Abstract

In addition to nucleosomes, chromatin contains non-histone chromatin-associated proteins, of which the high-mobility group proteins are the most abundant. Chromatin-mediated regulation of transcription involves DNA methylation and histone modifications. However, the order of events and the precise function of high-mobility group proteins during transcription initiation remain unclear. Here we show that high-mobility group AT-hook 2 protein (HMGA2) induces DNA nicks at the transcription start site, which are required by the histone chaperone FACT complex to incorporate nucleosomes containing the histone variant H2A.X. Further, phosphorylation of H2A.X at S139 (γ-H2AX) is required for repair-mediated DNA demethylation and transcription activation. The relevance of these findings is demonstrated within the context of TGFB1 signaling and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, suggesting therapies against this lethal disease. Our data support the concept that chromatin opening during transcriptional initiation involves intermediates with DNA breaks that subsequently require DNA repair mechanisms to ensure genome integrity.

Subject terms: Chromatin, Chromatin structure, Histone post-translational modifications, Histone variants, Epigenetics

The order of DNA methylation and histone modifications during transcription remained unclear. Here the authors show that HMGA2 induces DNA nicks at TGFB1-responsive genes, promoting nucleosome incorporation containing γ-H2AX, which is required for repair-mediated DNA demethylation and transcription.

Introduction

In the eukaryotic cell nucleus, chromatin is the physiological template of all DNA-dependent processes including transcription. The structural and functional units of chromatin are the nucleosomes, each one consisting of ~147 bp of genomic DNA wrapped around a core histone octamer, which in turn is built of two H2A–H2B dimers and one (H3–H4)2 tetramer1,2. In addition to canonical histones (H1, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4), there are so called histone variants for all histones except for H4. Histone variants differ from the canonical histones in their amino acid sequence and have specific and fundamental functions that cannot be performed by canonical histones. The canonical histone H2A has a large number of variants, each with defined biochemical and functional properties3,4. Here we focus on the histone variant H2AFX (commonly known as H2AX, further referred to as H2A.X), which represents about 2–25% of the cellular H2A pool in mammals5. Phosphorylated H2A.X at serine 139 (H2A.XS139ph; commonly known as γ-H2AX, further referred to as pH2A.X) is used as a marker for DNA double-strand breaks6. However, accumulating evidence suggests additional functions of pH2A.X7–10. The histone chaperone FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription) is a heterodimeric complex, consisting of SUPT16 and SSRP1 (Spt16 and Pob3 in yeast) that is responsible for the deposition of H2A/H2B-dimers onto DNA11,12. The FACT complex mainly interacts with H2B mediating the deposition of H2A/H2B-dimers containing different H2A variants13. Thus, the deposition of H2A.X into chromatin seems to be mediated by the FACT complex14.

In addition to nucleosomes, chromatin contains non-histone chromatin-associated proteins, of which the high-mobility group (HMG) proteins are the most abundant. Although HMG proteins do not possess intrinsic transcriptional activity, they are called architectural transcription factors because they modulate the transcription of their target genes by altering the chromatin structure at the promoter and/or enhancers15. Here we will focus on HMG AT-hook 2 protein (HMGA2), a member of the HMGA family that mediates transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1, commonly known as TGFβ1) signaling16. We have previously shown that HMGA2-induced transcription requires phosphorylation of H2A.X at S139, which in turn is mediated by the protein kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)10. Furthermore, we demonstrated the biological relevance of this mechanism of transcriptional initiation within the context of TGFB1 signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Interestingly, TGFB signaling has been reported to induce active DNA demethylation with the involvement of thymidine DNA glycosylase (TDG)17. Active DNA demethylation also requires GADD45A (growth arrest and DNA damage protein 45 alpha) and TET1 (ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1), which sequentially oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC)18,19 and are cleared through DNA repair mechanisms. In line with these ideas, classical DNA-repair complexes have been linked to DNA demethylation and transcriptional activation20,21. On the other hand, DNA double-strand breaks induce ectopic transcription that is essential for repair, supporting a tight mechanistic correlation between transcription, DNA damage, and repair22.

TGFB1 signaling and EMT are both playing a crucial role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). IPF is the most common interstitial lung disease showing a prevalence of 20 new cases per 100,000 persons per year23,24. A central event in IPF is the abnormal proliferation and migration of fibroblasts in the alveolar compartment in response to lung injury. IPF patients die within 2 years after diagnosis mostly due to respiratory failure. Current treatments against IPF aim to ameliorate patient symptoms and to delay disease progression25. Unfortunately, therapies targeting the causes of or reverting IPF have not yet been developed. Here, we demonstrate that inhibition of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis reduces fibrotic hallmarks in vitro using primary human lung fibroblast (hLF) and ex vivo using human precision-cut lung slices (hPCLS), both from control and IPF patients. Our study supports the development of therapeutic approaches against IPF using FACT inhibition.

Results

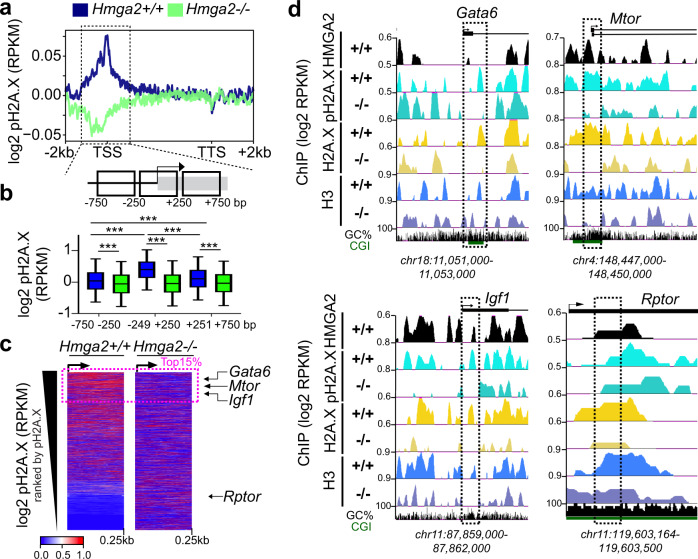

HMGA2 is required for pH2A.X deposition at transcription start sites

We have previously reported that HMGA2-mediated transcription requires phosphorylation of the histone variant H2A.X at S139, which in turn is catalyzed by the protein kinase ATM10. To further dissect this mechanism of transcription initiation, we decided first to determine the effect of Hmga2-knockout (KO) on genome wide levels of pH2A.X. We performed next generation sequencing (NGS) after chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1a) using pH2A.X-specific antibodies and chromatin isolated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) from wild-type (WT = Hmga2 + /+) and Hmga2-deficient (Hmga2-KO = Hmga2−/−)26 embryos. The analysis of these ChIP-seq results using the UCSC Known Genes dataset27 revealed that pH2A.X is specifically enriched at transcription start sites (TSS) of genes in an Hmga2-dependent manner (Fig. 1a), since Hmga2-KO significantly reduced pH2A.X levels. A zoom into the −750 to +750 base pair (bp) region relative to the TSS (Fig. 1b) revealed that pH2A.X levels significantly peaked ( = 0.396; n = 9522; P < 2.2E-16) at the TSS (−250 to +250 bp) in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Further, the genes were ranked based on pH2A.X levels at the TSS (Source Data file 04) and the results were visualized as heat maps (Fig. 1c). From the top 15% of the genes with high pH2A.X levels at TSS (further referred as top 15% candidates; n = 9522), we selected Gata6 (GATA binding protein 6), Mtor (mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase) and Igf1 (insulin like growth factor 1) for further single gene analysis. Explanatory for these gene selection, we have previously reported Gata6 as direct target gene of HMGA210,28, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway enrichment based analysis of the top 15% candidates showed significant enrichment of genes related to the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. 1b), HMGA2 has been related to the insulin signaling pathway29,30. In addition, Rptor (regulatory associated protein of MTOR complex 1) is outside of the top 15% candidates (Fig. 1c) and was selected as negative control. Visualization of the selected genes using the UCSC genome browser confirmed the reduction of pH2A.X at specific regions close to TSS in Hmga2−/− MEF when compared to Hmga2 + /+ MEF (Fig. 1d, top) except in the negative control Rptor. Similar results were obtained after ChIP-seq using H2A.X and H3 antibodies (Fig. 1d, bottom), the last one frequently used for monitoring nucleosome position. Promoter analysis of Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor by ChIP using pH2A.X-, H2A.X-, H3- and HMGA2-specific antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d) confirmed the ChIP-seq data. These findings suggest that the first nucleosome relative to the TSS of the top 15% candidates contains pH2A.X and Hmga2 is required for correct positioning of this first nucleosome.

Fig. 1. HMGA2 is required for pH2A.X deposition at TSS.

a Aggregate plot for pH2A.X enrichment within the gene body ±2 kb of UCSC Known Genes in Hmga2+/+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. ChIP-seq reads were normalized using reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) measure and are represented as log2 enrichment over their corresponding inputs. TSS, transcription start site; TTS, transcription termination site. Dotted square, ±750 bp region around the TSS. b Top, schematic representation of the genomic region highlighted in a. Bottom, box plot of pH2A.X enrichment in the genomic regions showed as squares at the top in Hmga2+/+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. RPKM of the pH2A.X ChIP-seq were binned within each of these genomic regions and represented as log2. Box plots indicate median (middle line), 25th, 75th percentile (box) and 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers); n = 9522 genes enriched with pH2A.X; asterisks P-values after two-tailed Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, ***P ≤ 0.001. c Heat map for pH2A.X enrichment at the TSS + 0.25 kb of UCSC Known Genes in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. Genes were ranked by pH2A.X enrichment in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Doted square, the top 15% ranked genes, as well as Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor were selected for further analysis. d Visualization of selected HMGA2 target genes using UCSC Genome Browser showing HMGA2 (black), pH2A.X (turquoise), H2A.X (yellow) and H3 (blue) enrichment in Hmga2+/+ and −/− MEF. ChIP-seq reads were normalized using RPKM measure and are represented as log2 enrichment over their corresponding inputs. Images show the indicated gene loci with their genomic coordinates. Arrows, direction of the genes; black boxes, exons; dotted squares, regions selected for single gene analysis. See also Supplementary Fig. 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 04.

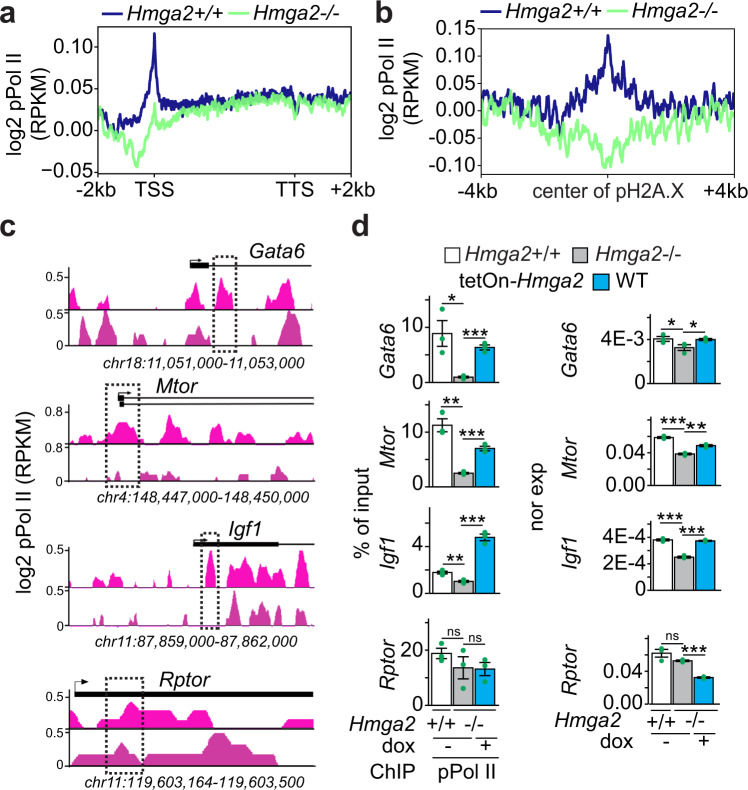

Position of the first nucleosome containing pH2A.X correlates with RNA polymerase II and the basal transcription activity of genes

Phosphorylation of specific amino acids in the C-terminal domain of the large subunit of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) determines its interaction with specific factors, thereby regulating the transcription cycle consisting of initiation, elongation and termination31. To monitor transcription initiation, ChIP-seq was performed using antibodies specific for transcription initiating S5 phosphorylated Pol II (further referred to as pPol II) and chromatin isolated from Hmga2+/+ and Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Analysis of the ChIP-seq results using the UCSC Known Genes dataset revealed that pPol II was enriched at TSS in Hmga2-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). In addition, we observed that pPol II enrichment coincides with pH2A.X peaks at TSS (Fig. 2b) also in an Hmga2-dependent manner. Visualization of Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 using the UCSC genome browser (Fig. 2c) and ChIP analysis of their promoters (Fig. 2d, left) confirmed the reduction of pPol II at specific regions close to TSS in Hmga2−/− MEF when compared to Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Furthermore, the reduced pPol II levels after Hmga2-KO correlated with the reduced expression of the analyzed genes as shown by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR, Fig. 2d, right). These effects were not observed in the negative control Rptor. Moreover, Hmga2 overexpression in Hmga2−/− MEF reverted the observed effects (Fig. 2d), thereby demonstrating the specificity of the changes caused by Hmga2-KO.

Fig. 2. Position of transcription initiating S5 phosphorylated RNA polymerase II at the TSS is Hmga2-dependent.

a, b Aggregate plots for phosphorylated serine 5 RNA polymerase II (pPol II) enrichment within the gene body ±2 kb of UCSC Known Genes (a) and in a ± 4 kb region respective to pH2A.X peaks (b) in Hmga2+/+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. ChIP-seq reads were normalized using reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) measure and are represented as log2 enrichment over their corresponding inputs. TSS, transcription start site; TTS, transcription termination site. c Visualization of selected HMGA2 target genes using UCSC Genome Browser showing pPol II enrichment in Hmga2 + /+ and −/− MEF. ChIP-seq reads were normalized using RPKM measure and are represented as log2 enrichment over their corresponding inputs. Images represent the indicated gene loci with their genomic coordinates. Arrows, direction of the genes; black boxes, exons; dotted squares, regions selected for single gene analysis. d Analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes. Left, ChIP of Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor after pPol II immunoprecipitation in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. Right, qRT-PCR-based, Tuba1a-normalized expression analysis under the same conditions. Bar plots presenting data as means; error bars, s.e.m (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after two-tailed t-test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05. See also Supplementary Figs. 1–2 . Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 04.

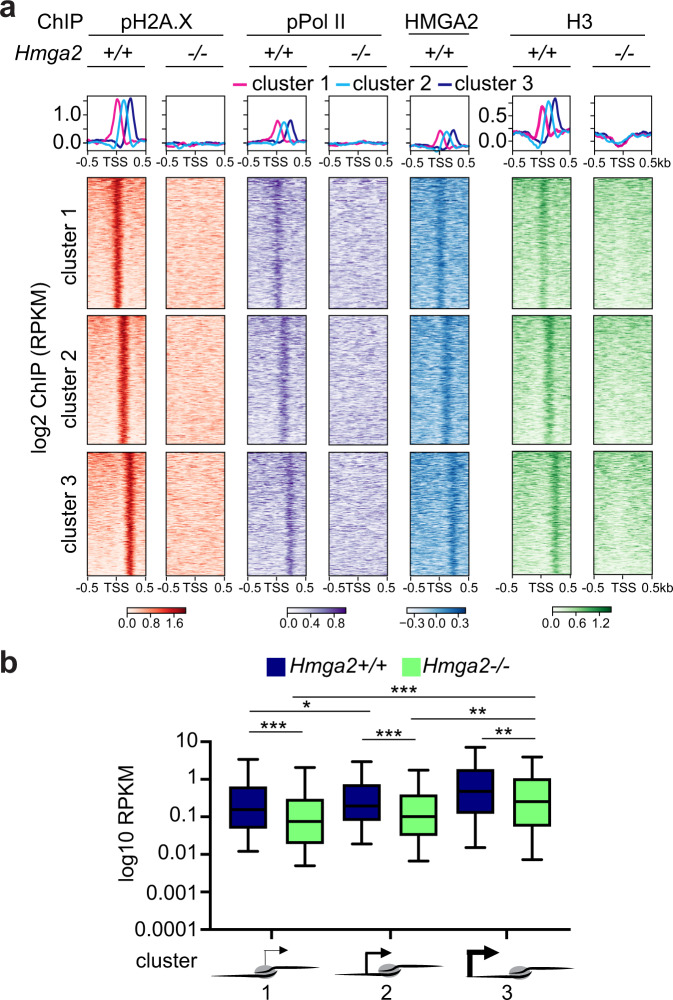

Further analysis of the ChIP-seq data by k-means clustering32 revealed three clusters in the top 15% candidates (Fig. 3a). Cluster 1 (n = 3266) showed pPol II, pH2A.X, HMGA2 and H3 enrichment directly at the TSS (top), while clusters 2 (n = 3208) and 3 (n = 3075) showed enrichment of these proteins 125 bp and 250 bp 3′ of the TSS, respectively (middle and bottom). Remarkably, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) based expression analysis in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 3b) revealed that the genes in the three clusters have different basal transcription activities, whereby cluster 1 has the lowest (x̄ = 0.6201), cluster 2 the middle (x̄ = 0.6979) and cluster 3 the highest (x̄ = 1.56) basal transcription activity in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Hmga2-KO significantly reduced the basal transcription activity in all three clusters, to 0.325 (P = 4.72E-5) in cluster 1, 0.375 (P = 1E-4) in cluster 2 and 0.867 (P = 2.47E-3) in cluster 3. Our results demonstrate a correlation between the basal transcription activity and the position of pPol II, pH2A.X, HMGA2 and H3 relative to TSS. Interestingly, the observed Hmga2-dependent effects are specific for the top 15% candidates (n = 9522), which have relatively low pPol II levels and basal transcription activities (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c).

Fig. 3. Position of first nucleosome containing pH2A.X correlates with RNA polymerase II and basal transcription activity in Hmga2-dependent manner.

a Aggregate plots (top) and heat maps (bottom) for pPol II, pH2A.X, HMGA2 and H3 enrichment at the TSS ± ≥ kb of the top 15% candidates in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. Three clusters were generated using k-means algorithm. Genes were sorted based on the enrichment of pH2A.X in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. b Box plot representing the basal transcription activity (as log2 RPKM) of genes in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. The genes were sorted in three groups based on the position of the first pH2A.X-containing nucleosome 5´ to the TSS. Box plots indicate median (middle line), 25th, 75th percentile (box) and 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers); n = 154 genes in position cluster 1; n = 132 genes in position cluster 2; n = 134 genes in position cluster 3; asterisks, P-values after one-tailed Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05. See also Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 04.

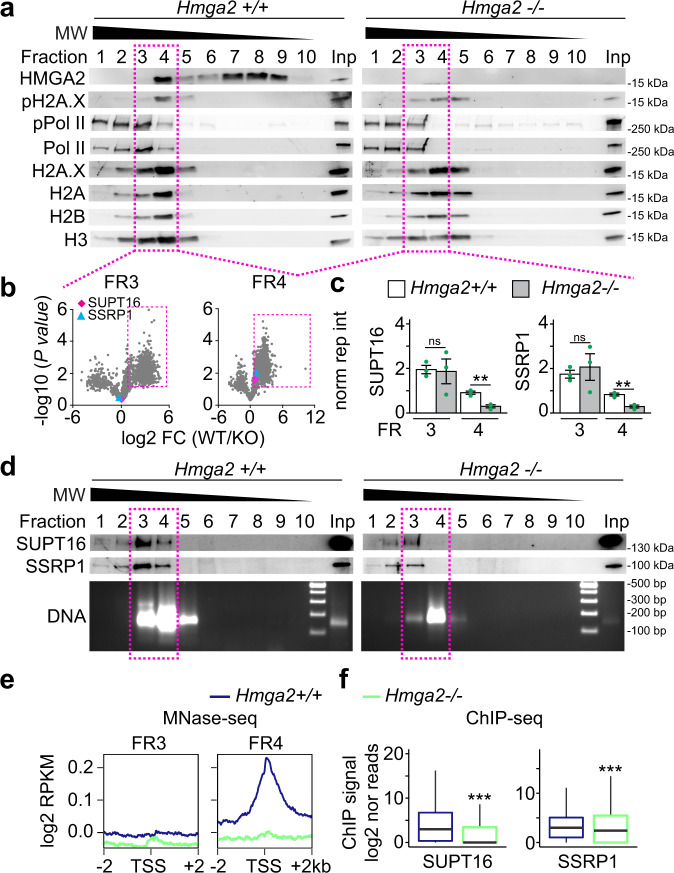

HMGA2 is required for enrichment of the FACT complex at TSS

To gain insights into the HMGA2, ATM, and pH2A.X transcriptional network10, native chromatin preparations from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF were digested with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) and subsequently fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation (SGU) (Fig. 4a–e and Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). From the obtained fractions, the proteins were extracted and analyzed either by western blot (WB; Fig. 4a, d, top), by densitometry analysis of WB (Supplementary Fig. 3b), or by high-resolution mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach (Fig. 4b–c and Source Data file 04), while the DNA was also isolated and analyzed either by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4d, bottom), or by DNA sequencing (MNase-seq, Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). In Hmga2 + /+ MEF (Fig. 4a, left and Supplementary Fig. 3b), WB of the obtained fractions showed that HMGA2 sedimented in fractions 4 to 9, whereas pPol II and histones mainly sedimented in fractions 1 to 4, where protein complexes of higher molecular weight (MW) are expected. Interestingly, the histone variant H2A.X and its post-translationally modified form pH2A.X showed a similar sedimentation pattern as the core histones. However, pH2A.X sedimentation in fraction 4 was more pronounced. In Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 4a, right and Supplementary Fig. 3b) the levels of pH2A.X were reduced and distributed in fractions 3 to 5. The reducing effect of Hmga2-KO on pH2A.X levels was confirmed by immunostaining in MEF (Supplementary Fig. 4c–d). The subsequent analysis was focused on fractions 3 and 4, because fraction 4 contained all proteins monitored by WB in Hmga2 + /+ MEF, whereas in fraction 3 levels of HMGA2 and pH2A.X were significantly reduced. We analyzed these two fractions by high-resolution mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach and identified proteins that were more than 1.65-fold significantly enriched in Hmga2 + /+ MEF when compared to Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 4b; Source Data file 04; n = 1215 and P < 0.05 in fraction 3; n = 1729 and P < 0.05 in fraction 4). A closer look on the proteins enriched in fractions 3 and 4 of Hmga2 + /+ MEF revealed the presence of both components of the FACT complex, SUPT16 and SSRP1 (Fig. 4b), as well as proteins related to transcription regulation and nucleotide excision repair (NER; Supplementary Fig. 3c). Interestingly, Hmga2-KO significantly reduced the levels of SUPT16 (from 0.909 to 0.298; n = 3; P = 3.5E-3) and SSRP1 (from 0.831 to 0.290; n = 3; P = 3.9E-3) in fraction 4 without significantly affecting their levels in fraction 3 (Fig. 4c). WB of SGU fractions using SUPT16- or SSRP1-specific antibodies (Fig. 4d, top) and the corresponding densitometry analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3b) show a reduction of both components of the FACT complex in fractions 3 and 4, being more pronounced in fraction 4. Further, we isolated and analyzed by electrophoresis the DNA from the SGU fractions and found DNA fragments with a length profile of 100–300 bp that mainly sedimented in fractions 3 to 5 of both Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF. The length profile of DNA fragments supports the majority presence of mono- and di-nucleosomes in the native chromatin preparations that were fractionated by SGU. Focusing again on fraction 3 and 4, MNase-seq was performed and reads between 100 to 200 bp were selected for downstream analysis (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Using the UCSC Known Genes as reference dataset, we found that in fraction 4 the sequencing reads were enriched with TSS in an Hmga2-dependent manner (Fig. 4e), since this enrichment was abolished after Hmga2-KO. In fraction 3, we did not detect TSS enrichment of the sequencing reads. Our results indicate that the native chromatin in fraction 4 contains mono- and di-nucleosomes (Supplementary Fig. 4b), which are enriched with TSS, HMGA2, pH2A.X and pPol II in WT MEF. To link the results obtained by MNase-seq and mass spectrometry after fractionation by SGU, we performed ChIP-seq using SUPT16- and SSRP1-specific antibodies and chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 4e). Confirming the results in fraction 4, an accumulation of both components of the FACT complex was detected at TSS in Hmga2 + /+ MEF, whereas Hmga2-KO reduced the levels of SUPT16 and SSRP1 at TSS. In summary, these results demonstrate that HMGA2 is required for recruitment of the FACT complex to TSS.

Fig. 4. HMGA2 is required for enrichment of the FACT complex at TSS.

a–e Native chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ and −/− MEF was digested with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) and fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation (SGU). a The obtained fractions were analyzed by WB using the indicated antibodies. Representative images from three independent experiments. MW, molecular weight, kDa, kilo Dalton. Inp, input represents 0.5% of the material used for SGU. Square, fractions selected for further analysis. b Mass spectrometry analysis of proteins in fractions 3 and 4. Volcano plot representing the significance (−log10 P-values after one-tailed t-test) vs. intensity fold change between Hmga2 + /+ and −/− MEF (log2 of means intensity ratios from three independent experiments). Square, proteins with log2 fold change >1.65. Diamond, SUPT16; triangle, SSRP1. c Bar plots showing normalized reporter intensity of SUPT16 (left) and SSRP1 (right) in fractions 3 and 4 of the SGU in a. Data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after two-tailed t-Test, **P ≤ 0.01; ns, non-significant. d Top, WB analysis as in a using antibodies specific for components of the FACT complex. Bottom, DNA was isolated from the fractions obtained by SGU in A and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Representative images from three independent experiments. Square, fractions selected for MNase-seq. e MNase-seq of fractions 3 and 4 of the SGU in a. Aggregate plots representing the enrichment over input (as log2 RPKM) of genomic sequences relative to the TSS ± 2 kb. f Box plots of ChIP-seq-based SUPT16 (left) and SSRP1 (right) enrichment analysis within the TSS + 0.5 kb of the top 15% candidates in Hmga2 + /+ and −/− MEF. Values are represented as log2 of mapped reads that were normalized to the total counts and the input was subtracted. Box plots indicate median (middle line), 25th, 75th percentile (box) and 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers); n = 9522 genes enriched with pH2A.X; asterisks, P-values after two-tailed Mann–Whitney test, ***P ≤ 0.001. See also Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 02.

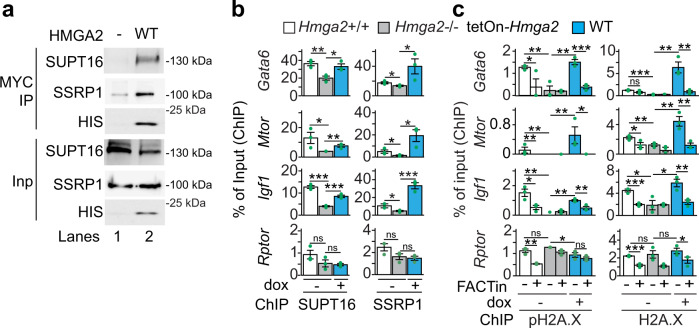

HMGA2-FACT interaction is required for pH2A.X deposition

The results in Fig. 4a–f suggest an interaction between HMGA2 and the FACT complex. In addition, we found in our previously published mass spectrometry based HMGA2 interactome10 that HMGA2 precipitated SUPT16 and SSRP1 (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Indeed, the interaction of HMGA2 with both components of the FACT complex was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay using nuclear protein extracts from MEF after overexpression of HMGA2 tagged C-terminally with MYC and HIS (HMGA2-MYC-HIS; Fig. 5a). To further characterize the HMGA2-FACT interaction, nuclear extracts from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF were fractionated into chromatin-bound and nucleoplasm fractions (Supplementary Fig. 5a). WB of these fractions showed that HMGA2 was exclusively bound to chromatin, whereas SUPT16 and SSRP1 were present in both sub-nuclear fractions. However, higher levels of both FACT components were detected in the chromatin-bound fraction of Hmga2 + /+ MEF as compared to the nucleoplasm. Interestingly, Hmga2-KO reverted the distribution of SUPT16 and SSRP1 between these two sub-nuclear fractions, thereby supporting that Hmga2 is required for tethering the FACT complex to chromatin. These results were confirmed by ChIP of Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor (Fig. 5b) using SUPT16- and SSRP1-specific antibodies and chromatin isolated from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF that were stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible expression construct (tetOn) either empty (−; negative control) or containing the cDNA of WT HMGA2-MYC-HIS. Doxycycline treatment of these stably transfected MEF induced the expression of WT HMGA2-MYC-HIS (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Hmga2-KO reduced the levels of SUPT16 and SSRP1 in the promoters of the selected HMGA2 target genes (Fig. 5b), while doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2-MYC-HIS in Hmga2−/− MEF reconstituted the levels of both FACT components, thereby demonstrating the specificity of the effects caused by Hmga2-KO. These effects were not observed in the negative control Rptor.

Fig. 5. HMGA2 -FACT interaction is required for pH2A.X deposition.

a Western blot using the indicated antibodies after co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay using nuclear protein extracts from Hmga2−/− MEF that were non-transfected (−) or stably transfected with Hmga2-myc-his (WT) and magnetic beads coated with MYC-specific antibodies. Representative images from three independent experiments. Input, 5% of IP starting material. b, c ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from Hmga2 + /+, Hmga2−/− MEF, as well as Hmga2−/− MEF that were stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible expression construct (tetOn) for WT Hmga2-myc-his. MEF were treated with doxycycline and FACT inhibitor (FACTin; CBLC000 trifluoroacetate) as indicated. In all bar plots, data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after one-tailed t-Test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, non-significant. See also Supplementary Fig. 5. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 02.

To demonstrate the causal involvement of the FACT complex in context of HMGA2-mediated chromatin rearrangements, we analyzed the levels of pH2A.X and H2A.X at the Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor promoters by ChIP using chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ MEF and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF that were treated with DMSO (control) or a FACT inhibitor (FACTin; CBLC000 trifluoroacetate)33 and doxycycline as indicated (Fig. 5c). FACTin treatment induces negative supercoiling and the formation of left-handed Z-DNA, which is recognized by the FACT subunit SSRP134. Increasing doses of FACTin resulted in chromatin trapping of SUPT16 and SSRP1 (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d)35. In addition, FACT inhibition significantly reduced pH2A.X and H2A.X levels specifically at the promoters of the selected HMGA2 target genes, confirming that the FACT complex is required for proper H2A.X deposition (Fig. 5c, left). Further, Hmga2-KO also reduced pH2A.X and H2A.X levels at the same promoters (middle), while doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2-MYC-HIS in Hmga2−/− MEF reconstituted the pH2A.X and H2A.X levels (right), thereby confirming the results presented in Figs. 1 and 5b. Remarkably, FACT inhibition counteracted the reconstituting effect mediated by doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2-MYC-HIS, showing the causal involvement of the FACT complex in the function of HMGA2. In summary, these results demonstrate that the FACT complex is required for HMGA2 function and consequently also for proper pH2A.X levels at the promoters of the HMGA2 target genes.

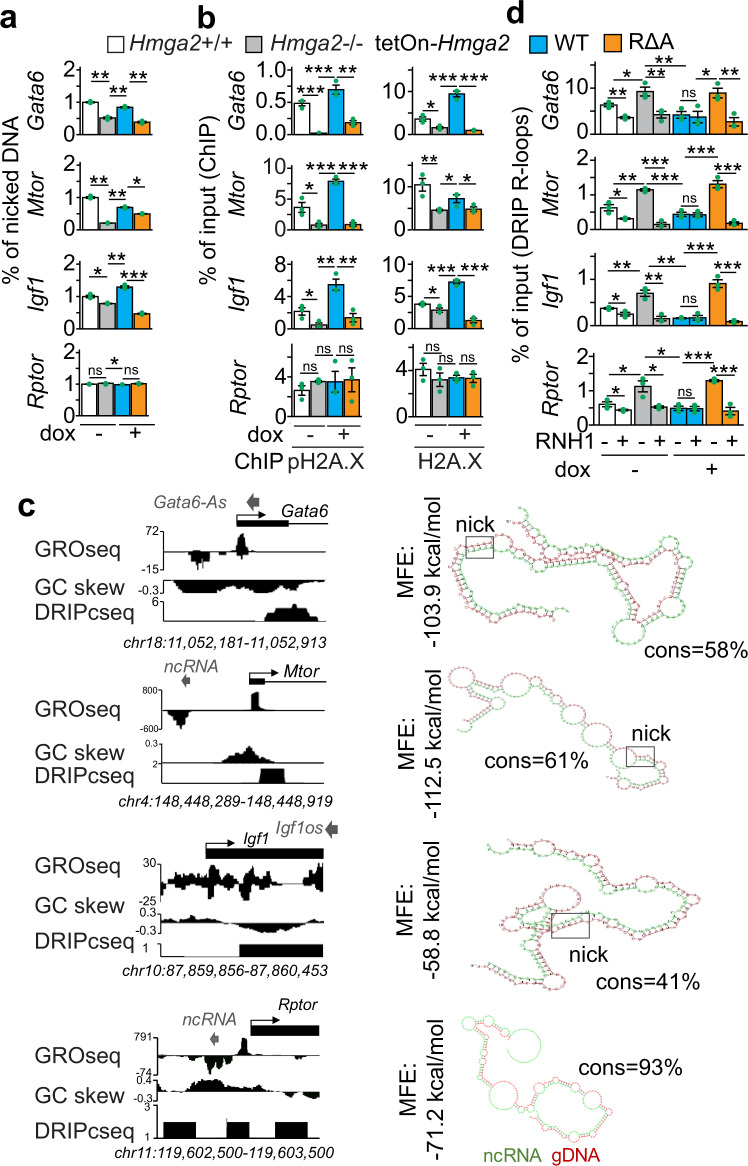

After confirming the loss of lyase activity in RΔA HMGA2-MYC-HIS (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d), single-strand DNA breaks (DNA nicks) at the Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor promoters were monitored using genomic DNA from Hmga2 + /+ MEF and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF that were non-treated (−) or treated with doxycycline (Fig. 6a). We detected DNA nicks at the analyzed promoters in Hmga2 + /+ MEF, whose levels were reduced upon Hmga2-KO specifically at the promoter of the selected HMGA2 target genes. Interestingly, inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF reconstituted the levels of DNA nicks, whereas RΔA HMGA2 did not rescue the effect induced by Hmga2-KO, thereby confirming that HMGA2 lyase activity is required for the DNA nicks detected at the promoters of HMGA2 target genes. Further, we decided to demonstrate the requirement of the lyase activity for the function of HMGA2. Thus, the levels of pH2A.X and H2A.X at the Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor promoters were analyzed by ChIP using chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 6b). Confirming the results in Figs. 1 and 5c, Hmga2-KO reduced pH2A.X and H2A.X levels specifically at the promoter of the selected HMGA2 target genes. In addition, doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− cells reconstituted the levels of pH2A.X and H2A.X, demonstrating the specificity of the effect observed after Hmga2-KO. However, doxycycline-inducible expression of RΔA HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF did not rescue the effect induced by Hmga2-KO. Although the mutations inducing the loss of the lyase activity did not affect the HMGA2-FACT complex interaction (Supplementary Fig. 6e), these results show that the lyase activity is required for proper pH2A.X and H2A.X levels at the promoter of the selected HMGA2 target genes.

Fig. 6. HMGA2-lyase activity is required for pH2A.X deposition and solving of R-loops.

a Analysis of single-strand DNA breaks at promoters of selected HMGA2 target genes using genomic DNA from Hmga2 + /+, Hmga2−/− MEF, as well as Hmga2−/− MEF that were stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible expression construct (tetOn) either for WT Hmga2-myc-his or the lyase-deficient mutant RΔA Hmga2-myc-his. MEF were treated with doxycycline as indicated. b ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from MEF as in a. c Left, Genome-browser visualization of selected HMGA2 target genes showed nascent RNA (GRO-seq) in WT MEF68, GC-skew and RNA-seq on plus-strand after DNA-RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation (DRIPc-seq) in NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts40. Images represent mapped sequence tag densities relative to the indicated loci. Genomic coordinates are shown at the bottom. Arrow heads, non-coding RNAs in antisense orientation; Arrows, direction of the genes; black boxes, exons. Right, in silico analysis revealed complementary sequences between the identified antisense ncRNA (green) and genomic sequences at the TSS of the corresponding mRNAs (red) with relatively favorable minimum free energy (MFE) and high percentage of complementarity (cons), supporting the formation of DNA-RNA hybrids containing a nucleotide sequence that favors DNA nicks (squares). d Analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes by DNA–RNA immunoprecipitation (DRIP) using the antibody S9.641 and nucleic acids isolated from MEF treated as in a. Prior IP, nucleic acids were digested with RNase H1 (RNH1) as indicated. In all bar plots, data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after two-tailed t-Test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, non-significant. See also Supplementary Figs. 5–7. Source data are provided as a Source Data file 01.

Interestingly, crossing the NONCODE database with our top 15% candidates revealed that 79% of the candidates have annotated noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in close proximity (n = 7535), including Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor (Fig. 6c, left top). Mapping the identified ncRNAs to the murine genome allowed us to identify 2,106 unique ncRNAs (7.4%) that mapped to loci close to promoters controlling the expression of adjacent mRNAs (Supplementary Fig, 7b). From these promoter related ncRNAs36,37 more than half (1401; 67%) were in the antisense strand (as) in divergent (div; 621 ncRNAs) or convergent (con; 780 ncRNAs) orientation36,37 relative to the corresponding promoter and mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). Interestingly, Hmga2-KO significantly reduced the median expression levels of these antisense divergent ncRNAs from 0.085 to 0.067 (P = 0.039; Supplementary Fig. 7e), without significantly affecting the levels of antisense convergent and sense ncRNAs. In silico analysis allowed us to detect putative binding sites of the identified ncRNAs at the TSS of the corresponding mRNAs (Fig. 6c, right) with favorable minimum free energy (MFE < − 55 kcal/mol) and relatively high consensus (cons > 41%;), supporting the formation of DNA-RNA hybrids containing a nucleotide sequence that favors DNA nicks38. In the same genomic regions, we also identified strand asymmetry in the distribution of cytosines and guanines, so called GC skews (Fig. 6c, left middle; Supplementary Fig. 7f, g), that are predisposed to form R-loops, which are three-stranded nucleic acid structures consisting of a DNA-RNA hybrid and the associated non-template single-stranded DNA39. Supporting this hypothesis, published genome-wide sequencing experiments after DNA–RNA immunoprecipitation (DRIP-seq) in NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts40 confirmed the formation of DNA-RNA hybrids in the top 15% candidate genes (n = 9522; Supplementary Fig. 7f, g), including Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor (Fig. 6c, left bottom). This correlated with high amounts of GC skews at their TSS with at least 38.5% of the TSS and downstream region having a GC skew higher than 0.05 (n = 3669). All these observations prompted us to investigate the role of HMGA2 during R-loop formation at the TSS. Thus, we analyzed by DRIP assays the levels of R-loops at the Gata6, Mtor, Igf1 and Rptor promoters using the antibody S9.641 and nucleic acids isolated from Hmga2 + /+ and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 6d). Hmga2-KO increased R-loops levels at the promoters analyzed, whereas doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF reduced R-loop levels back to similar levels as in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Interestingly, doxycycline-inducible expression of RΔA HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF did not rescue the effect induced by Hmga2-KO. In parallel, treatment of the samples before IP with RNase H1 (RNH1), which degrades RNA in DNA-RNA hybrids, reduced the levels of R-loops in all tested conditions, demonstrating the specificity of the antibody S9.641. In summary, these results demonstrate that HMGA2 and its lyase activity are required to solve R-loops at the analyzed promoters, including the negative control Rptor. The fact that we detected R-loops in Rptor (Fig. 6d) without significant changes in the levels of DNA nicks (Fig. 6a) or pH2A.X (Fig. 6b) suggest a different regulatory mechanism for Rptor when compared to the selected Hmga2 target genes.

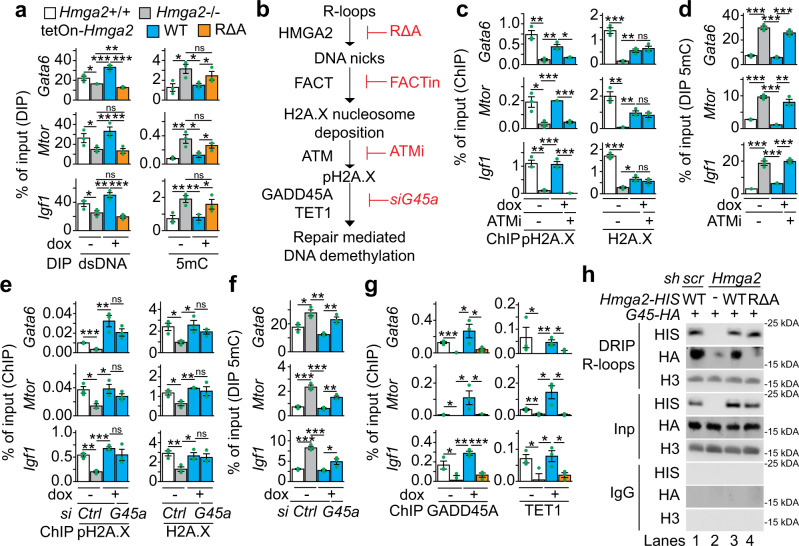

HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis is required to solve R-loops and induce DNA demethylation

The inducible expression of RΔA HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF did not decrease R-loops levels at TSS that were increased after Hmga2-KO (Fig. 6d), supporting that the lyase activity of HMGA2 is required to solve R-loops. To further investigate these results, the levels of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters were analyzed by DNA immunoprecipitation (DIP) assays (Fig. 7a, left). Inversely correlating with the effects on R-loops, Hmga2-KO reduced dsDNA levels at the promoters analyzed. Further, doxycycline-inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF reconstituted dsDNA levels, whereas RΔA HMGA2 failed to rescue the effect induced by Hmga2-KO. These results further support the requirement of HMGA2 and its lyase activity for solving R-loops. Since DNA methylation alters chromatin structure and is associated with R-loop formation18,42, we also analyzed the levels of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters by DIP assays using 5mC-specific antibodies43 (Fig. 7a, right). Correlating with the effects on R-loops, Hmga2-KO increased 5mC levels, which in turn were reduced by inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− cells but not by RΔA HMGA2. These results showed that HMGA2 and its lyase activity are required for proper 5mC levels at the analyzed promoters. In addition, the results using FACTin (Fig. 5c) showed that the FACT complex is required for HMGA2 function and consequently for proper pH2A.X levels at TSS.

Fig. 7. HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis is required to solve R-loops and induce DNA demethylation.

a DNA immunoprecipitation (DIP) based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using antibodies specific for double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and genomic DNA from Hmag2 + /+, Hmag2−/− MEF, as well as Hmga2−/− MEF that were stably transfected with a tetracycline-inducible expression construct (tetOn) for either WT Hmga2-myc-his or the lyase-deficient mutant RΔA Hmga2-myc-his. MEF were treated with doxycycline as indicated. b Schematic representation of the sequential order of events during transcription activation mediated by the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis. c ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from MEF treated as in a. In addition, MEF were treated with ATM inhibitor (ATMi; KU-55933) as indicated. d DIP-based promoter analysis as in a, using 5mC-specific antibodies. In addition, MEF were treated with ATMi as indicated. e ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from MEF treated as in a. In addition, MEF were transfected with control (Ctrl) or Gadd45a-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) as indicated. f DIP-based promoter analysis as in a, using 5mC-specific antibodies. In addition, MEF were transfected with Ctrl or Gadd45a-specific siRNA as indicated. g ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from MEF treated as in a. h WB analysis using antibodies specific for HIS-tag, HA-tag and H3 after DRIP using the antibody S9.641 and chromatin isolated from MLE-12 cells that were stably transfected either with a control (scramble, scr) or an Hmga2-specific short hairpin DNA (sh) construct and transiently transfected with WT Hmga2-myc-his or the lyase-deficient mutant RΔA Hmga2-myc-his and Gadd45-HA as indicated. Representative image from two independent experiments. Input (Inp), 5% of IP starting material; immunoglobulin G (IgG), negative control. In all bar plots, data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after one-tailed t-test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, non-significant. See also Supplementary Fig. 8. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 02.

To demonstrate the sequential order of events of the molecular mechanism proposed here (Fig. 7b), additional experiments were performed (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 8). We first analyzed the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters by DRIP and DIP using nucleic acids isolated from Hmga2 + /+ MEF that were non-treated (-) or treated with FACTin as indicated (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). FACTin treatment in Hmga2 + /+ MEF increased R-loop and 5mC levels, whereas dsDNA levels were reduced, thereby supporting that the FACT complex is required to solve R-loops and for proper levels of 5mC at the analyzed promoters, similarly as the HMGA2 lyase activity (Figs. 6d and 7a). Previously, we have shown that ATM loss-of-function (LOF) blocks TGFB1-induced and HMGA2-mediated transcription activation10. To confirm the causal involvement of ATM in the mechanism of transcription regulation proposed here (Fig. 7b), the levels of pH2A.X and H2A.X at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters were analyzed by ChIP using chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ MEF and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF that were treated with DMSO (control) or an ATM inhibitor (ATMi; KU-55933) and doxycycline as indicated (Fig. 7c). Interestingly, ATMi treatment counteracted the rescue effect on pH2A.X levels that was mediated by inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF, without significantly affecting H2A.X levels, thereby supporting that ATM is required for the post-translational modification of H2A.X rather than for the deposition of H2A.X into the analyzed promoters. In addition, we monitored 5mC levels by DIP at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters (Fig. 7d) and found that ATM-LOF also counteracted the rescue effect on 5mC levels mediated by inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF, thereby supporting that phosphorylation of H2A.X at S139 is required for proper 5mC levels. The results obtained after ATM-LOF (Fig. 7c, d) support that ATM acts downstream of HMGA2 and the FACT complex.

Gadd45a has been reported to promote transcriptional activation by repair-mediated DNA demethylation19. Thus, we investigated the potential involvement of Gadd45a in the order of events proposed here (Fig. 7b). To this purpose, we analyzed the effect of Gadd45a-specific LOF using small interfering RNA (siRNA; siG45a; Supplementary Fig. 8c) on pH2A.X, H2A.X and 5mC levels at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters in Hmga2 + /+ MEF and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 7e, f). While siG45a transfection counteracted the rescue effect on 5mC levels mediated by inducible expression of WT HMGA2 in Hmga2−/− MEF (Fig. 7f), it did not significantly affect pH2A.X and H2A.X levels (Fig. 7e), confirming that GADD45A is required for proper 5mC levels but not for pH2A.X and H2A.X levels. Further, we found that GADD45A gain-of-function (GOF) after transfection of a human GADD45A expression construct into mouse lung epithelial (MLE-12) cells reduced 5mC levels in HMGA2-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 8d, e). Our results (Fig. 7e, f and Supplementary Fig. 8d, e) indicate that GADD45A acts downstream of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis (Fig. 7b). Confirming this interpretation, ChIP-seq using GADD45A-specific antibodies and chromatin isolated from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF (Supplementary Fig. 8f) revealed that GADD45A and pH2A.X are enriched at similar regions respective to TSS of the top 15% candidates. Moreover, ChIP analysis of the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters using GADD45A- or TET1-specific antibodies and chromatin from Hmga2 + /+ and stably transfected Hmga2−/− MEF that were treated with DMSO (control) or doxycycline (Fig. 7g) showed that Hmga2-KO abrogated GADD45A and TET1 binding to the analyzed promoters. Strikingly, inducible expression of WT HMGA2 reconstituted GADD45A and TET1 binding to the analyzed promoters, whereas RΔA HMGA2 did not rescue the effect induced by Hmga2-KO.

We have shown that genetic ablation of Hmga2 increased R-loop levels (Fig. 6d) and reduced GADD45A binding (Fig. 7g) at the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters. Interestingly, Arab and colleagues recently reported that GADD45A preferentially binds DNA-RNA hybrids and R-loops rather than single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds) DNA or RNA18. To elucidate these at first glance contradictory results, we performed DRIP using the antibody S9.641 and chromatin from MLE-12 cells that were stably transfected with a scrambled (scr) or a Hmga2-specific short hairpin RNA construct (shHmga2) and non-treated (-) or treated with doxycycline to induce transient expression of WT or RΔA HMGA2 (Fig. 7h). WB analysis of the precipitated material revealed that both WT and RΔA HMGA2 bind to R-loops. Further, exogenous GADD45A also binds to R-loops, confirming the results by Arab and colleagues18. However, GADD45A binding to R-loops increased after inducible expression of WT HMGA2, but not after RΔA HMGA2, suggesting that DNA nicks in the R-loops increase the affinity of GADD45A to the R-loops. The results by WB after DRIP (Fig. 7h) correlate with the ChIP analysis of the Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 promoters (Fig. 7g) and were confirmed by DRIP and sequential ChIP (DRIP-ChIP; Supplementary Fig. 8g). Taking together, our results demonstrate that the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis acts upstream of GADD45A and facilitates its binding to R-loops at specific promoters by nicking the DNA moiety of the DNA-RNA hybrid, thereby inducing DNA repair-mediated promoter demethylation.

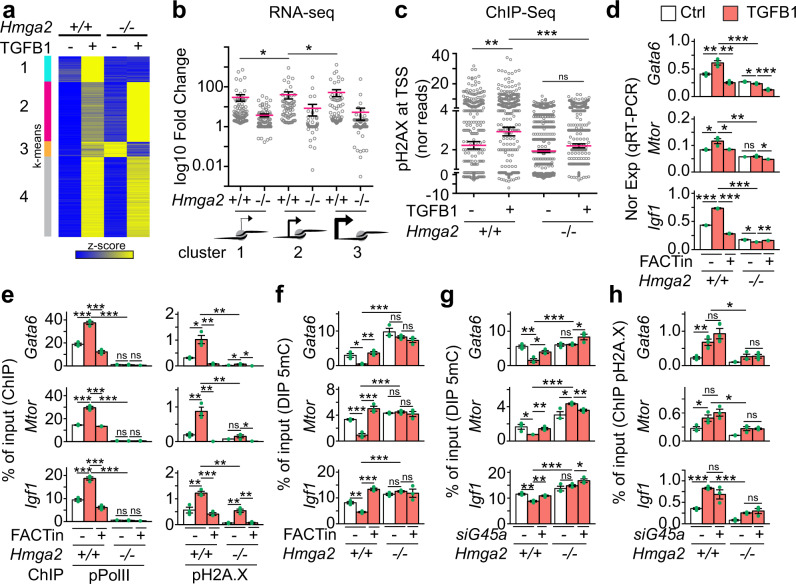

HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis mediates TGFB1 induced transcription activation

We have previously shown that HMGA2 mediates TGFB1 induced transcription10. Thus, we decided to evaluate the mechanism of transcription activation proposed here (Fig. 7b) within the context of TGFB1 signaling. We performed RNA-seq in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2 − /− MEF that were non-treated or treated with TGFB1 and visualized the results of those genes that were induced by TGFB1 treatment as heat maps after k-means clustering (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). Four clusters were identified, of which clusters 2 (n = 1471) and 4 (n = 1974) contained genes that were TGFB1 inducible in an Hmga2-independent manner. Cluster 3 (n = 381) contained TGFB1 inducible genes, whose expression increased after Hmga2-KO, while TGFB1 treatment in Hmga2−/− MEF reduced their expression. We focused on cluster 1 (n = 640) for further analysis, which contained TGFB1 inducible genes in Hmga2-dependent manner. Cross-analysis of our RNA-seq after TGFB1 treatment (Fig. 8a and Supplementary Fig. 9a) with our ChIP-seq data (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 8f) confirmed the existence of three gene groups based on the position of the first nucleosome 3′ of the TSS containing pH2A.X, which we called position clusters 1 to 3 to differentiate them from the TGFB1 inducible clusters. Consistent with our previous results (Fig. 3b), the genes in the position clusters 1 to 3 displayed increasing basal transcription activity, whereby position cluster 1 has the lowest (x̄ = 0.155), position cluster 2 the middle (x̄ = 0.662) and position cluster 3 the highest (x̄ = 2.766) basal transcription activity in Hmga2 + /+ MEF (Supplementary Fig. 9b). In addition, the position of the first nucleosome relative to the TSS also correlated with the strength of transcriptional activation induced by TGFB1 (Fig. 8b), where position cluster 1 showed the lowest (x̄ = 29.55), cluster 2 a medium (x̄ = 40.23) and cluster 3 the highest (x̄ = 51.71) transcriptional inducibility by TGFB1 in Hmga2 + /+ MEF. Remarkably, Hmga2-KO reduced the inducibility of the genes after TGFB1 treatment in all three position clusters to 3.728 (P = 2.18E-10) in position cluster 1, 8.367 (P = 1.17E-15) in position cluster 2 and 5.328 (P = 1.71E-12) in position cluster 3. ChIP-seq analysis of pH2A.X levels was also performed using the same conditions as in our RNA-seq after TGFB1 treatment (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. 9c). TGFB1 treatment increased pH2A.X levels from 2.23 to 2.937 (P = 7.5E-3) at the TSS of TGFB1 inducible cluster 1 genes in Hmga2 + /+ MEF, whereas this effect was not observed in Hmga2−/− MEF, confirming the requirement of Hmga2 for the effects induced by TGFB1.

Fig. 8. HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis mediates TGFB1 induced transcription activation.

a Heat map showing RNA-seq-based expression analysis of TGFB1-inducible genes in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF non-treated or treated with TGFB1. Data were normalized by Z score transformation and clustered using k-means algorithm. b Dot plot presenting the RNA-seq-based expression analysis of cluster 1 genes from A as log10 fold change between TGFB1-treated and non-treated MEF. Genes were grouped into the position clusters identified in Fig. 3a. Each dot represents the value of a single gene; n = 95 genes in position cluster 1; n = 64 genes in position cluster 2; n = 78 genes in position cluster 3; red line, average; error bars, s.e.m.; asterisks, P-values after one-tailed Mann–Whitney Test, *P ≤ 0.05. c Dot plot presenting ChIP-seq-based pH2A.X enrichment analysis in the top 15% candidates from Fig. 1c using chromatin from MEF treated as in a. For each gene, normalized reads in the TSS + 0.25 kb region were binned and the maximal value was plotted. Inputs were subtracted from the corresponding samples. Red line, average; n = 640 genes; error bars, s.e.m.; asterisks, P-values after one-tailed Mann–Whitney test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; ns, non-significant. d qRT-PCR-base expression analysis of HMGA2 target genes in Hmag2 + /+, Hmag2−/− MEF that were non-treated (Ctrl) or treated with TGFB1 and FACT inhibitor (FACTin; CBLC000 trifluoroacetate) as indicated. e ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and chromatin from MEF treated as in d. f DIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using antibodies specific for 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and genomic DNA from MEF treated as in d. g DIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using the indicated antibodies and genomic DNA from Hmag2 + /+ or Hmag2−/− MEF that were transfected with control (−) or Gadd45a-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) as indicated. h ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using pH2A.X-specific antibodies and chromatin from MEF treated as in g. In all bar plots, data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after two-tailed t-test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, non-significant. See also Supplementary Fig. 9. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 04.

Further, to determine the causal involvement of the FACT complex during TGFB1 induced transcriptional activation, we performed a series of experiments analyzing Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 in Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF that were non-treated or treated with FACTin (Fig. 8d–f). TGFB1 treatment in Hmga2 + /+ MEF increased the expression of Gata6, Mtor and Igf1 (Fig. 8d) as well as the levels of pPol II and pH2A.X in their promoters (Fig. 8e), whereas 5mC levels were reduced (Fig. 8f). The effects induced by TGFB1 treatment were not observed in Hmga2−/− MEF confirming the requirement of Hmga2. Further, FACTin treatment counteracted the effects induced by TGFB1 in Hmga2 + /+ MEF supporting the causal involvement of the FACT complex. Interestingly, WB analysis of protein extracts from Hmga2 + /+ and Hmga2−/− MEF (Supplementary Fig. 9d) demonstrated that the effects observed after Hmga2- and FACT-LOF take place neither affecting total SMAD2/3 levels, nor changing their activation by TGFB1. Consistent with the mechanism of transcriptional regulation proposed here (Fig. 7b) and the results in Fig. 7e, f, siRNA-mediated Gadd45a-LOF counteracted the reducing effect of TGFB1 on 5mC levels in Hmga2 + /+ MEF (Fig. 8g) without affecting the increasing effect on pH2A.X levels (Fig. 8h), thereby confirming that GADD45A acts downstream of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis.

Inhibition of the FACT complex counteracts fibrosis hallmarks in IPF

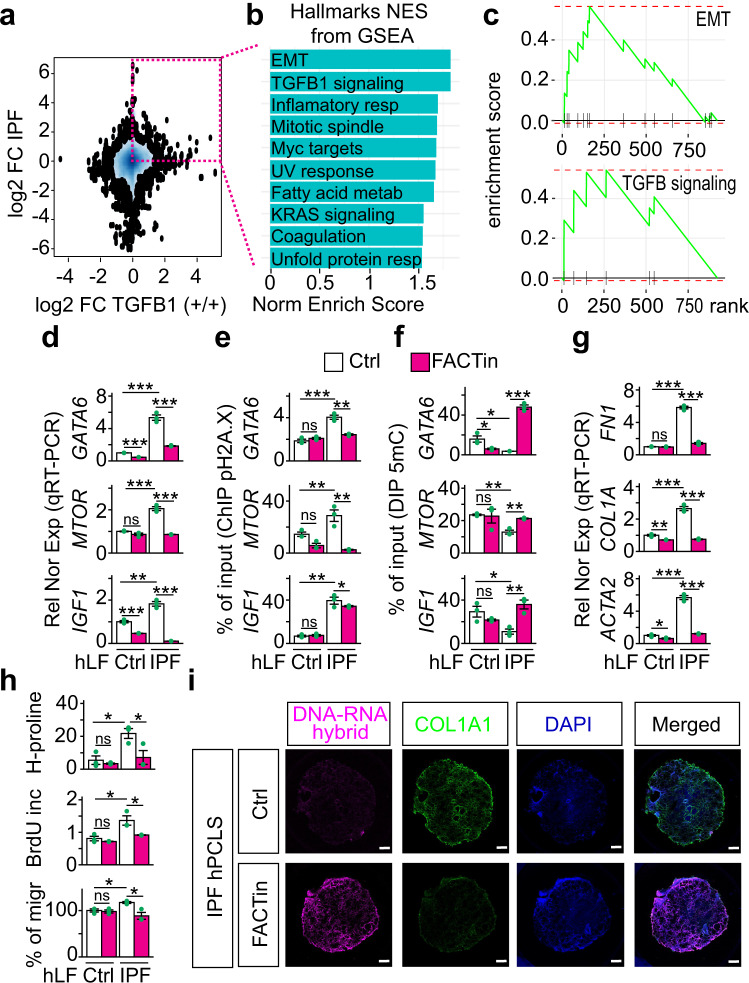

The clinical potential of the here proposed mechanism of transcription regulation (Fig. 7b) was approached by placing it into the context of the most common interstitial lung disease, IPF, in which TGFB signaling plays a key role44. RNA-seq in primary human lung fibroblasts (hLF) isolated from control (n = 3) and IPF (n = 3) patients revealed increased expression levels of HMGA2, SUPT16H and SSRP1 in IPF patients when compared to control donors (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Further, cross-analysis of RNA-seq in primary hLF isolated from control and IPF patients44 with RNA-seq in Hmga2 + /+ MEF that were non-treated or treated with TGFB (Fig. 9a) allowed us to identify 923 orthologue genes that were at least 1.5 fold significantly increased (P ≤ 0.05) in IPF hLF and in TGFB treated MEF when compared to the corresponding control cells. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)45 based on normalized enrichment scores (NSE) revealed significant enrichment of orthologue genes related to EMT (P = 6.3E-3), TGFB1 signaling pathway (P = 0.012), inflammatory response (P = 0.033), MYC target genes (P = 0.011), UV response P = 0.031), fatty acid metabolism (P = 0.029), among others (Fig. 9b). In addition, graphical representation of the enrichment profile showed high enrichment scores (ES) for EMT (ES = 0.515) and TGFB1 signaling pathway (ES = 0.706) as the top two items of the ranked list (Fig. 9c). To determine the role of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis in IPF we analyzed GATA6, MTOR and IGF1 in Ctrl and IPF hLF (Fig. 9d–f). Correlating with the results obtained in MEF after TGFB1 treatment (Fig. 8d–f), we detected in IPF hLF increased expression of GATA6, MTOR and IGF1 (Fig. 9d), as well as increased levels of pH2A.X and H2A.X in their promoters (Fig. 9e and Supplementary 10b), whereas 5mC levels were reduced (Fig. 9f). Strikingly, FACTin treatment counteracted the effects observed in IPF hLF, supporting the involvement of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis in this interstitial lung disease.

Fig. 9. Inhibition of the FACT complex counteracts fibrosis hallmarks in IPF.

a RNA-seq-based comparison of gene expression in IPF and after TGFB1 treatment. 2D Kernel Density plot representing the log2 fold change between gene expression in primary human lung fibroblasts (hLF) from IPF patients vs. control donors on the y-axis and log2 fold change between gene expression in Hmga2 + /+ MEF treated with TGFB1 vs. non-treated on the x-axis. Square, genes with log2 FC > 0.58 and P ≤ 0.05 in both, hLF IPF and TGFB1-treated MEF. P-values after Wald test. b Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the normalized enrichment scores (NES) of genes inside the square in a. EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; resp, response. c GSEA line profile of the top two enriched pathways in b. d qRT-PCR-based expression analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes in hLF from control donors (Ctrl) or IPF patients that were non-treated (Ctrl) or treated FACT inhibitor (FACTin; CBLC000 trifluoroacetate) as indicated. e ChIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using pH2A.X-specific antibodies and chromatin from hLF treated as in d. f DIP-based promoter analysis of selected HMGA2 target genes using 5mC-specific antibodies and genomic DNA from hLF treated as in d. g qRT-PCR-based expression analysis of fibrotic markers in hLF treated as in d. FN1, fibronectin; COL1A1, collagen; ACTA2, smooth muscle actin alpha 2. h Functional assays for IPF hallmarks in Ctrl or IPF hLF treated as in d. Top, hydroxyproline assay for collagen content. Middle, proliferation assay by BrdU incorporation. Bottom, Transwell invasion assay. i Representative pictures from confocal microscopy after immunostaining using the antibody S9.6 or COL1A1-specific antibody in human precision-cut lung slices (hPCLS) from IPF patients (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). The hPCLS were treated as in d. DAPI, nucleus. Scale bars, 500 μm. In all bar plots, data are shown as means ± s.e.m. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments); asterisks, P-values after tow-tailed t-test, ***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05; ns, non-significant. See also Supplementary Fig. 10. Source data are provided as a Source Data files 01 and 04.

To test this hypothesis, we monitored various hallmarks of fibrosis in Ctrl and IPF hLF, such as expression of fibrotic markers by qRT-PCR (Fig. 9g), levels of ECM proteins by Hydroxyproline and Sircol assays (Fig. 9h, top and Supplementary 10c), cell proliferation by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay (Fig. 9h, middle) and cell migration by Transwell invasion assay followed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 9h, bottom). Remarkably, FACTin treatment of IPF hLF significantly reduced all hallmarks of fibrosis analyzed, thereby suggesting the use of FACTin for therapeutic approaches against IPF. Moreover, our in vitro findings in primary hLF were also confirmed ex vivo using human precision-cut lung slices (hPCLS) from 3 different IPF patients (Fig. 9i and Supplementary Fig. 10d–g). FACTin treatment of IPF hPCLS reduced the levels of the fibrotic markers COL1A1, FN1, smooth muscle actin alpha 2 (ACTA2), the mesenchymal marker vimentin (VIM), as well as HMGA2 and pH2A.X. In contrast, the levels of DNA-RNA hybrids were increased after FACTin treatment.

Discussion

Here, we uncovered a mechanism of transcription initiation of TGFB1-responsive genes mediated by the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis. The lyase activity of HMGA2 induces DNA nicks at the TSS, which are required by the FACT complex to incorporate nucleosomes containing H2A.X at specific positions relative to the TSS. The position of the first nucleosome containing H2A.X not only correlates with the basal transcription activity of the corresponding genes, but also with the strength of their inducibility after TGFB1 treatment. Further, ATM-mediated phosphorylation of H2A.X at S139 is required for repair-mediated DNA demethylation and transcriptional activation. Our data support a sequential order of events, in which specific positioning of nucleosomes containing the classical DNA damage marker pH2A.X precedes DNA demethylation and transcription initiation, thereby supporting the hypothesis that chromatin opening involves intermediates with DNA breaks that require mechanisms of DNA repair that ensure the integrity of the genome.

Biological and clinical relevance of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis

We demonstrated the biological relevance of our data within the context of TGFB1 signaling (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9). TGFB1 treatment induced promoter specific increase of pH2A.X and pPol II, whereas 5mC levels were decreased, resulting in transcription activation in Hmga2- and FACT-dependent manner (Fig. 8a–f). Interestingly, Gadd45a-LOF interfered with the 5mC decrease (Fig. 8g), without affecting pH2A.X levels (Fig. 8h), supporting the sequential order of events proposed here (Fig. 7b), in which GADD45A acts downstream of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis. Consistent with our findings, Thillainadesan and colleagues reported TGFB induced active DNA demethylation and expression of the p15ink4b tumor suppressor gene17. While published reports showed the effect of TGFB on specific genes10,17,46, in this report we demonstrated the genome wide effect of TGFB treatment affecting the global nuclear architecture and strongly suggesting future NGS studies. Following a similar line of ideas, Negreros and colleagues recently reported genome wide changes on DNA methylation induced by TGFB147. The translational potential of our work was demonstrated within the context of IPF (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 10), in which TGFB1 signaling plays an important role. Inhibition of the HMGA2-FACT-ATM-pH2A.X axis reduced all fibrotic hallmarks in vitro (using primary hLF) and ex vivo (using hPCLS). Interestingly, the FACT complex is a potential marker of aggressive cancers with low survival rates48 and FACTin is being tested in a clinical trial for cancer treatment (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01905228, NCT02931110). Our work provides the molecular basis for future studies developing therapies against IPF using FACTin.

Methods

Key resources

Please see Supplementary Table 2 containing the key resources used in this study.

Study design

This study was performed according to the principles set out in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki; the underlying protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Medicine Faculty of the Justus Liebig University in Giessen, Germany (AZ.111/08-eurIPFreg) and the Hannover Medical School (no. 2701-2015). In this line, all patient and control materials were obtained through the UGMLC Giessen Biobank (member of the DZL Platform Biobanking) and the Biobank from the Institute for Pathology of the Hannover Medical School as part of the BREATH Research Network. We used anonymized patient material.

Cell culture

All studies were done on immortalized MEF cultivated for less than twenty passages. Hmga2 wild type (+/+) and knockout (−/−) primary mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) were isolated from mouse embryos at embryonic day E15.5 and subsequently immortalized using simian virus (SV) 4010. MEF and Human embryonic kidney cell HEK293T (ATCC, CRL-11268) were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in DMEM medium with 4.5 g/l glucose, 10% FCS 4 mM L-Glutamine, 1 mM Pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin. Mouse lung epithelial cells (MLE-12, ATCC CRL-2110) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Ham’s F-12 Nutrient Mixture (5% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Primary fibroblast from Ctrl and IPF patients were cultured in complete MCDB131 medium (8% FCS, 1% l‐glutamine, penicillin 100 U/ml, streptomycin 0.1 mg/ml, EGF 0.5 ng/ml, bFGF 2 ng/ml, and insulin 5 μg/ml)) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Because of the concern that the phenotype of the cells is altered at higher passage, cells between passages 4 and 6 were utilized in the experiments described here. All cells were washed with 1x PBS, trypsinized with 0.25% (w/v) trypsin and subcultivated at the ratio of 1:5 to 1:10.

Cell treatments, transfections and siRNA-mediated knockdown

MEF were treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline or DMSO (used as solvent for doxycycline) for 4, 6 or 24 h to induce the expression of transgenes. Initial FACT complex and ATM kinase inhibition was performed with 5 μM CBLC000 trifluoroacetate (FACTin, Sigma Aldrich) for 2 h or 1 μM KU-55933 (ATMi, Calbiochem) for 6 h, respectively. MEF were transiently transfected either with 100 nM siCtrl (negative control; AM4611, Ambion) or siGadd45a (siG45; AM16708, Ambion) for 48 h. TGFB1 signaling was induced after a 16 h starvation (cell culture medium supplemented with 1% FCS) with 10 ng/ml human recombinant TGFβ1 (Sigma Aldrich) and chromatin changes were assayed after 3 h and gene expression alterations after 24 h incubations. For IPF resolution experiments, primary hLF were treated with 5 μM FACTin for 12 h.

Bacterial culture

For cloning experiments, chemically competent E. coli TOP10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for plasmid transformation. TOP10 strains were grown in Luria broth (LB) at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm on LB agar at 37 °C overnight.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and quenched on ice with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Media was aspirated and cells were washed 3 times with ice cold PBS. Cells were lifted in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% NP40, 10% glycerol) and kept on ice for additional 5 min. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min at 4 °C followed by resuspension in nuclear resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1 % SDS). Nuclei were sonicated with Diagenode Bioruptor to an average DNA length of 300–600 bp. After centrifugation, the soluble chromatin was diluted 1:20 with DB dilution buffer (50 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5% NP40, 0.2 M NaCl) and 25 μg chromatin was incubated with 3 µg of antibodies specific for H3 (Abcam), H4 (Abcam), H2A (Abcam), H2B (Abcam), pH2A.X (Millipore), H2A.X (Millipore), HMGA2 (Abcam), pPol II (Abcam), Pol II (Abcam), SSRP1 (Biolegend), GADD45A (Santacruz), TET1 (Active Motif), SPT16 (Cell Signaling) and IgG as a control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology)(see Supplementary Table 2 for antibody details). Sepharose G beads were preblocked with 1% BSA and incubated for 2 h to precipitate chromatin. Beads were washed sequentially with low salt washing buffer (20 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 0.1% SDS, 0.15 M NaCl), high salt washing buffer (20 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 0.1 % SDS, 0.5 M NaCl), LiCl washing buffer (10 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.25 M LiCl) and twice with TE buffer (10 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0). Precipitated chromatin was reverse-crosslinked by incubating with 100 μl of 1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3 and 0.5 µl RNase A (1 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then 2.5 µl of Proteinase K (10 mg/mL) was added for 2 h at 56 °C. Lastly, NaCl was adjusted to a final concentration of 0.2 M and mix was incubated for 16 h at 65°C. Immunoprecipitated chromatin was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and subjected to qPCR or next-generation sequencing. For qPCR, the percentage of input was calculated after subtracting the IgG background, if not stated elsewhere.

ChIP sequencing and data analysis in Hmga2+/+ and Hmga2−/− MEF

Libraries were prepared according to Illumina’s instructions accompanying the Ovation Ultra Low Kit. Single-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2500 machine at the Max Planck-Genome-Centre Cologne. Raw reads were visualized by FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) to determine the quality of the sequencing. Trimming was performed using trimmomatic49 with the following parameters LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:50 CROP:63 HEADCROP:13. High quality reads were mapped by using Bowtie250 to mouse genome mm10. ChIP-seq data were represented as aggregate plot or heat maps using deeptools51 following their instructions. Bam-files were converted to Bed-files using Bedtools’ bamToBed (https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) command. Genome browser snapshots were created with Homer using makeTagDirectory (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ngs/tagDir.html) and makeUCSCfile (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ngs/ucsc.html). Reads were normalized to 30 million reads. Peak calling was performed by using model-based analysis for ChIP-seq (MACS)52 with a cut-off of p < 0.01 and the following parameters: --nonmodel, –shift size 30, and an effective genome size -g of 1.87e9. Peaks were annotated by using annotePeaks.pl for mm10 from Homer (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ngs/annotation.html). From the 200,051 peaks found for pH2A.X in Hmga2 + /+ MEF, 3,935 peaks were annotated in the promoter-TSS region and were used for further analysis.

Identification of position clusters and analysis of inducibility

The enrichment of pH2A.X at TSS plus 250 bp downstream in the top 15% candidates was clustered using the k-means algorithm implemented in deeptools’ plotHeatmap command. From the 3 position clusters identified, genes in Hmga2 + /+ MEF with a FC more than 1.5 to Hmga2−/− were selected. For expression analysis, RPKMs equal or higher than 10 were considered as outliers (Number of outliers: C1, 5 genes; C2, 2 genes; and C3, 0 genes).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) and quantified using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Germany). Synthesis of cDNA was performed using 0.5-1 µg total RNA and the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using SYBR® Green on the Step One plus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The housekeeping genes Tuba1a and HPRT1 were used to normalize gene expression53. Primer pairs used for gene expression analysis are described in Supplementary Information, Supplementary Table 1.

Native chromatin fractionation and sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation

Two 15 cm dishes with MEF were washed with 1x PBS and pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor). After incubating 20 min on ice, cells were spun down at 300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The nuclei were washed once in lysis buffer and were then resuspended in 2 volumes of Low Salt Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.2 mM MgCl2 supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) including 1% Triton-X100. After 15 min incubation on ice, cells were spun down at 300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The pellet was washed in 1 ml MNase digestion buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor) and resuspended again in 1 ml MNase digestion buffer with 1,250 Units MNase (NEB Biolabs). Chromatin-MNase mix was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. MNase reaction was stopped by adding 50 mM EDTA. Samples were sonicated for 30 sec on / 30 sec off using the Bioruptor with high amplitude. Chromatin was spun down at 18,407 ×g at 4 °C for 10 min and the supernatant was used for ultracentrifugation. Sucrose gradients (5% to 40%) were prepared in 1,800 μl low salt buffer (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 20 mM NaF, 20 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor) in polyallomer centrifuge tube (Beckman). Fragmented native chromatin was loaded on top of the 9 ml 5% to 40% sucrose gradients and centrifuged for 16 h and 30 min at 168,544 ×g in a SW50.1 ultracentrifuge rotor (Beckman Coulter). Following centrifugation, 11 fractions (1000 μl each) were collected manually from the bottom of the tubes. Later, these fractions were used for western blot, mass spectrometry and NGS.

Western blotting was performed using standard methods and antibodies specific for HMGA2 (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution), pPol II (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution), total Pol II (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution), SUPT16 (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000 dilution), SSRP1 (Biolegend; 1:1,000 dilution), pH2A.X (Millipore; 1:1,000 dilution), H2A.X (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution), H2A (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution), H2B (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution) and H3 (Abcam; 1:5,000 dilution) were used (see Supplementary Table 2 for antibody details). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson; 1:10,000 dilution) using the WesternBright ECL detection solutions (Biozym). Signals were detected and analyzed with Luminescent Image Analyzer (Las 4000, Fujifilm).

Mass spectrometry: sample preparation, methods and data analysis

Proteins were methanol/chloroform precipitated from sucrose gradient fractions and dried pellets reconstituted in 8 M urea54. Per fraction, 140 µg of protein (according to the 660 nm protein assay, Pierce), were subjected to in-solution digest using protein to enzyme ratios of 1:100 and 1:50 for Lys-C (Wako Chemicals GmbH) and trypsin (Serva), respectively55. The resulting peptide mixture was desalted and concentrated using Oligo R3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) extraction56. Peptides (5 µg according to the quantitative fluorimetric peptide assay, Pierce), were subsequently labeled using 6-plex tandem mass tags (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol but employing a reagent to peptide ratio of four. Labeling channels were used for fractions from a replicate sucrose gradient as well as an internal standard sample consisting from an analogously treated mix of all replicate gradient input samples. After validation of labeling efficiency by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS2), samples were mixed by equal protein amount and 4 µg total peptides purified as well as concentrated using STAGE tips57. The subsequent LC-MS2 analysis of 50% of that peptide material used an in-house packed 70 μm ID, 15 cm reverse phase column emitter (ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, 1.9 μm, Dr. Maisch GmbH) with a buffer system comprising solvent A (5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid). Relevant instrumentation parameters are extracted using MARMoSET and included in the supplementary material as Source Data File 0358. Peptide/protein group identification and quantitation was performed using the MaxQuant suite of algorithms (v. 1.6.5.0) against the mouse uniprot database (canonical and isoforms; downloaded on 2019/01/23; 86695 entries)59,60. For downstream analysis, intensities of fractions were divided by their corresponding inputs and samples that were divided by zero were set to 0.1.

MNase-sequencing and data analysis

For DNA purification from sucrose ultracentrifugation fractions, 200 µl of fractions were resuspended with 200 µl 1× PBS and incubated with 0.5 µl RNase A (10 mg/ml, Sigma Aldrich) for 15 min at 37 °C. Samples were resuspended with 400 µl Ultra-pure phenol:chloroform (Invitrogen) and incubated for 5 min at RT. After centrifugation for 5 min at 18,407g at 4 °C, the clear phase containing DNA was transferred into a fresh tube. 40 µl of 3 M sodium acetate pH 4.9 and 1 ml of ethanol were added to the samples and DNA was precipitated for 30 min at −80 °C. DNA-mix was spun down for 30 min at 18,407g at 4 °C and the DNA pellets were washed with 70% ice cold ethanol. After centrifugation for 15 min at 18,407g at 4 °C, the pellets were dried at RT and further resuspended in 50 µl of nuclease-free water and heated for 15 min at 37 °C. DNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis or NGS.

For sequencing, purified DNA was quantified by Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 10 ng DNA was used as input for TruSeq ChIP Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) with following modifications. Instead of gel-based size selection before final PCR step, libraries were size selected by SPRI-bead based approach after final PCR with 18 cycles. In detail, samples were first cleaned up by 1x bead:DNA ratio to eliminate residuals from PCR reaction, followed by 2-sided-bead cleanup step with initially 0.6x bead:DNA ratio to exclude larger fragments. Supernatant was transferred to new tube and incubated with additional beads in 0.2x bead:DNA ratio for eliminating smaller fragments, like adapter and primer dimers. Bound DNA samples were washed with 80% ethanol, dried and resuspended in TE buffer. Library integrity was verified with LabChip Gx Touch 24 (Perkin Elmer). Sequencing was performed on the NextSeq500 instrument (Illumina) using v2 chemistry with 2x38bp paired setup. Raw reads were visualized by FastQC to determine the quality of the sequencing. Trimming was performed using trimmomatic with the following parameters LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 HEADCROP:5, MINLEN:15. High quality reads were mapped by using with bowtie2 to mouse genome mm10. For downstream analysis, fragments between 100 and 200 bp were selected and the reads were centered. Reads were normalized by an RPKM measure and represented as log2 enrichment over the corresponding inputs. To avoid division through zero, zero counts were pseudo-counted as “1”.

Generation of HMGA2 lyase mutant, doxycycline inducible MEF and stable knockdown of Hmga2 in MLE-12 cells

The lyase deficient mutant of HMGA2 was generated by sequential site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Agilent) of the first three arginines in the third AT-Hook domain. Mutagenesis primers for Hmga2 are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All constructs were sequence verified.

Replication-deficient lentiviruses containing doxycycline inducible Ctrl (Empty), Hmga2 WT-myc-his and Hmga2 RΔA-myc-his were produced by transient transfection of pCMVR8.74 (Addgene: #22036), pMD2.G (Addgene: #12259) and transfer plasmid into HEK293T cells in a 6-well plate. Viral supernatants were collected after 48 h, spun down at 3,488 ×g for 20 min, and then used to transduce immortalized MEF in the presence of polybrene (10 μg/ml, Sigma). GOF experiments for GADD45A require a high transfection efficiency which were not obtained by standard transfection protocols in MEF. Therefore, Hmga2 was knocked down by shRNA in MLE-12 cells which allowed transient transfection of a GADD45A expression construct. For a stable KD of Hmga2 in MLE-12 cells, lentiviruses for pLKO-scrambled or pLKO-shHmga2 were produced and transduced as described before. Forty-eight h later, MEF and MLE-12 cells were selected by stepwise increase with 1.5 to 3.0 or 4.0 μg/ml puromycin respectively and the pooled populations were used for various experiments.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Western blot

MEF were washed three times in cold 1× PBS and scraped in 10 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor). Cells were incubated on ice for 20 min and then spun down at 300g for 10 min at 4 °C. Nuclear cell pellets were resuspended in 300 μl Co-IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 170 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 15 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 20 mM NaF, 20 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor) and were sonicated 5 times using the Bioruptor (30 sec on, 30 sec off). Soluble chromatin and proteins were collected after centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. Precleared nuclear protein lysates (500 μg) were incubated with 20 μl of anti-c-MYC tag antibody coupled to magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific). After two hours, beads were collected and washed 4 times with 500 μl ice-cold washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 170 mM NaCl, 15 mM EDTA, 0.4% (v/v) Triton X-100, 20 mM imidazole, 20 mM NaF, 20 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor). Proteins were eluted in 30 µl 2x SDS sample loading buffer while boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. Beads were removed and protein eluates were loaded on SDS-PAGE for western blot analysis. Western blotting was performed using standard methods and antibodies specific for SUPT16 (Cell Signaling; 1:1000 dilution), SSRP1 (Biolegend; 1:1000 dilution), H2A.X (Millipore; 1:1000 dilution) and HIS-tag (Abcam; 1:1000 dilution) were used. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson; 1:10,000 dilution) using the WesternBright ECL detection solutions (Biozym). Signals were detected and analyzed with Luminescent Image Analyzer (Las 4000, Fujifilm). Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford kit (Pierce).

Preparation of nuclear, chromatin and nucleoplasm extracts

Cells were washed with 1× PBS and pellets were resuspended in 2 volumes of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor (Calbiochem)). After 20 min incubation on ice, cells were spun down at 300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and nuclei were resuspended in whole cell lysate buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA pH 8, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 25 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 40 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor). To obtain soluble nuclear proteins, resuspended nuclei were sonicated 5 times 30 s on followed by 30 sec off using the Bioruptor (Diagenode). Insoluble proteins were removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 18,407g at 4 °C.