Abstract

Background:

Developmental context is related to the propensity to engage in alcohol use, the rate at which alcohol use changes, and the relevance of different risk factors to alcohol use disorder (AUD). Therefore, studies of change should consider developmental nuances, but change is often modeled to follow a uniform pattern, even across distinct developmental periods.

Methods:

This study implemented a novel analytic approach to delineate developmental periods of alcohol behavior (n=478, ages 18-35). This approach was further leveraged to examine age-related shifts in the association of impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, alcohol enhancement expectancies) with alcohol behavior (alcohol quantity*frequency, heavy drinking, AUD).

Results:

A sequence of exploratory and confirmatory latent growth models (LGMs) suggested modeling separate linear change factors for alcohol behavior during the primary college (ages 18-21) and post-college years (21-35). Bivariate LGMs estimated correlations for alcohol behavior changes with lack of planning, sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies during these periods. The rate at which heavy drinking changed during the college years was positively correlated with general sensation seeking and lack of planning during this period (rs=.61–.63). These correlations were significantly weaker during the post-college years (rs=.29–.34). Notably, the rate of change in alcohol behavior was strongly correlated with enhancement expectancies during the college (r=.45–.70) and post-college years (r=.45–.61).

Conclusions:

These findings highlight the importance of sensation seeking and lack of planning with regard to adult alcohol use, particularly in a college environment. There was also a strong link between the rates of change in alcohol behavior and enhancement expectancies across all waves.

This study supports the utility of exploratory LGMs for delineating developmental periods of alcohol behavior, which are characterized by different processes.

Keywords: change, latent growth models, exploratory, alcohol, impulsivity, sensation seeking

Change is often examined as a single event that follows a uniform pattern (e.g., linear change across a given timeframe), but changes more likely fluctuate across developmental periods. For example, drinking patterns may be affected by subtle changes, such as maturation/aging and increasing responsibilities, as well as by stark changes, such as role transitions and moving in/out of environmental contexts (Dawson et al., 2006, Lee et al., 2015, Quinn and Fromme, 2011). As a result, normative and problematic alcohol use may increase/decrease, and the rates of those changes may shift based on a person’s developmental context (Deboeck et al., 2015). For similar reasons, risk factors likely vary in importance across the lifespan, such as familial and peer influences (Boyd et al., 2014). Thus, rather than assuming uniform change across many years, it is critical to consider the nuances of development when modeling change and assessing the correlates of alcohol behavior. Here, we apply a novel, data-driven analytic approach to identify developmental periods of alcohol use in adulthood (ages 18–35) and examine the relevance of impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, alcohol enhancement expectancies) to alcohol use during these periods.

Emerging adulthood comprises the most substantial fluctuations in alcohol use of any developmental period (Sher and Gotham, 1999). Steep increases in alcohol use and problems are frequent in emerging adulthood, particularly among college attendees (Slutske, 2005), followed by a “maturing out” of problematic use as occupational and familial obligations take priority (Lee et al., 2015, Littlefield et al., 2010, Winick, 1962). It is possible that certain developmental contexts, such as college, provide ample opportunity to drinking. As a result, the college environment may lead to elevated drinking, particularly for those who are prone to risk-taking and heavy alcohol use (e.g., high in sensation seeking, low in impulse control). Therefore, risk factors may vary in their importance to alcohol use and problems across the developmental contexts of adulthood. Understanding how individual differences underlie alcohol behavior changes during emerging and young adulthood may help identify relevant targets of interventions during these distinct developmental periods.

Individual differences in the impulsivity facets sensation seeking and lack of planning are associated with problematic alcohol use (Casey et al., 2008, Stacy and Wiers, 2010, Wiers and Stacy, 2006). Further, distinct trajectories have been observed for sensation seeking and impulse control (similar to lack of planning) via self-report, behavioral, and neuroimaging assessments (Casey et al., 2010, Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011, Steinberg, 2010). Whereas sensation seeking increases rapidly during adolescence until around age 15–17 (Littlefield et al., 2016, Pedersen et al., 2012, Romer and Hennessy, 2007, Steinberg et al., 2008), impulse control increases gradually from adolescence through emerging adulthood (Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011). These developmental patterns may underlie shifts in risk-taking and alcohol behavior that occur in emerging adulthood.

Although impulse control and sensation seeking follow distinct developmental trajectories, their curvilinear change is moderately correlated (r=.41; Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011). Specifically, sensation seeking continues to change after adolescence, albeit at a slower rate, while impulse control plateaus after emerging adulthood. Additionally, the correlated linear change among these constructs may be conditional on how quadratic change is modeled (for modeling considerations, see King et al., 2017, Littlefield et al., 2014). Thus, understanding how changes in impulsivity facets are related to each other and other constructs likely depends on how change is modeled. For example, models of change may be best fit within distinct developmental periods, such as before/after periods of pronounced change, rather than as trajectories that span distinct developmental periods.

Impulsivity facets are also related to alcohol behavior changes. A prior study of the current sample found that linear changes in alcohol use, from ages 18 to 35, are correlated with linear changes in disinhibition (i.e., lack of impulse control, r=.42; Littlefield et al., 2009). Similarly, findings from a nationally-representative sample, spanning ages 15–26, suggested that linear changes in alcohol use are correlated with changes in impulsivity (r=.28) and sensation seeking (r=.15; Quinn and Harden, 2013). However, examining these relations in more narrowly defined periods may provide a more fine-grained understanding of how impulsivity facets relate to alcohol behavior across the lifespan (Grimm and Ram, 2018).

To characterize the developmental patterns of alcohol behavior and identify relevant risk factors across adulthood, data-driven analytic approaches may be preferable to purely theoretical approaches that assume, a priori, patterns of change. To accomplish this, Grimm and colleagues (2013) proposed an exploratory growth modeling approach to assess the pattern of freely estimated loadings across multiple assessments for a given construct, instead of constraining factor loadings to indicate a specific pattern of change. Loadings may, for example, indicate a linear change, quadratic change, or piecewise change process. Based on the change process(es) identified in an optimally fitting exploratory model, confirmatory models can fit those change process(es) and examine how they relate to different risk factors. For example, alcohol behavior may change at different rates over time, depending on the developmental period, and risk factors may vary in their relevance over time as well.

In addition to considering how to model change, it is worth examining how constructs are assessed with regard to a given behavior. In particular, it may be useful to assess constructs, such as facets of impulsivity, specific to a given behavior, such as alcohol behavior. For example, sensation seeking, broadly, is defined as the tendency to seek “varied, novel, complex, and intense” experiences (Zuckerman, 1994, p. 27). Alcohol enhancement expectancies are a conceptually related construct and indicate individual differences in the rewards that one expects from drinking (e.g., increased enjoyment, excitement, sociability) (Sher, 1985, Thush et al., 2008). That is, sensation seeking indicates the tendency to pursue rewarding experiences, and alcohol enhancement expectancies indicate the degree to which a person anticipates that drinking, specifically, will be rewarding. Despite sensation seeking and enhancement expectancies being conceptually similar, they are only weakly correlated in prior studies, which may suggest that they are distinct risk constructs (r=.22–.23 for enhancement expectancies with Zuckerman Sensation Seeking subscales; Finn et al., 2000). Thus, it may be beneficial to assess how general measures of impulsivity, such as sensation seeking, and alcohol-specific measures of impulsivity, such as enhancement expectancies, relate to alcohol behavior cross-sectionally and across developmental contexts.

The current study examined the relation between alcohol behavior changes (alcohol use, heavy drinking, AUD) and impulsivity facets (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, alcohol enhancement expectancies). These risk factors were assessed seven times, from ages 18–35, to examine how they relate to normative and problematic use during the formative years of alcohol behavior. Four assessments were administered annually during the college years (ages 18-21) and three assessments during early adulthood (ages 25–35). First, exploratory latent growth models (LGMs) were applied to identify the best-fitting change structure of each construct, such as linear/quadratic or piecewise change. Informed by exploratory models, confirmatory models estimated correlated changes between alcohol measures (use and AUD symptoms) and risk factors (lack of planning, sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies). We hypothesized that the slopes (i.e., rate of change) of alcohol behavior would be positively correlated with the slopes of lack of planning, sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies. Further, we hypothesized that these correlations would be most pronounced during emerging adulthood, when alcohol behavior is rapidly changing and reaches its peak for many individuals.

Method

Participants

Participants were 489 first-year college students (Caucasian=93%; female=52%; M age=18.2) who were enrolled in the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior Study (AHB) and followed for six additional waves (ages 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, 35). All data were collected when the legal drinking age was 21. At the last wave, 78% of the initial sample had been retained. Participants who abstained from alcohol use across all seven waves (n=6) and those who had missing data on all self-report measures were excluded from analyses (n=5), resulting in 478 participants. Participants with a family history of alcohol use disorder (AUD) were overrecruited (51%; see below). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Missouri approved the study procedures (protocol 02-02-090, “Long-Term Consequences of Collegiate Alcohol Involvement”).

Measures

Family History of AUD.

Family history of AUD was based on responses to adaptations of the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test for paternal and maternal drinking problems (Crews and Sher, 1992) and the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria interview (Endicott et al., 1978). Criteria for an AUD family history were: 1) paternal drinking problems were scored four or higher on the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, and 2) Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria for alcoholism (Sher et al., 1991). Participants were considered to have no AUD family history if: 1) no first-degree relative received a diagnosis of an AUD or antisocial personality disorder; and 2) there was no AUD or other substance use disorder in a second-degree relative. Sex and AUD family history were modeled as exogenous variables in all bivariate LGMs to control their potential influence on alcohol behavior and personality.

Alcohol Behavior.

Alcohol behavior was measured by normative use (quantity and frequency) and heavy drinking (i.e., intoxication and binge drinking frequency). Normative use was measured using alcohol quantity-frequency (QF; Jackson and Sher, 2006), the typical quantity (average drinks per drinking occasion) multiplied by the frequency of drinking (per week). Heavy drinking was measured by a composite comprised of the frequencies of getting “a little high or light-headed on alcohol,” “drunk (not just a little high),” and binge drinking (“5 or more drinks”) in the previous 30 days. Items comprising the heavy drinking composite have demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the AHB (α = .80 - .90; Piasecki et al., 2005, α=.91; Sher et al., 1991).

The AUD section of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule provided a past-year AUD symptom count (DIS-IIIA, Robins et al., 1985). The DIS is a semi-structured interview for psychiatric diagnostic information. At Wave 1, the DIS was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III; American Psychiatric, 1980). In subsequent waves, newer versions of the DIS were employed as they became available for the DSM-III-R (Robins et al., 1989) and DSM-IV (Robins et al., 1995). To maintain compatibility in how AUD was operationalized and diagnosed across waves, earlier DIS questions were included with the updated DIS version in later waves.

All alcohol variables were non-normally distributed (alcohol QF: skewness=10.4, kurtosis=148.5; heavy drinking: skewness=4.0, kurtosis=18.5; AUD: skewness =3.0 , kurtosis=11.5). These variables were binned and analyzed with a threshold model, which has been shown to yield unbiased estimates when applied to non-normally distributed data (Derks et al., 2004). For AUD, binning was based on DSM5 symptom cutoffs to indicate absent (0-1 endorsed symptoms; Wave 1=45.2%, Wave 7=86.4%), mild AUD (2-3 symptoms; Wave 1=34.7%, Wave 7=9.8%), moderate AUD (4-5 symptoms; Wave 1=15.3%, Wave 7=2.5%), and severe AUD (6+ symptoms; Wave 1=4.8%, Wave 7=1.4%). For consistency, alcohol QF and heavy drinking were also binned into four categories. Thresholds for these categories were chosen to approximate the percentiles observed for categories of AUD. For alcohol QF, categories were: 0-6 drinks per week (Wave 1=60.3%, Wave 7=82.0%); 7-13 drinks per week (Wave 1=21.6%, Wave 7=10.4%); 14-27 drinks per week (Wave 1=13.4%, Wave 7=6.5%); and 28+ drinks per week (Wave 1=4.6%, Wave 7=1.1%). For the heavy drinking composite, categories of heavy drinking frequency in the previous 30 days were: no more than once (Wave 1=35.1%, Wave 7=71.9%); less than weekly (Wave 1=44.3%, Wave 7=22.3%); up to three times per week (Wave 1=17.4%, Wave 7=4.4%); more than three times per week (Wave 1=3.2%, Wave 7=1.4%).

Risk Factors.

The Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1975), Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1968), and selected scales from the Minnesota Multiphasic Inventory-II (Hathaway and McKinley, 1943) were administered at all seven waves to assess lack of planning and sensation seeking (Sher et al., 1991). These measures consisted of dichotomous (true-false, yes/no) questions regarding individual tendencies. Mean responses across items were used in analyses, indicating a endorsement rate for lack of planning and sensation seeking.

Four items assessed lack of planning: 1) “I do and say things without stopping to think;” 2) “I often do things on the spur of the moment;” 3) “I think things over before doing anything;” 4) and “I am usually carefree.” These items are from a 10-item measure previously analyzed from Waves 1, 5, 6, and 7 of this sample (Littlefield et al., 2009). These four items were chosen because they were administered at all seven waves (all 10 items were only assessed at Waves 1, 5-7). Given the scaling of these items, this measure indicated a lack of planning. That is, higher scores indicate less impulse control and greater impulsivity.

Sensation seeking was assessed with measures of general sensation seeking (general sensation seeking [SS]) and alcohol-reward seeking (alcohol expectancies). Four items assessed general sensation seeking: 1) “I often long for excitement;” 2) “At times I have a strong urge to do harmful, shocking things;” 3) “(I) would do almost anything for a dare;” and 4) “I have never done anything dangerous for the thrill of it (reverse scored).”

At each wave, nine items assessed alcohol enhancement expectancies to measure alcohol-specific sensation seeking (Sher et al., 1996, Kushner et al., 1994). Participants were asked to choose “how much (they) expect” various effects from drinking on a five-point Likert-type scale (0=“Not at all,” 4=“A lot”). Representative enhancement expectancy items include “Drinking makes many activities more enjoyable,” “Drinking makes celebrations more enjoyable,” and “Drinking can be exciting” (see supplemental material for all items). A mean score for responses on the nine enhancement expectancy items was computed, resulting in a 0-4 score (0=responding “Not at all” to all items”, 4=“A lot” to all items).

Analytic Procedures

LGMs were conducted to examine the nature of change and co-development of alcohol behavior (alcohol QF, heavy drinking, AUD) and impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, enhancement expectancies) (Meredith and Tisak, 1990). Additionally, these models examined whether changes in risk factors are correlated with alcohol behavior. Analyses were conducted in three steps: 1) exploratory LGMs informed the number of growth factors to fit; 2) confirmatory LGMs identified the best-fitting growth structure for each measure; and 3) bivariate LGMs estimated the correlations between the intercept and slope (i.e., rate of change) factors for impulsivity risk factors and alcohol behavior. All analyses were conducted in Mplus, and model scripts were produced using the MplusAutomation package in R (Hallquist and Wiley, 2018, Muthén and Muthén, 1998). Missing data were handled using full-information maximum likelihood, which is preferable to other methods (e.g., listwise deletion) even when certain assumptions are not met (e.g., data missing at random; see Graham, 2009).

Exploratory LGMs.

We used a two-step approach to measure the change in impulsivity risk factors and alcohol behavior, from ages 18–35 (Grimm et al., 2013). First, a sequence of exploratory models was conducted to determine the number of growth factors that best fit change for each measure: 1) a tau-equivalent, random intercept model (all loadings fixed to one); 2) a 1-factor model (all loadings freely estimated); 3) an intercept + 1-factor model (one factor with all loadings fixed to one, one factor with all loadings freely estimated); 4) a 2-factor model (two factors with loadings freely estimated); and 5) an intercept + 2-factor model (one factor with all loadings fixed to one, two factors with all loadings freely estimated). Modeling a freely estimated factor indicates an unconstrained pattern of change across assessments. Modeling a random intercept indicates individual differences in the modeled variable across assessments (e.g., the tendency for low/high alcohol use). When including an intercept with a freely estimated factor, the freely estimated factor loadings indicate change relative to the intercept. Within a confirmatory model (below), growth factor loadings indicate individual differences in change relative to a reference point. For example, the measured variable at the first assessment is most often the reference point, and the growth factor loadings indicate change relative to the first assessment.

All exploratory latent growth factor correlations were fixed to zero to aid model convergence and secure a mathematically identified solution. Further, no specific functional form was imposed on the non-intercept factors, and loadings were freely estimated using the “(*1)” specification in Mplus to indicate that exploratory factors are being estimated. This allowed the loading patterns to inform how to model change in confirmatory LGMs. This approach has been described as “right-sizing” models to longitudinal data, instead of assuming change follows a predetermined pattern (Wood et al., 2015).

Confirmatory LGMs.

After a factor structure was chosen, model fit was compared to determine whether change was best measured by concurrent growth processes (e.g., linear and quadratic change) or separate growth processes (e.g., piecewise change). Correlations among the slopes were fixed to zero.

Bivariate LGMs.

The degree to which the rates of change in alcohol behavior were correlated with the rates of change in lack of planning, general sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies were examined within the growth curve structure identified in exploratory and confirmatory LGMs. Residual variances were freely estimated and uncorrelated across waves. These analyses aimed to build on previous findings of correlated changes between lack of planning and alcohol behavior in adults (Littlefield et al., 2009) and sensation seeking and lack of planning through emerging adulthood (Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of all measures at the most recent wave of. data collection. Measures of alcohol behavior were strongly correlated with each other at the most recent wave (r=.67–.85). Adequate internal consistency was observed across all waves for the items assessing lack of planning (ω=.74–.84), sensation seeking, (ω=.69–.81), and alcohol expectancies (ω=.84–.88). Cross-sectional correlations were weak between alcohol behavior and lack of planning (r=.12–.15) and general sensation seeking (r=.14–.29), but correlations were moderate for alcohol behavior and enhancement expectancies (r=.49–.50). Notably, cross-sectional correlations tended to be stronger at prior waves for alcohol behavior with lack of planning (r=.11–.33) and sensation seeking (r=.15–.30) but not enhancement expectancies (r=.34–.57). Lack of planning and general sensation seeking were weakly correlated across all waves (.16–.23), consistent with the literature (.23-.27; Ellingson et al., 2013, Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011, Smith et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of measures at the most recent wave of data collection (age 35).

| Alcohol QF | Heavy Drinking a | AUD Symptoms b | Lack of Planning | General Sensation Seeking | Enhancement Expectancies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol QF | 1 | |||||

| Heavy Drinking a | .85 (.03) | 1 | ||||

| AUD Symptoms b | .67 (.06) | .70 (.05) | 1 | |||

| Lack of Planning | .12 (.06) | .15 (.06) | .16 (.07) | 1 | ||

| General Sensation Seeking | .14 (.06) | .22 (.05) | .29 (.07) | .17 (.05) | 1 | |

| Enhancement Expectancies | .50 (.06) | .50 (.05) | .49 (.06) | .13 (.05) | .23 (.05) | 1 |

| Mean (SD) | NA | NA | NA | 0.32 (0.28) | 0.15 (0.21) | 1.07 (0.64) |

| Skewness | NA | NA | NA | 0.69 | 1.40 | 0.58 |

| Kurtosis | NA | NA | NA | −0.30 | 1.46 | −0.10 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. Means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis statistics for continuous variables are presented below correlation estimates. All alcohol measures were binned into ordinal, polytomous variables comprised of four categories.

Heavy drinking was computed as the mean number of days high, drunk, and binge drinking in the previous 30 days.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) symptoms was based on DSM-IV alcohol dependence (bins were chosen to match DSM5 levels of AUD severity). Correlations are presented for Wave 7.

Given that items from different scales were used to comprise the risk factors (lack of planning, sensation seeking), measurement invariance across waves was assessed to examine whether measurement changes over time might be due to age-related changes in the measurement of the risk factors. For each impulsivity risk factor, chi-square difference tests were conducted (using the Mplus DIFFTEST option) between models with freely estimated variance/covariance matrices across waves and fixed variance/covariance matrices across waves. In these models, the variance/covariance matrices were not significantly different across waves for lack of planning (χΔ [dfΔ=56]=45.89, p=.83), general sensation seeking (χΔ [dfΔ=56]=26.29, p=.99), or alcohol enhancement expectancies (χΔ [dfΔ=261]=298.07, p=.06). Thus, the change assessed in subsequent models does not appear to be due to age-related differences in the measurement of these measures.

Exploratory LGMs

Exploratory LGMs were conducted to inform the growth factor structure of all risk factors and alcohol measures (ages 18–35). Specifically, the following five models were fit: 1) tau-equivalent (intercept only – all loadings fixed to one); 2) 1-factor (loadings freely estimated); 3) intercept + 1-factor (one factor with all loadings fixed to one, one factor with all loadings freely estimated); 4) 2-factor (two factors with all loadings freely estimated); 5) 2-factor + intercept (one factor with all loadings fixed to one, two factors with all loadings freely estimated). The best-fitting model was chosen based on the CFI and RMSEA fit statistics (see supplemental Table S1). To assess RMSEA, the probability that the estimate was less than .05 was consulted, rather than the point estimate of the RMSEA, because some RMSEA estimates were equivalent (e.g., <.001 for several models). A piecewise latent growth model (i.e., 2-factor+intercept) best fit the data for all measures across ages 18–35. For all alcohol variables, one factor comprised loadings that increased across the college years and decreased across the post-college years (see supplemental Table S2). The second factor comprised loadings that followed a linear pattern across all waves.

Emphasis was given to models that best explained changes in alcohol measures. As a note, it is not necessary for constructs to be modeled using the same growth structure (e.g., alcohol use and risk factors); however, most impulsivity risk factors had similar loading patterns as alcohol behavior, and taking this approach can simplify finding and aide interpretability. Models were ultimately chosen after inspecting loadings, as well as estimated and observed means, with emphasis was given to interpretability (see supplemental Figure S1). It was concluded that the factor loadings and mean trajectories suggested modeling one factor that assessed change during the college years and a second factor that assessed change during the post-college years.

Confirmatory LGMs

Confirmatory LGMs were conducted, with orthogonal linear growth factors for Waves 1-4 and Waves 4-7. Figure S1 displays the estimated and observed means for all variables and demonstrates the adequacy of model fit. Further, growth factor variances were significant for all variables (see Table S3 for fit and variance estimates). Thus, confirmatory models provided adequate fit across all measures (CFIs>.95, RMSEAs<.08 [90% CIs=.000, .071]; Browne and Cudeck, 1993, Carlson and Mulaik, 1993).

Estimated and observed means were evaluated to identify trajectories across measures. Lack of planning and general sensation seeking decreased rapidly from Waves 1-4 and then gradually decreased from Waves 4-7. Enhancement expectancies decreased from Waves 1-4 and then gradually increased from Waves 4-7. For alcohol behavior, alcohol QF and heavy drinking increased from Waves 1-4 and then steeply decreased from Waves 4-7, whereas AUD decreased across all Waves.

Bivariate LGMs

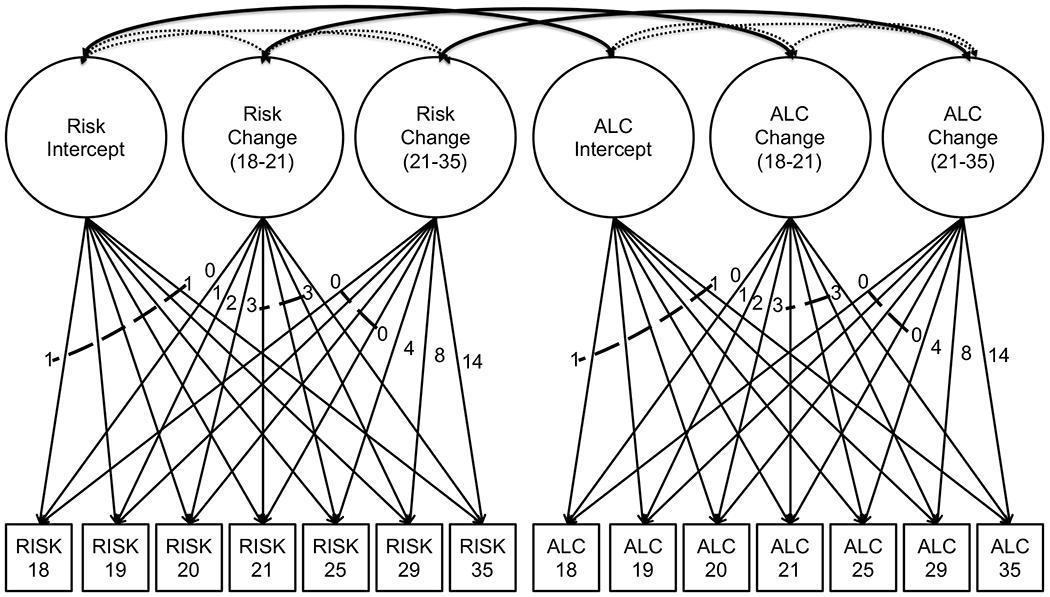

Bivariate LGMs estimated the correlations between the intercept (age 18) and piecewise growth factors (ages 18-21, 21-35) for alcohol behaviors (alcohol QF, heavy drinking, AUD) and each risk factor (lack of planning, sensation seeking, enhancement expectancies) (see Figure 1). Across all models, the intercept factor loadings were fixed to 1 for Waves 1-7. Wave 1 was the reference point for modeling the change factors, on which all loadings from both change factors were fixed to 0. All other Waves were modeled with reference to Wave 1 (i.e., age 18), so that loadings across both change factors on Wave 2 summed to 1 (age 19; 1+0=1); Wave 3 fixed loadings summed to 2 (age 20; 2+0=2); Wave 4 loadings summed to 3 (age 21; 3+0=3); Wave 5 loadings summed to 7 (age 25; 3+4=7); Wave 6 loadings summed to 11 (age 29; 3+8=11); and Wave 7 loadings summed to 17 (age 35; 3+14=17). Thus, the primary-college change factor loaded only on Waves 1-4 (i.e., assessing the rate of change from ages 18-21), with equivalent loadings on Waves 4-7 loadings to account for the prior influence on change from ages 21-35. The post-college change factor loaded on Waves 4-7 (i.e., assessing the rate of change from ages 21-35), with loadings on Waves 1-4 fixed to zero.

Figure 1.

Bivariate latent growth models, estimating factors for the intercept, change at Waves 1-4 (ages 18–21), and change at Waves 4-7 (age 21–35) alcohol behavior (alcohol QF, heavy drinking, alcohol use disorder) and risk factors (lack of planning, sensation seeking, enhancement expectancies).

RISK=impulsivity risk factors (modeled as lack of planning, general sensation seeking, enhancement alcohol expectancies in separate models). ALC=alcohol behavior (modeled as alcohol quantity*frequency, heavy drinking, and alcohol use disorder in separate models). All alcohol behavior measures were modeled as ordered, polytomous variables. The parameters of greatest interest were the correlations between intercept and change factors of alcohol behavior and risk factors, depicted by solid, bold slings. All intercept and change factors were allowed to correlate in the model, but only those between sensation seeking and lack of planning (dashed slings), and within each construct (dotted slings) are depicted in the figure. Dashed lines across loadings indicate the same loading applied to all intermediate paths (e.g., all intercept loadings are 1; the Waves 4-7 loadings on the Wave 1-4 change factor are all 3). In addition, family history and gender were included as covariates for each factor.

The fit across bivariate LGMs was adequate (CFIs=.987–1.00, RMSEAs=.001–.029). Table 2 displays the correlated intercept and change factors among lack of planning, sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies. There were moderate correlations between lack of planning and general sensation seeking for the intercepts (r=.37) as well as the growth factors capturing variance in the rate of change from Waves 1-4 (r=.46), consistent with prior studies. For Waves 4-7, however, correlated changes in lack of planning and general sensation seeking were statistically nonsignificant (r=.19). Lack of planning and enhancement expectancies were correlated for the intercept (r=.25) and changes during Waves 4-7 (r=.24) but not changes during Waves 1-4 (r=.12). Table 3 displays the correlation estimates among the intercept and change factors (i.e., rates of change) for impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, alcohol enhancement expectancies) and alcohol behavior. The results displayed in Table 3 are discussed below.

Table 2.

Correlations among latent growth factors for lack of planning, general sensation seeking, and enhancement expectancies.

| Lack of Planning |

General Sensation Seeking |

Enhancement Expectancies |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Curve Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Lack of Planning | |||||||||

| 1) Intercept | |||||||||

| 2) Slope 1 (18-21) | −.38 (.08)*** | ||||||||

| 3) Slope 2 (21-35) | −.31 (.10)** | −.16 (.13) | |||||||

| General Sensation Seeking | |||||||||

| 4) Intercept | .37 (.07)*** | −.14 (.10) | −.09 (.10) | ||||||

| 5) Slope 1 (18-21) | −.39 (.13)** | .46 (.17)** | −.11 (.15) | −.41 (.10)*** | |||||

| 6) Slope 2 (21-35) | .04 (.09) | −.08 (.12) | .19 (.11) | −.50 (.11)*** | −.08 (.17) | ||||

| Enhancement Expectancies | |||||||||

| 7) Intercept | .25 (.06)*** | −.11 (.08) | −.12 (.08) | .42 (.06)*** | −.24 (.11)* | −.16 (.08)* | |||

| 8) Slope 1 (18-21) | −.18 (.08)* | .12 (.11) | .12 (.11) | −.35 (.09)*** | .45 (.16)** | .04 (.11) | −.64 (.05)*** | ||

| 9) Slope 2 (21-35) | −.03 (.07) | −.10 (.10) | .24 (.09)** | −.06 (.08) | −.11 (.13) | .32 (.09)*** | −.17 (.07)* | .02 (.10) | |

| Means | 0.511 | −0.031 | −0.007 | 0.379 | −0.044 | −0.010 | 1.173 | −0.053 | 0.012 |

| Residual Variance | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.446 | 0.020 | 0.001 |

Note: Standard errors are provided in parentheses.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05. Means and residual variances are from standardized models. All mean and residual variance estimates were significant at p < .01.

Table 3.

Correlation estimates and standard errors for the intercept and slope parameters from bivariate latent growth models of alcohol behavior (alcohol QF, heavy drinking, AUD Symptoms) and impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, alcohol enhancement expectancies).

| Alcohol Behavior | Lack of Planning | General Sensation Seeking | Enhancement Expectancies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Correlations | |||

| Alcohol QF | .46 (.06)*** | .29 (.07)*** | .61 (.04)*** |

| Heavy Drinking | .43 (.06)*** | .29 (.07)*** | .71 (.03)*** |

| AUD Symptoms | .39 (.06)*** | .41 (.07)*** | .61 (.05)*** |

| Slope Correlations (Waves 1-4) | |||

| Alcohol QF | .27 (.14) | .31 (.17) | .48 (.11)*** |

| Heavy Drinking | .63 (.18)*** | .61 (.21)** | .70 (.12)*** |

| AUD Symptoms | .23 (.15) | .48 (.18)** | .45 (.12)*** |

| Slope Correlations (Waves 4-7) | |||

| Alcohol QF | .21 (.13) | .11 (.14) | .45 (.12)*** |

| Heavy Drinking | .34 (.14)* | .29 (.12)* | .51 (.10)*** |

| AUD Symptoms | .16 (.14) | .46 (.14)** | .61 (.12)*** |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05. One set of models included lack of planning and general sensation seeking. Another set of models included lack of planning and enhancement expectancies (as a measure of alcohol-specific sensation seeking).

Alcohol Behavior and Lack of Planning.

The intercepts of all alcohol measures were correlated with lack of planning (rs=.39–.46). At Waves 1-4, changes in lack of planning were moderately correlated with changes in heavy drinking (r=.63), but correlations were not significant for alcohol QF (r=.27, p=.057) and AUD symptoms (r=.23, p=.12). Similarly, at Waves 4-7, changes in lack of planning were correlated with changes in heavy drinking (r=.34), but not alcohol QF (r=.21, p=.11) or AUD symptoms (r=.16, p=.25). Given the discrepancy between the correlated change for lack of planning and heavy drinking during Waves 1-4 and Waves 4-7, a subsequent model constrained these estimates. Chi-square difference tests suggested that changes in lack of planning were more strongly associated with changes in heavy drinking in the college years (.63) than during the post-college years (.36) (χΔ [dfΔ=1]=12.56, p<.001). In summary, changes in lack of planning were associated with heavy drinking during both periods, but associations were significantly stronger during the college years.

Alcohol Behavior and Sensation Seeking.

The intercepts of all alcohol measures were correlated with general sensation seeking (rs=.29–.41). Changes in general sensation seeking were correlated with changes in AUD symptoms during both Waves 1-4 (r=.48) and Waves 4-7 (r=.46). In addition, general sensation seeking changes were associated with heavy drinking changes at Waves 1-4 (rs=.61) and Waves 4-7 (r=.46). Changes in sensation seeking were not significantly associated with changes in alcohol QF during either timeframe. Again, given the discrepancy between the correlated change for sensation seeking and heavy drinking during Waves 1-4 and Waves 4-7, a subsequent model constrained these estimates. Constraining these parameters suggested that sensation seeking changes were more strongly associated with heavy drinking changes in the college years (.61) than during the post-college years (.29) (χΔ [dfΔ=1]=9.42, p<.01). As with lack of planning, changes in sensation seeking were associated with heavy drinking during both the college and post-college years; however, these associations were significantly stronger during the college years. Further, sensation seeking was also associated with AUD during both timeframes.

Alcohol Behavior and Enhancement Expectancies.

Enhancement expectancies were strongly correlated with alcohol behavior intercepts (rs=.61–.71), changes across Waves 1-4 (rs=.45–.70), and changes across Waves 4-7 (rs=.45–.61). Models constraining correlated change estimates during Waves 1-4 and Waves 4-7 indicated that enhancement expectancy changes were more strongly associated with heavy drinking during the college years (r=.70), compared to the post-college years (r=.51) (χΔ [dfΔ=1]=33.44, p<.001). Unexpectedly, enhancement expectancy changes were more strongly associated with changes in AUD symptoms during the post-college years (r=.61), compared to the college years (r=.45) (χΔ [dfΔ=1]=11.73, p<.001). In summary, changes in alcohol enhancement expectancies and alcohol behavior moved in the same direction; steeper increases in enhancement expectancies were associated with steeper increases in alcohol behavior (e.g., during the college years), and steeper decreases in enhancement expectancies were associated with steeper decreases in alcohol behavior (e.g., during the post-college years).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between changes in alcohol use and problems and impulsivity risk factors (lack of planning, general sensation seeking, enhancement expectancies) from ages 18–35 in a cohort recruited during their freshmen year in college. Using an exploratory LGM approach, distinct developmental trajectories were identified during the primary college (ages 18–21) and post-college years (ages 21–35). Specifically, lack of planning and sensation seeking decreased rapidly during the college years, whereas alcohol behavior decreased rapidly in the post-college years (see supplement for estimated and observed means).

Confirmatory LGMs examined how changes in the facets of impulsivity are correlated with alcohol behavior during these developmental periods. The current study built on prior findings that linear changes in lack of planning and alcohol use are moderately correlated from ages 18–35 (Littlefield et al., 2010, Littlefield et al., 2009). Here, results suggested that the link between the rates of change in heavy drinking and lack of planning is particularly strong during the college years (rs=.63 vs. post-college years rs=.34). Notably, lack of planning was not associated with the rate of change in AUD symptoms. The rate of change in general sensation seeking was also correlated with heavy drinking, particularly during the college years (r=.61; post-college years r=.29) and AUD during both periods (college years r=.48; post-college years r=.46). Finally, alcohol enhancement expectancies were moderately to strongly correlated with the rates of change in alcohol use and AUD during both developmental periods (rs=.45–.70). We are unaware of prior studies that have examined how sensation seeking changes are correlated with alcohol behavior beyond emerging adulthood, or how alcohol expectancy changes are correlated with alcohol behavior during any developmental period. In summary, distinct developmental processes may underlie changes in alcohol use and problems across emerging and young adulthood. Further, risk factors may relate differently to alcohol use and problems across distinct periods of adulthood. Finally, these findings highlight the utility of an exploratory LGM approach, while also considering interpretability, to identify how alcohol use may change in relation to risk or protective factors.

Across analyses, a pattern emerged in which changes in most alcohol measures were correlated with changes in risk factors during the primary college years. For general measures of impulsivity (lack of planning, sensation seeking), associations with changes in heavy drinking were most pronounced during the college years. Notably, changes in enhancement expectancies were associated with all alcohol behaviors across both developmental periods. The shift of general impulsivity being less correlated with heavy drinking later in adulthood could be due to compulsivity becoming more important as behavioral patterns become automated. Prior work has shown that impulse control is more strongly related to cigarette smoking in emerging adulthood, rather than later in adulthood (Littlefield and Sher, 2012). It should be noted, however, that this pattern was not shown for AUD. Additionally, these findings suggest that sensation seeking and enhancement expectancies may be effective targets of AUD interventions during the college and post-college years. For example, evidence supports the use of behavioral economic interventions with college students, which may work by acknowledging the immediate reward obtained by drinking and highlighting how drinking impedes progress toward long-term goals (Murphy et al., 2012). A similar approach may help adults who are not in college (e.g., highlighting how drinking interferes with familial obligations or occupational goals).

The current findings can also inform etiological models of AUD by identifying the relevant risk factors and protective factors across developmental contexts. Emerging adulthood is a time of elevated risk-taking, and college is an environment with many social opportunities to drink (Slutske, 2005). In contrast, the post-college years are marked by occupational responsibilities (e.g., being at a workplace at expected times) and a greater number of personal obligations (e.g., parenting). These findings suggest that the rate of change in drinking within a collegiate environment may be most pronounced among individuals high in certain facets of impulsivity. It is possible that individuals, even those high in impulsivity, become less inclined to drink heavily later in life due to personal responsibilities. However, there is also evidence that impulsivity risk factors (disinhibition) affect role selection in the post-college years, such that individuals higher in impulsivity have fewer role transitions that would limit drinking (Lee et al., 2015). Alternatively, the current findings could be considered with regard to legal drinking. It is possible that impulsivity and sensation seeking are more strongly related to illegal, underage alcohol use than legal, of-age alcohol use (e.g., via risk taking or rule breaking). Therefore, the observed age-related shift in impulsivity risk factors may be driven by a number of factors including: 1) greater number of social drinking opportunities in the college environment, which may be particularly appealing to individuals high in impulsivity (Kahler et al., 2003); 2) the consequences of illegal, college-age drinking, which may be a barrier to individuals low in impulsivity (Henges and Marczinski, 2012); 3) personal obligations during the post-college years limiting heavy drinking, even among those high in impulsivity (Gotham et al., 2003); or 4) some combination of these environmental shifts. Therefore, the relationship between drinking, its risk factors, environment, and development is nuanced.

Finally, these findings are consistent with prior studies that have examined how sensation seeking and lack of planning change together over time, which have been a focus of the dual-systems literature. Whereas changes in general sensation seeking and lack of planning were correlated during the college years (r=.46), these changes were uncorrelated in the post-college years. In contrast, changes in lack of planning and enhancement expectancies were significantly correlated only after college (r=.24). For comparison, prior studies have found that quadratic, but not linear, changes in sensation seeking and impulse control correlated (Harden and Tucker-Drob, 2011).

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of the current study should be considered when interpreting and looking to build on these findings. First, 93% of participants were White, and studies of more diverse samples are needed. Second, participants were recruited as college freshmen, and college has a unique influence on increasing alcohol use and problems (Slutske, 2005). Third, the data-driven, exploratory change models identified in the current sample were applied to the same sample in confirmatory LGMs models, and this can result in overfitting to a specific sample. Consequently, the change models identified in the current study may provide a poor fit to other samples. A split-sample approach could allay these concerns by using separate samples for exploratory and confirmatory LGMs. However, this approach was not taken in the current study due to sample size. Thus, these analyses may be considered exploratory and require replication in independent samples. Fourth, other well-fitting, 2-factor LGMs could be further explored, with linear and either curvilinear or quadratic change factors (Tomarken and Waller, 2003). Prior studies of the current sample have implemented autoregressive models (Littlefield et al., 2012), which are mathematically equivalent in fit to LGMs (Wood and Jackson, 2013, Rovine and Molenaar, 2005). Similarly, when implementing exploratory analytic approaches, it is easy to arrive at model solutions that do not have practical application. Thus, it is important to consider interpretability. It is also worth noting that, although the models identified here fit the data well, there is substantial heterogeneity in change across the observed time frame. Mixture modeling approaches, for example, could examine the relevance of different risk factors and protective factors among those who experience the steepest increases/decreases in drinking in different developmental contexts. Finally, although the current analyses clarify when and which of these two facets of impulsivity are important, future studies could examine how the imbalance of reward seeking and lack of planning relates to alcohol problems during different developmental periods. Furthermore, future studies could test the acquired preparedness model to delineate the relationship among these risk factors, such as whether lack of planning affects subsequent changes in alcohol expectancies (McCarthy et al., 2001).

The measures of sensation seeking and impulse control should also be considered when evaluating studies of impulsivity or impulsivity-like constructs. Sensation seeking was assessed using four items, including questions of sensation seeking, broadly (e.g., “long for excitement”), as well as deviance (e.g., “urge to do harmful, shocking things”). Importantly, measurement coverage is a limitation here and in similar studies in the literature (e.g., the CNLSY uses respective three-item measures for sensation seeking and impulse control). Thus, more comprehensive measures are needed in future studies. Perhaps tempering concerns in the current study, all measures demonstrated adequate internal consistency, and correlations among sensation seeking and lack of planning were consistent with the impulsivity literature. Finally, the implications of general and domain-specific reward sensitivity measures should also be considered when interpreting these results. General sensation seeking may inadequately assess urges to engage in substance use, but enhancement expectancies may be a proxy for alcohol use and problems. It is unclear whether general or specific measures best represent sensation seeking or lack of planning.

Summary

This study highlights the importance of lack of planning, sensation seeking, and alcohol enhancement expectancies to the rates of change in adult alcohol use and AUD. Notably, all risk factors were related to the rate of change in heavy drinking from ages 18–21, and alcohol enhancement expectancies had large and significant associations with alcohol behavior changes well into young adulthood (age 35). Finally, this study demonstrated the value of examining developmental risk factors across distinct periods, informed by a data-driven analytic approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was support by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grants R01 AA13987, R37 AA07231, and KO5 AA017242 to Kenneth J. Sher and F31 AA022294 and K23 AA026635 to Jarrod M. Ellingson. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Conflict of interest declaration: none.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest declaration: none.

References

- American Psychiatric A (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed., American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd SJ, Corbin WR, Fromme K (2014) Parental and peer influences on alcohol use during the transition out of college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 28:960–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993) Alternative ways of assessing model fit, in Testing Structural Equation Models, Testing Structural Equation Models (BOLLEN KA, LONG JS eds), pp 136–162, Sage, Beverly Hills, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Mulaik SA (1993) Trait ratings from descriptions of behavior as mediated by components of meaning. Multivariate Behav Res 28:111–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA (2008) The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124:111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Levita L, Libby V, Pattwell S, Ruberry E, Soliman F, Somerville LH (2010) The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Developmental Psychobiology 52:225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews TM, Sher KJ (1992) Using adapted short MASTs for assessing parental alcoholism: Reliability and validity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 16:576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS (2006) Maturing Out of Alcohol Dependence: The Impact of Transitional Life Events. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 67:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboeck PR, Nicholson J, Kouros C, Little TD, Garber J (2015) Integrating developmental theory and methodology: Using derivatives to articulate change theories, models, and inferences. Applied Developmental Science 19:217–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI (2004) Effects of censoring on parameter estimates and power in genetic modeling. Twin Research and Human Genetics 7:659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson JM, Vergés A, Littlefield AK, Martin NG, Slutske WS (2013) Are bottom-up and top-down traits in dual-systems models of risky behavior genetically distinct? Behavior Genetics 43:480–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL (1978) Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1968) Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, Educational and Industrial Testing Services, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1975) Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, Educational and Industrial Testing Services, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N (2000) The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 109:122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham HJ, Sher KJ, Wood PK (2003) Alcohol involvement and developmental task completion during young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 64:32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009) Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology 60:549–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Ram N (2018) Latent growth and dynamic structural equation models. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 14:55–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Steele JS, Ram N, Nesselroade JR (2013) Exploratory latent growth models in the structural equation modeling framework. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 20:568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist MN, Wiley JF (2018) MplusAutomation: An R package for facilitating large-scale latent variable analyses in mplus. Structural Equation Modeling:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Tucker-Drob EM (2011) Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology 47:739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC (1943) The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. Revised Edition ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henges AL, Marczinski CA (2012) Impulsivity and alcohol consumption in young social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors 37:217–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ (2006) Comparison of longitudinal phenotypes based on number and timing of assessments: A systematic comparison of trajectory approaches II. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 20:373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Read JP, Wood MD, Palfai TP (2003) Social environmental selection as a mediator of gender, ethnic, and personality effects on college student drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 17:226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Littlefield AK, McCabe CJ, Mills KL, Flournoy J, Chassin L (2017) Longitudinal modeling in developmental neuroimaging research: Common challenges, and solutions from developmental psychology. Dev Cogn Neurosci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK (1994) Anxiety and drinking behavior: moderating effects of tension-reduction alcohol outcome expectancies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 18:852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Ellingson JM, Sher KJ (2015) Integrating social-contextual and intrapersonal mechanisms of “maturing out”: Joint influences of familial-role transitions and personality maturation on problem-drinking reductions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 39:1775–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ (2012) Smoking desistance and personality change in emerging and young adulthood. Nicotine Tob. Res. 14:338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Steinley D (2010) Developmental trajectories of impulsivity and their association with alcohol use and related outcomes during emerging and young adulthood I. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 34:1409–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK (2009) Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology 118:360–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Stevens AK, Ellingson JM, King KM, Jackson KM (2016) Changes in negative urgency, positive urgency, and sensation seeking across adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences 90:332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Stevens AK, Sher KJ (2014) Impulsivity and alcohol involvement: Multiple, distinct constructs and processes. Curr Addict Rep 1:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Vergés A, Wood PK, Sher KJ (2012) Transactional models between personality and alcohol involvement: A further examination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 121:778–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Miller TL, Smith GT, Smith JA (2001) Disinhibition and expectancy in risk for alcohol use: Comparing black and white college samples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 62:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Tisak J (1990) Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika 55:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP (2012) A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80:876–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998) Mplus User's Guide. 7th ed., Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SL, Molina BSG, Belendiuk KA, Donovan JE (2012) Racial differences in the development of impulsivity and sensation seeking from childhood into adolescence and their relation to alcohol use. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 36:1794–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Sher KJ, Slutske WS, Jackson KM (2005) Hangover frequency and risk for alcohol use disorders: Evidence from a longitudinal high-risk study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 114:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K (2011) The role of person-environment interactions in increased alcohol use in the transition to college. Addiction 106:1104–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Harden KP (2013) Differential changes in impulsivity and sensation seeking and the escalation of substance use from adolescence to early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology 25:223–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Administration USV, Veterans Administration Medical Center Regional Learning Resources S, Sciences USVACOMH, Behavioral, Health NIoM, Washington University Psychiatry D (1985) Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Version III-A, Veterans Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W (1995) Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV), St. Louis, MO. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, Goldring E (1989) National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III Revised (DIS-III-R), Washington University, St. Louis, MO. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Hennessy M (2007) A biosocial-affect model of adolescent sensation seeking: the role of affect evaluation and peer-group influence in adolescent drug use. Prev Sci 8:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovine MJ, Molenaar PCM (2005) Relating factor models for longitudinal data to quasi-simplex and NARMA models. Multivariate Behav Res 40:83–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ (1985) Subjective effects of alcohol: The influence of setting and individual differences in alcohol expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 46:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ (1999) Pathological alcohol involvement: A developmental disorder of young adulthood. Development and Psychopathology 11:933–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE (1991) Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100:427–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G (1996) Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: a latent variable cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 105:561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS (2005) Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM (2007) On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment 14:155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Wiers RW (2010) Implicit cognition and addiction: A tool for explaining paradoxical behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:551–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2010) A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology 52:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J (2008) Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology 44:1764–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW, Ames SL, Grenard JL, Sussman S, Stacy AW (2008) Interactions between implicit and explicit cognition and working memory capacity in the prediction of alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 94:116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG (2003) Potential problems with “well fitting” models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 112:578–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Stacy AW (2006) Implicit cognition and addiction. Current Directions in Psychological Science 15:292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Winick C (1962) Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin on Narcotics 14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK, Jackson KM (2013) Escaping the snare of chronological growth and launching a free curve alternative: General deviance as latent growth model. Development and Psychopathology 25:739–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK, Steinley D, Jackson KM (2015) Right-sizing statistical models for longitudinal data. Psychological Methods 20:470–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M (1994) Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.