Abstract

We evaluated the effectiveness of NORTH STAR, a community assessment, planning, and action framework to reduce the prevalence of several secretive adult problems (hazardous drinking, controlled prescription drug misuse, suicidality, and clinically significant intimate partner violence and child abuse [both emotional and physical]) as well as cumulative risk. One-third of U.S. Air Force (AF) bases worldwide were randomly assigned to NORTH STAR (n = 12) or an assessment-and-feedback-only condition (n = 12). Two AF-wide, cross-sectional, anonymous, web-based surveys were conducted of randomly-selected samples assessing risk/protective factors and outcomes. Process data regarding attitudes, context, and implementation factors were also collected from Community Action Team members. Analyzed at the level of individuals, NORTH STAR significantly reduced intimate partner emotional abuse, child physical abuse, and suicidality, at sites with supportive conditions for community prevention (i.e., moderation effects). Given its relatively low cost, use of empirically-supported light-touch interventions, and emphasis on sustainability with existing resources, NORTH STAR may be a useful framework for the prevention of a range of adult behavioral health problems that are difficult to impact.

Keywords: community, prevention, hazardous drinking, intimate partner violence, child abuse, suicide, military

Adults receiving treatment for behavioral health problems such as intimate partner violence, child abuse, substance abuse problems, and suicidality represent only a small fraction of those affected (e.g., Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Salzinger, 1998; Demyttenaere et al., 2004). These problems are stigmatized, and individuals frequently do not let others know of their difficulties, leading us to label such troubles as “secretive problems” (Heyman, Slep, & Nelson, 2011). Secretive problems are prevalent in military populations. In anonymous surveys of the Air Force (AF), about 35% of active duty members reported substance abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), child abuse, or suicidality at a clinical level, yet only 1 in 13 of those reporting a secretive problem indicated that someone in uniform was aware of it (Heyman et al., 2011). These problems also exist at sub-clinical, high-risk levels for a larger segment of the population (e.g., Lorber, Xu, Heyman, Slep, & Beauchaine, 2018). Given the breadth of need and the lack of voluntary revelation to either formal or informal help-networks, a prevention science approach to implementing effective, efficient interventions widely is needed (e.g., Damschroder et al., 2009).

One challenge when designing and implementing prevention strategies is the need to be efficient. It is difficult to engage target populations in prevention activities, so, ideally, interventions would be both effective and impact numerous outcomes simultaneously. It is unlikely, for example, that broad swaths of the population would be willing to participate in a series of curricula, each seeking to prevent a different adverse outcome. One approach, taken by Communities that Care (CTC; Hawkins & Catalano, 2002), is to target cross-cutting risk and protective factors (RPFs). CTC is not a specific prevention program. Rather, it is a framework targeting an interconnected net of youth problems. Community and school-based action planning teams are guided through conducting a needs assessment that assesses risk and protective factors, identifies priorities, and selects evidence-based prevention activities that they implement. With ongoing evaluation and refinement of plans and implementation strategies, CTC offers schools and communities a standardized framework for flexibly using evidence-based programs.

Research over the last few decades has made it clear that not only are secretive problems interconnected (e.g., Foran, Heyman, Slep, & USAF Family Advocacy Research Program, 2014; Lorber et al., 2018), but they also appear to share a variety of RPFs (e.g., depressive symptoms, social support) that appear in the separate literatures for each problem (e.g., Foran, Slep, & Heyman, 2012; Foran, Heyman, Slep, Snarr, & USAF. Family Advocacy Research Program, 2012). Thus, these RPFs may offer efficient intervention targets for integrated, community-level prevention. A community-based, public health approach focused on RPFs offers the advantage of not requiring high-risk individuals to be identified and referred to potentially stigmatized services. A risk-factor-focused approach can be more efficient by focusing on RPFs that have impacts on multiple secretive problems (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2012).

We developed NORTH STAR (New Orientation for Reducing Threats to Health from Secretive problems That Affect Readiness), a prevention planning and implementation system for adult problems in the AF, as a parallel to CTC (Hawkins & Catalano, 2002), which targets adolescent problems. Like CTC, NORTH STAR is a system rather than a program, stepping community prevention teams through implementing a local community assessment, using data to select RPFs with multiple impacts, implementing evidence-based interventions to affect the selected RPFs broadly, and evaluating their impact. This approach is compatible with a limited resource context, where efficiency and sustainability are critical, making use of light-touch interventions with broad reach to make community-level changes.

Although population trials of preventative interventions are uncommon, Prinz, Sanders, Shapiro, Whitaker, & Lutzker (2009) completed such a trial on the Triple P parenting program in South Carolina. Counties were randomized to treatment or control, and public records were used to conduct the evaluation. The intervention itself targets parenting at several levels of intensity that community members self-select. The goal is not solely individual-level change (from directly receiving the intervention), but rather population-level change. This requires that enough of the target population receive some dose of the intervention directly, or indirectly through social networks, for the overall rate of maltreatment to be lower in treated communities.

Although evaluating a program rather than a system, Prinz et al.’s trial shares several theoretical underpinnings and methodological characteristics with the current study. First, the theory behind the population-level intervention supposes that people can directly benefit from participation in an intervention, but may still be affected by an intervention in which they do not participate. Instead, if intervention penetration is sufficient, people will benefit indirectly. Although these interventions do not specify a mechanism through which this might occur, some possibilities include modeling of healthier behavior (e.g., Latkin & Knowlton, 2015), social contagion originating from those whose behavior was affected by the intervention (e.g., Perkins, Subramanian, & Christakis, 2015), or a shift in the social norms for healthy and unhealthy behaviors (e.g., Sheeran et al. 2016). Thus, the premise is that if an approach is effective at the population level, effects should be apparent in population parameters. Geographical areas are the units of randomization, and outcomes are tested with cross-sectional population parameters regardless of the degree to which the individuals captured directly participated in any interventions. This is arguably a high bar to hold a prevention approach to, for it assumes (a) specific component interventions will be effective when implemented in real-world settings under real-world conditions, and (b) efforts to disseminate interventions will be effective in generating sufficient participation rates that the impact will be detectable at a population level.

In addition, the NORTH STAR approach, as a system for community-based efforts, left the implementation of programs in the hands of the communities themselves (with support), which further necessitates that communities be effective in their implementation of dissemination efforts. Although the emerging field of implementation science has begun to research, systematically, how to best disseminate empirically-supported prevention approaches (e.g., McHugh & Barlow, 2010), this field is young enough that these real-world efforts are based more on experience and anecdote than science. When these implementation challenges are coupled with the logistic necessity of working with small numbers of geographic units, it becomes apparent why so few population trials for IPV, child abuse, substance problems, or suicidality have been conducted. That said, the need to develop effective community-based prevention approaches for these problems is clear.

Given the implementation challenges we anticipated, we expected that NORTH STAR’s effects would be moderated by AF base Community Action Teams’ attitudes, context, and the quality of their implementation plans (i.e., CAT process factors). In the implementation science literature, these factors are determinants that serve as barriers and facilitators of prevention effort impacts and thus can interact with prevention approaches to affect change (see Damschroder et al., 2009). Given that NORTH STAR is a system of planning, selecting, and implementing effective activities that organizes and directs the actions of already existing community teams, we reasoned that the system would be most effective when determinants were supporting effective action (e.g., poor CAT collaboration, high barriers to implementation, and poor community support). In contrast, when determinants align to undermine effective prevention, the AF’s systems would be less affected by the extra structure and tools within NORTH STAR.

Military services are ideal organizations within which to study community-based prevention. First, military installations are semipermeable systems that are both part of, and separate from, their surrounding communities making them well-suited for comprehensive, multi-problem, focused prevention. Second, the AF had already (a) committed to preventing all of the targeted problems and (b) created an infrastructure to coordinate prevention activities among relevant agencies. Third, the AF conducted a biennial Community Assessment (CA), comprising theory-derived, psychometrically-sound measures of individual, family, workplace, and community functioning that could serve as a data source regarding both RPFs and outcomes, reducing NORTH STAR’s financial and time burden and increasing disseminability.

The RCT included evaluations of both outcome and CAT process. We hypothesized that bases assigned to NORTH STAR, compared with those assigned to the control condition, would show reduced rates of suicidality, alcohol and drug problems, IPV, child abuse, and cumulative risk (from the outcome data). Furthermore, we reasoned that, because prevention teams’ action plans had to be approved by base leadership, improvements in problem prevalences would be more pronounced when installations had climates more supportive of prevention.

Method

Participants

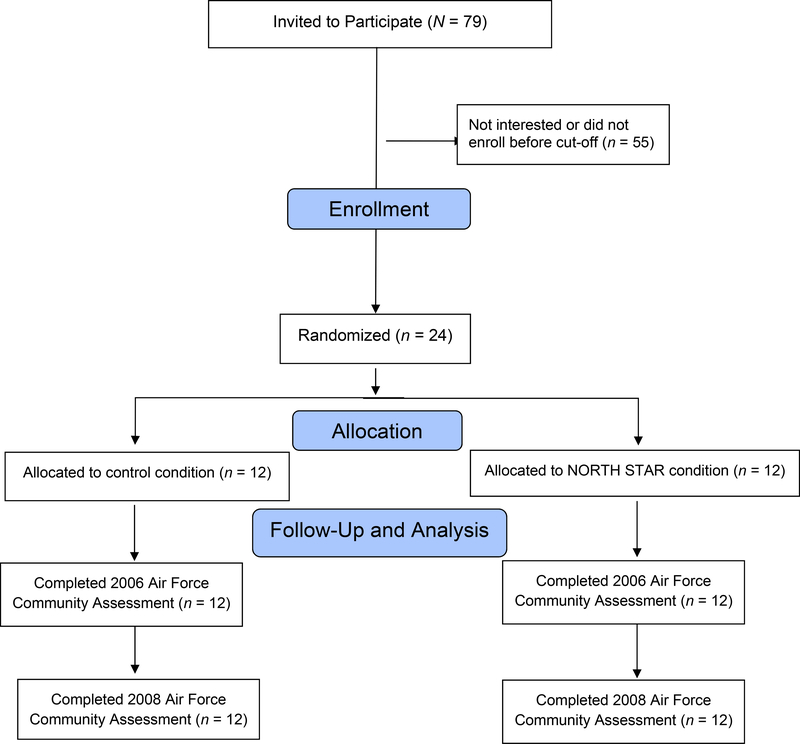

Twenty-four of the 79 AF installations with CATs (approximately 1/3 of all AF installations with teams) volunteered and enrolled in the study. To recruit sites, AF prevention leadership met with behavioral health points-of-contact from AF Major Commands, who then approached their installation-level counterparts. Those who were interested met with installation commanders to determine if the project was of interest. We sought installations from each Major Command; within Major Commands, volunteers were accepted until the study had the required number of installations. Commanders at each base signed a Memorandum of Agreement indicating their approval for participation. Data for study outcomes (i.e., secretive problems and RPFs) at the participating bases were from the 2006 and 2008 AF Community Assessment (CA). CAs were administered at all AF installations to representative samples of Active Duty (AD) members and to all spouses. Participation at the 24 bases was 16,020 AD members and 4,833 spouses from April – June 2006 and 16,998 AD members and 3,410 spouses from April – June 2008. AD response rates were excellent for long general population surveys with no payment (2006: 44.7%, 2008: 49.0%); spouse rates were considerably lower, perhaps in part because they were invited by mailed postcard (2006: 12.3%, 2008: 10.8%). Analyses of individual outcomes were restricted to the AD members (n = 33,018). Analyses of family outcomes were limited to individuals who were in a romantic relationship or had children; this sample included both AD members and spouses (n = 35,297). In cases in which multiple demographic variables indicated that both an AD member and his/her spouse participated, the spouse was selected for analysis. The individual outcome (AD-only) sample had the following characteristics: 73.8% male, M = 31.63 years-of-age (SD = 7.65), 67.1% married, 53.2% parents, and 21.5% officers. The family outcomes (AD member or spouse) sample had the following characteristics: 58.3% male; M = 32.61 years-of-age (SD = 7.65), 84.8% married, 64.5% parents, and 23.9% officers.

Members of the CATs (then known then in the AF as the “Integrated Delivery System”) at participating bases also participated. CATs were introduced in the late 1990s to plan and execute integrated, cross-problem efforts to address community needs. By AF regulations, each base was required to have a CAT, comprising representatives from agencies involved in health and wellness. CATs included representatives from Family Advocacy (IPV and child abuse); Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment; Health and Wellness Center; Airman and Family Readiness Center; Chapel; Wellness; and often the base comptroller’s office. Although CATs did not have budgets, they worked directly with base leadership and were required to use CA data to identify needs and create a biennial Community Action Plan (CAP). CAT members at all participating bases were invited to participate in the CAT process evaluation surveys; N = 205 participated (M per base = 8.91, SD = 5.04), ns = 205 (pre-action planning), 116 (post-action planning), and 136 (follow-up).

Procedure

Design.

We conducted an RCT, with outcomes assessed using repeated, cross-sectional surveys, randomly assigning the 24 bases to NORTH STAR versus control with a 1:1 allocation ratio, assigned in a single block using Microsoft Excel’s random number generator. Dr. Heyman conducted the randomization; bases were informed of assignment by Col. Linkh. Repeated cross-sectional surveys sample each participating community at multiple time points, but sample separate individuals each time. The outcomes, secretive problems, and cumulative risk were measured in independent samples of people within each base in 2006 and 2008. As described in Atienza and King (2002) and Murray et al. (2004), the repeated cross-sectional surveys within an RCT suits the goal of community-based interventions: to change health at the community level. Also, repeated cross-sectional surveys are unaffected by attrition.

Community assessments.

AD members and spouses anonymously completed the online CA in the springs of 2006 and 2008 (see Snarr, Heyman, & Slep, 2007). The CA included all study RPFs and outcomes, as well as other constructs that are not of present focus.

Experimental conditions.

Bases were randomly assigned to NORTH STAR (the intervention condition; n = 12) or enhanced feedback (the control condition; n = 12). An activities-as-usual control was not an option given the interest in NORTH STAR and the need for randomization. Demographics variables are reported by group in Table S1 and did not differ.

NORTH STAR.

NORTH STAR is a data-driven system for planning and evaluating the implementation of EBIs targeting RPFs at a community level. To accomplish this, we taught CATs to use data in an actionable way to select and implement evidence-based strategies that, over time, should improve the RPF profile of the targeted community. Sustainability was built in, in that the data were presented in an easy-to-understand feedback report that guided action planning steps. An online tool supported implementation planning, and ongoing coaching and support was provided. Although this trial consisted only of a single “round” of planning and implementation, the notion is that with successive rounds, CATs would learn the system and resources (i.e., feedback report, guidebook, and implementation and evaluation planning toolkit) and would be able, ultimately, to implement NORTH STAR without outside support. Following the 2006 CA, bases in the NORTH STAR condition received a 1.5-day on-site CAT training from the investigative team, who accompanied CAT-leaders to pre- and post-training briefings with base leadership. The training reviewed the results of the base’s feedback report and assisted the CAT in developing an action plan. The feedback report provided (a) base prevalences of secretive problems and (b) their relationships with cross-cutting, malleable RPFs (e.g., depressive symptoms, parenting satisfaction). The individual, family, workplace, and community RPFs were selected from the literature and based on the AF’s Community Readiness Consultant Model (Bowen, Martin, Liston, & Nelson, 2009). This model formed the basis of the CA and was developed through an iterative process of working groups with key stakeholders (e.g., leaders of AF health and wellness entities, research partners) to select RPFs at different levels of the social ecology that were (a) consistent with existing theory and literature and (b) viewed as important and actionable by the stakeholders. NORTH STAR’s feedback report identified interrelations among secretive problems and RPFs, to identify risky RPFs that had relations to multiple problems. Once RPFs were prioritized, the CAT turned to the NORTH STAR Guidebook (Slep & Heyman, 2006), comprising programs that were (a) empirically-supported to improve one or more RPF, (b) implementable on a large scale, and (c) available for implementation. The Guidebook was compiled via extensive literature searching, coupled with contacting developers directly to (a) identify programs that were effective and disseminable, but were not yet in the literature and (b) understand the disseminability of programs that were in the literature but not systematically disseminated.

CAT teams considered the strength of the effectiveness evidence of candidate programs, and fit with needs and available resources to create a final plan that included two to three RPFs targeted by up to two programs each. Once final interventions were identified, CATs completed a series of implementation planning activities, identifying the number and nature of target consumers, methods of delivery, responsible parties for each task, and timelines. This implementation plan was briefed to the base leadership for their approval after the meeting. Plans also included easy to use systems for tracking plan execution to provide the CAT with feedback about the quality of their implementation. These were designed with each CAT and tailored to their base and implementation strategy. We built an online toolkit that provided resources for tracking reach, fidelity, and proximal outcome indicators that included strategies, methods, and measures for each selected program. After the initial visit to each NORTH STAR base, continued implementation support was provided. This included regular implementation phone calls with designated CAT members, instrumental assistance (e.g., contacting intervention developers), quarterly conference calls with bases implementing a given program, a moderated listserv (so bases could share questions and ideas), and an electronic newsletter.

Selected EBIs are reported in Table S2 of the supplement. They targeted the following RPFs: depressive symptoms, personal and family coping, intimate and parent-child relationship satisfaction, and physical activity. One CAT also chose an additional problem-focused prevention program.

CAT participants in the intervention group were asked the extent to which the activities of their action plans had been fully implemented at the follow-up assessment, with answers using a 4-point response scale. Approximately 1/3 of CAT participants selected 1 (Not at all; 1.4%) or 2 (A little bit; 31%), with 49.3% selecting 3 (Somewhat), and 18.3% selecting 4 (A lot).

Control condition.

Control bases were sent the detailed feedback reports summarizing the results of the CA that was identical to that reviewed at the NORTH STAR bases. This included much more extensive analyses of RPFs than was typically provided to bases following the CA. However, no additional training or explanation of the report occurred. Rarely, a control CAT contacted the research team with questions about the report, and these were answered.

CAT process assessments.

Each participating CAT member completed self-report assessments. These assessments occurred on three occasions: pre-action planning (before briefings on 2006 CA results), post-action planning (after briefings on 2006 CA results and CAPs were to have been made), and follow-up (before the 2008 CA).

Measures

Secretive problems.

Each secretive problem was scored as 1 or 0 (problem present/absent) based on thresholds denoting clinical significance. Because of the dichotomous scoring, internal consistency is not reported. All outcomes were considered primary outcomes.

Hazardous drinking.

Hazardous drinking was measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Allen, Litten, Fertig, & Babor, 1997). The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure of alcohol dependence created by the World Health Organization. It has well-established sensitivity and specificity against clinical assessments (Reinert & Allen, 2002; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Per Rumpf, Hampke, Meyer, and John (2002), individuals who scored ≥ 8 were classified as above the cutoff for hazardous drinking.

Controlled prescription drug misuse.

Participants completed a checklist of commonly abused controlled prescription medications (e.g., amphetamines and codeine; Heyman, Slep, & Nelson, 2011). For each drug checked, the respondent was asked the frequency of use (a) when s/he did not have a prescription and (b) at a dosage higher than prescribed. Prescription drug misuse was scored as present based on any positive response.

Suicidality.

Suicidality (either serious ideation or attempts) during the previous year was assessed with four items from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey that have been used in nationally representative studies (Brener et al. 2002; Witte et al., 2008). Individuals were classified with suicidal ideation if they reported that they had (a) seriously considered attempting suicide rarely, sometimes, or frequently, (b) had thoughts of ending their lives sometimes or frequently, or (c) had planned a suicide. Suicidal behavior was indicated by a non-zero response to a single item reflecting the frequency of actual suicide attempts.

Clinically significant IPV and child abuse [emotional and physical].

The Family Maltreatment measure (Heyman, Snarr, Slep, Baucom, & Linkh, 2020) was used to measure maltreatment that matches Department of Defense criteria (which have been adopted by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition) for clinically significant (CS) IPV and child abuse — non-accidental acts that cause harm (e.g., injury, fear) or have a high potential for harm (e.g., burning, using a weapon, choking). This measure has demonstrated content, concurrent, convergent, and response process validity (Heyman et al., 2020). The Family Maltreatment measure has four modules: (1) physical IPV perpetration and victimization, (2) emotional IPV victimization, (3) physical child abuse perpetration, and (4) emotional child abuse perpetration. Each asks about (a) 12-month occurrence of acts: partner emotional aggression (9 items) and physical aggression (14 items) and child emotional aggression (9 items) and physical aggression (18 items); and (b) impacts of the acts (e.g., injury, fear). To meet the threshold of CS-IPV or CS-child abuse, individuals needed to report (a) one or more acts of aggression and (b) significant harm or high potential for harm. Physical CS-IPV perpetration and victimization were combined into a variable indicating physical CS-IPV in the household; child abuse perpetration was combined across children.

Cumulative risk.

We counted additive risk across 22 RPFs, following Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, and Baldwin (1993). All CA RPFs have adequate-to-strong internal consistency (see online supplement) and indications of construct validity in the current samples (see Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Snarr, Slep, Heyman, & Foran, 2011; Foran, Heyman, Slep, Snarr, & U. S. Air Force Family Advocacy Program, 2012). RPFs are grouped in four ecological levels: individual (economic stress, physical health, personal coping, spirituality/religiosity, depressive symptoms, and personal deployment preparedness), family (parent-child relationship satisfaction, intimate relationship satisfaction, family coping, career support from a significant other, and partner readiness for deployment), workplace (workgroup cohesion, workplace relationship satisfaction, and satisfaction with the AF), and community (community safety, satisfaction with community resources, community cohesion, support from neighbors, support from formal agencies, social support, community support for youth, and support from AF leadership). Each RPF was dichotomously scored; individuals who fell into the least adaptive ¼ of each variable’s distribution (i.e., the top 25% for risk factors; the bottom 25% for protective factors) received a 1; the remaining ¾ received a 0. The cumulative risk index was calculated by summing across these 22 dichotomous scores (range = 0 – 22).

CAT process.

Responses to four scales were combined to create composite measures of CAT process factors. The online supplement provides expanded descriptions and psychometrics for the scales: the (a) Prevention Programming and Implementation Questionnaire (PPIQ); (b) the Community Readiness Factors Questionnaire (CRFQ); (c) Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy Questionnaire (EOEQ); and (d) the Community Action Plan Questionnaire (CAPQ). Based on conceptual and empirical criteria (i.e., correlations ≥ .50 among the CAT process variables), we calculated four multi-scale composite scores by first standardizing and then averaging constituent subscales’ scores. Orientation toward empirical prevention comprised the PPIQ use of data, criteria influence, and risk and protective factors framework use subscales’ scores. Community support comprised the CRFQ community support for prevention, base leadership support for prevention, effective base leadership, and community/CAT resistance to change (reversed) subscales’ scores. CAP development comprised the CRFQ community action goal development, action plan development, and action plan specificity subscale’ scores. Barriers to implementation constituted the CRFQ barriers to implementation and EOEQ positive program-related expectancy subscales’ scores. The final set of eight baseline (i.e., measured at the pre-action planning assessment) CAT process variables used in our analyses included the above four composite variables and the PPIQ attitude toward community mental health data, CRFQ CAT collaboration, EOEQ present efficacy, and EOEQ program-related efficacy scores.

Change in CAT process factors was calculated for each of the eight above variables via linear slope scores across the pre-action planning, post-action planning, and follow-up assessments (coded 1, 2, and 3, respectively) at the base level for each variable. For composites, slopes were calculated for each constituent variable, then standardized and averaged. For the two variables not assessed at follow-up (both belonging to the orientation toward empirical prevention composite), slopes were equivalent to change scores.

Analytic Strategy

Hypotheses were tested with multilevel analysis with robust maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus (Muthén, & Muthén, 1998–2017); “type = TWOLEVEL RANDOM” in Mplus settings. Individual outcomes were analyzed in the AD sample (n = 33,018). CS-IPV was analyzed for those in the family sample with intimate partners (n = 34,314); likewise, CS-child abuse was analyzed for those in the family sample with children (n = 22,755). Multiple imputation estimated missing data, using IVEware (Raghunathan, Solenberger, & Van Hoewyk, 2002). For each sample, five datasets were imputed, analyzed, and results combined according to Rubin’s rules (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Data for both active duty members and spouses were weighted to their respective AF population level for rank (of the military member) and sex.

Baseline differences between groups.

In the AD and family datasets, each of 10 demographic variables were examined for Time 1 group differences that might confound intervention effects. This was accomplished via multilevel models that regressed each of these variables on group. The CAT process variables were compared in the CAT process data set via independent samples t-tests, with accompanying ds.

Main effects of the intervention on secretive problems and cumulative risk.

The intended analytic strategy was to model base level changes in secretive problems and cumulative risk as a function of group. However, although descriptively secretive problems seemed to show varying degrees of changes (Level 2), the degree of variability among the bases was not statistically significant for secretive problems or cumulative risk. Thus, we conducted multilevel analyses with intervention effects estimated at Level-1 (i.e., person). Each outcome was simultaneously regressed on time (2006 and 2008 cohorts treated as independent groups, given the repeated cross-sectional assessments), group, Time × Group, and five control variables (CAT collaboration, community action plan development, program-related efficacy, present efficacy, and barriers to implementation), all treated as Level-1 covariates. Dichotomous predictors were effects coded (+1 vs. −1); continuous predictors were grand mean centered. Level-2 variation in the outcomes was also allowed, as was a threshold/intercept. The Time × Group term (i.e., Does change over time in the secretive problem depend on group?) reflects the main effects of intervention, adjusted for covariates. We report the ICC for within-base nesting effects for cumulative risk only, as ICCs cannot be calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Sample syntax is included in the online supplement to this article.

Moderation of intervention effects by CAT process variables.

We evaluated whether intervention effects were moderated by (a) baseline levels of each of the eight CAT process variables, and (b) change in each of the CAT process variables. These effects were tested via multilevel models at Level 1 (Level-2 variation in the outcomes was also allowed), with each outcome regressed on time (2006 and 2008 cohorts treated as independent groups), group, moderator, Time × Group, Time × Moderator, Group × Moderator, Time × Group × Moderator, and five control variables. Continuous predictors were mean centered; dichotomous variables (time and group) were centered with effects coding (−1 and 1). Significant interactions were decomposed via simple slopes plotted at +/− 1 SDs on the moderator (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). To control for Type I error, Bonferroni corrections were employed with familywise alpha set to .05. The adjusted criterion p-value for the eight moderation tests per outcome for CAT process variables was .006 in both the CAT process baseline and change analyses.

Results

Baseline Differences Between Groups

None of the multilevel models found significant demographic differences between groups. As shown in Supplement Table S3, the largest group difference effect sizes (d = .11 and odds ratio [OR] = .84) also indicated differences were negligible. Among CAT process variables, only program-related efficacy significantly differed between groups (t = −2.07, p =.039). However, five of the ds > .30, and thus were selected as covariates in outcome analyses.

Main Effects of Intervention on Secretive Problems and Cumulative Risk

None of the Time × Group effects were significant (Tables S4–5); thus, the main effects hypotheses were not supported Within-base nesting effects were minimal (ICC = .01) for cumulative risk, the one outcome with a computable ICC; there was little evidence to suggest similarity among individuals due to shared membership in AF installations.

Moderation of Intervention Effects

Moderation by baseline CAT process variables.

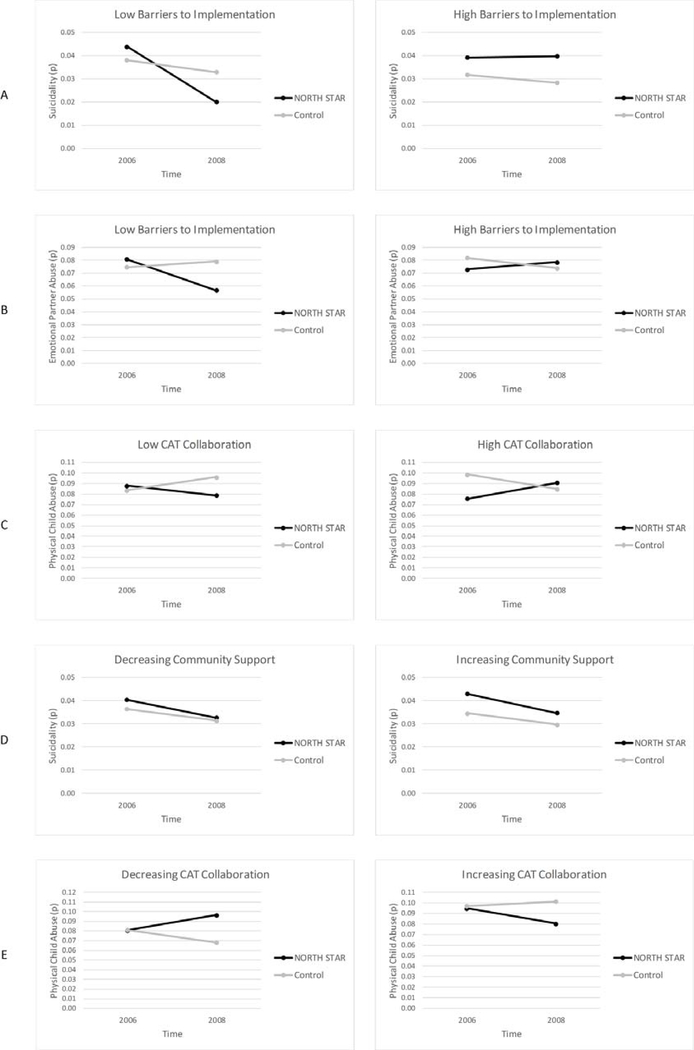

CAT process variables significantly moderated intervention effects for suicidality (Supplement Table S6), emotional CS-IPV (Supplement Table S7), and physical CS-child abuse (Supplement Table S8).

Suicidality.

The Time × Group × Barriers-to-Implementation interaction was significant (Figure 2, Panel A). When barriers to implementation were low, NORTH STAR participants exhibited a significant decrease in suicidality (simple slope (B) = −0.40, SE = 0.07, p < .001, 95% CI: −0.55, −0.26), whereas control participants did not exhibit reliable change (B = −0.07, SE = 0.05, p = .126, 95% CI: −0.17, 0.02). When barriers to implementation were high, neither NORTH STAR (B = 0.01, SE = 0.06, p = .919, 95% CI: −0.12, 0.13) nor control (B = −0.06, SE = 0.05, p = .234, 95% CI: −0.16, 0.04) participants exhibited reliable change in suicidality.

Figure 2.

Significant 3-way interactions.

Emotional CS-IPV.

The Time × Group × Barriers-to-Implementation interaction was significant for emotional CS-IPV (Figure 2, Panel B). When barriers to implementation were low, NORTH STAR participants exhibited a significant decrease in emotional CS-IPV (B = −0.19, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI: −0.28, −0.09), whereas control participants did not exhibit reliable change (B = 0.03, SE = 0.04, p = .404, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.10). When barriers to implementation were high, neither NORTH STAR (B = 0.04, SE = 0.04, p = .316, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.11) nor control (B = −0.05, SE = 0.08, p = .516, 95% CI: −0.22, 0.11) participants exhibited reliable change in emotional CS-IPV.

Physical CS-child abuse.

The Time × Group × CAT Collaboration interaction was significant (Figure 2, Panel C). Decomposition of this interaction indicated that none of the constituent simple slopes were significant. At high levels of CAT collaboration, the simple slope for NORTH STAR was positive (B = 0.12, SE = 0.08, p = .137, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.28) and the simple slope for control was negative (B = −0.06, SE = 0.04, p = .127, 95% CI: −0.14, 0.02). At low levels of CAT collaboration, the simple slope for NORTH STAR was negative (B = −0.08, SE = 0.05, p = .090, 95% CI: −0.18, 0.01) and the simple slope for control was positive (B = 0.06, SE = 0.05, p = .265, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.15).

Moderation by CAT process change variables.

CAT process change across time significantly moderated intervention effects for suicidality (Supplement Table S9) and physical CS-child abuse (Supplement Table S10).

Suicidality.

The Time × Group × Community Support Change interaction was significant (Figure 2, Panel D). With decreasing community support, NORTH STAR participants exhibited a significant decrease in suicidality (B = −0.17, SE = 0.04, p < .001, 95% CI: −0.25, −0.10), whereas control participants did not exhibit reliable change (B = −0.01, SE = 0.04, p = .855, 95% CI: −0.09, 0.08). With increasing community support, the pattern was reversed: control participants exhibited a significant decrease in suicidality (B = −0.15, SE = 0.04, p = .001, 95% CI: −0.23, −0.06), whereas NORTH STAR participants did not exhibit reliable change (B = −0.05, SE = 0.07, p = .447, 95% CI: −0.18, 0.08).

Physical CS-child abuse.

The Time × Group × CAT Collaboration Change interaction was significant (Figure 2, Panel E). With increasing CAT collaboration, NORTH STAR participants exhibited a significant decrease in physical CS-child abuse (B = −0.09, SE = 0.04, p = .035, 95% CI: −0.18, −0.01), whereas control participants did not exhibit reliable change (B = 0.02, SE = 0.02, p = .298, 95% CI: −0.02, 0.07). With decreasing CAT collaboration, neither control (B = −0.09, SE = 0.07, p = .176, 95% CI: −0.23, 0.04) nor NORTH STAR (B = 0.10, SE = 0.06, p = .117, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.22) participants exhibited statistically significant change in physical CS-child abuse.

Discussion

The impact of NORTH STAR, a prevention planning system for reducing rates of secretive problems, was tested in the US Air Force. We hypothesized that NORTH STAR would reduce rates of hazardous drinking, suicidality, CS-IPV, and CS-child abuse. However, no significant main effects emerged. We further hypothesized that NORTH STAR would be more effective when the climate for prevention was supportive. NORTH STAR significantly reduced emotional CS-IPV, physical CS-child abuse, and suicidality when the local environment for prevention was supportive, even if the environment became less supportive over time. There were no instances where NORTH STAR had iatrogenic effects, even when interactions with CAT process variables were examined. These results suggest that NORTH STAR is a promising approach to reducing hidden behavioral health problems such as suicide and family violence.

NORTH STAR would likely produce greater improvements if more consistent implementation could be achieved. One-third of the intervention bases did not implement any prevention strategies. The intent-to-treat analyses we conducted are appropriate, but provide a conservative estimate of the effects of the intervention under ideal conditions. It could be that working with entire installations as the unit of implementation was not optimal because the base population is diverse, and stakeholders on the prevention teams often had primary allegiances to their specific agencies and supervisors. A just-completed trial of NORTH STAR implemented action plans in military workgroups, and the unit commanders oversaw these efforts. On the one hand, these commanders had no expertise in prevention planning and had other pressing duties. On the other, their motivation to support the functioning of their members was high. It could be that a narrower focus with more invested implementers will result in stronger impacts.

It could also be that with repeated cycles of assessment and implementation, implementation would have grown successively stronger as CATs gained familiarity with the system and programs. Community-based interventions seem to take several years to take root to achieve full impact (e.g., Quinby et al., 2008).

NORTH STAR is innovative in several ways. First, it offers an integrated approach to behavioral health promotion by targeting RPFs shared among many outcomes. Second, within the context of a focal community, it can be implemented with relatively low costs. Third, it is a population-level prevention approach. Thus, it is a framework that complements traditional emotional or psychoeducational prevention formats and policy-based prevention initiatives, offering stakeholders a more comprehensive prevention strategy.

NORTH STAR — because it is a framework, not a specific set of programs — is inherently flexible. As evidence accumulates and prevention programs aimed at the included RPFs evolve, and innovations are made, the menu of prevention choices can be modified. In addition, if an RPF not targeted accumulates evidence that it is more powerful than one originally targeted, the framework can incorporate it. In this way, NORTH STAR is more sustainable than many fixed programs because it is flexible and adaptable to improvements in both the assessment and intervention components. Implementation science has not yet addressed how to optimally balance flexibility and fidelity in prevention systems to optimize sustained impact. This will be a critical area of inquiry as community-based prevention efforts mature.

This RCT had numerous limitations. The study was in the field a decade ago. Although we think it is unlikely that time, or the evolution of AF activities in the intervening years, affected the psychometrics of the measures or the results of the study, it is impossible to know that with certainty. Nevertheless, this is the only study of its kind, offering valuable insights into the potential of community-based, multipronged prevention systems. Additionally, the study did not have enough base-level variability in secretive problems to model treatment effects at the level of randomization. Measures were limited to self-report and all the biases inherent in that. Additionally, because the data were repeated cross-sectional, rather than longitudinal within individual, we were unable to model change within person. The implementation challenges within the NORTH STAR condition suggest that despite the emphasis placed on making the system easy to use and selecting easy-to-implement activities, taking population-level action is inherently challenging and requires significant support to take hold. This experience was likely exacerbated by the relatively brief two-year study period, as similar prevention systems take a minimum of two years for implementation to begin to affect outcomes (e.g., Quinby, et al., 2008). We expect that if installation CATs completed successive cycles of data collection, planning, and implementation, they would build their skills and infrastructure and would gradually need less support to implement their programming choices effectively. Testing this hypothesis would require a longer research period than was feasible in this study. Also, the impact of a framework is inherently dependent on the effectiveness of the empirically-supported interventions that are selected and implemented within it. When the effectiveness of available interventions is limited, it necessarily impacts the potential effectiveness of NORTH STAR. Finally, although one-third of all the AF installations worldwide participated in the trial, it is likely they are not fully representative of all installations. Participating installations were able to organize the actions necessary to volunteer for the study, for example. In addition, we did not have the resources necessary to execute the study at more than one-third of the bases in the AF simultaneously, and the intervention length was fixed by funding constraints and the timing of the CAs. Although additional approaches to gaining power were considered (e.g., randomizing timing of interventions within installation), this was not practical and cut against the design of NORTH STAR, which was to work within existing structures and real-world systems to increase ease of use and sustainability. The study has limited power at the level of the installation.

This study suggests several avenues for future research. First, this study highlights the importance of understanding the mechanisms driving uptake and implementation. Despite decisions to implement specific EBIs, and the availability of technical support, many bases did not implement their action plans. As implementation science grows, it will be important to understand mechanisms driving complete and efficient implementation in real-world contexts. Second, little is known about the mechanisms of change in population-based prevention studies such as this one. It is clear that there can be dynamics at different levels of the social ecology that can spread the reach of an individual receiving an intervention (or spread resistance to a particular program). Identifying mechanisms of “contagion” throughout the social milieu will help improve the impact of interventions seeking to achieve population-level change.

In summary, NORTH STAR has promise to complement existing prevention efforts that tend to be problem-specific (e.g., reducing hazardous drinking in junior enlisted AF members or preventing child abuse in at-risk parents). We did not observe significant main effects. Yet, in supportive AF environments, NORTH STAR appears to reduce clinically-significant problems without targeting them directly. To reduce secretive problems, an approach that targets shared RPFs instead of the outcomes themselves, might help improve health in ways that problem-specific programs cannot. Finally, NORTH STAR has the flexibility to incorporate advances and target emerging needs, boosting sustainability. Taken together, there is potential for NORTH STAR, and frameworks like it, to help promote empirically-supported interventions in large systems to decrease problems and improve health.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the NORTH STAR RCT

Table 1.

Summary of Results from Multilevel Models

| 95% CI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | B | SE | p | low | high |

| Intervention Main Effects a | |||||

| Hazardous drinking | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.866 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| Controlled prescription drug misuse | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.696 | −0.11 | 0.08 |

| Suicidality | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.543 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Cumulative risk | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.407 | −0.12 | 0.05 |

| Emotional CS-IPV | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.558 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| Physical CS-IPV | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.481 | −0.10 | 0.05 |

| Emotional CS-child abuse | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.339 | −0.12 | 0.04 |

| Physical CS-child abuse | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.884 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Dependent Variable | Moderatorb | |||||

| Suicidality | Barriers to implementation | 0.12 | 0.04 | .002 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Emotional CS-IPV | Barriers to implementation | 0.10 | 0.03 | .002 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| Physical CS-child abuse | CAT collaboration | 0.34 | 0.11 | .002 | 0.12 | 0.55 |

| Suicidality | Community support change | 0.08 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Physical CS-child abuse | CAT collaboration change | −0.40 | 0.11 | <.001 | −0.61 | −0.18 |

Note. Coefficients are for

Time × Group and

Significant moderated effects (Time × Group × Moderator) reported; full output reported in Tables S3–S9 of the online supplement.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported by the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH0610165) and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (K23DK115820). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Defense, U.S. Air Force, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent. Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants in the study.

Contributor Information

Amy M. Smith Slep, New York University.

Richard E. Heyman, New York University

Michael F. Lorber, New York University

Katherine J. W. Baucom, New York University

David J. Linkh, Ellsworth Air Force Base

References

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, & Babor T (1997). A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 21, 613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atienza AA, & King AC (2002). Community-based health intervention trials: An overview of methodological issues. Epidemiologic Reviews, 24, 72–79. doi: 10.1093/epirev/24.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL, Martin J, Liston BJ, & Nelson JP (2009). Building community capacity in the U.S. Air Force: The Community Readiness Consultant Model. In Roberts AL (Ed.) Social Workers’ Desk Reference (2nd ed., pp. 912–917). [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, & Ross JG (2002). Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 336–342. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00339-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, & Salzinger S (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22, 1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine J, ... & Kikkawa T (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA, 291, 2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Heyman RE, Slep AMS, Snarr JD, & Air US Force Family Advocacy Program. (2012). Hazardous alcohol use and intimate partner violence in the military: Understanding protective factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 471–483. doi: 10.1037/a0027688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Heyman RE, Slep AMS & U. S. Air Force Family Advocacy Program. (2014). Emotional abuse and its unique ecological correlates among military personnel and spouses. Psychology of Violence, 4, 128–142. doi: 10.1037/a003453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, Slep AMS, & Heyman RE (2011). Hazardous alcohol use among active duty Air Force personnel: Identifying unique risk and protective factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25, 28–40. doi: 10.1037/a0020748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, & Catalano RF (2002). Investing in your community’s youth: An introduction to the Communities That Care system. South Deerfield, MA: Channing Bete Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Oesterle S, Brown EC, Monahan KC, Abbott RD, Arthur MW, & Catalano RF (2012). Sustained decreases in risk exposure and youth problem behaviors after base of the Communities That Care prevention system in a randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166, 141–148. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Slep AMS, & Nelson JP (2011). Empirically guided community intervention for partner abuse, child maltreatment, suicidality, and substance misuse In MacDermid Wadsworth S & Riggs D (Eds.), Risk and Resilience in U.S. Military Families (pp. 85–110). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Snarr JD, Slep AMS, Baucom KJW, & Linkh DJ (2020). Self-reporting DSM–5/ICD-11 clinically significant intimate partner violence and child abuse: Convergent and response process validity. Journal of Family Psychology, 34, 101–111. doi: 10.1037/fam0000560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell DC (2012). Statistical methods for psychology (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Jo B, & Muthén BO (2001). Modeling of intervention effects with noncompliance: A latent variable approach for randomized trials In Marcoulides GA & Schumacker RE (Eds.), New developments and techniques in Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 57–87). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Snarr JD, Slep AMS, Heyman RE, & Foran HM (2011). Risk for suicidal ideation in the U.S. Air Force: An ecological perspective. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 600–612. doi: 10.1037/a0024631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, & Knowlton AR (2015). Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: A critical review. Behavioral Medicine, 41, 90–97. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2015.1034645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, Xu S, Heyman RE, Slep AMS, & Beauchaine TP (2018). Patterns of psychological health problems and family maltreatment among United States Air Force members. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1258–1271. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, & Barlow DH (2010). The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist, 65, 73–84. doi: 10.1037/a0018121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM, Varnell SP, & Blitstein JL (2004). Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: A review of recent methodological developments. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 423–432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins JM, Subramanian SV, & Christakis NA (2015). Social networks and health: A systematic review of sociocentric network studies in low- and middle-income countries. Social Science and Medicine, 125, 60–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Sanders MR, Shapiro CJ, Whitaker DJ, & Lutzker JR (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P System Population Trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinby RK, Hanson K, Brooke‐Weiss B, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, & Fagan AA (2008). Installing the Communities That Care prevention system: Implementation progress and fidelity in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 313–332. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, & Van Hoewyk J (2002). IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software User Guide. Ann Arbor, MI: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, & Allen JP (2002). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26, 272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02534.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf H, Hampke U, Meyer C, & John U (2002). Screening for alcohol use disorders and at-risk drinking in the general population: Psychometric performance of three questionnaires. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37, 261–268. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, & Baldwin C (1993). Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development, 64, 80–97. doi: 10.2307/1131438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Turner KM, & Markie-Dadds C (2002). The development and dissemination of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A multilevel, evidence-based system of parenting and family support. Prevention Science, 3, 173–189. doi: 10.1023/A:1019942516231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Maki A, Montanaro E, Avishai-Yitshak A, Bryan A, …Rothman AJ (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35, 1178–1188. doi: 10.1037/hea0000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS & Heyman RE (Eds.). (2006). Enhancing the Integrated Delivery System: A Guidebook to Activities That Work, Third Edition. New York, NY: Family Translational Research Group, New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Snarr JD, Heyman RE, & Slep AMS (2007). The 2006 Air Force behavioral health problem review: Assessing the prevalence of force health challenges. Stony Brook, NY: Stony Brook University. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. (2006). Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Retrieved from pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032006/hhinc/new01_001.htm [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK, Merrill KA, Stellrecht NE, Bernert RA, Hollar DL, Schatschneider C, & Joiner TE (2008). “Impulsive” youth suicide attempters are not necessarily all that impulsive. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.