Abstract

Ethiopia’s expansion of primary health care over the past 15 years has been hailed as a model in sub-Saharan Africa. A leader closely associated with the programme, Tedros Adhanom Gebreyesus, is now Director-General of the World Health Organization, and the global movement for expansion of primary health care often cites Ethiopia as a model. Starting in 2004, over 30 000 Health Extension Workers were trained and deployed in Ethiopia and over 2500 health centres and 15 000 village-level health posts were constructed. Ethiopia’s reforms are widely attributed to strong leadership and ‘political will’, but underlying factors that enabled adoption of these policies and implementation at scale are rarely analysed. This article uses a political economy lens to identify factors that enabled Ethiopia to surmount the challenges that have caused the failure of similar primary health programmes in other developing countries. The decision to focus on primary health care was rooted in the ruling party’s political strategy of prioritizing rural interests, which had enabled them to govern territory successfully as an insurgency. This wartime rural governance strategy included a primary healthcare programme, providing a model for the later national programme. After taking power, the ruling party created a centralized coalition of regional parties and prioritized extending state and party structures into rural areas. After a party split in 2001, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi consolidated power and implemented a ‘developmental state’ strategy. In the health sector, this included appointment of a series of dynamic Ministers of Health and the mobilization of significant resources for primary health care from donors. The ruling party’s ideology also emphasized mass participation in development activities, which became a central feature of health programmes. Attempts to translate this model to different circumstances should consider the distinctive features of the Ethiopian case, including both the benefits and costs of these strategies.

Keywords: Primary health care, political economy, Ethiopia

Key Messages

This study examines Ethiopia’s primary healthcare reforms. While primary care programmes have failed in many low-income countries, Ethiopia has scaled up primary care service delivery by building and equipping health centres and health posts, and through implementation of a large-scale community health worker programme.

Many studies of these reforms highlight ‘political will’ as the central factor. However, in the existing literature it remains unclear how this political will enabled Ethiopia to overcome the barriers to implementation of primary healthcare programmes at scale that have hindered progress in other countries.

This article uses case study methods to identify historical and political factors that contributed to the decisions of political leaders to prioritize primary health care. It also identifies institutional changes which enabled implementation at scale.

The decision to emphasize primary health care was rooted in the ruling party’s political strategy of prioritizing rural interests, which had previously enabled them to govern territory successfully as an insurgency. This wartime rural governance strategy included a primary healthcare programme featuring community health workers, providing a model for the later national programme. After taking power nationally, the ruling party also prioritized extending state and party structures into rural areas, enabling service delivery in these areas. After a split in the ruling party in 2001, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi consolidated power and pursued his developmental state ideology, including through appointment of a series of highly competent, technocratic Ministers of Health and mobilization of significant resources from donors. The ruling party’s ideology also emphasized mass popular mobilization, which became a feature of primary health programmes. This strategy of mass mobilizationhas become more controversial during Ethiopia's ongoing period of political transition.

“Let the peasants never be disaffected. Once they are disaffected, it will be the end of the world. But whatever happens, with the support of the peasantry, we may stagger, but we would surely make it.” (former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, quoted in Markakis (2011, pp. 248–9)).

"Even within Ethiopia, many similar projects had been initiated some years before. The reason for their lack of success, I think, was the lack of political commitment or political will … The government truly believed that primary health care, including a Health Extension Program focused on preventive care, should be the centrepiece of the health system. That is why it succeeded." (former Minister of Health, current WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Gebreyesus).1

Introduction

Ethiopia’s expansion of primary health care over the past 15 years has been hailed as a model in sub-Saharan Africa. Since 2004, >30 000 Health Extension Workers (HEWs) have been hired and deployed and >2800 health centres and over 15 000 village-level health posts were constructed. Ethiopia has seen sharp increases in access to basic services, although from a low base. For example, just 5% of deliveries took place in health facilities (Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), ORC Macro, 2001), but this increased almost 10-fold to 48% by 2019 (Ethiopia Public Health Institute, Federal Ministry of Health, ICF, 2019). Based on these achievements, Ethiopia has been described as a present-day successor to earlier primary healthcare success stories such as Sri Lanka, Kerala (India), Costa Rica and China (Balabanova et al., 2013). In 2016, the then-Minister of Health stated that 99% of Ethiopians now have access to primary health care (PHC) (Admasu, 2016). Momentum has built for the extension of this model to other countries, especially across sub-Saharan Africa.

Replicating Ethiopia’s model in other developing countries requires understanding it. yet the origins of this programme and the conditions that enabled this expansion of primary care services are not widely studied (Ostebo et al., 2017). This study uses a politically informed approach to health system analysis to address this question, by analysing Ethiopia’s PHC reforms in the context of the historical and political science literature on Ethiopian politics, political economy and health system development (Young, 1997; Kloos, 1998; Barnabas and Zwi, 1997; Lavers, 2019; International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019; Berhe, 2020a), and by comparing Ethiopia’s experience to the retrospective literature on global experiences with PHC programmes in developing countries (World Health Organization, 2008; McGuire, 2010; Glassman et al., 2018; Packard, 2016; Rifkin, 2018).

Globally, there are major evidence gaps regarding the conditions under which leaders choose to invest in structural, pro-poor health system reforms, such as broad-based expansion of primary health care. While there is a large political economy literature on the political preconditions for the emergence of a ‘developmental state’ focused on industrialization and economic growth, there is limited comparable theory and evidence on the requirements for a health-focused developmental state.2 However on primary care specifically, there is retrospective literature examining the failure of the global PHC programmes following the 1978 Alma Ata Conference. This literature suggests that political, institutional, financial and ideological barriers have hindered PHC programmes in developing countries. First, in many countries, health budgets have been spent predominantly on secondary and tertiary curative care in urban areas, rather than on primary care (World Health Organization, 2008). This is largely because political, economic, and even medical elites prefer this focus on curative services in urban facilities (Packard, 2016). Second, new PHC programmes require significant investment, but poor countries are highly budget constrained, even as new technologies and treatments emerge to further strain resources (Glassman et al., 2018). Donors have not typically emphasized or consistently funded primary health care, often preferring to emphasize verticalized, disease-specific programmes, or else capital investments (such as new clinic construction), technical assistance, or drug and commodity purchases, rather than support for recurrent costs such as community health worker salaries. As a result, even when large-scale PHC programmes have been attempted, many have broken down due to gaps in recurrent financing. Third, deployment of PHC-focused health workers and services requires significant implementation capacity, and community health worker programmes have also often decayed due to limited state capacity for management, oversight, and supervision of the large workforce that is required (Perry et al., 2014). Finally, particularly in the post-Alma Ata era, global ideological currents have not been hospitable to primary health care. For example, community health worker programmes represent a large expansion of the public sector work force, which fell out of fashion globally shortly after the 1980s (Rifkin, 2018). For others, these programmes are associated with a model of low-quality, basic care by low-skilled providers from which countries seek to graduate.

Yet while these structural factors are considered crucial in the retrospective literature on PHC in developing countries, they have been relatively neglected in explanations of the Ethiopian primary healthcare expansion. Most analyses of the Ethiopian case highlight ‘political will’ as the central variable, yet as is common in global health research (Fox et al., 2015), they do not analyse the concept of political will in detail, treating it as an exogenous factor or ‘black box’ concept, which cannot be further analysed. Some analyses focus on the personal characteristics of senior leaders such as former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and former Minister of Health Tedros Adhanom Gebreyesus (Minister of Health from 2005 to 2012) (Donnelly, 2011; Balabanova et al., 2013). While this analysis also finds that these individuals were deeply influential, it also seeks to understand the strategies and mechanisms by which these individuals and other senior leaders addressed the structural challenges to PHC implementation that have prevented progress in other settings. The specific choices that leaders make regarding provision of basic health services are driven by their ideas, values and political skill but are also shaped by the political constraints and opportunities that they face and are also mediated by the political institutions that structure political action. This article analyses the intersection of structural determinants and individual agency, highlighting aspects of Ethiopia’s historical and political development over the past generation that spurred leaders to make major investments in PHC, as well as the ideas and institutional choices and innovations which enabled implementation. In the discussion section, the limitations of this model and the implications for other countries seeking to emulate Ethiopia’s experience are also considered.

Methods

This article relies primarily on case study methodologies as used in political science and related fields (Gerring, 2004). Case studies of this type do not seek to test hypotheses or estimate causal relationships statistically, but rather to provide ‘thick description’ of phenomena in question, identify mechanisms of action through close observation of causal processes and generate hypotheses for further exploration. The goal of this approach is to provide specific insights from the Ethiopian case, which can complement findings from cross-country and within-country quantitative research designs on the same topic (Willis, 2014). In this framework, Ethiopia is considered a deviant case (Gerring, 2008), in that its implementation of primary health care has been unusual relative to other low-income countries over the period in question. It is also a theory-motivated case study: Ethiopia’s primary healthcare policies are analysed with reference to a set of specific barriers to PHC expansion, which are synthesized from historical and analytical accounts of Packard (2016), McGuire (2010), Perry et al., (2014), World Health Organization (2008) and Rifkin (2018). The obstacles to successful large-scale primary health programmes described in these accounts are synthesized by the author. Based on this synthesis, I categorize these challenges as distributional, implementation capacity-related, financial and ideological. How Ethiopian policymakers addressed each barrier to PHC programme expansion is analysed with reference to Ethiopia’s political and health system history. In addition, data from Demographic and Health Surveys, National Health Accounts, and international governance metrics such as the World Governance Indicators are analysed to place Ethiopia’s experience in comparative context and to triangulate against conclusions drawn from analysis of the secondary literature. Data are presented from other sub-Saharan African countries of comparable size to Ethiopia (Nigeria, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Kenya).3

Results

Ethiopia’s health system first emerged as Haile Selassie’s imperial regime (1930–74) created Ethiopia’s modern national institutions, including the Ministry of Public Health, established in 1947, referral hospitals and medical and health universities such as Addis Ababa University medical school and Gonder Public Health College (1952) (International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019, pp. 25–6). These early health structures were mostly in urban centres and were focused on curative care (Kloos, 1998, p. 509) and, as a result, reached relatively few Ethiopians. After the 1974 revolution that overthrew the imperial regime, the avowedly Marxist Derg regime had ambitious plans for primary health care, including a community health worker programme, but implementation of these plans was undermined by the Derg’s harshly repressive tactics and disproportionate military spending (Kloos, 1998 ). As a result, when the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) overthrew the Derg and took power in 1991, health services were dramatically underprovided in Ethiopia, even by regional standards. Health was not the immediate priority for the new regime, which first focused on creating a governing coalition incorporating ethnic parties from across Ethiopia (the Ethiopia People's Revolutionary Democratic Front, EPRDF), developing a new constitution and reorganizing the federal structure of the country. Despite the lack of major health programmes at this point, important initial steps in the first decade of EPRDF rule included the first National Health Policy in 1993 and the first Health Sector Strategic Plan in 1997. Despite this initial progress during the first decade of the EPRDF regime, at the time of the first Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in 2000, just 5% of deliveries took place in health facilities, compared to 44% in Tanzania (1999), 37% in Nigeria (1999), and 40.1% in Kenya (2003), and just 14.3% of children aged 12–23 months were fully vaccinated, compared to 68% (Tanzania), 51.8% (Kenya) and 16.8% (Nigeria). In the World Health Organization's (2000) World Health Report, Ethiopia’s health system was ranked 180 out of 189 in the world.

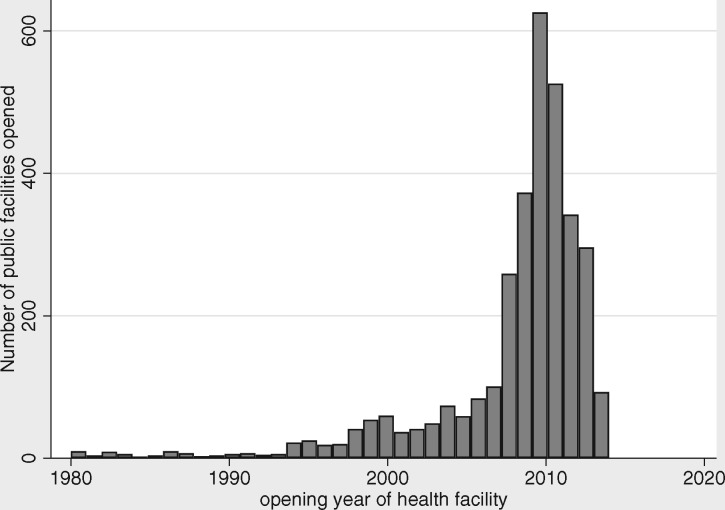

Ethiopia began its national expansion of primary health services in the second decade of the EPRDF regime, starting circa 2003. The most well-known component of this was the Health Extension Program (HEP), in which over 42 000 HEWs were trained to deliver basic primary care (Assefa et al., 2019). This health worker programme was implemented together with large-scale construction of primary hospitals and health centres and health posts to house HEWs. In addition, the Ministry bolstered the higher-level health workforce (doctors, health officers and midwives); including by creating a cadre of junior clinical staff trained specifically for rural service and then the broader ‘flooding’ policy, i.e. a policy to ensure adequate public sector workforce by flooding the market with clinical staff. For the HEW programme, two female secondary graduates, given 1 year pre-service training, were deployed to each newly constructed health post to serve a kebele (∼5000 people). The programme was launched in 2003 in agrarian areas and adapted in following years to pastoralist and then urban areas. Care was largely preventive, with 4 major areas of activity (family health, disease prevention and control, hygiene and environment and health education and communication) and 16 service packages. An important part of each HEW’s responsibility was to train ‘model families’ in each kebele who would demonstrate good health behaviour to their communities. After 2010–11, this aspect of the programme was expanded into the ‘Women’s Development Army’, in which this structure was massively extended, such that a model household was identified for every five households (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Government health facility openings in Ethiopia by year (source: National Health Facility Census 2014)

Over this period of primary healthcare expansion, Ethiopia has seen important improvements in key health system access measures: for example, the percentage of women who received antenatal care by a skilled provider increased from 27% in 2000 to 74% in 2019, while facility delivery increased from 5% to 48% over the same period. The percentage of children receiving all basic vaccinations ranged from 14% in 2000 to 43% in 2019. These absolute values as of 2019 were not out of line with other comparator countries, but the rate of change was relatively rapid; for example as Table 1 shows, Nigeria achieved a 6 percentage point increase in facility births over 15 years, while the same indicator in Tanzania increased by 19 percentage points over 17 years, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo it increased 11 percentage points over a 12-year period. Ethiopia’s annual increase in this outcome was roughly twice as fast as these comparator countries, although from a very low base.

Table 1.

Facility deliveries births over time, Ethiopia and comparator countries

| Country | Start year | Percentage of deliveries in health facility | End year | Total change | Change | Per year change (percentage points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | 2000 | 5 | 2019 | 48 | 43 | 2.3 |

| Nigeria | 2003 | 33 | 2018 | 39 | 6 | 0.5 |

| Tanzania | 1999 | 44 | 2016 | 63 | 19 | 1.1 |

| DRC | 2007 | 70 | 2018 | 82 | 12 | 1.0 |

| Kenya | 1993 | 44 | 2014 | 61 | 17 | 0.8 |

Source: Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) reports, various years.

How did Ethiopian policymakers address the challenges to primary care that stymied many other countries? In the section, drawing the secondary literature and data analysis conducted in 2019–20, the four barriers synthesized from the secondary literature on primary care (distributional politics, state capacity for implementation, financing and ideology) are addressed in turn.

Structural challenges: distributional politics

Primary healthcare programmes in developing countries require directing scarce resources to poor rural areas. This is often resisted by political and economic elites, the middle classes and the medical professions, especially when rural citizens are already politically and economically marginalized. Underinvestment in primary care had characterized Ethiopian health budgets in earlier periods: Kloos (1998) reports that circa 1972, 92% of health expenditures was on hospitals.

The EPRDF regime, like the imperial and Derg regimes before it, was undemocratic, which could provide some insulation from the pressures to channel resources to urban areas that more open regimes might face. However, many autocratic regimes use their insulation from popular pressure to favour elite, urban interests. The EPRDF regime did the opposite, shifting resources to rural areas not just in health but across multiple sectors. To understand why, it is necessary to analyse the political and ideological basis of the EPRDF regime and its historic origins. Political settlements that tax rural production to favour urban residents have been common in sub-Saharan Africa in the post-independence era (Bates, 1981), and strong incentives for political leaders to extend the reach of the state to remote rural areas have been limited (Herbst, 2000) and at times resisted by rural populations (Hyden, 1980). Ethiopia under the EPRDF sought the opposite strategy, investing in rural priorities such as agriculture, safety nets and rural services (De Waal, 2013; Tadesse, 2015; Lavers 2019; Clapham, 2017) while limiting investment in urban areas. This strategy was rooted in the regime’s origins in the TPLF's rural insurgency, which grew from a handful of fighters in a remote region in the late 1970s to ultimately defeating the Derg and taking over the national government in 1991. As a small guerilla force, the TPLF needed popular support from peasants in heavily rural Tigray to survive. Multiple accounts of the TPLF experience from both participants and academic analysts stress that this focus on peasant well-being was what allowed the TPLF to defeat other local insurgent groups, and ultimately to defeat the much larger military force of the Derg regime (Young, 1997; Berhe, 2020a). The TPLF refined this strategy over the course of their 17 years fighting to control territory in Tigray, focusing their activities during wartime on land reform, rural administration and security, popular participation and political education and mobilization.

This political and governance strategy had a well-developed health component. Barnabas and Zwi (1997 ) describe how over the course of the long guerilla war in Tigray (1975–91) the TPLF developed progressively more complex health strategies over time in the territory they controlled. Health programmes started with rudimentary first aid and treatment for combat injuries but gradually shifted to well-designed public health programmes including a community health worker programme to provide basic care, a strong emphasis on prevention (rather than curative medicine) and emphasis on community involvement and local resource mobilization. These health programmes were an important part of their strategy to govern the areas that they controlled and win the support of the rural poor. These wartime community health experiences were a key reference point for the TPLF leaders when they gained control of the national health system (Berhe, 2020b).

When the EPRDF took power nationally in 1991, they needed to legitimize their power nationally, given that they represented an ethnic minority from a remote part of Ethiopia. The immediate needs in the early 1990s were post-conflict reconstruction and the consolidation of a national political settlement. Focus and budget were next diverted by the 1998–2000 war with Eritrea. After the war, there was a deep split within the EPRDF. Prime Minister Meles Zenawi emerged from the split with consolidated power. Prime Minister Meles increased his personal authority within the regime and made his theory of the developmental state national policy (Clapham, 2018; Berhe, 2020a). The regime invested heavily in their ‘Agricultural Development-led Industrialization’ strategy, rural roads, electricity, the ‘Productive Safety Net Program’, and other programmes to target rural dwellers. Major investments in rural health care formed an important component of this strategy. By 2016/17, 44% of government recurrent health expenditure targeted the largely rural health posts and health centres, compared to 24% for public hospitals (Federal Ministry of Health, 2019). These policy choices in turn were rooted in earlier experiences: As former senior TPLF and EPRDF official Mulugeta Gebrehiwot Berhe has argued, ‘the initial model of governance of the TPLF aligned with the needs and knowledge of the rural poor was the beginning of its later pro-poor approach of governance that transcended the liberation war and shaped its policies of its transition into government’ (Berhe, 2020a).

Structural challenges: state capacity

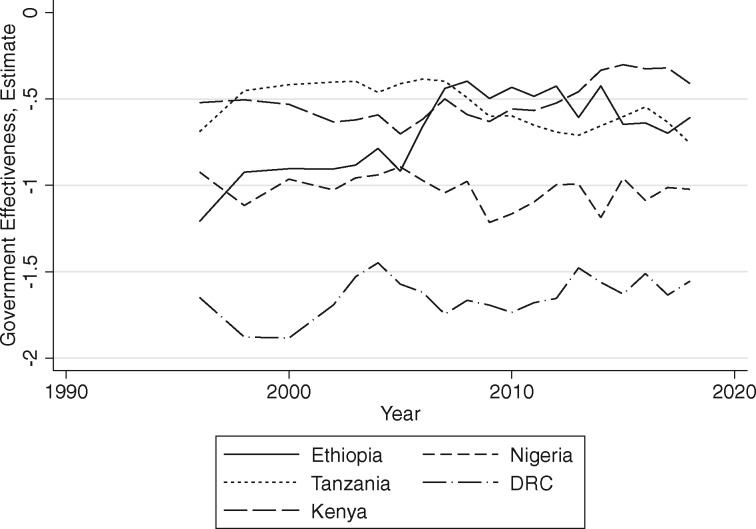

Even if distributional politics poses no obstacle to shifting health resources to primary care, a second major challenge is building the capacity of the state to deliver services in rural areas. Key elements of state capacity include the ability to extract taxation, coordinate the activities of multiple social groups and elicit compliance from both citizens and front-line agents of the state (Berwick and Christia, 2018). With respect to delivery of primary health, the state must mobilize resources and then hire, train, deploy, motivate and monitor a large front-line workforce conducting complex tasks in geographically dispersed settings. These are what Andrews et al. (2017) refer to as high transaction intensity, high discretion activities, which require relatively high levels of state capacity. Circa 2000, Ethiopia was not known for high levels of state capacity according to international metrics: according to the World Bank’s Government Effectiveness Indicator, Ethiopia’s was ranked 155 out of 186 countries. This indicator improved sharply in the mid-2000s, as Ethiopia shifted discontinuously from an estimated state capacity equal to Nigeria, to capacity roughly equal to Tanzania (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Government Effectiveness Estimates, Ethiopia and comparator countries (source: World Governance Indicators)

Historical origins

Despite Ethiopia’s low governance ratings as of 2000, the country benefitted from a unique heritage of ‘stateness’ due to the continuous existence of a centralized state, which had originally been centred in Axum in northern Ethiopia. From its origins in northern Ethiopia, this state gradually extended its control over much of the central highlands and had reached its current borders by end of the 19th century. The implementation capacity of this early state was limited by its feudal organization (Markakis, 2011), but it generated enough centralized military power to repulse Italian attempts to colonize Ethiopia in 1896. Unlike the rest of the continent, therefore, Ethiopia did not have its indigenous political development and state formation process derailed by colonization. This is the foundation upon which later state-building experience rests.

Despite this history, when the EPRDF took power circa 1991, the Ethiopian state was in many ways little better prepared to deliver primary care at national scale than other countries in the region, which lacked Ethiopia’s ancient state tradition. While the imperial regime built national institutions like the civil service, universities, and public schools and hospitals, these state-building efforts were limited and ultimately halted by the 1974 revolution. The Derg regime’s (1974–91) efforts to further strengthen the state were limited by their repressiveness, infighting and massive diversion of resources into the military. The poor performance of the massive Derg military against lightly armed rural insurgencies and the regime’s inability to address the 1984–85 famine both demonstrate low Ethiopian state capacity through the 1980s.

Insurgent experiences

While the state that they inherited had been weakened, the TPLF could contribute valuable governing and state-building experience that they had accumulated in Tigray over the course of the insurgency period. As mentioned above, the TPLF benefitted from successful governance of the territory they controlled; a capability developed out of necessity, since the movement had limited economic resources and no external sponsor. As described in Barnabas and Zwi (1997 ), TPLF health leaders iterated, via trial and error, towards a functional PHC programme. Rather than a process of ‘isomorphic mimicry’ where external donors and experts prescribe externally generated models for health service delivery (Andrews et al., 2017), the TPLF went through a difficult but ultimately productive experience of learning how to deliver primary health services in ways that made sense for the Ethiopian context. Woldemariam (2018) describes such governing experiences by insurgent groups in Ethiopia as ‘laboratories of the future’ in which experiments in governance and service delivery could be carried out.

Yet while they had learned valuable lessons in Tigray, in the immediate post-war phase, the TPLF faced the challenge of scaling effective governance to all of Ethiopia. This challenge could not be separated from the ever-present ‘national question’ of how Ethiopia’s disparate nationalities and ethnicities could be integrated into a single polity. The TPLF represented ethnic Tigrayans who comprise <10% of the Ethiopian population. Building a state that could effectively deliver services to maintain support, while also accommodating this diversity, was a complex problem.

State-building strategies: centralization, mass mobilization and top-down accountability

TPLF leaders made several strategic state- and nation-building choices, which ultimately shaped their ability to implement PHC and other national programmes. The first was a strategy of hybrid federalism. They decided to shift from the integrationist model of the imperial and Derg regimes to instead pursue a federal structure in which each region would have their own political parties and regional governments, operating within regional borders redrawn to coincide with ethno-linguistic boundaries. Such federal structures are often viewed (as they were by many in Ethiopia) as appropriate redress for the historical regional inequities and can strengthen the representativeness and legitimacy of the political order, but they also imply substantial delegation of powers over policy, budget and human resources to local political actors, limiting the centre’s ability to aggressively implement national programmes (such as Ethiopia’s PHC initiatives).

However, the EPRDF’s strategic choices in this area preserved centralized power for national initiatives. The TPLF created a national coalition of ethnic parties by selecting and training a new set of local elites and local parties, instead of by coopting pre-existing elites and institutions. For example, they created the Oromia People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO) in Oromia region, rather than incorporating the existing Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), and encouraged the formation of ‘People’s Development Organization’ parties in other regions, staffed largely by cadres who were directly affiliated with the TPLF (Vaughan, 2011; Markakis, 2011; Lyons, 2019). In this way, despite the construction of a federalist state, EPRDF leaders retained significant direct authority over local actors. In addition, the EPRDF retained their ‘democratic centralist’ model of decision-making in which EPRDF decisions were taken centrally and then implemented using a hierarchical administrative structure (Lyons, 2019, pp. 80–2). Regional governments have significant legal autonomy, but de facto autonomy is limited: they have been governed by EPRDF member parties and also rely heavily on federal budgetary transfers.

This choice also brought real costs, risking the creation of regional parties with limited local legitimacy. These trade-offs were considered acceptable by the architects of the EPRDF regime, who viewed the developmental project as their highest priority. However, unresolved issues of regional representation re-emerged sharply in 2015, leading to political conflict, the resignation of then-Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn and ultimately to the reshaping of national politics under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed; a process that continues at the time of writing.

Building the state and managing it through top down accountability

Once the EPRDF had constructed a centralized decision-making structure with reliable local partners, a related state-building challenge was staffing and building capacity of lower-level government to fulfil Prime Minister Meles Zenawi’s developmental state programme. A major state-building effort commenced. After the 2001 party split, effective power was shifted from political party structure to state structures, and senior EPRDF cadres were placed in charge of ‘superministries’ including the new Ministry of Rural Capacity Building (Berhe, 2020a), and the EPRDF initiated a series of reforms aimed at strengthening woreda and kebele-level administration (Emmenegger, Keno, and Hagmann 2011). Vaughan (2011) notes that ‘the capacity building of state structures was a strongly political enterprise and accorded the highest government priority. By early 2004 at wereda level in many parts of the four EPRDF-administered regions, the Capacity Building bureau head emerged as the senior and most experienced party figure in the local administration, his political status regularly eclipsing that of the wereda chairman’.

Having staffed this structure, administrators and new cadres such as the "kebele manager" were then managed through top down accountability mechanisms, including a detailed performance management system, which each level of the administrative hierarchy was ranked based on their performance. These ratings mattered for promotions and were taken seriously. These state-building reforms, supported by donor funding, strengthened national institutions focused on development implementation. Initial planning for the national HEW programme dates to this period, and implementation was shaped by these state-building strategies and dynamics.

Mass mobilization and incorporation

This state-building effort was then shaped by electoral developments. In the period before the 2005 election, the EPRDF, confident in their popularity, allowed relatively open competition. They lost urban areas badly and faced unusually strong opposition showing, although the final election results remain disputed. After an initial period of direct repression (with several hundred killed in the immediate aftermath by security forces), this threat to the regime spurred a massive programme of expanding party and state structures at lower administrative levels to incorporate mass participation, coopt potential opposition and ensure regime support. The party grew from 700 000 members in 2005 to over 5 million in 2010 (Gilkes, 2015). Thousands of new government positions were created in local government, especially in health, education and agriculture (Vaughan, 2011; De Waal, 2015). These new cadres were seen both as a means of coopting potential opponents, as well as delivering public services in health, agricultural and other sectors, in both ways shoring up the regime’s political support (Lavers, 2019).

These emerging political needs of the regime fit well with the organizational needs of the HEP. Initial evaluations of the programme highlighted the need for more fundamental mobilization of communities, building on the model family structure, particularly in light of continued high levels of maternal mortality. At this point, the idea of the ‘Health Development Army’ emerged (Admasu, 2016). It combined intensification of the HEP model (desired by health policymakers) with the mass mobilization and party expansion initiatives, which were already underway for political reasons. In this new model, the HEWs were not the main conduit to citizens but rather they stood at the top of large hierarchy of volunteers; at community level, there was a 1:5 structure, whereby there would be a ‘model household’ for every five households in the country, in line with the agriculture extension structure (Østebø et al., 2018; Lyons, 2019). This created a unique administrative infrastructure to reach households with health messages and interventions.The result of this and the related state- and party-building activities was that, as Prime Minister Meles argued, ‘unlike all previous governments, our writ runs in every village. That has never happened in the history of Ethiopia’ (Matfess, 2015). Yet the political origins of the structure meant that the willingness of citizens to participate in 1:5 groups voluntarily varied across regions, and according to the dynamics of local politics (Emmenegger Keno and Hagmann 2011).

Structural challenges: the role of ideas

Another common challenge for primary healthcare programmes is ideological. The 1978 Alma Ata declaration is widely cited in Ethiopian policy documents, suggesting that international ideas about PHC were influential. However, several Ethiopia-specific ideologies and currents of thought were more important, most notably former PM Meles Zenawi’s distinctive conceptualization of the developmental state (De Waal, 2013; Gebregziabher, 2019). Meles’ ideas focused on the role of the state in fostering economic development; he was well-known for rejecting advice from donors about the need to limit the size of the state and liberalize Ethiopia’s economy (De Waal, 2013). Hiring 30 000-plus public sector HEWs was not on the donor policy agenda, but it fit in well with Meles’ state-centred developmental vision. Even more central to the PHC agenda was the idea that the state’s legitimacy would emerge from developmental progress, rather than by winning free and fair elections. This developmental progress, in Meles’ view, was only possible through the actions of an ‘autonomous state’, i.e. one that pursues a broad national interest (defined by the EPRDF leaders) instead of a state that was captured by rent-seeking individuals or groups.

This idea about state autonomy also helps explain why the EPRDF’s rural policies were implemented in a programmatic rather than clientelist way. The EPRDF’s focus on supporting rural dwellers is not completely unusual, especially in agrarian economies where most people live outside cities, but rural transfers are often implicitly used to maintain the ruling political coalition and distribute rents. The EPRDF’s ideological emphasis on programmatic rather than predominantly clientelist approaches to rural communities flows from this element of Meles’ thinking, as well as from earlier TLPF organizational culture and practices, which were instituted to avoid personalization and clientelist politics (Berhe, 2020a, pp. 54–5).

Other elements of the TPLF’s stated ideology of ‘revolutionary democracy’ (Gebregziabher, 2019) also affected how PHC programmes were implemented. One element of this ideology suggests that the state, given the absence of a large rural middle class, should engage directly with the rural population, rather than with local non-EPRDF elites. In Zenawi’s words, ‘in agricultural areas we do not make coalitions with elites: the only coalition we want to make is with the people’ (Vaughan, 2011). In practice, this meant inducing, and at times coercing, rural people to participate in state-organized developmental activities. The Health Development Army fit well into this ideological framework.

More directly, the idea of a national community health worker programme was modelled on previous initiatives, in the health sector as well as from the agriculture sector. A historical account from the International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia argues that ‘the ideation of HEP began from the “Model Family” approach initiated in 1997 by the Tigray Regional Health Bureau’, while others emphasize the earlier wartime community health worker programme, also in Tigray region (Barnabas and Zwi, 1997; Berhe, 2020b). To a lesser extent, the idea of PHC as the organizing principle of the health system started in the Derg years, including with focus on prevention and on primary interventions delivered by community workers (Kloos, 1998). Finally, Dr Tedros himself has pointed to Ethiopia’s agricultural extension programme as a model that policymakers drew on for the HEW programme (Witter and Awowsusi, 2017; International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019). There were thus a number of ideological currents and local policy models that supported primary health care, based on centrally-directed community mobilization and implemented by community health workers.

Structural challenges: financial barriers

In many developing countries in the post-Alma Ata period, large-scale primary healthcare programmes fell apart due to fiscal pressures, as governments faced economic crises and cut health budgets. Ethiopia certainly faced financial challenges with respect to its PHC investments: The primary healthcare investment programme (including the HEP) required an estimated $1.2 billion in start-up costs over 5 years (Workie and Ramana, 2013). By contrast, Ethiopia’s domestically financed government health expenditure circa 2007–08 was 2.5 billion Ethiopian Birr ($267 million).4 Ethiopia’s decision to hire over 30 000 HEWs and build over 2000 new health centres and over 15 000 health posts also generated significant recurrent costs. As of 2016, the HEW programme salary costs were $31.7 million annually (Wang et al., 2016), equivalent to 21% of the health sector recurrent budget. The HEW programme remains predominantly donor funded, with 74% of total cost covered by donors (International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019).

The Ethiopian government took on important financing responsibilities at the same time that it skilfully leveraged large health aid inflows. Much has been made of the decision by the Ethiopian government to take financial responsibility for the HEP, by making HEWs full government employees (at woreda level), in contrast to the lower cost voluntary HEW model favoured in other countries. The government’s assumption of this responsibility was critical; it avoided reliance on volunteer labour for this critical cadre, which had contributed to the demise of many other community health worker programmes (Perry et al., 2014).5 At the same time, the government shifted investment costs onto donors and, to a lesser extent, communities: local communities contributed labour and materials for the construction of health posts and donors contributed to training and to financing equipment and supplies for health posts. The government has also been slow to increase nominal salaries in the face of sustained inflation, decreasing the real income of HEWs, and the cost to government, over time.

Rapid economic growth also opened up some fiscal space: Ethiopia’s GDP grew 9.9% per year from 2003 to 2015, compared to the regional average of 5%.6 Yet while government health expenditure grew from $1.90 per capita in 1999/2000 to $3.20 in 2010–11, this was far surpassed by the increase in donor health aid, which grew from $0.90 to $10.40 per capita over the same period (World Bank, 2016). Development assistance for health grew sharply over this period for many developing countries. However, the Ethiopian government’s ability to attract resources for the health sector, and to do so on essentially its own terms, was unusually successful (Teshome and Hoebink, 2018). The country created and enforced aid management processes and institutions such as five year Health Sector Development Plans, a donor code of conduct, health aid coordination groups and several large pooled funding mechanisms that brought aid funds on budget and under government control. Equally important was Ethiopian policymakers’ skill in convincing donors to back the locally developed primary healthcare programme rather than verticalized programmes exclusively (Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2009). The Global Fund and GAVI, for example have been criticized for resisting health systems-focused investment in the heath workforce and facility construction, but for Ethiopia, they supported the construction of over 500 of the 2500 health centres that were built. The multi-donor Protection of Basic Services Project funded purchase of drugs, commodities and equipment for a large proportion of the health posts and health centres (International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019, p. 84; Lavers, 2019). Teshome and Hoebink (2018) highlight local ownership of health plans, strong technocratic leadership of the Ministry of Health and low corruption as contributors to the Ethiopian government success in mobilizing aid funds. This highlights how donor contributions to a sector can reflect not just aid dependence but can also reflect state capacity, as Ethiopian leadership’s investment in a more capable state attracted large aid inflows.

Discussion and conclusion

Ethiopia’s primary healthcare expansion is widely praised by leading global health organizations and leaders and is often seen as a model for primary care in low-income countries. External observers and Ethiopian policymakers alike stress ‘political will’ as the causal factor (Admasu, 2016; International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019), but few analyses unpack both the historical roots and the specific political and health policy strategies that enabled Ethiopia’s PHC programmes to be implemented at scale (Lavers, 2019; Ostebo et al., 2017).

This article highlights the ways that a primary healthcare programme based on community health workers and mass incorporation of the population was consistent with the broader political and developmental strategies of the EPRDF regime. In line with other analyses, this article finds that the characteristics of political leaders were critical, most notably Prime Minister Meles Zenawi’s developmental state vision for Ethiopia, and the ability of a series of Ministers of Health starting Dr Tedros Adhanom and Dr Kesetebirhan Admasu. Yet Meles died in 2012, Dr Tedros left the Ministry of Health in the same year, and despite this, progress has continued, with a series of highly regarded and dynamic ministers of health and continued ambitious health sector initiatives, such as the 2015–2020 Health Sector Transformation Plan. The Ethiopian primary healthcare experience cannot be completely reduced to the leadership of small number of individuals.

Rather than exclusively driven by ‘political will’ by an unusually dedicated Prime Minister or Minister of Health, Ethiopia’s primary healthcare programme is the result of a historical process, enabled by Ethiopia’s longstanding state traditions and rooted in policy experiments carried out by post-war political leaders during their previous experience as a guerilla army in northern Ethiopia. These experiences also led these leaders to believe strongly in prioritizing the welfare of rural Ethiopians as the foundation for their political success. Post-2001, the implementation of PHC at national level was enabled by a series of state-building strategies. These strategies were shaped by Ethiopia’s top-down model of federalism and the ruling party’s ideas about ensuring political stability and development through service delivery models that incorporated and coopted the Ethiopian population. These institutions supported service delivery but were also used to incorporate and control popular participation, even as other avenues for civic mobilization were closed off. These processes were influenced by global heath ideas about primary health care and supported by global funding streams. However, global ideas and funding were all reshaped in fundamental ways by local actors. These reformulated and adapted ideas about primary health care have in turn become influential and are widely cited in global forums, including by international organizations, which were originally sceptical about Ethiopia’s initiatives. This is an example of policy diffusion in global health of an approach originating from the global south and gaining broad influence (Edwards, 2020).

However, this narrative complicates any simple approach to translating Ethiopia’s model by other developing countries. First, the political unrest that began in Ethiopia in 2015 has demonstrated the limits to EPRDF’s top down approach. The liberalizing reforms implemented since 2018 by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed have implications for health programmes. In this climate, the mass mobilization components of the PHC programme, such as the Women’s Development Army, face increasing criticism: a recent review of the HEP conducted in 2018–19 states that WDA agents are now ‘mostly considered as political agents’ and recommends reforms to the structure (Merq Consultancy PLC, 2019, p. 21). Others have similarly argued that the project of using party-linked cadres to mobilize society for health and other development activities cannot easily be separated from the imposition of social and political control (Maes et al., 2015) and that this is unsustainable in a polity undergoing liberalizing reforms (De Freytas-Tamura, 2017; Fick, 2019).7

Yet even if these elements of the PHC programme are reformed or discarded, the programmatic orientation of public policy prioritizing rural areas, combined with investment in state building and implementation, provides a foundation for continued health system strengthening. Several middle-income countries demonstrate the power of such rural-based political coalitions to drive health investment: At roughly, the same time period that Ethiopia was implementing its PHC programmes, for example both Thailand and Turkey saw the election of populist leaders with rural political bases who passed and led the implementation of ambitious programmatic health reforms (McCargo and Zarakol, 2012; Harris, 2015; Sparkes Bump and Reich, 2015).

There has also been recent critical analysis of the effectiveness of the primary care model, including whether the HEW service packages, largely focused on health education and prevention, remain the most important priority, as the burden of disease changes over time. Globally, there is a renewed emphasis that health system quality must go hand in hand with expanded access (Kruk et al., 2018), while in Ethiopia, a recent study found that Ethiopia’s large-scale health facility construction programme increased the utilization of health services but was not associated with reduced neonatal mortality (Croke et al., 2020). In recent reviews of the HEP, demand for higher quality care and better-equipped health posts with more consistent drug supply has been highlighted (International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia, 2019). Programme reviews have also highlighted growing dissatisfaction on the part of HEWs, who remain modestly paid with large populations to serve, continuously broadening scope of activities, and limited paths for promotion within the health system (Merq Consultancy PLC, 2019).

Yet other Ethiopia’s experiences still contain lessons for other countries, even if the specific historical circumstances obviously cannot be imitated. One point is that ‘political will’ is powerless without functional state institutions. Yet political will can be exerted in support of a state strengthening project. In Ethiopia, the desire to deliver services to rural communities was enabled by investment in the personnel and systems at local level, including meaningful mechanisms of performance management and accountability. It is also notable that the ideas and political pressures that motivated this state-building project were locally generated and differed significantly from global ‘best practice’ institutions. The HEP ran counter to mainstream donor thinking circa 2003, as did the whole range of local governance institutions. Yet these heterodox local institutions appear to have generated rapid improvements in access to a range of rural public services, including primary health care.

From a theoretical perspective, this article highlights both the path dependency of development processes, as well as their contingency and the role of leaders and ideas. A major argument of the article is that Ethiopia’s primary health reforms were deeply shaped by the country’s history, including long-term processes of state formation and, more importantly, the wartime circumstances that led the TPLF to develop rural-focused policies, including primary health care. But the process by which these elements were translated into a sustained national programme was subject to contingency and individual agency. It also highlights an important role for the subjective ideas and understandings of political leaders (Lavers, 2018), and political organizations that can diffuse and institutionalize those ideas. Ethiopia’s innovative health policies were not national priorities, even under EPRDF rule, until after the 2001 ruling party split and the resulting consolidation of power under Meles Zenawi. Meles’ distinctive ideas about the developmental state and how to ensure programmatic rather than rent-seeking policies, and the organizational forms and ideological apparatus of the EPRDF, were central to the implementation of primary healthcare programmes. This contingency is highlighted again by the current political uncertainty in Ethiopia, the resolution of which is likely to affect the future of health policies and primary health care.

The limitations of this article are that it is a single case study and that it is largely based on the secondary literature, which may emphasize positive aspects of Ethiopia’s post-1991 trajectory, especially given the political sensitivities around the regime and lack of freedom of expression in EPRDF-governed Ethiopia. Trends in governance and key health service indicators from comparator countries are presented, but Ethiopia is a relatively unique country and it is difficult to identify ideal comparators. More work is needed to place the Ethiopian case in comparative perspective. Despite these limitations however, the Ethiopian case offers insights about the factors that contribute to the implementation of primary healthcare programmes at scale in low-income countries, and attempts by other countries in the region to implement PHC programmes of comparable scale and ambition may benefit from the consideration of this experience.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a grant from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement.

Ethical approval. This project was approved by the Harvard Longwood Medical Area IRB, proposal IRB19-1743.

Endnotes

Interview with Dr Tedros, June 19, 2013, https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2013/public-health-health-care-payers-providers-adhanom-ghebreyesus-transforming-health-care-in-ethiopia, last accessed September 3, 2020.

One exception is Harris (2015) who theorizes about the ‘developmental capture’ of the Thai state led to health reform. Lavers (2019) considers similar issues in the Ethiopian context.

These countries are the six largest by population in sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa.

https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Ethiopia-NHA-Findings-Briefing-Notes.pdf, last accessed August 22, 2020 see table 2.

By contrast, the Health Development Army was all unpaid volunteers.

Author’s calculations from World Bank data, accessed at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=ET, last accessed August 22, 2020.

A related criticism of the EPRDF party-state comes from Berhe (2020a), who argues that the gradual merging of party and state has led to decline in state capacity compared to the earlier, more meritocratic and participatory TPLF model.

References

- Admasu KB. 2016. Designing a resilient national health system in Ethiopia: the role of leadership. Health Systems & Reform 2: 182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M, Pritchett L, Woolcock M.. 2017. Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa Y, Gelaw YA, Hill PS, Taye BW, Van Damme W.. 2019. Community Health Extension Program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Globalization and Health 15: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanova D, Mills A, Conteh L, et al. 2013. Good health at low cost twenty five years on: lessons for the future of health system strengthening. The Lancet 381: 2118–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnabas G, Zwi A.. 1997. Health policy development in wartime: establishing the Baito health system in Tigray. Health Policy and Planning 12: 38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhe MG. 2020. a. Laying the Past to Rest: The EPRDF and the Challenges of Ethiopian State-Building. London: Hurst Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Berhe MG. 2020. b. Barefoot Doctors and Pandemics: Ethiopia’s Experience and COVID-19 in Africa https://africanarguments.org/2020/04/08/barefoot-doctors-and-pandemics-ethiopias-experience-and-covid-19-in-africa/. Last accessed August 22, 2020.

- Berwick E, , Christia F. 2018. State Capacity Redux: Integrating Classical and Experimental Contributions to an Enduring Debate. Annual Review of Political Science 21: 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009. Ethiopia extends health to its people 87: 485–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham C. 2017. The Horn of Africa: State Formation and Decay. London: Hurst and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham C. 2018. The Ethiopian developmental state. Third World Quarterly 39: 1151–65. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), ORC Macro. 2001. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Addis Ababa and Calverton, MD: Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia and ORC Macro.

- Croke K, Mengistu A, O’Connell S, Tafere K.. 2020. The impact of a health facility construction campaign on health service utilization and outcomes: analysis of spatially-linked survey and facility location data in Ethiopia. BMJ Global Health, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- De Freytas-Tamura K. 2017. ‘We are everywhere’: how Ethiopia became a land of prying eyes. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/05/world/africa/ethiopia-government-surveillance.html. Last accessed August 22, 2020.

- De Waal A. 2013. The theory and practice of Meles Zenawi. African Affairs 112: 148–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal A. 2015. The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa: Money War and the Business of Power. Malden, MA: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Z. 2020. Postcolonial sociology as a remedy for global diffusion theory. The Sociological Review. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia Public Health Institute, Federal Ministry of Health, ICF. 2019. Mini-Demographic and Health Survey: Key Indicators https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR120/PR120.pdf.

- Federal Ministry of Health (Ethiopia). 2019. National Health Accounts 2016/17 http://www.moh.gov.et/ejcc/sites/default/files/2020-01/Ethiopia%207th%20Health%20Accounts%20Report_2016-17.pdf.

- Fick M. 2019. Ethiopia's surveillance network crumbles, meaning less fear and less control. Reuters, December 17, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-politics-surveillance-insigh/ethiopias-surveillance-network-crumbles-meaning-less-fear-and-less-control-idUSKBN1YL1C2.

- Fox AM, Balarajan Y, Cheng C, Reich MR.. 2015. A rapid assessment tool to measure political commitment to food and nutrition security. Health Policy and Planning 30: 566–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebregziabher TN. 2019. Ideology and power in TPLF’s Ethiopia: a historic reversal in the making? African Affairs 118: 463–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J. 2004. What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review 98: 341–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J. 2008. Case selection for case‐study analysis: qualitative and quantitative techniques. In: Box-Steffensmeier JM, Brady HE, and Collier D (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, pp. 645-684. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gilkes P. 2015. Elections and Politics in Ethiopia 2005-2010. In: Ficquet E, Prunier G (eds.) Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution, and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman A, Keller JM, Lu J.. 2018. The Declaration of Alma-Ata at 40: Realizing the Promise of Primary Health Care and Avoiding the Pitfalls in Making Vision Reality Center for Global Development working paper. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/Glassman-Declaration-Alma-Ata-40-final.pdf.

- Harris J. 2015. “Developmental capture” of the state: explaining Thailand's universal coverage policy. J Health Polit Policy Law 40: 165–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst J. 2000. States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Primary Health Care – Ethiopia. 2019. Evolution of Health Extension Program in Ethiopia: Past, Present, and Future.

- Kloos H. 1998. Primary health care in Ethiopia under three political systems: community participation in a war-torn society. Social Science and Medicine 46: 502–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C. et al. 2018. High Quality Health Systems in the Sustainable Development Goals Era: time for a Revolution. The Lancet Global Health 6: e1196–e1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavers T. 2018. Taking Ideas Seriously within Political Settlements Analysis. ESID working paper 95.

- Lavers T. 2019. Towards Universal Health Coverage in Ethiopia’s ‘developmental state’?: The political drivers of Community-Based Health Insurance Social Science and Medicine 228: 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maes K, Closser S, Vorel E, Tesfaye Y.. 2015. A women’s development army: narratives of community health worker investment and empowerment in rural Ethiopia. Studies in Comparative International Development 50: 455–78. [Google Scholar]

- Markakis J. 2011. Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers. Woodbridge: James Currey. [Google Scholar]

- Matfess H. 2015. Rwanda and Ethiopia: developmental authoritarianism and the new politics of African strong men. African Studies Review 58: 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- McCargo D, Zarakol A.. 2012. Turkey and Thailand: unlikely twins. Journal of Democracy 23: 71–9. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J. 2010. Wealth, Health, and Democracy in East Asia and Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merq Consultancy PLC. 2019. National assessment of the Ethiopian Health Extension Program. http://repository.iifphc.org/handle/123456789/560.

- Østebø M T, , Cogburn M D, , Mandani A S. 2018. The silencing of political context in health research in Ethiopia: why it should be a concern. Health Policy and Planning 33: 258–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard RM. 2016. A History of Global Health: Interventions into the Lives of Other Peoples. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry HB, , Zulliger R, , Rogers MM. 2014. Community Health Workersin Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: An Overview of Their History,Recent Evolution, and Current Effectiveness. Annual Review of Public Health 35: 399–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin S. 2018. Alma Ata after 40 years: primary health care and health for all—from consensus to complexity. BMJ Global Health 3: e001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes SP, Bump JB, Reich MR.. 2015. Political strategies for health reform in Turkey: extending veto point theory. Health Systems & Reform 1: 263–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse M. 2015. The Tigay People's Liberation Front.In: Prunier G, Ficquet E (eds.) Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution, and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teshome SB, Hoebink P.. 2018. Aid, ownership, and coordination in the health sector in Ethiopia. Development Studies Research 5: S40–S55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tesfaye R, Ramana GNV, Chekagh CT.. 2016. Ethiopia Health Extension Program: An Institutionalized Community Approach for Universal Health Coverage. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Willis B. 2014. The advantages and limitations of single case study analysis. E-international relations. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0912/0ea06684457c89c56184a46e83d3f7834bd8.pdf?_ga=2.251106624.771413045.1592919866-1807458858.1592919866.

- Witter S, Awowsusi A.. 2017. Ethiopia and the Health Extension Worker Program. Oxford policy management case study. https://learningforaction.org/wp-content/uploads/Learning-for-action-across-health-systems_Ethiopia-cast-study-1.pdf.

- Woldemariam M. 2018. Insurgent Fragmentation in the Horn of Africa: Rebellion and Its Discontents. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Workie NW, , Ramana GMV. 2013. The Health Extension Program in Ethiopia. World Bank Universal Health Coverage Series 10. Washington DC: WorldBank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Ethiopia Public Expenditure Review 2016. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2000. World Health Report: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008. World Health Report: Primary Health Care – Now More than Ever. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]