Abstract

Objective:

Discrepancies between self-reported and actual adherence to biomedical HIV interventions is common and, in clinical trials, can compromise the integrity of findings. One solution is to monitor adherence biomarkers, but it is not well understood how to navigate biomarker feedback with participants.

Methods:

We surveyed 42 counselors and interviewed a subset of 22 to characterize their perspectives about communicating with participants about residual drug levels, a biomarker of adherence, within MTN-025/HOPE, a Phase 3b clinical trial of a vaginal ring to prevent HIV.

Results:

When biomarkers indicated low drug levels that mismatched high self-report, counselors encountered barriers to acceptance and comprehension among participants. However, discrepancies between low self-report and higher drug levels generally stimulated candor. Women recollected times they had not used the product and disclosed problems that counselors thought might otherwise have remained forgotten or concealed. Navigating conversations toward HIV prevention was easier at mid-range drug levels and when women indicated motivation to prevent HIV.

Conclusions:

Biomarker ratings offered a somewhat objective measure of adherence and protection that counselors perceived as meaningful to participants and as a valuable catalyst for conversations about HIV prevention. However, communication about biomarkers required that counselors navigate emotional barriers, respond skillfully to questions about accuracy, and pivot conversations non-judgmentally away from numerical results and toward the priority of HIV prevention. Findings suggest a role for biomarker feedback in future clinical trials as well as other clinical contexts where biomarkers may be monitored, to motivate disclosure of actual adherence and movement toward HIV prevention.

Keywords: drug detection monitoring, HIV prevention, microbicides, HIV/AIDS, personalized adherence feedback

Resumen

Objective:

Discrepancias entre la adherencia auto-reportada y la verdadera a intervenciones biomédicas de VIH pueden comprometer los ensayos clínicos. Una solución es monitorear la adherencia por medio de ensayos biológicos, pero no se entiende bien cómo comunicar estas medidas a los participantes.

Methods:

En MTN-025/HOPE, un ensayo fase 3b de un anillo vaginal para prevenir VIH, encuestamos a 42 consejeros de adherencia y entrevistamos a un subconjunto de 22 para caracterizar sus perspectivas sobre comunicar una medida objetiva de adherencia al anillo, el nivel residual de droga (RDL por sus siglas en inglés).

Results:

Los consejeros reportaron que los participantes apreciaron la retroalimentación del RDL como una indicación de su protección de VIH. Niveles más altos de droga estimularon euforia y alivio mientras niveles mas bajos resultaron en desilusión. Una postura no crítica y el apoyo a la autonomía de elegir otras alternativas al anillo promovieron divulgacion de las razones por la falta de adherencia. Hablar del monitoreo de RDL como “protección” en vez de “adherencia” ayudó a cambiar el enfoque desde resultados numéricos hasta la meta mayor del ensayo de prevenir el VIH.

Conclusion:

Personalizar la retroalimentación de medidas objetivas de adherencia requiere una conversación cuidadosa para minimizar las actitudes defensivas. La retroalimentación personalizada también se puede implementar de forma que motive la divulgación de la falta de adherencia y evoque un compromiso a prácticas de prevención. Enfatizar las motivaciones de las mujeres a prevenir el VIH, en vez de los resultados numéricos, puede incentivar a los usuarios consistentes a continuar y a los usuarios inconsistentes a usar métodos alternativos de prevención.

Introduction

Clinical trials of biomedical HIV interventions have detected discrepancies between self-report and objective, pharmacokinetic measures of actual medication use [1-5]. These discrepancies, even in trials that integrated adherence counseling [6,7], have led to recommendations that future investigations rely on objectives measures rather than solely self-report [8,9].

Objective biological measures hold the promise of protecting the primary aim of clinical trials, to discern and adjust for statistical differences across study arms – but may also promote actual product use. Among participants who understand that they are being monitored, extrinsic motivation to adhere may increase [10], and drug detection feedback may stimulate disclosure of relevant difficulties in product use that interfere with adherence [11]. This latter point is salient for clinical trials because, if left unmentioned, these difficulties could obscure opportunities to shift product design or delivery in ways that are meaningful for their intended users [12] – and, ultimately, could compromise the external validity of products intended for real-world use [10,13-16], However, little is empirically known about how to share drug detection data in ways that elicit disclosure of actual product use or that promote adherence, rather than defensiveness.

If communicated in confrontational ways, drug detection may alienate participants who perceive monitoring as policing their behavior [17]. People generally report compelling reasons to withhold medically relevant information (e.g., to protect against embarrassment and judgment) [18]. This includes withholding reports of nonadherence in clinical trials, when participants fear repercussions or want to avoid additional counseling that they perceive as burdensome [15]. Counselors too experience worries about trying to discuss nonadherence in ways that do not provoke greater defensiveness from their clientele [19,20]. Guidance outside of HIV clinical trials about giving sensitive feedback [21] includes advice that counselors adopt a neutral stance and communicate information nonjudgmentally [21,22] to minimize the likelihood of conflict [23]. However, adherence counseling protocols within clinical trials rarely specify how to share adherence data from biological assays [24-26] and none provide empirical support for their recommended practices. To date, studies have also solely examined challenges to adherence from the perspective of study participants, despite that counseling relies on a relationship that is, at very least, dyadic [27]. The perspectives of counselors, who face both client reluctance to disclose and their own difficulties navigating adherence feedback, may provide important guidance about best practices. Their perspectives may be useful both within future clinical trials and more broadly, in other contexts where biological assays are routinely available, like clinical services.

Methods

To document perspectives on drug monitoring conversations, we surveyed and interviewed counselors within the Microbicide Trials Network Study 025, HIV Open-label Prevention Extension (MTN-025/HOPE), a Phase 3B study which aimed to characterize safety and adherence to a dapivirine vaginal ring. MTN-025/HOPE did not prioritize use of the vaginal ring, but instead supported women’s autonomy to choose any combination of methods to prevent HIV. We invited counselors from this larger study to participate in an online survey and subsequent in-depth interviews as part of an ancillary study, Implementation of “Options in HIV Prevention Counseling” in HOPE. Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committees at all participating sites and the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved all study procedures.

Counseling Protocol

For MTN-025/HOPE, all counselors underwent extensive training in Options Counseling, a novel adherence intervention based in motivational interviewing and designed specifically to support HIV prevention in the context of an open-label trial for the vaginal ring. Informed by previous work on the discrepancy between self-report and adherence biomarkers [1-4,28] as well as recommended practices from Motivational Enhancement Therapy [19,21], Options Counseling intended to improve both adherence and open communication about adherence to better understand and support participant decisionmaking regarding HIV prevention. Counselors received two days of in-person training, materials to support fidelity (a detailed manual, a tabletop flipchart for easy reference, and demonstration videos), and monthly coaching calls and fidelity monitoring. Options Counseling is described in more detail elsewhere [29].

With women who elected to use the ring, Options Counseling involved discussing residual drug levels (RDLs). Participants were to return used rings at each study visit and these rings then underwent laboratory-based assessment [4] to determine how much residual drug remained within each device. The RDL was a numerical approximation of the extent of dapivirine absorption in each woman in the past month, and therefore served as a marker of participants’ level of adherence and HIV protection.

For counseling, we conceptualized the RDLs as “Protection Levels,” ranging from 0 (No Protection) to 3 (High Protection). The RDL for each ring was determined using a rate derived from an algorithm considering the amount of drug originally loaded within the ring, the residual amount remaining after use, and the number of days a woman had the ring: rate = (ring load level - residual ring level)/(date collected - date dispensed). When more than one ring was returned at a visit, thus making it difficult to determine each ring’s dispensation and collection dates, 28 days was used as the denominator. Rates were then ranked: rate ≤ .05 = No Protection (RDL 0); .05 < rate < .107 = Low Protection (RDL 1); .107 ≤ rate < .138 = Moderate Protection (RDL 2); rate ≥ .138 = High Protection (RDL 3). RDL results were not 100% accurate, but multiple low RDLs in a row could be interpreted as a strong indicator of non-adherence, misuse, or sparing use.

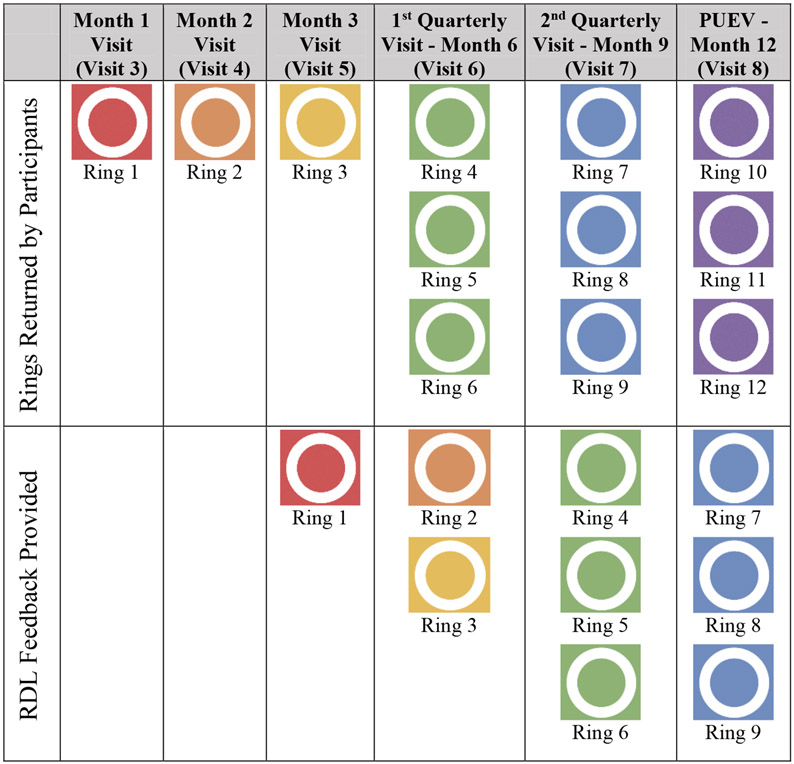

Starting at Month 3, counselors communicated RDL feedback from one or more rings returned at previous visits (Fig. 1). Options Counseling for RDL conversations was illustrated by flipchart sections counselors used during sessions. The protocol directed counselors, before sharing results, to communicate a non-judgmental stance regarding adherence, and specifically to acknowledge the very human difficulty of achieving perfect adherence. Before disclosing individual results, counselors first defined each possible 0-3 RDL. They framed this educational component by stating that results may not be 100% accurate but could help participants understand their individual level of HIV protection from using the ring, including patterns over time as multiple rings are evaluated from previous visits. These ratings and patterns could then inform women’s decisions to use the ring to improve or maintain their HIV protection, or to discontinue ring use to pursue alternative prevention strategies. Counselors then disclosed each ring’s RDL. Counselors emphasized autonomy by inviting participants to share their thoughts and feelings about their level of protection, and the implications for remaining HIV-negative. For women receiving a 0 RDL or a pattern across returned rings of low RDLs or inconsistent RDLs, counselors were instructed to assess participant reactions and possible obstacles to ring use, and to remind participants that it was their decision whether they wanted to continue to use the ring, as the study welcomed switching to another HIV prevention method women might find more suitable. If there was no possible explanation for the discrepancy between high self-reported use and a low or inconsistent RDL pattern across returned rings, counselors were instructed to encourage women to wait until their next RDL feedback to make more informed decisions about future ring use and, in the meantime, to consider increasing their HIV protection level with additional options. Whether participants had used the ring or not, counselors guided a discussion of successes and obstacles in preventing HIV and refinement of plans according to the options that participants felt best suited their circumstances.

Figure 1.

Feedback Timeline for Residual Drug Levels (RDLs)

Procedures for Ancillary Study among MTN-025/HOPE Counselors

We recruited across the 14 study sites within MTN-025/HOPE by emailing only those counselors who had completed at least ten counseling sessions (n = 60), introducing our ancillary study as voluntary. We then emailed an individualized link to an online consent form and survey. Counselors could opt to participate in just the online survey but could also indicate an interest in being interviewed at a later date.

The brief online survey comprised demographic questions and assessments of counseling experiences. For interviews, we randomly selected up to two interested counselors from each MTN-025/HOPE site (two sites in Malawi, eight in South Africa one in Uganda, and three in Zimbabwe). Once selected, counselors were sent an online consent form for the interview. Two interviewers based in New York City conducted the interviews from July 2018 to May 2019. One was new to MTN-025/HOPE and unfamiliar to the counselors; the other had been part of the larger trial but had had minimal counselor contact. Interviews lasted 45-60 minutes, conducted through a telephone conference line. All interviews were conducted in English, transcribed, and then checked for accuracy and to redact identifying information.

Measurement

The online survey asked questions about Options Counseling, including two items about RDL conversations. Counselors were asked to estimate how many participants experienced difficulty understanding “General information about drug level results” and “Participant’s [own] residual drug level results.” Likert scale categories ranged from 1 Few Participants to 4 Most Participants.

Interviewers followed a written guide about overall impressions of RDL conversations and specific aspects of conversations based on the RDL (i.e., 0, 1, 2 or 3).

Data Analysis

We analyzed descriptive statistics from the online survey in SPSS 25 [30].

The lead investigator and team developed a codebook based on the interview guide, which included code definitions and exclusion/inclusion criteria. Two independent team members used NVivo (v11) [31] to code transcripts and met periodically to assess intercoder reliability and to resolve discrepancies by consensus.

To identify themes related to RDL conversations, the first author extracted coding reports for each drug level and highlighted content related to participant reactions, counselor reactions, and counseling strategies. This then formed the basis of a matrix analysis, with separate columns for the aforementioned topics, repeated as subheadings beneath each RDL as a larger heading, with rows for each counselor’s response. The first author identified themes within the matrix by reading within each RDL’s column across participants and then within the same participant row across RDLs. The first author presented findings for review within the larger research team.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Among those emailed (n = 60), 6 counselors actively declined for unknown reasons and 12 did not respond. Of the non-responders, 6 had resigned from their positions and 4 had not conducted sessions in over a year. Among those randomly selected for interviews (n = 24), 2 were not interviewed after they missed three scheduled interviews.

Counselor demographics are documented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of ancillary study counselors (n = 42)

| Survey (n = 42) | Interview (n =22) | |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Education Completed in Years | 16.5 (2.8) | 17.1 (1.8) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 3 (7.1) | 1 (4.5) |

| Female | 39 (92.9) | 21 (95.5) |

| Professional Education* | ||

| Medical/Clinical (i.e., nurse, midwife, physician) | 21 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) |

| Counselling/Social Work/Psychology | 21 (50.0) | 14 (63.6) |

| Research | 9 (21.4) | 6 (27.3) |

| Other | 4 (9.5) | 2 (9.1) |

| Counselling Education | ||

| Master’s Degree | 1 (2.4) | 1 (4.5) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 16 (38.1) | 9 (40.9) |

| Certificate/Diploma | 19 (45.2) | 12 (54.5) |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 5 (11.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary Role at Clinic | ||

| Research Nurse | 20 (47.6) | 10 (45.5) |

| Counsellor | 20 (47.6) | 12 (54.5) |

| Other | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Responsibilities in HOPE apart from Options* | ||

| Clinical | 21 (50.0) | 10 (45.5) |

| Recruitment/participant tracking | 8 (19.0) | 5 (22.7) |

| Administrative | 11 (26.2) | 6 (27.3) |

| Staff training | 8 (19.0) | 4 (18.2) |

| HIV counselling | 30 (71.4) | 18 (81.8) |

| Other | 8 (19.0) | 5 (22.7) |

| Adherence counselling prior to HOPE | 38 (90.5) | 19 (86.4) |

| Adherence counselling in ASPIRE | 28 (66.7) | 15 (68.2) |

Participants could select more than one option

Among the 42-person analytic sample, 25% (n = 11) reported that many to most women found the general information about RDLs difficult to understand. Slightly more (n = 15, 35.7%) reported that many to most women found their own RDL results difficult to understand. This pattern was somewhat divergent for the 22-person interview sample. Twenty-seven percent (n = 6) reported that many to most women found both the general information about RDLs and their own results difficult to understand.

Residual Drug Level Themes

Table 2 documents themes and illustrative quotations for each RDL, summarized below.

Table 2.

Residual drug level themes from in-depth interviews (n = 22)

| RDL | Themes | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Navigating disappointment, denial and anger | OK, that was a challenging moment for the 0. You had [participant responses] in categories: there were those of 0 who would accept, “I didn’t use the ring.” Then there would be those at 0 and tell you, “I have never removed the ring. How come I have a 0?” So it was challenging. The easier ones were the other ones who would accept, “I have a 0. I didn’t use [the ring].” |

| The participants thought like we are judging them with the results. Because if you could tell them that you have got a 1 or a 0, they’re responding like, “Okay, do whatever you want to us.” So whenever you are continuing the counseling session, they were like, made a mood already like, “These people they have given me a 0, and whatever – the counseling that’s being done, it has nothing to do with me.” | ||

| An opportunity for candor | I also liked the way that she [participants in general] opened up. She would tell you the truth. And without even judging – I never even judged her to say, “Why are you not using the ring, and why have you changed?” She would easily open up to tell you what really was taking place. | |

| I used the tactic of not judging them but exploring, on what’s happened, if she forgot or whatever has happened to her for her not to use the ring but not judging her or pushing it. … With that strategy, some of the participants would just say, “Ah, maybe I might have forgotten what really happened to the ring,” something like that. | ||

| Turning toward prevention | I shouldn’t try and make the participant feel like she’s doing things wrong, because this is all about choice. So, in those cases what I’ll do is to always emphasize the fact that, you know, you still have the opportunity to change, if you don’t want to use the ring anymore. So, me at times if I would inform a participants that they are 0, I would also try to just reemphasize that, you know, it’s actually not too late for them to decide not to use the ring at all, in cases where they are finding it difficult to communicate that. | |

| If really they cannot take the disappointment of the 0’s, even if they are saying that they are using the Ring, you would give them other options, to say, “You can change if you would like to. We have other options. It’s not like the Ring is the only option,” so that they don’t feel like they are failures. | ||

| 1 | “In-between” is better, even if hard to define | There was a slight difference. When someone gets a 1, at least she knows there is some – a reasonable amount of the drug in her blood – but compare the 1 with a 0. The 0 itself – actually, it’s like, it passes a message that there is nothing, because it is a 0. It’s like, there is nothing in your system which reflects that you have been wearing the ring, compared with the 1, which shows that at least there is something, so the participant would have some hope. … [T]hese are just feelings from participants, but a 1 is better respected compared to a 0. |

| OK, there were moments where I’d feel helpless. I mean participants ask you “Why did I get a 1? I would use the ring all the time.” And then you wouldn’t really know – you’d be stuck, you didn’t know what exactly to say, and they would wonder, Is the ring really protecting me if I’m getting such low levels… | ||

| A 1 is easier to leverage into HIV prevention than a 0 | The women that got a 1, sometimes they don’t know where they … Because some of them will take 1 as a 0. “How I didn’t do well? I got a one!” And they will go on moaning and moaning and moaning, until you reassure them and say, but this 1 is showing that there was some level of protection. It’s not a 1 that is flying all over the place. It is showing that there was some level of protection. Now, let us look at your protection efforts. How can we improve your effort? And then you take it from there. | |

| They [who received a 1] understood it and admitted that it was possible that they could get a residual drug level of 1, and they promised to improve. Some of them for the following visits, they improved a lot. | ||

| Tiptoeing toward prevention | For example, if this participant says, “I’ve got a 1 and I’m not worried, because I was using the ring,” then there’s nothing much you can – you say. But if the participant says, “I’ve got a 1 and I’m worried,” then you could ask her, like, check in with her. “Were you using the ring? Did you have any challenges?” Or what or what. If the participant said, “I had challenges,” then we could discuss on the challenges and help her on the challenges she had mentioned. But if she said that, “I didn’t have challenges, and I have been using the ring consistently,” then we would just tell her to continue using the ring. If she had chosen to continue using the ring, that is. | |

| [I]n my mind maybe I thought that maybe she could have been lying to me that she’s been perfectly using the ring so we were going back to the Options Counseling without showing her that I’m doubting her. But we go through all the options again and let her make a final decision if she wants to change or to go to any other method or to add on the method that she’s choosing just so that she will be protected. | ||

| Some of them would then open to say, “Yeah, it’s because I remove the ring sometimes during bathing, I remove the ring sometimes during menses. Then this is why I am getting a 1.” They would then acknowledge the reason why they think they got a 1, though I couldn’t push on the reasons – they give me the reason – because it would be like judging them. | ||

| 2 | A 2 functioned almost like a 3 | The women who got a 2, most of them were fine with it. They were fine that – the 2’s and the 3’s, they didn’t really question the result. They felt protected. |

| [I]t was a bit of a challenge to competently explain why it’s in-between and not a three, because some participants got three rings and they would get a 3 in the first ring and they would get a 2 in the second one, and maybe another 2 in the third ring. So with the ring not being affected or taken out of her body, she would all at once inquire, “Why were the 2 results not a 3 as I used the ring the same way.” | ||

| Discrepancies between a 2 and 3 easily motivated HIV prevention | It showed their protection, but they felt that, “Wow, if I managed to make 2, what can stop me to make 3?” And then they get that courage to either to, “Wow, I can make it better than this. I can make it 100%.” So they get courage. | |

| But the bottom line was, the 3 is the highest protected level, so if we had a 3, we would be confident that you are protected from HIV. So with a 2, it’s like there is some encouragement to have 3 as a protection level. | ||

| 3 | Protection | Most of the participants [who received a 3] were very, very happy to – I should say all of them. They were happy to get a 3. And they didn’t ask any questions when they had a 3. |

| Oh, those would fly from your room to the waiting area … telling everyone, “I got a 3. I got a 3.” But now, imagine if people are singing, “I got a 3, I got a 3,” what if there’s a person that got a 0? And maybe the person that is trying to tell you that “I did everything that you said, but why am I getting a 0?” | ||

| Ambassadors to prevention | [W]e need not to forgot about them [who received 3’s] because they showed their commitment to the Ring. … Some of them, I requested them to become an ambassador to other women. They used to – they came forth and used to share their story with others to encourage them that this thing’s possible. So we had a very good relationship with those women. | |

| So we actually used the 3’s to talk to these 1’s, those who were getting the low level. | ||

| Prevention is not over | [T]hey were excited, and you’d actually feel proud of them, and you’d ask them how they feel, and they would tell you, “I’m excited.” But it became a challenge now dealing with those that end up seroconverting, and wondering how it did go wrong. And also, those who started off with 3, and then they may be having low residual drug levels now, the interaction, you’d tell that one is disappointed and one is wondering what is it, what has made her, you know move from a 3 to a 2 or a 1. | |

| But those are the people you actually, you don’t want them to go overboard being happy such that they forget about the bigger picture. Because the bigger picture is HIV prevention at the end. … [T]hey are happy, they are singing, they are doing everything – but at the end, it will also come back to HIV prevention. They will say, “I was using the ring as you instructed me. I was wearing it all the time. I never took it out. I think that’s why it worked for me.” |

0 RDL Conversations

Navigating disappointment, mistrust and anger.

When a woman “confessed” to not using the ring and this matched her 0 RDL, counselors generally reported no particular challenges. However, among women who maintained that they had used the ring consistently but to no avail, disappointment and mistrust were more common responses; this occasionally bordered on anger toward counselors. Some counselors anticipated an aversive counseling experience even before delivering a 0 RDL, anxiously wondering whether the participant might not accept their adherence feedback.

An opportunity for candor.

Even though a 0 RDL was difficult to give, many counselors reported that communicating 0’s in particular were an opportunity for women to consider how they used the ring and, when appropriate, to become more candid about not using it. At times, 0 RDLs functioned as a prompt to remember contextual factors that influenced women’s partial use or disuse of the ring. If counselors could respond neutrally when a participant’s self-reported adherence did not match her 0 RDL, counselors characterized this RDL feedback as an opportunity for candor among participants.

Turning toward prevention.

For some women, a 0 either motivated stronger adherence to the ring or consideration of alternatives to the ring. Counselors thought even if 0 RDLs disappointed or saddened participants or if a discrepancy between self-report and drug detection raised questions about the accuracy and veracity of the assay, ultimately RDL conversations did not discourage the use of the ring. Instead, 0 RDLs motivated conversations about prevention. Counselors also reported leveraging disappointment about low ring adherence to shift women to a different HIV prevention approach that did not rely so strongly on ring use.

1 RDL Conversations

“In-between” is better than a 0, even if hard to define.

Counselors barely distinguished between 0 and 1 RDL conversations, with slightly more favorable attitudes toward the higher rating as compared to the “failure” connoted by a 0. One counselor also considered 1 and 2 too similar to distinguish meaningfully, both being “in-between.” Another described difficulty responding to baffled participants who reported consistent ring use but whose RDLs somehow did not land on the clearer high end of 2 or 3.

A 1 is easier to leverage into HIV prevention than a 0.

Even with similarities between 0 and 1 RDL conversations, counselors reported greater ease leveraging the bit of protection connoted by a 1 into an exploration of a participant’s interest in improving her protection from HIV. Counselors found that a 1 offered a modicum of hope for not acquiring HIV and they specifically noted greater ease probing about problems women encountered while trying to use the ring. They also described how, at RDL 1, women more immediately offered contextual reasons for their low RDL, which could be solved or weighed against other more feasible options to prevent HIV that felt behaviorally congruent for that particular participant.

Tiptoeing toward prevention.

Even though a 1 was easier to leverage into HIV prevention than a 0, counselors expressed that a 1 marked just enough ring use that, for participants who were not already intrinsically concerned about HIV, there was little room to discuss improving HIV prevention – akin to a 0 RDL when a participant’s anger deterred further exploration. Those counselors who noted this problem sometimes abandoned further discussion of HIV prevention. Others relied on the same neutrality as they would with a 0. They broached the topic nonjudgmentally so as to communicate trust and encouragement, rather than focus too intently on pushing for a confession about the discrepancy, motivating gentle movement toward improved HIV prevention.

2 RDL Conversations

A 2 functioned almost like a 3.

Counselors recalled relative ease responding to participants who received a 2 RDL. At times, explaining fluctuations between a 3 and a subsequent 2 was challenging, but counselors characterized women receiving a 2 as comfortable and even happy with their level of HIV protection, particularly in contrast to the lack of protection indicated by a 0 or a 1.

Discrepancies between a 2 and 3 motivated HIV prevention.

Without the emotional barriers and mistrust that could arise during a 0 or a 1 RDL conversation, conversations about a 2 RDL very easily became opportunities to personalize objective feedback about HIV prevention. Even though the actual distinction between 2 and 3 was minimal, the numerical difference painted a vivid, quantified picture of the prevention potential available to women if they were to use the ring even more consistently. Counselors reported more easily transitioning women into a consideration of not just ring adherence but additional prevention options as well.

3 RDL Conversations

Protection.

The congruence between self-reported high adherence and a 3 RDL was particularly meaningful for women concerned about prevention. Counselors shared the joy and relief these participants expressed – and also noted that these participants did not ask difficult questions, like women typically did after receiving a lower RDL. One counselor worried about how women’s public exuberance about a high ‘score’ might affect other women who faced more disappointing news regarding their RDLs, a sole note of caution about the effects of drug monitoring data on the community of participants.

Ambassadors to prevention.

Some counselors relied on participants with consistent 3 RDLs to motivate women who received lower RDLs to consider how the ring might be a viable option. This could include functioning as an aspirational role-model but also providing practical problem-solving, like how to use the ring during menses.

Prevention is not over.

Some of the relief and joy counselors witnessed when women received a 3 RDL was difficult to navigate if those same women received diminishing RDLs over time. One counselor described a woman who seroconverted after receiving consistently high RDLs as a reminder to pursue prevention conversations even after communicating high RDLs. Overall, counselors considered a 3 RDL to be an important opportunity to discuss HIV prevention, though this seemed more of a priority for some counselors as compared to others.

Discussion

Findings show that discussing drug monitoring feedback is complex and requires careful navigation to minimize defensiveness, but may also be implemented in ways that motivate disclosure of non-adherence and evoke future aspirations to prevent HIV. A nonjudgmental stance, support for autonomy, and involvement of peers who could speak directly to women about their own ring use appeared to promote disclosure and problem-solving. Counselors reported that the majority of women in the trial understood both the concept of RDLs and their own individual RDL results specifically. Overall, counselors considered the framing of adherence levels as protection levels to be a useful opportunity to promote HIV prevention, if approached gently and in tune with women’s own motivations.

Numerical ratings were particularly meaningful both to women and to counselors, guiding their reactions and interventions. Counselors noted that adherence conversations might have been more cursory if based solely on self-report, without the anchoring metric of a woman’s current protection against HIV. However, at lower and higher RDLs, counselors recalled participant anger or elation that could interfere with pivoting toward HIV prevention. The natural variability of RDLs over time, a phenomenon that notably also occurs with biomarkers such as CD4 count [32-34], proved challenging. Although meaningful to participants, the actual distinctions between a 0 vs. 1 or a 2 vs. 3 were minimal and, at times, difficult to communicate. Still, counselors noted how feedback within each level of numerical RDL stimulated candor and more accurate reporting of partial and disuse of the ring. Counselors also balanced their descriptions of these challenges by referring to useful skills, like communicating neutrality and support for autonomy, in order to direct attention away from numerical results and toward women’s underlying motivations to prevent HIV, including to select alternatives to ring use.

The finding that drug monitoring feedback can promote disclosure and motivation toward HIV prevention is relevant both to treatment fidelity in clinical trials as well as treatment adherence in community-based settings where biological assays already routinely function as indicators of adherence. In another open label clinical trial, onetime drug detection monitoring was reportedly acceptable, with low levels prompting some participants to consider improving their adherence [11]. In other trials, however, participants responded to disclosure of pharmacokinetic results with surprise and disbelief, and more rarely with distress and sadness [10]. As a large clinical trial, MTN-025/HOPE is novel in that it incorporated feedback across study visits and our ancillary study is novel in that it evaluated counselor perspectives about how to conduct these conversations. Our findings also support the acceptability of drug monitoring feedback, but with a caveat: personalized feedback about objective measures appeared to be useful in the context of client-centered communication, which relied on feedback to counselors about their own fidelity to a client-centered approach [35]. Options Counseling specifically involved intentional navigation away from accusation and confrontation, toward supportive, nonjudgmental, and personalized problem solving. Receiving personalized feedback ratings themselves may have modeled the approach for counselors to use when communicating RDLs to participants.

Personalized feedback interventions, such as comparing population alcohol consumption norms to a particular individual’s own pattern [36], have an established and accepted history in helping people develop discrepancy and motivation [37], compelling consideration of changes that might otherwise remain mired in ambivalence [21,22]. Within HIV services, motivational interviewing, which originally included personalized feedback [23], has demonstrated efficacy in improving adherence [38]. Whether in clinical trials or service venues, personalized feedback interventions related to viral load, CD4 count, preexposure prophylaxis, or other biobehavioral interventions that rely on adherence may likewise afford an opportunity to fortify motivation, if administered in a client-centered fashion.

Across biomedical HIV prevention trials, participants have reported and insisted that they have used their assigned study products even when biomarkers indicated that they had not [1-5]. This was no exception in MTN-025/HOPE, as suggested by women who reported using the ring yet who received RDLs of 0. Reactions like anger or disavowal in response to a 0 RDL could have come from participants who mistakenly assumed that deliberately not using the ring would have jeopardized their continuation in the study and its perceived benefits. Indeed, participants from ASPIRE, the previous ring trial which fed into MTN-025/HOPE, did receive, value, and come to expect benefits like transport and food. Within our ancillary study among MTN-025/HOPE counselors, respondents reported that some former ASPIRE participants felt an expectation to choose the ring for their HIV prevention plan, in part because the previous trial had relied on their use of the ring. Despite the best of intentions and protocols to communicate the right to autonomy and the option to continue in the study even without ever using the ring, some women likely did not trust that counselors and the larger trial would indeed welcome choice. Although counselors did not describe participants feeling compelled to hide deliberate nonadherence in order to preserve perceived study benefits, assessments among participants themselves about RDL conversations would likely reveal greater insight into the discrepancies between self-report and objective measures, and the potential influence of study benefits on candor about actual product use.

Our study has limitations. Selection bias may influence our findings if those who did not participate differed from those who did, although session ratings among non-participants were comparable to those who did participate. We also relied on self-report, which may have introduced reporting bias. This was likely mitigated somewhat by ensuring that interviewers had had no prior contact with the counselors they each interviewed. In the future, access to recordings of sessions could further minimize reporting bias and add the benefit of mitigating recall bias by allowing direct observation. We should note that even with the potential for reporting and recall bias, counselors did voice meaningful difficulties that they and their participants experienced during RDL conversations. Another limitation derives from the parent study, an open-label trial in which women knew the HIV prevention benefits of using the vaginal ring. This limits the external validity of our findings with regard to biomedical trials that have yet to demonstrate efficacy. However, by the same token, this suggests relevance for other settings, such as clinics that monitor treatment through biomarker assays and that might therefore benefit from adherence conversations about drug monitoring.

Objective measures of adherence quantify protection in ways that can meaningfully guide discussions toward HIV prevention. This is to some extent mediated by an individual’s willingness to disclose actual adherence behaviors, a kind of candor that counseling in our study appeared to evoke. Communication at each level of adherence requires that counselors navigate emotional barriers, respond to questions about accuracy, and pivot conversation non-judgmentally and gently away from numerical results and toward the larger goal of HIV prevention. This is not an easy task. Both clinical trials and adherence counseling in the broader field of HIV prevention would likely benefit from further research to better understand how to personalize drug monitoring feedback effectively and optimally across contexts, to promote adherence to existing and future tools in the biobehavioral armamentarium.

Conclusion

An emphasis on women’s motivations to prevent HIV, rather than on the numerical value of residual drug monitoring, encouraged consistent users to continue using the ring and infrequent users to switch to an alternative HIV prevention approach. Findings suggest a role for drug detection monitoring feedback in future clinical trials as well as other clinical contexts where assays are already regularly performed, to motivate disclosure of actual adherence and commitment toward HIV prevention.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN), funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through individual grants (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615 and UM1AI106707) and supported by additional grants through the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH19139; P30MH43520), all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Informed consent

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Declarations of interest: None

Clinical Trial Number: NCT02858037

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, Taylor D, Ahmed K, Agot K, et al. FEM-PrEP: Adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. JAIDS. 2014;66:324–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu A, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, Amico RK, McMahan V, Mehrotra M, et al. Patterns and correlates of PrEP drug detection among MSM and transgender women in the global iPrEx study. JAIDS. 2014;67:528–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovirbased preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New Engl J Medicine. 2015;372:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. New Engl J Medicine. 2016;375:2121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Hartmann M, Minnis A. Methodological lessons from clinical trials and the future of microbicide research. Curr EHV-AIDS Rep. 2012;10:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amico RK, Marcus JL, McMahan V, Liu A, Koester KA, Goicochea P, et al. Study product adherence measurement in the iPrEx placebo-controlled trial: Concordance with drug detection. JAIDS. 2014;66:530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Straten A, Brown ER, Marrazzo JM, Chirenje MZ, Liu K, Gomez K, et al. Divergent adherence estimates with pharmacokinetic and behavioural measures in the MTN-003 (VOICE) study. JIAS. 2016;19:20642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker Z, Javanbakht M, Mierzwa S, Pavel C, Lally M, Zimet G, et al. Predictors of overreporting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in self-reported versus biomarker data. AIDS Behav. 2017;22:1174–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacQueen KM, Tolley EE, Owen DH, Amico RK, Morrow KM, Moench T, et al. An interdisciplinary framework for measuring and supporting adherence in HIV prevention trials of ARV-based vaginal rings. JIAS. 2014;17:19158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Straten A, Montgomery ET, Musara P, Etima J, Naidoo S, Laborde N, et al. Disclosure of pharmacokinetic drug results to understand nonadherence. AIDS. 2015;29:2161–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koester KA, Liu A, Eden C, Amico RK, McMahan V, Goicochea P, et al. Acceptability of drug detection monitoring among participants in an open-label pre-exposure prophylaxis study. AIDS Care. 2015;27:1199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne EN, Montgomery ET, Mansfield C, Boeri M, Mange B, Beksinska M, et al. Efficacy is Not Everything: Eliciting Women’s Preferences for a Vaginal HIV prevention product using a discrete-choice experiment. AIDS Behav. 2019;l–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corneli AL, McKenna K, Perry B, Ahmed K, Agot K, Malamatsho F, et al. The science of being a study participant: FEM-PrEP participants’ explanations for overreporting adherence to the study pills and for the whereabouts of unused pills. JAIDS. 2015;68:578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giguere R, Rael C, Sheinfil A, Balán IC, Brown W, Ho T, et al. Factors supporting and hindering adherence to rectal microbicide gel use with receptive anal intercourse in a phase 2 trial. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery ET, Mensch B, Musara P, Hartmann M, Woeber K, Etima J, et al. Misreporting of product adherence in the MTN-003/VOICE trial for HIV prevention in Africa: Participants’ explanations for dishonesty. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musara P, Montgomery ET, Mgodi NM, Woeber K, Akello CA, Hartmann M, et al. How presentation of drug detection results changed reports of product adherence in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:877–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balán IC, Giguere R, Brown W, Alex C-D, Horn S, Hendrix CW, et al. Brief participant-centered convergence interviews integrate self-reports, product returns, and pharmacokinetic results to improve adherence measurement in MTN-017. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:986–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy A, herer A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e185293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll KM, Farentinos C, Ball SA, Crits-Christoph P, Libby B, Morgenstern J, et al. MET meets the real world: Design issues and clinical strategies in the Clinical Trials Network. IS AT. 2002;23:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Benefield GR, Tonigan SJ. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. JCCP. 1993;61:455–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WR. Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual. DIANE Publishing; 1995;123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WR. Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment. DIANE Publishing; 1999;243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. JSAT. 2005;28:159–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amico RK, Miller J, Balthazar C, Serrano P, Brothers J, Zollweg S, et al. Integrated Next Step Counseling (iNSC) for sexual health and PrEP Use among young men who have sex with men: Implementation and observations from ATN110/113. AIDS Behav. 2018;11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amico RK, Mehrotra M, Avelino-Silva VI, McMahan V, Veloso VG, Anderson P, et al. Self-reported recent PrEP dosing and drug detection in an open label PrEP study. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1535–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amico RK, McMahan V, Goicochea P, Vargas L, Marcus JL, Grant RM, et al. Supporting study product use and accuracy in self-report in the iPrEx study: next step counseling and neutral assessment. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1243–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moyers TB. The relationship in motivational interviewing. Psychotherapy. 2014;51:358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New Engl J Medicine. 2010;363:2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balan IC, Giguere R, Lentz C, Kutner BA, Kajura-Manyindo C, Byogero R, Asiimwe FB, Makala Y, Jamaya J, Khanyile N, Chetty D, Soto-Torres L, Mayo A, Mgodi NM, Palanee-Phillips T & Baeten J. Client-centered adherence counseling with adherence measurement feedback to support use of the dapivirine ring in MTN-025 (The HOPE Study). (Under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh. 2017.

- 31.NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 2019.

- 32.Spence P, Nel A, van Niekerk N, Derrick T, Wilder S, Devlin B. Post-use assay of vaginal rings (VRs) as a potential measure of clinical trial adherence. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2016;125:94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raboud J, Haley L, Montaner J, Murphy C, Januszewska M, Schechter M. Quantification of the variation due to laboratory and physiologic sources in CD4 lymphocyte counts of clinically stable HIV-infected individuals. JAIDS. 1995;10 Suppl 2:S67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venter W, Chersich MF, Majam M, Akpomiemie G, Arulappan N, Moorhouse M, et al. CD4 cell count variability with repeat testing in South Africa: Should reporting include both absolute counts and ranges of plausible values? Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29:1048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giguere R, Lentz C, Kajura-Manyindo C, Kutner BA, Dolezal C, Buthelezi M, Lukas I, Nampiira S, Rushwaya C, Sitima E, Katz A, van der Straten A & Balán IC. Building client-centered counseling skills for an HIV-prevention study in Africa. (Under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Dimeff L, Baer J, Kivlahan D, Marlatt G Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS). Guilford Press: New York: 1999;200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riper H, van Straten A, Keuken M, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Curbing problem drinking with personalized-feedback interventions: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dillard PK, Zuniga J, Holstad MM. An integrative review of the efficacy of motivational interviewing in HIV management. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]