Abstract

Young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (YGBMSM) are a priority population for HIV prevention efforts. Although there has been a growing focus on dyadic HIV prevention interventions for male couples, the unique needs of partnered YGBMSM have been largely overlooked. In this qualitative study, we explored partnered YGBMSM’s perceptions of existing HIV prevention interventions to inform the design of a relationship-focused HIV prevention intervention. Between July and November 2018, we conducted in-depth interviews with 30 young partnered YGBMSM (mean age=17.8, SD=1.1). Participants described that interventions were needed to address skills regarding: (1) implicit versus explicit communication about sexual agreements; (2) boundary setting and identifying signs of abusive relationships; and (3) relationship dynamics (e.g., trust). Participants noted the absence of inclusive sexual education for them; thus, findings suggest that the provision of relationship skills training are requisites for HIV prevention interventions with YGBMSM in the US.

Keywords: HIV testing, youth, gay and bisexual men, relationships

INTRODUCTION

Young gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (YGBMSM) account for a disproportionate number of new HIV infections in the United States (US), representing 72% of new HIV infections in people between the ages of 13 and 24 and 30% of new infections among all gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) (1, 2). Central to reducing HIV incidence among YGBMSM are HIV prevention interventions that seek to encourage engagement in HIV prevention strategies (i.e. regular HIV testing and sustained pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use) and to decrease sexual risk-taking (i.e., engaging in condomless anal sex; CAS -- a primary risk factor for HIV transmission) (3). Adolescence is a period of developmental transition, as young people explore the emergence of sexual and gender identities, and begin to engage in sexual or romantic relationships (4). A central part of this process is learning to negotiate sexual experiences that might increase their risk for HIV/ sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition (5, 6). Thus, successful HIV prevention efforts for YGBMSM must recognize the roles of romantic partnerships in shaping their potential risk for HIV acquisition and provide YGBMSM with the skills to communicate with their sexual and romantic partners to promote their sexual health.

Modeling studies have identified main partners as the source of approximately one-third to two-thirds of new HIV infections among GBMSM (7, 8); this proportion may be as high as 84% among YGBMSM (7). High levels of HIV transmission within main partnerships have been attributed to a higher number of sex acts with main partners as compared to single episodes of sex with casual partners, more frequent receptive roles in anal sex with main partners, and lower condom use during anal sex with main partners (7–10). There is evidence that GBMSM in romantic relationships perceive themselves to be at lower risk of HIV infection (11, 12) and are less likely to routinely test for HIV (12, 13). However, much of this work has focused on risk behaviors among adult same-gender male couples, and there is a dearth of research that has sought to understand the sexual risk behaviors and prevention needs of partnered YGBMSM.

Successful HIV prevention for same-gender male couples should encourage the uptake of condoms and PrEP, and/or sustained ART adherence and viral suppression for couples in which one or both partners are living with HIV. A substantial body of literature demonstrates that the desire for intimacy is one of the strongest motivators for engaging in condomless sex with a primary partner (14–19), but, regardless of sexual orientation, many individuals report that condoms impede sexual intimacy (20, 21). Partnered YGBMSM may forgo condom use as a pathway to creating intimacy and trust with their partner. Studies estimate that nearly 80% of HIV-negative YGBMSM practice condomless sex within their relationships (22, 23) and some of these young men may also engage in condomless sex with other partners outside of their relationship (22, 24). Engaging in condomless sex combined with low rates of testing for HIV and other STIs, without confirming one’s own or a partner’s HIV serostatus as negative (8, 19), heightens YGBMSM’s vulnerability to HIV and other STIs (22, 23, 25, 26). Interventions designed to address these behaviors and thus decrease YGBMSM’s vulnerability to HIV necessitates that these youth are equipped with communication and behavioral skills to work with their partners effectively to reduce their risk of HIV acquisition.

Historically, public health messaging has created a strong association between condom use and partner mistrust –that is, GBMSM are admonished to use condoms every time they have sex, even with primary romantic partners, because one can never fully trust that another person is telling the truth about their sexual behaviors (27). Similarly, HIV prevention messaging has traditionally focused on risks from casual sex: the original ABCs of HIV prevention essentially recommended being faithful to one partner as a HIV prevention strategy. In this context, intimacy motives and prevention motives have been set up to directly contradict each other in a “HIV prevention paradox” (24). This is compounded with a lack of culturally-appropriate and inclusive sexual education (28) –which is often absent completely in many socially conservative U.S. states in which the prevalence of HIV is also high. The results of this lack of education is to discourage condom use among young men who are motivated to build intimacy in the relationships and may not yet have the communication skills to navigate HIV prevention (24, 29).

Over the past 10 years increasing evidence has emerged of the potential for couples-focused HIV prevention approaches to create efficacious gains in risk reduction for adult same-gender male couples (30–35). More recently there have been a few promising couples-focused HIV prevention interventions developed for YGBMSM (29, 36). One example is the 2GETHER intervention that was developed and pilot-tested with same-gender male couples ages 18 to 29 (29). The 2GETHER intervention was delivered in-person and included both group-based and couples sessions, which were designed to increase knowledge, motivation, and behavioral skills among young same-gender male dyads. However, this intervention did not include YGBMBM aged less than 18; the group most in need of an intervention to assist with the development of communication skills essential for successful negotiation with partners (29).

Couples HIV testing and counseling (CHTC) – in which both members of the dyad receive pre-test counseling, HIV testing and post-test counseling together, and prevention messages are tailored to the couples sero-status and relationship – represents one of the most effective couples-focused HIV prevention interventions. In the US, CHTC has been shown to be effective for adult same-gender male couples in promoting the formation and adherence to HIV prevention planning (37, 38) and is endorsed by the CDC as an effective HIV prevention strategy (38). Although CHTC holds promise in reducing HIV incidence among same-gender male couples in general, YGBMSM may lack the behavioral skills necessary to engage in HIV testing with their partner (29). Engaging in CHTC requires that couples discuss testing together, and young same-gender male couples may lack the skills, or confidence, for these discussions. The current study sought to explore the perspectives of YGBMSM on the acceptability of and potential barriers to engaging in CHTC, along with additional relationship-focused skills training, with the goal of informing adaptations needed to address the relationship context and unique developmental needs of young same-gender male couples.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

“We Prevent” is an ongoing study designed to develop and pilot test a relationship-focused HIV prevention intervention for YGBMSM in romantic relationships. We Prevent is funded through the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) (39, 40). The first phase of We Prevent sought to recruit 30 young YGBMSM ages 15 to 19 in romantic relationships from across the US to take part in an in-depth interview to inform intervention adaptation and development.

We recruited participants between July and November 2018, using advertisements (e.g., photos of young same-gender male couples in a range of race/ethnicities) on social media websites (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat). Recruitment photos included taglines and text that was developed with the iTech Youth Advisory Board (e.g., Help us learn about young couples and their relationships!; We want to learn about male couples and their relationships). People who clicked on the advertisement were directed to a study screener webpage that provided basic information about the study and were asked to complete a brief survey to determine eligibility. To be eligible, participants needed to be (1) between the ages of 15 and 19 years; (2) identify as being in an emotional and/or sexual relationship with another male; (3) identify as a cisgender or transgender male with the intention to have sex with men, (4) report that they have engaged in any sex (oral, anal, vaginal) in their lifetime, (5) meet the age of sexual consent in their states of residence which was developed based on gathering each state’s regulations; (6) have access to a personal device with internet access within safe and confidential location, (7) self-report being HIV negative or unknown serostatus, and (8) speak and read English. Although relationship status was an eligibility criterion, the study did not enroll both members of a dyad. Couples-based interventions requires significant coordination between partners to engage in studies, which may not generalizable to all partnered YGBMSM. Therefore, we decided not to make dyadic participation a requirement for this phase of the study in order to gather information from a diverse group of YGBMSM who may be most in need of relationship-focused HIV prevention interventions. We intentionally did not require participants to be sexually active with their current partner because we wanted to learn from YGMSM who may also be preparing to have sex in the current relationships.

Those who were eligible were then directed to a webpage that provided the consent/ assent form that explained the specific study activities. A waiver of parental consent to screen and enroll those under the age of 18 years was approved by the IRB. Once the eligible participant completed the consent/assent and provided their contact information, a study staff member emailed them a link to a brief online survey to capture participant demographics and HIV testing history. Upon survey completion, participants were scheduled for an in-depth interview conducted virtually via the VSee HIPPA compliant video-conferencing platform.

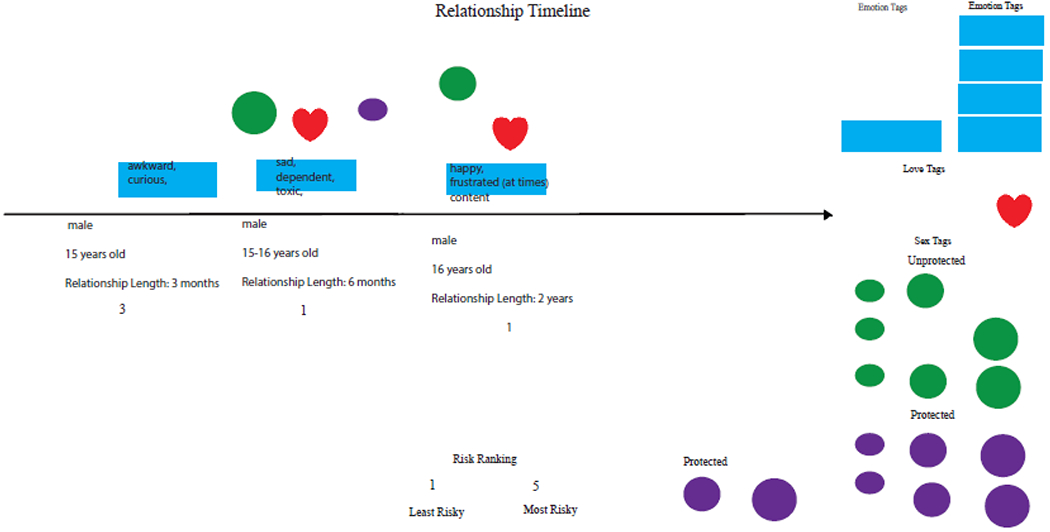

In-depth interviews adopted a participatory methods approach, in which participants created timelines that represented their relationship histories (41, 42). Using Adobe Illustrator, participants were guided through the timeline process and asked to draw a line that represented the time between their first relationship and the relationship they were in at the time of the interview. Participants guided all aspects of timeline creation and labeling. Participants were first asked to add all relationships to the timeline and then to annotate the timelines with characteristics of the relationships. For each relationship they provided a name/ nickname, duration and type of relationship (i.e. boyfriend, partner, friends with benefits). Through an action-oriented process, participants were asked a series of questions related to each relationship that resulting in them annotating their timelines with labels that were pre-determined by the study team. These labels included items mentioned above as well as, relationship rules (e.g., monogamous, open), emotions (e.g., trusting, loved, disrespected) and relationship development milestones (i.e. first sex). Interviewers asked follow-up questions as needed to fully understand the context of each relationship, probing for definitions of terms participants used to describe the relationship (i.e. boyfriend, friends with benefits). The timeline provided an anchor for discussions around relationship communication, negotiation and desires. Using the timeline, participants were asked to describe positive and negative experiences they have had regarding communication within their relationships (see Figure 1 for an illustrative example with any identifiable information redacted). Participants were also asked to provide their opinion on desired content for the proposed dyadic intervention including what skills they believed they most needed to have future successful relationships. Existing dyadic interventions – such as CHTC were described to participants to elicit suggestions for adaptation to better meet their needs. Participants received a $40 gift card for participation.

Figure 1.

Illustrative example of a relationship timeline

Data Analyses

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. We used template analysis for coding all interview transcripts (43). Codes were discussed and developed by the two lead investigators (KEG & RS) using the interview guide domains and discussed with the full research team. Three overarching themes were coded: 1) CHTC Acceptability; 2) Facilitators and Barriers to CHTC; and 3) Desired Intervention Content; each of which also had sub-themes which emerged from the research team’s analyses, discussions, and synthesis of the transcripts. The authors applied the finalized codes to all transcripts using NVivo software (version 12).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Sample

A total of 30 YGBMSM completed the study interview. Table 1 provides the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. Participants ranged in age from 15 to 19 years of age (M = 17.8, SD = 1.1). Most participants identified as gay (83.3%, n = 25), with a few identifying as bisexual (13.3%, n = 4) and one identifying as pansexual (3.3%, n = 1). All participants identified as cisgender men and resided in 30 states. Over half of the participants identified as a person of color (3.3% Black, 6.7% Asian, 3.3% Multiracial, 36.7% Latinx, and 6.7% other). Approximately one-third of the participants were completing their High School degree or GED (36.7%, n = 11) and over half of the participants had been in their current relationship for six months or less (53.3%, n = 16). Twelve participants (40%) had never been tested for HIV and nineteen (63%) had engaged in anal sex with another man in the past 3 months.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 17.8 (1.1) |

| N (%) | |

| Sexual Identity | |

| Gay | 25 (83.3) |

| Bisexual | 4 (13.3) |

| Pansexual | 1 (3.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 13 (43.3) |

| Black | 1 (3.3) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 (6.7) |

| Multiracial | 1 (3.3) |

| Latinx | 11 (36.7) |

| Other | 2 (6.7) |

| Current Education Level | |

| In High School | 9 (30.0) |

| Completing GED | 2 (6.7) |

| In Two Year College | 1 (3.3) |

| In Four Year College | 16 (53.3) |

| In Graduate School | 2 (6.6) |

| Relationship Length | |

| Less than 30 days | 5 (16.7) |

| 1 to 3 months | 5 (16.7) |

| 3 to 6 months | 7 (23.3) |

| 6 months to 1 year | 6 (20.0) |

| 1 to 3 years | 7 (23.3) |

| Lifetime HIV Testing History | |

| No | 12 (40.0) |

| Yes | 18 (60.0) |

| Anal Sex, Past 3 Months | |

| No | 11 (37%) |

| Yes | 19 (63%) |

Nine of the participants (30%) had heard of CHTC prior to the in-depth interview. Approximately three-quarters of the sample (73%, n = 22) reported in the interview that they would be willing to engage in CHTC with their current partner. Participants provided guidance for CHTC adaptation which were relevant to their unique developmental and relationship contexts and grouped into three core themes: (1) implicit versus explicit communication about sexual agreements; (2) boundary setting and identifying signs of abusive relationships; and (3) relationship dynamics, such as trust, as requisites for engaging in CHTC.

Implicit and explicit communication about sexual agreements

Most participants (83%, n = 25) reported that they were in a monogamous relationship. When asked about conversations about sexual agreements, participants often described how monogamy was an implicit understanding between themselves and their partner. The majority of participants were therefore reporting an assumption of monogamy rather than an explicitly agreed upon relationship status.

“We never really had like formal discussion about it. We just kind of like came to it, a silent agreement I guess.”

—Black gay man, age 19

“It [monogamy] was kind of assumed though because – when we like agreed to be exclusive. I think that’s just kind of the unspoken like rule that we had.”

—Pakistani bisexual man, age 19

These “silent agreements” or “unspoken rules” often occurred at the beginning of a new relationship. Participants discussed how the decision to “date” rather than just be friends meant that they were exclusive and not allowed to have sex with other partners.

“I think that was kind of just the understanding that we both had when we started dating each other that we just weren’t going to date other people. And it was never like a formal conversation we had, it was just something I think that we both knew.”

—Puerto Rican gay man, age 17

Participants also described challenges with communication. For example, several young men discussed how they did not have skills to engage in conversations that they felt dealt with difficult topics including discussing sexual agreements – or whether to have sex outside of the relationship – with their partner. Therefore, agreements were unspoken without any explicit discussions.

“Well he wouldn’t communicate what he wanted to do, you know, and I think that it’s not just him, you know, some of it was me because I think, you know, that it’s hard to communicate one way. So a lot of things were implied and neither of us really knew what to do.”

—Mexican gay man, age 18

Notably, a few participants (17%, n = 5) reported that they had had at least one conversation about sexual agreements with their partners. One young man described how he had discussed sexual agreements with one of his partners because he was “worried” about the possibility of his partner sleeping with other people.

“I didn’t really have that conversation with [name] or [name] but I did with [name]. At first, it was okay but after a while, I did feel a little worried about him seeing other people but I mean that- I just felt a little worried. But nothing ever happened so it never really caused any issues.”

—Colombian gay man, age 18

This young man went on to describe how he felt relieved that his partner said that he was not having sex with anyone else but he never expressed these feelings of relief to his partner. Even among those YGBMSM who had engaged in sexual agreement conversations, explicit discussion about sexual agreements and the meaning of sexual agreements was identified as a challenge.

Boundary setting and identifying signs of abusive relationships

Several participants noted that they wanted additional information and to be taught communication skills on boundary setting and abusive relationships. Most participants explicitly stated that boundary-setting skills, such as asking for and giving consent, were not part of their formal sex education curriculum.

“Consent is really a big issue in terms of people not realizing, you know, what counts as consent and enthusiastic consent. I don’t know a lot of people like their school system doesn’t teach on sexual health like for same sex couples almost at all.”

—Mexican pansexual man, age 16

Participants also discussed the need for further education on boundary-setting for YGBMSM, mentioning the importance of being able to say no even to their romantic partners.

“I feel like it’s important to know like you don’t really have to do anything, like there is a lot of time a lot people in relationships feel like “oh I really should do this but, I don’t want to, ” and like they do it any way. Like if you don’t want to have sex and they get upset or get angry, that’s like they need to understand that you don’t want to. So I think it’s important that if you don’t need to do anything like you make your own choices like you’re your own person. ”

—White gay man, age 17

Similarly, participants described the need for education on healthy versus unhealthy relationships, specifically as they were navigating their independence during this developmental period.

“I just think knowing the difference between a healthy and unhealthy relationship in terms of like pragmatic behavior. And like what’s considered okay and like what’s considered to be like healthy and like what’s considered to be like an overdependence on someone ”

—Pakistani gay man, age 19.

In the context of discussing HIV and STIs, participants expressed the importance of learning how to identify signs that they (or others) were in abusive relationships.

“It’s hard for people to bring up HIV and STIs so just steps on how to bring it up. Just like the classical physical abuse and then emotional abuse just things like that [signs of abuse in relationships]. ”

—Multiracial gay man, age 19

Several participants noted that CHTC could be a platform to provide young men with communication skills and boundary setting.

“I’m not sure exactly what I’d want the details to look like, but probably how to communicate with each other and be honest. And um…as far as sex…um…how to consent, and how to um…understand or ask for a consent. I think that’s a big thing. ”

—White gay man, age 17

Relationship dynamics as requisites for engaging in CHTC

Participants raised several concerns about testing for HIV in general, such as concerns about insurance and needing to go to a clinic. Most commonly, participants described how particular relationship dynamics, such as trust and commitment, would be needed for them to feel comfortable engaging in CHTC.

“You know, I think that is definitely something, you know, you have to make sure you are long term. Because if you’re like in a relationship like [with partner name] and over two months, you know, not that long that we’ve been together, you know still learning about that person and as a person you like ”

—Asian gay man, age 18

Although participants liked the idea of CHTC, they also expressed concerns about testing with their partner. For example, one participant described that there could the potential for conflict if one partner did not want to engage in the program.

“I think the biggest challenge would be if it was one person wanted to test and then the other person didn’t end up wanting to. ”

—White gay man, age 19

Additionally, one participant described how serodiscordant test results could result in a challenging situation that would be difficult to navigate.

And for the testing together part, I think it would be -- depending on the state of the relationship, it would definitely be a make or break situation as, say one person, you know, tested negative, one person tests positive, that you know for whatever that could raise so many questions for any reason.

—Hispanic gay man, age 19

Recommendations for the adaptation of CHTC for young gay and bisexual men

Although overall participants endorsed high levels of acceptability for CHTC, several participants described how they would prefer to test on their own and share their results with their partner.

“I feel like doing it themselves and then telling that person the result would be better than having them like find out together. And that’s just like really nerve-racking I feel like. So I like the idea but there is also like that it’s kind of personal like even though you’re in a relationship it’s still like it’s nerve-racking, it’s very nerve-racking.”

—Middle Eastern gay man, age 19

As noted above, participants also highlighted the critical need to ensure the counseling provided within CHTC included education on communication skills and boundary setting. Participants also noted several ways to overcome barriers and increase the likelihood that YGBMSM would engage in CHTC. That is, participants described the value of a peer counselor who could help provide counseling and tailored HIV prevention recommendations that would ease discussions about HIV testing and prevention options. A common suggestion was to make CHTC available via an online platform, which would enhance privacy and alleviate structural barriers such as the need for transportation to a clinic. Participants described how the provision of an online relationship skills program with HIV self-testing might increase acceptance. Notably, participants expressed how HIV tests might need to be sent to a friend or another close person’s home to avoid inadvertent disclosure to families.

DISCUSSION

Our study explored the perspectives of partnered YGBMSM regarding the acceptability of CHTC, potential barriers to engaging in CHTC, and necessary adaptations to account for their developmental and relationship context. Acceptability of the original CHTC program was universally high and similar to the high levels of acceptability found in other studies with heterosexual couples (44, 45), adult GBMSM (46–49), and cisgender men in partnerships with transgender women (50). Participants described the utility of working with a counselor to discuss their relationship and receive tailored counseling and prevention recommendations – reporting that having a third party lead them through prevention conversations would help ease the stress and embarrassment of talking with a partner. However, participants described that adapting CHTC or other relationship-focused HIV prevention interventions would require attending to their unique developmental and relationship contexts. Specifically, participants reported the need to provide young men with communication and relationship skills education in the absence of other educational venues (e.g., school, home). While young men wanted to talk about HIV prevention issues with their partners, they felt that lacked the ability or comfort to do so. Findings also suggested that some YGBMSM may not have the behavioral skills or established trust to engage their partner in a dyadic HIV prevention intervention – those in the early stages of their relationships felt that they had not yet reached the stage at which they could talk to their partner around issues of sex or HIV prevention. Study findings have implications for adapting CHTC and other HIV prevention interventions for YGBMSM.

Most participants reported that they were in monogamous relationships; however, when asked about conversations about sexual agreements, participants often described how monogamy was an implicit understanding, assumption or “unspoken rule” between themselves and their partner. Often these assumptions occurred at the beginning of establishing a romantic relationship – the decision to be boyfriends rather than friends or friends with benefits. Changing relationship labels or status was seen as an implicit change in expectations around sexual behavior outside of the relationship. This lack of explicit discussion and agreement on the terms of sexual behavior outside of the relationship poses a significant risk for HIV transmission for young partnered GBMSM. Although some of the participants had engaged in conversations about monogamy, results show the importance of the providing communication skills training that can equip YGBMSM with the abilities and confidence required for discussing sexual agreements and their meaning with their partners (29). Further, there is growing awareness and societal acceptance of different sexual agreements types and strategies to ensure the sexual safety of partners and their relationship (25).

Many participants described the importance of information and skills around boundary setting, sexual consent, and identifying the signs of physical and sexual abuse as desired components of HIV prevention for same-gender male couples. Evidence suggests high rates of intimate partner violence among adult GBMSM with estimates ranging from 32-78% (51–53). Studies consistently report that intimate partner violence is related to HIV transmission risk (53, 54), including in studies with YGBMSM (55). There has been a long history of research and program efforts on understanding and preventing sexual violence experienced by young cisgender women (56, 57); however, there is less focused attention to the experiences and needs of YGBMSM. Participants in this study reported that formal sexual education curriculums and violence prevention programs did not address the needs of YGBMSM. While CHTC may not be the most appropriate venue for addressing concerns around violence, it, along with other relationship-skills building approaches, could be used as a forum for discussions of sexual boundaries and consent and there is clearly a need for violence prevention programs that address the needs of young partnered GBMSM.

Similar to the results observed in previous studies (50), several participants noted that their use of CHTC would depend on their level of trust and commitment with their partner. Notably, there were concerns that a dyadic intervention could easily escalate to conflict between partners. For example, tension could arise if only one partner wanted to participate in the program or if there was a serodiscordant test result. Participants described how these types of conversations would be challenging to navigate within their current relationships. Although prior studies have found that partner support is a facilitator of CHTC acceptability (48), some of the participants expressed their desire to test on their own and receive communication skills training on how to discuss their testing results as a way to engage their partners in HIV prevention programs. In this format, YGBMSM would use the communication skills learned in an individually-based communication skills-focused session to further engage their partner in conversations about HIV prevention. As such, relationship-focused HIV prevention programs may require providing multiple options to YGBMSM based on their comfort and readiness to engage in HIV prevention conversations with their partners (e.g., participating individually or with their partners).

Participants offered several recommendations to maximize the acceptability and feasibility of CHTC and relationship-skills for YGBMSM and their partners. Participants described the utility of online platforms and HIV self-testing to enhance privacy. Providing young men with choices to engage in the program on their own and learn about communication and have the opportunity to obtain and practice such skills may be an important first step before engaging in CHTC or other dyadic interventions for those who do not yet have the skills or confidence to have these conversations with their partners.

Strengths and Limitations

The study has notable strengths. Specifically, we employed a participatory-empowered qualitative interview process to guide intervention adaptation; we used relationship timelines so that participants could openly share their reflections on their relationships and HIV prevention needs (41, 42). We enrolled YGBMSM of different ages, race/ethnicities, geographical locales, and relationship lengths to learn diverse perspective on intervention needs. Additionally, participants were highly interested and engaged with the research project as evidenced by the short amount of time that we were able to recruit a diverse sample of YGBMSM in the first phase of the We Prevent study.

However, study findings must be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Participants were recruited online using convenience sampling methods such that we may not have been able to reach YGBMSM who experience extreme structural vulnerabilities (e.g., homelessness, incarceration) or rightfully distrust researchers due to systematic racism. Participants were asked to retrospectively recall their details about their relationships; therefore, recall bias may be possible in recounting events. We only collected data only from one partner, which limits our ability to draw inferences about the specific dynamics between couples and how these dynamics influence CHTC or relationship-focused intervention acceptability. Additionally, we did not find differences by partner age in relationship dynamics, communication, and opinions about CHTC, which may be because the ages of participants’ partners ranged from 13 to 19. Thus, future research is warranted with YGBMSM who may have partners’ significantly older to understand how age discordant partnerships influences barriers and facilitators to engaging in couples-based HIV prevention interventions. The use of in-depth interviews may also have led to social desirability bias whereby participants may have under-and/or over-reported their relationship and HIV prevention intervention needs. The in-depth interviewer was a white cisgender woman, which may have also introduced social desirability or self-presentation bias.

Conclusions

YGBMSM continue to be a priority population for HIV prevention efforts; however, a limited number of interventions currently address the relationship skill needs of this group, which may be drivers of engagement in HIV prevention strategies (29, 36). This formative study provides critical insights for the future design and development of relationship-focused HIV prevention interventions for partnered YGBMSM. CHTC holds promise for YGBMSM and their partners; however, findings demonstrate the need to provide specific communication and relationship skills as an adjunct to the current program. Currently the 2GETHER couples-based intervention addresses communication and testing for young YGBMSM and their partners ages 18 to 29 using online modalities (58). Our study findings suggest that intervention efforts may also need to provide younger YGBMSM with options to participate alone or with their partner based on their comfort and confidence in communicating with their partner. Future research will also benefit from utilizing online modalities such as the current 2GETHER couples-based intervention (58) to overcome barriers to engaging in HIV prevention services (e.g., privacy, transportation). Interventions that address the desires and concerns expressed by YGBMSM could exert significant positive impact on a population that is highly vulnerable to HIV infection.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the young men who participated in this study; and staff members: Matthew Rosso, Catherine Washington, Kristina Felder-Claude, and Ramona Rai for their contributions to this study. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Sonia Lee for her support of this project. This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (U19HD89881).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of Interest: Each of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.HIV and Young Men Who Have Sex with Men [Internet]. 2014. [cited May 28, 2020]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/pdf/hiv_factsheet_ymsm.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gay and bisexual men’s health-HIV/AIDS 2015. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/msmhealth/HIV.htm.

- 3.Kann L Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12—United States and Selected Sites, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell ST, Clarke TJ, Clary J. Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. J Youth Adoles. 2009;38(7):884–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, Pingel E, Parsons JT. Spectrums of love: Examining the relationship between romantic motivations and sexual risk among young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1549–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K. Negotiating developmental transitions during adolescence and young adulthood: Health risks and opportunities. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions during Adolescence: Cambridge University Press; 1999. p. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, Lama JR, Sanchez J, Grinsztejn B, et al. What drives the US and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLoS One. 2012;7(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady S, Iantaffi A, Galos D, Rosser BRS. Open, closed, or in between: Relationship configuration and condom use among men who use the internet to seek sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1499–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax SC, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS. 2009;23(2):243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg T, Finneran C, Andes KL, Stephenson R. ‘Sometimes people let love conquer them’: how love, intimacy, and trust in relationships between men who have sex with men influence perceptions of sexual risk and sexual decision-making. Cult Health Sex. 2015;17(5):607–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson R, White D, Mitchell JW. Sexual agreements and perception of HIV prevalence among an online sample of partnered men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(7):1813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. Patterns of HIV and STI testing among MSM couples in the US. Sex Trans Dis. 2012;39(11):871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malebranche DJ, Fields EL, Bryant LO, Harper SR. Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men and Masculinities. 2009; 12( 1):90–112. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. The effects of sexual partnership and relationship characteristics on three sexual risk variables in young men who have sex with men. Arc Sex Behav. 2014;43(l):61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starks TJ, Payton G, Golub SA, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Contextualizing condom use: intimacy interference, stigma, and unprotected sex. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(6):711–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes T, Cusick L. Love and intimacy in relationship risk management: HIV positive people and their sexual partners. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2000;22(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost DM, Stirratt MJ, Ouellette SC. Understanding why gay men seek HIV-seroconcordant partners: intimacy and risk reduction motivations. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(5):513–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoff CC, Campbell CK, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA. Relationship-based predictors of sexual risk for HIV among MSM couples: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(12):2873–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adam BD, Sears A, Schellenberg E. Accounting for unsafe sex: Interviews with men who have sex with men. J Sex Res. 2000;37:24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jadack RA, Fresia A, Rompalo AM, Zenilman J. Reasons for not using condoms of clients at urban sexually transmitted diseases clinics. Sex Trans Dis. 1997;24(7):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Darbes LA, Dadasovich R, Neilands TB. Serostatus differences and agreements about sex with outside partners among gay male couples. AIDS Educat Prev. 2009;21(1):25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with HIV risk among a sample of gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Closeness discrepancies and intimacy interference: Motivations for HIV prevention behavior in primary romantic relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2019;45(2):270–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons JT, Starks TJ, Gamarel KE, Grov C. Non-monogamy and sexual relationship quality among same-sex male couples. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(5):669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez AM, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Neilands TB, Mandic CG, Darbes LA, et al. Relationship dynamics as predictors of broken agreements about outside sexual partners: implications for HIV prevention among gay couples. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1584–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myrick R AIDS, communication, and empowerment: Gay male identity and the politics of public health messages. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustanski B, Greene GJ, Ryan D, Whitton SW. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of an online sexual health promotion program for LGBT youth: the Queer Sex Ed intervention. J Sex Res. 2015;52(2):220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newcomb ME, Macapagal KR, Feinstein BA, Bettin E, Swann G, Whitton SW. Integrating HIV prevention and relationship education for young same-sex male couples: A pilot trial of the 2GETHER intervention. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2464–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu E, El-Bassel N, McVinney LD, et al. Feasibility and promise of a couples-based HIV/STI prevention intervention for methamphetamine-using, Black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez O, Wu E, Levine EC, et al. Intergration of social, cultural, and biomedical strategies into an existing couples-based HIV/STI prevention intervention: Voices of Latino male couples. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez O, Wu E, Frasca T, et al. Adaptation of a couples-based HIV/STI prevention for Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. Am J Men Health. 2015;11(2):181–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crepaz N, Tungol-Ashmon MV, Vosburgh HW, Baack BN, Mullins MM. Are couple-based interventions more effective than interventions delivered to individuals in promoting HIV protective behaviors? A meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2015;27(11):1361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaCroix JM, Pellowski JA, Lennon CA, Johnson BT. Behavioural interventions to reduce sexual risk for HIV in heterosexual couples: a meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(8):620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starks TJ, Ewing SWF, Lovejoy T, Gurung S, Cain D, Fan CA, et al. Adolescent Male Couples-Based HIV Testing Intervention (We Test): Protocol for a Type 1, Hybrid Implementation-Effectiveness Trial. JMIR Res Prot. 2019;8(6):e11186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson R, Freeland R, Sullivan SP, Riley E, Johnson BA, Mitchell JW, et al. Home-based HIV testing and counseling for male couples (Project Nexus): a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Prot. 2017;6(5):e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazzi AR, Fergus KB, Stephenson R, Finneran CA, Coffey-Esquivel J, Hidalgo MA, et al. A dyadic behavioral intervention to optimize same sex male couples’ engagement across the HIV care continuum: Development of and protocol for an innovative couples-based approach (partner steps). JMIR Res Prot. 2016;5(3):e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gamarel KE, Darbes LA, Hightow-Weidman L, Sullivan P, Stephenson R. The development and testing of a relationship skills intervention to improve HIV prevention uptake among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and their primary partners (we prevent): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Prot. 2019;8(1):e10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig K, Rosenberg E, Sanchez T, LeGrand S, Gravens L, et al. University of North Carolina/Emory Center for Innovative Technology (iTech) for addressing the HIV epidemic among adolescents and young adults in the United States: protocol and rationale for center development. JMIR Res Prot. 2018;7(8):e10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldenberg T, Finneran C, Andes KL, Stephenson R. Using participant-empowered visual relationship timelines in a qualitative study of sexual behaviour. Global Public Health. 2016;11(5–6):699–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gamarel KE, Stephenson R, Hightow-Weidman L. Technology-driven methodologies to collective qualitative data among youth to inform HIV prevention and care interventions. mHealth. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desgrees-du-Lou A, Orne-Gliemann J. Couple-centred testing and counselling for HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa. Repro Health Matters. 2008;16(32):151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darbes LA, McGrath NB, Hosegood V, Johnson MO, Fritz K, Ngubane T, et al. Results of a couples-based randomized controlled trial aimed to increase testing for HIV. J Acq Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(4):404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rendina HJ, Breslow AS, Grov C, Ventuneac A, Starks TJ, Parsons JT. Interest in couples-based voluntary HIV counseling and testing in a national US sample of gay and bisexual men: The role of demographic and HIV risk factors. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephenson R, Finneran C, Goldenberg T, Coury-Doniger P, Senn TE, Urban M, et al. Willingness to use couples HIV testing and discussion of sexual agreements among heterosexuals. Springerplus. 2015;4(1):169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neme S, Goldenberg T, Stekler JD, Sullivan PS, Stephenson R. Attitudes towards couples HIV testing and counseling among Latino men who have sex with men in the Seattle area. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell JW. Gay male couples’ attitudes toward using couples-based voluntary HIV counseling and testing. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):161–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reisner SL, Menino D, Leung K, Gamarel KE. “Unspoken Agreements”: Perceived Acceptability of Couples HIV Testing and Counseling (CHTC) Among Cisgender Men with Transgender Women Partners. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(2):366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stephenson R, Finneran C. The IPV-GBM Scale: A new scale to measure intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e62592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pantalone DW, Schneider KL, Valentine SE, Simoni JM. Investigating partner abuse among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):1031–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houston E, McKirnan DJ. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: risk correlates and health outcomes. J Urban Health. 2007;84(5):681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, et al. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;11:e1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stults CB, Javdani S, Greenbaum C, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Intimate partner violence among young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(2):215–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tetan AL, Ball B, Valle LA, Noonan R, Rosenbluf B. Considerations for the defintion, measurement, consequences, and prevention of dating violence victimization among adolescent girls. J Women’s Health. 2009; 18(7923–927). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarnquist C, Omondi B, Sinclair J, et al. Rape prevention through empowerment of adolescent girls. Pediatr. 2014;13(5):e1226–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newcomb ME, Sarno EL, Bettin E, et al. Relationship Education and HIV Prevention for Young Male Couples Administered Online via Videoconference: Protocol for a National Randomized Controlled Trial of 2GETHER. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(1):e15883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]