Abstract

Human functional brain networks can be reliably characterized within individuals using precision functional mapping. This approach entails the collection of large quantities of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from each individual subject. Studies employing precision functional mapping in the cerebral cortex have found that individuals manifest unique representations of functional brain networks around a central tendency described by previous group average approaches. We recently extended precision functional mapping to the subcortex and cerebellum, which has revealed several novel organizational principles within these structures. Here, we detail these principles and provide insights into how precision functional mapping of subcortical structures and the cerebellum may become clinically translatable.

Keywords: Basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, functional connectivity, fMRI, resting state, brain networks, individual variability, deep brain stimulation

Introduction

Repeated sampling of individual human brain function with fMRI, termed “precision functional mapping,” has enabled the reliable description of functional brain organization within individual people. Precision functional mapping refers to the collection of large quantities (hours) of fMRI data from each individual subject. Most recent precision functional mapping studies have utilized resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC), in which fMRI data are collected while an individual is at rest (i.e., not engaged in a specific task) inside an MRI scanner. The correlated spontaneous activity measured with RSFC is organized into reproducible functional networks that resemble patterns of task-induced brain activity, such as those related to vision, somatomotor function, and attention [1,2]. Collecting large quantities (>45 mins) of RSFC data with precision functional mapping results in massive improvements in single-subject RSFC reliability [3]. This approach stands in contrast to the standard methods of group averaging, in which small quantities (e.g., 10 mins) of RSFC data are collected across tens or hundreds of subjects and averaged together. Such group average approaches result in very reliable central tendencies of functional brain network organization [4–8], though poor reliability within a single individual. Group averaging also masks individual variability in functional organization around this central tendency [3,9,10]. Thus, a particular anatomical location in one individual may belong to a functional network that differs from the group average. While both group-average and individualized approaches have utility, individualized approaches may provide more leverage for clinical utility of fMRI.

Precision functional mapping was kickstarted by The MyConnectome Project [3], in which Dr. Russel Poldrack scanned himself for 10 minutes, twice per week over the course of 18 months. This endeavor established the finding of increased reliability with large quantities of data. Additional datasets with slightly larger sample sizes followed suit, including the Midnight Scan Club (n=10) [10] and individuals reported by Braga et al. [9] (n=4). However, these studies focused solely on the cerebral cortex. Given the importance of other brain structures, including the subcortex and cerebellum, and their known connectivity with the cortex, precision functional mapping could prove useful for interrogating subcortical and cerebellar functional organization. This idea brought up the question of whether we could reliably measure RSFC between the cortex and subcortical/cerebellar structures, given the relatively poorer signal-to-noise ratio in fMRI data in some of these regions. If we could, would these structures also demonstrate individual variability around the central tendency? What other organizational principles could be uncovered?

In Greene et al., 2020 [11] and Marek et al., 2018 [11,12], we set out to answer these questions with respect to the subcortex and cerebellum, respectively. In addition, several other recent papers have begun to contribute knowledge concerning individual-specific organization of these structures. In this review, we will summarize the novel organizational principles we discovered in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum. We will also discuss clinical implications, some of which may be imminently applicable.

Basal Ganglia and Thalamus

The basal ganglia and thalamus interconnect the cerebral cortex via cortico-striato-thalamic and cortico-thalamo-cortical loops [13,14]. Because of their hub-like centrality, the basal ganglia and thalamus have been shown to play a role in many neurological and psychiatric disorders. Although classic models of cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loops describe segregated, parallel circuits that support discrete functions [13], there is mounting evidence for integration between circuits within the subcortex from distal cortical projections [15–17], as well as from the cerebellum [18]. Thus, more recent theoretical frameworks of the subcortex include convergence zones that integrate processes of executive control, reward processing, and spatial attention [17,19]. Results from group average neuroimaging studies have been interpreted to support the integrative framework of subcortical organization, such that multiple cortical functional networks converge within the basal ganglia and thalamus [19–21]. However, with group average studies, it is hard to disentangle if network integration is real or a product of methodological artifact, namely the spatial blurring that stems from averaging data from many people together. Thus, establishing the existence of integrated functional neuroanatomy requires reliable, individual-level data.

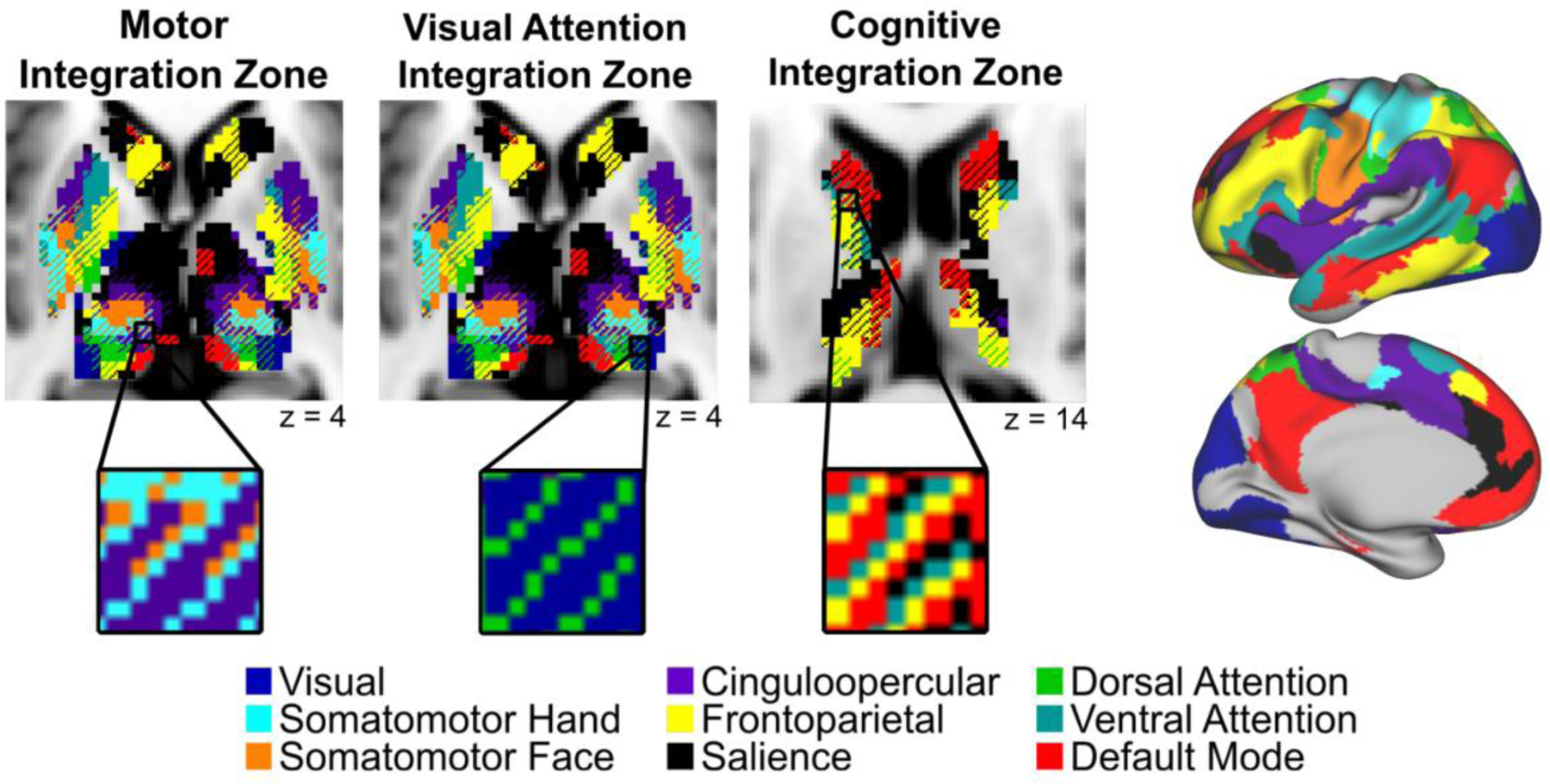

In Greene et al. [11], we aimed to characterize functional organization of the basal ganglia and thalamus along two principal axes: segregation vs. integration (RSFC with one vs. multiple cortical networks) and group vs. individual (consistent organization vs. variable organization across individuals). Similar to the cerebral cortex, obtaining reliable RSFC data in the subcortex was possible, but required more data than the cortex, specifically ~100 minutes of denoised (motion-censored) data per individual. Results supported the presence of both segregated and integrative functional circuits, fitting with the updated models from animal work. Integration of functional networks in the subcortex was systematic, such that three types of integration zones combining distinct functional networks existed in focal subcortical regions (Figure 1). These zones included: (i) motor integration zones in the ventral intermediate portion of the thalamus, in which there was convergence of the cingulo-opercular control network and somatomotor networks; (ii) visual attention integration zones corresponding to the location of the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus, in which there was convergence of the dorsal attention and visual networks; and (iii) cognitive integration zones in the head of the caudate, putamen, pallidum, and dorsal thalamus, in which there was convergence of multiple control networks and the default mode network.

Figure 1. Subcortical integration zones.

(Left) The basal ganglia and thalamus contain three distinct functional integration zones: motor, visual attention, and cognitive (from left to right). Insets depict the functional networks that converge within each integration zone. (Right) MSC average functional network representations in the cerebral cortex. Figure adapted from Greene et al., [9].

The motor integration and visual attention integration zones were quite consistent across individual subjects (i.e., the same networks converged in these regions in nearly all individuals). The nature of the motor integration zones in the thalamus suggests that the cingulo-opercular network might exert some level of control over motor outputs via the thalamus. Most research interrogating the role of the cingulo-opercular network supports the idea that it is primarily involved in stable maintenance of task control [22–25]. Building on this view, recent work from our labs suggest the cingulo-opercular network plays a central role in motor system plasticity in humans [26,27]. Further, data from stroke patients suggest that some cingulo-opercular regions are necessary for executing motor functions [28]. Taken together, the cingulo-opercular network interacts with somatomotor networks in a way that has not been demonstrated in other control networks. Our results suggest that the motor integration zone in the thalamus is a potential key node for the integration of these networks.

The visual attention integration zones in the posterior thalamus were consistent with previous work in non-human primates, as the pulvinar nucleus is known to be involved in vision as well as attentional selection of visual information [29–31]. Thus, our results suggest that the posterior thalamus may be the site of coordination of the visual and dorsal attention networks to carry out such selection.

The cognitive integration zones included some anatomical regions (head of the caudate, dorsal thalamus) with consistency across subjects, but other regions (putamen, pallidum) that were quite individually variable (i.e., different networks converging in different subjects). The consistent integration zones in the caudate overlap well with non-human primate studies showing converging projections from multiple frontal regions, which fall within the networks showing convergence [15]. In the individually variable cognitive integration zones (within the putamen and pallidum), different control networks converged in the same anatomical location across individuals. For example, in the putamen, some subjects showed convergence of the default mode and cingulo-opercular networks, whereas others showed convergence of the frontoparietal and salience networks.

Importantly, the distinction between regions showing individual variability vs. consistency across subjects was made possible only by using a precision functional mapping approach. Further, this individual-level approach lends convincing evidence to the identification of subregions with integration (representation of multiple networks) above and beyond that of group-level studies. When a group of individuals are averaged together, individual-level data are warped to a common template and spatially smoothed, inducing some degree of spatial blurring. Therefore, the appearance of network integration could spuriously result from this warping step. With precision functional mapping, we avoid this step, circumventing concerns of apparent integration resulting from averaging, and bolstering confidence in the finding of integration zones.

Cerebellum

The human cerebellum, though vastly understudied compared to the cerebral cortex, contains the majority of the brain’s neurons [32] and has a surface area ⅘ of the cerebral cortex [33]. In humans, the lateral portions of the cerebellum (Crus I/II) are disproportionately expanded [33,34]. Work in macaques has shown that the lateral cerebellum forms polysynaptic closed-looped circuits with regions of the prefrontal and posterior parietal cortex [35,36]. Paralleling anatomical tracing work in non-human primates, seminal work in group-average human fMRI studies has similarly concluded that the cerebellum exhibits correlated spontaneous BOLD activity between the lateral cerebellum and association areas of the cerebral cortex dedicated to attention and control. Moreover, cerebellar BOLD activity increases in response to working memory, attention, and language tasks [37,38].

Similar to the basal ganglia and thalamus, in Marek et al. [12] we were interested in characterizing the functional organization of the cerebellum at the individual level using precision functional mapping. First, we established that RSFC between the cerebellum and cortical networks can be measured reliably within individuals, achieving excellent split-half reliability with 90 minutes of data. Similar to the subcortex, we found functional network organization within the cerebellum in individuals that was consistent with prior knowledge of this organization (Figure 2A). However, in stark contrast to the subcortex, networks within the cerebellum were functionally segregated and exhibited sharp boundaries between networks. Motor network (foot, hand, face) representations were restricted to the most anterior regions of the cerebellum, with a second inverted representation in the posterior lobes, while the lateral lobes (Crus I/II) contained representations of attention and control networks, as well as the default mode network. A subsequent study mapping the cerebellum in two individual humans revealed similar organization, as well as representation of the visual cortex within the vermis [39]. Although the general gestalt of functional network organization was similar across the 10 individuals we studied, measurable deviations were observed. Thus, group average studies inherently blur functionally distinct networks together, which can distort the functional neuroanatomy that may be subsequently used to study individual differences in behavioral phenotypes.

Figure 2. Individual functional network representations in the cerebellum.

(A) Cerebellar functional network representations in two representative individuals from the Midnight Scan Club dataset (MSC01 and MSC09). (B) Percentage of total cerebellar volume (y-axis) vs. percentage of total cerebral surface area (x-axis) represented by each functional network. Black line denotes the identity line (one-to-one ratio). Errors bars denote standard error of the mean across 10 individuals. Note the relative overrepresentation of the frontoparietal network in the cerebellum vs. cerebral cortex. Adapted from Marek et al. [10].

The most dominant networks present in the lateral cerebellum were the frontoparietal control network and the default mode network. The frontoparietal control network was overrepresented 2-fold in the cerebellum compared to the cortex (Figure 2B), occupying more cerebellar volume than any other network. This overrepresentation was present in every individual, however, the magnitude varied across individuals. Though speculative, we posit that the disproportionate expansion of the lateral cerebellum in humans supports the impressive repertoire of adaptive capabilities, given the adaptive control functionality ascribed to the frontoparietal network [40], and may track with individual differences in these abilities.

Our group has also shown that the default mode network contains subnetwork structure in the cerebellum [41]. Specifically, lateral default mode cortical subnetworks are represented in the lateral lobes of the cerebellum, whereas medial default mode cortical subnetworks are represented in the posterior cerebellum and vermis. In this study, the ability to detect these fine-grained subnetworks was afforded by the precision functional mapping approach.

In addition to describing the spatial arrangement of functional networks in the cerebellum, we described the propagation of BOLD signals between the cerebral cortex and cerebellum [12]. BOLD signals in the cerebellum lagged BOLD signals in the cerebral cortex by 100–400ms in a network-specific manner, with the frontoparietal and default mode networks exhibiting the longest lag. This pattern was consistent across every individual. Informed by previous studies in humans and rodents [42,43] studying the reciprocal association of infra-slow BOLD activity (0.01–0.10Hz) and faster oscillating delta activity (0.5–4.0Hz), we developed a model in which BOLD activity originating in the cortex temporally organizes higher frequency activity originating in the cerebellum, providing windows of opportunity for the cerebellum (sender) to send adaptive control signals to the cortex (receiver). Future electrophysiological studies are needed to directly test this prediction.

Other Brain Structures

In addition to the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum, precision functional mapping is being used to delineate subcortical organization of other structures, such as the amygdala and hippocampus. For example, this individual-level approach revealed functional heterogeneity within the amygdala beyond what had been shown in group-level studies [44]. Precision functional mapping can be extended to other understudied structures in the brain, such as the brainstem or, with advances in fMRI resolution, the subthalamic nucleus. Similar to every structure analyzed thus far, precision functional mapping will likely generate fascinating new insights into human brain functional organization that have the potential to more readily translate into clinical domains than traditional group-level findings.

Clinical Impact of Precision Functional Mapping in Subcortical Structures

The subcortex and the cerebellum have been implicated in many neurological and psychiatric disorders [38,45–49]. We have shown that these brain structures contain measurable individual specificity in their functional organization. Thus, for translational neuroscience to be successful, we must move towards reliable individual mapping of functional neuroanatomy. Then, in large sample sizes we can begin to relate individual functional “variants” to disordered phenotypes [50]. Here, we discuss one example of potential translation from basic science to neurological disorders using precision functional mapping: target sites for deep brain stimulation (DBS).

DBS is a surgical procedure in which electrodes are placed in the brain and subsequently stimulated for the purpose of treating a number of conditions, including essential tremor, Parkinson’s disease, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. DBS often targets subcortical structures, such as the thalamus, globus pallidus, and subthalamic nucleus. It is well known that some DBS target sites are more consistently effective than others. However, it is not clear why such inconsistencies exist. Since precision functional mapping can be used to generate a reliable mapping of individuals’ functional brain organization, these maps can be combined with DBS to show how stimulation of a given targeted functional network relates to clinical outcomes [51]. Ultimately, the goal is to identify individualized sites that best improve symptoms. For example, the DBS sites most commonly targeted for essential tremor fall into the thalamic motor integration zones that were discovered with precision functional mapping. Intriguingly, the convergence of networks in this zone was incredibly consistent across individuals, and DBS in this region is highly successful in treating essential tremor (>80% improvement in nearly all patients) [52]. Conversely, a DBS site commonly targeted for Parkinson’s Disease and dystonia in the globus pallidus internal, is much less successful and was shown to be much more individually variable in its functional organization compared to the motor integration zone. Perhaps higher success rates reflect the high anatomical consistency in the functional organization of a given target site across individuals. Thus, directly studying the relationships between subcortical integration zones defined within individuals and clinical DBS outcomes is an exciting avenue of future research with the potential to inform clinical care.

Future Developments

Critical future avenues of research are needed, including reproducible accounts of how individual differences in functional organization relate to individual differences in behavior and clinical outcomes. Additionally, depending on the research question, task-based fMRI may provide improved utility compared to rest, specifically for researchers or clinicians seeking to localize individual-specific functions, such as motor or language processes. A recent study was able to parcellate the cerebellum in individuals using a comprehensive battery of tasks during fMRI acquisition [53]. However, this battery was quite intensive, including 26 tasks and requiring 10 hours of prescan training. Therefore, when studying multiple functional domains, we contend that currently resting state fMRI may provide the most leverage for less time than a large set of tasks.

Clinically translating individual-specific RSFC may also be facilitated through continued development and improvements in MRI hardware and sequences, including the use of multi-echo sequences. Recently, it was shown that 10 minutes of multi-echo fMRI data achieved equivalent reliability as 30 minutes of single-echo fMRI data [54]. Additionally, development of specialized sequences tailored for subcortical structures will be key in clinical translation. The MSC data were acquired at 4mm resolution. However, future studies focused on subcortical structures will likely benefit from smaller voxel sizes. For example, in Greene et al. [11] we reproduced the existence of integrative functional zones in the caudate and thalamus using data acquired with 2.6mm voxels, providing further confidence that integration was not simply an artifact of large voxels.

Concluding Remarks

The evolving approach of deep brain phenotyping, namely precision functional mapping, has shown that functional network organization is individually-specific around a central tendency. This principle holds for every brain structure we have studied thus far, including the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cerebellum. Additionally, this approach enabled the discovery of several new organizational principles, including the existence of focally distinct integration zones in the subcortex and frontoparietal network expansion within the cerebellum. Though only a few years in, we are confident that the horizon is very bright for ultimately translating precision functional mapping approaches to clinical use.

Highlights.

Precision functional mapping enables reliable maps of individual brain networks

This method has been extended to characterize subcortical and cerebellar organization

Subcortex contains integration zones with variable consistency across individuals

Cerebellum contains overrepresentation of the frontoparietal network in all subjects

Precision functional mapping of these structures holds promise for clinical utility

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by NIH grants K99 MH121518 (S.M.) and R01 MH104592 (D.J.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Posner MI, Petersen SE: The attention system of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 1990, 13:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shulman GL, d’Avossa G, Tansy AP, Corbetta M: Two attentional processes in the parietal lobe. Cereb Cortex 2002, 12:1124–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann TO, Gordon EM, Adeyemo B, Snyder AZ, Joo SJ, Chen M-Y, Gilmore AW, McDermott KB, Nelson SM, Dosenbach NUF, et al. : Functional System and Areal Organization of a Highly Sampled Individual Human Brain. Neuron 2015, 87:657–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Zöllei L, Polimeni JR, et al. : The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 2011, 106:1125–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, Vogel AC, Laumann TO, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, et al. : Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 2011, 72:665–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marek S, Tervo-Clemmens B, Nielsen AN, Wheelock MD, Miller RL, Laumann TO, Earl E, Foran WW, Cordova M, Doyle O, et al. : Identifying reproducible individual differences in childhood functional brain networks: An ABCD study. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2019, 40:100706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Adeyemo B, Huckins JF, Kelley WM, Petersen SE: Generation and Evaluation of a Cortical Area Parcellation from Resting-State Correlations. Cerebral Cortex 2016, 26:288–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaefer A, Kong R, Thomas Yeo BT: Functional connectivity parcellation of the human brain. Machine Learning and Medical Imaging 2016, doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-804076-8.00001-3. [DOI]

- 9.**.Braga RM, Buckner RL: Parallel Interdigitated Distributed Networks within the Individual Estimated by Intrinsic Functional Connectivity. Neuron 2017, 95:457–471.e5.Robust single-subject data from 4 individuals described sub-networks of the default mode network throughout the cerebral cortex. Moreover, individual subjects showed measurable and robust deviations away from the central tendency described in group average studies.

- 10.**.Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Gilmore AW, Newbold DJ, Greene DJ, Berg JJ, Ortega M, Hoyt-Drazen C, Gratton C, Sun H, et al. : Precision Functional Mapping of Individual Human Brains. Neuron 2017, 95:791–807.e7.Marked the expansion of single-subject imaging to a cohort of 10 individuals, showing increased reliability of fMRI data, specifically resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC), with increasing data quantities. Functional network organization was characterized in each individual’s cerebral cortex, providing evidence that all functional networks show measurable deviation away from the group average.

- 11.**.Greene DJ, Marek S, Gordon EM, Siegel JS, Gratton C, Laumann TO, Gilmore AW, Berg JJ, Nguyen AL, Dierker D, et al. : Integrative and Network-Specific Connectivity of the Basal Ganglia and Thalamus Defined in Individuals. Neuron 2020, 105:742–758.e6.Details the functional network organization of the basal ganglia and thalamus in 10 individuals from the Midnight Scan Club dataset. Precision functional mapping revealed the existence of both segregated and integrated functional network representations. Three integration zones were consistent across individuals, including motor, visual attention, and cognitive integration zones. The motor integration zone was near the ventral intermediate nucleus of thalamus, a site for deep brain stimulation to treat essential tremor.

- 12.**.Marek S, Siegel JS, Gordon EM, Raut RV, Gratton C, Newbold DJ, Ortega M, Laumann TO, Adeyemo B, Miller DB, et al. : Spatial and Temporal Organization of the Individual Human Cerebellum. Neuron 2018, 100:977–993.e7.Details the functional network organization of the cerebellum in 10 individuals from the Midnight Scan Club dataset. Precision functional mapping revealed individual-specific functional network representations, disproportionate overrepresentation of the frontoparietal control network in the cerebellum, and systematic lag in BOLD activity relative to the cerebral cortex.

- 13.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL: Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 1986, 9:357–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander GE, Crutcher MD, DeLong MR: Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, “prefrontal” and “limbic” functions. Prog Brain Res 1990, 85:119–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Averbeck BB, Lehman J, Jacobson M, Haber SN: Estimates of projection overlap and zones of convergence within frontal-striatal circuits. J Neurosci 2014, 34:9497–9505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haber SN: The primate basal ganglia: parallel and integrative networks. J Chem Neuroanat 2003, 26:317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haber SN: Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2016, 18:7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostan AC, Strick PL: The basal ganglia and the cerebellum: nodes in an integrated network. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018, 19:338–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarbo K, Verstynen TD: Converging structural and functional connectivity of orbitofrontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and posterior parietal cortex in the human striatum. J Neurosci 2015, 35:3865–3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang K, Bertolero MA, Liu WB, D’Esposito M: The Human Thalamus Is an Integrative Hub for Functional Brain Networks. J Neurosci 2017, 37:5594–5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi EY, Tanimura Y, Vage PR, Yates EH, Haber SN: Convergence of prefrontal and parietal anatomical projections in a connectional hub in the striatum. NeuroImage 2017, 146:821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crittenden BM, Mitchell DJ, Duncan J: Task Encoding across the Multiple Demand Cortex Is Consistent with a Frontoparietal and Cingulo-Opercular Dual Networks Distinction. J Neurosci 2016, 36:6147–6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dosenbach NUF, Visscher KM, Palmer ED, Miezin FM, Wenger KK, Kang HC, Burgund ED, Grimes AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE: A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron 2006, 50:799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dosenbach NUF, Fair DA, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE: A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn Sci 2008, 12:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadaghiani S, D’Esposito M: Functional Characterization of the Cingulo-Opercular Network in the Maintenance of Tonic Alertness. Cereb Cortex 2015, 25:2763–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newbold DJ, Laumann TO, Hoyt CR, Hampton JM, Montez DF, Raut RV, Ortega M, Mitra A, Nielsen AN, Miller DB, et al. : Plasticity and Spontaneous Activity Pulses in Disused Human Brain Circuits. Neuron 2020, 107:580–589.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newbold DJ, Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Seider NA, Montez DF, Gross SJ, Zheng A, Nielsen AN, Hoyt CR, Hampton JM, et al. : Cingulo-Opercular Control Network Supports Disused Motor Circuits in Standby Mode. [date unknown], doi: 10.1101/2020.09.03.275479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Rinne P, Hassan M, Fernandes C, Han E, Hennessy E, Waldman A, Sharma P, Soto D, Leech R, Malhotra PA, et al. : Motor dexterity and strength depend upon integrity of the attention-control system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:E536–E545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen SE, Robinson DL, Keys W: Pulvinar nuclei of the behaving rhesus monkey: visual responses and their modulation. J Neurophysiol 1985, 54:867–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen SE, Robinson DL, Morris JD: Contributions of the pulvinar to visual spatial attention. Neuropsychologia 1987, 25:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saalmann YB, Pinsk MA, Wang L, Li X, Kastner S: The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science 2012, 337:753–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen BB, Korbo L, Pakkenberg B: A quantitative study of the human cerebellum with unbiased stereological techniques. J Comp Neurol 1992, 326:549–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sereno MI, Diedrichsen J, Tachrount M, Testa-Silva G, d’Arceuil H, De Zeeuw C: The human cerebellum has almost 80% of the surface area of the neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117:19538–19543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton RA, Venditti C: Rapid Evolution of the Cerebellum in Humans and Other Great Apes. Curr Biol 2017, 27:1249–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA: Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2009, 32:413–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dum RP, Strick PL: An unfolded map of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and its projections to the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 2003, 89:634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guell X, Gabrieli JDE, Schmahmann JD: Triple representation of language, working memory, social and emotion processing in the cerebellum: convergent evidence from task and seed-based resting-state fMRI analyses in a single large cohort. Neuroimage 2018, 172:437–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmahmann JD, Guell X, Stoodley CJ, Halko MA: The Theory and Neuroscience of Cerebellar Cognition. Annu Rev Neurosci 2019, 42:337–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.*.Xue A, Kong R, Yang Q, Eldaief MC, Angeli P, DiNicola LM, Braga RM, Buckner RL, Thomas Yeo BT: The Detailed Organization of the Human Cerebellum Estimated by Intrinsic Functional Connectivity Within the Individual. [date unknown], doi: 10.1101/2020.09.15.297911.Described cerebellar functional network organization in two highly-sampled individuals. Found triple representation of functional networks in the cerebellum, as well as a representation of the visual network in the vermis.

- 40.Marek S, Dosenbach NUF: The frontoparietal network: function, electrophysiology, and importance of individual precision mapping. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2018, 20:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Marek S, Raut RV, Gratton C, Newbold DJ, Greene DJ, Coalson RS, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, et al. : Default-mode network streams for coupling to language and control systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117:17308–17319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitra A, Snyder AZ, Hacker CD, Pahwa M, Tagliazucchi E, Laufs H, Leuthardt EC, Raichle ME: Human cortical-hippocampal dialogue in wake and slow-wave sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113:E6868–E6876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitra A, Kraft A, Wright P, Acland B, Snyder AZ, Rosenthal Z, Czerniewski L, Bauer A, Snyder L, Culver J, et al. : Spontaneous Infra-slow Brain Activity Has Unique Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Laminar Structure. Neuron 2018, 98:297–305.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.*.Sylvester CM, Yu Q, Srivastava AB, Marek S, Zheng A, Alexopoulos D, Smyser CD, Shimony JS, Ortega M, Dierker DL, et al. : Individual-specific functional connectivity of the amygdala: A substrate for precision psychiatry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117:3808–3818.Applied precision functional mapping to the amygdala, establishing amygdala subdivisions containing default mode and dorsal attention network representations, rather than a unitary default mode representation.

- 45.Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB: The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci 1989, 12:366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradshaw JL, Sheppard DM: The neurodevelopmental frontostriatal disorders: evolutionary adaptiveness and anomalous lateralization. Brain Lang 2000, 73:297–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liston C, Cohen MM, Teslovich T, Levenson D, Casey BJ: Atypical Prefrontal Connectivity in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Pathway to Disease or Pathological End Point? Biological Psychiatry 2011, 69:1168–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greene DJ, Williams AC Iii, Koller JM, Schlaggar BL, Black KJ, The TouretteAssociation of America Neuroimaging Consortium: Brain structure in pediatric Tourette syndrome. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22:972–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mink JW: The Basal Ganglia and involuntary movements: impaired inhibition of competing motor patterns. Arch Neurol 2003, 60:1365–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seitzman BA, Gratton C, Laumann TO, Gordon EM, Adeyemo B, Dworetsky A, Kraus BT, Gilmore AW, Berg JJ, Ortega M, et al. : Trait-like variants in human functional brain networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:22851–22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alhourani A, McDowell MM, Randazzo MJ, Wozny TA, Kondylis ED, Lipski WJ, Beck S, Karp JF, Ghuman AS, Richardson RM: Network effects of deep brain stimulation. J Neurophysiol 2015, 114:2105–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perlmutter JS, Mink JW: Deep brain stimulation. Annu Rev Neurosci 2006, 29:229–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.King M, Hernandez-Castillo CR, Poldrack RA, Ivry RB, Diedrichsen J: Functional boundaries in the human cerebellum revealed by a multi-domain task battery. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22:1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynch CJ, Power JD, Dubin M, Gunning F, & Liston C (2020). Rapid Precision Functional Mapping of Individuals using Multi-Echo fMRI. Poster 1253, presented at Organization for Human Brain Mapping. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]