Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify biomarkers and construct a diagnostic prediction model for multiple sclerosis (MS). Microarray datasets in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) were downloaded. Weighted gene coexpression analysis (WGCNA) was used to search for hub modules and biomarkers related to MS. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were used to roughly define their biological functions and pathways. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression and multivariate logistic regression analysis were used to identify the diagnostic biomarkers and construct a nomogram. The calibration curve and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were used to judge the diagnostic predictive ability. In addition, cell-type identification by estimating relative subsets of RNA transcripts (CIBERSORT) algorithm was used to calculate the proportion of 22 kinds of immune cells. GSE41850 was used as the training set, and GSE17048 was used as the test set. WGCNA revealed one hub module containing 165 hub genes. Most of their biological functions and pathways are related to cell metabolism and immune cell activation. The diagnostic nomogram contained ARPC5, ROD1, UBQLN2, ZNF281, ABCA1 and FAS. The ROC curve and the calibration curve of the training set and test set confirmed that the nomogram had great prediction ability. In addition, monocytes and M0 macrophages were significantly different between MS patients and healthy people. The expression of ARPC5, ZNF281 and ABCA1 is correlated with M0 macrophages. The nomogram provides new insights and contributes to the accurate diagnosis of MS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02675-1.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Biomarker, Nomogram, Bioinformatics

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by white matter inflammatory demyelinating lesions in the central nervous system. In general, the most frequently involved parts of the disease are the periventricular white matter, optic nerve, spinal cord, brainstem and cerebellum. The main clinical features of the disease are the white matter scattered in the central nervous system, the remission and recurrence in the course of the disease, the spatial and temporal multiplicity of symptoms and signs, and the temporal multiplicity of the course of disease. At present, the incidence rate of this disease is still rising (Spirin et al. 2020). In addition to suffering from the disease itself, patients even have suicidal intention, especially in developed countries (Kouchaki et al. 2020).

The etiology and pathogenesis of MS have not yet been fully defined. In recent years, studies have proposed a multifactor etiology theory that integrates autoimmunity, viral infection, genetic predisposition, environmental factors and individual susceptibility factors (Zheng et al. 2018; Ribatti et al. 2020; Tian et al. 2020). The diagnosis of MS is also complex, and its diagnostic criteria are constantly revised. In addition to clinical symptoms, cerebrospinal fluid examination, evoked potential and magnetic resonance imaging are of great significance in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (Polman et al. 2011). Although multiple sclerosis can be diagnosed by McDonald's diagnostic criteria, the process is complicated, and it cannot be ruled out that some other autoimmune diseases of the nervous system may be misdiagnosed.

With the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, the selection of pathogenic genes has become more economical and convenient, and high-throughput sequencing has been widely used to search for candidate genes of diseases (Høglund et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2019). According to the cell-type identification by estimating relative subsets of RNA transcripts (CIBERSORT) algorithm, we can use the chip expression matrix to roughly estimate the gene expression feature set of 22 immune cell subtypes (Newman et al. 2015). At present, an increasing number of studies have found that biomarkers such as mRNA or immune cells in blood have obvious specificity in MS patients (Lavon et al. 2019; Ahmad and Frederiksen 2020; Labib et al. 2020; Sol et al. 2020). Therefore, in this study, we obtained blood high-throughput sequencing data of MS patients and healthy people through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to construct a blood biomarker prediction model of MS.

Methods

Data collection and processing

The GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) is a common repository of high-throughput experimental data. These data include experiments based on single-channel and dual-channel microarrays, detection of mRNA, genomic DNA and protein abundance, and non-array technologies such as serial analysis of gene expression(SAGE), mass spectrometry proteomics data and high-throughput sequencing data. The inclusion criteria for extracting data from the GEO database are as follows: (1) the samples are from human blood. (2) The datasets include MS patients and healthy people, and the samples of MS patients and healthy people are from before treatment. (3) The sample size in the data set is greater than 100. After defining the data set, we downloaded the standardized matrix data from the GEO database and converted probe names into gene official names. If a probe corresponds to multiple sequencing values, we take the average value.

Weight gene coexpression analysis (WGCNA)

The WGCNA package (Langfelder and Horvath 2008) was used to perform this analysis. We first selected genes with variances greater than all quartile variances to perform WGCNA. Because the results of network module analysis are easily affected by outlier samples, it is particularly important to remove outliers before constructing the network (Chow et al. 2012). In this study, the inter-array correlation (IAC) between chips is used to evaluate the distribution of microarray data. Outliers with significantly lower mean IAC values will be removed.

The coexpression network of genes conforms to no scale phenomenon; that is, it follows a power law distribution. WGCNA selected the weighted coefficients to obtain the results that most accord with the scale-free network distribution. WGCNA realizes network construction in the form of a “soft threshold (β)”. The essence of the soft threshold (β) method is to transform the correlation coefficients in the similarity matrix in the form of function transformation to obtain the adjacency function and, on this basis, to calculate the topological overlap matrix.

An important purpose of coexpression networks is to detect a set of tightly connected gene formation modules. The method used in WGCNA is to conduct clustering by dissimilarity, and the specific algorithm is the topological overlap dissimilarity measure (TOM) to calculate the degree of correlation between genes. The division of gene modules by WGCNA is based on the high topological overlap (i.e., low dissimilarity) between genes within the module. The implementation method is to construct a hierarchical clustering tree diagram of genes according to the dissimilarity matrix and divide the gene modules by a pruning algorithm.

Ultimately, we linked genes and gene modules in the network with clinical information (MS or health status) to identify genes with potential biological significance. For any genes, gene significance (GS) relative to a certain dependent variable was defined as the correlation coefficient between its expression level and the level of the dependent variable. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used for discrete dependent variables, and the Pearson correlation coefficient was used for continuous dependent variables. For a Module, the definition of Module Significance (MS) relative to a certain dependent variable is the correlation coefficient between its characteristic gene and the level of the dependent variable. For any gene in a module, the module membership (MM) of this gene in the module is defined as the correlation coefficient between this gene and the characteristic gene of this module.

Functional enrichment analysis

For the hub module and hub genes, we used Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses to roughly define their biological functions and pathways. Go analysis is a common method for large-scale functional enrichment research. Gene function can be divided into biological process (BP), molecular function (MF) and cell composition (CC). KEGG is a widely used database that stores a large amount of data about genomes, biological pathways, diseases, chemicals and drugs. Fisher’s exact test and the Benjamin–Hochberg (B–H) multiple test correction method were used to correct the occurrence of false positives. The adjusted P < 0.05 was taken as the cutoff standard.

Construction and validation of the diagnostic nomogram

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis was performed on hub genes and immune cells to prevent overfitting and screening better variables using the data from the training set. LASSO regression analysis is characterized by variable selection and complexity adjustment while fitting the generalized linear model. Variable selection here refers to not putting all variables into the model for fitting but selectively putting variables into the model to obtain better performance parameters. Complexity adjustment controls the complexity of the model through a series of parameters to avoid overfitting (Truong et al. 2015; Vasquez et al. 2016). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed before and after feature selection using the expression profiles of all hub genes from WGCNA. The expression profile of the optimal hub gene after LASSO regression analysis was then used for PCA. After the initial screening of the best variables, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed on these variables, and the results were visualized with a nomogram. In lasso regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis, P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and calibration curve were used to judge the predictive ability of the nomogram, and the data of the training set and test set were used.

Immune cell estimation

CIBERSORT is a deconvolution algorithm and it can calculate the cell composition of complex tissues based on standardized gene expression data. This method can energy the abundance of specific cell types (Newman et al. 2015). Standardized gene matrix data were uploaded to the CIBERSORT web portal (http://cibersort.stanford.edu/) for analysis using the default signature matrix at 1,000 permutations and finally obtained the proportion of 22 kinds of immune cells. Only samples with a CIBERSORT output P < 0.05 were accepted. The Wilcoxon test was used to determine the difference in immune cell content between MS and healthy people. The Spearman correlation test was used to analyze the relationship between the expression of transcription factors and the degree of immune cell infiltration.

Results

Data collection

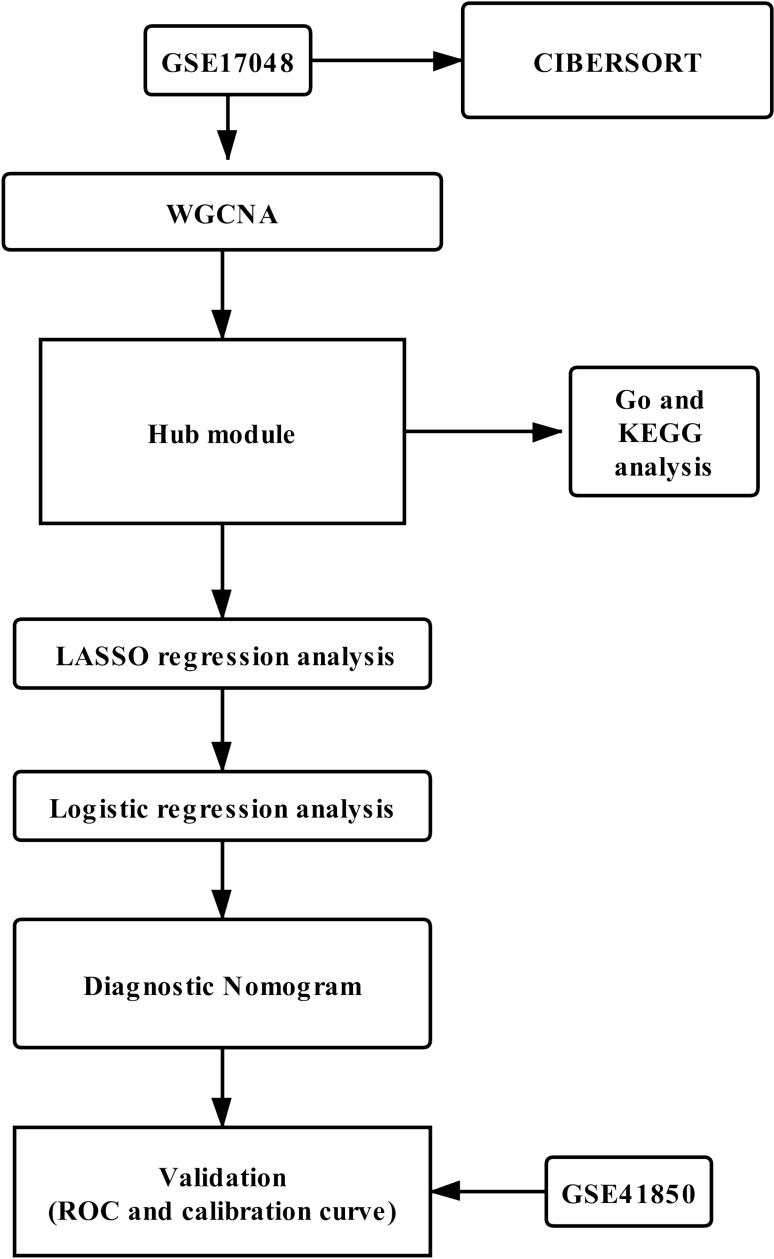

The flow of our research is shown in Fig. 1. According to our strict inclusion criteria, we included two data sets, GSE41850 (Nickles et al. 2013) and GSE17048 (Gandhi et al. 2010; Riveros et al. 2010). The basic characteristics of the two datasets are shown in Table 1. Among them, repeated samples from the same patients and MS patients with recent treatment were excluded. GSE17048 was used as the training set, and GSE17048 was used as the test set.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the analyses used in this study

Table 1.

The characteristics of microarray datasets

WGCNA

A total of 3979 genes with large variance among samples were used for WGCNA. GSM426623 was excluded an outlier (Fig. 2a), and β = 5 was the best soft threshold to perform adjacency matrix transformation (Fig. 2b). When the minimum number of genes per module was set to 50, similar modules were merged by setting MEDissThres = 0.25, and seven modules were obtained (Fig. 2c). The magenta module was identified to be positively correlated with MS and regarded as the hub module (R2 = 0.26, P = 0.003) (Fig. 2d). In addition, we identified 164 genes from the magenta module, which are shown in supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 2.

The results of WGCNA. a Clustering of samples and removal of outliers (GSM426623). b Analysis of network topology for various soft-thresholding powers. The left panel shows the scale-free fit index, signed R2 values (y-axis) and the soft threshold power (x-axis). β = 5 was chosen for the subsequent analysis. The right panel shows that the mean connectivity (y-axis) is a strictly decreasing function of the power β (x-axis). c Cluster dendrogram of genes in all patients. Each branch in the figure represents one gene, and each color represents one coexpression module. d Correlation between the gene module and clinical characteristics, including the MS and health status. e Scatter diagram for MM vs. GS in the magenta module

Functional enrichment analysis

The results of the functional enrichment analysis are shown in Fig. 3. GO analysis revealed that the magenta module was mostly enriched in the positive regulation of cellular catabolic processes, neutrophil activation, purine-containing compound metabolic processes and neutrophil activation involved in the immune response. KEGG analysis revealed that the magenta module was most enriched in Alzheimer's disease and the MAPK signaling pathway.

Fig. 3.

Enrichment analyses. a GO enrichment analysis of the magenta module. b KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the magenta module

Construction and validation of the diagnostic nomogram

Lasso analysis revealed 21 diagnostic variables: ABCA1, ANXA3, ARPC5, CYP1B1, EIF4A1, FAS, HIST1H1C, HSD17B10, HSPC159, JAZF1, OSBPL2, ROD1, RPAIN, SAMM50, SLC36A1, SPOP, SUPT16H, UBQLN2, ZFP36L1, and ZNF281 (Fig. 4a, b). The results of PCA also showed that the preliminary influencing factors obtained by lasso regression can accurately distinguish MS patients from healthy people when compared with using whole genes (Fig. 4c, d). The final diagnostic factors were as follows by multivariate logistic regression analysis: ARPC5, ROD1, UBQLN2, ZNF281, ABCA1 and FAS. The nomogram for predicting the incidence of MS is shown in Fig. 5a. The area under the curve (AUC) of the training set was 0.841 (Fig. 5b) and that of the test set was 0.761 (Fig. 5c). In addition, the calibration curve constructed by the data of the training set (Fig. 5d) and test set (Fig. 5e) also supports our nomogram with good prediction ability.

Fig. 4.

LASSO model and PCA. a, b Tenfold cross-validation for tuning parameter selection in the LASSO model. c PCA before and d after LASSO variable reduction

Fig. 5.

a Nomogram predicting MS probability. ROC curve for training set (b) and test set (c), calibration curve for training (d) and test set (e)

Immune cell estimation

The distribution of immunocyte content of all samples is shown in Fig. 6a. Among the samples, most of the immune cells in MS patients and healthy people were not significantly different. However, the contents of monocytes and M0 macrophages in MS patients were significantly higher than those in healthy people, and the difference was statistically significant (Fig. 6b). The expression levels of these six genes were not related to monocytes (Fig. 7a). However, ARPC5, ZNF281, and ABCA1 expression was correlated with M0 macrophages (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 6.

Distribution of immune cells between MS patients and healthy controls using CIBERSORT. a Barplot of each cell type in individual samples. b Violin diagram of the difference in the abundance of 22 immune cell types between sarcoidosis patients and healthy controls

Fig. 7.

The correlation between gene expression and monocytes (a) and M0 macrophages (b)

Discussion

With the continuous development of high-throughput sequencing technology, there are an increasing number of tumor (Liao et al. 2020a, b) or nontumor (Chen et al. 2020a) prediction models using transcription factors. In our study, we used data from the GEO database and high-throughput sequencing samples of MS patients and healthy people to construct a diagnostic prediction model containing transcription factors from blood. WGCNA identified the hub modules and transcription factors related to MS, and LASSO regression and multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that six transcription factors can accurately predict the incidence of MS. Through the detection of six-specific transcription factors in blood, we can judge the possibility of multiple sclerosis. Through the verification of external data, our prediction model was found to have high accuracy.

Previous studies have also focused on the construction of multiple sclerosis nomograms to determine the prognosis of patients or assist in diagnosis. For example, Manouchehrinia et al. (2019) constructed a prognostic model to predict the risk of an individual turning into secondary progressive multiple sclerosis at the onset of multiple sclerosis. Internal and external validation indicated that the nomogram was highly accurate (Manouchehrinia et al. 2019). The diagnostic nomogram constructed by radiology based on Ma et al. has clinical practical value in identifying the spectrum disorders of the neuromyelitis and the individual disease differentiation of the incidence rate of multiple sclerosis (Ma et al. 2019). However, as far as we know, there are no diagnostic predictive models related to multiple sclerosis in terms of transcriptome sequencing.

ARPC5 is a member of the actin-related protein 2/3 complex family. Its main function is to activate actin filaments and mediate actin assembly by sensing extracellular regulatory signals. It also plays an important role in the formation of pseudopodia and lamellar pseudopodia of dendritic cells (Millard et al. 2003). Choi et al. found that the differential oxidation of cysteine residues of the ARPC5 protein and the imbalance of oxidative stress may be one of the causes of severe depression (Choi et al. 2018). ARPC5 is also related to the occurrence and development of tumors. Moriya et al. (2011) found that miR-133a was significantly downregulated in lung squamous cell carcinoma cells, and transfection of miR-133a could lead to downregulation of multiple genes in lung squamous cell carcinoma cell lines, among which ARPC5 gene silencing could significantly reduce the proliferation of the lung cancer cell line P10, and ARPC5 was significantly overexpressed in 20 lung squamous cell carcinoma specimens.

ROD1 is a RNA-binding protein with four RNA recognition motifs, and it has a molecular weight of approximately 56. ROD1 inhibits the differentiation of erythrocytes and megakaryocytes in human leukemia K562 cells. In eukaryotic Schizosaccharomyces cerevisiae, NRD1 homologous to ROD1 blocks sexual contact reproduction and asexual meiosis (Yamamoto et al. 1999). There are few studies on ROD1 and multiple sclerosis, but there are many studies of ROD1 in tumors. Some studies have found that ROD1 may be a therapeutic target for gastric cancer (Zhao et al. 2008) and breast cancer (Zhou et al. 2018).

Recent studies have shown that UBQLN2 plays an important role in regulating different protein degradation pathways, including the ubiquitin proteasome system, autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum-related degradation pathways (Balendra and Isaacs 2018). Some studies have found that he is related to some nervous system diseases. For example, a mutation of the UBQLN2 gene was found in a familial case of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Picher-Martel et al. 2016), and the mutation is also associated with clinical temporal amnesia in frontotemporal degeneration (Ludolph et al. 2012). The P506S mutation of UBQLN2 may lead to the occurrence of familial multiple sclerosis, and it has an effect on both males and females and shows great phenotypic variability in the same family (Vengoechea et al. 2013).

Zinc finger protein (ZNF) refers to a class of proteins that bind to Zn2+, which can selectively bind to specific target structures and play an important role in gene expression regulation, cell differentiation and embryonic development (Eskandarian et al. 2019). ZNF281 can induce or inhibit tumor growth. It has been found that znf281 expression is usually accompanied by cell proliferation. It is a regulatory factor that can promote proliferation in fibroblasts and intestinal epithelial cells cultured in vitro (Pieraccioli et al. 2015).

The ATP-binding cassette transporter, as a key transporter of cholesterol efflux, can maintain normal brain homeostasis by scavenging toxic peptides and compounds in the brain. In addition, it can protect the brain from the harmful effects of endogenous and exogenous toxins that may enter the brain parenchyma (Jha et al. 2019). It has also been found that failure of myelin regeneration is the basis for demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis. The monosaturated fatty acids produced by stearyl COA desaturase-1 (SCD1) reduced the surface abundance of ABCA1, thus promoting lipid accumulation and inducing inflammatory phagocyte aggregation to cause demyelination (Bogie et al. 2020).

FAS is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and nerve growth factor receptor superfamily, which is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein. In recent years, some studies have shown that Fas/FasL is involved in the pathophysiological process of MS (Mohammadzadeh et al. 2012; Volpe et al. 2016; de Oliveira et al. 2017). Hagman et al. (2011) also found that the expression of sFas in the blood of MS patients was upregulated, and the FAS level in primary progressive MS was higher than that in relapsing remitting Ms. In addition, the level of sFas in patients with severe MS was higher than that in patients with stable MS, which indicates that the level of sFas may be related to the severity of Ms. FAS may promote the survival of autoimmune T lymphocytes and then cause nerve injury (Hagman et al. 2011).

Two kinds of immune cells, monocytes and M0 macrophages, found in our study can also be used as biomarkers of MS. CD40, CD86, HLA-DR and CD64 were the expression products of monocytes. In MS patients, the above expression products of intermediate (CD14++/CD16+) and nonclassical (CD14+/CD16+) monocytes were significantly increased. In addition, the secretion of IL-6 and IL-12 after LPS stimulation in vitro was higher than it was in normal subjects, suggesting that CD14++/CD16+ and CD14+ /CD16++ monocytes may participate in inflammatory reactions in MS patients (Vogel et al. 2014). A study found that the regulation of macrophage activation may affect the development of neuroinflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis. M1 macrophages are thought to be injurious to neurons, while M2 macrophages are believed to contribute to the regeneration and repair of neurons (Chen et al. 2020b).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first diagnostic prediction model for MS based on data from the GEO database. However, our research is still inadequate. First, all of our studies came from public databases, and although we performed internal validation to support the predictive power of the diagnostic model we built, we did not have our own experimental data for external validation. Second, all of our samples are from Caucasian ethnic groups, and due to the limitations of reagents and operations, the specific values in our prediction model may not be representative on a global scale. Finally, the immune cells in our prediction model appear in proportion, so the detection cost may be high in practical applications. However, this analysis still provides a new way of thinking about MS diagnosis.

Conclusions

In this study, we constructed a predictive model for the diagnosis of MS based on blood biomarkers. These results provide new insights into the accurate diagnosis of MS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

HL conceived and designed the study, acquired and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. YS and RC contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The researcher claims no conflicts of interests.

Availability of data and material

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The datasets (GSE41850 and GSE17048) provided by Gene Expression Omnibus can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

References

- Ahmad U, Frederiksen JL. Fibrinogen: a potential biomarker for predicting disease severity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102509. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balendra R, Isaacs AM. C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:544–558. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogie JFJ, Grajchen E, Wouters E, et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 impairs the reparative properties of macrophages and microglia in the brain. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20191660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chen C, Yuan X, Xu W, Yang MQ, Li Q, Shen Z, Yin L. Identification of immune cell landscape and construction of a novel diagnostic nomogram for Crohn's disease. Front Genet. 2020;11:423. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li Y, Xiao J, Zhang H, Yang C, Wei Z, Chen W, Du X, Liu J. Modulating neuro-immune-induced macrophage polarization with topiramate attenuates experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:565461. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.565461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JE, Lee JJ, Kang W, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Han PL, Lee KJ. Proteomic analysis of hippocampus in a mouse model of depression reveals neuroprotective function of ubiquitin c-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) via stress-induced cysteine oxidative modifications. Mol Cell Proteom. 2018;17:1803–1823. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA118.000835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow ML, Winn ME, Li HR, April C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Fan JB, Fu XD, Courchesne E, Schork NJ. Preprocessing and quality control strategies for illumina DASL assay-based brain gene expression studies with semi-degraded samples. Front Genet. 2012;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira GLV, Ferreira AF, Gasparotto EPL, et al. Defective expression of apoptosis-related molecules in multiple sclerosis patients is normalized early after autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;187:383–398. doi: 10.1111/cei.12895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandarian Z, Fliegauf M, Bulashevska A, Proietti M, Hague R, Smulski CR, Schubert D, Warnatz K, Grimbacher B. Corrigendum: assessing the functional relevance of variants in the IKAROS family zinc finger protein 1 (IKZF1) in a cohort of patients with primary immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi KS, McKay FC, Cox M, et al. The multiple sclerosis whole blood mRNA transcriptome and genetic associations indicate dysregulation of specific T cell pathways in pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2134–2143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman S, Raunio M, Rossi M, Dastidar P, Elovaara I. Disease-associated inflammatory biomarker profiles in blood in different subtypes of multiple sclerosis: prospective clinical and MRI follow-up study. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;234:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høglund RA, Lossius A, Johansen JN, Homan J, Benth JŠ, Robins H, Bogen B, Bremel RD, Holmøy T. In silico prediction analysis of idiotope-driven T-B cell collaboration in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1255. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha NK, Kar R, Niranjan R. ABC transporters in neurological disorders: an important gateway for botanical compounds mediated neuro-therapeutics. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19:795–811. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190412121811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchaki E, Namdari M, Khajeali N, Etesam F, Asgarian FS. Prevalence of suicidal ideation in multiple sclerosis patients: meta-analysis of international studies. Soc Work Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1080/19371918.2020.1810839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib DA, Ashmawy I, Elmazny A, Helmy H, Ismail RS. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes and neutrophils of Egyptian multiple sclerosis patients. Int J Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1812601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavon I, Heli C, Brill L, Charbit H, Vaknin-Dembinsky A. Blood levels of co-inhibitory-receptors: a biomarker of disease prognosis in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:835. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Wang Y, Cheng M, Huang C, Fan X. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis of features that control cancer stem cells reveals prognostic biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Genet. 2020;11:311. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Xiao H, Cheng M, Fan X. Bioinformatics analysis reveals biomarkers with cancer stem cell characteristics in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Front Genet. 2020;11:427. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludolph AC, Brettschneider J, Weishaupt JH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:530–535. doi: 10.1097/wco.0b013e328356d328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zhang L, Huang D, Lyu J, Fang M, Hu J, Zang Y, Zhang D, Shao H, Ma L, Tian J, Dong D, Lou X. Quantitative radiomic biomarkers for discrimination between neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and multiple sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49(4):1113–1121. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manouchehrinia A, Zhu F, Piani-Meier D, Lange M, Silva DG, Carruthers R, Glaser A, Kingwell E, Tremlett H, Hillert J. Predicting risk of secondary progression in multiple sclerosis: a nomogram. Multiple Scler. 2019;25(8):1102–1112. doi: 10.1177/1352458518783667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard TH, Behrendt B, Launay S, Fütterer K, Machesky LM. Identification and characterisation of a novel human isoform of Arp2/3 complex subunit p16-ARC/ARPC5. Cell Motil Cytoskelet. 2003;54(1):81–90. doi: 10.1002/cm.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh A, Pourfathollah AA, Sahraian MA, Behmanesh M, Daneshmandi S, Moeinfar Z, Heidari M. Evaluation of apoptosis-related genes; Fas (CD94), FasL (CD178) and TRAIL polymorphisms in Iranian multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci. 2012;312:166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y, Nohata N, Kinoshita T, Mutallip M, Okamoto T, Yoshida S, Suzuki M, Yoshino I, Seki N. Tumor suppressive microRNA-133a regulates novel molecular networks in lung squamous cell carcinoma. J Hum Genet. 2011;57:38–45. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickles D, Chen HP, Li MM, Khankhanian P, Madireddy L, Caillier SJ, Santaniello A, Cree BAC, Pelletier D, Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR, Baranzini SE. Blood RNA profiling in a large cohort of multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4194–4205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picher-Martel V, Valdmanis PN, Gould PV, Julien JP, Dupré N. From animal models to human disease: a genetic approach for personalized medicine in ALS. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:70. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0340-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieraccioli M, Nicolai S, Antonov A, Somers J, Malewicz M, Melino G, Raschellà G. ZNF281 contributes to the DNA damage response by controlling the expression of XRCC2 and XRCC4. Oncogene. 2015;35:2592–2601. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Mast cells and angiogenesis in multiple sclerosis. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:1103–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01394-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveros C, Mellor D, Gandhi KS, et al. A transcription factor map as revealed by a genome-wide gene expression analysis of whole-blood mRNA transcriptome in multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sol N, Leurs CE, Veld SGIT, Strijbis EM, Vancura A, Schweiger MW, Teunissen CE, Mateen FJ, Tannous BA, Best MG, Würdinger T, Killestein J. Blood platelet RNA enables the detection of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6:2055217320946784. doi: 10.1177/2055217320946784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin NN, Kasatkin DS, Stepanov IO, Shipova EG, Baranova NS, Vinogradova TV, Molchanova SS, Kiselev DV, Shadrichev VA, Spirina NN, Kachura DA (2020) Dinamika osnovnykh epidemiologicheskikh pokazatelei rasseyannogo skleroza po rezul'tatam sravneniya registrov patsientov 1999 i 2019 gg. v Yaroslavle [Registry-based comparison of multiple sclerosis epidemiology trend data in 1999 and 2019: the case of Yaroslavl]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 120:48–53. 10.17116/jnevro202012007248 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tian Z, Song Y, Yao Y, Guo J, Gong Z, Wang Z. Genetic etiology shared by multiple sclerosis and ischemic stroke. Front Genet. 2020;11:646. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong SN, Shin S, Byeon SD, Song J, Mo HS, Min KS. Comparative study on statistical-variation tolerance between complementary crossbar and twin crossbar of binary nano-scale memristors for pattern recognition. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2015;10:405. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-1106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez MM, Hu C, Roe DJ, Chen Z, Halonen M, Guerra S. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator type methods for the identification of serum biomarkers of overweight and obesity: simulation and application. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:154. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengoechea J, David MP, Yaghi SR, Carpenter L, Rudnicki SA. Clinical variability and female penetrance in X-linked familial FTD/ALS caused by a P506S mutation in UBQLN2. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. 2013;14:615–619. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.824001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel DYS, Heijnen PDAM, Breur M, de Vries HE, Tool ATJ, Amor S, Dijkstra CD. Macrophages migrate in an activation-dependent manner to chemokines involved in neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe E, Sambucci M, Battistini L, Borsellino G. Fas-fas ligand: checkpoint of T cell functions in multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2016;7:382. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Tsukahara K, Kanaoka Y, Jinno S, Okayama H. Isolation of a mammalian homologue of a fission yeast differentiation regulator. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3829–3841. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao AG, Li T, You SF, Zhao HL, Gu Y, Tang LD, Yang JK. Effects of Wei Chang An on expression of multiple genes in human gastric cancer grafted onto nude mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:693–700. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Chen Y, Chen H, Xiao W, Liang Y, Wang N, Jiang X, Wen S. Identification of key target genes and biological pathways in multiple sclerosis brains using microarray data obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Neurol Res. 2018;40:883–891. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2018.1497253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Tian SZ, Capurso D, et al. Multiplex chromatin interactions with single-molecule precision. Nature. 2019;566:558–562. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zou H, Wu E, Huang L, Yin R, Mei Y, Zhu X. Overexpression of ROD1 inhibits invasion of breast cancer cells by suppressing the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:2645–2653. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.