Abstract

Background:

The left ventricular assist device (LVAD) has become a common medical option for patients with end-stage heart failure. Although patients’ chances of survival may increase with an LVAD compared to medical therapy, the LVAD poses many risks and requires major lifestyle changes, thus making it a complex medical decision. Our prior work found that a decision aid for LVADs significantly increased decision quality for both patients and caregivers and was successfully implemented at six LVAD programs.

Methods:

In follow up, we are conducting a nationwide dissemination and implementation project, with the goal of implementing the decision aid at as many of the 176 LVAD programs in the United States as possible. Guided by the Theory of Diffusion of Innovations, the project consists of four phases: 1) building a network; 2) promoting adoption; 3) supporting implementation; and 4) encouraging maintenance. Developing an LVAD network of contacts occurs by using a national baseline survey of LVAD clinicians, existing professional relationships, and an internet-based strategy. A suite of resources targeted to promote adoption and support implementation of the decision aid into standard LVAD education processes are provided to the network. Evaluation is guided by the RE-AIM framework, where clinician and patient surveys and qualitative interviews determine the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance achieved.

Conclusions:

This project is a true dissemination study in that it targets the entire population of LVAD programs in the US, and is unique in its use of social marketing principles to promote adoption and implementation. The implementation plan is intended to serve as a test case and model for dissemination and implementation of other evidence-based decision support aids and strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with progressive illness face an array of decisions about invasive and potentially life-prolonging technologies.1 For advanced heart failure patients, the left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is increasingly becoming one such decision.2–4 LVADs have become a mainstream treatment option for many people dying from heart failure.5,6 However, LVADs come with significant trade-offs. Survival benefits are balanced by many potential complications and a high degree of ongoing device care.7

Our team developed and tested a decision aid (DA) for patients and their families considering an LVAD. The Multicenter Trial of a Shared Decision Support Intervention for Patients and their Caregivers Offered Destination Therapy for End-Stage Heart Failure (DECIDE-LVAD trial) was a randomized stepped wedge, multi-center trial designed to test both the effectiveness and implementation of the DA among patients being evaluated for LVAD and their caregivers.8–10 Through longitudinal patient and caregiver surveys, the trial found that the DA was effective at improving patient and caregiver decision quality, with those receiving the DA demonstrating higher knowledge around LVAD and greater concordance between their values and treatment choice. LVAD implantation rates also decreased among patients receiving the DA intervention. Additionally in the intervention period, all six participating sites successfully adopted the DA and 95% of their enrolled patients received the DA as part of the standard evaluation process. After the trial, five of the sites maintained use of the DA as standard practice. Qualitative interviews examined implementation and found that clinicians were able to fit the DA into their existing clinical workflow and supported the use of the tool as standard education.8–10 Additionally, in another study examining use of the DA outside of the trial, clinicians reported a strong desire for unbiased tools and need for adequate patient education materials in the complex LVAD decision-making setting.11

Although often effective in controlled research,12 DAs are rarely implemented or disseminated outside of the research setting.13–16 Given the unique context of LVAD decision-making and proven effectiveness and implementation of our DA, we are now conducting a national dissemination and implementation project. The goal is to approach every LVAD program in the country about using our DA (n=176), with the a priori aim of at least 50% of programs implementing the DA into their standard patient education. This project is a true dissemination study in that it targets the entire population of LVAD programs in the United States. In the interest of informing dissemination projects in other settings, this manuscript describes the methods of a theory based national dissemination project guided by the Theory of Diffusion of Innovations and evaluated using the RE-AIM framework.

METHODS

Anonymized data and materials will be made available from the corresponding author upon request. The project is funded by a three-year implementation award from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (SDM-2017C2-8640), and received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Colorado. The project consists of four phases: 1) building a network; 2) promoting adoption; 3) supporting implementation; and 4) encouraging maintenance. To accomplish the aims, we first develop an LVAD network of contacts, then attempt adoption of the DA with each of those network contacts, and support implementation of the DA into their standard education and practice workflows.

An overview of project methods and evaluation strategies are in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Project Overview

Dissemination and Implementation Frameworks

Our primary dissemination strategy is guided by the Theory of Diffusion of Innovations (DOI).17 DOI explains how an innovative idea, behavior, or product spreads throughout a group of people, and argues that people generally can be categorized based on how quickly they adopt: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. See Table 1 for a description of these categories. We are focusing our initial adoption and implementation on the early adopter and early majority programs, as success by these groups can then be used to encourage adoption by the later majorities. The seven key constructs that influence adoption in DOI—cost, effectiveness, simplicity, comparative advantage, trialability, compatibility, and observability—guide targeted outreach and resource development to ensure adoption and foster implementation.

Table 1:

Definitions of Adopters from Theory of Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) and Project Status

| DOI Category | DOI Definition | Project-Specific Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Innovator | • Rush to the innovation • Willing to take risks • First to develop ideas • Little needs to be done to appeal to this group |

Programs from the original DECIDE-LVAD Trial who maintained use of DA after trial. |

| Early Adopter | • Often opinion leaders or people in leadership roles • Aware of the need to change and are comfortable adopting new ideas • Do not generally need information to convince to change |

Programs who express interest in DA prior to project start and adopt the DA early on in project. |

| Early Majority | • Not often leaders but do adopt new ideas before the average person • Need to see evidence that the innovation works • Strategies include success stories and evidence of effectiveness |

Programs approached by study team and adopt early-to-midway through project. |

| Late Majority | • Skeptical of change, and generally only adopt an innovation after it has been tried by the majority • Strategies include evidence of successful adoption at other sites |

Programs that adopt the DA late in the project, after several attempts by the study team. |

| Laggards | • Most difficult group • Strategies include fear appeals and outside pressure including policy |

Programs that never become adopters and are targeted for the policy brief. |

| Project Status Category | Project-Specific Definition | |

| Adopter | Programs that express interest in the DA and receive 50 free packets of the pamphlet and video. | |

| Refuser | Programs that expressly refuse the 50 free packets of DAs. | |

| Implementer | Adopter program that reports using the DA in clinical practice. | |

| Failed Adopter | Adopter program that reports never using or stopped use of the DA in clinical practice. | |

DA, decision aid; DOI, Diffusion of Innovation.

We also utilize the RE-AIM framework for evaluation.18,19 Developed by Dr. Russell Glasgow and colleagues, the RE-AIM framework assesses an intervention, guideline or policy’s potential for dissemination and public health impact using five criteria: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance. RE-AIM has been used to translate research into practice and to help programs implement in “real-world” settings.18,20 Recent research from our team on RE-AIM includes expanding its focus on implementation, adaptations and costs,21 pragmatic use of the model,22 and integration of quantitative and qualitative approaches.23,24 This project’s intervention and implementation strategies focus on achieving adoption, implementation and maintenance, while our evaluation measures the entire RE-AIM criteria.

DECIDE-LVAD Decision Aid

As described above as part of the DECIDE-LVAD Trial, we developed a two-pronged intervention consisting of a patient/caregiver-directed DA and a clinician-directed decision training. Following the Ottawa Decision Support Framework and International Patient Decision Aid Standards,25–27 and utilizing results from an extensive needs assessment28–30 and a user-centered design approach,31 we developed an 8-page pamphlet and 26-minute video DA (currently available at patientdecisionaid.org).32 In the trial, the clinician decision training occurred at a site visit at time of intervention implementation and consisted of a grand rounds-style presentation and a 90-minute coaching session on clinician communication for staff directly involved in LVAD patient education and care.33

Settings

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) maintains a list of accredited LVAD programs published on their website.34 This CMS-approved program webpage is the only compiled list of active LVAD programs available, and as of April 2020, there are 176 programs. This list forms the denominator of total programs of our outreach efforts. The project team periodically monitors this list to determine if programs are added or removed.

Each LVAD program has a multidisciplinary team, as mandated by CMS.35 This team typically consists of advanced heart failure cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, palliative care specialists, and social workers. Additionally, most programs have advanced practice providers and LVAD coordinators (typically registered nurses) as part of the team. CMS also mandates that a patient “be fully informed prior to making the final decision on treatment”.35 At most programs, the LVAD coordinators conduct the patient education, sometimes with the assistance of other specialists like social workers and palliative care specialists.

Phase 1: Building a Network

The first step in implementing the DA at all 176 LVAD programs in the US is to build a network of contacts at those programs. Thus, a key first task is to find a contact at each of the programs who is willing to work with us to support adoption and implementation of the DA at their site. To obtain contacts, we use four strategies: 1) prior professional relationships; 2) nationwide survey distributed through professional societies and a mechanical circulatory support coordinator listserv; 3) in-person recruitment at professional society conferences, on-site presentations, and institutional meetings; and 4) an internet-based search strategy. A list of all available contacts at every program is maintained in a master spreadsheet. This spreadsheet includes all 176 programs, and the name, role and email address for every contact garnered, with descriptions and date stamps of any communication that has occurred.

Prior professional relationships:

The core project team includes an advanced heart failure cardiologist and nurse practitioner and a geriatrician and shared decision-making expert with professional contacts in the advanced heart failure community across the country. Close contacts are approached at the start of the project and those expressing interest in our DA are designated “early adopters” with whom we are piloting adoption and implementation strategies. The “innovator” group is comprised of the original sites from the DECIDE-LVAD trial who are still using the DA as standard education. Later in Phase 1, the core team approaches professional relationships that are less well established, as well as asking close contacts (site-investigators from the DECIDE-LVAD trial, members of our stakeholder panel, and early adopter programs) to help identify relationships and contacts they may have at remaining programs. The core team has established memberships and connections within multiple organizations, including the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant, and the American Association of Heart Failure Nurses, all of which are leveraged for finding program contacts in Phase 1.

Nationwide baseline survey:

We are conducting an Internet-based survey to assess how likely a program is to adopt an LVAD DA. Through an iterative process, our team developed a survey with questions on shared decision making, as well as questions covering the seven key constructs of adoption as identified by DOI.12 The most important goal of the survey is to identify contacts and determine a program’s likelihood of adoption. Thus, the key questions include: (1) ”Do you routinely use decision aids for patients considering LVADs” and listing which one(s), (2) “How likely would your program be to adopt an LVAD decision aid in the next six months?”, and (3) a place for the respondent to report for which LVAD program they work and their name and email address where we can share DA information. The survey is included as a supplement.

The sampling frame for this survey is members of the advanced heart failure team, including advanced heart failure cardiologists and advanced practice providers, cardiothoracic surgeons, LVAD coordinators, and transplant social workers. As such, we utilize four lists maintained by the following professional societies and groups:

American College of Cardiology – Heart Failure Section

American Association of Heart Failure Nurses

Society for Transplant Social Workers

A listserv for Mechanical Circulatory Support coordinators

The survey is built in Qualtrics and its link sent over an email blast through each society twice.

In-person recruitment:

The core team attends several professional society meetings annually to either present project data or promote the DA at an exhibitor booth, where the DA details can be shared and contact information gathered. The core team also visits other institutions for meetings and presentations, which can lead to in-person communication about the DA dissemination and subsequent follow-up over email. Later in the process, programs that we have not yet contacted may be targeted for in-person discussion and one-on-one meetings.

An internet-based search strategy:

Any remaining program without an identified contact are researched using internet searches and discussions with stakeholders to identify names and email addresses of team members leading or involved with the LVAD program at that site. If no contact is found, a final strategy is to call the program’s general cardiology number and ask to speak with a member of the team.

Phase 2: Promoting Adoption

Once we have identified a contact at a program, we will reach out regarding their interest in using the DA with their patients. To facilitate early use, we offer 50 free packets of our DA, including professionally printed pamphlets and DVD copies of the video. Those who respond with interest in the DAs are sent the packets and considered an “adopter”; subsequent packets of DAs are sent to programs that express interest in receiving more. See Table 1 for definitions of program status.

After conducting outreach to our “innovator” and “early adopter” programs, we then email contacts garnered by the other means. For those individuals who respond to the Baseline Survey and provide their name, email address, and program name, we categorize them based on their responses to the questions of whether they are currently using a DA and how likely they would be to use one, based on DOI categories. Programs are contacted in phases:

Those who report that they already use our DA.

Those who report they would be “very likely” or “likely” to use a DA.

Those who report they are using a DA other than ours.

And lastly, those who report they are “unlikely” or “very unlikely” to use a DA.

We focus our adoption strategies on those who are more likely to adopt use of the DA, who become the “early majority”, then move on to those who may take more time or convincing to buy-in, the “late majority”. If there are multiple respondents from the same program, we contact each individually.

Emails to contacts are sent up to 3 times. If we receive no response, we attempt to find another contact at that program and do the emailing process again. If a program expressly states in a response email that they do not want the DA, they are considered a “refuser”. Status of each contacted program is reported in the master spreadsheet, and programs are grouped based on when they adopted. See Table 1 for a description of program labels for this project.

Adoption materials:

We have developed resources to encourage adoption, which are provided to all programs at time of DA delivery. This includes copies of two user guides: a one-page guide that conveys the main benefits and utilizations of the DA (touching on the key constructs of DOI), to be shared with program team members to help obtain buy-in; and a 4-page “getting started” guide that provides best practices and lessons learned for implementing the DA into standard practice. Approximately six weeks after the DAs are shipped, we send a follow-up email to help encourage adoption. The email asks the program contact if they received the package, opened it, and have any comments on using them yet, and then directs them to our online resources and encourages them to reach out to us with any questions or concerns.

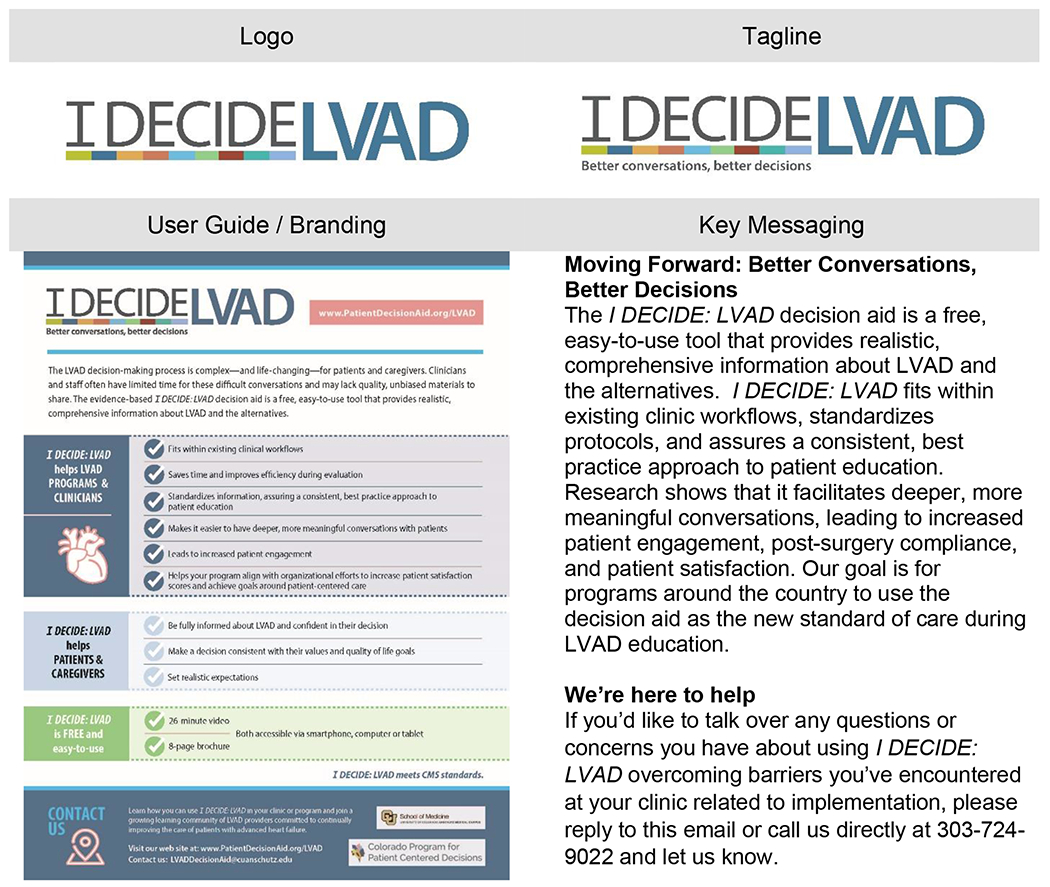

Brand identity and key messaging:

Utilizing social marketing principles, we are following a strategy to highlight the benefits of using the DA, mitigate the costs, promote tangible resources, and clearly explain how best to implement – in order to facilitate wide adoption. Promotion of the DA’s use follows a marketing framework often seen in commercial/industry work. An essential aspect of this is developing a recognizable brand identity, as well as key and consistent messaging in all outreach materials.36 This aspect of the project has been designed in collaboration with a professional communication firm. Utilizing interviews and meetings with stakeholders, and iterative development with the core team, the communication firm developed a brand name, logo, tag line, brand graphics, and key messages. The branding logo and key messaging are in Figure 2. Key messaging is included in the initial adoption email sent to programs, subsequent email communications, newsletters, user guides, social media and website. This branding and messaging strategy aims to draw attention, ensure professionalism, and overall encourage adoption. These factors become increasingly important as we attempt to garner adoption from those “late majority” programs.17,36

Figure 2:

Branding and Messaging

Phase 3: Supporting Implementation

Once a program becomes an adopter (receives hardcopies of DA), we shift our focus to supporting and encouraging implementation of the DA into their standard process for patient education during LVAD evaluation. To do this, we provide several resources and regular communication to keep the DA on the forefront of clinicians’ minds and help with any concerns or questions they may have while trying to implement. Given the large scope of this endeavor, we designed a virtual strategy based on principles of Minimum Intervention Needed for Change.37 This is a stepped care approach that initially uses the least complex and least costly approaches that can reasonably be expected to be effective. These resources attempt to tackle some of the challenges learned from the DECIDE-LVAD trial and address the key constructs of DOI. See Table 2 for a summary of strategies.

Table 2:

Implementation Strategies

| Strategy | Definition |

|---|---|

| Webinar training | • Online one-hour course to support clinicians in leading shared decision making conversations around LVAD • Includes lessons learned from the DECIDE-LVAD trial, communication tools to improve patient-provider conversations, and frequently asked questions • Accredited to provide credit for continuing medical education and maintenance of certification for clinicians |

| Troubleshooting calls | • Invite to schedule a call with our team to discuss questions, concerns or issues with implementation • Calls occur with at least two members of core team, and can be done one-on-one or in a group setting • Meant to provide any resource or support that is needed to programs starting out or struggling with implementation |

| Invitation to meet at a conference | • Invite clinicians to meet in person with any of the core team during the cardiology annual meetings • Help facilitate the ongoing adoption and implementation |

| Newsletters | • Quarterly email newsletter sent to the network • Provides updates, resources, and testimonials from programs who have used the DA • Meant to keep communication regular, remind of the resources available, and encourage ongoing implementation |

| • Project Twitter account (@idecide_lvad) • Helps to keep communication regular, advertise resources and updates, and make connections with both adopter and non-adopter clinicians to build the network • Daily tweets, re-tweets, likes, and follows • Following advanced heart failure and LVAD-focused organizations – such as the American College of Cardiology and International Society for Heart and Lung Transplant – cardiology departments within medical institutions, and advanced heart failure clinicians |

|

| Patientdecisionaid.org website | • Website houses the DAs and links to all of the above resources for free and easy access |

| Follow-up emails | • Follow-up emails to those adopters who later report that they are not using the DAs • Offer support and suggest scheduling a troubleshooting call • Regular follow-up emails are sent to check in and provide additional guidance and encouragement |

DA, decision aid; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Phase 4: Encouraging Maintenance

A key focus of this project is to design a process that encourages ongoing maintenance and sustainability of the use of the DA. To make the DA easy to access, we provide a PDF version of the pamphlet and streaming of the video on our website, patientdecisionaid.org, both free to use. Additionally, we provide the 50 free copies of the professionally produced DAs to programs for the duration of the project. At the project’s completion, they will be available to purchase on our website, sold at cost. Our website will also continue to house links to all adoption and implementation resources for free and easy access.

Additionally, we continually nurture the LVAD network of adopters for shared learning by continuing our points of communication (newsletters, Twitter, calls as needed) and expanding those communications as interest dictates. As mentioned above, the existing relationship with cardiology organizations and professional societies help us to continue to network and promote sustainment. Already, our DA is linked on the American College of Cardiology’s CardioSmart and the Society of Transplant Social Worker websites.

Lastly, to promote long-term maintenance and continued late implementation, we encourage “outer context”38 – changes in policies related to LVAD shared decision making. Specifically, we are working with our stakeholders and policy advisors to develop a policy brief and information strategy to encourage CMS to mandate shared decision making as part of their coverage policy. While this may not impact policy changes in the timeframe of this project, this step is important to assure future DA use among non-adopters and sustainment among adopters.

Measuring Outcomes

To assess outcomes, we are using a comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation based on RE-AIM. Key RE-AIM terms and dimensions are operationalized (and underlined) in this section and in Table 3. RE-AIM guided the development of the Baseline Survey, Check-In Survey, Final Survey, Patient Survey, and interview guide.

Table 3:

RE-AIM Outcomes

| Measure | Description | Data Type | Timeframe | RE-AIM Outcome Dimension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | Eff. | Adopt. | Impl. | Maint. | ||||

| Baseline Survey | Determine readiness to adopt | Quantitative | First 6 months | X | X | |||

| Spreadsheet | Adoption communication and tracking of programs | Quantitative | Throughout project period | X | ||||

| Check-In Survey | Assess implementation and number of patients who received DA | Quantitative | Every 4-6 months post-adoption | X | X | |||

| Communications | Trouble shooting calls and one-on-one emails | Qualitative | Throughout project period | X | X | |||

| Interviews | Examine in-depth the adoption, implementation and maintenance with a sub-set of programs | Qualitative | Twice per program throughout years 2 and 3 | X | X | X | ||

| Final Survey | Assess reach, implementation and maintenance | Quantitative | Last 6 months | X | X | X | ||

| Patient Survey | Assess effectiveness of DA | Quantitative | Last 6 months | X | ||||

DA, decision aid; RE-AIM, Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

The Baseline Survey, as described above, is sent out prior to distribution of the DA to assess how likely a program would be to Adopt. The Check-In Survey is sent to clinicians from programs in the LVAD network of adopters to assess if the DA is being used and to what extent; it is sent every 4-6 months to capture Implementation and Reach over time. The Final Survey is a longer questionnaire for adopter programs that asks more detailed questions on Implementation and Maintenance of the DA and various implementation strategies, and is administered in the final months of the project. A Patient Survey is sent to patients from a sub-set of programs who successfully implement the DA in order to assess Effectiveness of the tool. Finally, qualitative interviews with a sub-set of the organizations are used to capture in-depth understanding of Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance, with the interview guide focusing on how the DOI key constructs affect DA use. Interviews are conducted among a sub-set of programs twice during the project period.

Reach:

Reach is defined as the proportion and representativeness of eligible patients who receive the DA. In this project, we do not have the precise denominator of eligible patients at each site (the most challenging aspect of measuring Reach) to measure this directly. Indirectly, Reach is measured using the Check-In Survey, where programs report how many patients were evaluated for LVAD over the past 4-6 months, and of those, what percentage received the DA.

Effectiveness:

Effectiveness was the primary outcome assessed in the earlier DECIDE-LVAD trial, which demonstrated patient-level effectiveness in terms of improvements in decision quality. We are not replicating the costly and burdensome patient data collection in this project. Based on literature, we know that if DAs (including our own) are implemented, they will produce desired shared decision-making outcomes.12 However, we are utilizing this network to assess among a broader set of programs in order to better understand the generalizable effectiveness. Thus, a sub-set of programs that successfully implement the DA are sending the Patient Survey to about 20 of their patients. The Patient Survey asks questions regarding LVAD knowledge and values-choice concordance (decision quality), as well as acceptability of the DA and how it was used in their encounter.

Adoption:

Adoption refers to the number and representativeness of programs who used the DA out of the total number of programs in the country, and reasons for these results. We are utilizing the CMS list of 176 certified LVAD programs, available on the CMS website, as our denominator. Programs that express interest in the DA and receive the 50 free copies from us are considered Adopters. This is assessed by tracking which programs are contacted, respond, and are sent packets. The Baseline Survey is used to assess predictors of Adoption, specifically sections on attitudes toward shared decision-making, DOI key constructs, and likelihood of adoption.

Implementation:

Implementation metrics include consistency or fidelity of delivery, adaptations made to the intervention and Implementation strategies, and the costs of program delivery. Among sites who become Adopters, we assess Implementation of the DA and incorporation into standard education at their program. Every 4-6 months, the main contact at each adopter program is sent the Check-In Survey to report if their program is (1) currently using the DA, (2) used but stopped, or (3) is not currently using the DA. Among those who are using, we ask to what extent (once, a few times, frequently, or always [as standard of care]). For those not using, we ask their intention to use in the future and barriers to DA use.

In years 2 and 3 of the project, we look in-depth at Implementation through qualitative interviews with a sub-set of programs. We purposely sample from groupings of programs by (1) region of the United States, (2) university-affiliated versus non-university-affiliated, and (3) whether respondents reported in the Baseline Survey if the program was likely or unlikely to adopt a DA. Based on these groupings, we randomly select 20 programs for interviews, with some purposeful sampling in order to ensure we interview programs that are adopters and non-adopters, successful and unsuccessful implementers. We aim to interview one LVAD coordinator and one doctor from each program, in order to explore consistency of delivery of the DA (over staff, sites, and time), challenges to implementation, and adaptations made. Using the DOI key constructs, we also investigate which constructs are the most important considerations when implementing a new tool such as the DA.

Maintenance:

Maintenance in RE-AIM has referents at both the individual and setting/staff levels.23 In this project, we are focusing on the setting-LVAD site level. Among Adopting and Implementing sites, we assess plans for continued use at the end of the study through the qualitative interviews and Final Survey, and determine the percentage and representativeness of sites that are planning to continue the program as initially implemented, not using our DA or strategies, or are continuing but modifying or adapting their use. At the end of the project, the Final Survey and qualitative interviews help further assess program’s attitudes towards shared decision making after adopting the DA, facilitators and barriers to implementation, and extent of DA use.

Analysis

Quantitative:

We first conduct descriptive data analysis on the Baseline Survey to allow us to initiate Phases 1 and 2. The survey is used to map respondent programs into levels of readiness to adopt the DA. To describe the overall sample, we use means and standard deviations, we also use organizational characteristics to explore predictors of adoption using logistic regression. While the primary purpose of this project is national level adoption, one embedded scientific question is to explore how well the questions on attitudes and the DOI constructs predict likelihood of adoption, subsequent adoption, and meaningful implementation.

To assess implementation, we perform analyses on the routine follow-up surveys to assess ongoing implementation and quantity of DAs delivered, again using descriptive data and analyses of variance and covariance to assess characteristics of sites with different levels of implementation and maintenance, as well as multi-level regression to identify setting and individual level factors associated with reach and effectiveness outcomes. We also track the uptake of our social media campaigns and the use of our website.

Qualitative:

All interviews are recorded and professionally transcribed. Analyses of qualitative data are planned as a continuous process beginning with initial interviews and continuing throughout and beyond the data generation period. Analysis of the transcripts begin with multiple team members repeated readings to achieve immersion, followed by coding using an emergent rather than a priori approach, in order to emphasize interviewee perspectives and de-emphasize team member assumptions. The synthesis stage of data analysis involves triangulating the findings from all of the coded transcripts, as well as program demographics, to explore comparisons across LVAD programs. The trustworthiness of study findings are heightened through attention to the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the data. The qualitative software package ATLAS.ti v 7.0 is used to manage and analyze the data.

Measures of Success/Primary Endpoints

Primary endpoints are degree of adoption and degree of implementation. The following a priori measures of success have been defined and agreed upon between the project team and the funding agency: Year 1: We aim to have the 20 early adopter programs adopted, and at least 75 patients reached; Year 2: We aim to have an additional 50 programs adopted and 775 patients reached; Year 3: we aim to have had contact with and attempted adoption with the remaining programs and 1775 patient reached. Of the 176 programs contacted, we expect at least 100 to implement them into their standard education process by the end of the project period.

DISCUSSION

Advanced heart failure continues to progress in the United States and LVAD technology is constantly evolving. From prior work, we know there is a strong desire for balanced, unbiased, easy-to-use materials to support patients during this complex decision-making process.10,28–30 However, we also know from the DECIDE-LVAD trial that there are still reservations as well as implementation challenges that raise concerns about adoption amongst programs.8,10 Thus, successful dissemination and sustainment of a DA not only requires ongoing review and updating of the tools as new technologies are developed, but also requires supporting programs with resources to overcome potential programmatic concerns, evolving barriers, and changing context.39,40 We anticipate these different perspectives in the programs during this project, and hope to learn more about the needs of LVAD teams in order to further tailor tools for implementation and maintenance.

Strengths of our approach include being a true dissemination study targeting the entire population of LVAD centers in the US, and the use of implementation science models for both planning (DOI) and evaluating (RE-AIM) the program. A primary research limitation is the lack of experimental comparisons of alternative dissemination strategies. The unique policy environment that encourages use of DAs, the national network of LVAD centers, and the investigators relationships with leaders of these centers are both strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, these unique features could limit generalizability of results. Yet, building a national network of advanced heart failure programs using the same DA might also facilitate in-depth learning about strategies for implementation and maintenance, including information on how to support caregivers and how to help families prepare for care at the end of life. These lessons might have wider applicability for decision support tools in other domains.

Finally, in addition to encouraging the adoption of our DA, this project can also serve as a foundation upon which other research teams can build when conducting dissemination and implementation of other evidence-based strategies. An atypical aspect of this work has been the reliance on social marketing principles, and utilizing tactics often seen in commercial/industry work.36 We lean heavily on these marketing tenets, perhaps more than we lean on our previous academic work. Successful use of social marketing in the medical decision-making and dissemination setting may be informative to other researchers who want to disseminate their own materials. Although integration of DAs into routine medical practice has typically been challenging,13–16 this project evaluates and makes available resources on how to successfully implement and maintain use of shared decision-making resources and strategies within the advanced heart failure world and can help to guide other broader efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Sources of Funding: Research reported in this publication is funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (SDM-2017C2-8640). The views, statements, opinions in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Dr. Glasgow’s time is also partially supported by NCI grant (P50CA244688).

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- DA

decision aid

- DECIDE-LVAD

The Multicenter Trial of a Shared Decision Support Intervention for Patients and their Caregivers Offered Destination Therapy for End-Stage Heart Failure

- DOI

Diffusion of Innovations

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- RE-AIM

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Baseline Survey

References

- 1.Goldman DP, Shang B, Bhattacharya J, Garber AM, Hurd M, Joyce GF, Lakdawalla DN, Panis CP, Shekelle PG. Consequences of health trends and medical innovation for the future elderly. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:W5R5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Francso S, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 129:e28–e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirklin JK, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, Myers SL, Miller MA, Baldwin JT, Young J, Naftel DC. Eighth annual INTERMACS report: Special focus on framing the impact of adverse events. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:1080–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb SB, Kucheryavaya AY, Khush K, Levvey BJ, Lund LH, Meiser B, Rossano JW, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fourth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2017; Focus Theme: Allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grady KL, Meyer PM, Dressler D, Mattea A, Chillcott S, Loo A, White-Williams C, Todd B, Ormaza S, Kaan A, et al. Longitudinal change in quality of life and impact on survival after left ventricular assist device implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larry A, McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, Dunlay SM, LaRue SJ, Lewis EF, Patel CB, Blue L, Fairclough DL, Leister EC, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention supporting shared decision making for destination therapy left ventricular assist device: the DECIDE-LVAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIlvennan CK, Matlock DD, Thompson JS, Dunlay SM, Blue L, LaRue SJ, Lewis EF, Patel CB, Fairclough DL, Leister EC, et al. Caregivers of patients considering a destination therapy left ventricular assist device and a shared decision-making intervention: the DECIDE-LVAD trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:904–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matlock DD, McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, Morris MA, Venechuk G, Dunlay SM, LaRue SJ, Lewis EF, Patel CB, Blue L, et al. Decision Aid Implementation among Left Ventricular Assist Device Programs Participating in the DECIDE-LVAD Stepped-Wedge Trial. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Morris MA, McIlvennan CK, Allen LA. Organic dissemination and real-world implementation of patient decision aids for left ventricular assist device. MDM Policy Pract. 2018;3:2381468318767658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards AG, Clay C, Legare F, van der Weijden T, Lewis CL, Wexler RM, Frosh DL. “Many miles to go ...”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR, Sodano AG, King JS. Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:716–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legare F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers E Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harden SM, Strayer TE III, Smith ML, Gaglio B, Ory MG, Rabin B, Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. National Working Group on the RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Goals, Resources, and Future Directions. Front Public Health. 2020;7:390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton RC, Chambers DC, Glasgow RE. An Extension of RE-AIM to Optimize Sustainment: Addressing Dynamic Context and Promoting Health Equity over Time. Front Public Health. 2020;8:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes W, Ritzwoller D, Glasgow RE. Stakeholder perspectives on costs and resource expenditures: addressing economic issues most relevant to patients, providers and clinics. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasgow RE, Estabrooks PA. Pragmatic applications of RE-AIM for health care initiates in community and clinical settings. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2018;15:E02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtrop JS, Glasgow RE, Rabin B. Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods. BMJ. 2018;18:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Ottawa Decision Support Framework. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html. Published June 22, 2015. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 26.Fowler FJ Jr., Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, Thomson R, Barratt A, Barry M, Bernstein S, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIlvennan CK, Allen LA, Nowels C, Brieke A, Cleveland JC, Matlock DD. Decision making for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices: “there was no choice” versus “I thought about it an awful lot”. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIlvennan CK, Matlock DD, Narayan MP, Nowels C, Thompson JS, Cannon A, Bradley WJ, Allen LA. Perspectives from mechanical circulatory support coordinators on the pre-implantation decision process for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices. Heart Lung. 2015;44:219–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McIlvennan CK, Jones J, Allen LA, Lindenfeld J, Swetz KM, Nowels C, Matlock DD. Decision-making for destination therapy left ventricular assist devices: implications for caregivers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katsulis Z, Ergai A, Leung WY, Schenkel L, Rai A, Adelman J, Benneyan J, Bates DW, Dykes PC. Iterative user centered design for development of a patient-centered fall prevention toolkit. Appl Ergon. 2016;56:117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson JS, Matlock DD, McIlvennan CK, Jenkins AR, Allen LA. Development of a Decision Aid for Patients With Advanced Heart Failure Considering a Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Device. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Cleveland JC Jr., Dunlay SM, LaRue SJ, Lewis EF, Patel CB, Walsh MN, Allen LA. A Multicenter Trial of a Shared Decision Support Intervention for Patients and Their Caregivers Offered Destination Therapy for Advanced Heart Failure: DECIDE-LVAD: Rationale, Design, and Pilot Data. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:E8–E20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. VAD Destination Therapy Facilities. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/MedicareApprovedFacilitie/VAD-Destination-Therapy-Facilities. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- 35.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Ventricular Assist Devices for Bridge-to-Transplant and Destination Therapy. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=268. Published October 30, 2013. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 36.Lee NR, Kotler P. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasgow RE, Fisher L, Strycker LA, Hessler D, Toobert DJ, King DK, Jacobs T. Minimal intervention needed for change: definition, use, and value for improving health and health research. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damschroder L, Hall C, Gillon L, Reardon C, Kelley C, Sparks J, Lowery J. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): progress to date, tools and resources, and plans for the future. Implement Sci. 2015;10:A12. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Hurlburt MS, Palinkas LA, Gunderson L, Willging CE, Chaffin MJ. Collaboration negotiation, and coalescence for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:915–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.