Abstract

Resilience may help people living with HIV (PLWH) overcome adversities to disease management. This study identifies multilevel resilience resources among African American/Black (AA/B) PLWH and examines whether resilience resources differ by demographics and neighborhood risk environments. We recruited participants and conducted concept mapping at two clinics in the southeastern United States. Concept Mapping incorporates qualitative and quantitative methods to represent participant-generated concepts via two-dimensional maps. Eligible participants had to attend ≥75% of their scheduled clinic appointments and did not have ≥2 consecutive detectable HIV-1 viral load measurements in the past two years. Of the 85 AA/B PLWH who were invited, forty-eight participated. Twelve resilience resource clusters emerged - five individual, two interpersonal, two organizational/policy and three neighborhood level clusters. There were strong correlations in cluster ratings for demographic and neighborhood risk environment comparison groups (r ≥ 0.89). These findings could inform development of theories, measures and interventions for AA/B PLWH.

Keywords: resilience, neighborhood, multilevel, health equity, mixed methods and HIV

Introduction

In the United States (US), there are substantial racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV-related outcomes. A significant proportion of people living with HIV (PLWH) are African American/Black (AA/B). Although the overall number of new HIV cases declined for this subgroup between 2010 and 2015 (1), a disproportionate percentage of PLWH are AA/B and the rate of HIV diagnosis among AA/B people remains substantially higher than that of other racial/ethnic groups (2). Further, the rates of AIDS diagnosis and death are disproportionately higher for AA/B people relative to all other racial/ethnic groups (3). Similar patterns emerge by geography; compared to other geographic regions, residents of the southern US experience higher rates of HIV and AIDS diagnosis (1, 2). Thus, resolving the aforementioned racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV morbidity and mortality are clear national public health priorities (3–5).

Once diagnosed with HIV, being linked to and retained in HIV medical care, receiving and adhering to antiretroviral therapy and sustaining virological suppression are critical to minimize HIV morbidity and mortality as well as reduce new infections (6, 7). Although there is evidence indicating that there are no racial/ethnic disparities in retention in HIV care in the short-term (i.e., one-year after enrollment), AA/B PLWH are less likely to be retained in care over the long-term (8). When examining the intersection of geography and race, PLWH in the South, especially AA/B PLWH in the South, are less likely to be retained in care (8). Additionally, AA/B PLWH and PLWH in the South are less likely to achieve virological suppression relative to other racial/ethnic groups and geographic regions (9, 10). These disparities in the HIV care continuum are partially attributable to social determinants of health barriers across multiple levels ranging from individual to policy level factors (11). Some of these barriers include: 1) material deprivation, lack of health insurance, mental health challenges, substance use, stress (i.e., individual level); 2) racism and stigma (i.e., interpersonal level); 3) institutionalized racism in healthcare, homophobia and poor quality patient-provider relationships (i.e., organizational level); 4) distance and travel time from home to receipt of HIV care and residing in high-risk environments (i.e., neighborhood level); and 5) inconsistent funding for HIV care delivery (i.e., policy level) (10, 12–25).

High-risk neighborhoods are characterized by structural inequities (e.g., historical and current racism) that give rise to socioeconomic disadvantage, racial minority segregation in under-resourced communities, poor built environment infrastructure and crime (26–29). Prior work indicates that residing in high-risk neighborhoods is associated with delayed ART initiation, lower ART adherence, and increased mortality (26, 27, 30–32). AA/B people are significantly more likely to live in high-risk environments, which may contribute to racial disparities in adverse HIV outcomes (26, 30). The previously described barriers may preclude achievement of the 95-95-95 target by 2030 relating to diagnosis, receipt of ART and virological suppression, which are tantamount to the success of the domestic Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative (33–35). Although there are significant barriers to engagement in the HIV care continuum at multiple levels, protective and promotive resources, such as resilience, may mitigate some of these barriers for AA/B PLWH (36, 37).

Resilience refers to positive psychological, behavioral and/or social adaptation despite life’s adversities, whereby a person utilizes one’s own capacity as well as family and community resources to overcome adversities (14, 38, 39). Findings from review studies suggest that resilience resources are comprised of both an individual’s assets (e.g., self-efficacy, optimism, and emotion regulation) and external resources (e.g., social, economic, social support and neighborhood safety) (40–43). In the context of HIV management, resilience may promote engagement in positive health behaviors (e.g., retention in care, ART adherence) directly or buffer the impact of adversities (e.g., individual and/or neighborhood barriers) on physiological functioning and/or health behaviors (44, 45). Resilience is an emerging area of study in relation to HIV prevention and HIV disease management (43, 46). However, for studies that examine resilience among PLWH, the quantitative literature overwhelmingly focuses on individual level and a few interpersonal level resilience resources to the neglect of other potential resilience resources at meso and macro levels (i.e., organizational, neighborhood and policy levels) (37). This limitation may be a consequence of how resilience has been defined and measured mostly as an individual level phenomenon (47).

Given this gap in the literature, the objectives of this study are to: 1) use a mixed methods approach to identify multilevel resilience resources among AA/B PLWH who demonstrated progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (i.e., favorable clinic attendance adherence and viral load levels); and 2) examine whether the importance of these resilience resources differ by demographic and neighborhood risk environment factors. We focus on this subgroup of AA/B PLWH because they demonstrate evidence (i.e., favorable clinic attendance and viral load levels) of experiencing success in their HIV care. Achieving these study objectives will inform theories of resilience as well as measurement and multilevel resilience-based interventions for AA/B PLWH.

Methods

Study design

We used concept mapping for data collection and analysis. Concept mapping integrates qualitative and quantitative research methods to represent group-generated concepts and their interrelationships via a series of two-dimensional maps (48–50). We selected concept mapping because it: 1) integrates qualitative and quantitative methods; 2) aggregates the study participants’ combined thinking in a rigorous way; and 3) positions participants as active members in the research process (48, 51). Although we used the lowest level of community engagement (outreach) (52), the current study design prioritizes study participants as informed key stakeholders (e.g., participant-generated and ranked statements). Lastly, the concept mapping approach generates item content and psychometrically sound measures that could be used in future measure development (50, 53). We conducted concept mapping via in-person sessions with participants and used the Concept Systems Global Max web platform for analysis of the concept mapping data.

Setting

We conducted the concept mapping sessions at two medical clinics in the southeastern United States from June 2018 to August 2018. We received approvals to conduct human subjects research from the Brown University, University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Boards. Staff at each of the clinics read and reviewed consent forms with eligible participants and all participants provided informed written consent.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

PLWH were eligible for this study if they met several criteria. First, they had to be enrolled in either the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) 1917 Clinic Cohort (54) or the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research HIV Clinical Cohort (UCHCC) (55, 56). Second, they had to be AA/B and at least 18 years old. Third, they needed to have clinic appointments scheduled at one of the clinics during the study enrollment period (March 2018 to August 2018). Fourth, they needed to demonstrate evidence of progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum. Evidence was based on patients meeting the following criteria for the two years prior to March 1, 2018: 1) attended at least 75% of their scheduled clinic appointments; and 2) did not have two or more consecutive detectable HIV-1 viral load measurements. We selected this viral load criterion to align with the World Health Organization guideline (57). We did not include ART adherence as an eligibility criterion due to challenges in measuring ART adherence (58, 59). However, given the strong correlation between ART adherence as the behavioral determinant of viral suppression, we inferred that eligible participants would have high rates of ART adherence (60). Staff approached eligible PLWH who had completed a patient reported outcomes survey assessment during the designated enrollment period and who spoke, read, and understood English sufficiently to complete informed consent procedures and concept mapping. Enrolled participants received financial incentive(s) up to $100 for their participation (i.e., $50 per concept mapping session attended).

Data Collection

To ensure adequate power (n ≥ 40) for Step 3 of concept mapping, we aimed to enroll 50 participants (61). Of the 85 people invited to enroll, 48 (i.e., 56.5% response rate) enrolled and participated in at least one concept mapping session. The research team (study multiple principal investigators, project coordinator, clinic staff, and co-investigators) followed the concept mapping protocol outlined by Kane and Trochim (48, 49). Below, we describe the activities conducted for each step of the protocol.

Step 1. Preparing for Concept Mapping:

The research team developed the focus prompts (i.e., specific questions designed to generate statements from participants during Step 2 of concept mapping). We developed the focus prompts based on: 1) gaps in quantitative resilience studies with PLWH; 2) findings from qualitative studies with PLWH that highlighted HIV specific resilience resources across multiple systems; and 3) gaps in conceptualization of adversities (i.e., conceptualized solely as adversities related to living with HIV). All three focus prompts and explanatory text were written at a 7.2 or lower Flesch-Kincaid grade level. The three focus prompts and explanatory text were:

“We know that there are ongoing challenges in all people’s lives. What is it about you that helps you adapt to these challenges so that you are able to stick with your HIV care? This means things like going to your scheduled HIV clinic appointments and taking HIV medications as prescribed.”

“We know that there are ongoing challenges in all people’s lives. How do the people in your life help you adapt to these challenges so that you are able to stick with your HIV care? HIV care means things like going to your scheduled HIV clinic appointments and taking HIV medications as prescribed. When we say people, think about your family and friends. And, think about other people living with HIV, providers and other people in your life.”

“We know that there are ongoing challenges in all people’s lives. What is it about your neighborhood that helps you adapt to these challenges so that you are able to stick with your HIV care? HIV care means things like going to your scheduled HIV clinic appointments and taking HIV medications as prescribed. Please define neighborhood based on the area around where you live most of the time. Please think about the people, places and other things in your neighborhood.”

Step 2. Generating Ideas:

Using these focus prompts, participants generated ideas in small group or one-on-one sessions; although participants could meet in groups, they completed all generation of ideas independently. We accommodated any participant who requested individual sessions for confidentiality or other reasons. Twenty-seven participants completed this step. We held 5 group sessions with the number of participants ranging from 2 to 5 per session and we held 11 one-on-one sessions. A facilitator with a certification in concept mapping (Concept Systems Incorporated ®) and/or trained staff members led (or co-led) all sessions using a structured facilitator guide. During the sessions, we used a modified nominal group technique to generate ideas from participants in response to each of the three focus prompts in sequential order. The nominal group technique involves presenting a focus prompt, silently generating ideas, and using a round robin format for conveying, editing and prioritizing ideas (62, 63). In the round robin format, each participant provides one response at a time until all ideas are exhausted (62, 63). We streamlined the nominal group sessions by excluding the editing and prioritizing of ideas stages to reduce participant burden and to align with Steps 3 and 4 of concept mapping where these activities occur. We used the same modified nominal group technique during the one-on-one sessions with individual participants. We held 5 group sessions and 9 individual sessions. Participants achieved saturation of ideas during the latter group and individual sessions. During step 2, participants also self-reported their current housing status using the measure developed by Aidala and colleagues (64).

Upon conclusion of all Generating Ideas sessions, the research team used a three-stage process to review and refine the 365 statements generated by participants. First, one team member assigned a keyword(s) (i.e., a word taken directly from the statement) and a code (i.e., assigned based on the general theme of the statement) to each statement (e.g., code – “active patient”, keyword – “involved”; code – “acceptance”, keyword “not having shame”). After completing the keywording and coding processes, the team member used the keywords and codes to sort statements, separate compound ideas and determine relevance to the focus prompts. For example, in the first round of review, the reviewer deleted the majority of statements (92 statements) because they were redundant while others (23 statements) were excluded because they restated or were not relevant to the focus prompt. The team member also refined statements to improve clarity and to ensure that statement wording was at a seventh grade or lower reading level. After six iterations of review and refinement, 106 participant-generated statements were retained. Second, two team members conducted a search of publicly available resilience measures and added 10 unique resilience statements associated with HIV care continuum outcomes. Three team members with expertise in qualitative methods reviewed the Excel spreadsheet containing six iterations of data reduction; they conducted external reviews of the keyword and code assignments and of the refined statements. After this stage, 116 statements were retained. Last, three team members with expertise in resilience and one with expertise in psychometric testing independently completed the Content Validity Index to determine if the 116 statements reflected resilience resources (65). A tally of results was computed and next, consensus and discussion methods were used to resolve disagreements in ratings. At the conclusion of this review, 95 statements (81.8%) were retained in the final set. These 95 statements were uploaded to the Concept Systems Global Max web platform, were randomized, assigned a number in sequential order and then exported to Microsoft Word for printing of each individual statement on card stock for use during Step 3.

Step 3 Structuring Statements:

Participants sorted and rated the 95 statements that were generated during step 2. A total of 42 participants completed this step including 21 from the Generating Ideas step and 21 new participants. We enrolled new participants to yield a sufficient sample size of individual sorters and raters (48, 49). The newly enrolled participants also completed the brief housing survey described earlier. We held 6 group (participation ranged from 2 to 8 participants per session) and 18 one-on-one sessions.

The participants completed all structuring activities independently. First, each participant was instructed to read each statement and sort the statements into piles based on their perceived similarity in meaning. Although participants were free to sort the statements in any way, they were instructed to not create a miscellaneous pile (48, 49). Participants did not create labels for each of the sort piles because of concerns about respondent burden. Second, participants received a sheet listing each statement (n = 95). They rated each statement based on its relative importance to the other statements (5 = most important to 1 = least important compared to the other statements). Third, participants received another sheet listing the statements (n = 95). They rated each statement based on how easy they thought it would be to improve for people in a health program (4 = very easy to improve to 1 = not at all easy to improve).

Additional data obtained:

CD4 cell count and viral load level were retrieved from patients’ medical records. Neighborhood risk environment data were also obtained. Clinic staff used Esri ArcMap Geographic Information Systems Software (v. 10.5.1) to geocode participants’ residential addresses to US Census tracts to obtain measures of the neighborhood risk environment. We retrieved the census tract level 2018 Murder Rate Index and Assault Rate Index from Esri Business Analyst Online. For these indexes, Esri assigned the US a value of 100. When a study participant’s census tract had a value greater than 100 for a given index, it denoted an increased relative risk of murder or assault compared to the national level. Conversely, a value less than 100 denoted lower relative risk compared to the national level (66). We also obtained US Census (2017 American Community Survey Five-year estimates) derived measures of neighborhood risk environments including percent of residents ages 25 and older with less than a high school degree, percent unemployed and percent poverty. These data were also normed to the national level such that a Z-score = 1 indicated one standard deviation greater risk compared to the national level.

Data analysis and Interpretation

To examine participants’ demographics and health information, we calculated descriptive statistics (i.e., mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range for heavily skewed variables or frequencies and percentages). For the neighborhood risk environment variables, we used the median split to create categories of low or high risk for each variable that would be used in concept mapping analysis. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC).

We used the Concept Systems Global Max web platform (Concept Systems Incorporated, Ithaca, NY) to analyze the structuring data (i.e., Step 4. Analyzing Data). In these analyses, the sort data were represented as points on a two-dimensional map (X, Y coordinates); the closer the points, the more frequently these statements were sorted together (i.e., grouped as more similar in meaning) by participants on average. During the map creation, a stress value (ranging from 0 to 1) was generated to depict the goodness-of-fit of the mapped statements to the group sort data. Next, boundaries were drawn around the points; these boundaries represented how statements were grouped into conceptual themes. To create the point map and cluster boundaries, nonmetric, multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis were used (48, 49). The clusters that were closer together on the map indicated that statements in these clusters were more similar in meaning to one another. The clusters with larger boundaries reflected the grouping of more diverse statements. Conversely, the clusters with smaller boundaries represented the grouping together of less diverse, more focused statements. In post hoc analyses, we used the relative importance rating data to indicate the relative importance of each cluster compared to other clusters.

Step 5. Interpretation:

We used Kane and Trochim’s protocol (48, 49) to develop the final cluster solution. In brief, a cluster scenario ranging from 14 to 5 clusters was computed. Next, we used a structured guide to determine the interpretability and meaning of each cluster (48, 49). After arriving at a 12-cluster solution, the research team assigned cluster labels based on the conceptual meaning of each cluster. We conducted a series of post hoc analyses using the concept systems software. These post hoc analyses included pattern matches (i.e., Pearson’s correlation coefficient of clusters) to determine the strength of resilience-related cluster ratings of importance between participants based on demographics (age, gender and housing status) and neighborhood risk environment variables (high versus low-risk).

Results

Recruitment and participation in concept mapping

Eighty-five PLWH were invited to participate. Of those invited, 57 enrolled and 48 (i.e., 56.5% response rate and 96% of the original sample size goal of 50) participated in one or more of the concept mapping sessions. There was no considerable difference in age between study participants compared to those who enrolled, but did not attend any sessions (i.e., no-shows) [Wilcoxon Two-Sample Test, test statistic 247.5, p-value 0.775]. Also, there was no considerable difference in the proportion of females and males between no-shows and decliners versus study participants (data not shown) [Chi-square test statistic 3.45, p-value 0.063)]. Of the 48 study participants, 27 participated in the Generating Ideas step and 42 in the structuring step. Among those who provided structuring data, 2 did not provide any usable data; 1 participant’s data were excluded due to eligibility reasons post-study entry and the other participant’s data were excluded due to poor quality (e.g., all 95 statement ratings marked with the same response option).

Descriptive characteristics

Table I presents the descriptive characteristics of study participants. At enrollment, the median (IQR) age was 53 (22.5) and the sample was primarily male (56.2%). The median (IQR) CD4 cell count was 769 cells/mL (476) and all of the participants had HIV-1 RNA viral loads < 200 copies/mL.

Table I:

Descriptive characteristics of African American/Black adults living with HIV in the southern United States who participated in the concept mapping study (n = 48).

| Characteristic at study enrollment | Median (IQR), N (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 53 (22.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 27 (56.2) |

| Female | 21 (43.8) |

| Current Housing Status | |

| Stably housed | 35 (72.9) |

| Unstably housed | 6 (12.5) |

| Homeless | 2 (4.2) |

| Missing | 5 (10.4) |

| CD4 cell count (cells/mL) | 769 (476) |

| RNA (copies/mL) | |

| <40 | 47 (97.9) |

| >40 and <200 | 1 (2.1) |

| Neighborhood | |

| Disadvantage | 3.02 (4.24) |

| Low | 0.45 (4.24) |

| High | 4.69 (2.35) |

| Missing (n) | (4) |

| Neighborhood Assault | |

| Rate Index | 235 (346) |

| Low | 83 (77.0) |

| High | 429 (198.0) |

| Missing (n) | (4) |

| Neighborhood Murder | |

| Rate Index | 304 (635) |

| Low | 128 (143) |

| High | 763.5 (373) |

| Missing (n) | (4) |

Regarding current housing status, almost three-fourths were stably housed, 12.5% were unstably housed (e.g., reliance on temporary or transitional housing programs) and 4.2% were homeless. Forty-four participants’ (91.7%) residential addresses could be geocoded and linked with census tract data. Relative to all census tracts in the US, the study participants with geocoded and linked census data, resided in higher risk neighborhood environments. The median neighborhood disadvantage Z-score for these study participants was three standard deviations (median=3.02, IQR=4.24) above all US census tracts. The median neighborhood murder rate (median=304, IQR=635) was three times higher than the US and the median neighborhood assault rate (median=235, IQR=346) was almost two and a half times higher than the US.

Concept mapping results

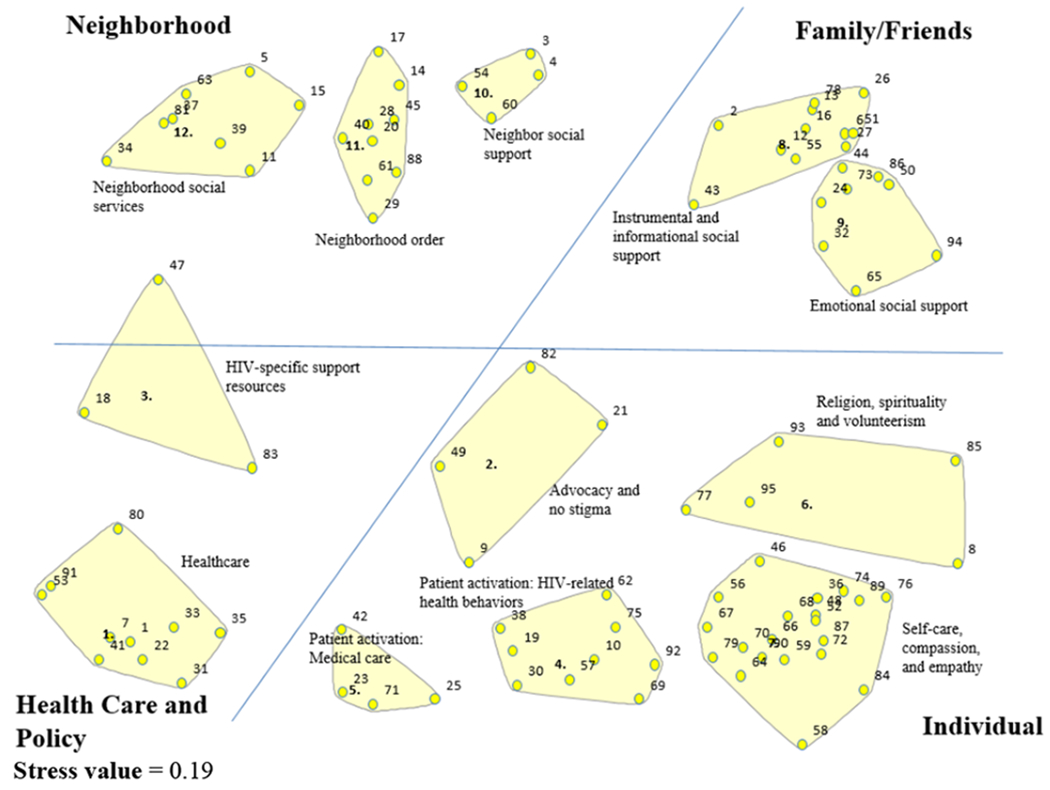

Figure 1a presents the stress value, orientation of clusters in the 12-cluster solution map and each cluster’s label and numbered points (i.e., statement numbers). The final map demonstrated good fit of the sort data; after 10 iterations, the final stress value was 0.19, which is better than the average stress value (i.e., 0.28) of concept mapping studies (61). The orientation of the 12 clusters reflects how the statements were sorted into clusters by participants, on average. We divided the map into four quadrants. The results are presented based on the orientation of the map quadrants in the clockwise direction. There are three resilience resource clusters at the neighborhood level, including: Neighborhood Social Services (cluster 12), Neighborhood Order (cluster 11) and Neighbor Social Support (cluster 10). At the interpersonal level (i.e., family/friends), there are two resilience resource clusters, including: Instrumental and Informational Social Support (cluster 8) and Emotional Social Support (cluster 9). There are five resilience resource clusters at the individual level, including: Advocacy and No Stigma (cluster 2), Religion, Spirituality and Volunteerism (cluster 6), Patient Activation: Medical Care (cluster 5), Patient Activation: HIV-Related Health Behaviors (cluster 4) and Self-Care, Compassion and Empathy (cluster 7). Lastly, there are two resilience resource clusters at the organizational/policy levels (i.e., healthcare), including: HIV-Specific Support Resources (cluster 3) and Healthcare (cluster 1).

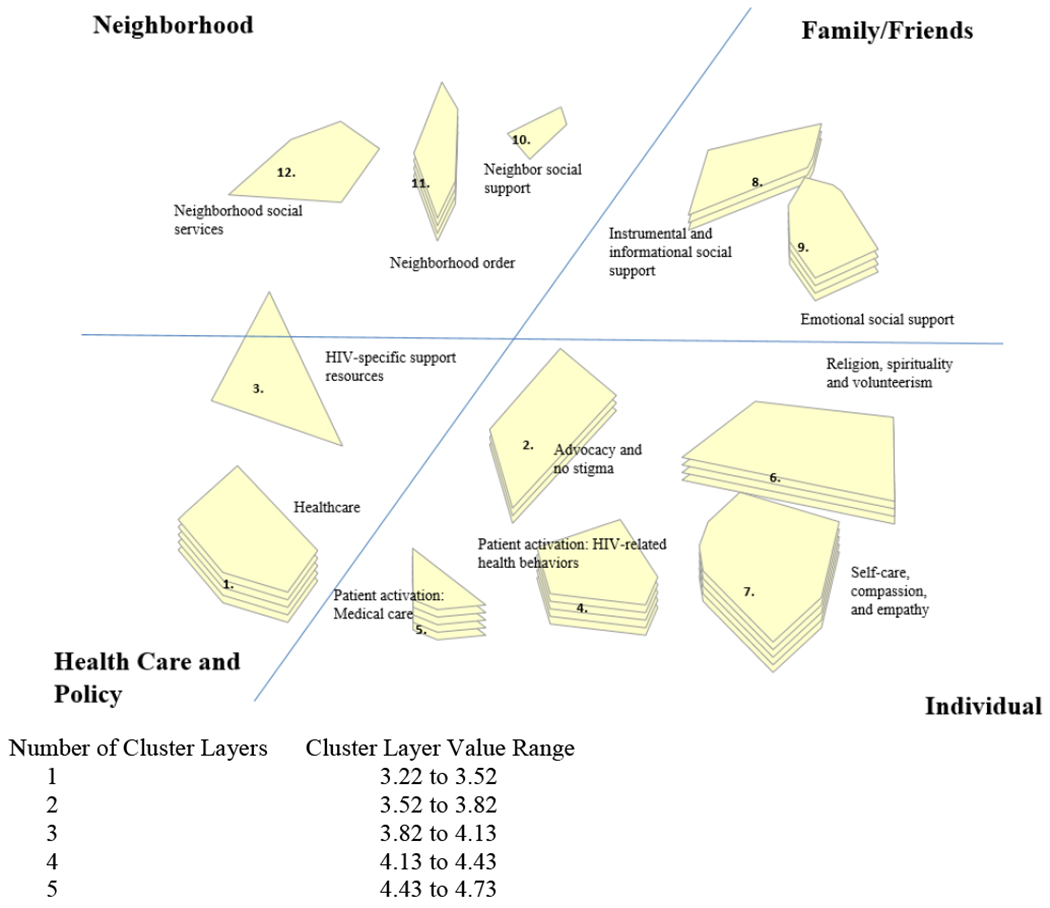

Figure 1.

12-Cluster solution map of multilevel resilience resource clusters for African American/Black adults living with HIV in the southern United States.

Figure 1a. Cluster orientation, statements within each cluster and cluster labels. The numbered points within each of the clusters correspond to the group participants’ average sorting of each statement into a cluster.

Figure 1b. Cluster orientation, cluster labels and cluster ratings of importance compared to the other clusters (1 = least important to 5 = most important). The cluster rating is denoted by layers; the more cluster layers, the higher average rating assigned to the cluster. The Cluster Layer Value Range provides the average cluster rating of importance for the number of cluster layers.

Figure 1b presents the rating of relative importance for each resilience resource cluster. The cluster’s layer(s) depicts its relative importance to the other clusters such that the more layers there are, the more important the cluster is relative to the other clusters. One cluster layer is the lowest rating of importance (values 3.22 to 3.52) and five cluster layers is the highest rating of importance (values 4.43 to 4.73). On average, participants rated the individual level resilience resource clusters such as Self-Care, Compassion and Empathy (cluster 7) and Patient Activation: Medical Care (cluster 5) as the most important (average ratings of 4.73 and 4.71, respectively). Participants rated two resilience resource clusters, Neighborhood Social Services (cluster 12) and HIV-Specific Support Resources (cluster 3), as the least important (average ratings of 3.30 and 3.22, respectively).

In Table II, the cluster labels, total number of statements within the cluster, cluster ratings of relative importance and the three highest rated statements of relative importance within each cluster are presented. The cluster labels reflect the overarching theme of the majority of statements within the cluster.

Table II:

Cluster names, cluster ratings of relative importance and the three highest rated statements of relative importance within each cluster for African American/Black adults living with HIV in the southern United States. Clusters are presented according to their orientation on the map.

| Cluster and Statement Ratings of Relative Importancea | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood Level | |

| Cluster 12: Neighborhood Social Services (n = 8 statements) | 3.30 |

| - There are church services in my neighborhood | 4.36 |

| - There are social support services in my neighborhood | 3.58 |

| - In my neighborhood there is bus transportation so that I can make it to my scheduled appointments | 3.38 |

| Cluster 11: Neighborhood Order (n = 9 statements) | 4.34 |

| - Being able to live in a safe neighborhood environment (like not high crime, police accessible) | 4.64 |

| - Living in a neighborhood where I do not see drugs or alcohol being used outside in my neighborhood | 4.54 |

| - Living in a neighborhood with safe housing | 4.53 |

| Cluster 10: Neighborhood Social Support (n = 4 statements) | 3.51 |

| - My neighbors are friendly | 4.15 |

| - Having neighbors who check in on me and look out for me | 3.68 |

| - When I need something, my neighbors are very helpful when they can be | 3.28 |

| Interpersonal Level: Family/Friends | |

| Cluster 8: Instrumental/Informational Social Support (n = 11 statements) | 3.88 |

| - Friends and family show sense of love and caringb | 4.38 |

| - Asking family members for help when needed | 4.21 |

| - Having close family members who ask what is going on in my life in generalb | 4.21 |

| Cluster 9: Emotional Social Support (n = 8 statements) | 4.33 |

| - My family helps by keeping me in their prayers | 4.69 |

| - My friends and family treat me like anyone else without HIV | 4.64 |

| - Having a strong support system such as family, friends, pastors or peer mentors | 4.59 |

| Individual Level | |

| Cluster 2: Advocacy/No Stigma (n = 4 statements) | 3.83 |

| - I have safe zones where I do not feel stigmatized | 4.46 |

| - I feel like I am an advocate to speak to people about living with HIV | 3.97 |

| - I am involved in the legislative system for funding of medication, Medicaid, and housing for people living with HIV | 3.51 |

| Cluster 6: Religion, Spirituality, Volunteerism (n = 5 statements) | 4.19 |

| - Knowing that this is a personal walk with God and me | 4.90 |

| - Helping others by volunteering | 4.26 |

| - Helping other people living with HIV (e.g., talking, giving encouragement, running errands) | 4.18 |

| Cluster 5: Patient Activation: Medical Care (n = 4 statements) | 4.71 |

| - Having good communication with my doctor | 4.92 |

| - Making taking my medications and attending my visits part of my routine | 4.72 |

| - Asking about any new breakthroughs and medicines with my doctor | 4.68 |

| Cluster 4: Patient Activation: HIV Health Behaviors (n = 9 statements) | 4.60 |

| - Having determination to outlive HIV, and not have it outlive me | 4.90 |

| - Keeping my medications with me when I am away from home | 4.79 |

| - Self-discipline by doing things such as taking medicine at a certain time, eating healthy, not drinking, using drugs or smoking | 4.72 |

| Cluster 7: Self-Care, Compassion and Empathy (n = 20 statements) | 4.73 |

| - My self-confidence | 4.95 |

| - Strong belief in Godb | 4.92 |

| - I accept that I am living with HIV | 4.90 |

| Organizational: Health Care | |

| Cluster 3: HIV-Specific Support Services (n = 3 statements) | 3.22 |

| - Having someone to help me work through my HIV -related depression | 3.69 |

| - I attend a support group with other people who are living with HIV | 3.00 |

| - Having community meetings about things like HIV | 2.95 |

| Cluster 1: Healthcare (n = 10 statements) | 4.47 |

| - Having programs that pay for HIV medications (Ryan White Program) | 4.95 |

| - HIV clinic employees treat me with kindness and compassion | 4.87 |

| - Getting positive feedback from my doctor when I make positive lifestyle changes | 4.74 |

Ratings of relative importance range from 1 = relatively unimportant to 5 = extremely important compared to the other statements.

These are outlier statements (i.e., not directly related to the main theme of the cluster), however, the cluster labels were unchanged because the labels reflect the overarching, emergent theme from the majority of statements within the cluster.

Post-hoc analyses compared the cluster ratings of relative importance between genders, age, housing status, and neighborhood risk environment (i.e., disadvantage, murder rate, and assault) groups. The correlations in cluster ratings between males versus females (r = 0.96), age ≥ 53 versus < age 53 (r = 0.92) and stably housed versus unstably housed (r = 0.92) were strong. Thirty-six participants had neighborhood risk environment data available. The cluster ratings between those in neighborhoods of high versus low disadvantage (r = 0.89), low murder rate versus high murder rate (r = 0.90) and low assault rate versus high assault rate (r = 0.97) were also strong. The strength of these correlations suggests that there was little variability in the ratings of perceived importance of these clusters between the comparison groups.

Discussion

This study used a community-engaged approach to identify multilevel resilience resources for progressing through stages of the HIV care continuum and to examine if the perceived importance of these resilience resources differed by demographics and neighborhood risk environments. Specifically, AA/B PLWH identified resilience resources at multiple levels including individual, interpersonal, organizational/policy and neighborhood levels (11). The perceived importance of these resilience resources was similar across participant demographics and neighborhood risk environments of varying levels. These findings highlight that when examining resilience in relation to outcomes along the HIV care continuum, researchers should examine resilience resources specific to AA/B PLWH and at multiple levels. Moreover, findings suggest multilevel interventions addressing resilience factors that span individual to policy level resources should be considered.

These findings add many novel contributions to the resilience and HIV literature. First, participants included a subset of AA/B PLWH with favorable clinic attendance adherence and viral load levels. This is important because AA/B PLWH are impacted disproportionately by barriers to progressing through the stages of the HIV care continuum, and the study design and sample highlight persons achieving success. Second, the overwhelming majority of the resilience resource items were generated by study participants and reflected the multilevel nature of resilience (47). Third, this study expands upon the current literature by framing the focus prompts with non-HIV specific adversities encountered by PLWH. Fourth, this work identified non-generic resilience resources specifically relevant for PLWH, which may have implications for progression through the HIV care continuum and potential interventions. Last, these results indicate that the importance of these resilience resources cut across demographics and neighborhoods of varying levels of risk.

Many of the individual level resilience resource clusters included psychological, behavioral (e.g., lifestyle and HIV-specific), religious, spiritual and volunteerism components. Some of the key psychological resilience resources centered on self-confidence, self-compassion and acceptance of living with HIV. Although study findings are mixed, these general themes are supported by the extant literature. For example, self-confidence for managing HIV care (e.g., health literacy) is associated with virological suppression in some studies (67), while the associations with ART or clinic appointment adherence are mixed (67–69). Other domains of self-confidence (e.g., managing mood or finding social support) are associated with ART adherence (68). Additionally, acceptance is an important resilience resource identified by the current study’s participants; the salience of this concept is supported in prior studies (70) where PLWH who accept their diagnosis are more engaged in care. Similar findings in other studies demonstrate that participants who do not accept their diagnosis are more likely to report difficulties with ART adherence because it serves as a reminder that they are living with HIV (71).

Other individual level clusters centered on HIV care behavioral factors. Specifically, patient-provider communication was one of the most important resilience resources. Across many qualitative studies, care seeking and progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum among AA/B and other PLWH hinge on the patient’s perceived quality and quantity of communications with their healthcare provider (44, 72, 73). Similarly, one of the resilience resources for progression included keeping abreast of research breakthroughs via communications with healthcare providers; similar accounts exist in the published literature (70). Participants in the current study also described creating habits to promote their adherence behaviors (e.g., taking medications at a certain time, using reminders) as a resilience resource. In studies of chronic disease management, habit strength predicts objectively measured medication adherence (74). Additionally, management of or abstinence from drug and alcohol use are characterized as resilience resources that facilitate progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (70). The emergence of these psychological and behavioral resilience resources may be critical for AA/B adults.

Another individual level cluster, Religion, Spirituality and Volunteerism, surfaced as an important resilience resource cluster for progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum. Religion and spirituality domains are identified consistently as important resources for AA/B PLWH across a number of studies, including for AA/B PLWH in the southeastern US (24, 75–77). In these studies, religion and spirituality are associated with progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (78). Also, volunteerism in general, and helping other PLWH specifically, helped study participants remain engaged in the HIV care continuum. This finding aligns with previous qualitative work that describes how helping other PLWH in clinic waiting rooms or as volunteers in HIV -related services (e.g., peer counseling and social service agencies) are motivators for PLWH’s own retention in care (73, 79), including over the long-term. Given the importance of religion and spirituality and the identification of volunteerism as resilience resources, future studies of resilience should include these resilience resources tailored to PLWH.

Two of the clusters focused on interpersonal level resilience resources. The majority of the highly rated interpersonal resilience resource statements included non-HIV-specific emotional, instrumental and informational social support. The critical role of general social support as a resilience resource is demonstrated in a majority of studies, including studies with AA/B PLWH, in relation to progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (37, 70, 72, 80). For example, Colsanti and colleagues (71) reported that PLWH who remained in care reported higher levels of social support from friends and family as well as more emotional support from family. In another study, participants identified instrumental support as a motivator to remain engaged in care (81). In the current study, additional resilience resources included the absence of HIV-related stigma in interpersonal relationships, which helped participants remain engaged in HIV care. A systematic review of factors contributing to retention in care among Black women indicated that experiences of HIV-related stigma in interpersonal relationships are barriers to progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (44, 82). Thus, general and HIV-specific social support, as well as non-HIV stigma-related resilience resource items, may be worthwhile to include when examining HIV care continuum outcomes or developing interventions among groups like AA/B PLWH.

Although the focus prompts for this study did not inquire about organizational or policy level resilience resources, participants identified several related to healthcare. Some of the most important resilience resources referenced policies that facilitate health care access (e.g., Ryan White), the climate of the clinic and the presence of HIV-specific support services. In previous studies of older adult AA/B PLWH, a lack of prescription drug coverage operated as a barrier to ART adherence. Systematic reviews (83) and other primary studies also demonstrate the critical role of polices (e.g., expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and Ryan White) (84) supportive of progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum. Aside from these policy level factors, several of the resilience resources depended upon the climate of the healthcare organization and provider behaviors. For example, participants indicated that being treated with kindness and compassion from healthcare staff, as well as receiving positive feedback from providers, helped them remain in care. Indeed, a positive healthcare climate (e.g., attitudes/behaviors of healthcare providers) predicts progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum (18, 24, 44, 81). Lastly, some of the other resilience resources, though not highly rated, centered on support for HIV-related depression and support groups. These findings are similar to those of Rajabiun et al., who identified psychological challenges of living with HIV (e.g., HIV-related depression) as barriers to care (70).

Lastly, participants identified neighborhood level resilience resources. The focus on resilience resources, even in high-risk neighborhoods, contrasts with the majority of the neighborhood research within the HIV literature. With some exceptions [e.g., (30, 85–87)], the majority of neighborhood level studies solely examine risk environments in relation to adverse HIV care continuum outcomes. Some research findings indicate that higher risk environments (e.g., high levels of neighborhood economic deprivation) are associated with lower likelihood of having a current ART prescription and low virological suppression (21, 88). However, our findings demonstrate that despite living in high-risk neighborhood environments where more than half of participants reside in more economically disadvantaged and higher crime neighborhoods compared to the US, AA/B PLWH still identified resilience resources (e.g., neighbor social support, social services and physical and social order) that helped them remain engaged in care. Some of these neighborhood resilience resources, such as the presence and utilization of community-based social service organizations, bus transportation and safe housing, have been identified in other studies as resilience resources for better HIV care continuum outcomes (37, 73, 86, 89–91). A previous systematic review identified the dearth of resilience studies that included neighborhood level resilience resources among PLWH (37). Based on the current findings, it appears that the inclusion of these neighborhood resilience resources in future studies and measures is warranted.

There are some limitations to the current study. We relied on medical records for gender data instead of self-report and to our knowledge, there were no transgender participants in the study. Inclusion of transgender participants may have yielded additional resilience resource statements that could inform future multilevel resilience measures and/or intervention efforts with AA/B PLWH. Also, we did not collect data on sexual orientation so it is unclear if the importance of resilience resource clusters might differ for sexual orientation subgroups. The data collection was limited to only two clinics in the South; thus, the resilience items generated (e.g., the large number of religiosity/spirituality items) may not be applicable to other AA/B PLWH in other regions of the US (92). Additionally, one of the spiritual statements, “strong belief in God,” was an outlier in cluster 7 and fit better with the theme of cluster 6; in a future, more formal measure development study, this item may very well load onto a Religion, Spirituality and Volunteerism subscale. Although participants generated healthcare-specific resilience resource statements, it is possible that participants would have generated more items related to this theme if we had included a focus prompt about organizational resilience resources. Additionally, the median age of study participants slanted toward middle age (i.e., median age 53) (93). However, across racial/ethnic groups, PLWH ages 40 and older are more likely to be retained in care relative to other age groups. As such, the older ages of participants in the current study align with these general findings (8).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, there are numerous strengths of this study, which we described earlier. The current study findings represent one phase of ongoing work (i.e., measure development and longitudinal study) to examine multilevel resilience resources among AA/B PLWH in relation to progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum. The scientifically rigorous identification of multilevel resilience resources, in conjunction with AA/B PLWH, may yield new multilevel theories, conceptualizations and measurement models. If multilevel resilience resources predict progression through the stages of the HIV care continuum for AA/B PLWH, these findings could inform future research, practice and policy efforts. Lastly, the identification of specific resilience resources supportive of favorable HIV outcomes will lead to asset-based (i.e., resilience-building) multilevel interventions that address inequalities in HIV-related outcomes experienced disproportionately by AA/B PLWH (14, 37).

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH112386. The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors also thank the clinic staff, the GIS data analyst and student for their assistance with this study and manuscript.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH112386. One hundred percent of the project costs ($559,735) are financed with Federal money. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest: Authors Akilah Dulin and Chanelle Howe are the multiple principal investigators of Award Number R01MH112386 for which this research was conducted. Authors Valerie Earnshaw, Sannisha Dale, Michael Carey, Joseph Fava, Michael Mugavero and Sonia Napravnik are co-investigators of this award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Ethics Approval: The questionnaire and methodology for this study received approval from the following institutional review boards: Brown University (Approval No. 1707001833), University of Alabama at Birmingham (Approval No. IRB-300001171) and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (Approval No. 17-2584)

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data/Code Availability: N/A

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010 - 2015. 2018. Report No.: 23.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Preliminary). 2018.

- 3.Lesko CR, Cole SR, Miller WC, Westreich D, Eron JJ, Adimora AA, et al. Ten-year Survival by Race/Ethnicity and Sex Among Treated, HIV-infected Adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(11):1700–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010.

- 5.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Update of 2014 Federal Actions to Achieve National Goals and Improve Outcomes Along the HIV Care Continuum. 2014.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Care Continuum 2016. [updated December 30, 2016 Available from: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Treatment as Prevention 2019. [updated November 12, 2019 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html.

- 8.Anderson AN, Higgins CM, Haardorfer R, Holstad MM, Nguyen MLT, Waldrop-Valverde D. Disparities in Retention in Care Among Adults Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beer L, Bradley H, Mattson CL, Johnson CH, Hoots B, Shouse RL, et al. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Antiretroviral Therapy Prescription and Viral Suppression in the United States, 2009-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(4):446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimmel AD, Masiano SP, Bono RS, Martin EG, Belgrave FZ, Adimora AA, et al. Structural barriers to comprehensive, coordinated HIV care: geographic accessibility in the US South. AIDS Care. 2018;30(11):1459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bofill L, Waldrop-Valverde D, Metsch L, Pereyra M, Kolber MA. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with appointment attendance among HIV-positive outpatients. AIDS Care. 2011;23(10):1219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dale SK, Dean T, Sharma R, Reid R, Saunders S, Safren SA. Microaggressions and Discrimination Relate to Barriers to Care Among Black Women Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(4):175–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–36. doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fullilove RE. African Americans, Health Disparities and HIV/AIDS: Recommendations for Confronting the Epidemic in Black America. National Minority AIDS Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Napravnik S, Kaufman JS, Adimora AA, Elston B, et al. The role of at-risk alcohol/drug use and treatment in appointment attendance and virologic suppression among HIV+ African Americans AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(3):233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leserman J, Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fordiani JM, Balbin E. Stressful life events and adherence in HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(5):403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 Suppl 2:S238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pecoraro A, Royer-Malvestuto C, Rosenwasser B, Moore K, Howell A, Ma M, et al. Factors contributing to dropping out from and returning to HIV treatment in an inner city primary care HIV clinic in the United States. AIDS Care. 2013;25(11):1399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridgway JP, Almirol EA, Schmitt J, Schuble T, Schneider JA. Travel Time to Clinic but not Neighborhood Crime Rate is Associated with Retention in Care Among HIV-Positive Patients. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3003–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shacham E, Lian M, Onen NF, Donovan M, Overton ET. Are neighborhood conditions associated with HIV management? HIV Med. 2013;14(10):624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traeger L, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Risk factors for missed HIV primary care visits among men who have sex with men. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2012;35(5):548–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiewel EW, Borrell LN, Jones HE, Maroko AR, Torian LV. Neighborhood Characteristics Associated with Achievement and Maintenance of HIV Viral Suppression Among Persons Newly Diagnosed with HIV in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaston GB, Alleyne-Green B. The impact of African Americans’ beliefs about HIV medical care on treatment adherence: a systematic review and recommendations for interventions. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geter A, Herron AR, Sutton MY. HIV-Related Stigma by Healthcare Providers in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(10):418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold M, Hsu L, Pipkin S, McFarland W, Rutherford GW. Race, place and AIDS: the role of socioeconomic context on racial disparities in treatment and survival in San Francisco. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.019. Epub May 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–24. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper HL, Linton S, Kelley ME, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, Chen YT, et al. Risk Environments, Race/Ethnicity, and HIV Status in a Large Sample of People Who Inject Drugs in the United States. PloS one. 2016;11(3):e0150410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunn A, Yolken A, Cutler B, Trooskin S, Wilson P, Little S, et al. Geography should not be destiny: focusing HIV/AIDS implementation research and programs on microepidemics in US neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):775–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4): 197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 90–90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014;JC2684.

- 34.United States Agency for International Development. Statement: 2016 United Nations political declaration on ending AIDS sets world on the fast-track to end the epidemic by 2030. 2016.

- 35.Levi J, Raymond A, Pozniak A, Vernazza P, Kohler P, Hill A. Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. Bmj Glob Health. 2016;1(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dale SK, Safren SA. Resilience takes a village: black women utilize support from their community to foster resilience against multiple adversities. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup5):S18–S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dulin AJ, Dale SK, Earnshaw VA, Fava JL, Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, et al. Resilience and HIV: a review of the definition and study of resilience. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup5):S6–S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. European Psychologist,. 2013;18:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unger M Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38(2):218–35. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Distelberg BJ, Martin AS, Borieux M, Oloo WA. Multidimensional Family Resilience Assessment: The Individual, Family, and Community Resilience (IFCR) Profile. J Hum Behav Soc Envi. 2015;25(6):552–70. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin AS, Distelberg B, Palmer BW, Jeste DV. Resilience and Aging: Development of the Multilevel Resilience Measure. Am J Geriat Psychiat. 2013;21(3):S106–S7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schetter CD, Dolbier C. Resilience in the Context of Chronic Stress and Health in Adults. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5(9):634–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodward EN, Banks RJ, Marks AK, Pantalone DW. Identifying Resilience Resources for HIV Prevention Among Sexual Minority Men: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(10):2860–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geter A, Sutton MY, McCree DH. Social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and care among black women living with HIV infection: a systematic review: 2005-2016. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2018;30(4):409–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dale S, Cohen M, Weber K, Cruise R, Kelso G, Brody L. Abuse and Resilience in Relation to HAART Medication Adherence and HIV Viral Load Among Women with HIV in the United States. Aids Patient Care St. 2014;28(3):136–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: theory and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw J, McLean KC, Taylor B, Swartout K, Querna K. Beyond Resilience: Why We Need to Look at Systems Too. Psychol Violence. 2016;6(1):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane MT, W. M. K. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kane MT, W. M. Concept mapping for applied social research In: Bickman LR, D. J., editor. The Sage Handbook of Applied Social Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosas SR, Camphausen LC. The use of concept mapping for scale development and validation in evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(2):125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldman AW, Kane M. Concept mapping and network analysis: an analytic approach to measure ties among constructs. Eval Program Plann. 2014;47:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of community engagement. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. Contract No.: NIH Publication No. 11-7782. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dulin-Keita A, Clay O, Whittaker S, Hannon L, Adams IK, Rogers M, et al. The influence of HOPE VI neighborhood revitalization on neighborhood-based physical activity: A mixed-methods approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;139:90–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mugavero MJ, Lin H-Y, Allison JJ, Willig JH, Chang P-W, Marler M, et al. Failure to Establish HIV Care: Characterizing the “No Show” Phenomenon. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45(1):127–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Napravnik S, Eron JJ, McKaig RG, Heine AD, Menezes P, Quinlivan E. Factors associated with fewer visits for HIV primary care at a tertiary care center in the SoutheAstern U.S. AIDS Care. 2006;18(sup1):45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Napravnik S, Eron JJ. Enrollment, retention, and visit attendance in the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research HIV clinical cohort, 2001-2007. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(8):875–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2013. [PubMed]

- 58.Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Safren SA, Mugavero MJ, Willig JH, et al. Evaluation of the single-item self-rating adherence scale for use in routine clinical care of people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):307–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Giordano TP. Validity of self-report measures in assessing antiretroviral adherence of newly diagnosed, HAART-naive, HIV patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12(5):244–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glass T, Myer L, Lesosky M. The role of HIV viral load in mathematical models of HIV transmission and treatment: a review. Bmj Glob Health. 2020;5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(2):236–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gallagher M, Hares T, Spencer J, Bradshaw C, Webb I. The Nominal Group Technique - a Research Tool for General-Practice. Fam Pract. 1993;10(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delp P, Pasitam. Systems tools for project planning. Bloomington, Ind.: Pasitam; 1977. xxvi, 274 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):101–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polit DF, Beek CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esri. Crime summary sample report (dated June 20, 2019). 2019.

- 67.Rebeiro PF, McPherson TD, Goggins KM, Turner M, Bebawy SS, Rogers WB, et al. Health Literacy and Demographic Disparities in HIV Care Continuum Outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2604–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reif S, Proeschold-Bell RJ, Yao J, Legrand S, Uehara A, Asiimwe E, et al. Three types of self-efficacy associated with medication adherence in patients with co-occurring HIV and substance use disorders, but only when mood disorders are present. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tyer-Viola LA, Corless IB, Webel A, Reid P, Sullivan KM, Nichols P, et al. Predictors of medication adherence among HIV-positive women in North America. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(2):168–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajabiun S, Mallinson RK, McCoy K, Coleman S, Drainoni ML, Rebholz C, et al. “Getting me back on track”: the role of outreach interventions in engaging and retaining people living with HIV/AIDS in medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S20–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colasanti J, Stahl N, Farber EW, del Rio C, Armstrong WS. An Exploratory Study to Assess Individual and Structural Level Barriers Associated With Poor Retention and Re-engagement in Care Among Persons Living With HIV/AIDS. Jaids-J Acq Imm Def. 2017;74:S113–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jemmott JBZJ; Croom M; et al. Barriers and facilitators to engaging african american men who have sex with men in the HIV care continuum: a theory-based qualitative study J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(3):352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Remien RH, Bauman LJ, Mantell JE, Tsoi B, Lopez-Rios J, Chhabra R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement of vulnerable populations in HIV primary care in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69 Suppl 1:S16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Assessing theoretical predictors of long-term medication adherence: Patients’ treatment-related beliefs, experiential feedback and habit development. Psychol Health. 2013;28(10):1135–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dalmida SG, McCoy K, Koenig HG, Miller A, Holstad MM, Thomas T, et al. Examination of the Role of Religious and Psychosocial Factors in HIV Medication Adherence Rates. J Relig Health. 2017;56(6):2144–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parsons SK, Cruise PL, Davenport WM, Jones V. Religious beliefs, practices and treatment adherence among individuals with HIV in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poteat T, Lassiter JM. Positive religious coping predicts self-reported HIV medication adherence at baseline and twelve-month follow-up among Black Americans living with HIV in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Care. 2019;31(8):958–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Medved Kendrick H Are religion and spirituality barriers or facilitators to treatment for HIV: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care. 2017;29(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kempf MC, McLeod J, Boehme AK, Walcott MW, Wright L, Seal P, et al. A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to retention-in-care among HIV-positive women in the rural southeastern United States: implications for targeted interventions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(8):515–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sangaramoorthy T, Jamison A, Dyer T. Older African Americans and the HIV Care Continuum: A Systematic Review of the Literature, 2003–2018. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):973–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yehia BR, Stewart L, Momplaisir F, Mody A, Holtzman CW, Jacobs LM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to patient retention in HIV care. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lipira L, Williams EC, Huh D, Kemp CG, Nevin PE, Greene P, et al. HIV-Related Stigma and Viral Suppression Among African-American Women: Exploring the Mediating Roles of Depression and ART Nonadherence. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;23(8):2025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ginnosar T, Van Meter L, Ali Shah SF, et al. Early impact of the patient protection and affordable care act on people living with HIV: a systematic review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(3):259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eaton EF, Mugavero MJ. Editorial Commentary: Affordable Care Act, Medicaid Expansion … or Not: Ryan White Care Act Remains Essential for Access and Equity. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):404–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ransome Y, Thurber KA, Swen M, Crawford ND, German D, Dean LT. Social capital and HIV/AIDS in the United States: Knowledge, gaps, and future directions. SSM Popul Health. 2018;5:73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, Jin H, Chaudoir SR. HIV stigma and physical health symptoms: do social support, adaptive coping, and/or identity centrality act as resilience resources? AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ransome Y, Kawachi I, Dean LT. Neighborhood Social Capital in Relation to Late HIV Diagnosis, Linkage to HIV Care, and HIV Care Engagement. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):891–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, Voytek CD, Fiore DJ, Blank M, et al. Individual and community factors associated with geographic clusters of poor HIV care retention and poor viral suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69 Suppl 1:S37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Rueda S, et al. Housing Status, Medical Care, and Health Outcomes Among People Living With HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sprague CS, S. E. Understanding HIV care delays in the US South and the role of the social-level in HIV care engagement/retention: a qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014;13(28). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wiewel EW, Borrell LN, Maroko AR, Jones HE, Torian LV, Udeagu CC. Neighborhood social cohesion and viral suppression after HIV diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2018:1359105318810088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Brown RK. African American Religious Participation. Rev Relig Res. 2014;56(4):513–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lachman ME, Teshale S, Agrigoroaei S. Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. Int J Behav Dev. 2015;39(1):20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]