Abstract

Background and aims:

The first hybrid artificial pancreas (AP) systems with insulin only (mono-hormonal) have recently reached the market while next generations systems are under development including those with glucagon addition (bi-hormonal). Understanding the expectations and impressions of future potential users about AP systems is important for optimal use of this clinically effective emerging technology.

Methods and results:

An online survey about AP systems which consisted of 50 questions was addressed to people with type 1 diabetes in the province of Quebec, Canada. Surveys were completed by 123 respondents with type 1 diabetes (54% women, mean (SD) age 40.2 (14.4) y.o., diabetes duration 23.7 (14.1) years, 58% insulin pump users and 43% glucose sensor users). Of the respondents, 91% understood how AP systems work, 79% trusted them with correct insulin dosing, 73% were willing to replace their current treatment with AP and 80% expected improvement in quality of life. Anxiety about letting an algorithm control their glucose levels was expressed by 18% while the option of ignoring or modifying AP instructions was favoured by 88%. As for bi-hormonal AP systems, 83% of respondents thought they would be useful to further reduce hypoglycemic risks.

Conclusions:

Overall, respondents expressed positive views about AP systems use and high expectations for a better quality of life, glycemic control and hypoglycemia reduction. Data from this survey could be useful to health care professionals and developers of AP systems.

Keywords: Artificial pancreas, Glucagon, Closed-loop insulin control, Survey, Type 1 diabetes, Psychosocial aspects

Introduction

In their attempt to achieve optimal glycemic control, people living with type 1 diabetes face various challenges that impact their health and psychosocial well-being. Technological advances such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) have come a long way in offering new options for diabetes management and improving glucose control [1,2]. However, for technological advancements to be labelled as successful, they must be well received by people with type 1 diabetes and effectively mitigate their daily diabetes burden. More recently, closed-loop insulin delivery, also known as artificial pancreas (AP), has witnessed a rapid progress [3–5]. AP systems combine CGM, CSII, and a smart dosing algorithm [5]. Interstitial CGM readings are continuously communicated to the algorithm, dictating dynamic changes in hormonal infusion to minimize hypo- and hyperglycemia [5].

The first AP systems have been recently commercialized in several countries. These systems are mono-hormonal (insulin only) and hybrid, meaning that they still require some interventions from users to announce meals and physical activities [6]. Bi-hormonal systems, which integrate glucagon in addition to insulin, aim to further reduce the risk of hypoglycemic events and/or allow targeting lower mean blood glucose levels compared to mono-hormonal systems but are not yet commercially available [4,7–9]. The eventual aim for both systems is to completely close the loop and minimally reduce the need for user input. Nonetheless, the clinical benefits of current mono- and bi-hormonal AP systems in improving time spent with glucose levels in target ranges and in decreasing hypoglycemia risks have been demonstrated mostly in short-term clinical trials [3,10].

In addition to establishing the clinical effectiveness of AP systems, assessing users’ expectations and perceptions can support the optimal development of these systems. Some AP system trials assessed the experience and collected feedback from participants through follow-up surveys [1,11–15]. But most of the trials were conducted under controlled settings; therefore, user feedback could have been influenced by the specific design and conditions of these trials. On the other hand, studies with designs based on surveys that examine perceptions and expectations exclusively of potential adult AP users are less numerous [16,17]. Additional survey studies are important to clarify what future users expect from AP systems. More knowledge about impressions and expectations of people with type 1 diabetes could help health care professionals better prepare their patients for the adoption of AP systems. Equally, researchers and companies would benefit from such information when developing AP systems and planning more advanced features in the future. The following survey study therefore sought to answer the following research question: what are the expectations and perceptions of adults with type 1 diabetes regarding future AP systems use? Accordingly, the objective of this survey study was to explore this question from the perspectives of potential future users of AP systems.

Methodology and materials

Participants and recruitment

The Survey Monkey® platform was used to create an online survey about AP systems. Inclusion criteria included adults (18 year or older) with type 1 diabetes living in Quebec, Canada using multiple daily insulin injections (MDI) or CSII with or without CGM. People with type 1 diabetes were invited to participate in the online survey through advertisement on the Facebook pages of Diabète Québec and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) as well as through the Diabetes Clinic Database at the Montreal Clinical Research Institute, as previously described [18]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Montreal Institute of Clinical Research. All participants had to consent online through The Survey Monkey® platform before being directed to the survey to be filled.

Survey organization and content

The survey was designed and enriched through an inter-disciplinary collaboration between clinicians, bioethicists, and an engineer, who were either researchers or trainees. They were respectively specialized in clinical management and technology use in type 1 diabetes, conducting quantitative and qualitative studies among health care system users, and hybrid closed-loop system algorithms. Team members, who were independent from this project, had also provided their feedback on the clarity of the questions and suggested some final minor edits. The structure was based on the models of previously published surveys by the team [18–20]. The survey, which was written in French, began with an introductory section with an image explaining the components of a hybrid AP system and later introduced the dual-hormone artificial pancreas. A total of 50 questions were either formatted with multiple choices, Likert scales (5 answers ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree plus an additional answer of “I don’t know”) or required short open answers. The questions were organized under the following themes: participant information, diabetes management, equipment and alarms, diabetes management with the artificial pancreas, issues associated with the use of an artificial pancreas, and general questions about the dual-hormone artificial pancreas after a brief description. An English translation of the survey is provided as supplementary material to this article. Issues associated with artificial pancreas use were based on the results of a literature review conducted by Quintal et al. (2019) [21].

Outcomes, comparisons and statistical analysis

The primary aim was to report the descriptive outcomes based on participants’ answers. Outcomes were presented as numbers and percentages or means (SD). No sample size calculation was possible for this primary aim. As secondary aims, we examined possible associations between the characteristics of respondents and their expectations or opinions about AP systems. For each association test, the null hypothesis was that there was no association between the variables in question. For associations between two variables Pearson’s chi-squared test was applied, (e.g., to examine the association between current insulin therapy (CSII or MDI) and willingness to wear AP components (agree vs. not agree) as 2*2 contingency table. Binary logistic regression models were also applied to examine the impact of certain factors on participants’ impressions about AP systems use, the results of which were presented as Odds Ratio (OR (95% confidence interval); p value). The basic model used included age, sex, diabetes duration, education level, CGM use and CSII use as independent variables. Additional independent variables were in certain instances integrated into the basic model if they could explain the participants’ responses. Hosmer and Lemshow test was applied to test for models’ fitness. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS software (version 25). A p value < 5% was chosen as a statistically significant threshold.

Results

Completed surveys were submitted online by 136 participants. Three surveys were excluded from analysis because they belonged to participants who had type 2 diabetes (one) or who were younger than 18 years old (two). Ten surveys were excluded because they were filled twice by 5 participants. Thus, data was reported and analysed for 123 adequately filled surveys. Given that the survey was only distributed online, it was neither possible to track the total number of participants who saw the announcement but declined to fill the survey nor to identify their reasons for not participating.

Participants’ characteristics and challenges in diabetes management

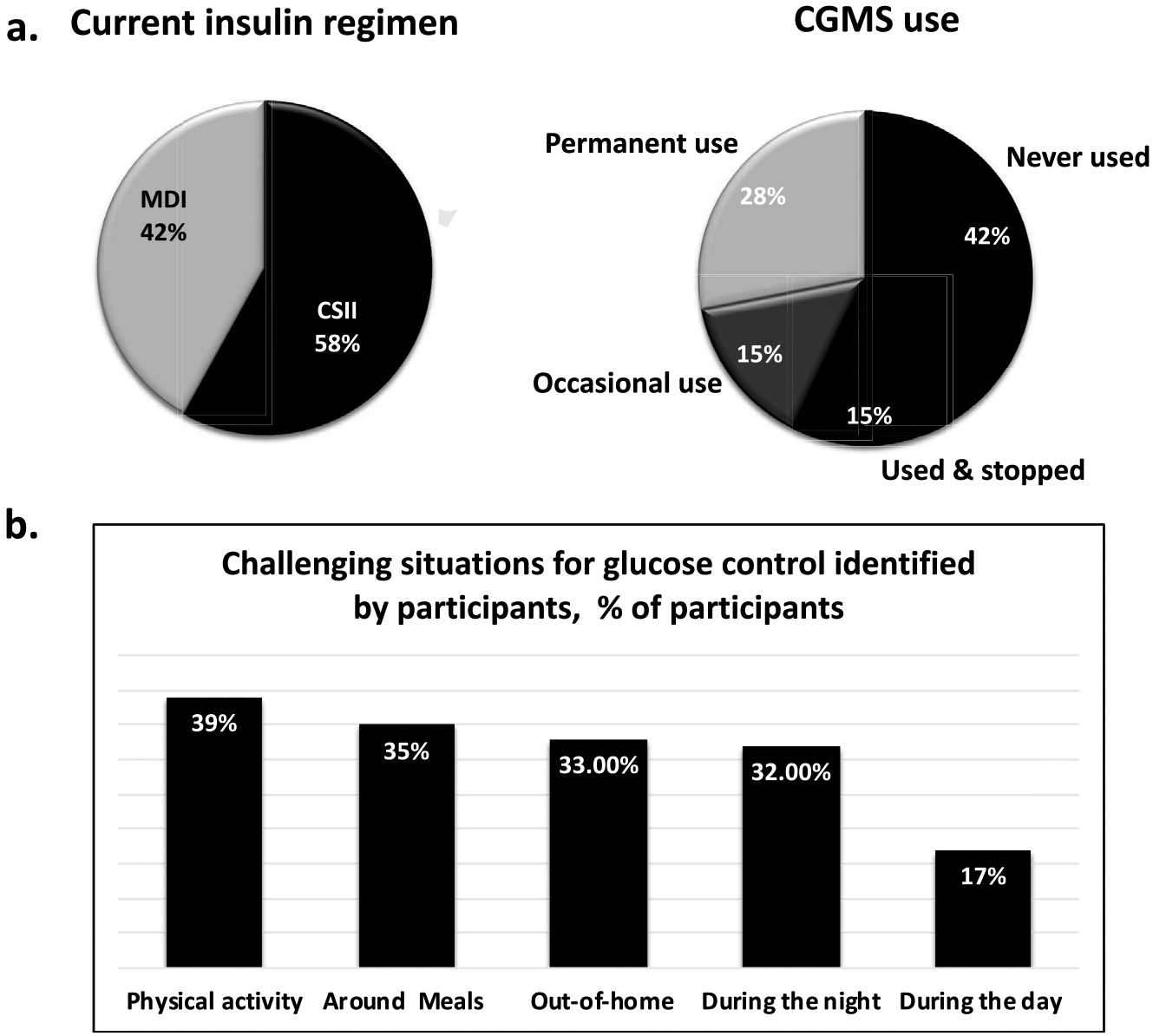

The 123 participants (54% women) had a mean (SD) age of 40.2 (14.4) years old, have had their diabetes for 23.7 (14.1) years and 81% of them had at least a collegial level of education (58% at university level, 23% collegial level, 17% high school level, 3% primary or other). The last glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was reported to be ≤ 7% (53 mmol/mol) by 37% of the participants, 7–8% (53–64 mmol/mol) by 34%, above 8% (64 mmol/mol) by 19% and was unknown by 10%. CSII and MDI were used by 58% and 42% of the participants, respectively. CGM was utilized permanently or occasionally by 43% of the participants and 37% were concomitant users of CSII and CGM (Fig. 1). The most challenging situations for glucose control are presented in Fig. 2 and anxiety levels about glucose control in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Participants’ current status of diabetes management.

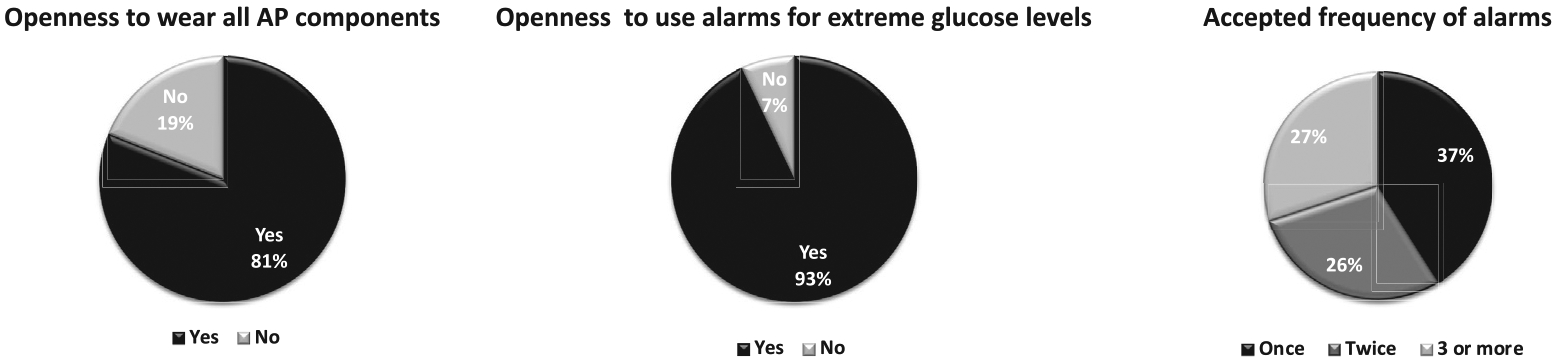

Figure 2.

Impressions about AP components use.

Table 1.

Satisfaction and anxiety with diabetes management.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with glucose control % | ||||||

| Overall control | 15 | 42 | 18 | 21 | 4 | 0 |

| Around meals | 7 | 48 | 11 | 27 | 6 | 1 |

| Around exercise | 9 | 31 | 26 | 23 | 10 | 2 |

| Nighttime | 14 | 43 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 1 |

| Anxiety about % | ||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 32 | 25 | 14 | 19 | 10 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 32 | 37 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 0 |

Expectations about AP system use

In the following sections, the combined percentages of participants who responded with “strongly agree” or “agree” are specified, while detailed distributions of other responses such as “neutral”, “disagree”, “strongly disagree” or “I don’t know” can be consulted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Management issues and psychosocial issues related to pancreas features and use.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managing diabetes with AP % | ||||||

| Understand how AP functions | 47 | 44 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Trust AP with insulin dosing | 35 | 44 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Prefer AP over current therapy | 41 | 32 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 7 |

| AP would help during physical activity | 39 | 29 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 11 |

| AP might have an effect on meal planification | 20 | 23 | 27 | 17 | 5 | 8 |

| Psychosocial aspects of AP use % | ||||||

| Better quality of life with AP than current treatment | 58 | 22 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Have the ability to ignore or adjust AP recommendations | 43 | 45 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Anxious about letting AP control your glycemia | 4 | 14 | 28 | 43 | 7 | 4 |

| Anxious about letting AP collect your own data | 2 | 2 | 11 | 42 | 42 | 0 |

| AP might have an impact of who you are | 11 | 15 | 25 | 21 | 25 | 3 |

| AP might affect your body image | 7 | 27 | 16 | 25 | 23 | 2 |

| Close relatives will react positively to AP | 53 | 32 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Particularities of bi-hormonal AP in comparison to mono-hormonal | ||||||

| Better glycemic control | 38 | 40 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Better quality of life | 32 | 35 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

Managing diabetes with AP systems

Of the total respondents, 91% understood how AP systems work, 79% trusted AP systems with correct insulin dosing, 73% were willing to replace their current treatment with an AP system, 68% declared that physical activity would be facilitated by AP systems and 43% anticipated modifications in the way they plan their meals during AP system use. After accounting for age, sex, education level, CSII use, CGM use and diabetes duration, the following associations were significant. 1) Better odds for understanding AP functioning were found for CSII users (OR (95% CI); 12.2 (1.2–119.9); p = 0.03). 2) Better odds for trusting the algorithm with correct insulin dosing were found in males (3.4 (1.1–10.1; p = 0.03). 3) Regarding willingness to replace current treatment modality with an AP system, additional variables were accounted for, notably AP function understanding, AP trusting with insulin dosing, hypoglycemia anxiety, hyperglycemia anxiety, the overall satisfaction with glucose control and the perceived effect on quality of life. Of these factors, willingness to shift to an AP system was positively associated with expecting improvement in quality of life (10.9 (3.0–39.7); p < 0.001), with trusting AP systems with insulin dosing (3.6 (1.0–12.6); p = 0.047), and was negatively associated with the overall satisfaction over their current glucose control (0.2 (0.07–0.9); p = 0.04).

Impressions about AP components use

Openness to wearing all three AP system components (Fig. 2) was more frequent in CSII vs. MDI users (87% vs. 73%; p = 0.04), and in CGM users vs. non-users (92% vs. 74%; p = 0.009). Calibrating the CGM with capillary values was not perceived as a problem by 75% of participants; more so for CGM users vs. non-users (86% vs. 67%, p = 0.03), no significant difference was perceived by those using CSII vs. MDI (77% vs. 71%; p = 0.1). When accounting simultaneously for age, sex, education level, current CSII and CGM use, none of these factors was significantly associated with the readiness to wear all AP components or to calibrate CGM. The acceptance of alarm use is presented in Fig. 2.

Psychosocial aspects related to AP system use

Of the total participants, 80% would expect an improvement in their quality of life with an AP system. To further examine the factors that could modulate quality of life expectation, the basic regression model was applied with the addition of anxiety about hypo- or hyperglycemia and satisfaction with overall glucose control as covariables. Those who were satisfied with their overall glucose control were at lower odds of expecting improved quality of life with AP systems (0.1 (0.04–0.5); p = 0.003). On the other hand, CSII users were at higher odds of expecting improved quality of life (5.4 (1.4–20.2); p = 0.01. No other factors were significantly associated with quality of life expectations with AP system use. On the other hand, 26% and 34% thought AP systems would have an impact on who they are and on their body image respectively; while 85% felt their loved ones would positively perceive their use of AP systems. Applying the basic regression model for the effect of AP use on “who the person is”, older people were at lower odds of expecting any such effect (0.9 (0.8–0.9); p = 0.004) in contrast to those with longer disease duration (1.1 (1.0–1.1); p = 0.03). Females were 3.3 times more likely to report that AP systems could impact their body image than males (3.3 (1.1–10.0); p = 0.03). None of the factors in the basic regression model were significantly associated with the expected reactions from close relatives to an AP system. Anxiety about letting an intelligent algorithm control their glucose levels was expressed by 18% of participants while 88% affirmed that it would be important for them to be able to ignore or modify AP system recommendations when they want to. Only 4% felt anxious about letting AP systems collect their personal and glycemic data (Table 2).

Perceptions of bi-hormonal AP systems

Bi-hormonal AP systems were reported to be useful by 83% of participants in further reducing hypoglycemic risk. A reduction in overall anxiety related to diabetes management was expected by 63% of the respondents and in the need for snacks by 41%. Only 6% of participants did not think it would be useful. Participants thought that bi-hormonal AP systems would be most useful in these situations, in order of importance: physical activity (39% of participants), meals (35%), when not at home (33%), during the night (32%), and during the day (17%). More specifically, in terms of physical activity-related hypoglycemia, 89% thought bi-hormonal AP systems would be very useful or useful. Better glycemic control and quality of life with bi-hormonal AP systems in comparison to mono-hormonal AP systems were expected by 78% and 67% of participants, respectively (Table 2). Participants expected the following negative aspects linked to bi-hormonal PA use, in order of importance: plausibly higher costs (58% of participants), the addition of a medication (17%), the complexity of the system with the need of two injection sites (24%), and body image (5%). Overall, 28% of participants did not expect negative issues arising from bi-hormonal AP systems. When asked about what the preferred type of treatment if all options were made available in the market while disregarding the issue of higher costs with the addition of glucagon, 71% chose bi-hormonal AP systems, 20% chose mono-hormonal AP systems, 5% chose treatment with insulin pumps, and 4% chose multiple daily insulin injections.

Discussion

The objective of this online survey was to explore the expectations and perceptions of adults with type 1 diabetes regarding future AP system use, in order to optimize the technological development and clinical integration of hybrid AP systems. Overall, participants expressed positive perceptions of AP systems and willingness to adopt them, which further validate the need for better options for diabetes management and the multiple daily challenges of type 1 diabetes management with currently available therapies.

Willingness to replace current therapy with AP was reported by 73% of the participants in our study. However, when asked to specifically choose among mono-hormonal AP systems, bi-hormonal AP systems, CSII or MDI notwithstanding considerations of availability and costs, AP systems were chosen by 91% of participants (71% for bihormonal and 20% for mono-hormonal). These percentages cohere with other published trials where AP uptake was favoured by 86% of participants in two different studies (both with small numbers of participants) and by 90% in a more recent publication [22–24]. Interestingly, predictors of readiness to shift to AP therapy included current CSII usage, dissatisfaction with current glucose control, trusting AP systems with insulin dosing and expectations for improvement in quality of life with AP system use. Indeed, the regression analysis revealed better acceptance of many AP system aspects by current users of technology to manage their disease, especially with CSII use. Our findings are in line with some existing data [16,22] but it is noteworthy that most surveys have been conducted during clinical trials of AP systems use where all patients had been CSII users before inclusion. It is therefore likely that familiarity with CSII would facilitate the acceptance of more complex technologies such as an AP system. An important finding in our study is that an overwhelming majority of participants (88%) prefer to be able to ignore or override the suggestions of the algorithm when they want. Identical wishes to override or stop AP systems were expressed by most participants in two studies that used structured and focus group interviews [25,26]. Moreover, despite almost all participants (93%) expressing openness to use alarms, the tolerated alarm frequency varied among participants with around one third (30%) accepting alarms at a frequency exceeding 3 times per day. These aspects might affect long term use of AP systems and should be considered in their technological development before future versions and eventually fully closed-loop systems enter the market.

Many participants reported difficulties with glucose control around physical activity (52%), meals (48%), out-of-home (46%), and during the night (43%). These results reflect their continuous struggle with type 1 diabetes management despite half of them using CSII and one third being concomitant users of CGM and CSII. Even if these situations are known to be challenging to people living with type 1 diabetes, existing and developing AP systems will need to be optimized in terms of their algorithms in situations like physical activity and meal-taking [9,27,28]. Until better performing systems are made available, future users will need to be educated about the need for user involvement to plan physical activity and meals [21]. Since education on the capabilities of AP systems can help foster realistic expectations among prospective users (21), it may also favour their eventual satisfaction with these systems and their overall clinical success.

Trust in AP systems’ algorithm with insulin dosing was expressed by 79% of the participants. This is coherent with the results of a clinical trial in adults with type 1 diabetes who used AP systems for 11 days, in which 70% of adults trusted the system [29]. A majority of participants (80%) expected an improvement in their quality of life with an AP system. Published surveys assessing expectations and quality of life, conducted with different designs during clinical trials of AP systems, all showed overall improvement in quality of life [1,11,14,15,29]. Our finding indicates that expectations regarding improvements in quality of life are generally high among participants. This reiterates the need to educate prospective users on the limitations of AP systems to ensure that their expectations are realistically aligned with the performance of these systems once they will enter the market (21).

Participants were not anxious about sharing their personal data and glycemic profiles through AP systems, which likely reflects the ubiquitous presence of information technology in daily life. Although not expressed by the majority as with other positive aspects, impacts of AP systems on who the person is and on body image were expected by close to one third of participants (26% and 34%, respectively). The effect on body image was significantly more reported by females (46%) than males (18%). Such concerns, if sufficiently significant, could disproportionately impact the uptake of AP systems among women when commercialized. To minimize the uneven distribution of inconveniences of AP systems on body image and personal identity, these concerns should be mitigated during the process of AP systems development in advance to their commercialization (e.g., smaller devices).

Specific questions addressed the expectations and perceptions about glucagon addition in bi-hormonal AP systems while comparing them to those for mono-hormonal systems, which has not been reported in published studies to our knowledge. Interestingly, a majority of participants expected usefulness of glucagon addition to further decrease hypoglycemic risks (83%) and to facilitate glucose control around many known challenging conditions such as physical activity and meals. Importantly, 63% of participants expected bi-hormonal AP systems to decrease anxiety related to disease management burden. After 11 days of bi-hormonal AP system use by adults with type 1 diabetes, 64% of the participants in the clinical trial reported feeling a decrease in disease burden in comparison to their usual care [29]. Participants also expected greater improvements in quality of life and glucose control with bi-hormonal AP systems (67% and 78% respectively) over mono-hormonal AP systems. This finding mirrored the larger proportion of participants willing to adopt AP systems that would be bi-hormonal (71%) rather than mono-hormonal (20%) if both were available at comparable costs. Together, these results suggest that people with type 1 diabetes are very open to try more advanced management technologies in light of expected improvements to their hypoglycemia risk and overall glucose control around challenging situations such as physical activity despite the greater complexity of these technologies.

Limitations

The study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. Half of the participants were university graduates similar to rates in previous online type 1 diabetes surveys conducted in Quebec [19,20]. Educated participants may be more prone to respond to such surveys and this might exert a selection bias on the responses, but we have adjusted for education level when possible in our analysis. The survey was offered in French so English speaking potential participants might have been missed but this should not have affected the overall validity of the responses. On the other hand, our study tried to investigate general aspects of AP systems in its mono-hormonal system but covered as well specific questions about bi-hormonal systems. Some questions involved comparisons between mono and bi-hormonal systems, which are not covered in other published trials. Another possible limitation of this survey is that it did not address potential technical problems with AP components such as difficulties with CSII catheters or CGM accuracies or stable glucagon formulations. However, these AP components are undergoing rapid technological improvements. Thus, these technical aspects were beyond the direct scope of this survey.

Conclusion

Prospective users of AP systems who participated in this online survey held positive expectations and perceptions toward AP systems, and are willing to replace their current therapies with AP systems. Their interest in using AP systems, both mono-hormonal and bi-hormonal, can be attributed to the anticipation of improvement in glucose control, decreased hypoglycemia risks and better quality of life with AP systems. The findings reported in our study better equip healthcare professionals to adequately align the expectations of prospective users with the performance and limitations of AP systems that will be commercially available. These findings are also informative to developers of AP systems by hinting to possible improvements that could be made to these modalities before they are commercialized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Writing of this paper was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH (RRL; 1 DP3 DK106930-01), a summer internship scholarship from the IRCM, graduate student awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (AQ and NT), a scholarship from Fonds de Recherche Santé Québec (NT) and a career award from the Fonds de recherche Québec-Santé (ER). We thank all the participants to this project for their time and commitment to research. We would like equally to thank Dr Ahmad Haidar for his input at the initiation of this survey.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

RRL has received research grants from the Canadian Diabetes Association, Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Cystic Fibrosis Canada, Merck, Novo-Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis. He has been a consultant or member of advisory panels of Abbott, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer, Carlina Technology, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, Neomed, Novo-Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda. He has received honoraria for conferences by Abbott, Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck, Novo-Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis. He has received in kind contributions related to closed-loop technology from Animas, Medtronic, and Roche. He also benefits from unrestricted grants for clinical and educational activities from Eli Lilly, Lifescan, Medtronic, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He holds intellectual property in the field of type 2 diabetes risk biomarkers, catheter life and the closed-loop system. RRL, LL and VM received purchase fees from Eli Lilly in relation with closed-loop technology. LL received consulting fees from Lilly and Dexcom, and received (to institution) research funding from Merck, Astra-zeneca and Sanofi. NT, AQ and ER do not have any competing interests to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.10.006.

References

- [1].Musolino G, Dovc K, Boughton CK, Tauschmann M, Allen JM, Nagl K, et al. Reduced burden of diabetes and improved quality of life: experiences from unrestricted day-and-night hybrid closed-loop use in very young children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2019;20(6):794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Diabetes A 7. Diabetes technology: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl 1):S71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bekiari E, Kitsios K, Thabit H, Tauschmann M, Athanasiadou E, Karagiannis T, et al. Artificial pancreas treatment for outpatients with type 1 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;361:k1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thabit H, Hovorka R. Coming of age: the artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2016;59(9):1795–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Taleb N, Tagougui S, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Single-hormone artificial pancreas use in diabetes: clinical efficacy and remaining challenges. Diabetes Spectr 2019;32(3):205–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, Buckingham BA, Bode BW, Tamborlane WV, et al. Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Am Med Assoc 2016;316(13):1407–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Haidar A, Legault L, Messier V, Mitre TM, Leroux C, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Comparison of dual-hormone artificial pancreas, single-hormone artificial pancreas, and conventional insulin pump therapy for glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: an open-label randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Taleb N, Emami A, Suppere C, Messier V, Legault L, Ladouceur M, et al. Efficacy of single-hormone and dual-hormone artificial pancreas during continuous and interval exercise in adult patients with type 1 diabetes: randomised controlled crossover trial. Diabetologia 2016;59(12):2561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tagougui S, Taleb N, Rabasa-Lhoret R. The benefits and limits of technological advances in glucose management around physical activity in patients type 1 diabetes. Front Endocrinol 2018;9:818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weisman A, Bai JW, Cardinez M, Kramer CK, Perkins BA. Effect of artificial pancreas systems on glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outpatient randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5(7):501–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Barnard KD, Wysocki T, Thabit H, Evans ML, Amiel S, Heller S, et al. Psychosocial aspects of closed- and open-loop insulin delivery: closing the loop in adults with Type 1 diabetes in the home setting. Diabet Med 2015;32(5):601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Iturralde E, Tanenbaum ML, Hanes SJ, Suttiratana SC, Ambrosino JM, Ly TT, et al. Expectations and attitudes of individuals with type 1 diabetes after using a hybrid closed loop system. Diabetes Educ 2017;43(2):223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tanenbaum ML, Iturralde E, Hanes SJ, Suttiratana SC, Ambrosino JM, Ly TT, et al. Trust in hybrid closed loop among people with diabetes: perspectives of experienced system users. J Health Psychol 2020;25(4):429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kropff J, DeJong J, Del Favero S, Place J, Messori M, Coestier B, et al. Psychological outcomes of evening and night closed-loop insulin delivery under free living conditions inpeople with Type 1 diabetes: a 2-month randomized crossover trial. Diabet Med 2017;34(2):262–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ziegler C, Liberman A, Nimri R, Muller I, Klemencic S, Bratina N, et al. Reduced worries of hypoglycaemia, high satisfaction, and increased perceived ease of use after experiencing four nights of MD-logic artificial pancreas at home (DREAM4). J Diabetes Res 2015;2015:590308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oukes T, Blauw H, van Bon AC, DeVries JH, von Raesfeld AM. Acceptance of the artificial pancreas: comparing the effect of technology readiness, product characteristics, and social influence between invited and self-selected respondents. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019;13(5):899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van Bon AC, Brouwer TB, von Basum G, Hoekstra JB, DeVries JH. Future acceptance of an artificial pancreas in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2011;13(7):731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Quintal A, Messier V, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Racine E. A qualitative study exploring the expectations of people living with type 1 diabetes regarding prospective use of a hybrid closed-loop system. Diabet Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fortin A, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Roy-Fleming A, Desjardins K, Brazeau AS, Ladouceur M, et al. Practices, perceptions and expectations for carbohydrate counting in patients with type 1 diabetes - results from an online survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;126:214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Taleb N, Messier V, Ott-Braschi S, Ardilouze JL, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Perceptions and experiences of adult patients with type 1 diabetes using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy: results of an online survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;144:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Quintal A, Messier V, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Racine E. A critical review and analysis of ethical issues associated with the artificial pancreas. Diabetes Metab 2019;45(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bevier WC, Fuller SM, Fuller RP, Rubin RR, Dassau E, Doyle FJ 3rd, et al. Artificial pancreas (AP) clinical trial participants’ acceptance of future AP technology. Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2014;16(9): 590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].van Bon AC, Kohinor MJ, Hoekstra JB, von Basum G, deVries JH. Patients’ perception and future acceptance of an artificial pancreas. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4(3):596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barnard KD, Pinsker JE, Oliver N, Astle A, Dassau E, Kerr D. Future artificial pancreas technology for type 1 diabetes: what do users want? Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2015;17(5):311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Naranjo D, Suttiratana SC, Iturralde E, Barnard KD, Weissberg-Benchell J, Laffel L, et al. What end users and stakeholders want from automated insulin delivery systems. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(11):1453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Garza KP, Jedraszko A, Weil LEG, Naranjo D, Barnard KD, Laffel LMB, et al. Automated insulin delivery systems: hopes and expectations of family members. Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2018;20(3):222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gingras V, Taleb N, Roy-Fleming A, Legault L, Rabasa-Lhoret R. The challenges of achieving postprandial glucose control using closed-loop systems in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metabol 2018;20(2):245–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bally L, Thabit H. Closing the loop on exercise in type 1 diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev 2018;14(3):257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Weissberg-Benchell J, Hessler D, Fisher L, Russell SJ, Polonsky WH. Impact of an automated bihormonal delivery system on psychosocial outcomes in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2017;19(12):723–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.