An institutional-based quantitative cross-sectional study design was conducted from January 23 to February 23, 2020.

Source Population

The source population comprised adult HIV-positive patients following treatment at the ART clinics of MTUTH and GTSGH.

Study Participants

Study participants were sampled adult HIV-positive patients following treatment at the ART clinics of MTUTH and GTSGH during the time of data collection.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All adult HIV-positive patients following their treatment at the ART clinics of MTUTH and GTSGH during the time of data collection were included. Severely ill patients from other medical causes who were linked to the medical treatment department, and those aged less than 18 years old, were excluded from the study.

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula. Based on the assumption of a 95% confidence interval, a 5% margin of error, the proportion of adherence to ART being 73%,16 and a 10% non-response rate, a total sample of 333 was needed.

A systematic random sampling method was used to select study participants. First, the source population in each hospital was identified; during the time of data collection, there was a total of 1629 adult HIV-positive patients taking antiretroviral drugs in MTUTH. Similarly, there was a total of 1409 adult HIV-positive patients taking antiretroviral drugs in GTSGH. To obtain 333 study participants, a proportional allocation was made to each hospital, and in that way, 179 samples were from MTUTH and 154 were from GTSGH. The sampling interval (K-th) for each hospital was determined by dividing the source population in each hospital into proportionally allocated samples in each hospital. For each hospital, the sampling interval (K-th) was 9. To obtain the first participant for the data collection, from 1 to 9, number 3 was randomly selected, and on each day of data collection, the third attending patient was the starting point of data collection. On each day of data collection, the third patient was taken as the first sample, and then every ninth interval was taken to conduct an interview until the required sample size was acquired. In both settings, patients taking antiretroviral drugs are provided with their monthly medications and attend monthly appointments. Unless patients have contracted other medical illnesses, it is unlikely that they would visit the hospital before the due appointment date.

Data Collection Tool, Quality Control, and Procedure

The questionnaire for this study was developed based on previous relevant studies which were conducted in other parts of Ethiopia with a similar purpose.16,17 The structured questionnaire, which was first designed in English, was translated to the Amharic version, which is the local language, to make it clearer and easier to understand. The questionnaire had the following essential components: socio-demographic characteristics, clinical variables, and behavioral variables. A one-day orientation on data collection was given to four data-collector diploma nurses. Before actual data collection, the questionnaire was pretested on 17 patients attending Wacha primary hospital, a different hospital from the current study sites, and necessary corrections were made before using it for the actual study. The face-to-face interviews were conducted by four diploma nurses who collected the data.

ART adherence was measured by recording the total number of pills taken in one full month.18,19 In addition to recording the patient’s report, data collectors checked the total number of pills that a patient had taken from a total of 30 pills, and cross-matching was done for checking purposes and to reduce potential recall bias. To determine the adherence level for each participant, the actual number of pills taken by a patient was divided by the total number of pills to be taken (30), which was then multiplied by 100%. The adherence status was dichotomized to adherence to ART, if participants scored above or equal to 95%, and otherwise non-adherence.20 Furthermore, participants who did not adhere were dichotomized to fair and poor adherence by taking 85% as the cut-off value.13,20

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were entered into Epidata 3.1 version after a manual check for completeness, skip pattern, and wrong coding, which was corrected at the study site. The entered data were exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis. Descriptive statistics using a table of frequency distribution were used to summarize the results, such as socio-demographic characteristics, and clinical and behavioral variables. Then, the data were presented using sentences, graphs, tables, frequencies, and percentages. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to identify the independent predictors of ART adherence. Crude odds ratios (CORs) were used to explain the strength of association between factors and dependent variables at p<0.25 for bivariate logistics, and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were used to describe the strength of association between the factors and dependent variables in multivariate logistics at p<0.05.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and a formal letter was obtained to conduct the study from the Nursing Department, Mizan Tepi University. The administration offices of both hospitals were informed about the purpose of the study to obtain permission. Confidentiality of the respondents was secured by excluding respondents’ identifiers, such as names, from the data collection format. Informed written consent was obtained from the respondents before conducting the study.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Out of 333 participants, 329 were involved in the study, making a response rate of 98.8%. The mean age of the participants was 35.19 years, with the minimum of 18 years and maximum of 60 years old. The majority (43.8%) of study participants were in the age category 28–38 years old, while 171 (52.0%) were females and 77.2% of them were from urban areas. Regarding the ethnicity, the majority (58.7) were Kaffa; 301 (91.5%) were living with family, 47.1% had attended primary education, and the majority (66.9%) were married (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Patients Who Were on ART at GTSGH and MTUTH, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age category | 18–28 | 73 | 22.2 |

| 29–39 | 144 | 43.8 | |

| 40–49 | 86 | 26.1 | |

| ≥50 | 26 | 7.9 | |

| Gender | Male | 158 | 48.0 |

| Female | 171 | 52.0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 61 | 18.5 |

| Married | 220 | 66.9 | |

| Divorced | 45 | 13.7 | |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.9 | |

| Living with family | Yes | 301 | 91.5 |

| No | 28 | 8.5 | |

| Residence | Urban | 254 | 77.2 |

| Rural | 75 | 22.8 | |

| Educational status | Cannot read and write | 57 | 17.3 |

| Able to read and write | 35 | 10.6 | |

| Primary school | 155 | 47.1 | |

| Secondary school | 57 | 17.3 | |

| Higher education | 25 | 7.6 | |

| Ethnicity | Kaffa | 193 | 58.7 |

| Amhara | 57 | 17.3 | |

| Oromo | 11 | 3.3 | |

| Bench | 34 | 10.3 | |

| Sheko | 12 | 3.6 | |

| Others* | 22 | 6.7 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 186 | 56.5 |

| Muslim | 52 | 15.8 | |

| Protestant | 85 | 25.8 | |

| Catholic | 6 | 1.8 | |

| Monthly income in ETB | <1000 | 125 | 38.0 |

| 1000–3000 | 122 | 37 | |

| >3000 | 82 | 25 | |

| Occupational status | Housewife | 92 | 28.0 |

| Farmer | 72 | 21.9 | |

| Government employee | 75 | 22.8 | |

| Merchant | 37 | 11.2 | |

| Student | 17 | 5.2 | |

| Sex worker | 8 | 2.4 | |

| Daily laborer | 28 | 8.5 | |

Note: Ethnicity others*: Tigre, Majang, Menit, Gurage.

Clinical and Behavioral Characteristics of Participants

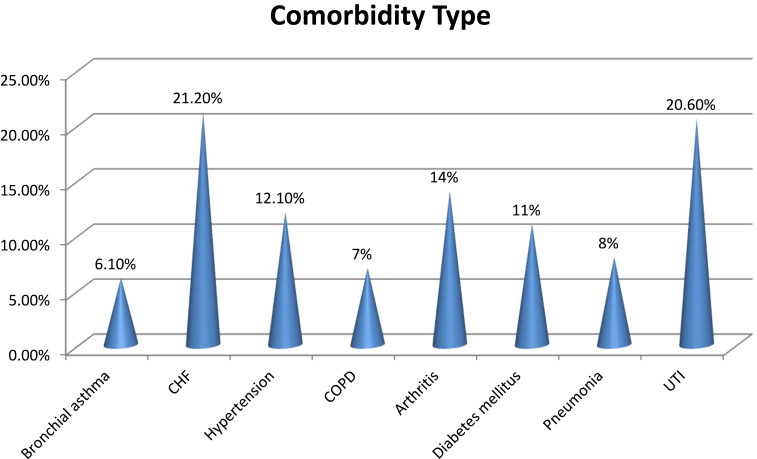

The majority (69.9%) of participants had no comorbid conditions, while 90% were in WHO clinical stage I and 45.9% had current cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) levels of 200–499 cells/mm3. Among those with comorbidity, 21 (21.2%) had chronic heart failure, 20 (20.6%) had urinary tract infection, and 14 (14%) had arthritis (Figure 1). Moreover, 147 (44.7%) of the study participants had an initial CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3, 291 (88.4%) were taking TDF, 3TC, and EFV, and 240 (72.9%) had a duration of disease greater than or equal to 25 months. Two-hundred and five (62.3%) had no family history of HIV, and all of the participants had information about the purpose of the drugs that they were taking. Most patients (84.2%) had experienced side effects of the drugs, while 316 (96.0%) did not have current side effects from the medications and 216 (65.7%) were self-memorizing for taking medications. Two-hundred and eighty-five patients (86.6%) had disclosed their HIV status to their family, and 298 (90.6%) had not attempted any alternative treatments other than ART; the majority (91.5%) had not had multiple sexual partners, while 288 (87.5%) were non-drinkers and only 14 (4.3%) were smokers (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Comorbid types among patients who were on ART at GTSGH and MTUTH, southwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Table 2.

Clinical and Behavioral Characteristics of Patients Who Were on ART at GTSGH and MTUTH, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | Yes | 99 | 30.1 |

| No | 230 | 69.9 | |

| Duration of illness | <12 months | 26 | 7.9 |

| 12–24 months | 63 | 19.1 | |

| ≥25 months | 240 | 72.9 | |

| Family history of HIV | Yes | 124 | 37.7 |

| No | 205 | 62.3 | |

| Current WHO clinical stage | I | 296 | 90.0 |

| II | 24 | 7.3 | |

| III | 9 | 2.7 | |

| Initial CD4 category | <200 cells/mm3 | 147 | 44.7 |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 142 | 43.2 | |

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 40 | 12.2 | |

| Current CD4 category | <200 cells/mm3 | 53 | 16.1 |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 151 | 45.9 | |

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 125 | 38.0 | |

| Ever had side effects of ART | Yes | 277 | 84.2 |

| No | 52 | 15.8 | |

| Current side effects of ART | Yes | 13 | 4.0 |

| No | 316 | 96.0 | |

| Current ART regimen | TDF, 3TC, EFV | 291 | 88.4 |

| TDF, 3TC, NVP | 8 | 2.4 | |

| AZT, 3TC, NVP | 17 | 5.2 | |

| AZT, 3TC, EFV | 13 | 3.9 | |

| Who reminds to take ART | Self | 216 | 65.7 |

| Alarm | 78 | 23.7 | |

| Family members | 19 | 5.8 | |

| Radio/television | 16 | 4.9 | |

| Treatment other than ART | Yes | 31 | 9.4 |

| No | 298 | 90.6 | |

| Treatment other than ART | Traditional drug | 12 | 38.7 |

| Religious practice, eg, Tsebel | 19 | 61.3 | |

| Disclosure to family/others | Yes | 285 | 86.6 |

| No | 44 | 13.4 | |

| Current smoking | Yes | 14 | 4.3 |

| No | 315 | 95.7 | |

| Current alcohol drinking | Yes | 41 | 12.5 |

| No | 288 | 87.5 | |

| Ever had multiple sexual partners | Yes | 28 | 8.5 |

| No | 301 | 91.5 |

Abbreviations: TDF, tenofovir; 3TC, lamivudine; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; AZT, zidovudine.

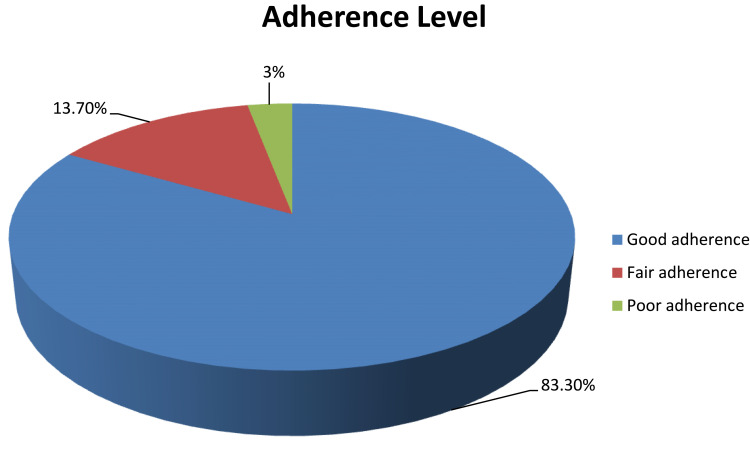

Adherence Level of Participants to ART

In this study, 274 patients (83.3%) had adherence levels greater than or equal to 95% and were considered as adherent to ART, and 55 (16.7%) were not adherent to ART (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adherence levels of patients to ART at GTSGH and MTUTH, southwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Factors Associated with Adherence of Patients to ART

In bivariate logistics regression, age category, sex, residency, educational status, comorbidity, disclosure, smoking, duration of illness, WHO clinical staging, current CD4 count, and using alternative methods other than ART were significantly associated with adherence to ART care at p<0.25. All of these variables were moved to the multivariate logistics analysis and a significant association was considered at p<0.05. Multivariate logistics regression showed that patients in the age category 39–40 years old were 93% times less likely to adhere to their ART care compared to those in the age category 18–27 years old (AOR=0.068, 95% CI 0.008, 0.578). Patients from urban areas who were seropositive for retroviral infections were five times more likely to adhere to ART care than patients from rural areas (AOR=5.186, 95% CI 1.732, 15.529). HIV-positive patients who were unable to read and write were 90% times less likely to adhere to ART care compared to those with a higher level of education (AOR=0.097, 95% CI 0.012, 0.771). Patients who had other comorbid diseases were 96% times less likely to adhere to ART care than those without comorbid diseases (AOR=0.042, 95%CI 0.013, 0.139). HIV-positive patients who had disclosed their HIV status to their family and others were almost four times more likely to adhere to their ART than patients who had not disclosed their status to others (AOR= 3.583, 95% CI 1.008, 12.739). The odds of adherence to ART care among WHO clinical stage II patients were 90% times lower than in WHO clinical stage I patients (AOR=0.098, 95% CI 0.021, 0.453). The odds of adherence to ART care among patients with CD4 category ≥500 cells/m3 were almost six times higher than in patients with CD4 category below 200 cells/m3 (AOR=5.634, 95% CI 1.203, 26.383) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors Associated with Adherence to ART Among Patients in GTSGH and MTUTH, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020

| Variables | Category | Adherence Status to ART Care | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Adherent (%) | Adherent (%) | ||||

| Age category | 18–27 | 4 (7%) | 69 (25.2%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 28–38 | 19 (34.5%) | 125 (45.6%) | 0.381 (0.125, 1.166) | 0.836 (0.108, 6.501) | |

| 39–49 | 31 (56.4%) | 55 (20.1%) | 0.103 (0.034, 0.309)* | 0.068 (0.008, 0.578)** | |

| ≥50 | 1 (1.8%) | 25 (9.1%) | 1.449 (0.155, 13.594) | 8.107 (0.190, 346.524) | |

| Sex | Male | 35 (63.6%) | 123 (44.9%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Female | 20 (36.4%) | 151 (55.1%) | 2.148 (1.181, 3.910)* | 2.543 (0.885, 7.306) | |

| Residence | Urban | 24 (43.6%) | 230 (83.9%) | 6.752 (3.622, 12.588)* | 5.186 (1.732, 15.529)** |

| Rural | 31 (56.4%) | 44 (16.1%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 21 (38.2%) | 36 (13.1%) | 0.234 (0.062, 0.876)* | 0.097 (0.012, 0.771)** |

| Able to write and read without formal education | 13 (23.6%) | 22 (8%) | 0.231 (0.058, 0.924)* | 0.056 (0.006, 0.532)** | |

| Primary education | 11 (20%) | 144 (52.6%) | 1.785 (0.461, 6.908) | 0.902 (0.126, 6.451) | |

| Secondary education | 7 (12.7%) | 50 (18.2%) | 0.974 (0.230, 4.121) | 0.216 (0.019, 2.461) | |

| Higher education | 3 (5.5%) | 22 (8.1%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Smoking | Yes | 4 (7.3%) | 10 (3.6%) | 0.483 (0.146, 1.600)* | 0.811 (0.081, 8.097) |

| No | 51 (92.7%) | 264 (96.4%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Duration of illness | <12 months | 2 (3.6%) | 24 (8.7%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 12–24 months | 12 (21.8%) | 51 (18.7%) | 0.354 (0.073, 1.709)* | 0.240 (0.007, 8.069) | |

| ≥25 months | 41 (74.6%) | 199 (72.6%) | 0.404 (0.092, 1.779)* | 0.198 (0.007, 5.359) | |

| Comorbidity | Yes | 43 (78.2%) | 56 (20.4%) | 0.072 (0.035, 0.145)* | 0.042 (0.013, 0.139)** |

| No | 12 (21.8%) | 218 (79.6%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

| Disclosure of HIV | Yes | 39 (70.9%) | 246 (89.8%) | 3.604 (1.788, 7.266)* | 3.583 (1.008, 12.739)** |

| No | 16 (29.1%) | 28 (10.2%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

| WHO clinical stage | Stage I | 36 (65.5%) | 260 (94.9%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Stage II | 13 (23.6%) | 11 (4%) | 0.117 (0.049, 0.281)* | 0.098 (0.021, 0.453)** | |

| Stage III | 6 (10.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.069 (0.017, 0.289)* | 0.004 (0.001, 0.075)** | |

| Current CD4 category | <200 cells/mm3 | 13 (23.6%) | 40 (14.6%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 29 (52.7%) | 122 (44.5%) | 1.367 (0.649, 2.881) | 0.853 (0.237, 3.066) | |

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 13 (23.6%) | 112 (40.9%) | 2.800 (1.198, 6.546)* | 5.634 (1.203, 26.383)** | |

| Treatment other than ART | Yes | 13 (23.6%) | 18 (6.6%) | 0.227 (0.104, 0.498)* | 1.161 (0.277, 4.861) |

| No | 42 (76.4%) | 256 (93.4%) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | |

Notes: *Significantly associated at p<0.25; **significantly associated at p<0.05.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ART, antiretroviral therapy; COR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Discussion

The study aimed to assess adherence to ART and its associated factors among HIV-positive patients in southwestern Ethiopia. The study identified that 83.3% of patients adhered to ART, while the remaining 16.7% adhered below the 95% adherence rate. Thus, 83.3% of patients had good adherence, 13.7% had fair adherence, and 3% had poor adherence to ART. The finding of this study, which indicated 83.3% good adherence, is lower than in studies conducted in southeastern Nigeria and Lagos Island, Nigeria, where 97.9% and 90% of patients had good adherence.21,22 The finding was also lower than in studies conducted in other regions of Ethiopia, for example 90.8% had good adherence in Gobba,23 88.2% had good adherence in Gondar referral hospital,24 and 95.5% had good adherence in Ambo.25 A possible explanation for these variations may be the difference in socio-economic status, as the current study area is in a relatively rural part of the country compared to the other areas. This finding is, however, better than in studies done in Nigeria (74.2%),26 Yirgalem Hospital of Ethiopia (63.8%),27 and Peru (41.7%).28 The explanation for this variation, particularly from the study in Peru, may be differences in sample sizes, with a small sample being used in Peru, and differences in the tools used for assessing adherence.

The study showed that the odds of adherence to ART among patients in the age group 39–49 years old were almost 93% times lower than in the age group 18–27 years old (AOR=0.068, 95% CI 0.008, 0.578). But there were no significant associations with adherence in other age groups, such as 28–38 years old and ≥50 years old, and most of the studies did not identify any significant associations between age group and perfect adherence.21,29 The significantly associated age group (18–27 years) determined in this study is in contrast with a previous study in Kenya, where adherence to ART increased as the age increased, up to age 60.30 This finding is consistent with other studies in Rwanda and Ethiopia, which stated that there was no perfect adherence in lower age groups, including 35–44 years old.16,31 The possible reason for such variation may be due to adherence in such lower age groups to counseling services given by care providers in regard to drug adherence. A considerable period for counseling in regard to ART adherence has to be given during the initiation of ART, and in this study, large numbers of participants had lived with HIV for a long time.

This study also found that the odds of adherence to ART among patients from urban areas were five times higher than in those from rural areas (AOR=5.186, 95% CI 1.732, 15.529). This is consistent with the study conducted in Gondar.23 The justification for this finding may be that patients from urban areas have easy access to information about the importance of strict adherence to ART, and such patients may have good educational status. The justification given in regard to education could be that patients with good educational status are better at adhering than those with poor educational status, and it is clear that individuals with good educational status live in urban areas of Ethiopia. The study also identified that the odds of adherence among HIV-positive patients who were unable to write and read were almost 90% times lower compared to those HIV-positive patients with higher educational status. Similarly, the odds of adherence among HIV-positive patients who were able to write and read were almost 94% times lower compared to those HIV-positive patients with higher educational status. This is consistent with a study from Harari, Ethiopia.16

The study pointed out that patients with other comorbid diseases were almost 96% times less likely to adhere to ART care than those without comorbid diseases (AOR=0. 042, 95% CI 0.013, 0.139). This finding is supported by a study from Gondar.23 Patients with multiple health problems may miss their daily drugs to avoid the self-perceived side effects of taking many medications. Being tired of comorbid disease conditions may limit patients from taking ART drugs.32 The study also identified that HIV-positive patients who disclosed their HIV status to their family and others were almost four times more likely to adhere to their ART than patients who did not disclose their status to others (AOR=3.583, 95% CI 1.008, 12.739). This is supported by the findings of a meta-analysis33 and a study from Nigeria.34 A possible reason for this association is that patients who have disclosed their status to their family can take their medications without fear, with good social support and appropriate financial support from their family35

This study also showed that the odds of adherence among patients with WHO clinical stage II were 90% lower than in those with WHO clinical stage I. Similarly, the odds of adherence among patients with WHO clinical stage III were 99% lower than in those with WHO stage I. This finding is not in line with a study conducted in northeast Ethiopia, in which there was no significant association between WHO clinical staging and adherence status.36 The study also found that patients with a current CD4 category greater than or equal to 500 cells/mm3 were five times more adherent than those with CD4 of below 200 cells/mm3. This is supported by other studies, which found that strict adherence can bring about immune reconstitution and rebuilding.23,37–40

Limitations

The study was purely quantitative and did not assess the factors that affected adherence through qualitative study. Therefore, a qualitative study is recommended. The present study also only identified factors associated with the adherence but did not assess causality. Therefore, instrumental variable analysis is recommended to illustrate causality and improve the management of HIV-positive patients.

Conclusions

The adherence level of patients to ART is good, even if it was below that found in other studies conducted in other regions of Ethiopia. Being in the age group 39–49 years, educational status, comorbidity, and WHO clinical staging were negatively associated with ART adherence. Residency, disclosure, and current CD4 categories greater than or equal to 500 cells/mm3 were positively associated with adherence. Good counseling, particularly to patients from rural areas, those with low educational status, and those with lower CD4 counts, and counseling on the importance of disclosure, is recommended and should be given by professionals during care at the ART clinic.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all study participants for their commitment in responding to questionnaires and all data collectors for their collaboration up to the end of the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Science Panel. Making the End of AIDS Real: Consensus Building Around What We Mean by “Epidemic Control”. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2018. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/glion_oct2017_meeting_report_en.pdf. Accessed 4July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nation program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Prevention Gap Report. Geneva: unaids.org; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.HAPCO. HIV prevention in Ethiopia National Road map; 2018. https://ethiopia.unfpa.org/en/hiv-prevention-ethiopia-national-road-map. Available from:Accessed 25September 2018.

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. United Nation AIDS World AIDS Day Report 2011 (Faster, Smarter, Better). Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel G, Nwokike J, Joshi MP. Development of a Multi-Method Tool to Measure ART Adherence in Resource-Constrained Settings: The South Africa Experience. RPM Plus. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morowatisharifabad MA, Movahed E, Nikooie R, et al. Adherence to medication and physical activity among people living with HIV/AIDS. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24(5):397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(6):679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juday T, Gupta S, Grimm K, Wagner S, Kim E. Factors associated with complete adherence to HIV combination antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12(2):71–78. doi: 10.1310/hct1202-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falagas ME, Zarkadoulia EA, Pliatsika PA, Panos G. Socioeconomic status (SES) as a determinant of adherence to treatment in HIV infected patients: a systematic review of the literature. Retrovirology. 2008;5(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson MJ, Petrozzino JJ. An evidence-based review of treatment-related determinants of patients’ nonadherence to HIV medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(11):903–914. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arrivillaga M, Ross M, Useche B, Alzate ML, Correa D. Social position, gender role, and treatment adherence among Colombian women living with HIV/AIDS: social determinants of health approach. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;26(6):502–510. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892009001200005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asmare M, Aychiluhem M, Ayana M, Jara D. Level of ART adherence and associated factors among HIV sero-positive adult on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 2014;6:120–126. doi: 10.4172/jaa.10000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baggaley RF, White RG, Hollingsworth TD, Boily MC. Heterosexual HIV-1 infectiousness and antiretroviral use: systematic review of prospective studies of discordant couples. Epidemiology. 2013;24(1):110–121. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276cad7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitiku H, Abdosh T, Teklemariam Z. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Harari National Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. ISRN AIDS. 2013;2013:960954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berhe B, Yigzaw K, Melaku K, Desalegn T, Mebrahtu A, Yalemzewod A. Determinants to antiretroviral treatment non‑adherence among adult HIV/AIDS patients in northern Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR–4):1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machtinger EL, Bangsberg DR Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy HIV InSite Knowledge Base chapter. 2006.

- 20.Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) Ethiopia. National Consolidated Guidelines for Comprehensive Hiv Prevention, Care and Treatment. Addis Ababa: FMOH Ethiopia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugochukwu U, Onyeonoro UUEU, Ibeh CC, Nwamoh UN, Ukegbu AU, Emelumadu OF. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a tertiary health facility in South Eastern Nigeria. J HIV Hum. 2013;1(2):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adekemi O, Sekoni OR, Obidik BM. Stigma, medication adherence and coping mechanism among people living with HIV attending General Hospital, Lagos Island, Nigeria. Prm Health Care Fam. 2012;1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molla AA, Gelagay AA, Mekonnen HS, Teshome D. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and associated factors among HIV positive adults attending care and treatment in University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3176-8.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teshome W, Belayneh M, Moges M, et al. Who Takes the Medicine? Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Southern Ethiopia. Vol. 2015 Dove Medical Press Limited; 2015:1531–1537. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fituma S, Tsegaye D. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among people living with HIV In Ambo Hospital, West Shewa Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2016;5(Issue 2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moses Kayode O, et al. Investigation of factors affecting medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS under Non-Governmental Organizations in Ibadan City, Nigeria. JPBMS. 2012;21(21):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markos E, Worku A, Davey G. Adherence to ART in PLWHA at Yirgalem Hospital, SouthEthiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;22:2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leyva-Moral JM, Loayza-Enriquez BK, Palmieri PA, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and the associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Peru: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2019;16:22. doi: 10.1186/s12981-019-0238-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abera A, Fenti B, Tesfaye T, Balcha F. Factors Influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS at art clinic in Jimma University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. J Pharma. 2015;1(1):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anthony N Factors that influence non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV and AIDs patients in central province, Kenya; 2011. Available from: http://ir-library.ku.ac.ke/handle/123456789/1725. Accessed August21, 2020.

- 31.Elul B, Basinga P, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, et al. High levels of adherence and viral suppression in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy for 6, 12 and 18 months in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kranzer K, Ford N. Unstructured treatment interruption of antiretroviral therapy in clinical practice: a systematic review. Tropical Med Int Health. 2011;16:1297–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dessie G, Wagnew F, Mulugeta H, et al. The effect of disclosure on adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adults living with HIV in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:528. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4148-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pennap GR, Abdullahi U, Bako IA. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and its challenges in people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in Keffi, Nigeria. JAHR. 2013;5(2):52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tshweneagae GT, Oss VM, Mgutshini T. Disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners by people living with HIV. curationis. 2015;38(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mengistie A, Birhane A, Tesfahun E. Assessment of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adult people living with HIV/AIDS in North East, Ethiopia. Appl Microb Res. 2019;2(2):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fonsah JY, Njamnshi AK, Kouanfack C, et al. Adherence to antire troviral therapy (ART) in yaounde´-cameroon: association with opportunistic infections, depression, ART regimen and side effects. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Zhou J, Zhou J, et al. Consistent ART adherence is associated with improved quality of life, CD4 counts, and reduced tal costs in Central China. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2009;25(8):757–763. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nachega J, Morroni CR, Efron GR, Ram M. Impact of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome on antiretroviral therapy adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:887–891. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S38897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhasmana DJ, Dheda K, Ravn P, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2008;68:191–208. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868020-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]