Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive esophagectomy and gastrectomy are increasingly performed and might be superior to their open equivalents in an elective setting. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether minimally invasive approaches can be safely applied in the acute setting as well.

Methods

All patients who underwent an acute surgical intervention for primary esophageal or gastric cancer between 2011 and 2017 were identified from the nationwide database of the Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit (DUCA). Conversion rates, postoperative complications, re-interventions, postoperative mortality, hospital stay and oncological outcomes (radical resection rates and median lymph node yield) were evaluated.

Results

Between 2011 and 2017, surgery for esophagogastric cancer was performed in an acute setting in 2% (190/8861) in The Netherlands. A total of 14 acute resections for esophageal cancer were performed, which included 7 minimally invasive esophagectomies and 7 open esophagectomies. As these numbers were very low, no comparison between minimally invasive and open esophagectomies was made. A total of 122 acute resections for gastric cancer were performed, which included 39 minimally invasive gastrectomies and 83 open gastrectomies. Conversion occurred in 9 patients (23%). Minimally invasive gastrectomy was at least comparable to open gastrectomy regarding postoperative complications (36% versus 51%), median hospital stay (9 days [IQR: 7–16 days] versus 11 days [IQR: 7–17 days]), readmissions (8% versus 11%) and oncological outcomes (radical resection rate: 87% versus 66%, median lymph node yield: 21 [IQR: 15–32 days] versus 16 [IQR: 11–24 days]).

Conclusions

Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer is safe and feasible in the acute setting, with at least comparable postoperative clinical and short-term oncological outcomes compared to open surgery but a relatively high conversion rate.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Gastric cancer, Acute surgery, Minimally invasive surgery, Open surgery, Postoperative complications, Oncological outcomes

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are increasingly being applied in the surgical treatment of esophageal and gastric cancer [1, 2]. Evidence from randomized controlled trials and nationwide studies suggests that these techniques might provide benefits over the traditional open approaches, especially regarding short-term outcomes in terms of postoperative morbidity and length of hospital stay [3–12]. In contrast, higher reintervention rates were observed after minimally invasive esophagectomies in population-based studies [5–8]. As the aforementioned studies only included patients who underwent an elective surgical resection, the generalizability of these results to the acute setting might be limited.

Acute surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer is relatively rare and is usually only performed in case tumors are actively bleeding or have perforated. These cases are different from the usual elective patient population and might therefore be more difficult to treat with minimally invasive surgical techniques. More research is warranted to investigate the role of minimally invasive surgical techniques for patients with esophageal and gastric cancer who have an acute indication for a resection. Therefore, the aim of this nationwide cohort study was to describe the postoperative outcomes of minimally invasive as compared to open acute surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer.

Methods

Study design

This nationwide observational cohort study was conducted with data from the Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit (DUCA), a nationwide registration of all patients undergoing surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer since 2011 [13]. Registration of cases in the DUCA is mandatory for each hospital and includes patient characteristics, treatment details including the timing of surgery, postoperative outcomes (until 30 days after surgery), and pathological outcomes. The scientific committee of the DICA and DUCA approved this study. No ethical approval or informed consent was required under Dutch law.

Study population and treatment

All patients who underwent acute surgery with the intention to perform an esophagectomy or gastrectomy for cancer between 2011 and 2017 were selected from the DUCA registry. Patients were diagnosed according to the Dutch national guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, follow up, and guidance of patients for patients with esophageal and gastric cancer [14, 15]. Acute surgical interventions were either defined as emergent (i.e., surgery scheduled < 12 h after presentation with an acute indication) or urgent (surgery scheduled > 12 h—but not electively—after presentation with an acute indication). Both were included in the current study. Exclusion criteria were prophylactic surgical indications (i.e., no proven malignancy), insufficient data regarding the tumor or surgical approach, and surgery for cancer recurrence.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures included the rates of conversion to an open procedure, postoperative complications, re-interventions, postoperative mortality (i.e., mortality during initial hospital admission or within 30 days after surgery), length of postoperative stay on the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and in hospital, as well as readmissions (< 30 days after discharge). Complications were defined according to standards of the DUCA, and included pulmonary complications (clinically proven pneumonia, pleural effusion leading to drainage, pleural empyema and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome), anastomotic leakage (either by clinical or radiological diagnosis), cardiac complications (supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia, myocardial infarction and/or heart failure), thromboembolic complications (pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, stroke and/or thrombophlebitis), neurologic complications (recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and/or acute delirium), urologic complications (urinary tract infection, urinary retention and/or renal insufficiency), intra-abdominal abscess, chyle leakage, fascia dehiscence and wound infections. Furthermore, oncological outcomes in terms of radicality and total lymph node yield were analyzed. A radical resection (i.e., R0) was defined as the absence of tumor cells within the resection margins of the resection specimen.

Statistical analyses

Patient and treatment characteristics were described as counts with percentages, mean (± standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). The postoperative outcomes were separately described for patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery and open surgery. No tests for statistical significance of differences between groups were performed because of inability to adequately correct for confounding bias due to small group sizes. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study population

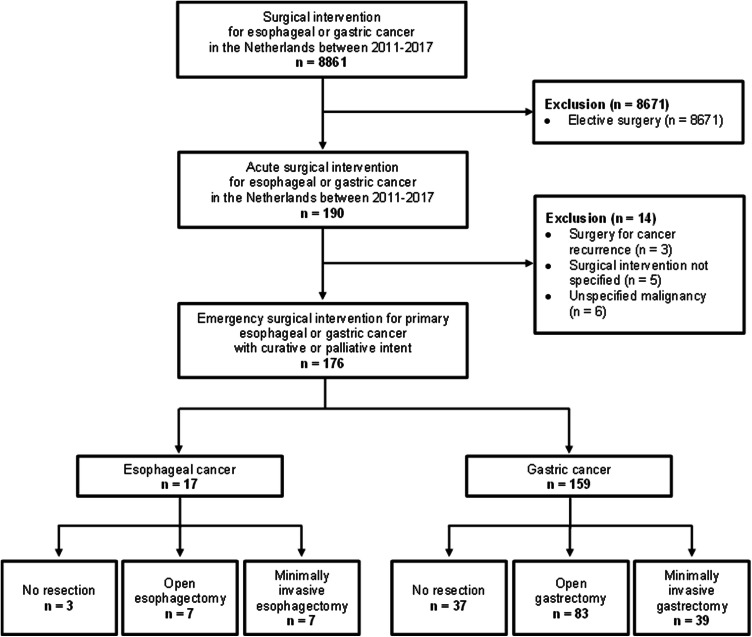

Between 2011 and 2017, a total of 8861 patients who underwent surgery for esophageal or gastric cancer in the Netherlands were registered in the DUCA. Surgery was performed in an acute setting in 190 out of these 8861 patients (2%). Patients who underwent an unspecified surgical intervention (n = 5), a surgical procedure for cancer recurrence (n = 3), or a surgical procedure for an unspecified malignancy (n = 6) were excluded. Hence, a total of 176 patients were included, of whom 17 patients with esophageal cancer and 159 patients with gastric cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart

Acute surgical interventions for esophageal cancer

Acute surgical interventions for esophageal cancer were performed in 17 patients and were with curative intent in all of these patients. The median number of days between the diagnostic biopsy and surgery was 70 days (IQR 46–121 days). In 2 patients (12%), no histologic diagnosis was present prior to surgery. The reason for surgery was a perforation in 7 patients (41%), bleeding in 5 patients (29%) and other (not specified) in the remaining 5 cases (29%). Esophagectomy was performed in 14 out of these 17 patients (82%); by a minimally invasive transhiatal approach in 4 patients, an open transhiatal approach in 5 patients, a minimally invasive transthoracic approach in 3 patients, and an open transthoracic approach in 2 patients. The remaining 3 patients (18%) underwent a surgical procedure without resection, which involved a diagnostic laparoscopy in 2 patients and a diagnostic thoracotomy in 1 patient. A complete overview of patient and treatment characteristics of the esophageal cancer patients is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent an acute surgical intervention for esophageal cancer in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2017

| Characteristics | All | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 17 | % | |

| Patient-related characteristics | ||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 64 ± 11 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 15 | 88% |

| Female | 2 | 12% |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 26 ± 5 | |

| ASA classification | ||

| I | 2 | 12% |

| II | 7 | 41% |

| III | 7 | 41% |

| IV | 1 | 6% |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Cardiac | 2 | 12% |

| Vascular | 8 | 47% |

| Diabetes | 5 | 29% |

| Pulmonary | 3 | 18% |

| Previous abdominal or thoracic surgery | 7 | 41% |

| Tumor location | ||

| Middle esophagus | 1 | 6% |

| Distal esophagus | 9 | 53% |

| Gastro-esophageal junction | 5 | 29% |

| Unknown | 2 | 12% |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 15 | 88% |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 | 6% |

| Other | 1 | 6% |

| cT statusa | ||

| T1 | 3 | 18% |

| T2 | 2 | 12% |

| T3 | 5 | 29% |

| T4 | 5 | 29% |

| Tx | 2 | 12% |

| cN statusa | ||

| N0 | 6 | 35% |

| N+ | 8 | 47% |

| Nx | 3 | 18% |

| cM statusa | ||

| M0 | 13 | 76% |

| M1 | 2 | 12% |

| Mx | 2 | 12% |

| Treatment-related characteristics | ||

| Neoadjuvant therapyb | ||

| None | 10 | 59% |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 4 | 24% |

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 12% |

| Radiotherapy | 1 | 6% |

| Setting | ||

| Emergent (< 12 h) | 10 | 59% |

| Urgent (> 12 h) | 8 | 41% |

| Reason for emergency surgery | ||

| Bleeding | 5 | 29% |

| Perforation | 7 | 41% |

| Other/unknown | 5 | 29% |

| Surgical approach | ||

| Minimally invasive | 9 | 53% |

| Open | 8 | 47% |

| Surgical procedure | ||

| Transhiatal esophagectomy | 9 | 53% |

| Transthoracic esophagectomy | 5 | 29% |

| Diagnostic thoracotomy | 1 | 6% |

| Diagnostic laparoscopy | 2 | 12% |

| Reconstruction | ||

| Gastric conduit reconstruction | 12 | 71% |

| No reconstruction | 4 | 24% |

| Unknown | 1 | 6% |

| Location of anastomosis | ||

| Cervical | 10 | 59% |

| Intrathoracic | 2 | 12% |

| Not applicable | 5 | 29% |

| Lymph node dissection | 13 | 76% |

| Year of surgery | ||

| 2011–2013 | 9 | 53% |

| 2014–2017 | 8 | 47% |

Data are numbers of patients with column-based percentages in parentheses, unless otherwise stated

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI body mass index at diagnosis; SD standard deviation

aClinical T status and N status are based on AJCC TNM 7th edition

bThe standard regimen for neoadjuvant treatment for esophageal cancer patients in the Netherlands consists of carboplatin and paclitaxel, weekly during 5 weeks, and concurrent radiotherapy with a total radiation dose of 41.4 Gy in 23 fractions of 1.8 Gy. For gastro-esophageal junction or gastric adenocarcinoma, peri-operative treatment generally consists of chemotherapy regimens similar to the MAGIC-trial (epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine)

Perioperative and oncological outcomes of the 14 patients who underwent esophagectomy are shown in Table 2. The outcomes were not reported for minimally invasive esophagectomy and open esophagectomy separately, as the number of patients for both groups was only 7. Postoperative complications occurred in 50% (7/14). Pulmonary complications were most common (43%, 6/14), followed by anastomotic leakage (29%, 4/14). The median length of hospital stay was 13 days (IQR: 11–26 days). No patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after discharge.

Table 2.

Short-term outcomes for patients who underwent an acute esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2017

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| n = 14 | % | |

| Peroperative outcomes | ||

| Conversiona | 1 | 7% |

| Postoperative complications | ||

| All | 7 | 50% |

| Pulmonaryb | 6 | 43% |

| Anastomotic leakagec | 4 | 29% |

| Cardiacd | 1 | 7% |

| Chyle leakage | 0 | 0% |

| Re-interventions | 1g | 7% |

| Recovery | ||

| ICU duration (median, IQR) | 3 | (1–6) |

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 13 | (11–26) |

| Postoperative mortalitye | 1 | 7% |

| Readmission to hospitalf | 0 | 0% |

| Pathological outcomes | ||

| Radicality | ||

| R0 | 9 | 64% |

| R1 | 5 | 36% |

| Lymph node yield (median, IQR) | 21 | (12–26) |

| Positive lymph nodes harvested (median, IQR) | 3 | (1–10) |

There were no missing values for the variables described in this table

IQR interquartile range, NA not applicable

aConversion > 30 min after start of surgery because of peroperative bleeding

bPneumonia, pleural effusion, respiratory failure, pneumothorax and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome

cAny clinically or radiologically proven anastomotic leakage

dSupraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia, myocardial infarction and/or heart failure

eDeath during initial hospital admission or within 30 days after surgery

fReadmission to hospital within 30 days after initial discharge

gRe-operation for anastomotic leakage

Histopathological evaluation of the resection specimen showed that a radical resection was achieved in 64% (9/14). The median lymph node yield was 21 (IQR: 12–26 days).

Acute surgical interventions for gastric cancer

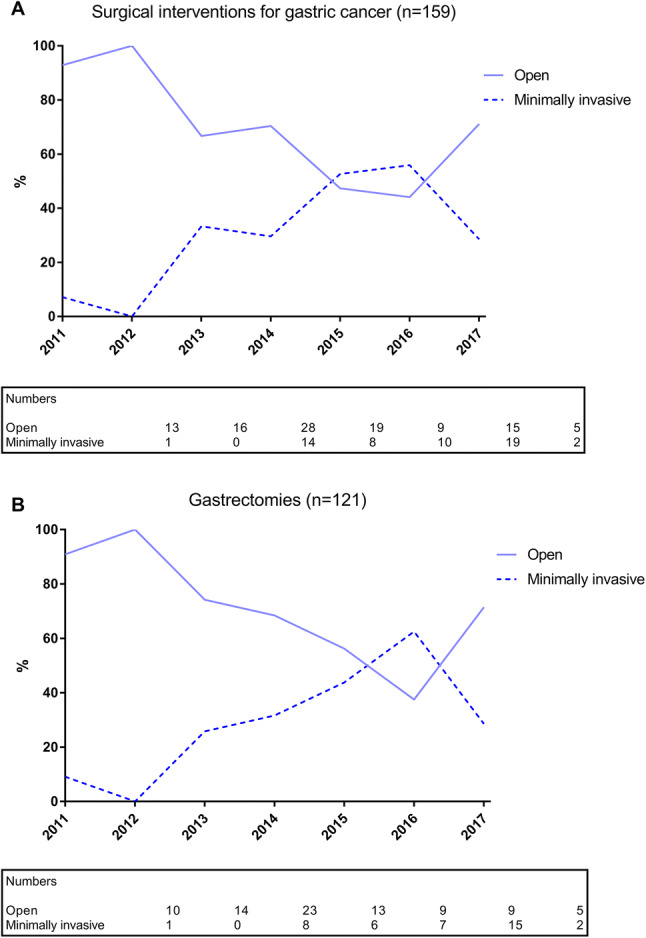

An acute surgical intervention for gastric cancer was performed in 159 patients, with an upfront curative intent in the majority of patients (70%). The median time between diagnostic biopsy and acute surgery was 23 days (IQR 11–36 days). Histological confirmation of gastric cancer was not present prior to surgery in 25 patients (16%). The reason for surgery was a bleeding in 68 patients (43%), perforation in 19 patients (12%) and other (not specified) in the remaining 73 patients (46%). Gastrectomy was performed in 122 patients (77%), which was by a minimally invasive approach in 39 patients and by an open approach in 83 patients. The remaining 37 patients (23%) underwent a surgical procedure without resection, which involved a gastroenterostomy in 26 patients, diagnostic laparoscopy in 6 patients and a diagnostic laparotomy in 5 patients. Most minimally invasive procedures were observed in the more recent years (Fig. 2). A complete overview of patient and treatment-related characteristics of the gastric cancer patients is presented in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Minimally invasive and open surgical interventions (A) and gastrectomies (B) for acute presentation of gastric cancer in the study period

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent an acute surgical intervention for gastric cancer in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2017

| Characteristics | Open | Minimally invasive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 105 | % | n = 54 | % | |

| Patient-related characteristics | ||||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 71 ± 10 | 71 ± 12 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 79 | 75 | 33 | 61 |

| Female | 26 | 25 | 21 | 39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | ||

| ASA classification | ||||

| I | 8 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| II | 39 | 37 | 25 | 46 |

| III | 46 | 44 | 23 | 43 |

| IV | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| V | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Not specified | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiac | 35 | 33 | 24 | 44 |

| Vascular | 42 | 40 | 27 | 50 |

| Diabetes | 22 | 21 | 10 | 19 |

| Pulmonary | 23 | 22 | 11 | 20 |

| Previous abdominal or thoracic surgery | 37 | 35 | 18 | 33 |

| Tumor location | ||||

| Fundus | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Corpus | 28 | 27 | 12 | 22 |

| Antrum | 48 | 46% | 22 | 41 |

| Pylorus | 12 | 11 | 12 | 22 |

| Stomach | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Other/not specified | 8 | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 88 | 84 | 49 | 91 |

| Other | 8 | 8 | 4 | 7 |

| Not specified | 9 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| cT statusa | ||||

| T1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| T2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| T3 | 32 | 30 | 20 | 37 |

| T4 | 18 | 17 | 10 | 19 |

| Tx | 43 | 41 | 13 | 24 |

| cN statusa | ||||

| N0 | 26 | 25 | 19 | 35 |

| N+ | 46 | 44 | 28 | 52 |

| Nx | 33 | 31 | 7 | 13 |

| cM statusa | ||||

| M0 | 76 | 72 | 44 | 81 |

| M1 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 7 |

| Mx | 20 | 19 | 6 | 11 |

| Treatment-related characteristics | ||||

| Neoadjuvant therapyb | ||||

| None | 93 | 89 | 52 | 96 |

| Chemotherapy | 11 | 10 | 2 | 4 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Setting | ||||

| Emergent (< 12 h) | 37 | 35 | 8 | 15 |

| Urgent (> 12 h) | 68 | 65 | 46 | 85 |

| Reason for acute surgery | ||||

| Bleeding | 41 | 39% | 26 | 48 |

| Perforation | 17 | 16% | 2 | 4 |

| Other | 47 | 45% | 26 | 48 |

| Surgical procedure | ||||

| Total gastrectomy | 26 | 25% | 8 | 15 |

| Partial gastrectomy | 57 | 54% | 31 | 57 |

| Bypass (gastroenterostomy) | 17 | 16% | 9 | 17 |

| Diagnostic laparotomy/laparoscopy | 5 | 5% | 6 | 11 |

| Intention | ||||

| Curative intent | 74 | 70% | 43 | 80 |

| Palliative intent | 26 | 25% | 8 | 15 |

| Not specified | 5 | 5% | 3 | 6 |

| Lymph node dissection | 64 | 61% | 35 | 65 |

| Year of surgery | ||||

| 2011–2013 | 57 | 54% | 15 | 28 |

| 2014–2017 | 48 | 46% | 39 | 72 |

Data are numbers of patients with column-based percentages in parentheses, unless otherwise stated

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI body mass index at diagnosis; SD standard deviation

aClinical T status and N status are based on AJCC TNM 7th edition

bThe standard regimen for peri-operative treatment for gastro-esophageal junction or gastric adenocarcinoma generally consists of chemotherapy regimens similar to the MAGIC-trial (epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine)

Perioperative and oncological outcomes of the 122 patients who underwent a gastrectomy are shown in Table 4. Conversion to an open procedure occurred in 9 of the 39 minimally invasive gastrectomies (23%), mostly because of the extent of the tumor and poor exposure (Table 4). Postoperative complications occurred in 14 of the 39 patients who underwent a minimally invasive gastrectomy (36%) and in 42 of the 83 patients who underwent an open gastrectomy (51%). When comparing minimally invasive gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy, pulmonary complications occurred in 13% versus 18%, anastomotic leakage in 8% versus 8%, and wound infection in 0% versus 13%, respectively. Re-interventions, mostly for anastomotic leakage in both groups, were performed in 23% after a minimally invasive gastrectomy versus 14% after an open gastrectomy. Postoperative mortality occurred in 8% after a minimally invasive gastrectomy versus 11% after an open gastrectomy. The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (IQR: 7–16 days) after minimally invasive gastrectomy versus 11 days (IQR: 7–17 days) after open gastrectomy. Readmission to the hospital was seen in 8% after minimally invasive gastrectomy versus 11% after open gastrectomy.

Table 4.

Short-term outcomes for patients who underwent an acute gastrectomy for gastric cancer in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2017

| Open | Minimally invasive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 83 | % | n = 39 | % | ||||

| Peroperative outcomes | |||||||

| Conversion | NA | 9 | 23% | ||||

| Reasons for conversion | NA | ||||||

| Tumor extent | 4 | 10% | |||||

| Poor exposure | 4 | 10% | |||||

| Peroperative complication | 1 | 3% | |||||

| Postoperative complications | |||||||

| Alla | 42 | 51% | 14 | 36% | |||

| Medical complications | |||||||

| Pulmonaryb | 15 | 18% | 5 | 13% | |||

| Cardiacc | 7 | 8% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Thromboembolicd | 4 | 5% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Neurologice | 4 | 5% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Urologicf | 4 | 5% | 1 | 3% | |||

| Intra-abdominal complications | |||||||

| Anastomotic leakageg | 7 | 8% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Abscess | 4 | 5% | 1 | 3% | |||

| Chyle leakage | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Wound complications | |||||||

| Fascia dehiscence | 2 | 2% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Wound infectionh | 11 | 13% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Other | 11 | 13% | 5 | 5% | |||

| Re-interventions | |||||||

| Alla | 12 | 14% | 9 | 23% | |||

| Surgical | 11 | 13% | 6 | 15% | |||

| Radiologic | 3 | 4% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Endoscopic | 2 | 2% | 1 | 3% | |||

| Not specified | 0 | 0% | 1i | 3% | |||

| Causes for re-interventions | |||||||

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 | 6% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Fascia dehiscence | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Complication of feeding jejunostomy | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% | |||

| No complication encountered | 3 | 4% | 2 | 5% | |||

| Other | 3 | 4% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Recovery | |||||||

| ICU duration (median, IQR) | 1 | (0–2) | 1 | (0–1) | |||

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 11 | (7–17) | 9 | (7–16) | |||

| Postoperative mortalityj | 9 | 11% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Readmission to hospitalk | 9 | 11% | 3 | 8% | |||

| Oncological outcomes | |||||||

| Radicality | |||||||

| R0 | 55 | 66% | 34 | 87% | |||

| R1 | 14 | 17% | 3 | 8% | |||

| R2 | 11 | 13% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Lymph node yield (median, IQR) | 16 | (11–24) | 21 | (15–32) | |||

| Positive lymph nodes harvested (median, IQR) | 4 | (0–9) | 5 | (1–10) | |||

IQR interquartile range, NA not applicable

Missing values were encountered in ICU duration (n = 12), length of stay (n = 2), readmission (n = 4), radicality (n = 5), lymph node yield (n = 2) and positive lymph nodes harvested (n = 2)

aDefined as number of patients who experienced a postoperative complication or underwent a reintervention. One patient could experience more than 1 complication or reintervention

bPneumonia, pleural effusion, respiratory failure, pneumothorax and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome

cSupraventricular and ventricular arrhythmia, myocardial infarction and/or heart failure

dPulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, stroke and/or thrombophlebitis

eAcute delirium

fUrinary tract infection, urinary retention and/or renal insufficiency

gAny clinically or radiologically proven anastomotic leakage

hWound infection requiring drainage or antibiotic treatment

iPatient who underwent a reintervention for a complication of the feeding jejunostomy

jDeath during initial hospital admission or within 30 days after surgery

kReadmission to hospital within 30 days after initial discharge

Histopathological evaluation of the resection specimen showed that a radical resection was achieved in 34 of the minimally invasive gastrectomies (87%) and in 55 of the open gastrectomies (66%). The median lymph node yield was 21 (IQR: 15–32 days) after minimally invasive gastrectomy and 16 (IQR: 11–24 days) after open gastrectomy.

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study concerning patients who underwent acute surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer, short-term postoperative and oncological outcomes of minimally invasive resections were comparable to open resections..

Previous studies have shown the safety and feasibility of minimally invasive surgery for esophagogastric cancer in the elective setting [3–12]. For esophageal cancer, minimally invasive esophagectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, higher lymph node yield, similar radical resection rate and postoperative pulmonary complications, but higher reintervention rates in several population-based studies [5–8]. Due to the low number of acute esophagectomies, it was unfortunately not possible in this study to perform the analyses that would be required to reproduce these results for minimally invasive esophagectomy in the acute setting. For gastric cancer, minimally invasive gastrectomy in the elective setting was deemed to be safe and feasible regarding overall postoperative morbidity and mortality rates, as well as short-term oncological outcomes, and resulted in decreased wound complications and a shorter hospital stay compared to open gastrectomy [10, 12]. The current study of minimally invasive gastrectomy in the acute setting also demonstrated comparable oncological outcomes to the open approach, as well as a potentially decreased median length of hospital stay. However, the current study demonstrated a higher conversion rate of minimally invasive gastrectomies in the acute setting (23% versus 0.9% [12], 3.5% [11] and 10% [10] in the elective setting), as well as a potentially increased percentage of patients that underwent a reintervention after minimally invasive gastrectomy (23% versus 14% in the acute setting and 0.4% versus 0.4% [11], 1.2% versus 1.5% [12] and 17% versus 16% [10] in the elective setting for minimally invasive gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy, respectively). Unfortunately, no clear explanation for this difference could be deduced from the causes for the re-interventions as available in the data.

In order to correctly interpret the current results, it must be noted that esophagogastric cancer surgery has been centralized since 2011 in the Netherlands. This is one of the main reasons that 84% of the elective esophagectomies and 40% of the elective gastrectomies are performed by minimally invasive techniques in the recent years [6, 9]. A similar increase has been seen for the use of minimally invasive techniques in the acute setting. Most surgeons in the Netherlands implemented these techniques after participating in a hands-on course on minimally invasive esophagectomy and gastrectomy, followed by several cases with an experienced surgeon present. The influence of centralization and learning curves on postoperative outcomes also seem to be important in for esophagogastric surgery in the acute setting, as demonstrated by a recently published study from England [16]. High-volume cancer centers and surgeons are more experienced in managing patients following esophagectomy and gastrectomy, and have the appropriate infrastructure available [16]. As such, they might be better equipped to deliver consistent levels of high-quality outcomes for minimally invasive surgery in the acute setting as well which might explain the comparable outcomes for minimally invasive and open surgery in the current study.

Overall, acute surgical interventions for upper gastrointestinal malignancies are rare, accounting for only 2% of all surgical interventions for upper gastrointestinal malignancies in the Netherlands. This especially applies for surgical interventions for esophageal cancer, occurring approximately once yearly in a country with an incidence of approximately 2500 new esophageal cancer cases per year [17]. Interestingly, most patients who underwent an acute surgical intervention had prior histological confirmation of their cancer diagnosis, indicating that patients generally did not present with an acute symptom of an unknown malignancy. The majority of the gastric cancer cases had a cause for acute intervention other than bleeding or perforation. As the DUCA registry only registers the indication for acute intervention in 3 prespecified categories (bleeding, perforation and other), the frequency of obstruction as another important indication for acute surgical interventions in gastric cancer could not be researched. However, in patients with an obstruction, a gastroenterostomy or distal gastrectomy might have been more frequently performed. When the surgical procedures of patients without a specified reason for the surgical intervention are explored in more detail, it might indeed be that obstruction accounts for a large share of the not specified indications, as 30% of them underwent a gastroenterostomy (21/71) and 44% underwent a partial gastrectomy (31/71) (data not shown).

The population-based design with virtually complete inclusion of all patients in the Netherlands is a significant strength of the study, along with the prospective data collection and detailed information on strictly defined postoperative outcomes. However, there are some limitations of the current study that need to be addressed. First, the small numbers of patients in all groups precluded a direct comparison between minimally invasive and open surgery correcting for bias. This prevents firm conclusions to be drawn regarding the potentially observed benefits of minimally invasive compared to open surgery in the acute setting (e.g., the decreased median length of hospital stay, higher observed percentage of radical resections and increased median lymph node yield), as well as regarding the potential disadvantages of minimally invasive surgery (e.g., the increased percentage of re-interventions after minimally invasive gastrectomy compared to open gastrectomy). Second, the introduction of minimally invasive surgery for upper gastrointestinal malignancies occurred simultaneously with centralization of cancer care and the introduction of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs in the Netherlands. It has been shown that centralization of surgery is associated with reduced complications and improved long-term survival [18–21] and that the use of ERAS programs protocols can reduce the length of hospital stay [22, 23]. As such, the observed outcomes in this study for both minimally invasive as open surgery are probably influenced by these factors. It must be further acknowledged as a limitation that, due to the privacy restrictions of the national database, individual hospital related factors such as postoperative management protocols and background experience in minimally invasive surgery might have influenced the results but were not available. This also applies to more detailed information regarding the reasons for surgical intervention, such as iatrogenic versus spontaneous perforations and the severity of the bleeding. Lastly, no long-term survival data are available for the patients in the DUCA registry.

Future research regarding this topic would benefit from an even larger cohort study that would allow for statistical analyses corrected for bias to compare minimally invasive surgery and open surgery for esophagogastric cancer in the acute setting. However, considering the rarity of these events, larger case series are probably difficult to find.

In conclusion, this nationwide cohort study demonstrates that acute surgical interventions for esophageal and gastric cancer are rare. For gastric cancer, minimally invasive surgery appears to be feasible and safe in the acute setting with at least comparable postoperative clinical and short-term oncological outcomes compared to open surgery, but a relatively high conversion rate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all surgeons, registrars, physician assistants and administrative nurses for collecting the data and the Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit (DUCA) for supplying the data for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosures

Jelle P. Ruurda and Richard van Hillegersberg are proctoring surgeons for Intuitive Surgical Inc. and train other surgeons in robot-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy. Alicia S. Borggreve and B. Feike Kingma have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Haverkamp L, Seesing MF, Ruurda JP, Boone J, Hillegersberg R. Worldwide trends in surgical techniques in the treatment of esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Dis esophagus. 2017;30(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/dote.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenkman HJ, Haverkamp L, Ruurda JP, van Hillegersberg R. Worldwide practice in gastric cancer surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(15):4041–4048. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i15.4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biere SS, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Maas KW, et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Der Sluis PC, Van Der Horst S, May AM, et al. Robot-assisted minimally invasive thoracolaparoscopic esophagectomy versus open transthoracic esophagectomy for resectable esophageal cancer a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sihag S, Kosinski AS, Gaissert HA, Wright CD, Schipper PH. Minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a comparison of early surgical outcomes From The Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(4):1281–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seesing MFJ, Gisbertz SS, Goense L, et al. A propensity score matched analysis of open versus minimally invasive transthoracic esophagectomy in the Netherlands. Ann Surg. 2017;266(5):839–846. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi H, Miyata H, Ozawa S, et al. Comparison of short-term outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal cancer using a nationwide database in Japan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(7):1821–1827. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Faiz O, Hanna GB. Short-term outcomes following open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer in England: a population-based national study. Ann Surg. 2012;255(2):197–203. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823e39fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenkman HJF, Ruurda JP, Verhoeven RHA, van Hillegersberg R. Safety and feasibility of minimally invasive gastrectomy during the early introduction in the Netherlands: short-term oncological outcomes comparable to open gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(5):853–860. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0695-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenkman HJF, Gisbertz SS, Slaman AE, et al. Postoperative outcomes of minimally invasive gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy during the early introduction of minimally invasive gastrectomy in The Netherlands: a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(5):831–838. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, et al. Short-term surgical outcomes from a phase III study of laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA/IB gastric cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0912. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(4):699–708. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim W, Kim H-H, Han S-U, et al. Decreased morbidity of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy compared with open distal gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busweiler LAD, Wijnhoven BPL, van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Early outcomes from the Dutch upper gastrointestinal cancer audit. Br J Surg. 2016;103(13):1855–1863. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National guideline esophageal cancer (version 3.1) (2015) https://www.oncoline.nl/oesofaguscarcinoom (accessed 21 Mar 2018)

- 15.National guideline gastric cancer (version 2.2) (2017) https://www.oncoline.nl/maagcarcinoom (accessed 21 Mar 2018)

- 16.Markar SR, Mackenzie H, Wiggins T, et al. Influence of national centralization of oesophagogastric cancer on management and clinical outcome from emergency upper gastrointestinal conditions. Br J Surg. 2018;105(1):113–120. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland (IKNL). Cijfers over kanker (2018) https://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/ (accessed 11 Dec 2018)

- 18.Coupland VH, Lagergren J, Lüchtenborg M, et al. Hospital volume, proportion resected and mortality from oesophageal and gastric cancer: a population-based study in England, 2004–2008. Gut. 2013;62(7):961–966. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derogar M, Sadr-Azodi O, Johar A, Lagergren P, Lagergren J. Hospital and surgeon volume in relation to survival after esophageal cancer surgery in a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):551–557. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brusselaers N, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Hospital and surgeon volume in relation to long-term survival after oesophagectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2014;63(9):1393–1400. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dikken JL, Dassen AE, Lemmens VEP, et al. Effect of hospital volume on postoperative mortality and survival after oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery in the Netherlands between 1989 and 2009. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(7):1004–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Findlay JM, Gillies RS, Millo J, Sgromo B, Marshall RE, Maynard ND. Enhanced recovery for esophagectomy: a systematic review and evidence-based guidelines. Ann Surg. 2014;259(3):413–431. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markar SR, Schmidt H, Kunz S, Bodnar A, Hubka M, Low DE. Evolution of standardized clinical pathways: refining multidisciplinary care and process to improve outcomes of the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(7):1238–1246. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]